The Artist’s Studio, c. 1665. Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

CHAPTER I

MAPS AND EXPLORING

THE PORTOLANI: OLD NAUTICAL SEA-CHARTS

Maps, even those dating from centuries ago, influence our daily lives. They are one of the things that are part of our daily environment. Throughout history, besides its utilitarian function, every single map symbolises the period of time in which it was created. We are often reminded of the romance of antique maritime maps as we see them displayed in museums, or reproductions of them framed on the walls of private houses or institutions.

In a Vermeer painting a map may be seen telling a story-within-a-story (see illustration). In plays and films maps typically set the period. In fiction they may be called on to remind the reader of a world beyond the story’s setting. In Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, for example:

Had you followed Captain Ahab down into his cabin… you would have seen him go to a locker in the transom, and bringing out a large wrinkled roll of yellowish sea charts, spread them before him on his screwed-down table. Then seating himself before it, you would have seen him intently study the various lines and shading which there met his eye; and with slow but steady pencil trace additional courses over spaces that before were blank. At intervals, he would refer to piles of old logbooks beside him, wherein were set down the seasons and places in which, on various former voyages of various ships, Sperm Whales had been captured or seen.[1]

A map indicates not only the location of places, it can also help us see the world as did the people of its day. Each map is therefore a priceless snapshot in the on-going album of humankind. This is especially true with antique maps, by which we can see the world through the eyes of our forebears.

While the map-maker’s vision might later prove to be inadequate, maybe even incorrect, the unique truth it expresses tells a story that might not be revealed in any other way (see illustration).

It may well be said that each map-maker effectively traveled in his mind vicariously not only to the envisioned places but also to the future. Each was sure, along with the aging Pimen in the play Boris Godunov, that

A day will come when some laborious monk will bring to light my zealous, nameless toil, kindle, as I, his lamp, and from the parchment shaking the dust of ages, will transcribe my chronicles.[2]

One such laborious monk was the fifteenth-century mapmaker Fra Mauro. He was certainly responsible for bringing to light the work of several other map-makers. By doing so he helped make the transition from the Dark Ages to the beginning of the modern era (c. 1450).

Mauro was part of the the generation that was at work during the very focus of these significant times, over thirty years before the famous voyage of Christopher Columbus to the New World in 1492.

BREAKING WITH TRADITIONAL CHURCH MAPPING

Mauro probably went largely unnoticed in his monastery on an island within the Laguna Veneta (the lagoon that surrounds Venice). But his new map was destined to demand attention. It was large and round – which was unusual – almost 2 metres (6 feet) in diameter, yet still very definitely a map and not a global representation. It also included exceptional detail.

For the Asian part of the map Mauro took his data from the writings of Marco Polo. The rest was based on Ptolemy or his own contemporary sea-faring charts.

Mauro’s extraordinary work was completed in 1459. That was the time when the plainchant sung in his monastery – like the plainchant sung in many contemporary monasteries – might well have been changing to the more harmonic presentations of such innovating musicians as Guillaume Dufay (c.1400–1474).

Soon polyphonic masses began to anticipate the elaborate styles of the High Renaissance of 1500. In that innovative environment, Mauro may have wondered that if the singing of even the sacred texts of the liturgy were being freed of their over-simplicity, whether the Church’s representations of the Earth might likewise be given a new and meaningful dimension.

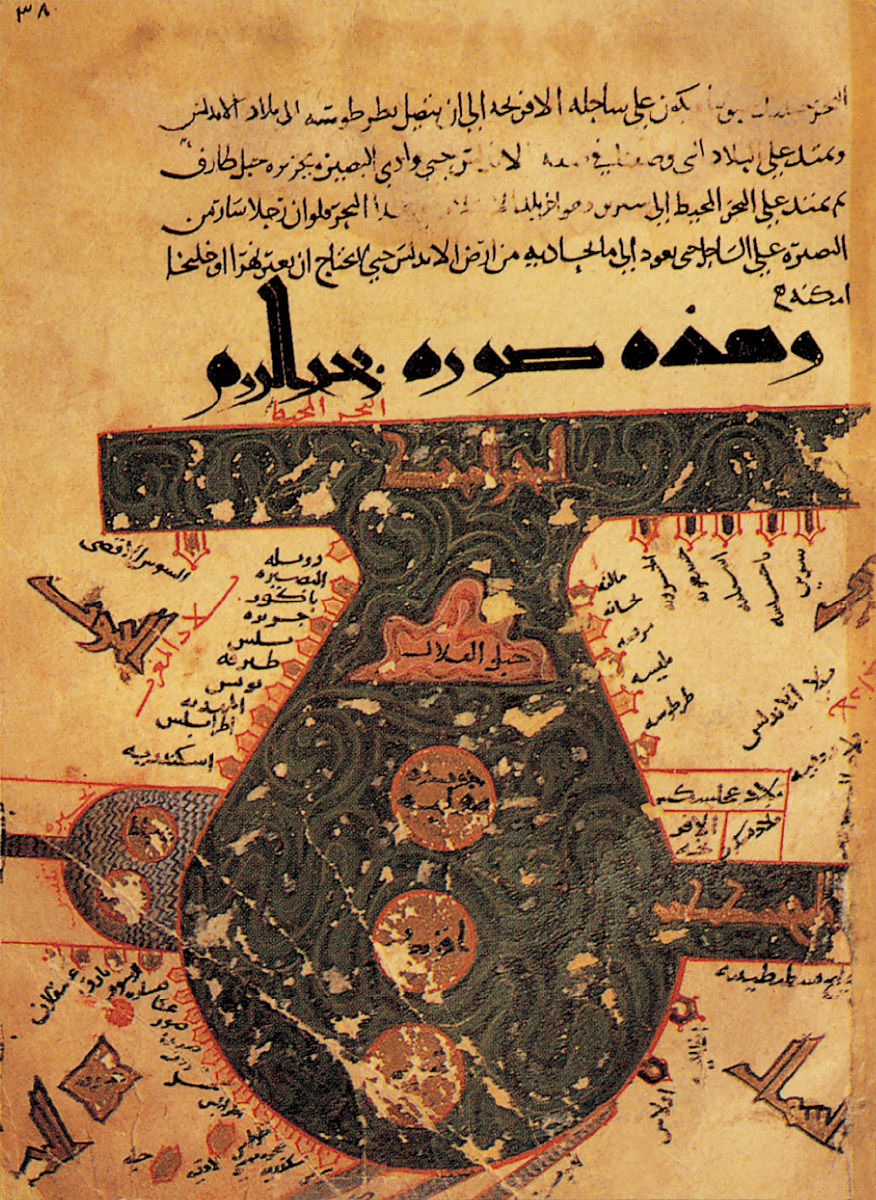

Mauro’s map did just that. By orienting his map to the south, rather than to the east, he broke with the Church’s tradition. He no longer showed Jerusalem as the center of the world (see illustration). Cartographer Alan G. Hodgkiss observes that ‘Indeed, Fra Mauro’s map can be said to mark the end of theologically-based map-making and the beginning of an era of scientific cartography.’[3]

Only sixty years after Mauro’s map was completed, Martin Luther stood his ground against Rome. And in turn that was seventy years before Copernicus published his Revolution of the Heavenly Bodies.

More than a century and a half later Galileo would confront the Church with the shattering news that the Earth was not the center of the universe.

This was a restless time for the Roman Catholic Church that liked to retain control and preserve tradition. Also in transition was the Earth itself, as after all its surface was being “discovered”. Its face was also becoming more clearly defined with each new exploration and subsequent map revision.

Just twenty years before Mauro’s map – as if anticipating the need to get such forth-coming information to the world – Gutenberg (1400–1468) developed his revolutionary printing press. The first printed map in 1477 followed the first printed Bible in 1440. Both were documents that would support, in very distinct ways, the emergence of international humanism. As if to link early Church teaching to the Age of Exploration, Mauro’s large circular map was completed at about the same time that elsewhere Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was born. Also born at about that time were the future navigators John Cabot (1451–1498) and Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), and the future explorer Vasco da Gama (1460–1524).

Mauro could not have foreseen that these young men would in a few years be the great explorers who would indeed bring to light the ‘zealous, nameless toil’ of his and other pioneering map-makers.

Ten years after Mauro came to the end of his work, Machiavelli (1469–1527) was born: it was he who would eventually encourage the kind of creative effort in art and politics that Mauro and other innovators prefigured. His was the individualism soon to be personified in the great explorers.

