Preface

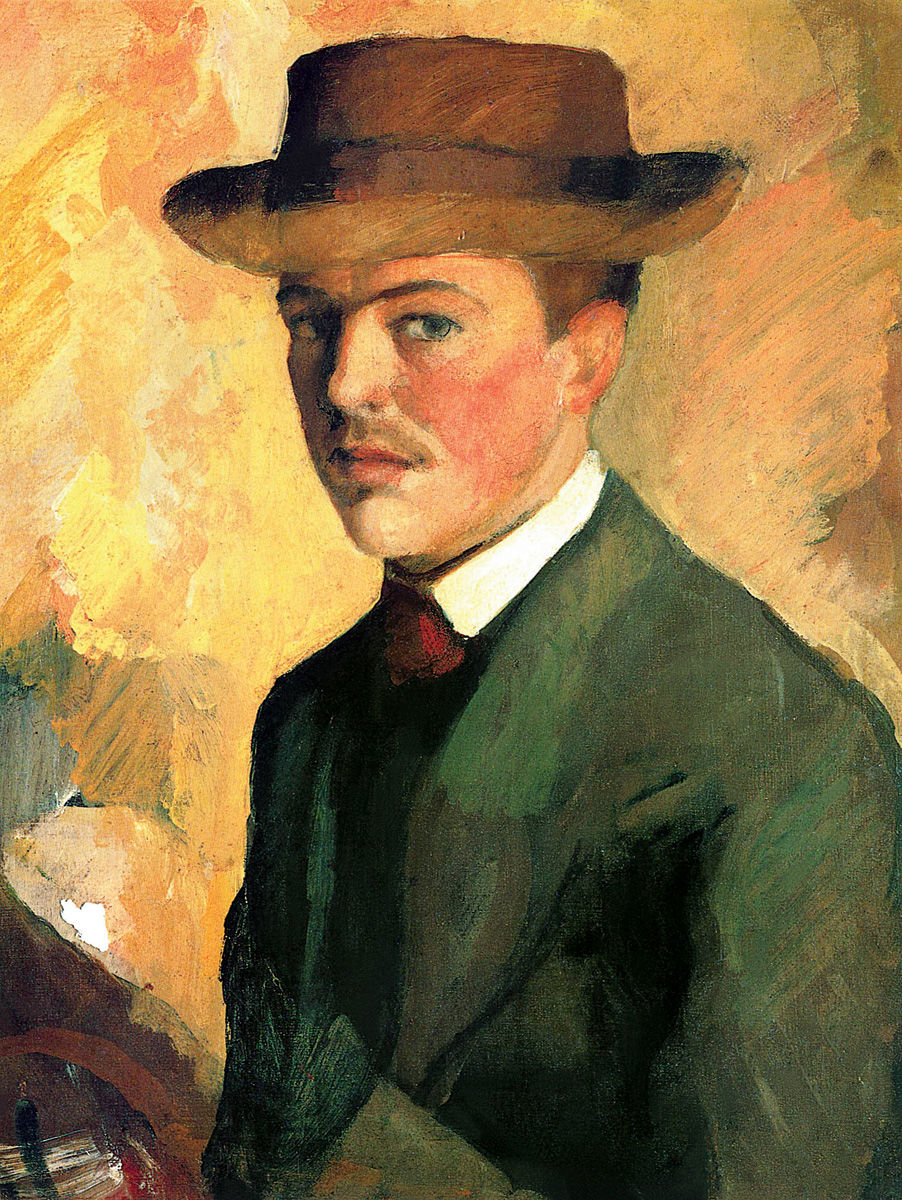

August Macke (1887-1914) was born in Meschede in the Sauerland region and is of Westphalian origin. However, as he moved into the Rhineland very early and spent most of his short life on the Rhine, he has always been described as a typical Rhinelander.

When the Cologne Art Association opened the near-historical exhibition ‘The Young Rhineland’ at the beginning of 1918, the heart of the event was the first retrospective exhibition for August Macke, who died in the second month of the war. “Young Rhineland” represents Macke in a purer sense than the well-known artist association that was founded later in Düsseldorf. Anyone who dismisses Macke’s art with the term “decorative” fails to understand that the young Rhenish artist’s paintings signify everything that defines character and strength.

