14TH - 15TH CENTURIES

From the first third of the 14th century to the middle of the 15th century, the Hundred Years‘ War carried social tension and instability around Europe and greatly shaped this period. Despite the conflict, influential families drove the development of the ‘international‘ forward. This exchange between various courts pushed the formation of the artist movement of soft styles in the late Gothic. The artists travelled from court to court and left behind their manner, style and technique. They all distinguished themseves through their efforts towards refinement and daintiness.

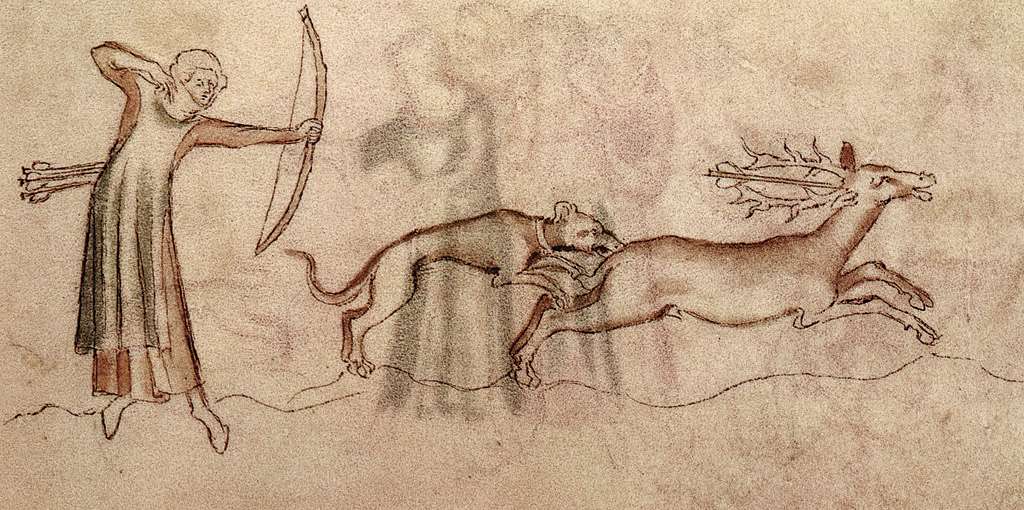

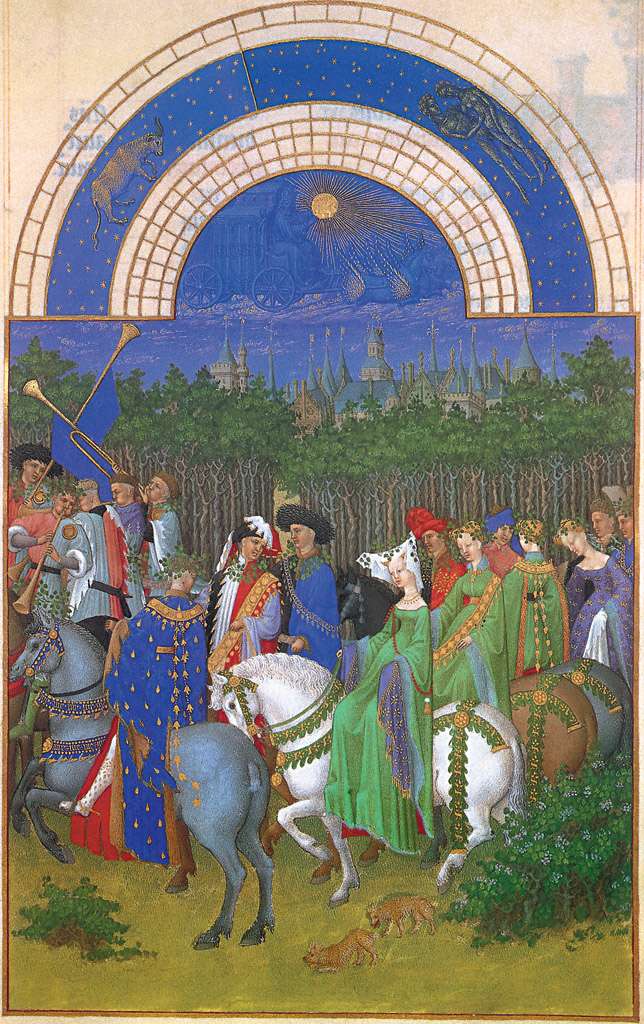

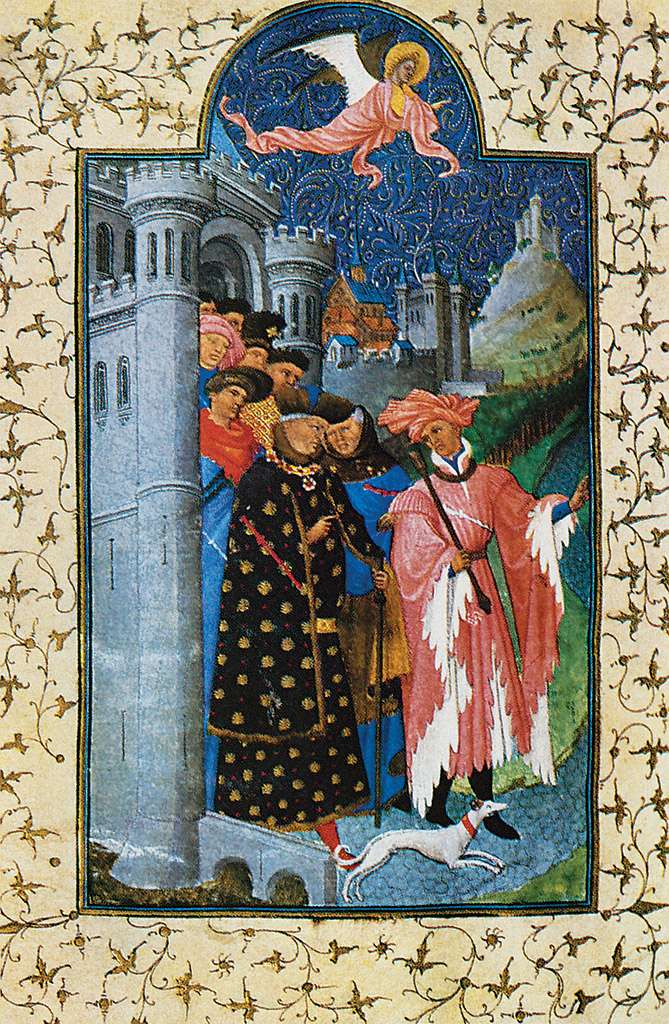

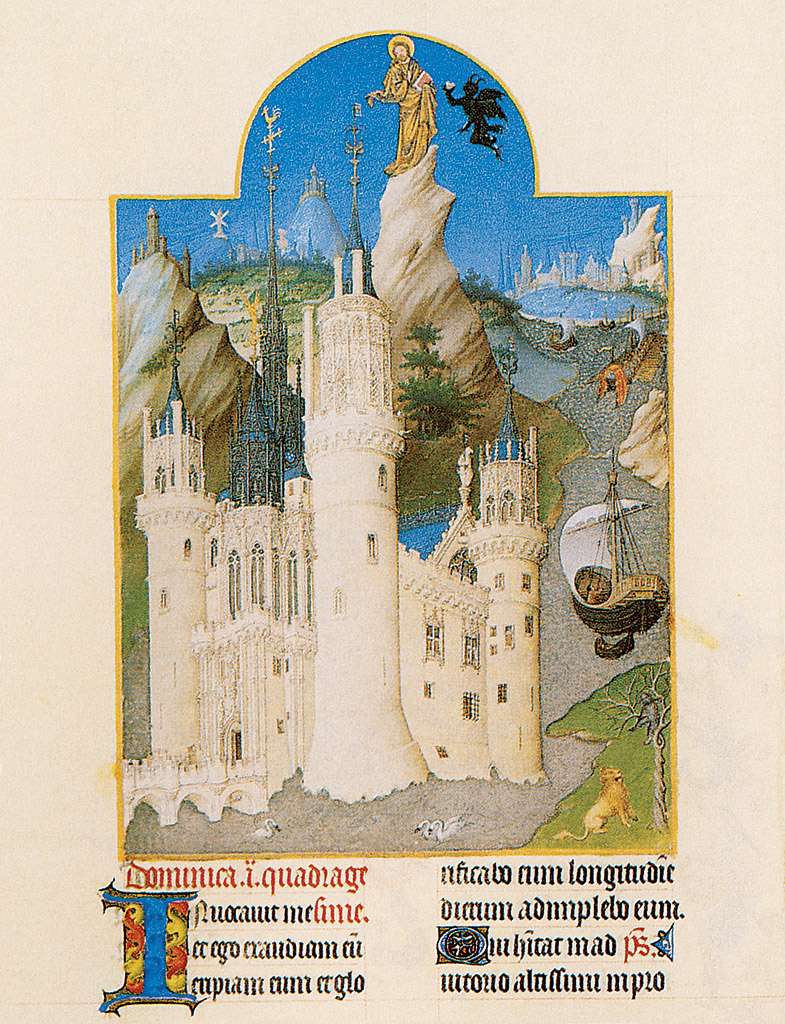

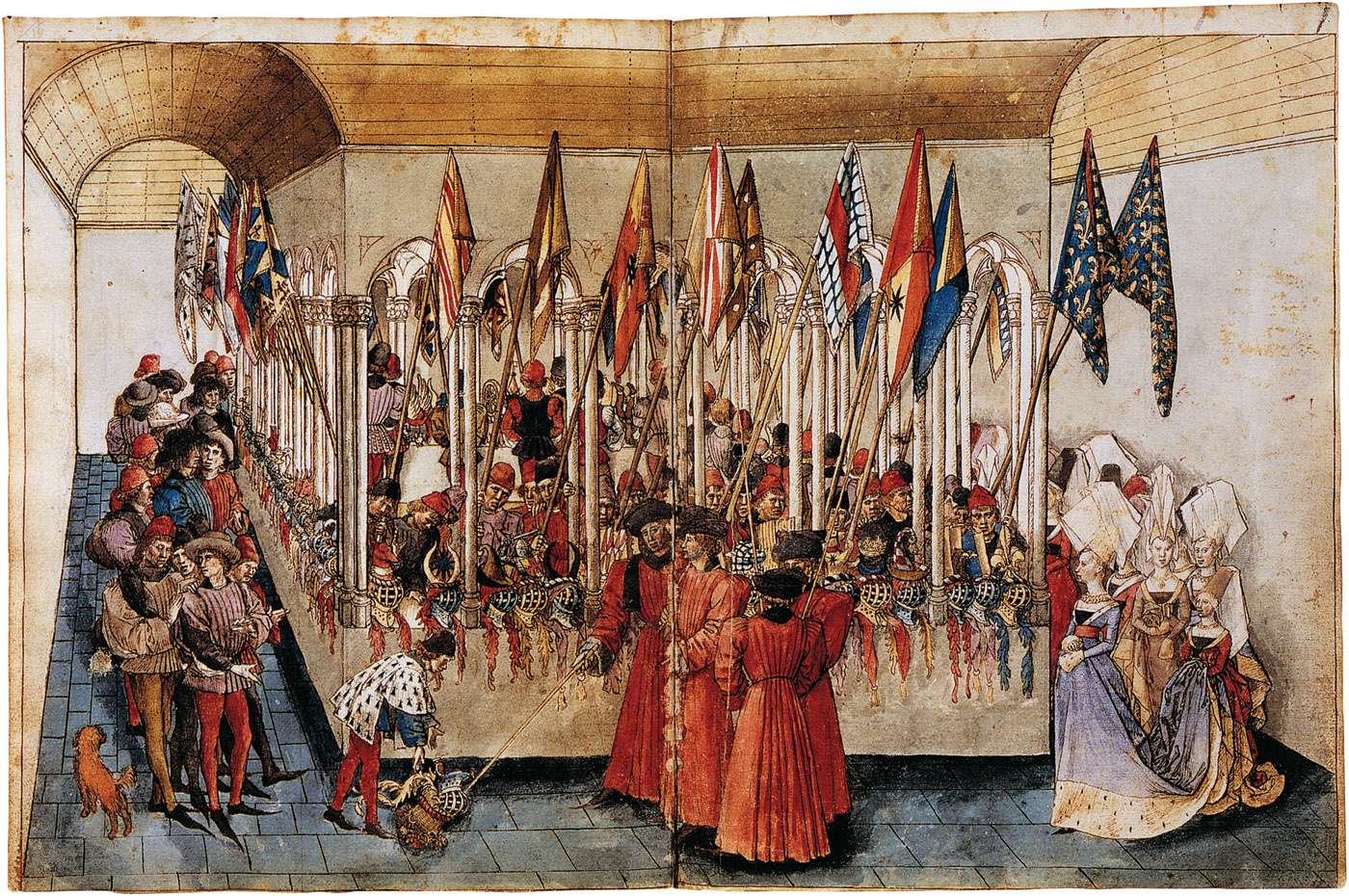

The illustration of manuscripts is one of the art forms that flourished in this era. As a symbol of such finesse, which was considered ideal at the time, they represented a significant step in the history of watercolour. The artists dissolved coloured ink in water, which was applied to vellum in delicate brushstrokes. If the more or less 1,320 existing illustrated drawings in Psalter of the Queen Mary (ill. 1 and ill. 6) are unrealistic, so are the miniatures of the hour books Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry from the Limbourg brothers (c. 1385-1416) almost overflowing with details. They are indeed not free from schematism, but testify to the honest desire of the artist to capture daily life. For example, May (ill. 7) presents the traditional cavalcade of 1 May; the numerous figures, the buildings in the background, and the astrological image piece are carefully produced over the actual illustration. This was also the first time that miniatures were produced in full page; thus, the genesis announced the autonomous works of watercolour painting. Later, Barthélemy d’Eyck (active 1444-1469) would finish the work of the Limbourg brothers on Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry before he went into the service of King René I. d’Anjou (1409-1480) and illustratate for him the Tournament Book (ill. 29). His miniatures are, with the help of the washing technique, accentuated ink drawings, which allowed the artist to play with the effect of light-dark: He got close to modern watercolour with the techniques that he applied.

During the 15th century, northern art received the characteristics of soft styles, whereby it, especially in regards to the artistic implementation of depicted objects, perfected nature and flowers. With his Study of Peonies (ill. 32), Martin Schongauer (1450/1453-1491) provided one of the first botanical studies. For this purpose, the plants were drawn from various angles in full bloom or in budding stage. He reached a subtle tone in which he applied the washing technique and the use of gouache in order to bring out the details of the application. With the help of watercolour technique, Schongauer became a great pioneer of botanical studies, which developed in the following century.

