16TH CENTURY

The 16th century is the era of great expeditions and marks the beginning of the modern. In 1492, Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) crossed the Atlantic Ocean towards America under the Castilian flag. This new ocean route produced a wave of general curiosity. Artists and researchers like John White (active 1577-1593) took part in those expeditions and upon their return home, brought back watercolour sketches which showed the people and landscape of unknown lands. In order to better place the newly discovered species in scenes, the sovereigns at the time decided to create botanical gardens and erect menageries, which would would quickly become symbols of their power. The oldest botanical garden was erected in Pisa in 1544 by Cosimo I. de’ Medici (1519-1574). Bestiaries and herbariums decorated his wedding. With the help of the watercolour technique, artists like Giuseppe Arcimboldo (c. 1527-1593) in Italy, Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues (c. 1533-1588) in France and also Joris Hoefnagel (1542-c. 1600) in Flanders celebrated nature and especially the beauty of flowers, which were praised because of their symbolic character.

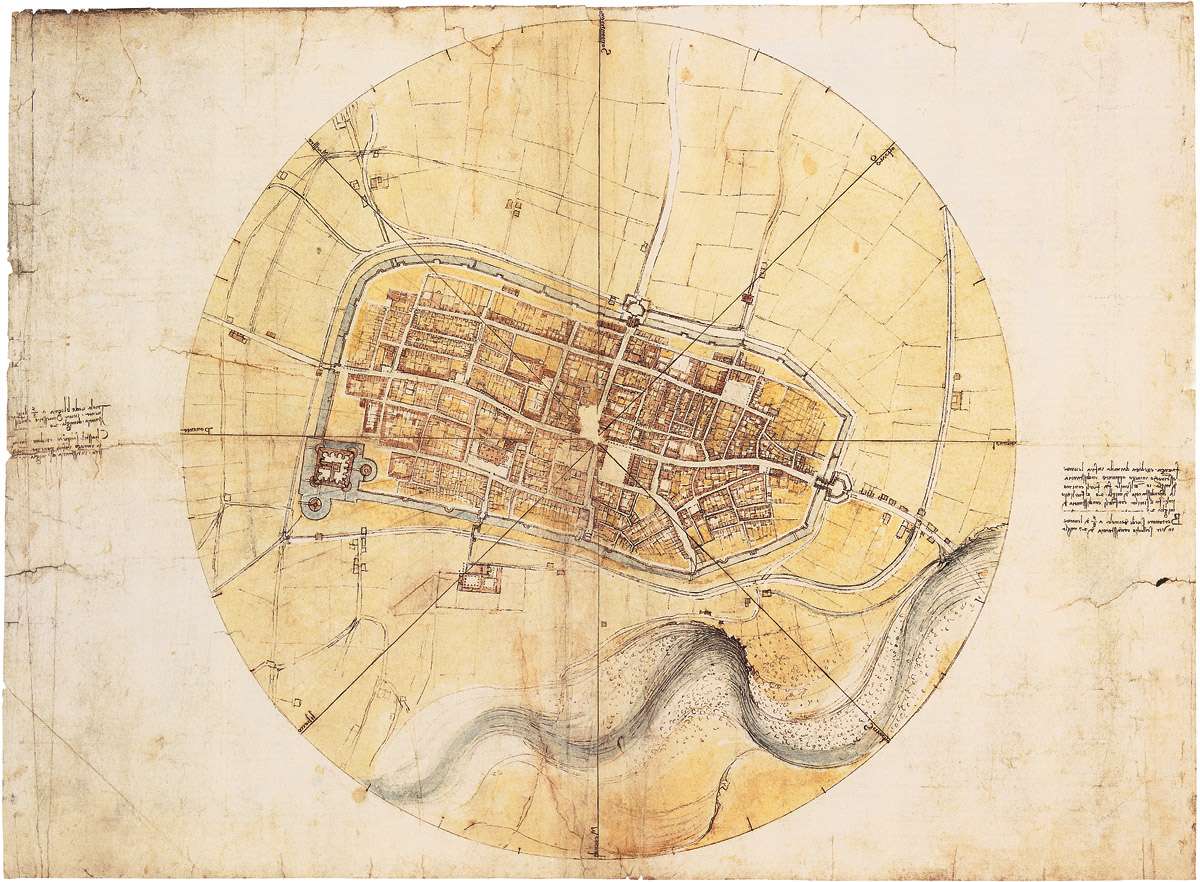

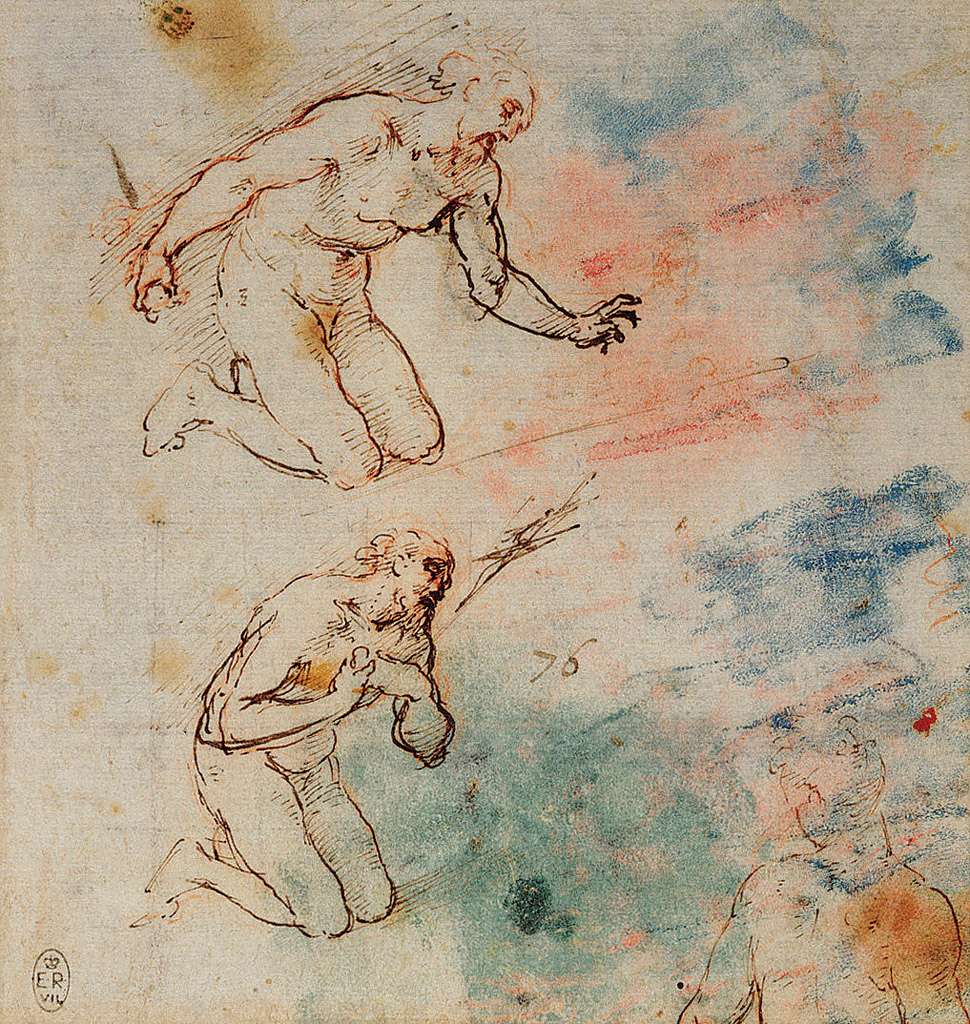

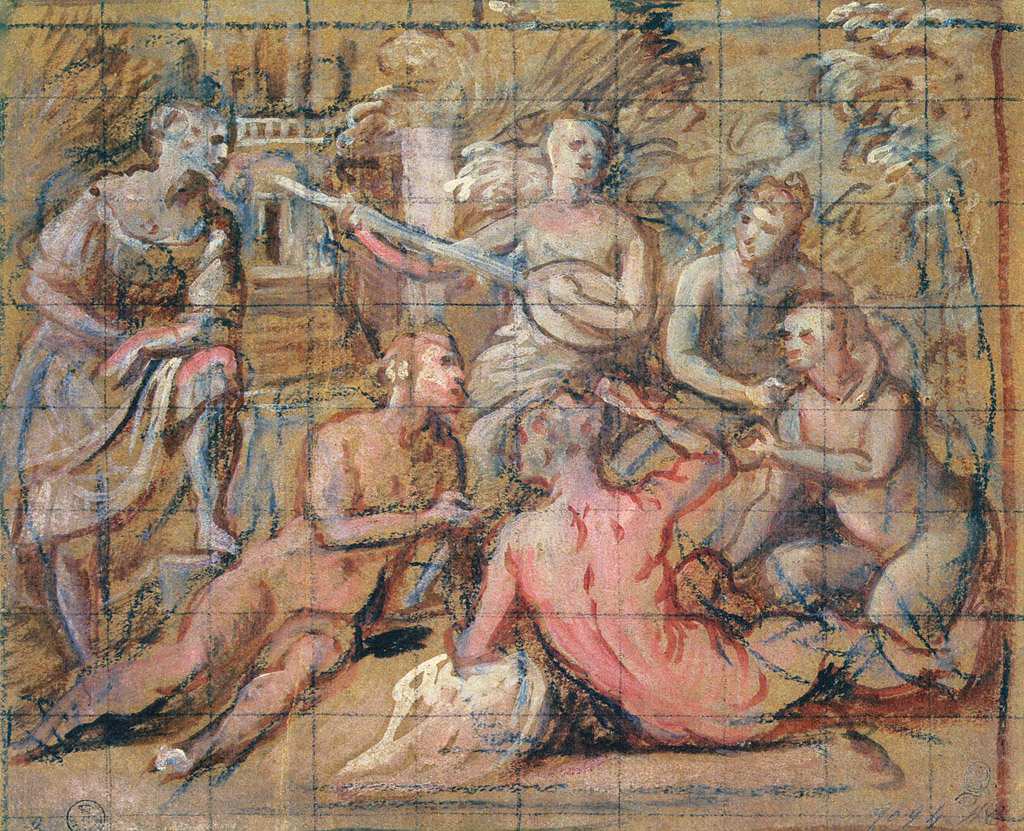

The 16th century represented the heyday of Italian art. The influential familes invested much in art in order to beautify the cities and to express their wealth. After Florence, the main artistic centers of Italy were Rome and Venice. In this phase of cultural and intellectual renewal, the social standing of artists transformed. They were no longer viewed as just hand workers but as scholars, Leonardo da Vinci, a veritable scientist, is the most striking example of this. He dissected, he was active in cartography (ill. 50 and ill. 52), and he busied himself with the aid of watercolour sketch with drapery (ill. 57 and ill. 80) as well as astmospheric effect. (ill. 79). While Roman art evolved a complete mastery of drawing, the Venetian art indulged in colour. Thus, landscapes and light effects became the true subjects of the works. Antonio da Correggio (c. 1489-1534) shared the divine nature of in his study The Glory of the Lord (ill. 88) through subtle modulations of light and darkness. This was possible through watercolour washing technique, which yielded a result which had a misty, graceful appearance and drew close to the concept of a heavenly perspective and the sfumato of Leonardo.

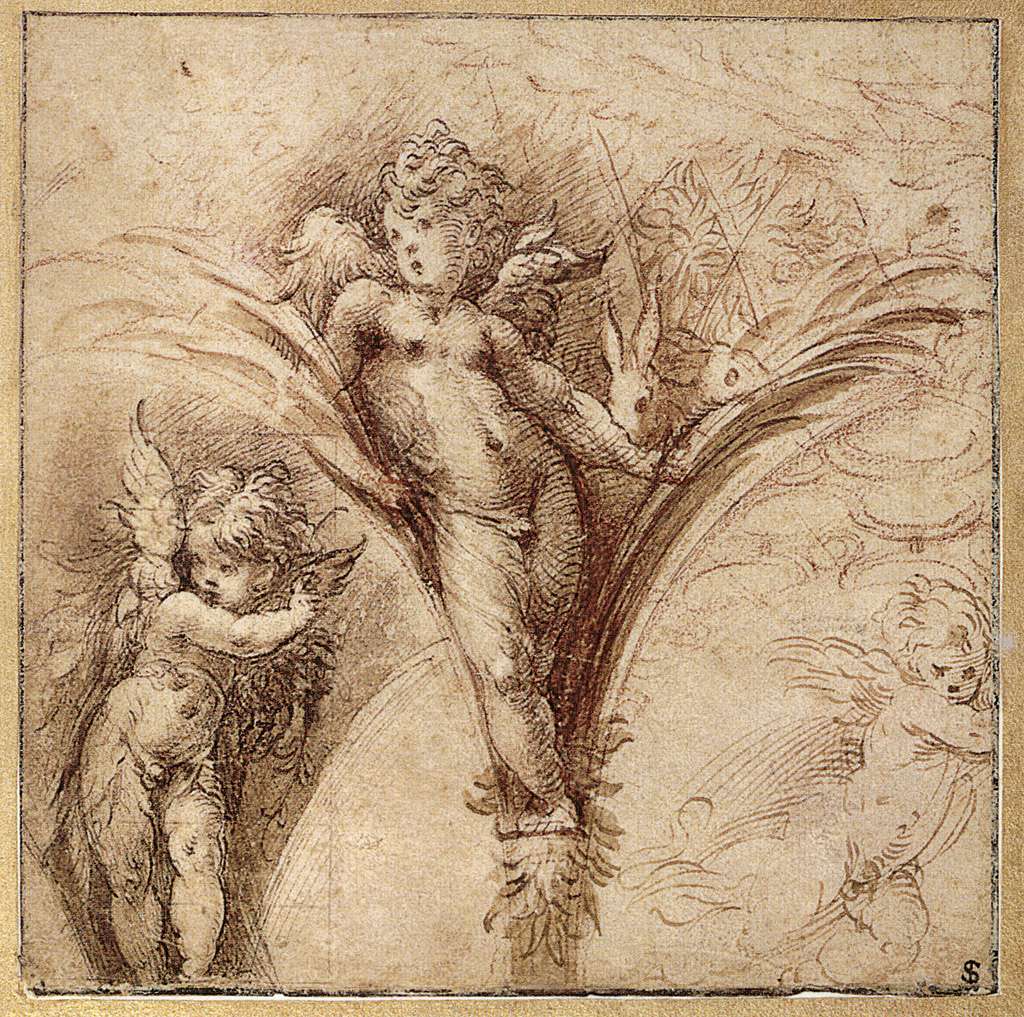

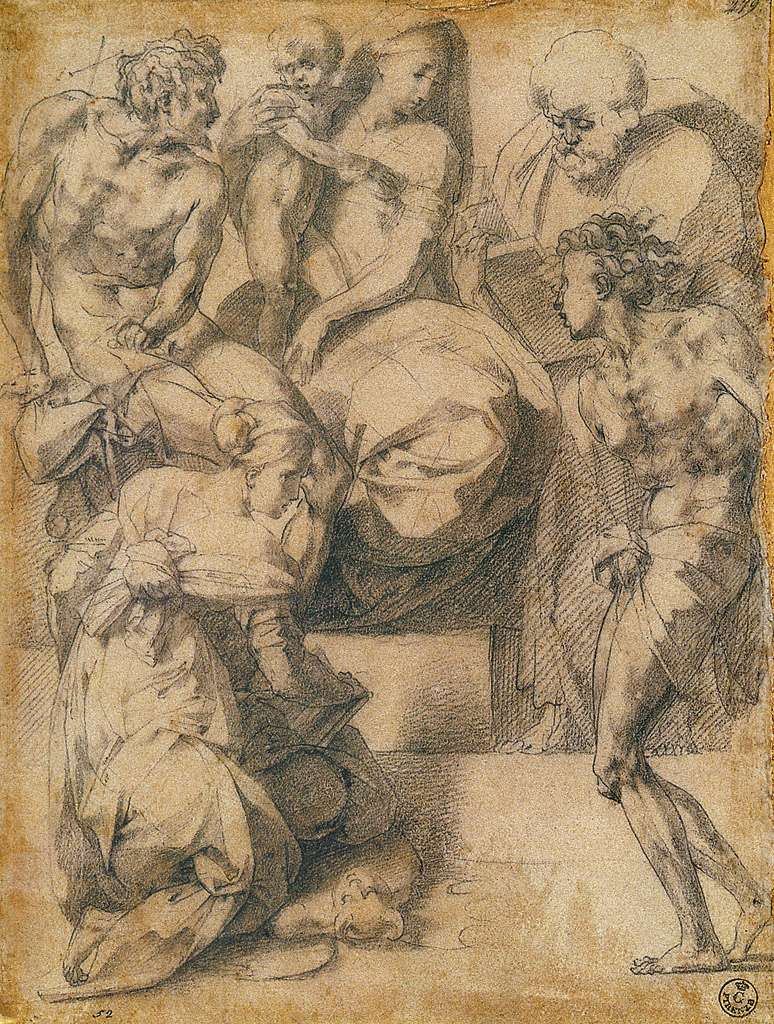

Italian art was also influenced by the plundering of Rome, which took place in 1527. The artists reacted to this political change and all of the perfect works of that time and acted contrary to tradition: They strove to produce surprising effects. This was presented in an execessive form, a deformation of proportions and a use of garish colours – this style was known under the name of Mannerism. Aforementioned distortions show themselves quite clearly in the manipulation of shadows – helped with watercolour technique – in the sketches for decorations from Rosso Fiorentino (1494-1540), Parmigionino (1503-1540), or Nicolò dell’Abate (1509/1512-1571).