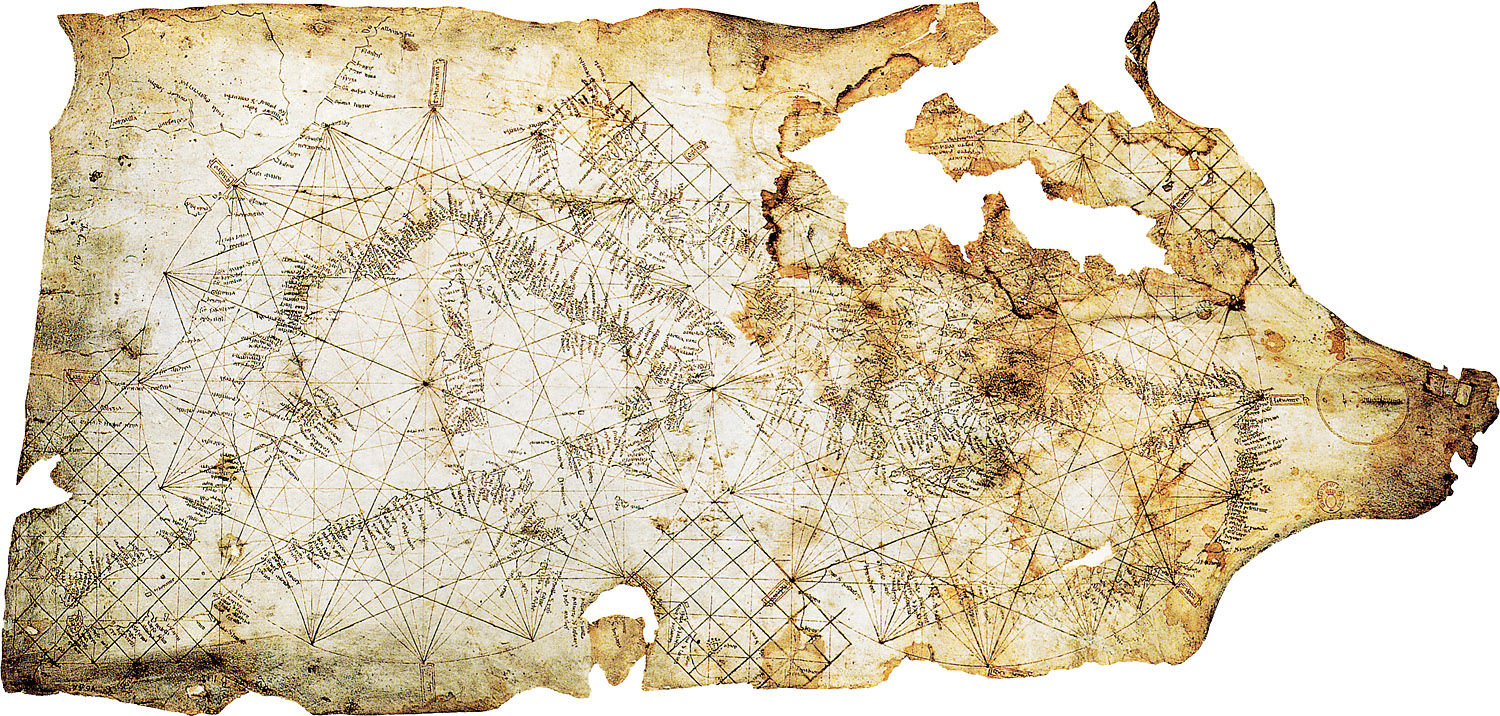

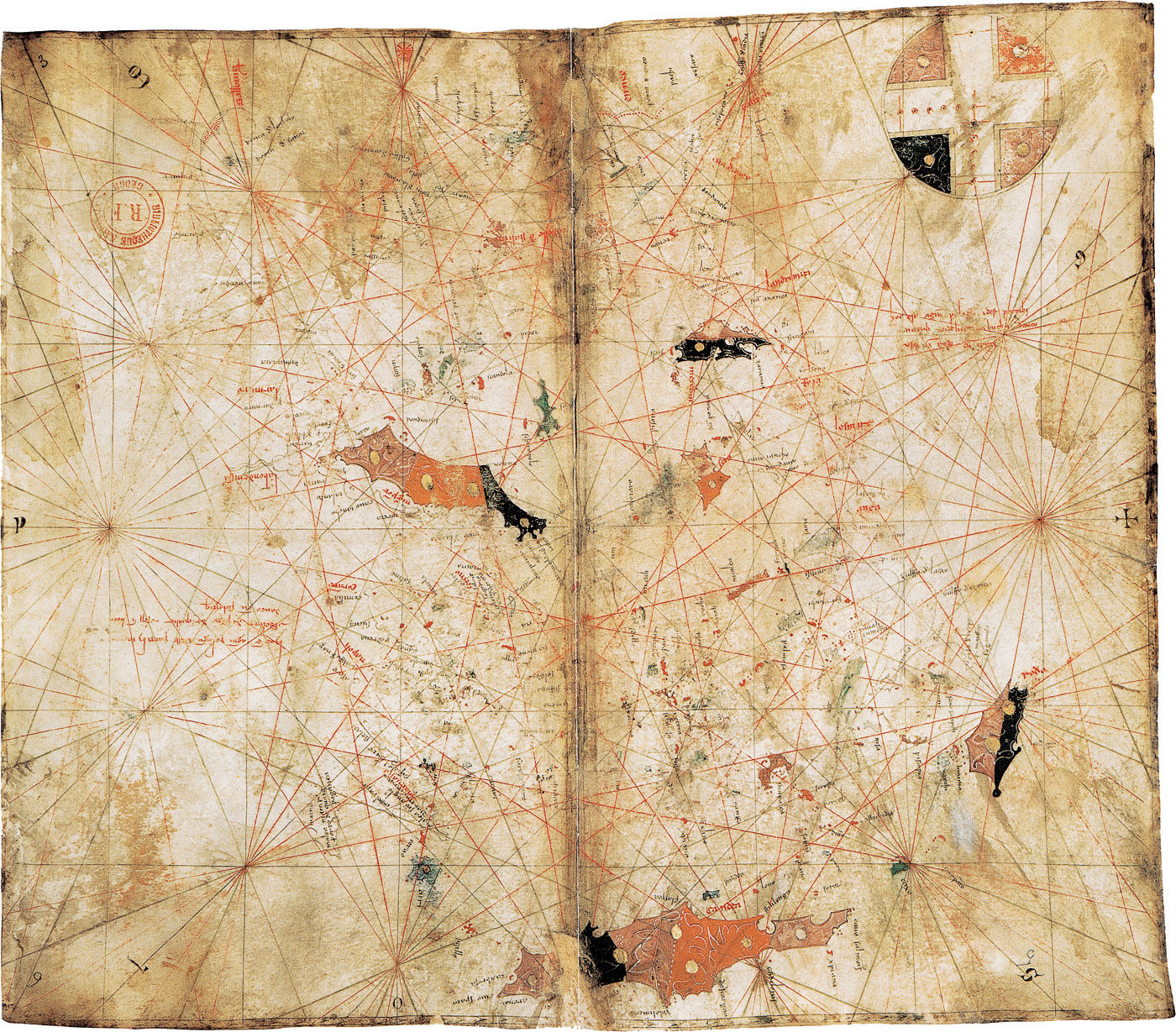

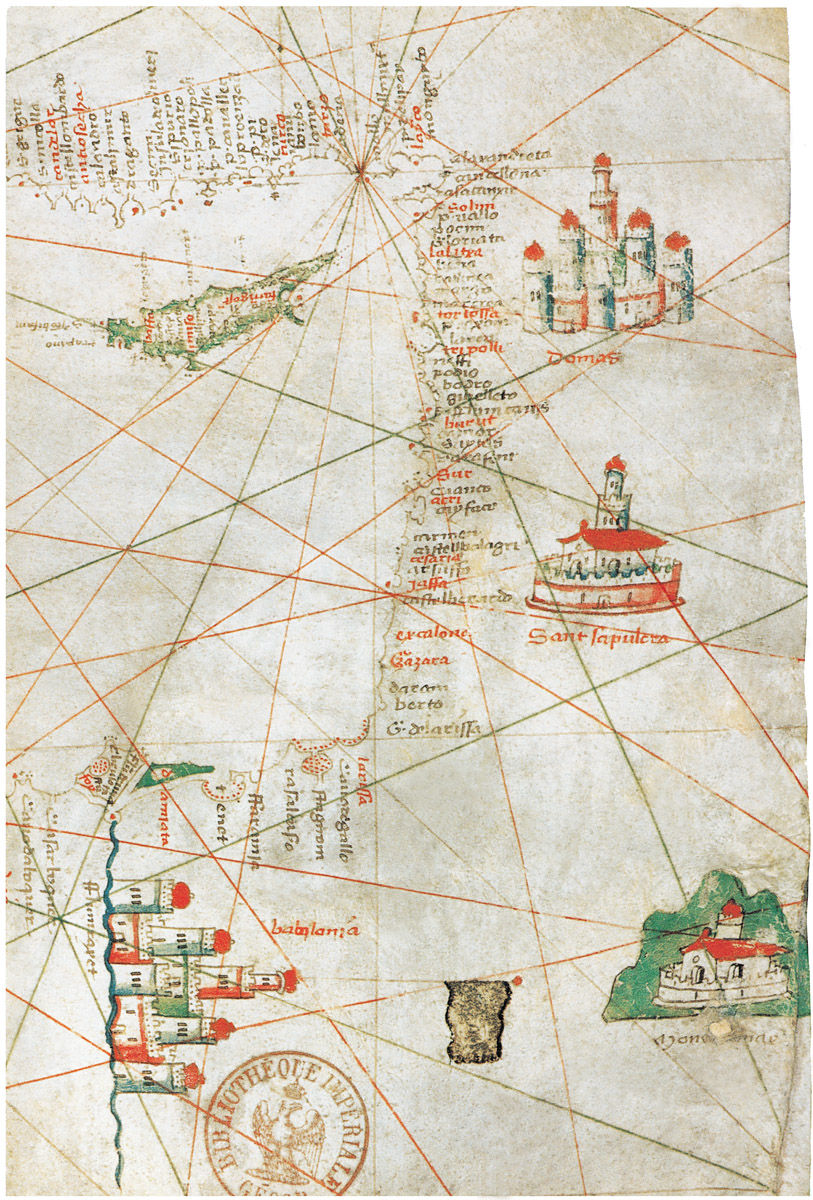

The Pisana Map, 1290. Unknown artist. Parchment, 50 x 105 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 1)

Arab Map Featuring Arabia as the Centre of the World, 10th century. Al-Istakhri. National Library, Cairo.

World Map, after 1262. In Psalter Map Manuscript, London, Ms-Add 28681. The British Library, London.

FROM ICE TO IRON: PREHISTORY TO 300 B.C.

Before launching into the choppy sea of knowledge that is the on-going discovery of our planet, let us briefly apply the theme of exploration first to the historical origins of humankind. The first thing to note is that in many discplines scientists once thought the epoch in which our earliest ancestors appeared was the Pleistocene or Ice Age.

In the late 1960s it was determined that the Pleistocene epoch began ‘only’ about 1.8 million years ago. For at least a century prior to that it was thought that the ‘Ice Age’ began several million years earlier. The academic juries may be out – as they nearly always are about such things – on how more modern studies will yet change the majority opinion.

Enter Humankind

We know that it was during the Ice Age that the extinction of certain mammals began – but at the same time humankind first appeared some 500,000 years ago. Also, with remarkable speed and thoroughness humankind evidently migrated to the American continents, undoubtedly at times traveling one way or another by sea as well as by land.

Meanwhile, elsewhere on Earth other human cultures were evolving. As we skip forward 497 millennia – more or less – we see distinctive civilisations arise, such as prehistoric Greece in the Neolithic Age.

By the early Iron Age (c. 800 BC to c. 500 BC) migrations by the Celts extended the use of iron into central and western Europe. We might again presume that the transition involved some sea travel, if not yet trans-oceanic voyages. Iron would of course play a vital part in the making of tools, nails, and equipment needed to build the ships that would spread the more technically advanced civilisations around the world.

By the fifth and fourth centuries before Christ we see not only distinctive groups but also influential individuals, along with their works, who become known beyond their immediate circle of influence.

In Greece, for example, great leaders arose who would significantly influence all aspects of subsequent generations. Among the many great thinkers of the era were Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle.

A pupil of Aristotle was later to become one of history’s greatest military leaders, the king of Macedonia, Alexander III. Although he would live for only thirty-three years, he was one of the few kings – along with Herod, the Roman-appointed king of Judea at the time of the birth of Jesus – to be called ‘the Great’.