Meanwhile, in Italy entirely new issues arose. The Medici family played an important roll in the development of art; Cosimo the Elder (1389-1464) and later Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492) were important patrons who supported artists like Sandra Botticelli (1445-1510), Filippino Lippi (1457-1504), and Leonardo da Vanci (1452-1519). During that time, Florence became the capital of the early Renaissance. This time was punctuated by diverse innovations, especially in the field of art with the pioneer work in regards to principal perspective contributed by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446). This made it possible to create a great illusion in the two-dimensional painting, where an impression of three-dimentionality was produced – a veritable revolution.

New aspirations were formed with the birth of Humanism and also on an intellectual level. Italian artists, which brought as much interest to people as nature, celebrated the beauty of bodies, the grace of the lineaments and the harmony of form. Art emancipated itself: The time of applications of purely religious points of view was over. Now they sought to be a mirror of reality. In order to better be able to comprehend the nature which surrounded them, artists invented the method of sketching. This preparatory phase of works allowed the painters to test out and compare various viewpoints of the same objects. In this stage, some also used colour pigment, which they mixed with water, in order to elevate their work and get it closer to reality. Botticelli’s drawing Pallas Athene (ill. 27) illustrated the humanistic purpose of the artist by capturing the real movement of the body through the doubling of the head of a young girl.

As a result of the growing wealth, which the market entered, and the new intellectual alignment, art came to know an appreciation, not least in terms of materials which were available to it. During this time, artists began to find an aversion to the egg-based tempera technique and found preference in oil painting instead. This technique was used for hundreds of years, however, it initially established itself across the board in the 15th century, later in the north, and as a result, in the south as well. The oil painting had enormous success, and to this day, is the prefered method of painting. During this time, the technique of watercolour was still in its infancy. Its history had just began.

2. Pisanello (Antonio Pisano), c. 1395-1455, Italian. European Bee-Eater, Perched on a Flowering Stalk; Sketch of Bird’s Feet, date uknown. Watercolour, quill and brown ink, white lead, metalpoint, quill (for the flowered stem), 11.4 x 17.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Early Renaissance.

3. Pisanello (Antonio Pisano), c. 1395-1455, Italian. Two Studies of a Deer, in Profile and from the Left, date unknown. Metalpoint, the head of the deer on the left finished in watercolour, 20.3 x 25.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Early Renaissance.

4. Giovannino de’ Grassi, c. 1350-1389, Italian. Two Young Women Playing Music, 1380-1398. Quill, ink and watercolour on parchment, 26 x 19 cm. Civica Biblioteca Angelo Mai, Bergamo. International Gothic.

5. Giovannino de’ Grassi,c. 1350-1398, Italian. A Lion Eating a Deer, 1380-1398. Ink, traces of silver shades, white tempera and watercolour on parchment, 26 x 19 cm. Civica Biblioteca Angelo Mai, Bergamo. International Gothic.

6. Queen Mary Master, English. Hunting Scene from the Queen Mary Psalter, c. 1310-1320. Ink on parchment. British Library, London. Late Middle Ages.

7. Paul, Johan, and Herman Limbourg, c. 1385-1416, Dutch. May from the Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1410-1416. Manuscript illumination, 22.5 x 13.6 cm. Musée Condé, Chantilly. International Gothic.

8. Paul, Johan, and Herman Limbourg, c. 1385-1416, Dutch. Miniature Accompanying the Prayer Before Setting Out on a Journey, from the Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1410-1416. Manuscript illumination, 21.5 x 14.5 cm. Musée Condé, Chantilly. International Gothic.

9. Paul, Johan, and Herman Limbourg, c. 1385-1416, Dutch. The Temptation of Christ (showing Méhun-sur-Yèvre castle), from the Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1410-1416. Manuscript illumination, 29 x 21 cm. Musée Condé, Chantilly. International Gothic.

10. Paul, Johan, and Herman Limbourg, c. 1385-1416, Dutch. The Expulsion from Paradise, from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1410-1416. Manuscript illumination, 29 x 21 cm. Musée Condé, Chantilly. International Gothic.

LIMBOURG BROTHERS

(NIJMEGEN, C. 1380-1416)

Paul, Johan and Herman Limbourg were brothers whose family produced traditional coats of arms. After the death of their father, they lived with their uncle in Paris, the famous Jean Malouel, at the time a painter of French and Burgundian courts. After they went to apprentice for a goldsmith, they found work as book painters for Philipp II. In 1404, they were sent to the service of Jean de Valois, Duke of Berry. As an assignment, he gave them the book illustrations for the book of hours, Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry. The Limbourg brothers attained fame from this work. They comprised 158 miniatures on 206 pieces of vellum parchment, most likely produced within four and five years. The use of colour made it an especially exceptional work. The Limbourg brothers preferred precious colour pigment like lapis lazuli or vermillion. The book is especially famous for the calender miniatures portraying the courtly life of the Duke of Berry. It is hard to determine how the three brothers distributed the work between themselves. Did they work together on the same miniature or each on different ones? The Duke of Berry and the three brothers likely died in the same year, 1416, from the plague. Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, therefore, remained unfinished. It was Barthélemy d’Eyck who finished the work of the miniatures.

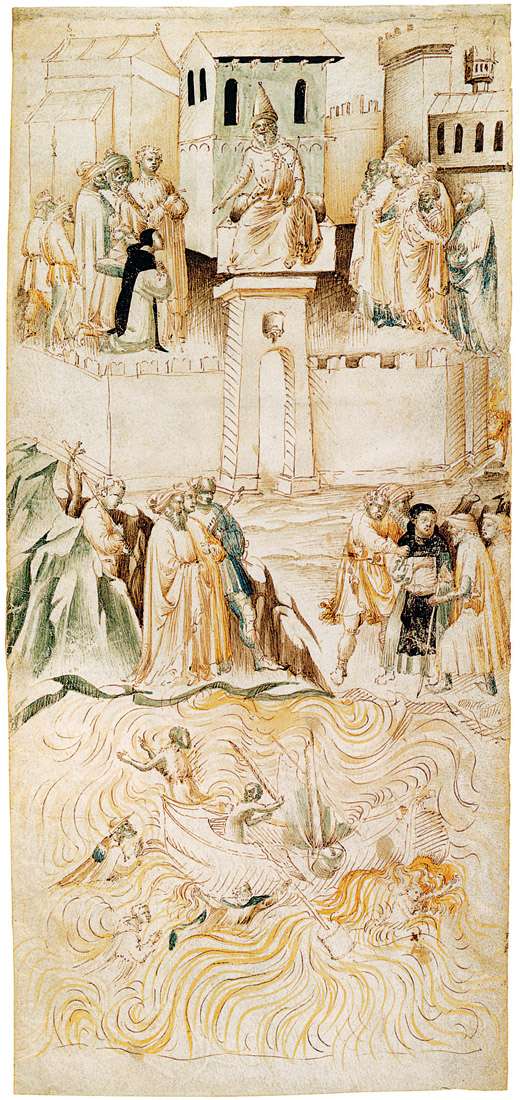

11. Anonymous, Italian. The Shipwreck of Brother Petrus, His Capture and His Audience before a Muslim Ruler, 1417. Quill and wash on parchment, 30.2 x 13.8 cm. Houghton Library, Havard University, Cambridge (Massachusetts). Late Gothic.