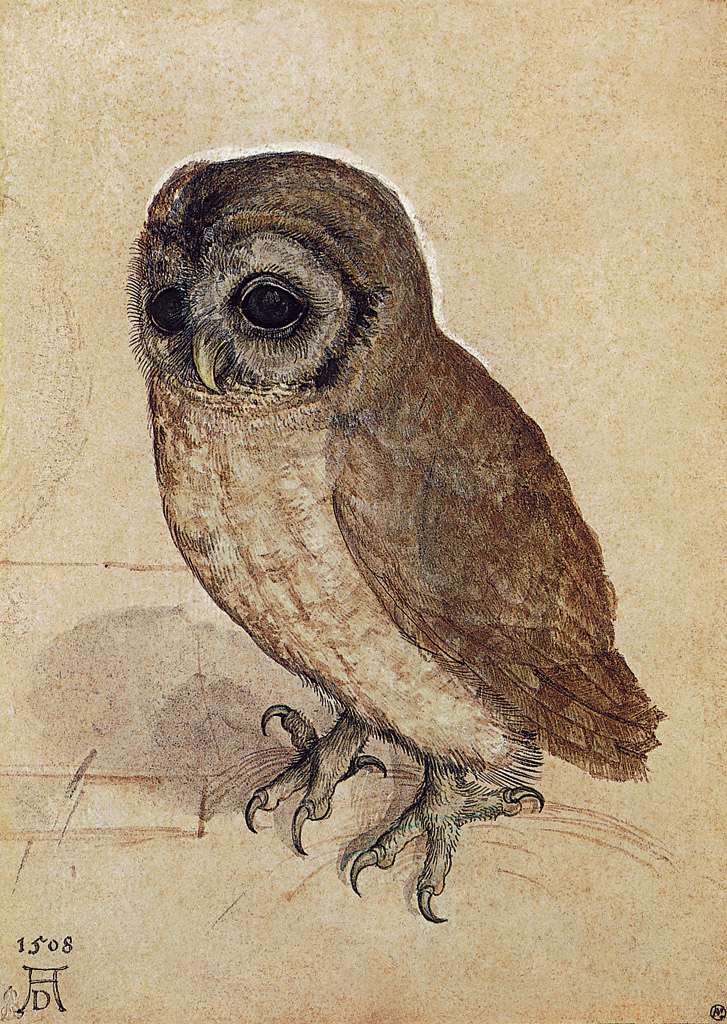

The artists of the north admired the Italian work. Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) was preoccupied with the idea of the Renaissance. On his trip to Italy, he fell in love with the landscape of the land and subsequently devoted himself unconditionally to watercolours (ill. 39). He carved himself out an independent status within his works and developed them further by studying light conditions and natural forms. Within the works of watercolourists, Dürer can be distinguished by three genres: landscape, scientific study, and sketches in the manner of early Italian Renaissance. Further efforts of the lanscape painters with recourse to watercolour technique can be found in Hanns Lautensack (c. 1520-1564/1565) who painted Imaginary Landscape (ill. 106) or Joris Hoefnagel, who in Windsor Castle, Seen from the North with Two Figures in the Foreground completely realistically portrayed the buildings of a fictitious land. Watercolour created for itself such a place in the landscape painting genre which it hereafter should not only defend but expand.

The Reformation brought about a crisis in the art of the north: With the proclaimed iconoclasm and the strict rejection of all luxury, even the patronage of the art underwent some drastic changes. In Italy, the Church was still the most important of the art patrons, while in the north, wealthy individuals especially functioned as sponsors, which gave them authority over the edited thematic materials of the artists. This could no longer be allowed: depending entirely on commissions from grand officials for religious subjects like they had done, without hesitation, before the Reformation. Consequently, artists like Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) devoted themselves to portraits with great success, whereby they gave watercolour technique preference.

The miniature portraits created with watercolour made it necessary for the colour to be finely rubbed in and for the background to be produced with gouache in order to allow the faces – whose colour tones and nuances could excellently be reproduced by the transparency of watercolour – to stand out. In England, the miniature painter Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619) dominated this art so perfectly that Queen Elizabeth I. (1533-1603) made him her official portraitist (ill. 110, ill. 111 and ill. 136). The advantages of the medium were gradually recognised.

43. After Andrea Mantegna, 1431-1506, Italian. Study of Drapery and Figures, c. 1500. Brush, ink, and black stone with grey wash and white highlights, 25 x 18.8 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Early Renaissance.

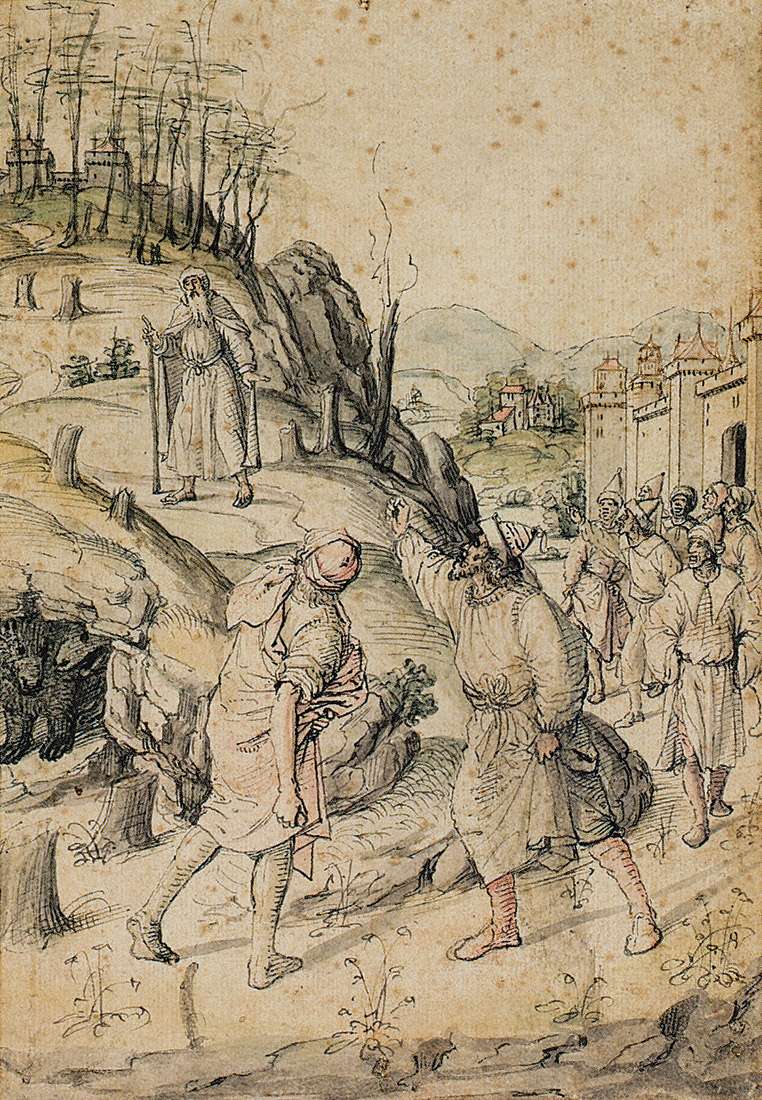

44. Jean Poyer, active 1483-1503, French. The Mocking of Elisha, c. 1500. Quill, black and brown ink, grey, pink, green, blue, and yellow wash, 21 x 14.5 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. Early Renaissance.

45. Bartolomeo Montagna, c. 1450-1523, Italian. A Study for Christ Enthroned, c. 1500-1520. Watercolour and white bodycolour, over black chalk, on blue paper, 31.6 x 22.2 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

46. After Andrea Mantegna, 1431-1506, Italian. A Roman Soldier Seated on his Shield, and Other Studies, c. 1500. Brush and ink, heightened with white, and pen and ink, 25 x 18.8 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Early Renaissance.

ANDREA MANTEGNA

(ISOLA DI CARTURO, 1430/1431 – MANTUA, 1506)

Mantegna: humanist, geometrist, and archaeologist of great scholastic and imaginative intelligence, dominated the whole of northern Italy by virtue of his imperious personality. Aiming at optical illusion, he mastered perspective. He trained in painting at the Padua School that Donatello and Paolo Uccello had previously attended. Even at a young age, commissions for Andrea’s work flooded in, for example the frescos of the Ovetari Chapel of Padua.

In a short space of time, Mantegna found his niche as a Modernist due to his highly original ideas and the use of perspective in his works.

His marriage with Nicolosia Bellini, the sister of Giovanni, paved the way for his entrée into Venice.

Mantegna reached an artistic maturity with his Pala di San Zeno (San Zeno Alterpiece). He remained in Mantova and became the artist for one of the most prestigious courts in Italy – the Court of Gonzaga. Classical art was born. Despite his links with Bellini and Leonardo da Vinci, Mantegna refused to adopt their innovative use of colour or leave behind his own technique of engraving.

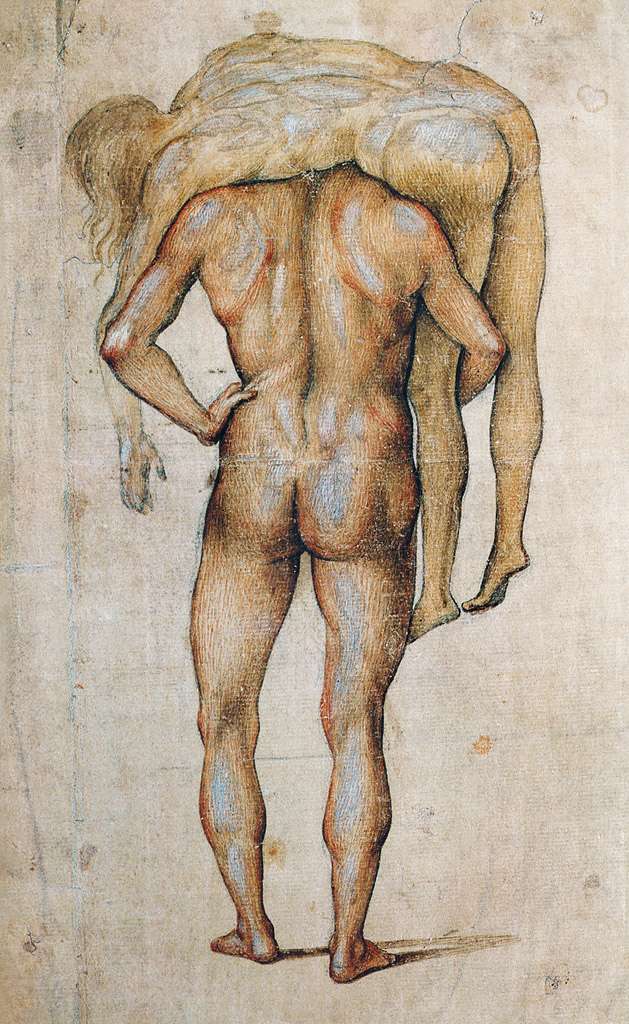

47. Luca Signorelli, c. 1440-1523, Italian. Nude Man Seen from Behind Carrying a Corpse on His Shoulders, c. 1500. Black chalk, brown wash, and watercolour on paper, 35.5 x 22.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Early Renaissance.

48. Andrea del Sarto (Andrea d’Agnolo), 1486-1530, Italian. Woman with a Book in Her Hand, date unknown. Red pencil and red watercolour on watermarked white paper, 24.2 x 20.1 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. High Renaissance.

49. Marco Basaiti, c. 1470-1530, Italian. Landscape with a Rocky Coast, c. 1507-1512. Watercolour, 20.3 x 27.4 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Early Rennaissance.

50. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519, Italian. A Map of Imola, 1502. Pen and ink, with coloured washes and stylised lines over black chalk, 44 x 60.2 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

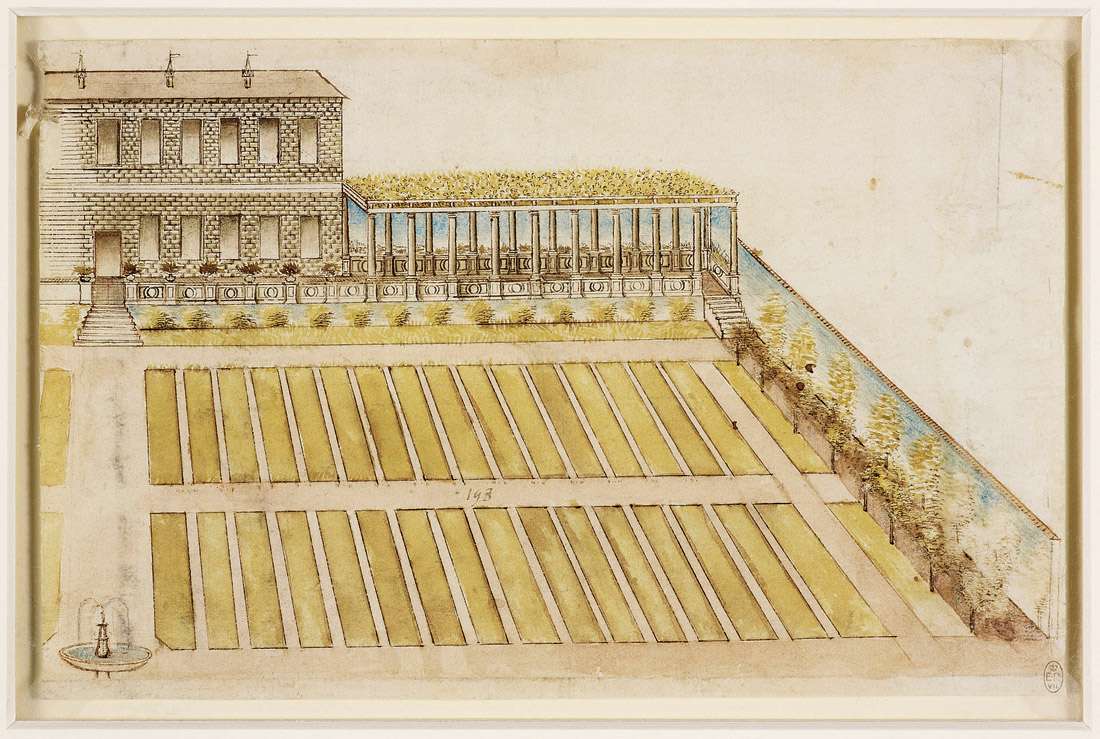

51. Anonymous, Italian. The Façade of a Rustic Town with a Colonnade and a Walled Garden, date unknown. Pen and ink, red chalk and watercolour, 17.4 x 27 cm. The Royal Collection, London.

52. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519, Italian. A Bird’s-Eye Map of Western Tuscany, c. 1503-1504. Pen and ink, wash, and blue bodycolour, over black chalk, 27.5 x 40.1 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

53. Albrecht Dürer, 1471-1528, German. Wing of a Hooded Crow, c. 1512. Watercolour and gouache on parchment, 19.6 x 20 cm. Grafische Sammlung, Albertina, Vienna. Northern Renaissance.

54. Albrecht Dürer, 1471-1528, German. A Young Hare, 1502. Watercolour and gouache on paper, 25 x 22.5 cm. Grafische Sammlung, Albertina, Vienna. Northern Renaissance.

55. Albrecht Dürer, 1471-1528, German. Barn Owl (Syrnium aluco), 1508. Watercolor on brown colored paper, accented by white gouache, brush and brown pen, gray and black ink, 19.2 x 14 cm. Grafische Sammlung, Albertina, Vienna. Northern Renaissance.

56. Albrecht Dürer, 1471-1528, German. Head of a Stag, c. 1503. Watercolour, 22.7 x 16 cm. Musée Bonnat, Bayonne. Northern Renaissance.

57. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519, Italian. The Arm of the Virgin, c. 1508-1510. Black and red chalks, pen and ink, brush, ink, and white heightening on pale red prepared paper, 8.6 x 17 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

58. Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola), 1503-1540, Italian. Three Studies of Putti, c. 1520. Pen, brown ink and brown watercolour over red chalk, 15.7 x 15.6 cm. The Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Mannerism.

59. Hans Süss von Kulmbach, c. 1480-1522, German. Saint Eustace and Saint George, c. 1511. Pen and brown ink, brush and grey wash, 21.3 x 18.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

60. Rosso Fiorentino, 1494-1540, Italian. Virgin and Child with Saints, c. 1522. Black pencil and grey watercolour on brownish-white paper, 33.1 x 25.3 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Mannerism.

