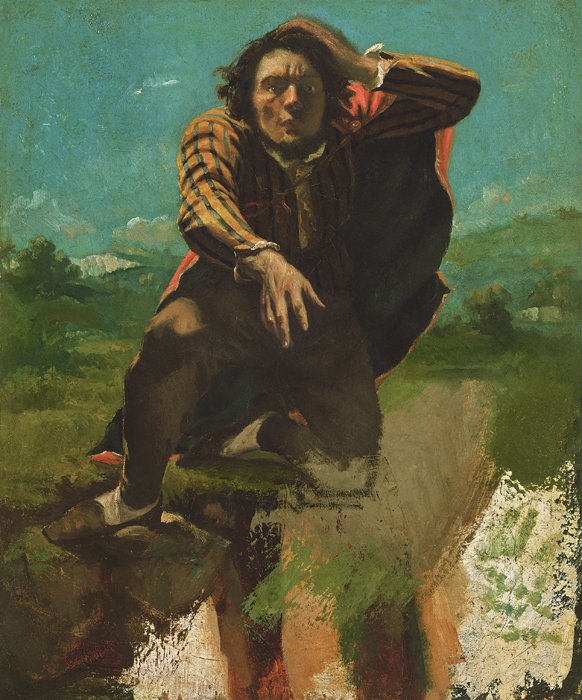

4. Portrait of the Artist, known as

Mad with Fear, 1848 (?).Oil on paper

mounted on canvas, 60.5 x 50.5 cm.

Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst Arkitektur og Design, Oslo.

I. The Beginnings

Paris and the First Salons

The First Exhibitions in Paris

However excited Courbet must have been on his arrival in Paris, one can easily imagine that it was not long before pangs of homesickness set in. He tried to improve his spirits by visiting compatriots from Franche-Comté, either relatives or friends, who consoled him as best they could. Relations with his cousin Oudot, the professor at the School of Law, soon became strained; he was no doubt disappointed that the young man should so quickly give up a career in the law for painting. Courbet’s life was humble and uncomplicated. He seems to have taken lodgings for quite some time in a hotel, located at number 28 in the rue de Bucy, but the place was short on creature comforts, and Courbet wrote urgently to ask that sheets, a blanket, a pad and a mattress be sent from Ornans.

Soon, in a letter of the 24th of December 1842, he announced to his parents that he had finally found a studio, at 89, rue de la Harpe; “It is a fine room with a wooden floor and a high ceiling, which will be warm in winter; the studio is upstairs, on the courtyard, and has two windows, one looking out on the courtyard, and the other in the roof.”

From then on he spent long and fruitful hours visiting the galleries of the Louvre. Francis Wey relates in his Mémoires inédits (Unpublished Memoirs) that the fine fellow of a painter, François Bonvin, whose conscientious talent has not yet been properly appreciated, acted as a guide for his young friend.

Courbet was instinctively drawn to the masters who best exemplified the as yet unfocused ideas developing within him. He had no use for the Italian school. Later, Théophile Silvestre, recording a conversation that he had just had with the master, said that Courbet called Titian and Leonardo da Vinci “frauds”. As for Raphael, he conceded that he might have done a “few portraits that were interesting,” the works nevertheless “show no thought,” and that is why, no doubt, continued Courbet, “our so-called idealists adore them.” It is quite likely that he did actually say these things. But one must not give too much importance to these witticisms, which smack of an artist out to shock the critics, who were always the painter’s bête noir, and the bourgeoisie for whom he showed a profound scorn, as did many artists of his time.

In his disapproval of the Italian school, he made an exception for the Venetians; Veronese, and among others, Domenico Feti and Canaletto. Did he study the techniques of the Bolognese artists: the Carracci, Caravaggio or Guercino? Everything points to their influence on him having been exaggerated. He particularly admired, and studied, the great realists such as Ribera, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Van Ostade, Holbein, and, first and foremost, Rembrandt, who “beguiles the intelligent, but bewilders and overwhelms the slow-witted.”