12. Anonymous, Italian. The Domican, Petrus de Croce, Encountering the Devil and Serpents, 1417. Quill and wash on parchment, 24.1 x 13.4 cm. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo. Late Gothic.

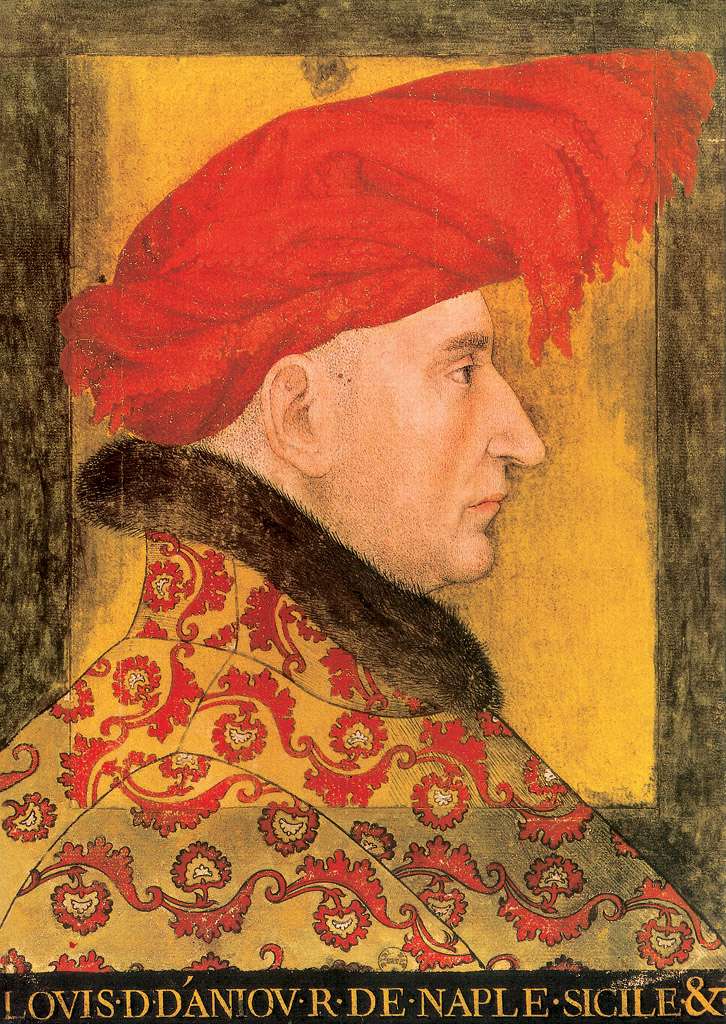

13. Barthélemy d’Eyck, 1440-1470, Flemish. Louis II of Naples, c. 1456-1465. Quill and watercolour drawing, 30.7 x 21.5 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Northern Rennaissance.

BARTHÉLEMY D’EYCK

(PRINCE-BISHOPRIC OF LIÈGE, ACTIVE 1440-1470)

There are few historic sources which allow for the reconstruction of the life of Barthélemy d’Eyck. Therefore, it is assumed that in the 1430s he received a painting education in the presence of brothers Jan and Hubert van Eyck. It is likely that he contributed some miniatures to the Très Belles Heures de Notre-Dame. Because of an encounter in 1435 with King René I. d’Anjou in Dijon, he became a court painter. René d’Anjou later financed more ateliers for him in his various residences. Originally from the Netherlands, his style was more similar to the old Dutch painters of Flanders. Barthélemy d’Eyck was also greatly influenced by the art of Robert Campins, who anticipated the Flemish Renaissance with his realistic style. The works of Barthélemy d’Eycks reveal a great mastery in the suggestions of spatiality. The painter excellently succeeded in portraying movement in his miniatures, which is impressively proven by the ink drawings that were drafted for René d’Anjou, Livre des Tournois, and elevated with Indian ink.

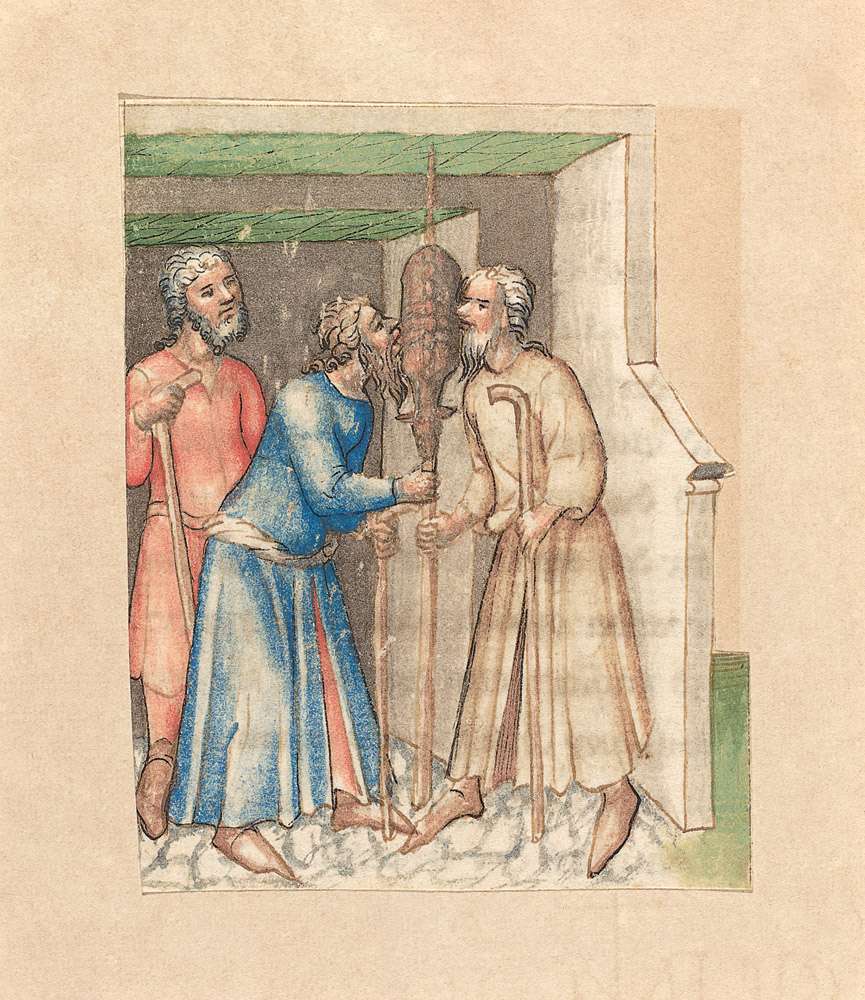

14. Anonymous, Austrian. Eating Sacrificial Lamb, c. 1420-1430. Pen and ink with watercolour, 10.5 x 8.5 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Late Gothic.