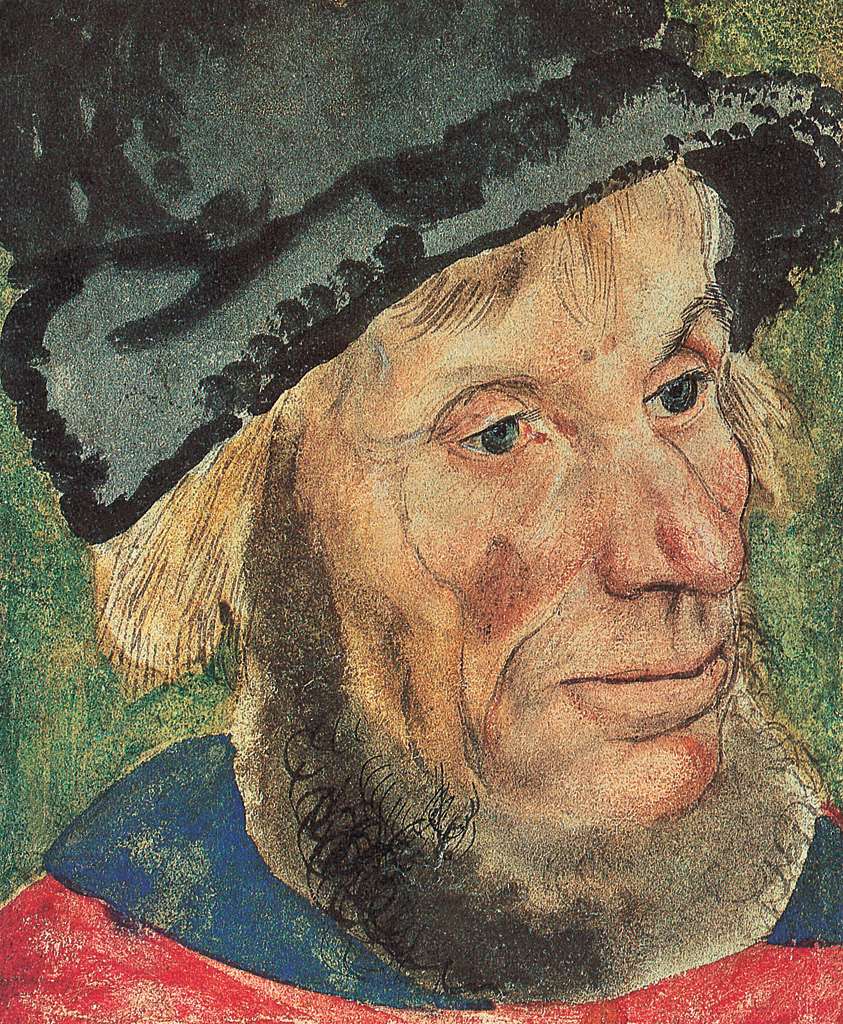

61. Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1472-1553, German. Head of Man with a Fur Hat, c. 1505-1506. Watercolour, 19.3 x 15.7 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel. Northern Renaissance.

LUCAS CRANACH THE ELDER

(KRONACH, 1472 – WEIMAR, 1553)

Cranach was one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance, as shown by the diversity of his artistic interests as well as his awareness of the social and political events of his time. He developed a number of painting techniques which were afterwards used by several generations of artists. His somewhat mannered style and splendid palette are easily recognised in numerous portraits of monarchs, cardinals, courtiers and their ladies, religious reformers, humanists, and philosophers. He also painted altarpieces, mythological scenes and allegories, and he is well-known for his hunting scenes. As a gifted draughtsman, he produced numerous engravings on both religious and secular subjects, and as a court painter, he was involved in tournaments and masked balls. As a result, he completed a great number of costume designs, armorials, furniture, and parade ground arms. The high point of the German Renaissance is reflected in his achievements.

62. Anonymous, Dutch. The Healing of the Blind Man, c. 1510-1520. Watercolour on glass, diameter: 24.1 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

63. Attributed to Biagio Pupini, active 1511-1551, Italian. The Judgment of Solomon, after Raphael, date unknown. Charcoal, brush, and grey wash, highlighted with white on blue paper, 23.8 x 31.9 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Renaissance.

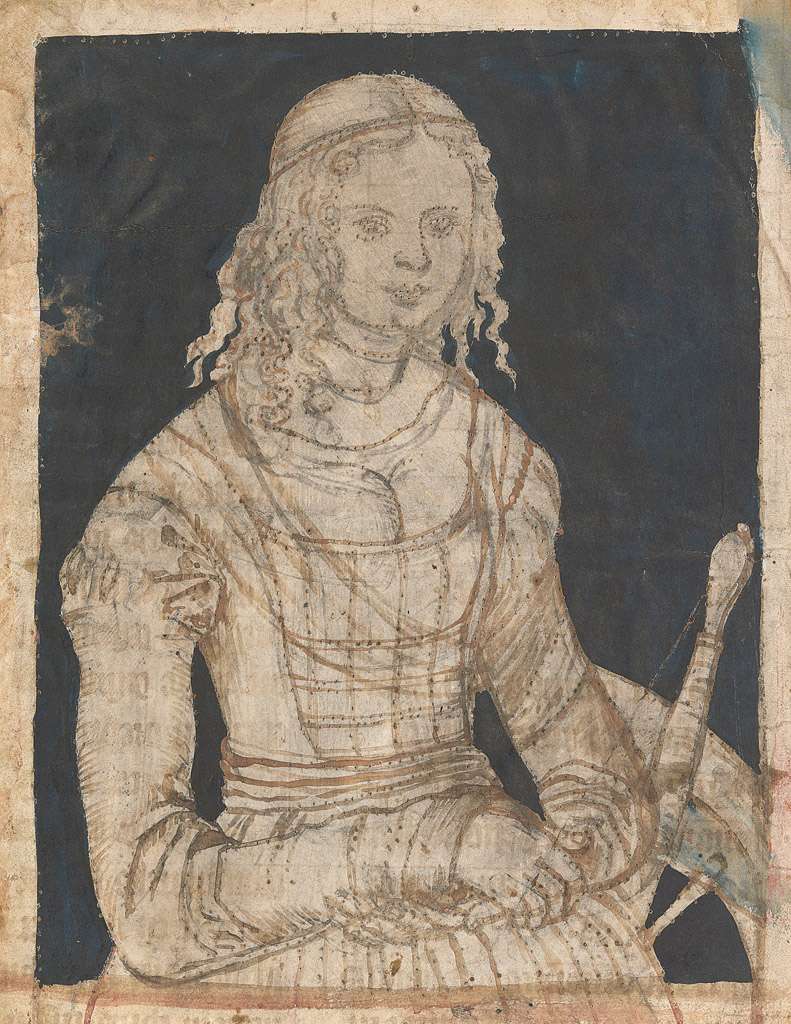

64. Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1472-1553, German. Saint Catherine, date unknown. Silverpoint, brush, brown ink, and indigo wash on vellum, pricked for transfer along brush lines, 16.7 x 12.8 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

65. Cesare da Sesto, 1477-1523, Italian. St Jerome, c. 1510-1515. Pen and ink, 14 x 13.2 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

66. Anonymous, German. Masquerade, c. 1515. Pen and brown ink with watercolour on laid paper, 23.3 x 23.7 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

67. Anonymous, German. Masquerade, c. 1515. Pen and brown ink with watercolor on laid paper, 23.3 x 23.7 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

68. Anonymous, German. Masquerade, c. 1515. Pen and brown ink with watercolour on laid paper, 23.3 x 23.7 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

69. Anonymous, German. Masquerade, c. 1515. Pen and brown ink with watercolour on laid paper, 23 x 23 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

70. Anonymous, German. Masquerade, c. 1515. Pen and brown ink with watercolour on laid paper, 23.4 x 23.7 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

71. Anonymous, German. Masquerade, c.1515. Pen and brown ink with watercolour on laid paper, 23.2 x 23.2 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

72. Anonymous, German. Masquerade, c. 1515. Pen and brown ink with watercolour on laid paper, 23.2 x 23.9 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

73. Anonymous, German. Masquerade, c. 1515. Pen and brown ink with watercolour on laid paper, 23.3 x 23.3 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

74. Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), 1483-1520, Italian. The Miraculous Draft of Fishes, c. 1515-1516. Gouache over charcoal on many sheets of paper, mounted on canvas, 31.9 x 39.9 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

RAPHAEL

(RAFFAELLO SANZIO)

(URBINO, 1483 – ROME, 1520)

Raphael was the artist who most closely resembled Phidias. The Greeks said that the latter invented nothing; rather, he carried every kind of art invented by his predecessors to such a pitch of perfection that he achieved pure and perfect harmony. Those words, ‘pure and perfect harmony’ express, in fact better than any others, what Raphael brought to Italian art.

From Perugino, he gathered all the delicate grace and gentility of the Umbrian School, he acquired strength and certainty in Florence, and he created a new style based on the fusion of Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s lessons under the light of his own noble spirit. His compositions on the traditional theme of the ‘Madonna and Child’ seemed intensely novel to his contemporaries, but for us it is difficult to fully understand, and it is now their time-honoured glory that maintains the vision of its originality and keeps its fame in tact after hundreds of years. He has an even more magnificent claim in the composition and realisation of those frescos with which, from 1509, he adorned the Stanze and the Loggia at the Vatican. The sublime, which Michelangelo attained by his ardour and passion, Raphael attained by the sovereign balance of intelligence and sensibility. One of his masterpieces, The School of Athens, was an autonomous world created by genius, thanks to the multiple details: The portrait heads, the suppleness of gesture, the ease of composition, and the life circulating everywhere within the light are his most admirable and identifiable traits.

75. Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), 1483-1520, Italian. The Death of Ananias, c. 1515-1516. Bodycolour on paper, mounted on canvas, 34.2 x 53.2 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

76. Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), 1483-1520, Italian. The Sacrifice at Lystra, c. 1515-1516. Gouache on paper, mounted on canvas, 34.7 x 54.2 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

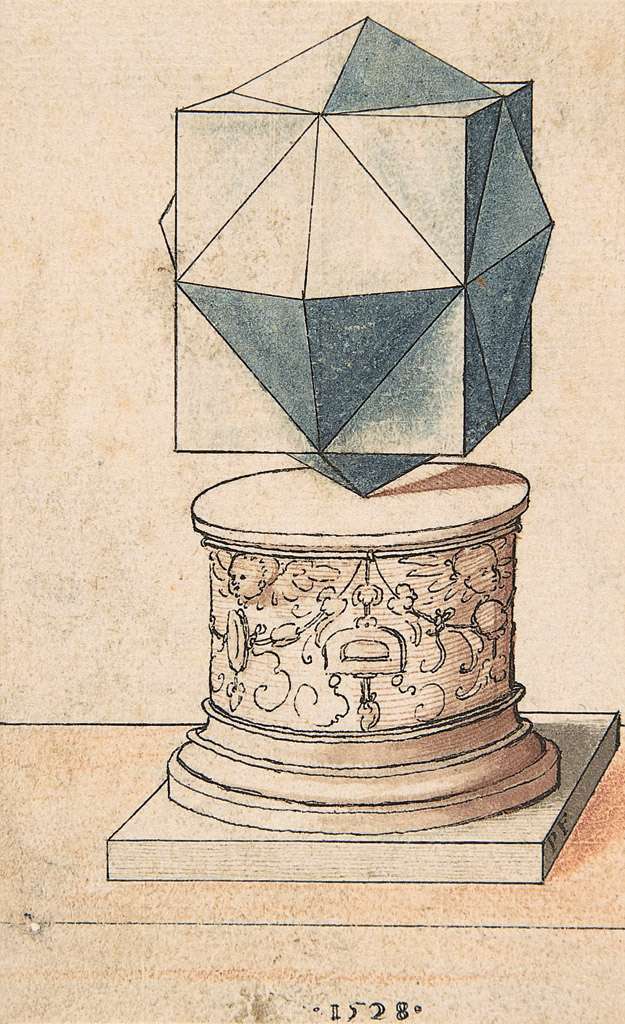

77. Peter Flötner, 1485-1546, German. Perspective Drawing of a Column Base with Geometrical Form, 1528. Pen and black ink, brush, bluish grey, and brown washes, 10.6 x 6.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

78. Attributed to Giovanni di Niccolo Mansueti, active 1485-1527. Three Mamluk Dignitaries, c. 1526. Brush and brown ink on light brown (discoloured?) paper, 30.4 x 17.8 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

79. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519, Italian. Storm Clouds over a Flooded Landscape, c. 1517-1518. Pen, ink, and brown wash over black chalk, 15.6 x 20.3 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

80. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519, Italian. The Drapery of the Virgin’s Thigh, c. 1515-1517. Charcoal and black chalk washed over in places, with touches of brown wash, and white heightening, 16.4 x 14.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

LEONARDO DA VINCI

(VINCI, 1452 – LE CLOS-LUCÉ, 1519)

Leonardo’s early life was spent in Florence, his maturity in Milan, and the last three years of his life in France. Leonardo’s teacher was Verrocchio. As a painter, he was representative of the scientific school of draughtsmanship, but he was more famous as a sculptor, being the creator of the Colleoni statue at Venice. He was well-grounded in the sciences and mathematics of the day as well as a gifted musician. His skill in draughtsmanship was extraordinary, shown by his numerous drawings as well as by his comparatively few paintings. His skill of hand was at the service of the most minute observation and analytical research into the character and structure of form. Leonardo was the first to date of the great men who had the desire to create in a picture a kind of mystic unity brought by the fusion of matter and spirit. Now that the ‘primitives’ had concluded their experiments, ceaselessly pursued during two centuries, by the conquest of the methods of painting, he was able to pronounce the words which served as a password to all later artists worthy of the name, painting is spiritual – cosa mentale. He completed Florentine draughtsmanship by applying a sharp subtlety to modelling by light and shade, which his predecessors had used only to give greater precision to their contours. This marvellous draughtsmanship, this modelling and chiaroscuro he used not only to paint the exterior appearance of the body but also, as no one before him had done, to cast over it a reflection of the mystery of the inner life. In the Mona Lisa and his other masterpieces he even used landscape not merely as a more or less picturesque decoration, but as a sort of echo of that interior life and an element of a perfect harmony.

81. Bernaert van Orley, 1488-1541, Flemish. Johan IV van Nassau and His Wife Maria van Loon-Heinsberg, c. 1528-1530. Pen and brown ink, watercolour over touches of black chalk, 34.9 x 49.1 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Northern Renaissance.

82. Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497-1543, German. Man in Armour, c. 1517-1519. Pen and watercolour, 40.6 x 29.5 cm. British Museum, London. Northern Renaissance.

HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER

(AUGSBURG, 1497 – LONDON, 1543)

The genius of Holbein blossomed early. His native city of Augsburg was then at the zenith of its greatness; on the high road between Italy and the North, it was the richest commercial city in Germany and the frequent resting place of the Emperor Maximilian. His father, Hans Holbein the Elder, was himself a painter of great merit, and he took his son into his studio giving him his entrance into the world of art. In 1515, when he was eighteen years old, he moved to the city of Basel, which at the time was considered the centre of learning, and it boasted that every house in it contained at least one learned man.

He set out for London with a letter of introduction to the King’s Chancellor, Sir Thomas More, or ‘Master Haunce’ as the English called him, arriving towards the close of 1526. Here Holbein was welcomed, and he made his home during this first visit to England. He painted portraits of many of the leading men of the day and produced drawings for a picture of the family of his patron. He soon became a renowned Northern Renaissance portrait painter of major contemporary figures. His work typically includes amazing details showing natural reflections through glass or the intricate weave of an elegant tapestry. By 1537, Holbein’s popularity had grown so much that he had come to the notice of Henry VIII, and he was established as court painter, a position he held until his death.

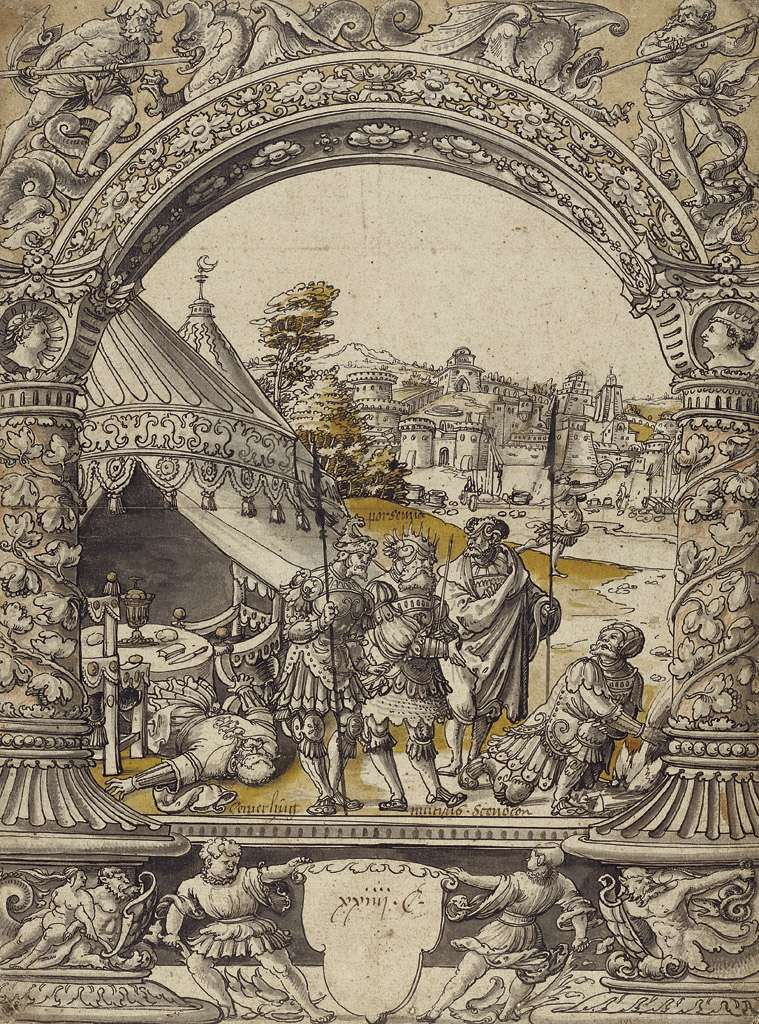

83. Master from Konstanz (Christoph Bockstorffer), c. 1480/1489-1553, Swiss. Mucius Scaevola Thrusting His Right Hand into the Flames before Lars Porsenna, c. 1530-1540. Pen and black ink, grey, and two shades of yellow wash and red chalk, 43.7 x 32.7 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Northern Renaissance.