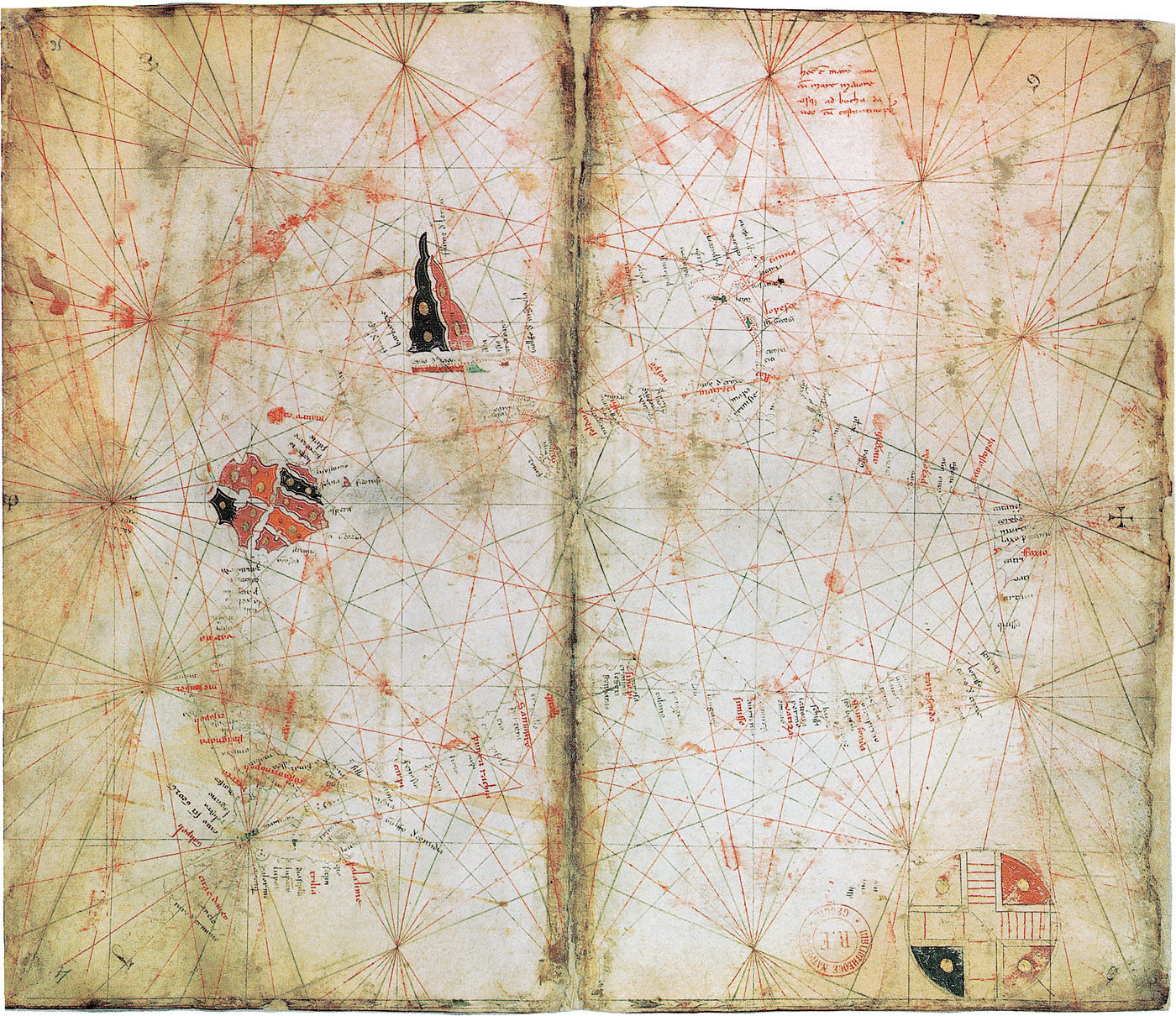

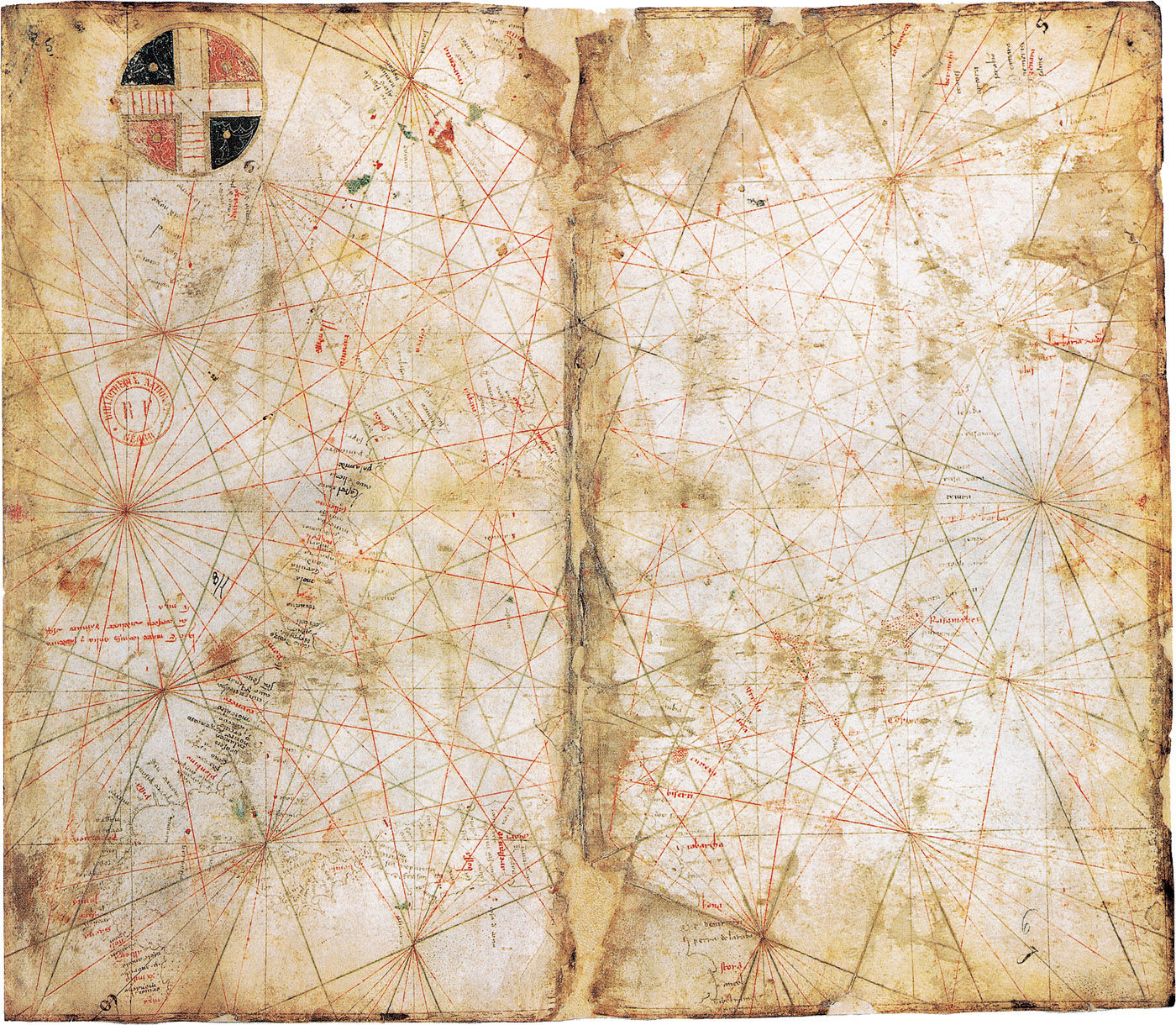

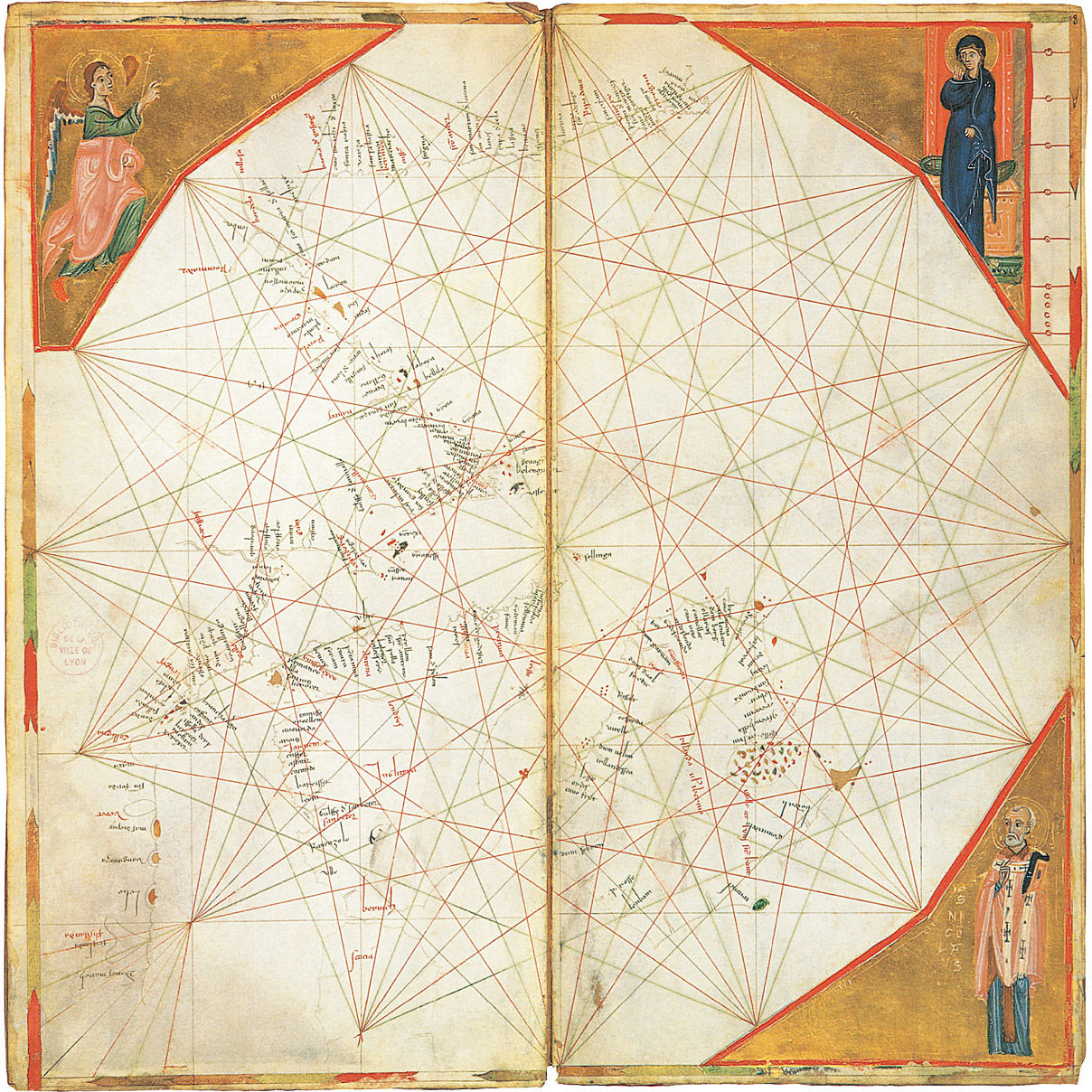

Atlas (Black Sea), 1313. Petrus Vesconte. Parchment, 48 x 40 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 2)