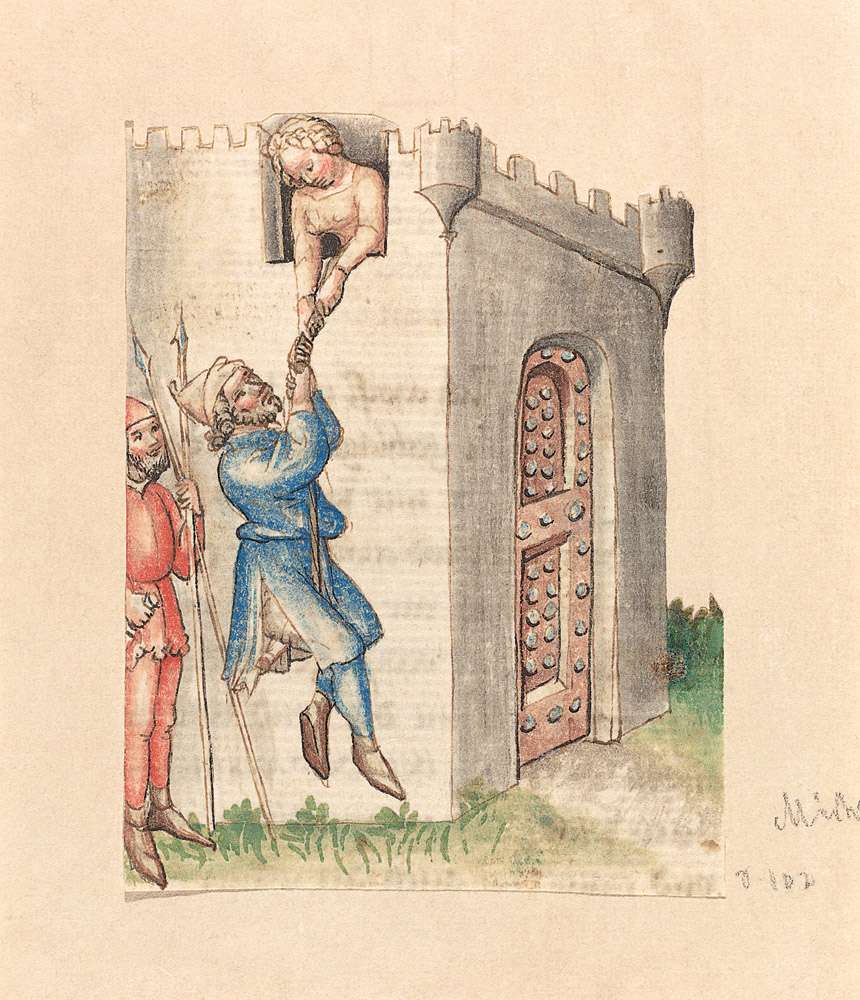

15. Anonymous, Austrian. Woman Suspending Man from Tower, c. 1420-1430. Pen and ink with watercolour, 10.8 x 8.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Late Gothic.

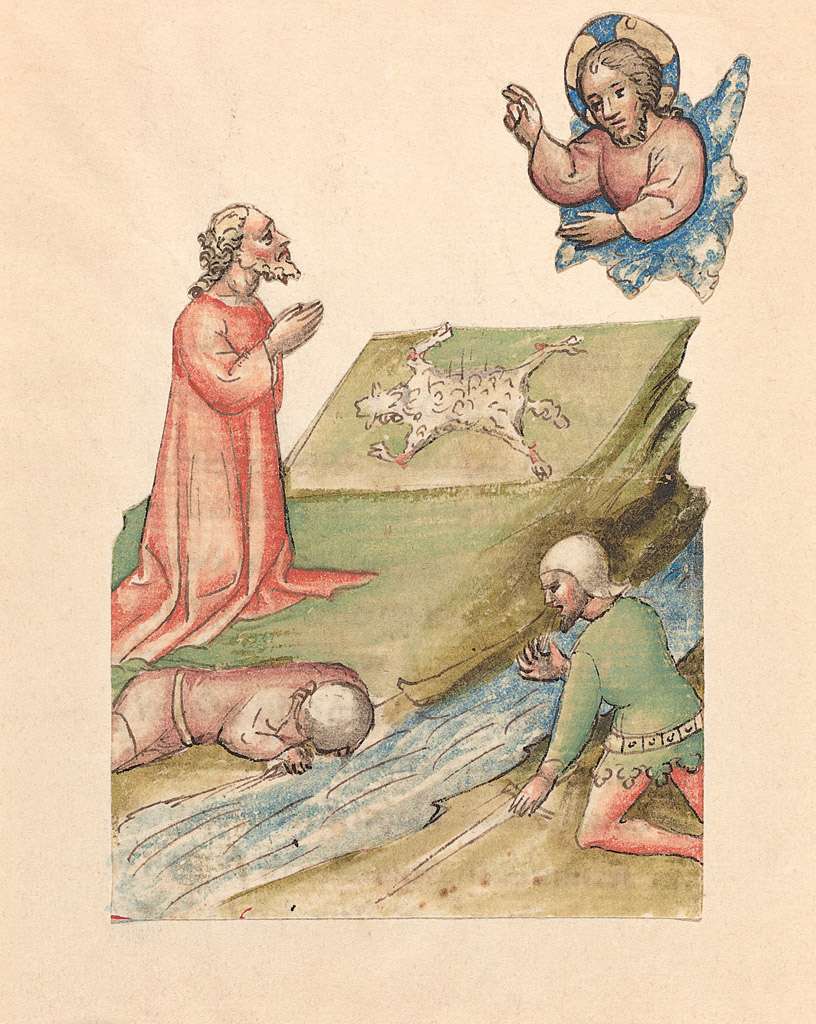

16. Anonymous, Austrian. God the Father, Three Figures and Sacrificed Lamb, c. 1420-1430. Pen and wash on parchment, 12.7 x 8.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Late Gothic.

17. Anonymous, Austrian. A Stoning, c. 1420-1430. Pen and ink with watercolour, 7.5 x 9.2 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Late Gothic.

18. Anonymous, Austrian. Seated Old Man and Standing Soldier, c. 1420-1430. Pen and ink with watercolour, 6.8 x 8.5 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Late Gothic.

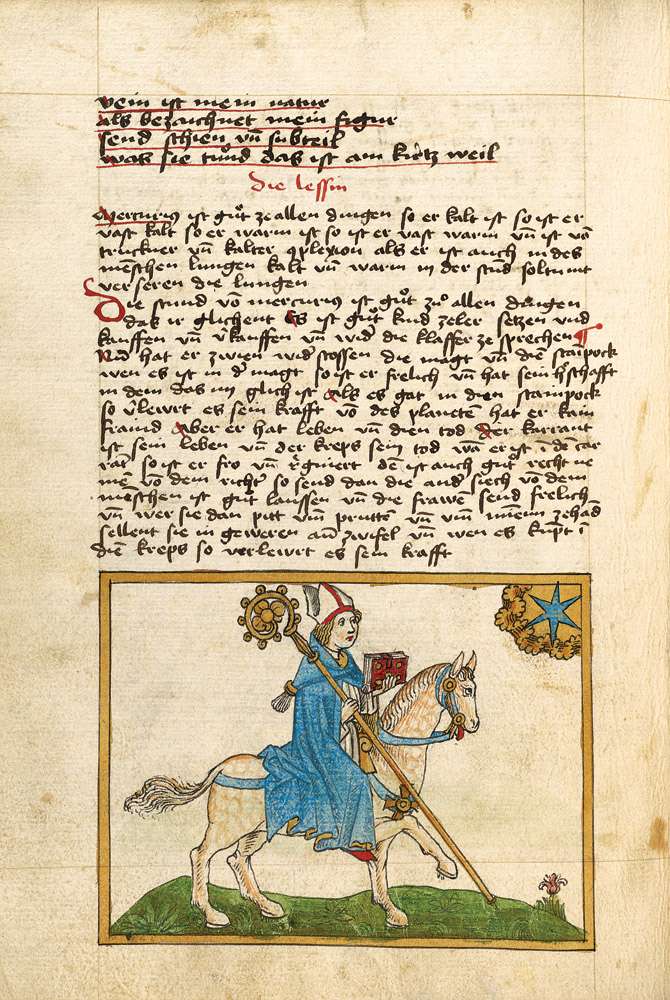

19. Anonymous, German. The Planet Jupiter Represented as a Bishop on Horseback, after 1464. Watercolour and ink on paper, 30.6 x 22.1 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