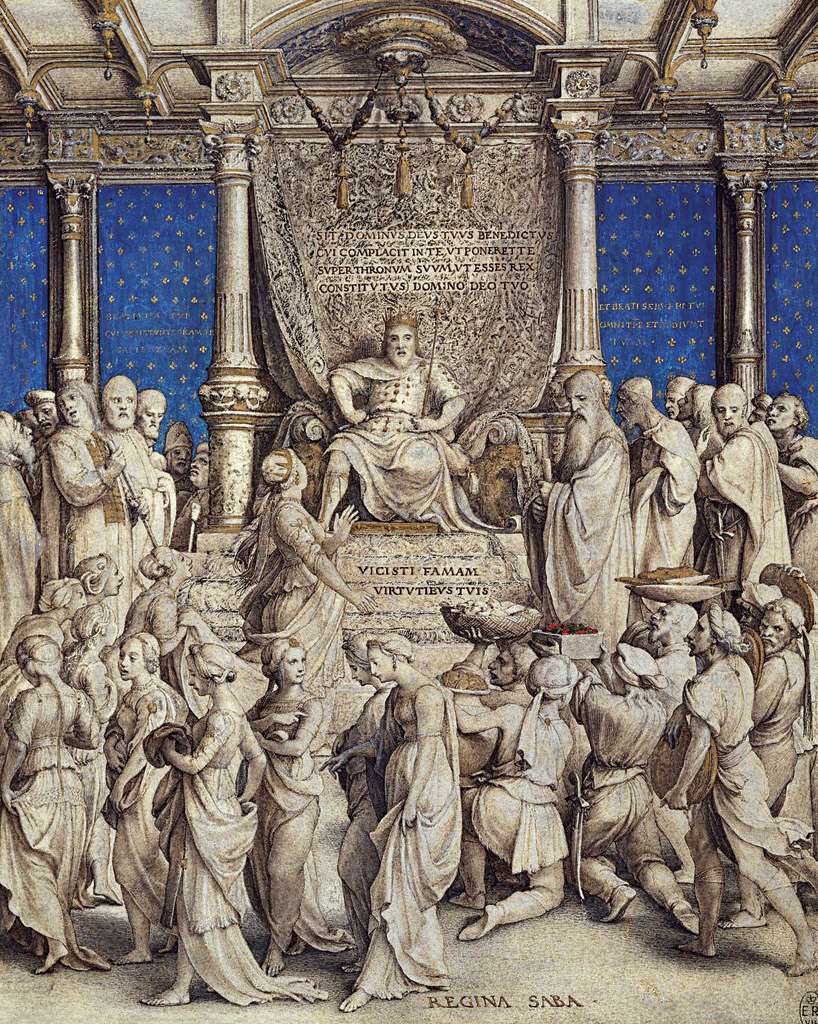

84. Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497-1543, German. Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, c. 1534. Brown and grey wash, blue, red and green bodycolour, white heightening, gold, pen and black ink over metalpoint on vellum, 22.9 x 18.3 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Northern Renaissance.

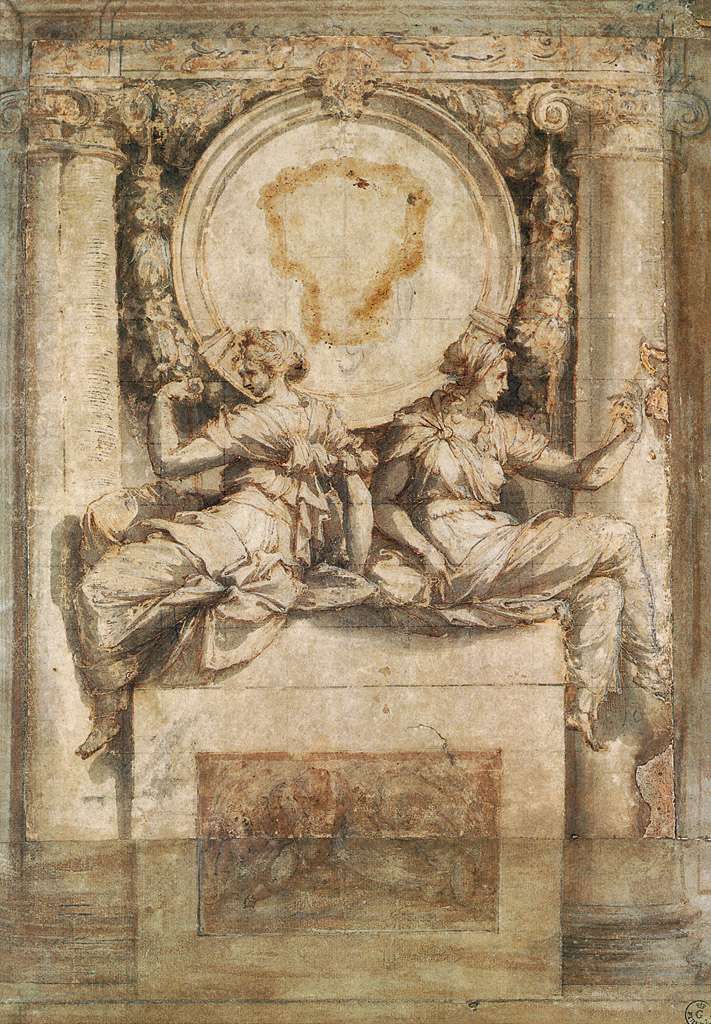

85. Perino del Vaga (Pietro Buonaccorsi), 1501-1547, Italian. Two Allegorical Figures for the Lintel of a Door, date unknown. Pen and brown watercolour on paper. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. High Renaissance.

86. Rosso Fiorentino (Giovanni Battista di Jacopo), 1494-1540, Italian. Bust of a Woman with an Elaborate Coiffure, c. 1530. Black chalk, some contours reinforced in pen and brown ink, and background tinted in brown wash (by another hand), 23.6 x 17.7 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Mannerism.

87. Giulio Romano, c. 1490-1546, Italian. Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, date unknown. Black pencil, pen, brown watercolour, and white lead on watermarked paper, 147 x 134 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Mannerism.

88. Correggio (Antonio Allegri), c. 1489-1534, Italian. Christ in Glory, 1520-1523. Red chalk, brown and grey wash, heightened with white bodycolour on pink ground, inscribed circle in brown ink, squared in red chalk, 14.6 x 14.6 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Mannerism.

89. Giorgio di Giovanni, 1538-1559, Italian. Studies of a Gentian, Moth, Birds, Cats, Interlacing Motif, and Greek Frets, c. 1530-1540. Pen and two colours of brown ink, brush and watercolour over leadpoint or black chalk, 18.2 x 26.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Renaissance.

90. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Composition with Animals, date unknown, Watercolour and gouache. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

91. Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497-1543, German. Sir Thomas More (1478-1535), c. 1526-1527. Black and coloured chalks, and brown wash, 37.6 x 25.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Northern Renaissance.

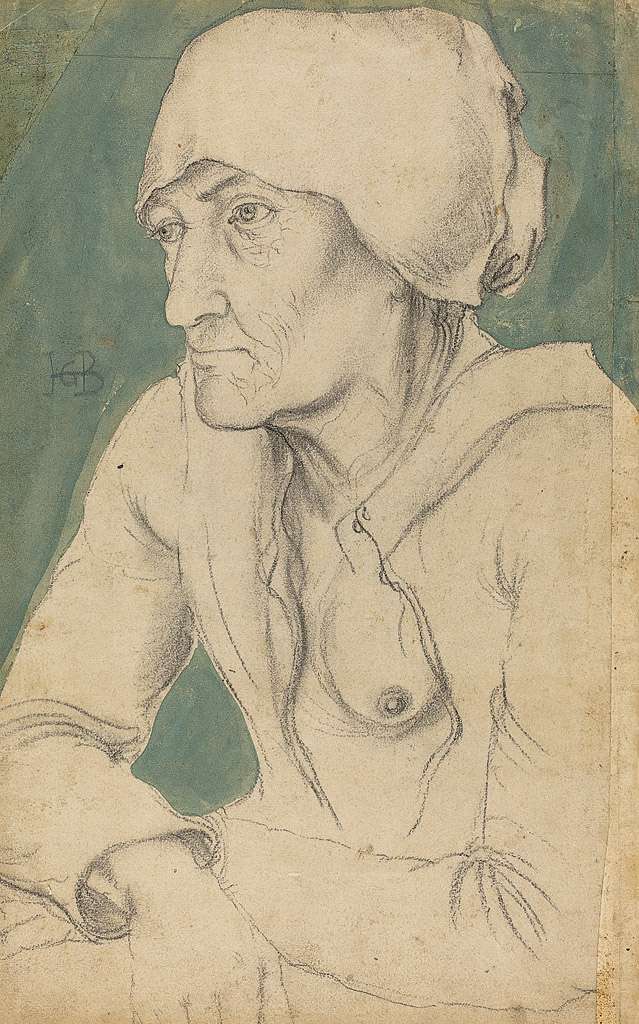

92. Hans Baldung, known as Grien, 1484/1485-1545, German. Half-Figure of an Old Woman with a Cap, c. 1535. Black chalk with green wash (added by a later hand), 39.6 x 23.6 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

93. François Clouet, c. 1516-1572, French. Portrait of Marguerite of France, Daughter of Louis II, Prince of Condé, Duke of Savoy, date unknown. Pencil, red chalk and touches of watercolour. Musée Condé, Chantilly. Mannerism.

94. Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497-1543, German. Elizabeth, Lady Vaux (1509-1556), c. 1536. Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, wash, pen and ink, brush and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper, 28.1 x 21.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Northern Renaissance.

95. Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497-1543, German. James Butler, later 9th Earl of Ormond and 2nd Earl of Ossory (c. 1496-1546), c. 1537. Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, red, blue-grey, and brown wash, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper, 40.1 x 29.2 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Northern Renaissance.

96. Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497-1543, German. Thomas, 2nd Baron Vaux (1509-1556), c. 1533. Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, white and yellow bodycolour, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper, 27.9 x 29.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Northern Renaissance.

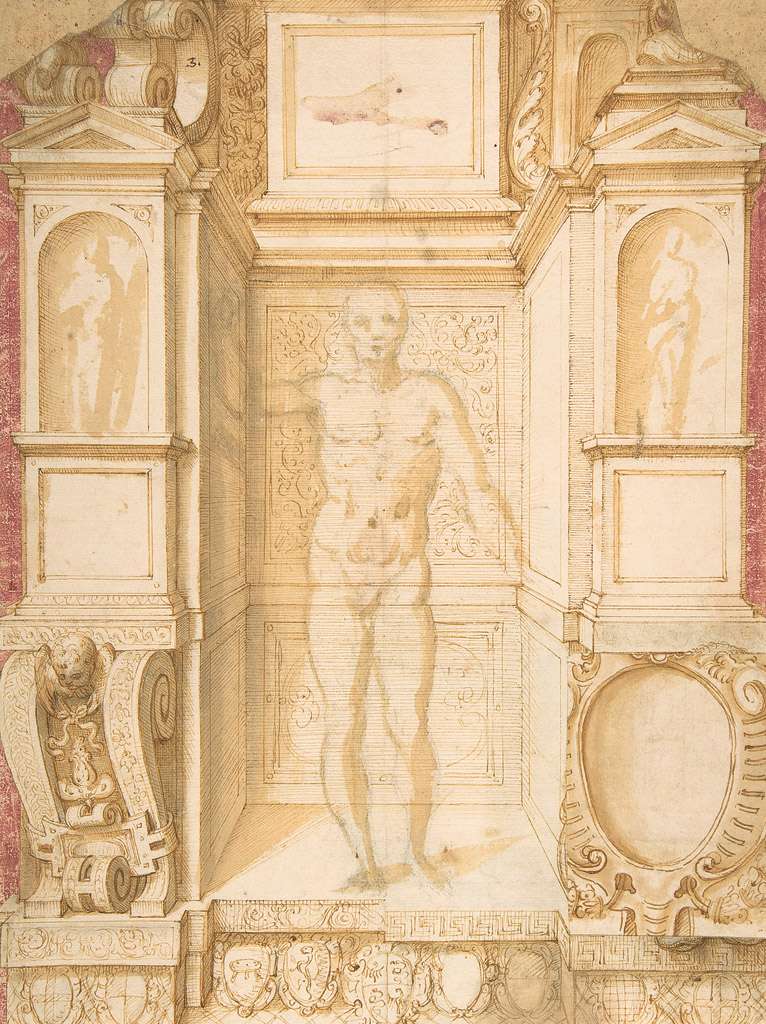

97. Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola), 1503-1540, Italian. Study of a Figure in an Architectural Setting, c. 1531-1533. Black chalk underdrawing, pen and ink, with wash and white heightening, 9.4 x 6.4 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Mannerism.

98. Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola), 1503-1540, Italian. Study of a Figure in an Architectural Setting, c. 1531-1533. Black chalk underdrawing, pen and ink, with wash and white heightening, 9.3 x 6.9 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Mannerism.

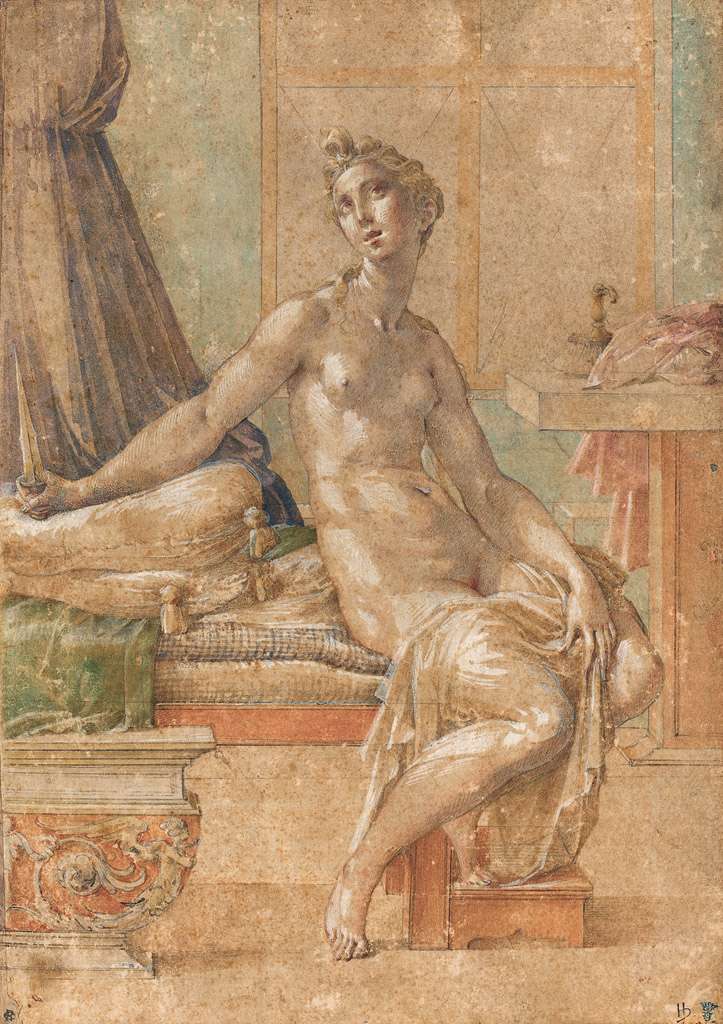

99. Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola), 1503-1540, Italian. Lucretia, c. 1539. Watercolour heightened with white over black chalk, 29.8 x 20.9 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Mannerism.

100. Michele da Verona, c. 1470-1536/1544, Italian. Madonna and Child with Saints Roch and Sebastian, date unknown. Tip of the brush and brown ink, brown and some blue wash, heightened with white, on paper tinted brown, 24.5 x 37.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Renaissance.