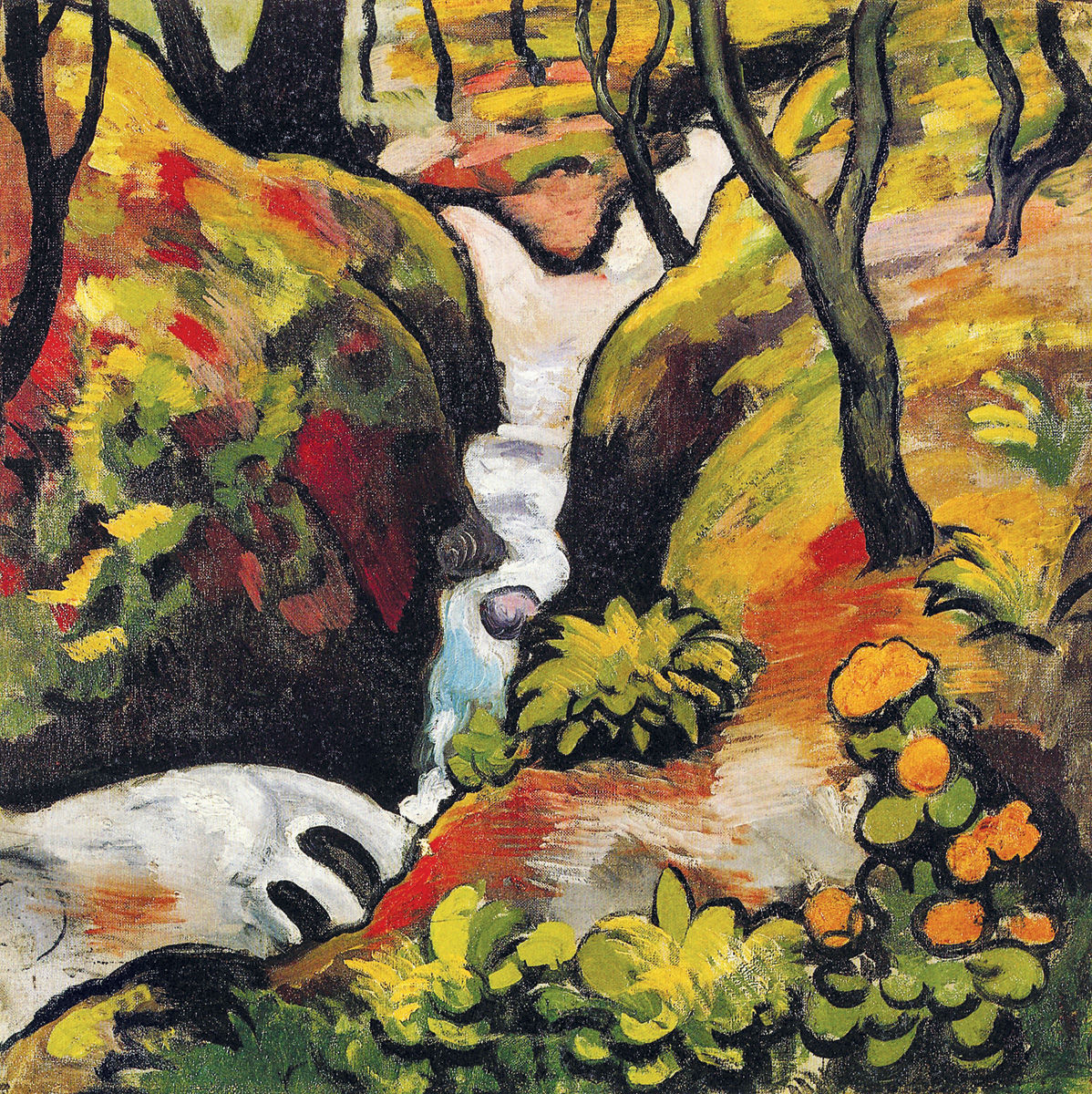

This art is largely attributable to its optical appearance which is closely interlinked to the indescribable joy and richness of colour of the Rhenish landscape. Earlier Düsseldorf artists were also attempting to reproduce these same landscapes, but the majority of these productions, with the exception of the German illustrator and painter Caspar Scheuren (1810-1887), appear extremely pale and unreal.