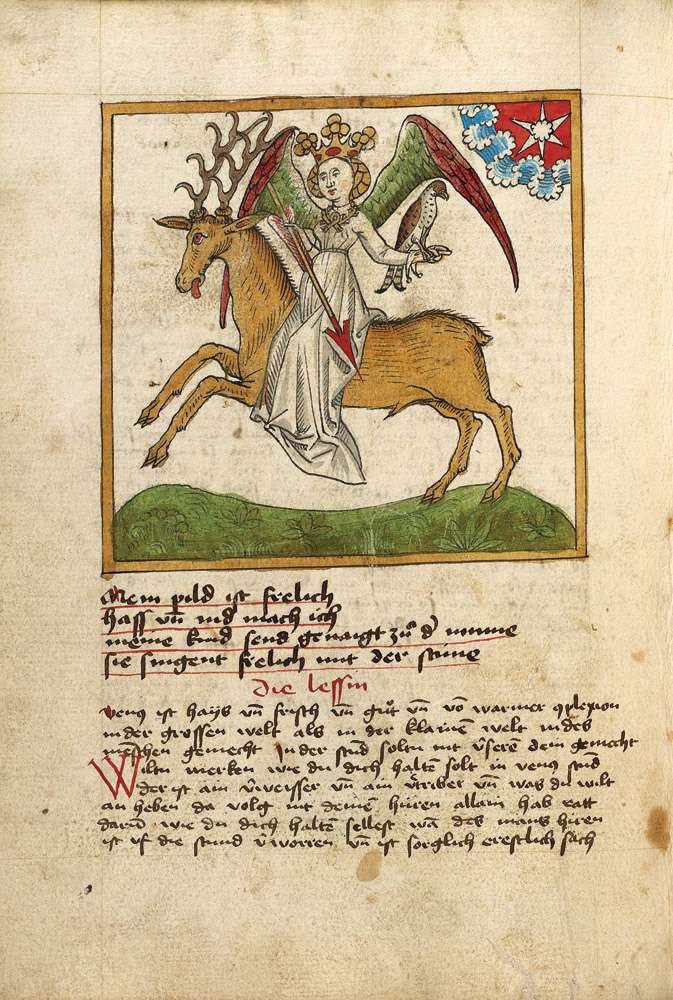

20. Anonymous, German. Venus Riding a Stag, after 1464. Watercolour and ink on paper, 30.6 x 22.1 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

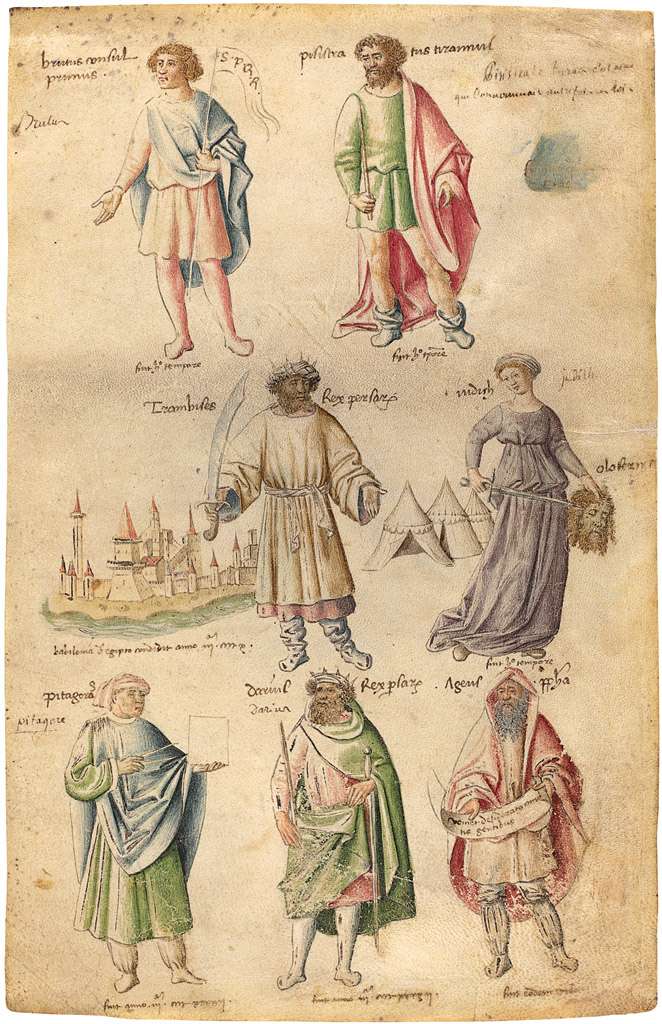

21. Barthélemy d’Eyck, active 1440-1470, Flemish. Seven Famous People from Ancient History, c. 1442. Quill and brown ink with watercolour and white on wove paper, 31.4 x 20.1 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Northern Renaissance.

22. Barthélemy d’Eyck, active 1440-1470, Flemish. Famous Men and Women from Classical and Biblical Antiquity, 1450’s. Quill and brown ink, brush and watercolour of various hues, traces of gold paint, 31 x 20 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Northern Renaissance.

23. Pisanello (Antonio Pisano), c. 1395-1455, Italian. A Gentleman and a Lady in Court Clothes, c. 1433-1438. Silverpoint and watercolour, 27.2 x 19.3 cm. Musée Condé, Chantilly. Early Renaissance.

PISANELLO

(ANTONIO DI PUCCIO PISANO)

(PISA, C. 1395 – ROME C. 1455)

Pisanello, and thus also his artist name, ‘The Little Pisan’, originally came from Pisa. His art career, however, got its beginning in Verona. He traveled extensively throughout Italy to Venice, Mantua, Rome, Milan, and Naples, where he worked on various frescos, including those of the Doge’s Palace and the Lateran Basilica. The Portrait of a Princess, which hangs in the Louvre, is surely Pisanello’s most famous work.

It shows the princess in profile and in three quarters against a background of flowers and insects, which is presented with the attention to detail also found in his miniatures. This painting is evidence of his effort to reach a profound knowledge of foot art. Pisanello also produced a great number of watercolour drawings on parchment paper. Marcel Proust payed homage to him in In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, “Gradually, as the year advanced, the image that I saw in the window changed. At first it was very bright and dark only when there was bad weather: then standing in turquoise glass – and swollen with its round waves – the ocean, and bordered in the iron frame of my window like in the lead of the old church windows, occupied in the deeply cut, rocky edge of the bay with frayed triangles, whose sides foam in polylines, so fine, like a feather or down, when Pisanello draws it.”

24. Filippo Lippi, 1406-1469, Italian. Preparatory study for Virgin and Child Attended by Angels, c. 1465. Pen and brown ink, brush and brown wash, highlighted with white gouache, 33 x 26 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Early Renaissance.