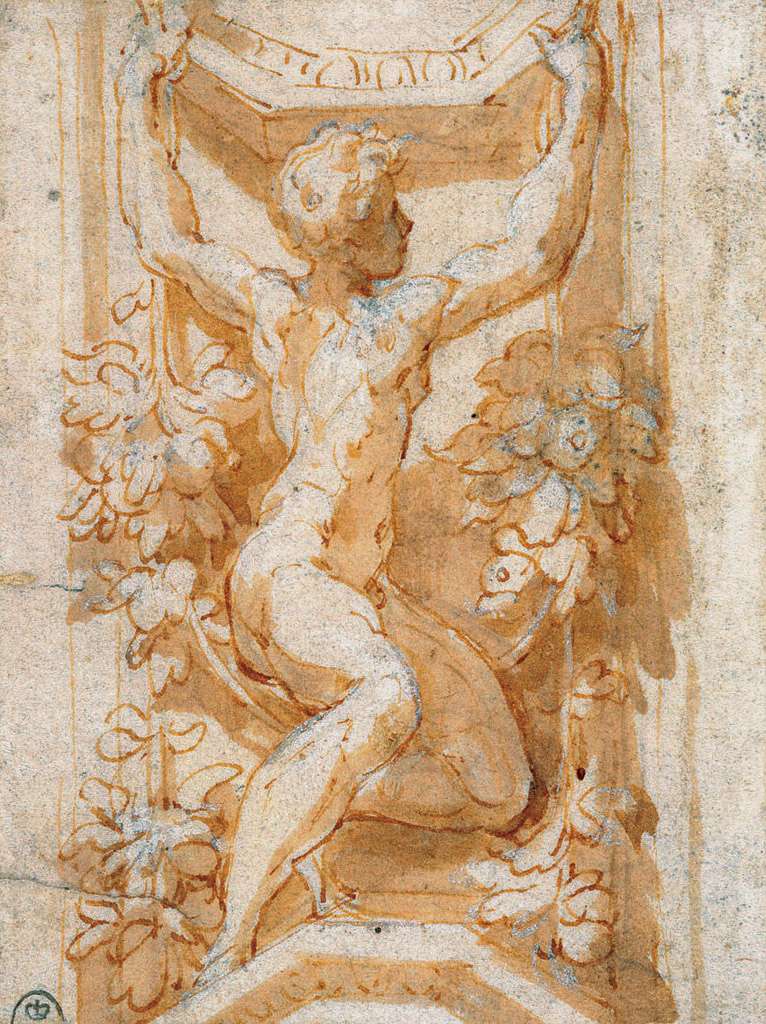

101. Nicolò dell’Abate, 1509/1512-1571, Italian. The Rape of Ganymede, c. 1545. Pen and brown ink with brown wash and watercolour over traces of black chalk, heightened with white on laid paper washed light brown, laid down, 38.9 x 28.9 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Mannerism.

102. Attributed to Jörg Breu the Younger, c. 1510-1547, German. Joseph Interpreting the Dreams of Pharaoh, c. 1534-1547. Distemper on canvas, 171.8 x 145.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

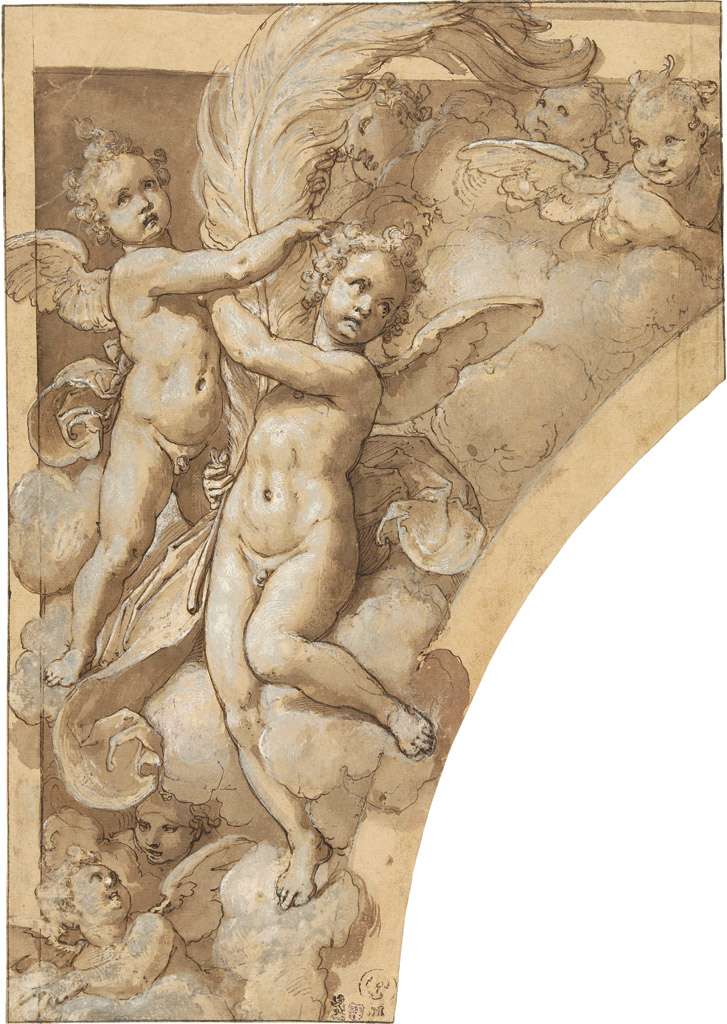

103. Taddeo Zuccaro, 1529-1566, Italian. Flight of Angels, Two Holding a Large Feather, 1556-1558. Gouache and ink on paper, 34.7 x 24.5 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. High Renaissance.

104. Lambert van Noort, c. 1520-1570/1571, Dutch. Breaking on the Wheel, 1555. Pen and brown ink, blue wash, heightened with white keys, very low traces of preliminary drawing in black chalk, diameter: 26.7 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Northern Renaissance.

105. Lambert van Noort, c. 1520-1570/1571, Dutch. St George and the Sorcerer of Dacian, 1555. Pen and brown ink, brush and blue wash, touches of white heightening, extremely faint traces of preliminary drawing in black chalk, diameter: 26.7 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

106. Hanns Lautensack, c. 1520-1564/1566, German. Imaginary Landscape, 1543. Pen and dark brown ink and brush and grayish blue watercolour, washed in blue, heightened with brush and opaque white, on greenish blue prepared paper, 14.4 x 21.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

107. Étienne Delaune, 1518-1583, French. Allegory of Religion, date unknown. Pen and brown ink, watercolour and gold lead on vellum, 33.5 x 43.4 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Mannerism.

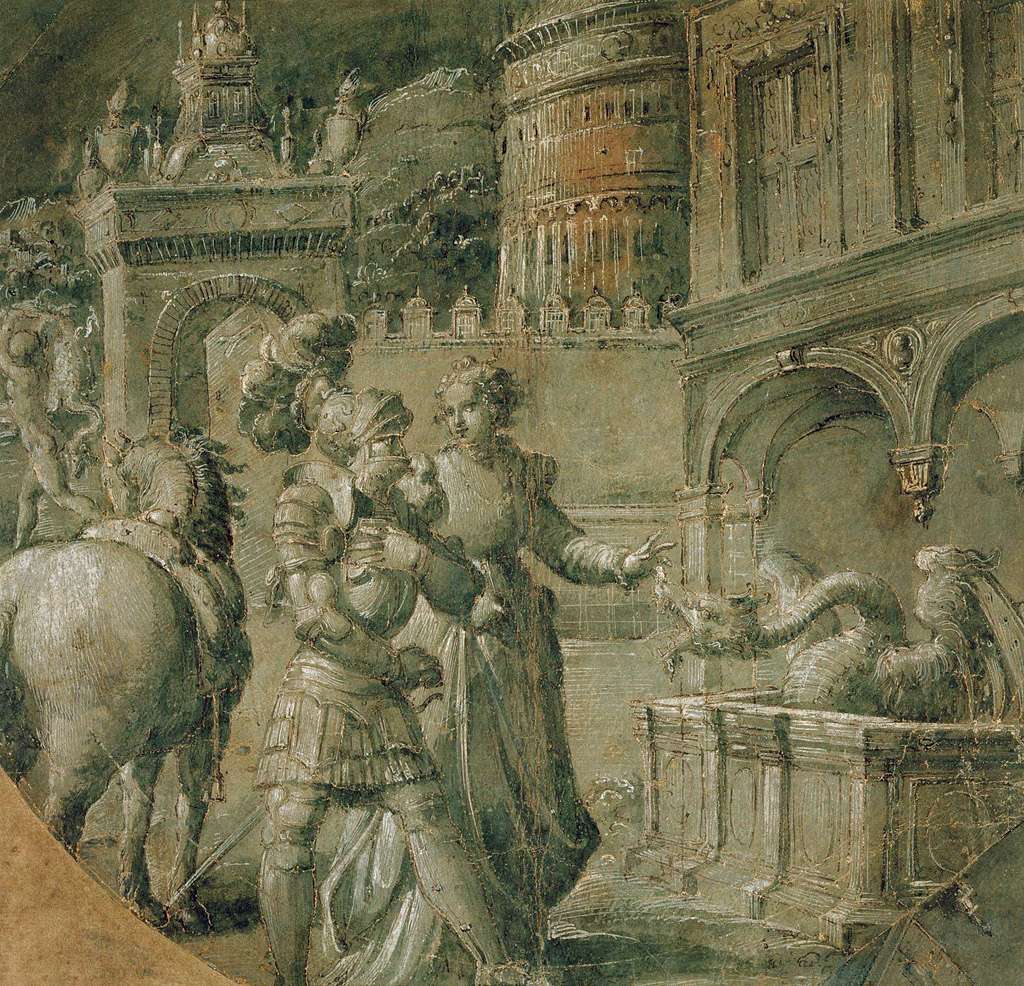

108. Nicolò dell’Abate, 1509/1512-1571, Italian. A Scene from Orlando Innamorato, c. 1545. Pen and ink with dark green wash and white heightening, on paper coated with a green preparation, the outlines pricked, 33.2 x 34.9 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Mannerism.

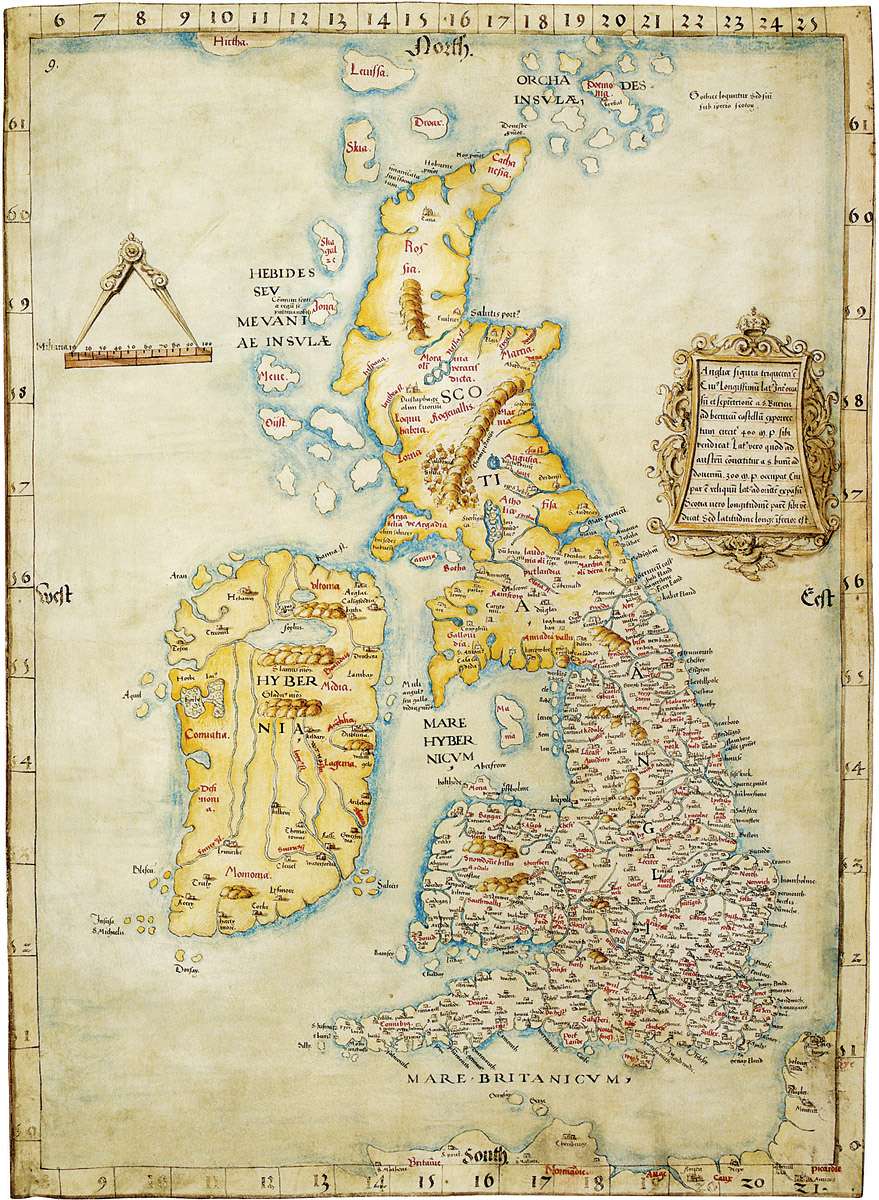

109. Anonymous, English. Anglia Figura, 1535-1546. Ink and watercolour on vellum, 63.5 x 42 cm. British Library, London.

110. Nicholas Hilliard, 1547-1619, English. Elizabeth I. (1533-1603), c. 1565. Watercolour on vellum laid on playing card, diameter: 4.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London. English Renaissance.

111. Nicholas Hilliard, 1547-1619, English. Elizabeth I. (1533-1603), c. 1560-1565. Watercolour on vellum laid on card, diameter: 5.2 cm. The Royal Collection, London. English Renaissance.

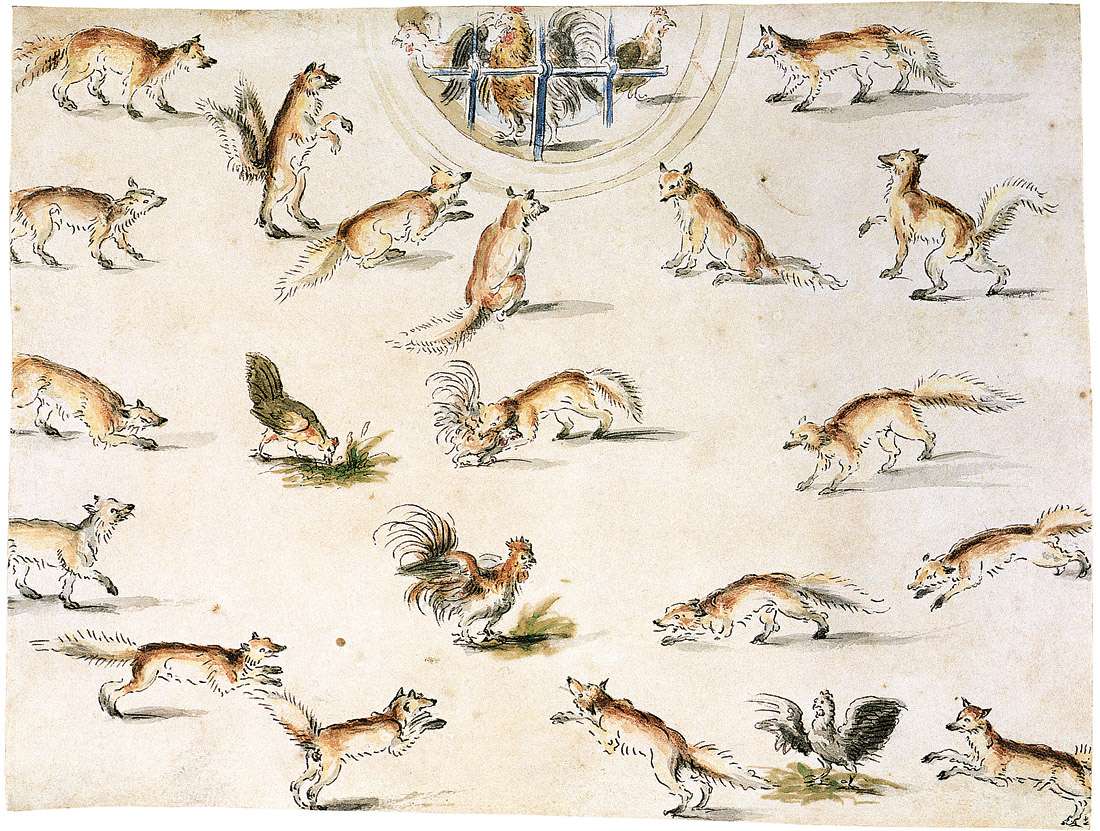

112. Lucas Cranach the Younger, 1515-1586, German. Study Sheet of Foxes, Chickens and Cockerels, c. 1565-1570. Lead point, pen, brown ink and watercolour, 21.3 x 28.7 cm. Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig. Northern Renaissance.

113. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Common Pheasant, date unknown. Watercolour. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

GIUSEPPE ARCIMBOLDO

(MILAN, C. 1527-1593)

At his debut, Arcimboldo’s contemporaries could not have imagined he would become famous for that which he is now. His youthful works were normally made for cathedrals in Milan or Monza, but it is from 1562, when he was summoned to the Imperial Court in Prague, that his style and subjects changed. For the court he imagined original and grotesque fantasies made of flowers, fruit, animals, and objects to compose a human portrait. Some were satiric portraits and others were allegorical personifications.

If his work is now regarded as a curiosity of the 16th century, it actually finds its roots in the context of the end of the Renaissance. At that time, collectors and scientists started to pay more attention to nature, looking for natural curiosities to exhibit in their curio cabinets.

114. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Wild Boar, date unknown. Watercolour. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

115. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Chamois and Ibex, date unknown. Watercolour. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

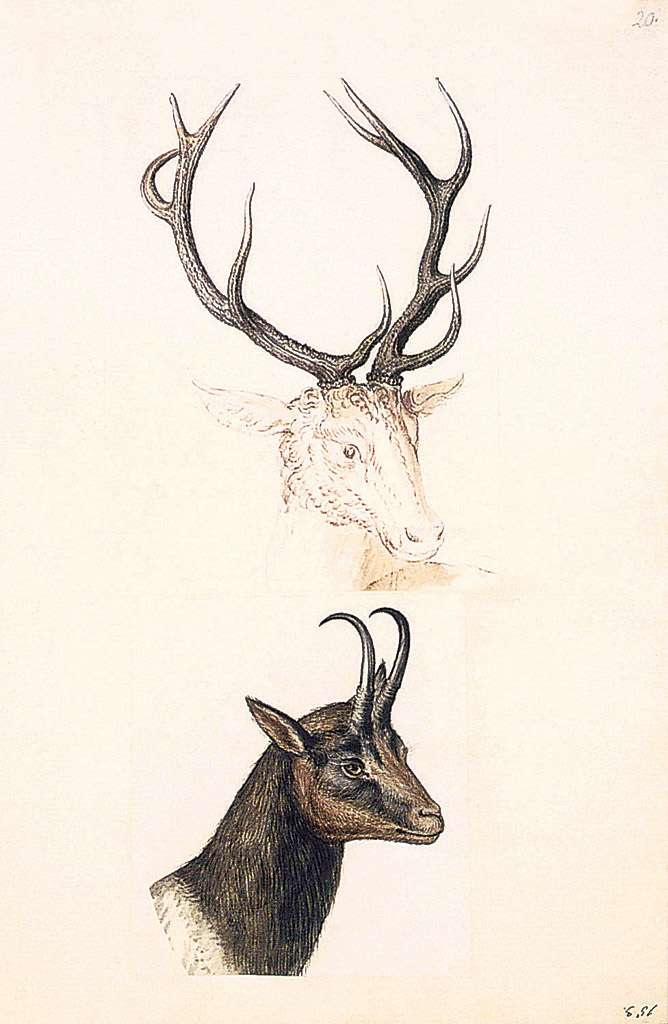

116. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Study of a Deer and a Goat, date unknown. Watercolour on parchment. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

117. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Aplomado Falcon, date unknown. Watercolour. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

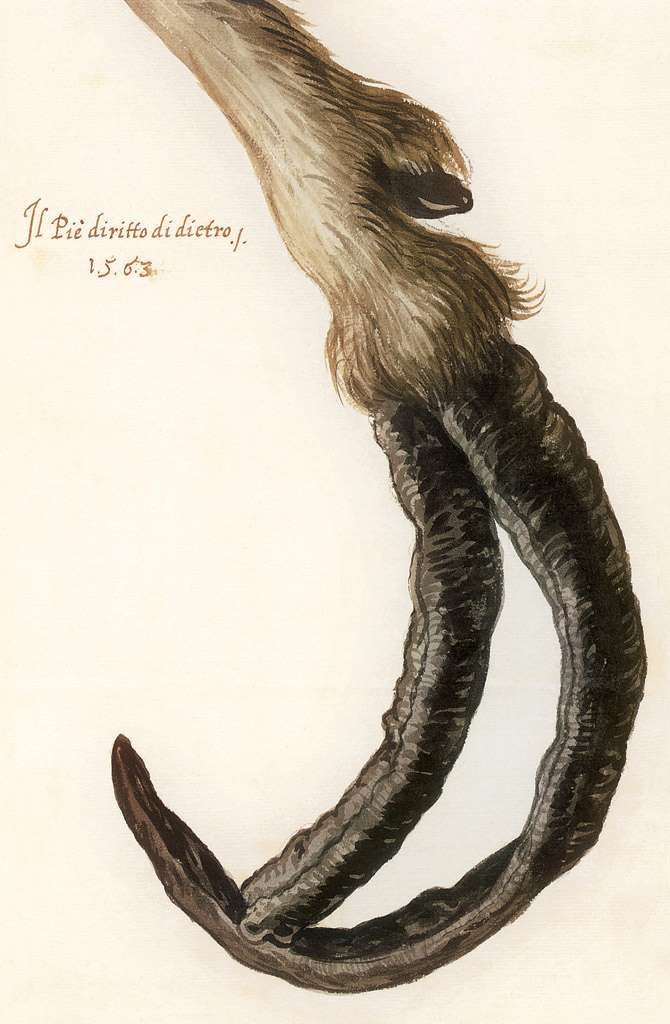

118. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Study of a Goat’s Deformed Hoof, 1563. Watercolour and gouache. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

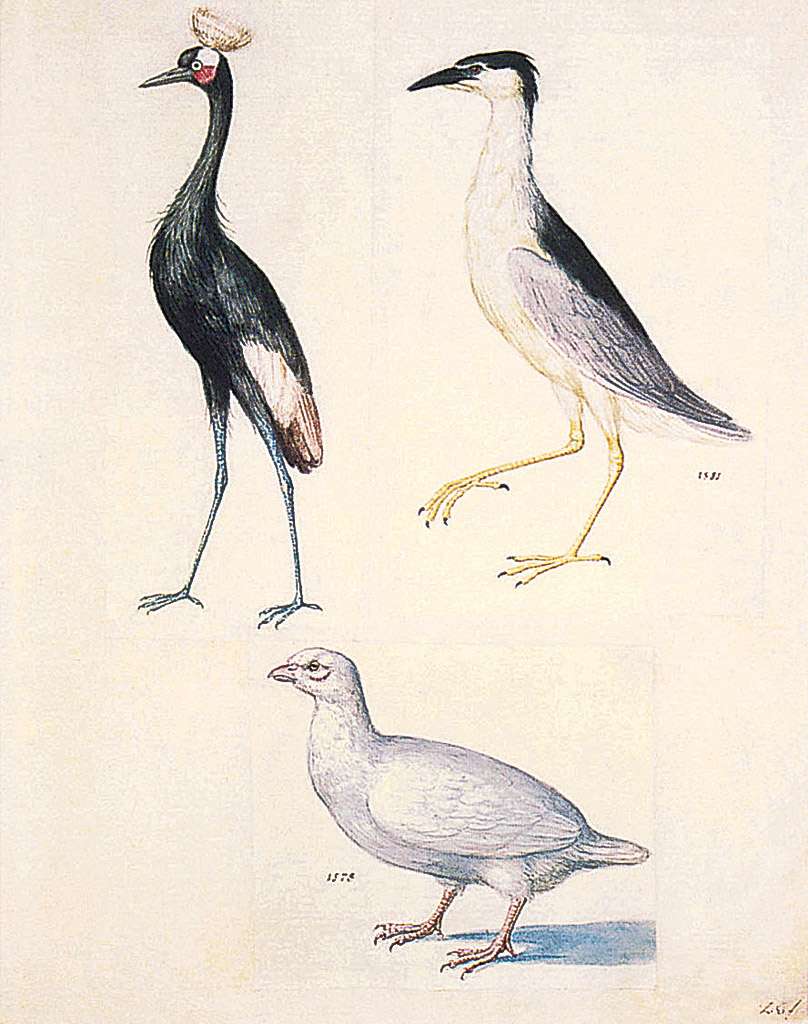

119. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Study of Birds, 1578. Watercolour on parchment. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

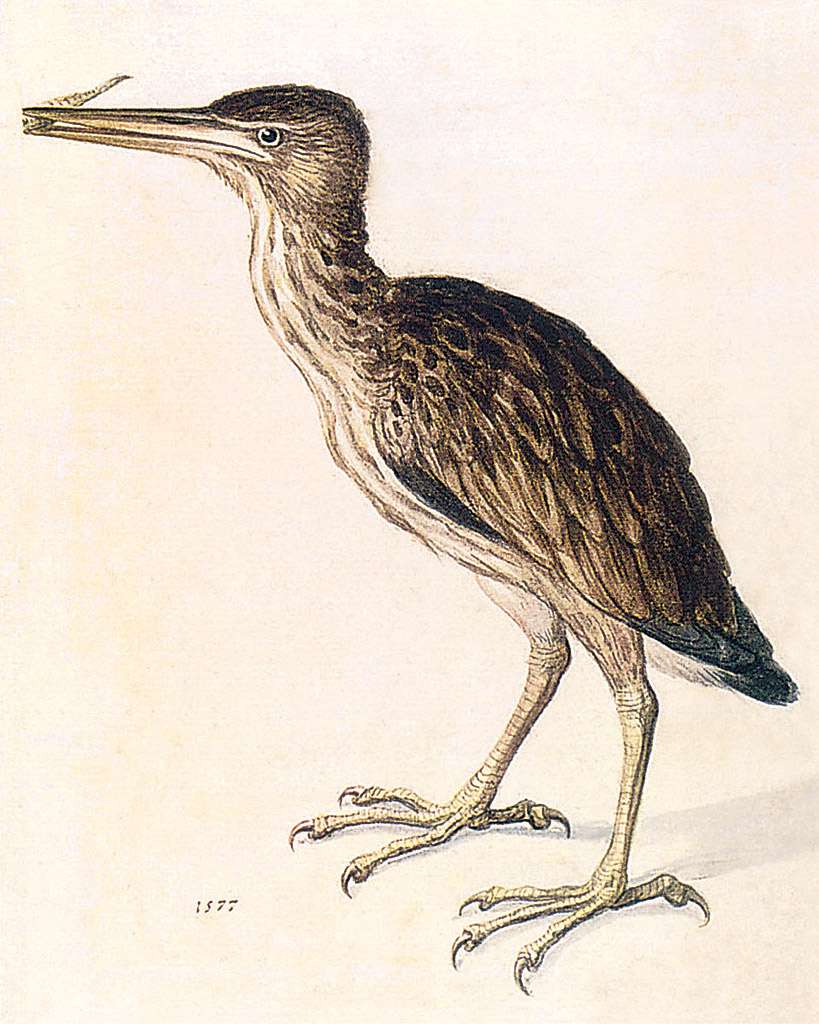

120. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Bird Study, 1577. Watercolour on parchment. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

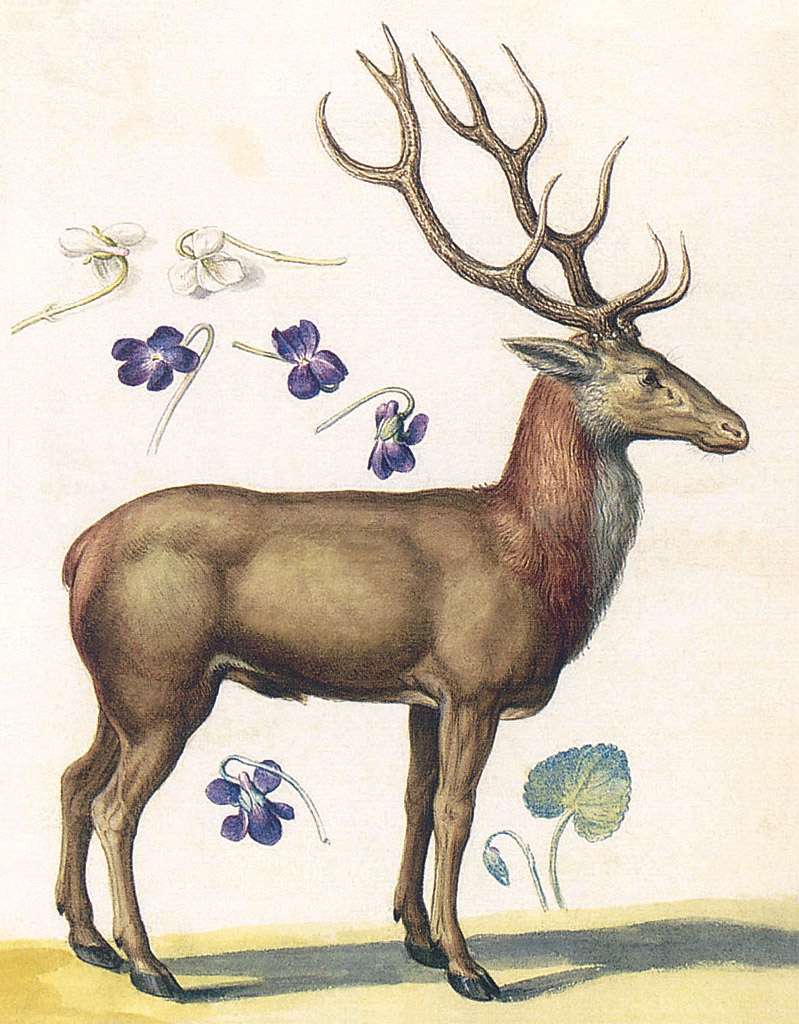

121. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Red Deer, date unknown. Watercolour. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

122. Jan van der Straet (Giovanni Stradano), 1523-1603, Flemish. An Alchemist’s Laboratory, 1570. Pen and brown ink with brown wash over black chalk, heightened with white, on yellow prepared paper, 30.2 x 21.9 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Mannerism.

123. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Study of a Figure in a Niche (Saint Ambrose; recto), 1577. Watercolour on parchment, 35.1 x 26.3 cm. Österreichische nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Mannerism.

124. Andrea Casalini, ?-1597, Italian. Design for the Pommel Plate of a Saddle from a Garniture of Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589), c. 1575-1580. Pen and brown ink, with color washes on paper, 49.5 x 39.2 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Renaissance.

125. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, Dutch. Windsor Castle Seen from the North with Figures in the Foreground, c. 1568. Pen and brown ink with brown and blue wash, 26.4 x 41.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Northern Renaissance.

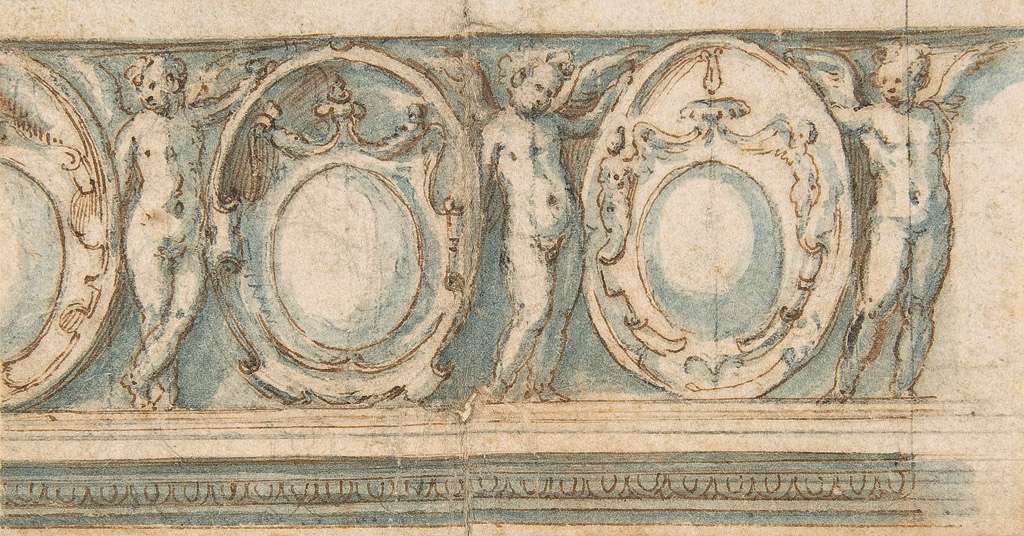

126. Attributed to Luzio Luzzi (Luzio Romano, Luzio da Todi), active 1519-1582, Italian. Design for a Decorated Frieze with Alternation of Cartouches and Winged Putti, 16th century. Pen and brown ink, brush and blue wash (over traces of leadpoint?), 6.6 x 12.6 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Mannerism.

127. Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, 1533-1588, French. A Sheet of Studies with French Roses and an Oxeye Daisy, c. 1570. Watercolour and gouache over black chalk, 20.6 x 15.6 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

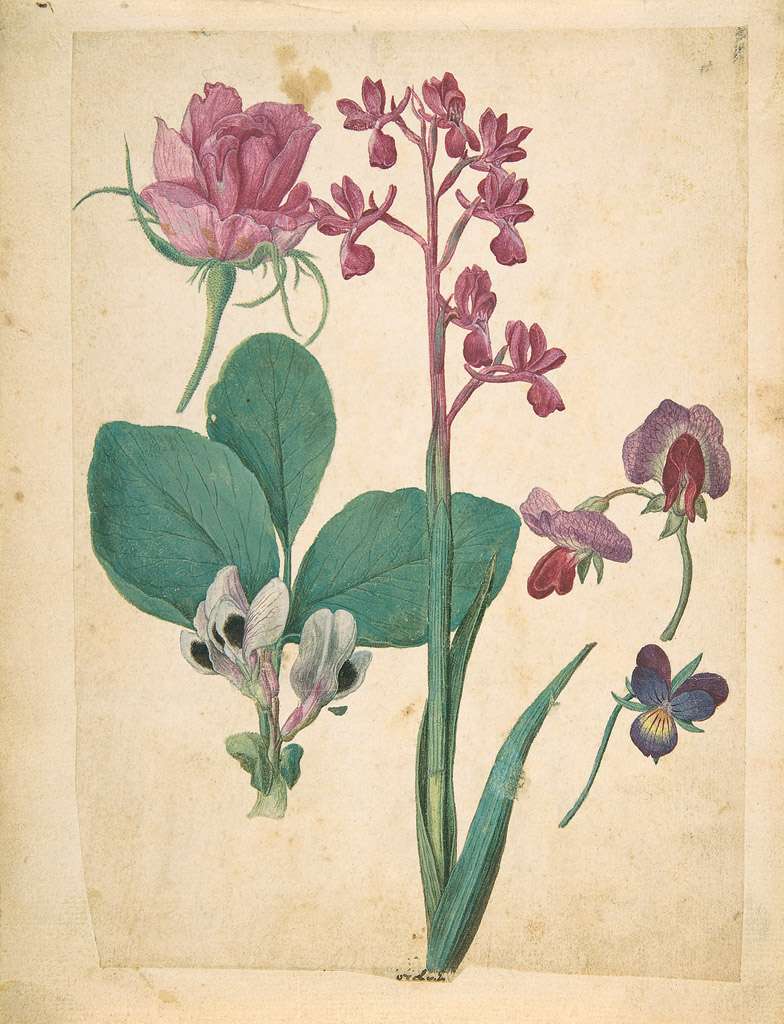

128. Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, 1533-1588, French. A Sheet of Studies of Flowers: A Rose, a Pansy a Sweet Pea, a Garden Pea, and a Lax-flowered Orchid, date unknown. Watercolour and gouache, over black chalk, 21.1 x 15 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

JACQUES LE MOYNE DE MORGUES

(DIEPPE, 1533 – LONDON, 1588)

Jacque Le Moyne de Morgues was a French cartographer and illustrator. He presumably worked in the court of Karls IX. In 1562, he took part in an expedition to the New World. In Florida, he was entrusted with the portrayal of the land and people and flora and fauna. These works were lost for posterity because they were destroyed during an attack by the Spanish. In the court of Elizabeth I. of England, he began to occupy himself with botanical studies, which were rediscovered in the conservatory in 1922, and in which the significance of his watercolours was manifested. In 1585, he met another great cartographer, John White, who drew much inspiration from Jacque Le Moyne de Morgues.