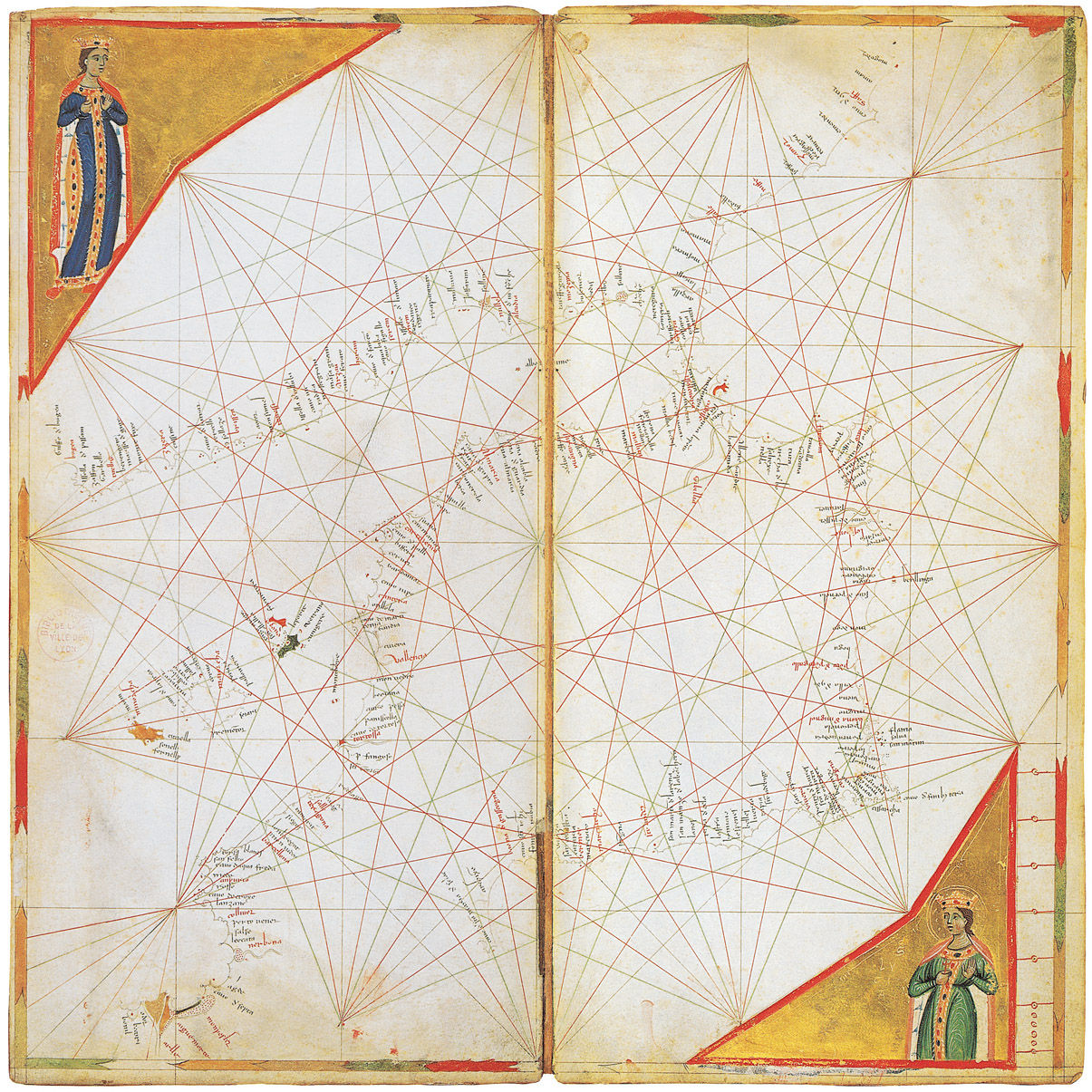

Atlas (Central Mediterranean Sea), 1313. Petrus Vesconte. Parchment, 48 x 40 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 3)

Atlas (Aegean Sea and Crete), 1313. Petrus Vesconte. Parchment, 48 x 40 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 4)

ALGEBRA MAKES THE WORLD SMALLER

For centuries, map-making, shipbuilding and navigation used only simple mathematics (whole numbers and fractions) for the calculations required.

The ancient Egyptians did not use symbols in their math, other than for real numbers; they did not use the abstract properties of numbers. However, problems such as we see in today’s introductory algebra textbooks were nonetheless posed as far back as 2000 years before Christ by the Babylonians and, indeed, by the Egyptians. The Greeks, through their use of geometry, discovered and used irrational numbers five centuries before Christ – irrational numbers are real numbers that have a nonrepeating decimal expansion.

While they surely used mathematical principles, Ptolemy's twenty-six pioneering portolani were published eighty years before the appearance of the first book of algebra in around the year 250. Even four centuries before that, Chinese ships were built that were able to reach India, with or without maps.

Obviously, exploration could achieve a great deal without a knowledge of advanced mathematics, but much more would be accomplished as greater mastery of time and space through mathematics evolved.

Meanwhile, the development of algebra in terms of negative numbers took centuries. Hindu mathematicians first developed negative numbers in the sixth century. While complex numbers were not actually used before the late eighteenth century, the Italian Rafael Bombelli developed them in the sixteenth century, though it was to take another century before the theories were applied.

Calculus, discovered about 1665, applies differential equations to many practical challenges – in mechanics, for example. These complex numbers would prove to be essential in engineering and physics, and by extension certainly in shipbuilding and navigation, as well as in sophisticated map-making.

Nicolas Kratzer, 1528. Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543). Oil on canvas, 83 x 67 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