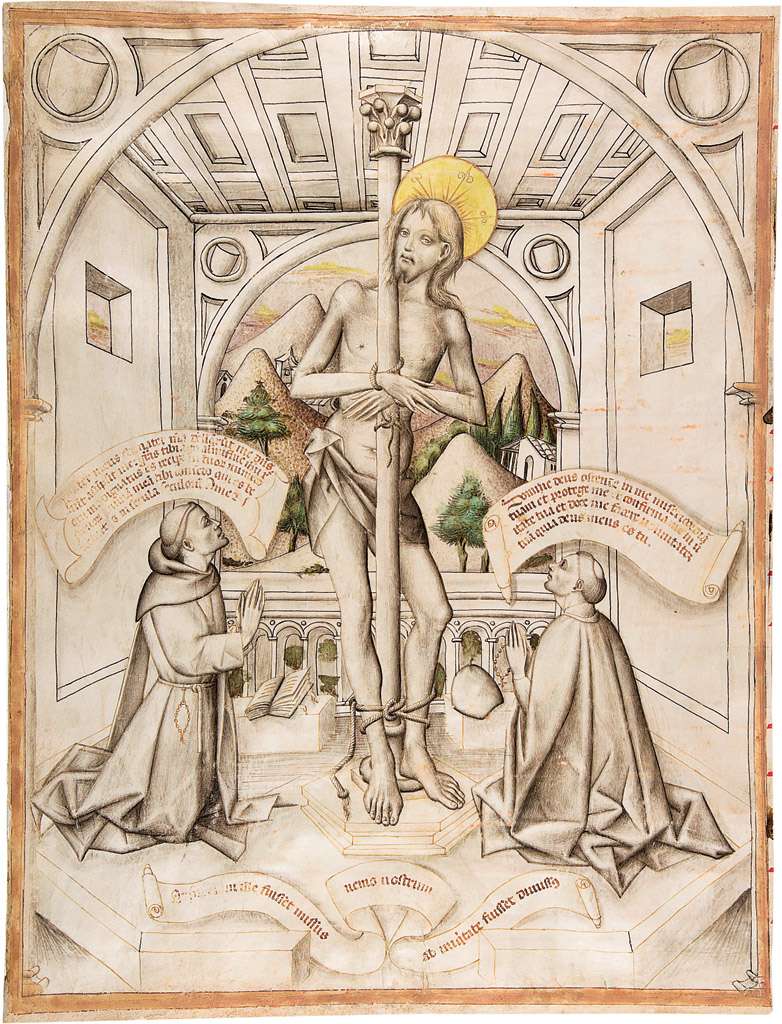

25. Delli Brothers, active 1430-1460, Italian. Christ at the Column, c. 1440-1470. Pen with brown and black carbon ink, brush with gray wash, watercolour, and gouache on parchment, inscriptions in brown ink of a different type, 40.3 x 30.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Early Renaissance.

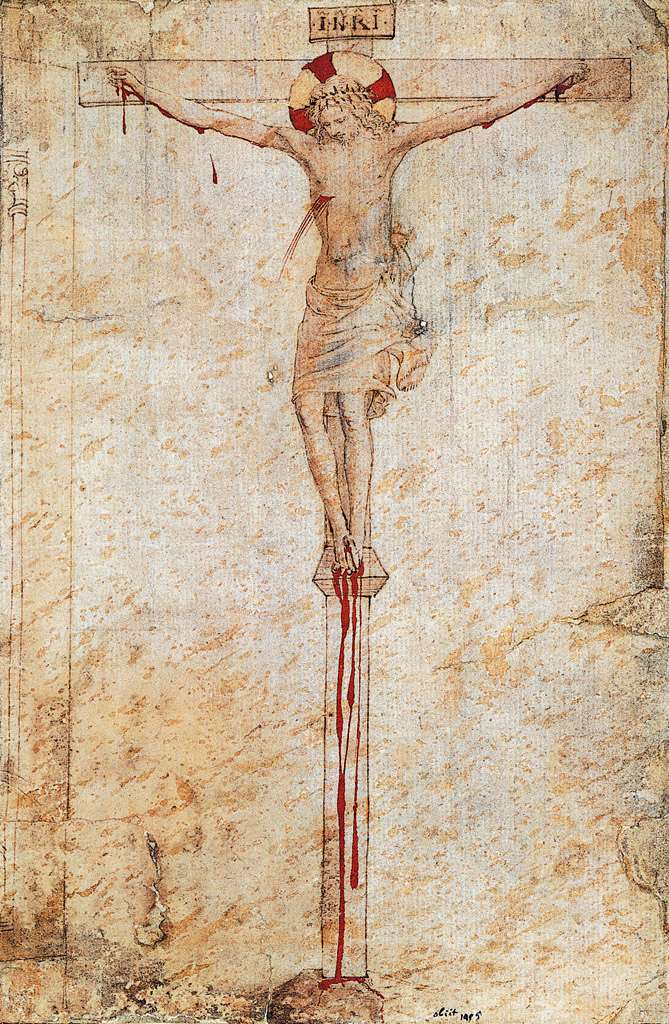

26. Fra Angelico (Guido di Pietro), c. 1395-1455, Italian. Christ on the Cross, c. 1430. Quill and brown ink, with red and yellow wash on parchment, 29.3 x 19 cm. Grafische Sammlung, Albertina, Vienna. Early Renaissance.

27. Sandro Botticelli, 1445-1510, Italian. Pallas, c. 1475. Black pencil, pen, wash, ceruse, parts a light brown watercolour, white paper partially tinted pink, 22.2 x 13.9 cm. Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Florence. Rennaissance.

28. Sandro Botticelli, 1445-1510, Italian. Saint-Baptiste, c. 1485-1490. Quill, parts a light brown watercolour, ceruse, white paper yellowed and partially tinted pink, fully glued, 35.9 x 15.6 cm. Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Florence. Renaissance.

29. Barthélemy d’Eyck, active 1440-1470, Flemish. The Book of Tournaments of René d’Anjou, c. 1460. Quill and watercolour, 38.5 x 60 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Early Renaissance.

30. Attributed to Master of Gouda, Dutch. Christ and His Disciples in the House of the Pharisee Refuse the Ritual Washing of Hands, 1482-1484. Watercolour on paper, 9.6 x 13 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

31. Attributed to Master of Antwerp, Dutch. Christ in the Pharisee’s House, 1485-1491. Watercolour on paper, 9.3 x 12.8 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

32. Martin Schongauer, 1450/1453-1491, German. Study of Peonies, c. 1472-1473. Gouache and watercolour, 25.7 x 33 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Northern Renaissance.