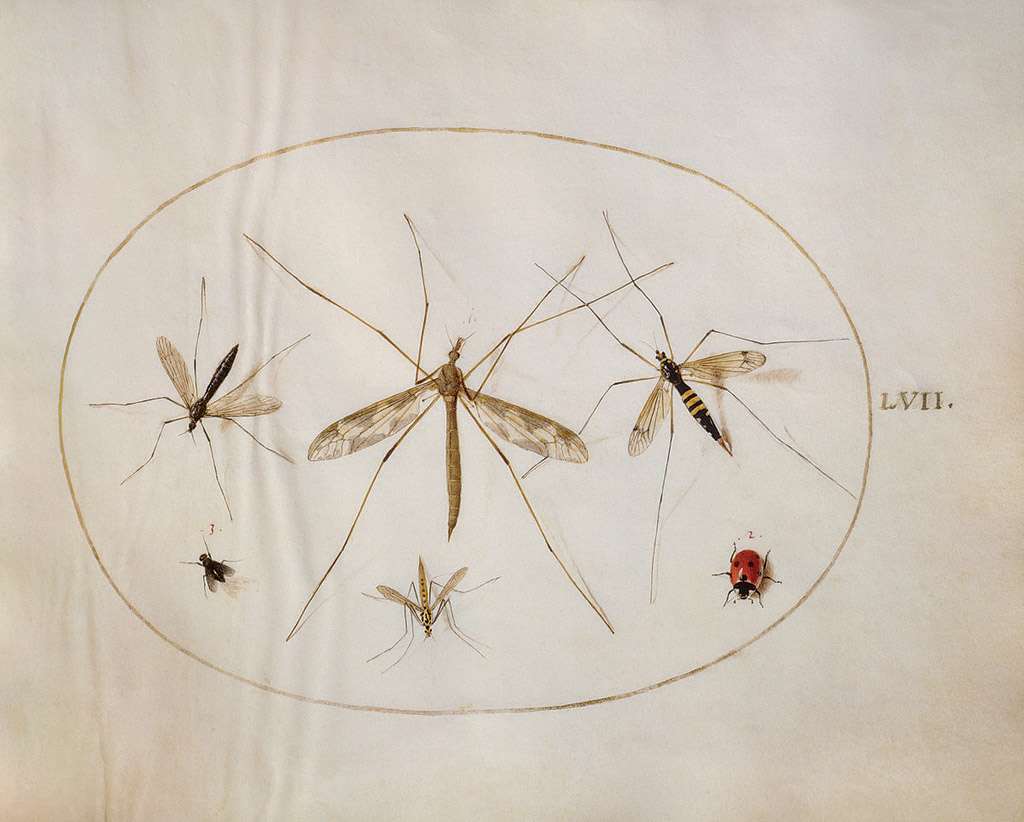

129. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, Dutch. Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate LVII, c. 1575-1580. Watercolour and gouache with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

130. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, Dutch. Animalia Qvadrvpedia et Reptilia (Terra): Plate LIII, c. 1575-1580. Watercolour and gouache with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

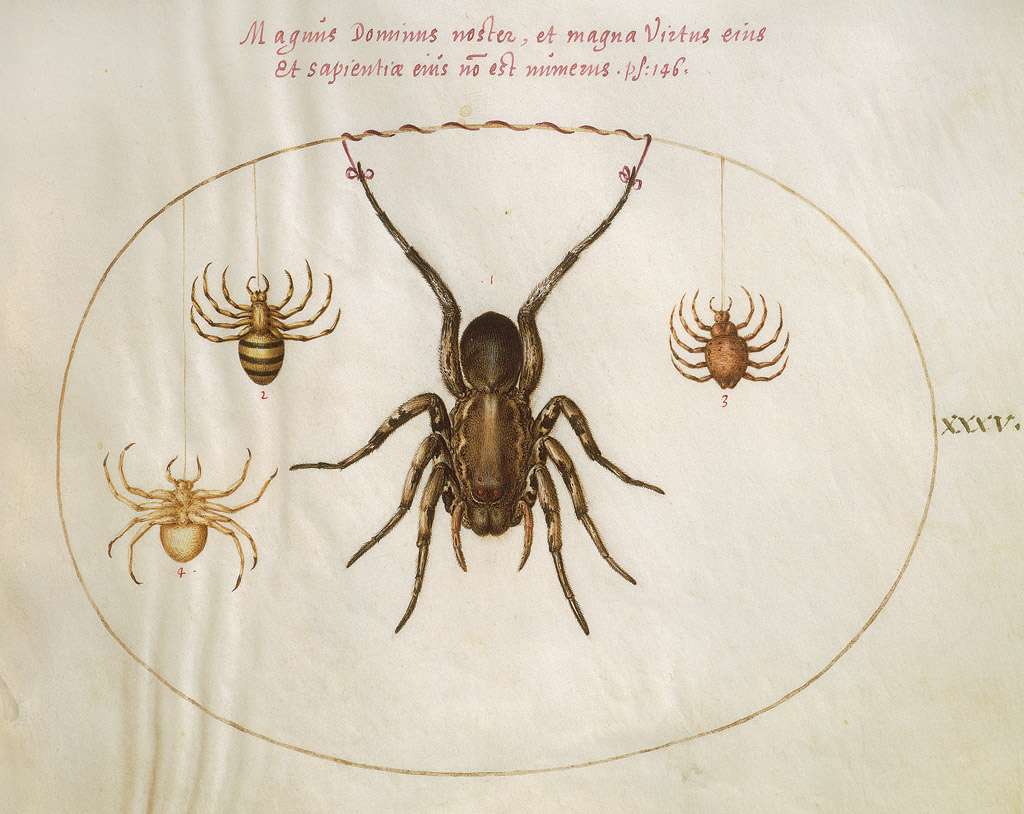

131. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, Dutch. Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate XXXV, c. 1575-1580. Watercolour and gouache with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

132. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, Dutch. Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate V, c. 1575-1580. Watercolour and gouache with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

133. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, Dutch. Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate V, c. 1575-1580. Watercolour and gouache with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

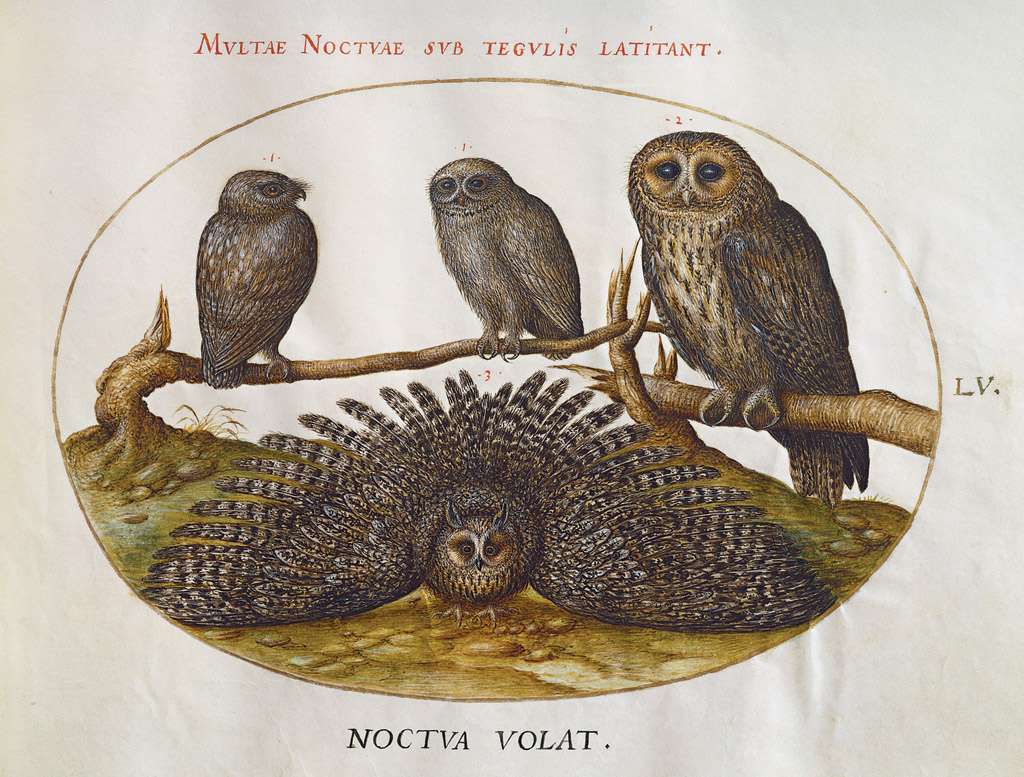

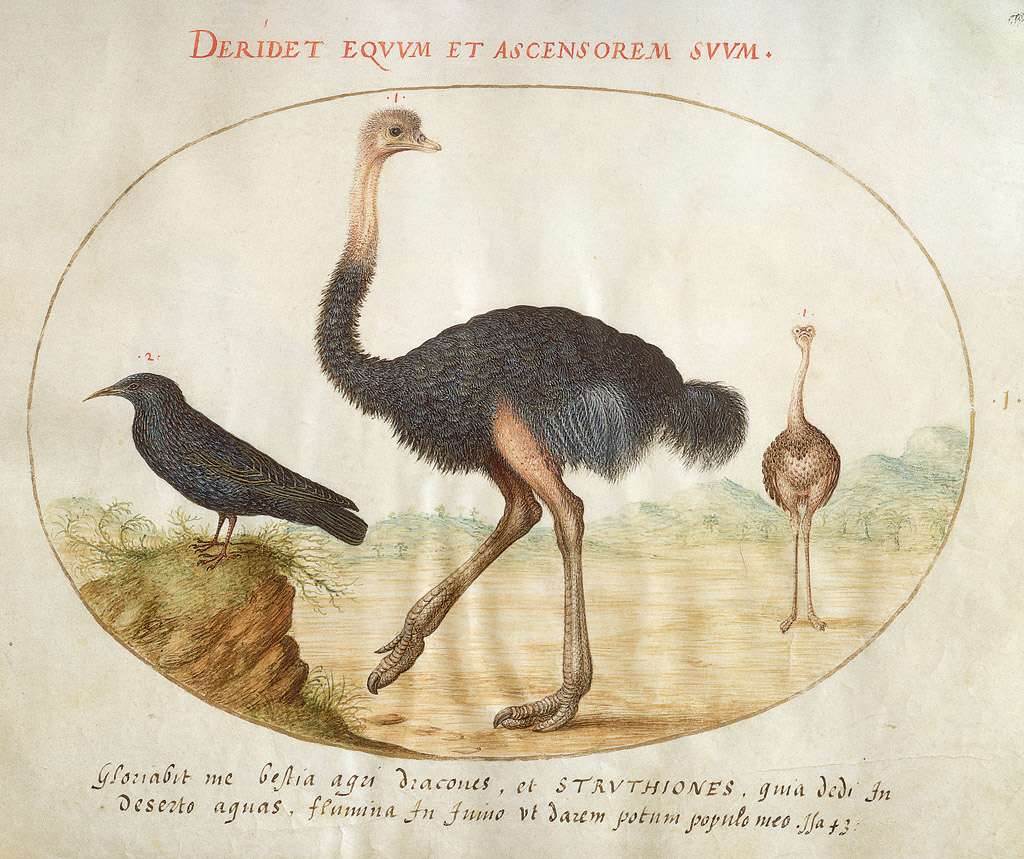

134. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, Dutch. Animalia Volatilia et Amphibia (Aier): Plate I, c. 1575-1580. Watercolour and gouache with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

135. Nicholas Hilliard, 1547-1619, English. Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587), c. 1578-1579. Watercolour on vellum laid on card, 4.5 x 3.7 cm. The Royal Collection, London. English Renaissance.

136. Nicholas Hilliard, 1547-1619, English. Elisabeth I (1533-1603), c. 1580-1585. Watercolour on vellum laid on paper, 3.8 x 3.3 cm. The Royal Collection, London. English Renaissance.

137. Nicholas Hilliard, 1547-1619, English. Portrait of a Lady, Possibly Frances Walsingham (?-1632), c. 1590. Watercolour on vellum, 5.7 x 4.7 cm. The Royal Collection, London. English Renaissance.

138. Nicholas Hilliard, 1547-1619, English. Portrait of a Lady, Perhaps Penelope, Lady Rich (1563-1607), c. 1589. Watercolour on vellum laid on card, 5.7 x 4.6 cm. The Royal Collection, London. English Renaissance.

139. Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1527-1593, Italian. Self-Portrait, c. 1571-1576. Pen and blue wash, 23.1 x 15.7 cm. Narodni Galerie, Prague. Mannerism.

140. Melchior Bocksberger, c. 1530-1587, Austrian. The Conversion of St Paul, date unknown. Pen and brown ink, brush and blue watercolour, 23 x 33 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Renaissance.

141. Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, 1533-1588, French. Figs (Ficus carica), c. 1585. Watercolour and gouache on paper, 21.5 x 13.9 cm. British Museum, London.

142. Jacopo Ligozzi, 1547-1626/1627, Italian. Botanical Specimen (Motherwort or “Leonurus cardiaca”), 1577-1591. Brush with watercolour and gouache on vellum, 53.3 x 33.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Mannerism.

143. Hans Hoffmann, c. 1530-1591/1592, German. A Small Piece of Turf, 1584. Brush with gouache and watercolour over traces of charcoal underdrawing, 21.5 x 32.6 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

144. Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, 1533-1588, French. A Kingfisher on a Branch, date unknown. Watercolour and gouache over traces of black chalk, 11.5 x 18 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

145. Hans Hoffmann, c. 1530-1591/1592, German. Red Squirrel, 1578. Watercolour and gouache on vellum, 25 x 17.8 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

146. John White, active 1577-1593, English. The Indian Village Secoton, c. 1585. Watercolour on paper, 31.1 x 19.7 cm. British Museum, London.

147. John White, active 1577-1593, English. Map of the North Carolina Coast, 1585-1593. Pen and brown ink, watercolour over graphite pencil, silver and gold accentuated, 47.8 x 23.5 cm. British Museum, London.

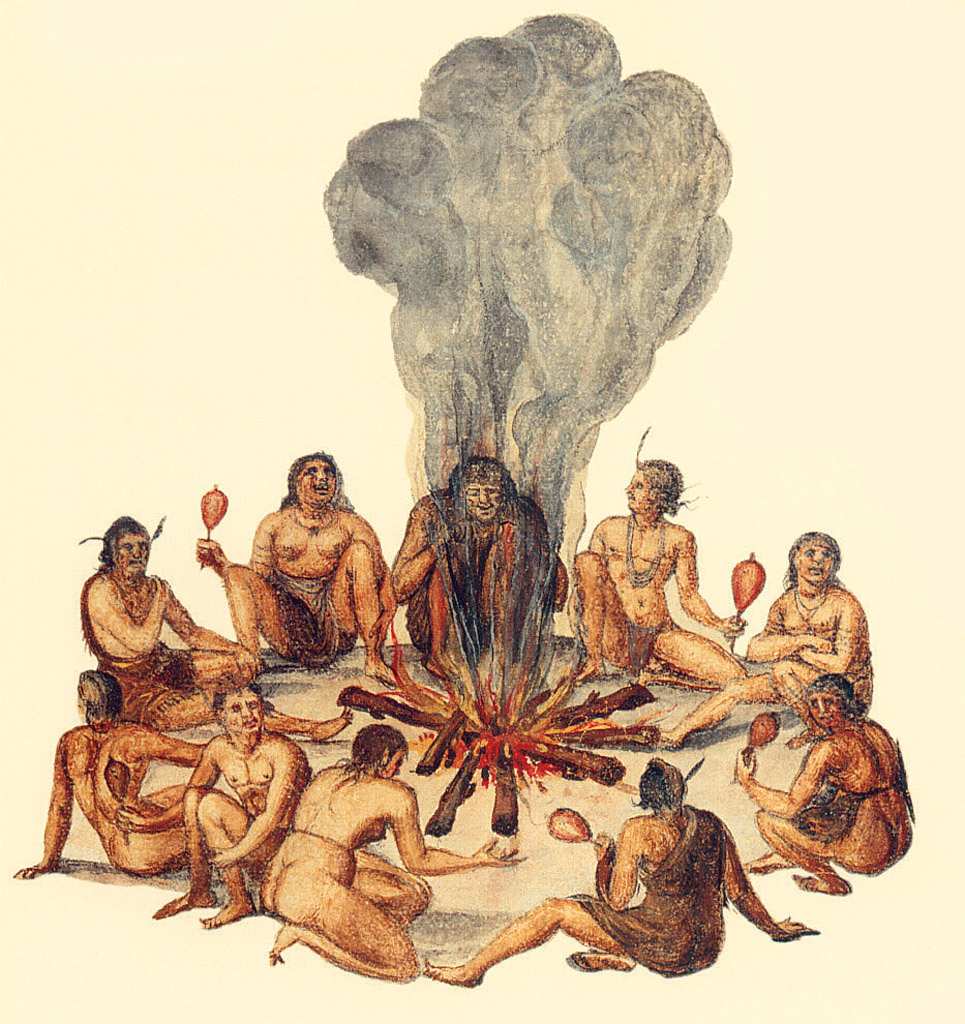

JOHN WHITE

(TRURO?, C. 1540-1593)

John White embarked on an expedition to North America in 1585. He and his fellow travellers landed on the shores of the Roanoke Island in what today is North Carolina. During the course of his stay, he captured the geography and the indigenous people in watercolour. These paintings would later be distributed on a large scale and herald in the expeditions of the conquistadors of the 1800s. In 1587, John White was named the governor of Roanoke during a second trip. The inhabitants needed food immediately, and thus urged John White to return to England to request replenishments. His trip was postponed, and he finally returned to the island two years later, which, by that time, was deserted. Even though John White’s colony was a failure, his watercolour drawings, by which he immortalised them, are still one of the oldest iconographic sources that portray North America.