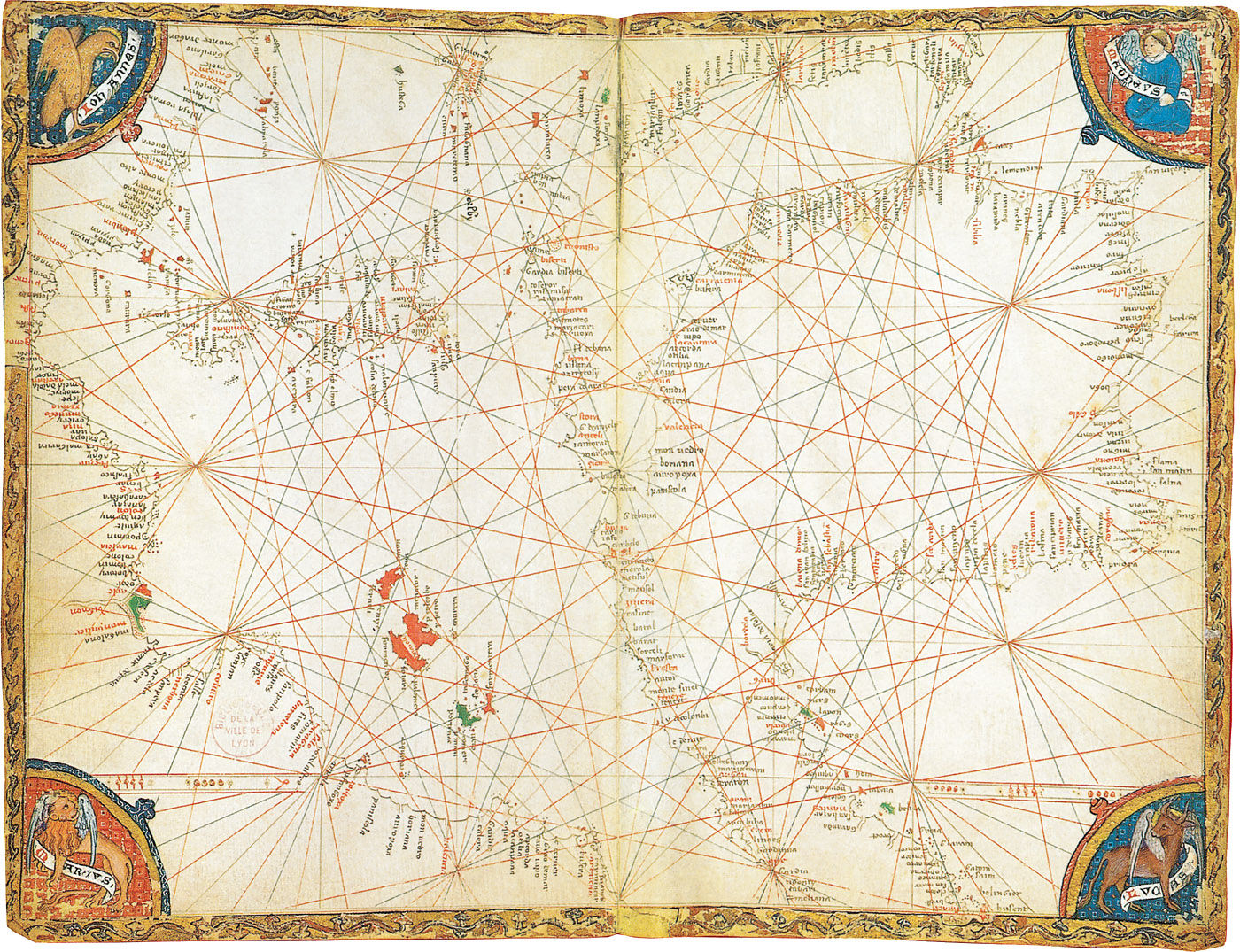

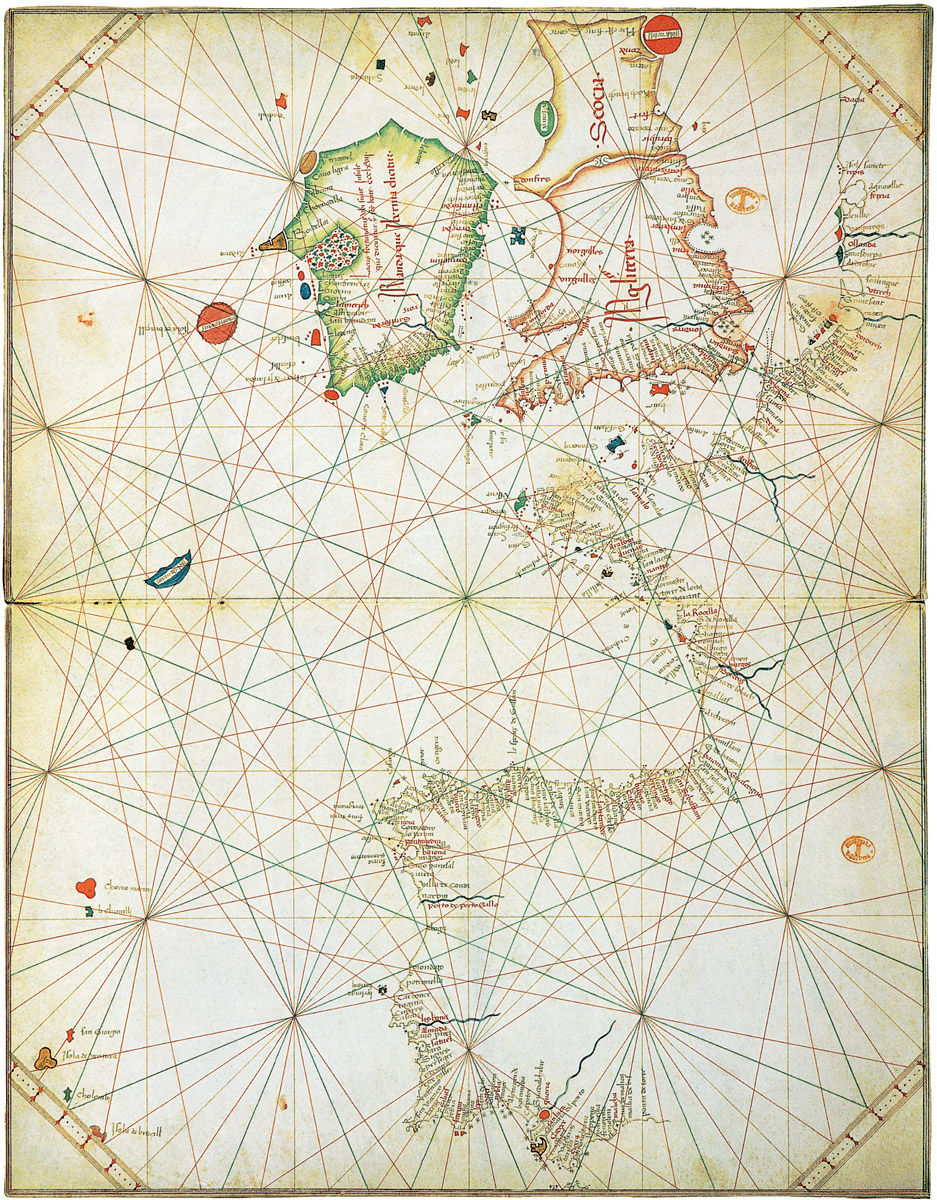

Atlas (French, English and Irish Coasts), c. 1321. Petrus Vesconte. Parchment stuck onto wood, 14.3 x 29.2 cm. Bibliothèque municipale, Lyon. (Map 6)

EXPLORING BEGINS: 300 B.C. – 1000 A.D.

Alexander the Great

During Alexander’s triumphant thirteen-year campaign of territorial expansion that began in 336 BC, he extended his empire from Macedonia to India, and along the Mediterranean coast southward including Egypt.

Because Alexander was a student of Homer and was fascinated by the figures of mythology, on his return from India he marched his army west through the desert of southern Iran towards Babylon – just as he thought great heroes of the past had done. He pressed on to Babylon and it was there that he died in 323 B.C.

Alexander was a military genius who used every opportunity to expand his territory by conquering everything in his path. Although his route of conquest was predominantly by land, he did assign a fleet of ships under his officer Nearchus to scout the northern coast of the Indian Ocean towards the Persian/Arabian Gulf. Nearchus’ coastal exploration, while limited, most likely contributed data that would eventually be used in the preparation of the coastal maps of the area.

Alexander’s western expansion undoubtedly spread Greek culture into Asia. It prepared that part of the world for the concept of obedience to a single King of a universal kingdom, which the Romans would build on for political gain, and later Christianity would accommodate to its aggressive apostolic purposes.

Erik the Red

A thousand years ago, the Scandinavian explorers known as the Vikings undertook journeys and left artefacts that remind the world of the contribution to civilisation made by these important pioneers (see illustration). Some came to North America to escape the political unrest in Norway, living for over two centuries in peace and eventually establishing the world’s oldest national assembly in around 1030.

Erik the Red, a descendant of Viking chieftains, established the first European settlement in North America. Around 981, he and his fleet of twenty-five ships discovered the land he named Greenland. He spent three years exploring the area. About twenty years later, Leif Eriksson (precisely, Erik’s son), most notable of all the Vikings, discovered Vinland, later to be recognised as North America – although there is continued dispute about exactly where the initial landing or first settlement was.

In around the thirteenth century, as Iceland became a Norwegian colony, many of the greatest Scandinavian sagas were written in the Viking language, which is still spoken in Iceland.

Leif Eriksson

In his Saga of Erik the Red, Eriksson records the contemporary accounts of the grandson of one of the earliest colonists of Greenland. ‘Our voyage must be regarded as foolhardy,’ the writer admits, ‘seeing that not one of us has ever been in the Greenland Sea’.

‘Nevertheless,’ Eriksson comments, ‘they put out to sea when they were equipped for the voyage, and sailed for three days, until the land was hidden by the water. Then the fair wind died out, and north winds arose, and fogs, and they knew not whither they were drifting and thus it lasted for [a long period of time]. Then they saw the sun again, and were able to determine the quarters of the heavens; they hoisted sail, and sailed that [period of time] through before they saw land. They discussed among themselves what land it could be, and [one of them] said that he did not believe that it could be Greenland. He asked whether it was desirable to sail to this land or not. It is my counsel (said he) to sail close to the land.’

The description of the coastline that is then described may well constitute the beginning of the first portolano of North America.[4]

In 1962, archaeologists unearthed the first hard evidence of a Norse presence in north-eastern Canada. L’Anse au Meadow at the very northern tip of Newfoundland was definitely a Norse settlement. A Norse coin dating from around 1070 was afterward unearthed at an American-Indian site in Maine. Moreover, ‘recent scholarship suggests that Vinland may have been off Passamaquoddy Bay, between Maine and New Brunswick. Wherever it was, it was the birthplace of Snorri, the first European child born in America.’[5]

The widow of one of the sons of Erik the Red married the Scandinavian explorer Thorfinn Karlsefni, a Scandinavian explorer born around 980. At the start of the second millennium, with three ships and 160 men, he attempted to establish a colony in North America, probably in about 1002, in what was thereafter called Newfoundland.

A collection of sagas known as Hauksbók and a section of another called the Flateyjarbók are cited as additional evidence, but it has to be admitted that these resources are mixtures of fact and fiction. We see a similar mixture again in the writings of Marco Polo, Columbus, and other explorers whose enthusiasm often influenced their documentation. Such imagination influenced their maps in general. For example, there are some unicorn-like figures indicating imaginedly weird native animals in a map within the portolano of the St Lawrence Bay area of between 1536 and 1542 by Pierre Desceliers.

Atlas (Spanish Coasts), c. 1321. Petrus Vesconte. Parchment stuck onto wood, 14.3 x 29.2 cm. Bibliothèque municipale, Lyon. (Map 5)

Oseberg Ship, c. 817. Oak and pine wood, 22 x 5 m. Found in 1903 in a burial mound next to Oseberg. Norsk Sjøfartsmuseum, Oslo.

COMING OUT OF THE DARK: 1000–1400

Marco Polo

Every textbook of world history mentions the Venetian Marco Polo and his amazing fourteenth-century travels in China. It is quite possible, however, that he never visited Asia at all. The accounts of his travels attributed to him may be simply very clever fiction. But it is more likely that when he was seventeen Polo did indeed accompany his grandfather and uncle, successful jewel-merchants, on their second trading journey to China during the last quarter of the thirteenth-century (see illustration).

Either way, the descriptions of Polo’s seventeen years of journeys are told in The Book of Ser Marco Polo – which for centuries was one of the most influential literary works in Europe. It could even be said to have laid the foundation for the Age of Discovery. Two centuries after its first publication, a printed copy was owned and studied by Columbus. In fact, Columbus made specific attempts to identify some of the islands he visited in the Caribbean as locations described by Polo.

While in prison, Polo apparently related the details of his journeys to a fellow prisoner, who conveniently happened to be a popular writer of romantic fiction. It may be that Polo merely heard these tales while sojourning in Constantinople or in the ports around the Black Sea – the episodes are not unlike typical ‘fishing stories’, openly exaggerated in order to entertain. Appropriate musical accompaniment to listen to while reading about his travels might perhaps be Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade (see illustration).

In a university dissertation on the literary styles exhibited in the works of Marco Polo, Enrico Vincentini (University of Toronto, 1991) notes that Polo’s account of his travels can be considered a ‘lost’ book, a book of which modern editions are no more than ‘conjectural reconstructions’ of the original corrupt manuscripts.

In any edition (or ‘reconstruction’) of Marco Polo’s book, the descriptions are always exaggerated. Whatever he was counting, there were never less than thousands and even hundreds of thousands. Moreover, nearly every time hyperbole is used, the writer introduces it with such expressions as ‘I give you my word …’ or ‘I assure you …’ which is distinctly similar to the style of storytellers passing on obvious myths and legends. It is a literary device that was not uncommon to the non-fiction of the day, and of course had already been discernible for centuries in the scriptures of various religions.

How much of the Marco Polo work was the product of the writer’s imagination – or the writer’s enthusiasm – may never be known. What we do know is that the work inspired adventurous people for hundreds of years thereafter. Even map-makers, whom we might expect to be scientific as much as artistic, incorporated imaginary figures into their work, as seen in several maps here reproduced. These maps often exhibit truly vivid imaginations together with genuine data from scientific exploration. A serious study of them requires a specialised glossary and a knowledge of the history of their time (as, for example, displayed in Ellen Bremner’s university dissertation on the subject: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1961).

The first journey east by the Polos was the also the first purely trading venture by Europeans in China. Previous visitors from Europe had been Papal representatives and religious missionaries who were taking literally the gospel passage ‘the Good News must first be proclaimed to all nations’ (Mark 13:10).

The Mongols, with their history of violent behavior, were deemed to be in special need of Christianity, even if it required similar violence to effect their conversion.