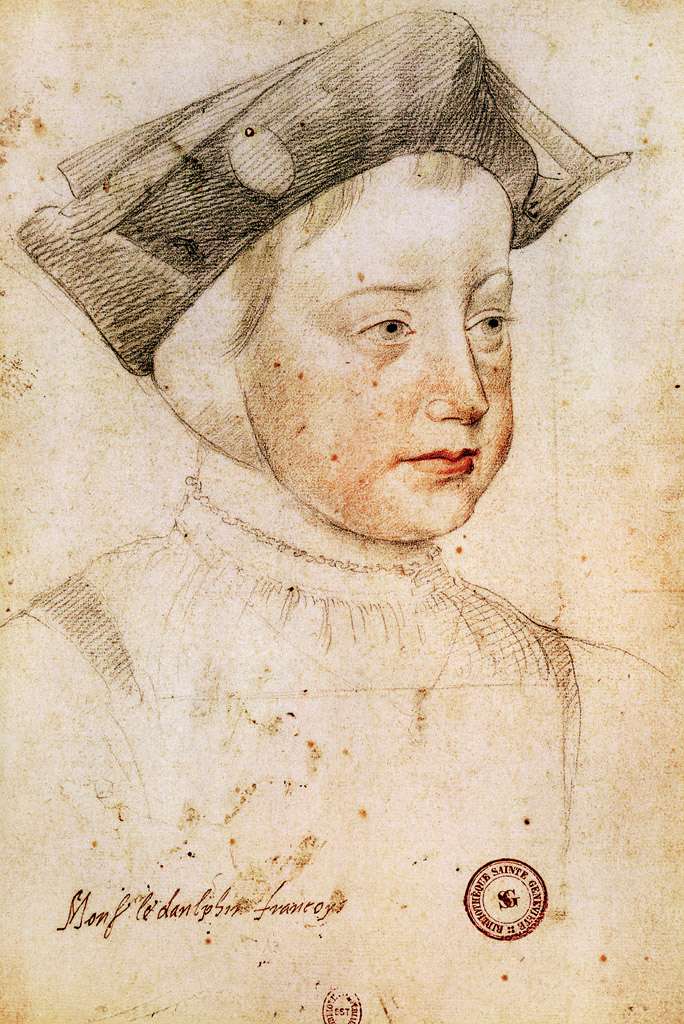

33. Jean Clouet, c. 1475/1485-1540, French. The Dauphin François, date unknown. Pencil, red chalk and touches of watercolour. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Renaissance.

34. Fra Bartolommeo, 1475-1517, Italian. The Temptation of St Anthony, c. 1499. Quill and ink with brown wash and white heightening, on paper washed yellow, 23.3 x 16.6 cm. The Royal Collection, London. Mannerism.

35. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519, Italian. A Lily (Lilium Candidum), c. 1475. Pen, ink, and ochre wash with white heightening over black chalk, 31.4 x 17.7 cm. The Royal Collection, London. High Renaissance.

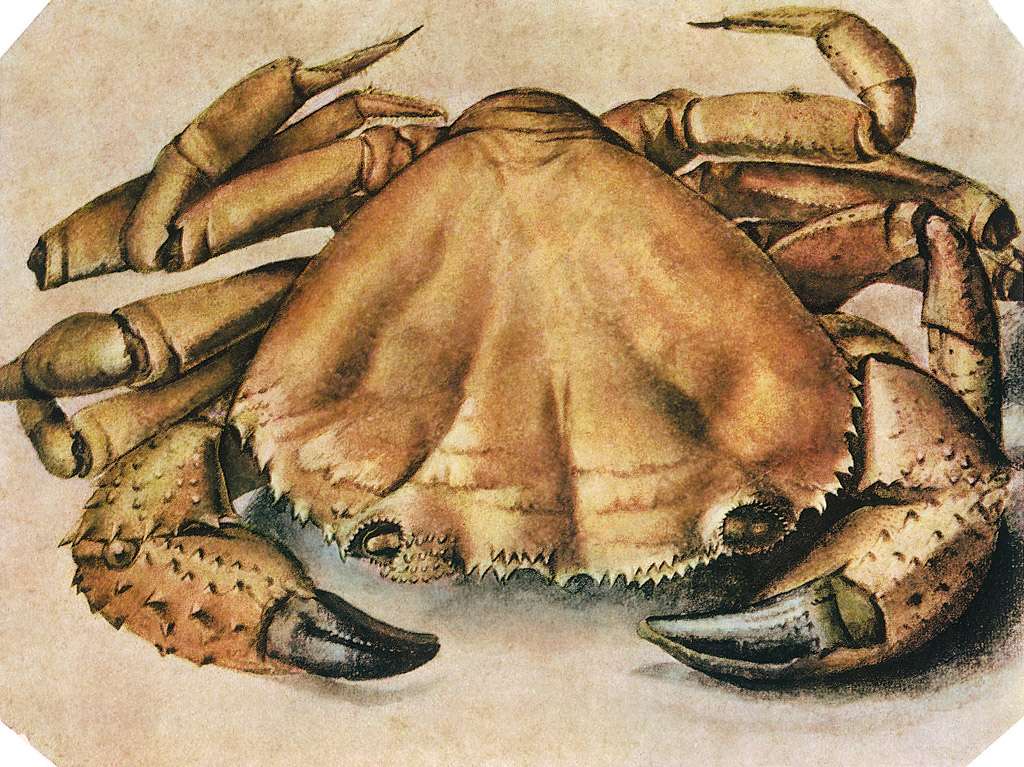

36. Albrecht Dürer, 1471-1528, German. Sea Crab, 1495. Watercolour and gouache, 26.3 x 35.5 cm. Museum Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Northern Renaissance.

ALBRECHT DÜRER

(NUREMBERG, 1471-1528)

Dürer is one of the greatest of the German artists and the most representative of the German mind. He, like Leonardo, was a man of striking physical attractiveness, great charm of manner and conversation, and mental accomplishment, being well grounded in the sciences and mathematics of the day. His skill in draughtsmanship was extraordinary; Dürer is even more celebrated for his engravings on wood and copper than for his paintings. With both, the skill of his hand was at the service of the most minute observation and analytical research into the character and structure of form. Dürer, however, had not the feeling for abstract beauty and ideal grace that Leonardo possessed, but instead a profound earnestness, a closer interest in humanity, and a more dramatic invention. Dürer was a great admirer of Martin Luther, and in his own work, is the equivalent of what was mighty in the Reformer. It is very serious and sincere, very human, and it addressed the hearts and understanding of the masses. Nuremberg, his hometown, had become a great centre of printing and the chief distributor of books throughout Europe. Consequently, the art of engraving upon wood and copper, which may be called the pictorial branch of printing, was much encouraged. Dürer took full advantage of this opportunity.

The Renaissance in Germany was more a moral and intellectual movement than an artistic one, partly due to northern conditions. The feeling for ideal grace and beauty is fostered by the study of the human form, and this had been flourishing predominantly in southern Europe. Albrecht Dürer, though, had a genius too powerful to be conquered. He remained profoundly Germanic in his stormy penchant for drama, as was his contemporary Mathias Grünewald a fantastic visionary and rebel against all Italian seductions. Dürer, in spite of all his tense energy, dominated conflicting passions by a sovereign and speculative intelligence comparable with that of Leonardo. He, too, was on the border of two worlds, that of the Gothic age and that of the Modern Era, and on the border of two arts, being an engraver and draughtsman rather than a painter.

37. Francesco di Giorgio Martini, 1439-1501, Italian. Design for a Wall Monument, c. 1490. Quill and brown ink, brush and brown wash, blue gouache, on vellum, 18.4 x 18.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Renaissance.

38. Attributed to the Workshop of Master LCz, active 1480-1505, German. View of a Walled City in a River Landscape, c. 1485. Brown ink, coloured washes, gouache with black chalk underdrawing, 7.3 x 13.5 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

39. Albrecht Dürer, 1471-1528, German. View of Trento, c. 1494. Watercolour and gouache, 23.8 x 35.6 cm. Kunsthalle, Bremen. Northern Renaissance.

40. Albrecht Dürer, 1471-1528, German. Courtyard of the Castle in Innsbruck, c. 1496-1497. Watercolour and gouache, 36.8 x 26.9 cm. Grafische Sammlung, Albertina, Vienna. Northern Renaissance.