148. Jacob Halder, active 1557-1607, English. Almain Armourer’s Album; The Jacob Album; ‘The Earle of Cumberland’, c. 1587. Pen, ink, and watercolour on paper, two sheets, 42.5 x 28.8 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. English Renaissance.

149. John Darby, active 1582-1609, English. Estate Map of Smallburgh, Norfolk, 1582. Ink and tempera on parchment, 102.2 x 173 cm. British Library, London.

150. John White, active 1577-1593, English. Mother and Child of the Secotan Indians in North Carolina, c. 1585. Watercolour. British Museum, London.

151. John White, active 1577-1593, English. Indian Conjurer, c. 1585. Watercolour on paper, 24.6 x 14.9 cm. British Museum, London.

152. John White, active 1577-1593, English. Ceremony of Secotan warriors in North Carolina, c. 1585. Watercolour. British Museum, London.

153. Jan Brueghel the Elder, 1568-1625, Flemish. View of Heidelberg, 1588-1589. Pen and brown ink, paintbrush, blue and brown wash, and gold lead, 20 x 30.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Mannerism.

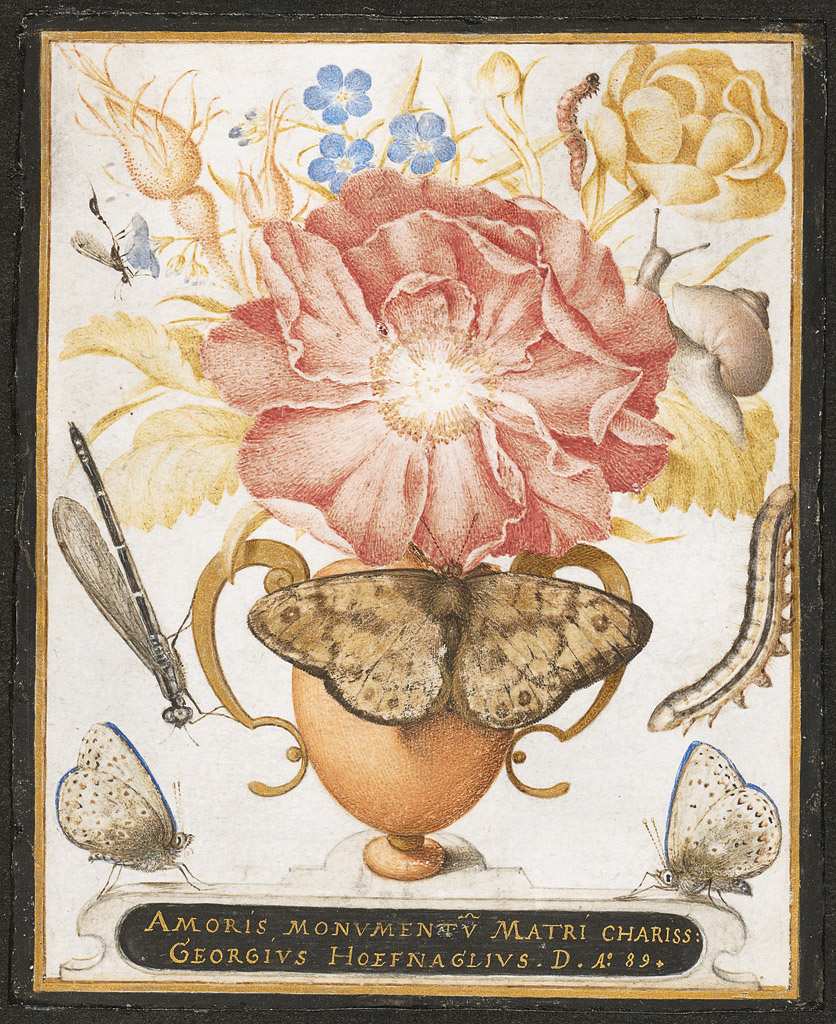

154. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, Dutch. Still Life with Flowers, a Snail and Insects, 1589. Watercolour, gouache, and shell gold on vellum, 11.7 x 9.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

155. Jacopo Ligozzi, 1547-1626/1627, Italian. A Janissary “of War” with a Lion, c. 1577-1580. Watercolour, gouache, gold paint, gum arabic, and burnishing, 28.2 x 22.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Mannerism.

156. Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti), 1518-1594, Italian. Six Figures in a Landscape, date unknown. Chalk and watercolour. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Mannerism.

TINTORETTO

(JACOPO ROBUSTI)

(1518-1594 VENICE)

With his father being a dyer of silk (tintore), Tintoretto was given the nickname, Il Tintoretto, ‘The Little Dyer’ in his youth. He became the most important Italian Mannerist painter of the Venetian school. St Mark, the patron saint of Venice, is thematic in two of his most important works. He focused most of his major pieces on various religious themes. With his talent already recognisable in his younger years, Tintoretto worked with Titian. After only ten days in the latter’s studio, Titian refused to teach him further; Tintoretto had already created his own style. His early works were marked by Mannerism, classic themes were employed in his works such as Venus und Mars (1538) as well as the extraordinarily erotic style in Leda and the Swan (1552). His later works would show him to be the predecessor of Baroque. In regard to his career, a story tells us that the Brothers of the Confraternity of San Rocco gave Tintoretto a commission for two pictures in their church and then invited him to enter a competition with Veronese and others for the decoration of the ceiling in the hall of their school. When the day arrived, the other painters presented their sketches, but Tintoretto, being asked for his, removed a screen from the ceiling and showed it already painted. ‘We asked for sketches’, they said. ‘That is the way’, he replied, ‘I make my sketches’. They still demurred, so he made the picture a present, and by the rules of their order they could not refuse a gift. In the end they promised him the painting of all the pictures they required, and during his lifetime he covered their walls with sixty large compositions.

Yet it is his phenomenal energy and the impetuous force of his work which is particularly characteristic of Tintoretto and earned for him the sobriquet among his contemporaries of Il Furioso. He painted an incredibly large number of pictures, and on such a vast scale, that some do not seem to be of great patience and attention to detail, and they show the effects of over-haste and extravagance, which caused Annibale Carracci to rather poignantly quip, ‘While Tintoretto was the equal of Titian, he was often inferior to Tintoretto’. The main interest of his work is his love for shortcuts, and it is said that to help him with the complex poses he favoured, Tintoretto used to make small wax models which he arranged on a stage and experimented on with spotlights for effects of light and shade and composition. This method of composing explains the frequent repetition in his works of the same figures seen from different angles.

157. Gerrit Pietersz Sweelinck, c. 1566-1612, Dutch. The Adoration of the Shepherds, 1599. Pen and brown ink, brown-red wash, heightened with white gouache, 25 x 33 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

158. Aegidius Sadeler, 1568-1629, Dutch. Anagram in Honor of Charles III, Duke of Lorraine and Bar, c. 1590. Pen and brown, red, and black ink, brown wash, white gouache, 39 x 30.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Baroque.

159. Jacques Jonghelinck, 1530-1606, Dutch. The Goddess Diana, c. 1570-1580. Pen and brown ink, brown and blue washes, red chalk, white gouache, over black chalk, squared in black chalk, 34.5 x 21.2 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Mannerism.

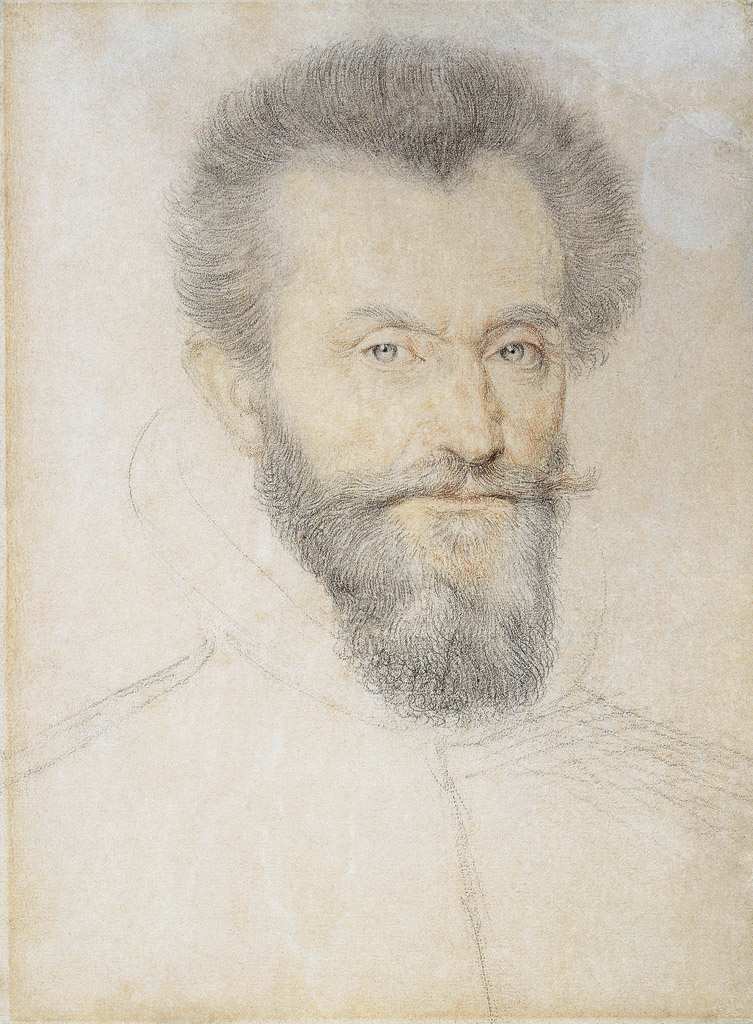

160. Attributed to François Quesnel, 1543-1619, French. A Portrait of a Bearded Man, c. 1590-1600. Black and red chalk with wash, 30.3 x 22.3 cm. The Royal Collection, London. French Renaissance.

161. Friedrich Sustris, c. 1540-1599, Dutch. Design for a Silver Statuette of Saint Michael, c. 1600. Pen, ink, and watercolour, 35.3 x 22.7 cm. Grafische Sammlung, Albertina, Vienna. Renaissance.

162. Paris Nogari, 1536-1601, Italian. The Circumcision, c. 1580. Pen and ink with wash and white heightening, over black chalk, on blue paper, 41.7 x 24.6 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Mannerism.

163. Joseph Heintz the Elder, 1564-1609, Swiss. The Daughters of the Po with River Gods, 1591. Pen and brown ink, brown wash and watercolour, heightened with white, red, and green gouache and indented for transfer on laid paper, 61.5 x 62.8 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Mannerism.

164. Hendrick Goltzius, 1558-1617, Dutch. Perseus and Andromeda, 1597. Pen and brown ink with brown wash, the flesh modelled with red chalk and red wash, white heightening, on buff paper; indented for transfer, 26.3 x 37.6 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Baroque.

165. Pieter Fransz Isaacsz, 1569-1625, Dutch. The Baptism of Christ, c. 1590. Black chalk, pen, brown ink, brown, indigo and green wash, 43.4 x 36.2 cm. École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris. Northern Renaissance.

166. Brunswick-Lüneburg Court Miniaturist, German. Frederick, Pfalzgraf of Zweibrücken (1557-1595), c. 1595. Watercolour on vellum, 7 x 5.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London.

167. Brunswick-Lüneburg Court Miniaturist, German. Sophia, Duchess of Saxe-Altenburg (1563-1590), c. 1595. Watercolour on vellum, 7 x 5.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London.

168. Brunswick-Lüneburg Court Miniaturist, German. William the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1535-1592), c. 1595. Watercolour on vellum, 7 x 5.6 cm. The Royal Collection, London.

169. Brunswick-Lüneburg Court Miniaturist, German. Frederick William I, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg (1562-1602), c. 1595. Watercolour on vellum, 7 x 5.7 cm. The Royal Collection, London.

170. Joris Hoefnagel, 1542-1600, German. Diana and Actaeon, 1597. Watercolour with gold lead, 22 x 33.9 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Mannerism.

171. Nicholas Hilliard, 1547-1619, English. George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland (1558-1605), c. 1590. Watercolour and gouache, gold and silver leaf on vellum, laid on fruitwood panel, 25.8 x 17.6 cm. Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. English Renaissance.

172. Battista Castello, 1547-1639, Italian. Returning the Keys to Saint Pierre, 1598. Parchment illumination, distemper, watercolour, 38.4 x 29.2 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Mannerism.

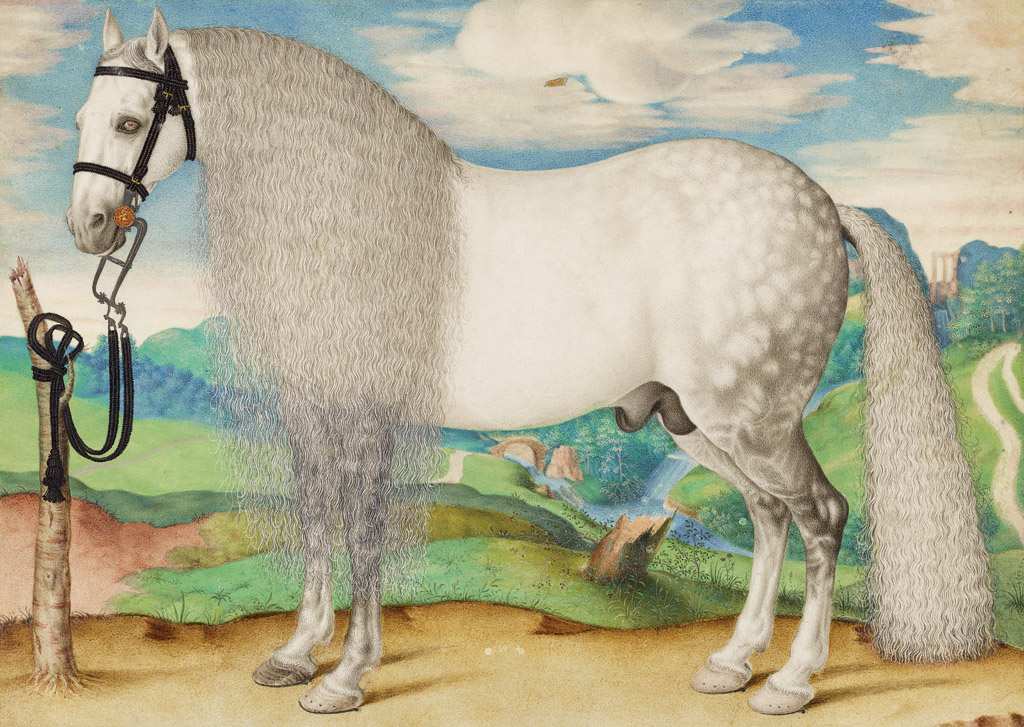

173. Anonymous, Czech. A Dappled Gray Stallion Tethered in a Landscape, c. 1584-1587. Watercolour and gouache, heightened with silver and gold on vellum, 19.5 x 27.5 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

174. Isaac Oliver, c. 1565-1617, English. A Young Man Seated Under a Tree, c. 1590-1595. Watercolour on vellum laid on card, 12.4 x 8.9 cm. The Royal Collection, London. English Renaissance.

175. Jan Brueghel the Elder, 1568-1625, Flemish. Landscape with Tobias and the Angel, c. 1595. Pen, brown ink, brown and blue wash, 20.2 x 31.3 cm. Szépmuvészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Northern Rennaissance.

176. Bernardino Passeri, c. 1540-1596, Italian. The Parables, first published in 1593. Watercolour. The Royal Collection, London.

177. Adam Frans van der Meulen, 1632-1690, French. An Army Encamped Beside a Wide River, date unknown. Drawn in pen, washed, 35 x 28.7 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Baroque.