As with many of the great discoveries throughout history, what was actually found to be there proved to be a surprise, and in some ways more desirable than what was being sought. Navigators for at least three centuries after the Polos looked for new routes to the countries that they already knew about, not for new countries as such. It is not surprising therefore that none of the editions of The Book of Ser Marco Polo included maps, although ironically many details in maps for centuries thereafter were inspired by it.

The first expression of Polo’s journey in map form came after his death (1324) in the Catalan Atlas (1375) (see illustration). Many of the places named in the legend in that atlas appear previously only in Polo’s descriptions.

Tribes of Danes Crossing the Sea to Britain, in Life, Passion and Miracles of Edmund of England, 1125-1135. Alexis Master and his workshop. Miniature on vellum. The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

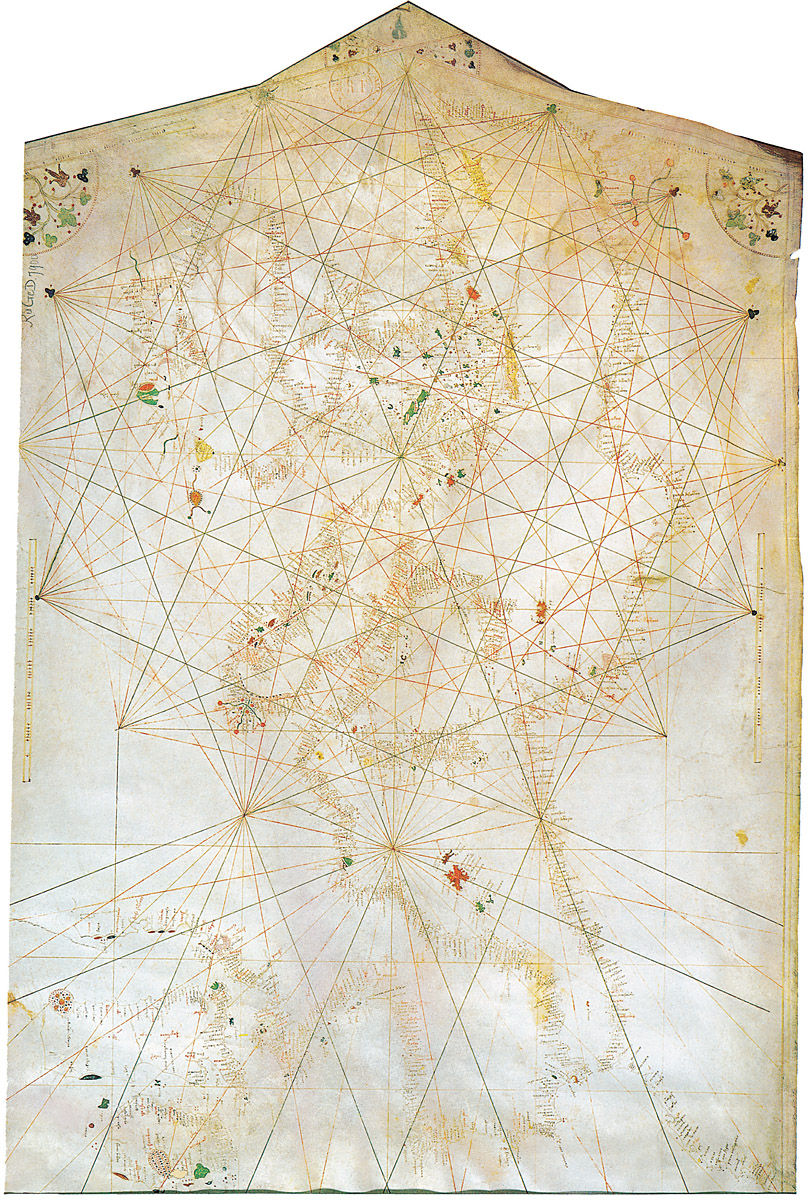

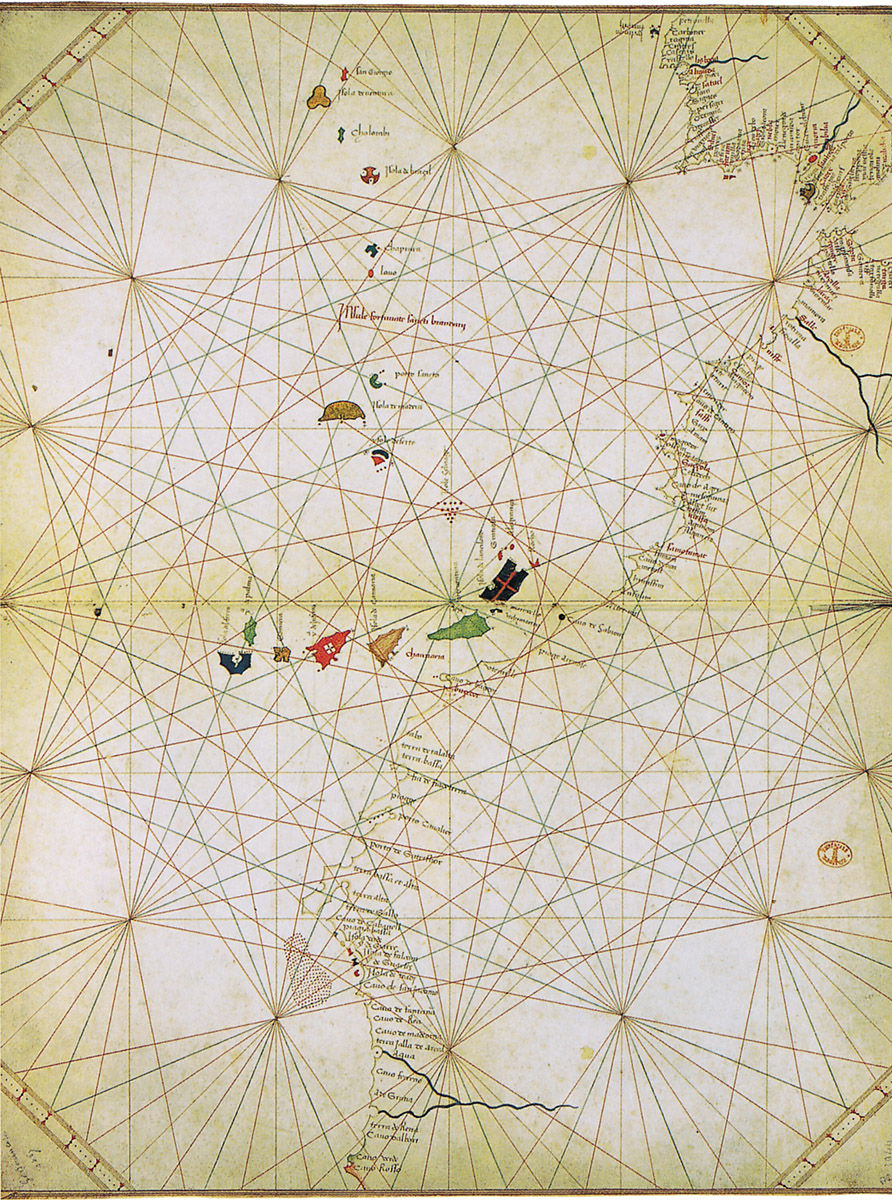

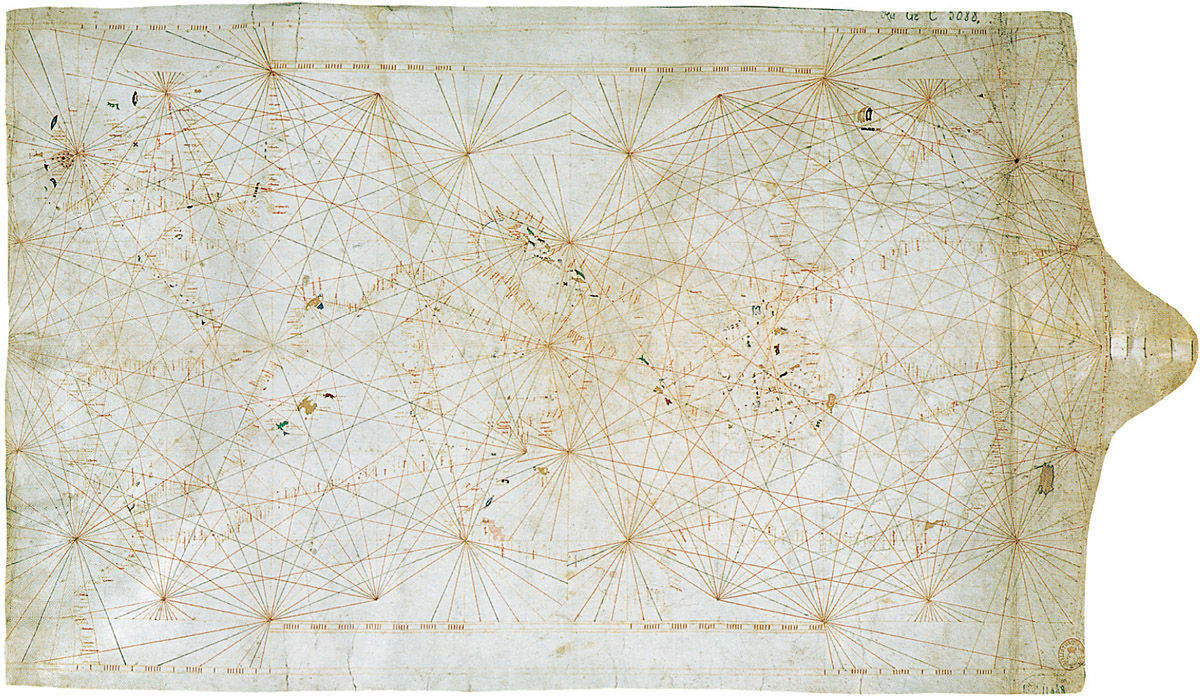

From the Baltic Sea to the Red Sea, 1339. Angelino Dulcert. Parchment, 75 x 102 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 7)

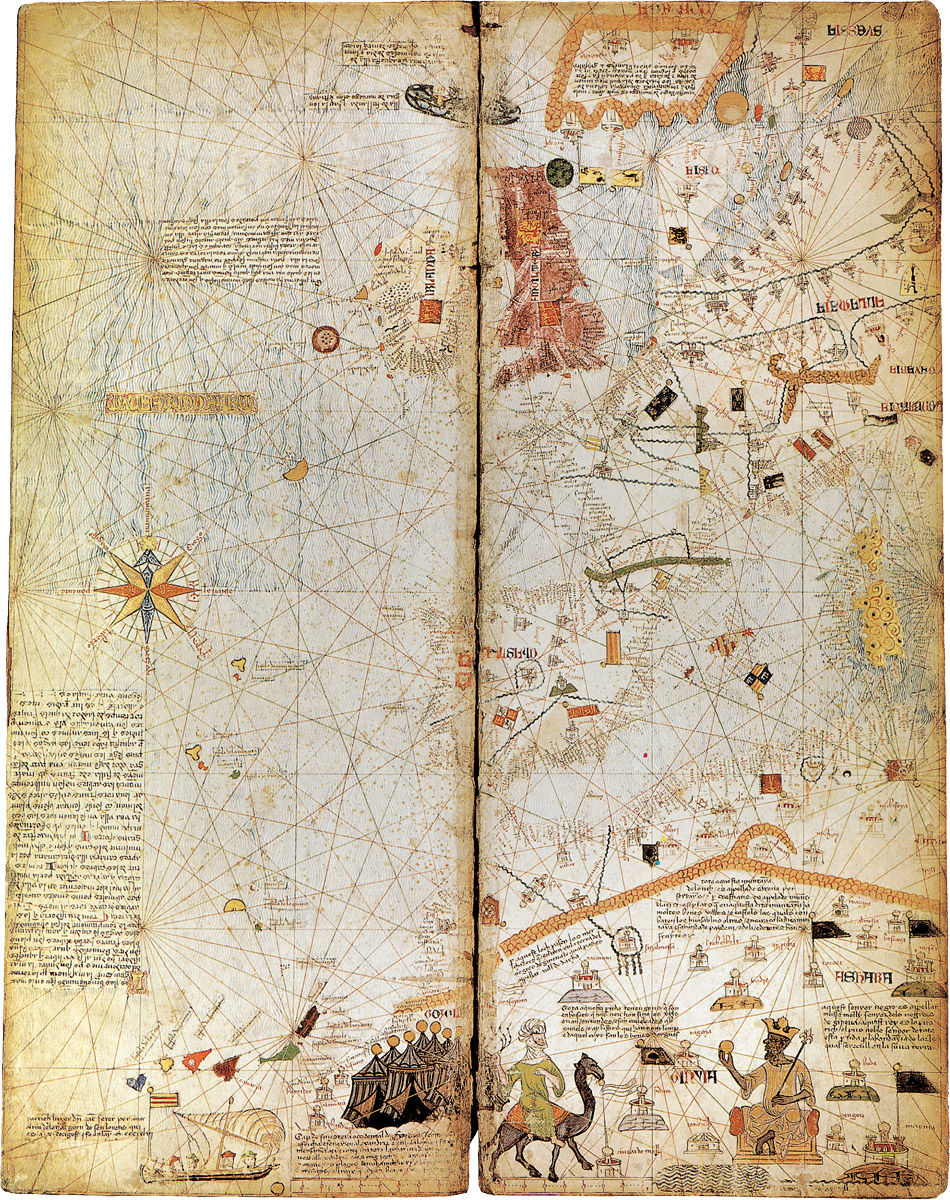

Catalan Atlas (Atlantic Ocean and Western Mediterranean Sea), c. 1375. Abraham Cresques. Parchment on wood tablets, 64 x 25 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 8)

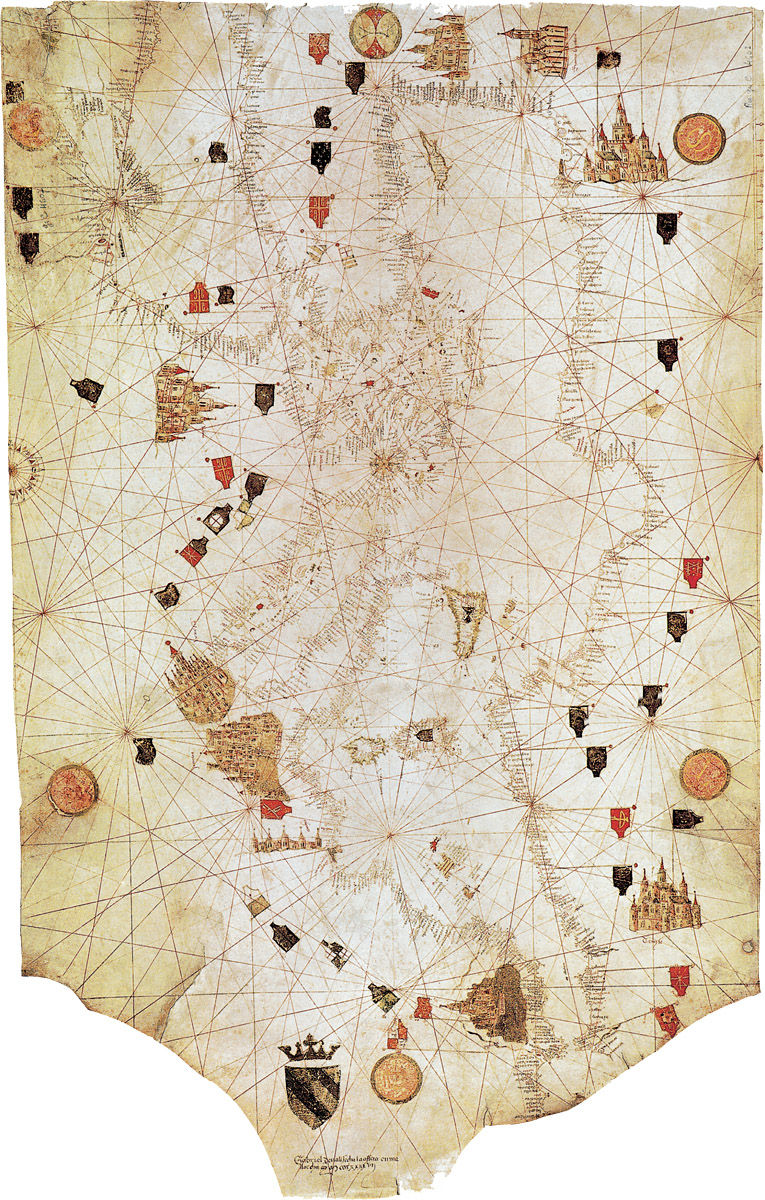

Mediterranean Sea, c. 1385. Guillelmus Solieri. Paper, 102 x 65 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 9)

The Franciscans

Two well-traveled Franciscan friars – Joannes de Plano Carpini in 1245 and William of Rubruquis in 1253 – were notable among the influential clergy. Their tales were less fanciful than those of Polo, but were often just as outlandish. They included descriptions of luxurious silks and other exotic artefacts desired by Europeans. Ironically, the stories brought back by these well-intentioned friars encouraged journeys by others who were not so ethically-minded. Soon Europeans returning from China managed to smuggle silk worms into Europe – risking their lives by doing so – in order to produce the much-desired fabric in Europe.

Spices then replaced silk as the most yearned-for imports, and the so-called Spice Islands (Indonesia) became the new favourite destinations for the trading enterprises (see illustration).

The memoirs of other Franciscan missionaries (Giovanni di Monte Corvino in 1294 and Odoric of Pordenone in 1318) supplemented the descriptions of China by Marco Polo, but their concern was again not to create maps but primarily to convert the ‘idolaters’ and ‘cannibals’ to Christianity. Nevertheless, Monte Corvino was the first to report the monsoon cycles that were later vital to understanding sea-routes to India, as we will see with the pioneering voyages of Vasco da Gama and after him Pedro Cabral.[6]

Columbus described the native Indians of the West Indies as cannibals. His shipmate and friend from boyhood Michele da Cuneo said that they castrated teenage prisoners so as to ‘fatten them up and later eat them’.[7]

Henry the Navigator

Seventy years after the death of Marco Polo, a Portuguese prince was born who would be even more instrumental than the Polos in advancing the Age of Discovery. He would become the fifteenth century’s leading promoter of exploration and the study of geography.

Although the Prince came to be known as Henry the Navigator, he did not actually do any navigating on the pioneering Portuguese explorations along the coast of West Africa for which he gained his renown. Rather, he organised and sponsored them after several of his own earlier expeditions were financially unprofitable.

As previously noted, many explorers then and thereafter have been motivated by what some have called ‘God, glory, and greed’. Henry the Navigator was certainly not alone in wanting to convert pagans to Christianity, advance geographical knowledge and acquire gold.

After a decade of attempts by others, one of Henry’s navigators, Gil Eanes, finally rounded Cape Bojador (on the north-west African coast just south of the Canary Islands) in 1434. It was an area that was seen – mainly because of superstition – as a major obstacle between Europe and the Indies. In fact, Henry apparently told Eanes to either push beyond that point this time or to not return. Of course it was to prove to be only an early hurdle in a much longer journey, but new information from his trip was incorporated into maps by Grazioso Benincasa in 1467 [Maps 18–19].

About five years later the Portuguese colonised the Azores, which they had discovered in 1427. Expeditions then continued along the coast, mapping the West African coast down to present-day Sierra Leone. Unfortunately, the further the Portuguese went, the more they took to looking not just for gold but also for slaves to make a profit on as well.[8]

Michele da Cuneo, the long-time friend of Columbus, described the enslavement of the natives of Haiti before returning from the second voyage. ‘We gathered in one settlement one thousand six hundred male and female persons of these Indians, and of these we embarked in our caravels on 17 February 1495, five hundred fifty souls among the healthiest males and females.’ His journals go on to tell how about two hundred of these enslaved Indians died during the return voyage and were thrown overboard.[9]

Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea, 1409. Albertin de Virga. Parchment, 68 x 43 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 11)

Venetian Atlas (Western Mediterranean Basin, Portugal, Spain and Western France), c. 1390. Unknown artist. Parchment on wood, 23.5 x 15.5 cm. Bibliothèque municipale, Lyon. (Map 10)

From the Baltic Sea to the Niger, 1413. Mecia de Viladestes. Parchment, 85 x 115 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 12)

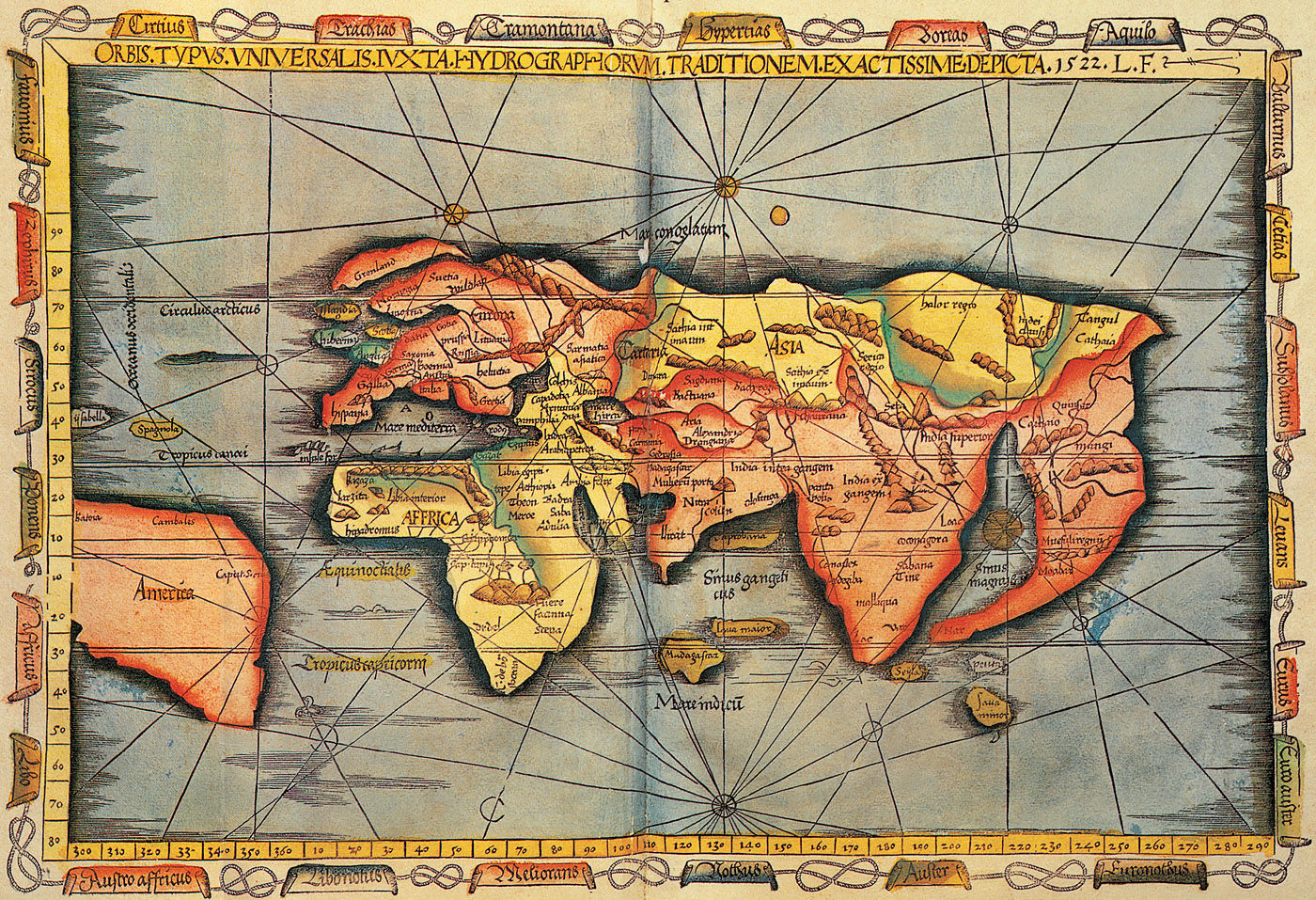

Orbis Typus Universalis Iuxta Hydrographorum Traditionem Exactissime Depicta, 1522. Reworking by Laurent Fries of Martin Waldseemüller’s 1513 Ptolemaic map for publication. Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice.

Liber Insularium Archipelagi (Corfu), 1420. Christoforo Buondelmonte. Coloured paper, 29.5 x 20.5 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 13)

Liber Insularium Archipelagi (Chios), 1420. Cristoforo Buondelmonte. Coloured Paper, 29.5 x 20.5 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 14)

PORTOLANI DURING THIS PERIOD [10]

The Pisana School

The Pisana [Map 1] is the earliest example (1250–1296) of a portolano. It is the oldest Western navigation map, and as an extremely early (and well known) map influenced all subsequent maps, especially those of the Catalana and Genovese schools. Although it may have been drawn up in Genoa, it is referred to as the Pisana map because it belonged to a well-established family in Pisa during the nineteenth century. It depicts the Mediterranean Sea in correct proportions.

The Early Genovese School

The portolani of the Genovese school (1300–1588) in this presentation [Maps 2–6] were directly influenced by the pioneering thirteenth-century work. In turn they substantially influenced the fourteenth-century Viennese and sixteenth-century Portuguese, Spanish and Italian schools.

Spanish and Italian Schools

Other portolani of the Genovese school include Maps 21, 23, 24, 26, 41, and 56. These also directly influenced the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Portuguese, Spanish and Italian schools.

The corners of Maps 5 and 6 are decorated with popular patron saints of Venice, including St Nicholas and St Lucia.

Two anonymous Genovese maps of around 1500 [Maps 23 and 24] were drawn by the same map-maker using inks similar to those used by the Japanese at about the same time. The peninsular coasts from Vlorë (Valona) in Albania to the Pagasitikós Gulf in Thessalia are represented in the unfinished map of the Greek coasts [Map 23]. In the other map [Map 24] the coastlines of the Aegean archipelago are shown. It is oriented to the north-north-west, showing a new awareness of magnetic north.

Map 25 is known as Cantino’s Planisphere (1502), one of the earliest examples of Portuguese maritime cartography. It represents the whole of the known world at the time, including recent Portuguese discoveries of up to 1502. The design was influenced by the miniature-painters Alexander Bening and Guillaume Vrelant.

The large maritime planisphere of Genoan cartographer Nicolaus de Caverio [Map 26] bears comparison with Cantino’s Planisphere [Map 25]. It features nomenclature in Portuguese. However, it does not include information from discoveries after 1504. Its graduated latitude scale is an innovation not seen in maps before the sixteenth century. It is a highly derivative work. The same design and nomenclature are seen in the work at Saint Dié of Waldseemüller, who was responsible for the first oceanic map in the extremely influential 1513 edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia.

The Caverio Planisphere outlines the shape of the Indian subcontinent correctly, but does not feature the Red Sea or the Persian/Arabian Gulf – areas the Portuguese had yet to visit.

Marco Polo Leaves Venice on his Famous Journey to the Far East, in Roman d’Alexandre, c. 1400. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Marco Polo with Elephants and Camels Arriving at Hormuz on the Gulf of Persia from India, in Les Livres des Merveilles, early 15th century. Boucicaut Master. Miniature. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

World Map (detail), in Atlas Catalan, 1375. Abraham Cresques. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

The Catalana School

Early portolani [Maps 7, 8, 9, 12, 16, 17] of the Catalana school at Majorca (c. 1290–1330) also exhibit the long-lasting influence of The Pisana [Map 1]. Even later examples [Maps 62, 64, 65, 68] of as late as 1649 also influenced the Portugese, Italian and Spanish schools from the fifteenth century on, as well as the Messina school of the mid-sixteenth to late seventeenth centuries.

A synthesis of the whole known world is attempted in Map 7. Unlike previous maps in this collection, the nomenclature inland is important. On the map in the south of Africa is a region named as Terra Nigrorum.

In Asia, the Caspian Sea (Mare de Bacu sive Capium) is named. Three of the Canary Islands are specified for the first time. The Majorcan school, of which this map is typical, was to be imitated for centuries.

Map 8 may have belonged to King Charles V of France, possibly as a gift to him from King John I of Aragon.

On Map 9 the cartographer indicates in Latin that Europe is ‘where Christians live’. Biblical sites and pilgrimage destinations are indicated, including the Holy Sepulchre (the traditional location of Jesus’ entombment), St Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai, and Mecca.

The emblem of the Cornaro family, a contemporarily renowned clan, is shown on Map 10. Some coasts are drawn disproportionately close to each other.

The symbols of the four New Testament evangelists feature in the corners (clockwise from the upper right, Matthew is symbolised by a man, Luke by the winged ox, Mark by the winged lion, and John by the eagle).

Some important African warlords are represented. One of the ships near the African coast is that of the 14th-century Aragonese pirate Jacme Ferrer, who is represented also by a ship on Map 8. Sites are indicated where Arabian sources claimed gold was to be found.

That sort of information was usually closely guarded by merchants.

The impressive quantity of Joan Martines’ output is seen again (as in Map 62) with his twenty-one parchment sheets that make up the Atlas dated 1587 [Maps 64–65]. His main source seems to have been the 1569 world map of Gerardus Mercator. This is a compilation of nineteen maps.

The maps may have been commissioned or intended for use by King Philip II of Spain – who at the time was preparing an armed (armada) expedition against England. It is Philip’s coat of arms shown on the map.

Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea, 1447. Gabriel de Vallsecha. Parchment, 58 x 93 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 16)

Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea, 1462. Petrus Roselli. Parchment, 53 x 83 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 17)

Atlas (Atlantic Ocean from Spain to Cape Verde), 1467. Grazioso Benincasa. Parchment stuck on card, 34.9 x 44.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 18)

The Viennese School

The portolani of the Viennese school (1567–1690) presented here [Maps 10, 11, 15, 18, 19, and 76] show the influence of the Genovese school. Their own unmistakable influence was primarily on the Spanish school, the Barbary Coast school in Istanbul and the Marseille school.

A close examination of Map 11 reveals that the artist sketched the outline with a dry point before drawing in the final version. The Black Sea is conveniently reduced in size so as to fit within the allotted space. The French coastline is somewhat cursorily dealt with, whereas the coasts of England are delineated in some detail. The map-maker endeavors to make light of such inconsistencies by presenting three different scales against which to estimate distance.

Symbols that were standard in medieval iconography are used in Map 15, including the red cross for shallows or sandbanks, and blue lines for lateral cordons.

As a young man in the mid-fifteenth century, Grazioso Benincasa kept a diary of his trips sailing across the Mediterranean and Black Seas. After losing his ship to pirates, he became a cartographer famous for producing more than twenty-two works between 1461 and 1482.

We noted above that details of Africa included in this atlas had only recently become known following the return of the explorer-navigator Gil Eanes. Yet in 1467 Benincasa was apparently quite prepared to use out-of-date information for the maps of northern Europe in his atlas, in which he included Maps 18 and 19.

A cartographer of the Dutch East India Company, Hessel Gerritsz, drew up his map of the Pacific [Map 75] in 1622. All the recent discoveries are noted, along with unique artistic tributes to Vasco de Balboa, Ferdinand Magellan and Jakob Lemaire. A world map, though very small, is also featured.

Because of its importance to the area, the Aegean Sea was often depicted disproportionately large in maps of the Middle Ages. The whole of the map produced in 1603 by Alvise Gramolin [Map 76] is devoted to the sea and its coastline. All the flags and shields show the crescent moon from Muslim and Ottoman icongraphy, for the archipelago was under Turkish influence at the time.

Mediterranean Sea, 1422. Jacobus de Giroldis. Parchment, 88 x 51 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 15)

Atlas (Atlantic Ocean from Denmark to Malaga), 1467. Grazioso Benincasa. Parchment stuck on card, 34.9 x 44.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. (Map 19)