Macke also focussed on the appearance of objects, and did not always avoid veduta-like productions. You may look in vain for the healthy Rhenish sensuality in the later productions of the Romanticism on the Rhine, even where it remains totally terrestrial.

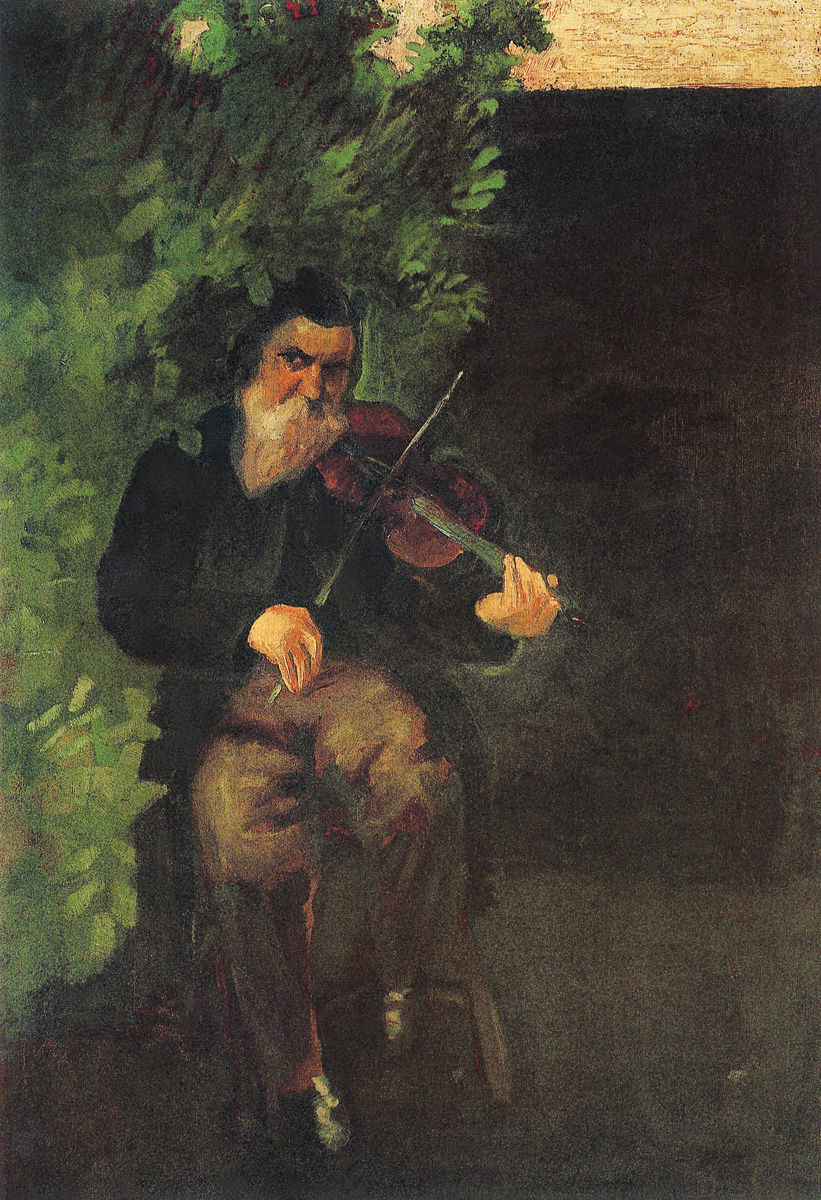

Fisherman on the Rhine, 1907

Oil on cardboard, 40.3 x 44.5 cm. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich

Whilst Macke looked for the soul of things, the appearance of his works was not unfaithful, as substantiated by his work The Rhenish Landscape with Factory (1913). The subject for this painting was literally on his way when leaving the northern parts of Bonn where his home was located, in order to walk to the Rhine. And there, encamped behind the seven mountains, was the factory; for most people a frustrating contrast, but the painter counted it a blessing and much more than just a “theme”.

The then 26-year-old artist, with the resources of early Expressionism and his own range of colours, so rarely seen amongst the palettes of professional landscape artists, had created the unity of nature and audaciously integrated work of man. The remarkable sureness of his design, which shows up in this small picture, can already be found in his very early works, such as the Naked Girl with a Headscarf (1910).

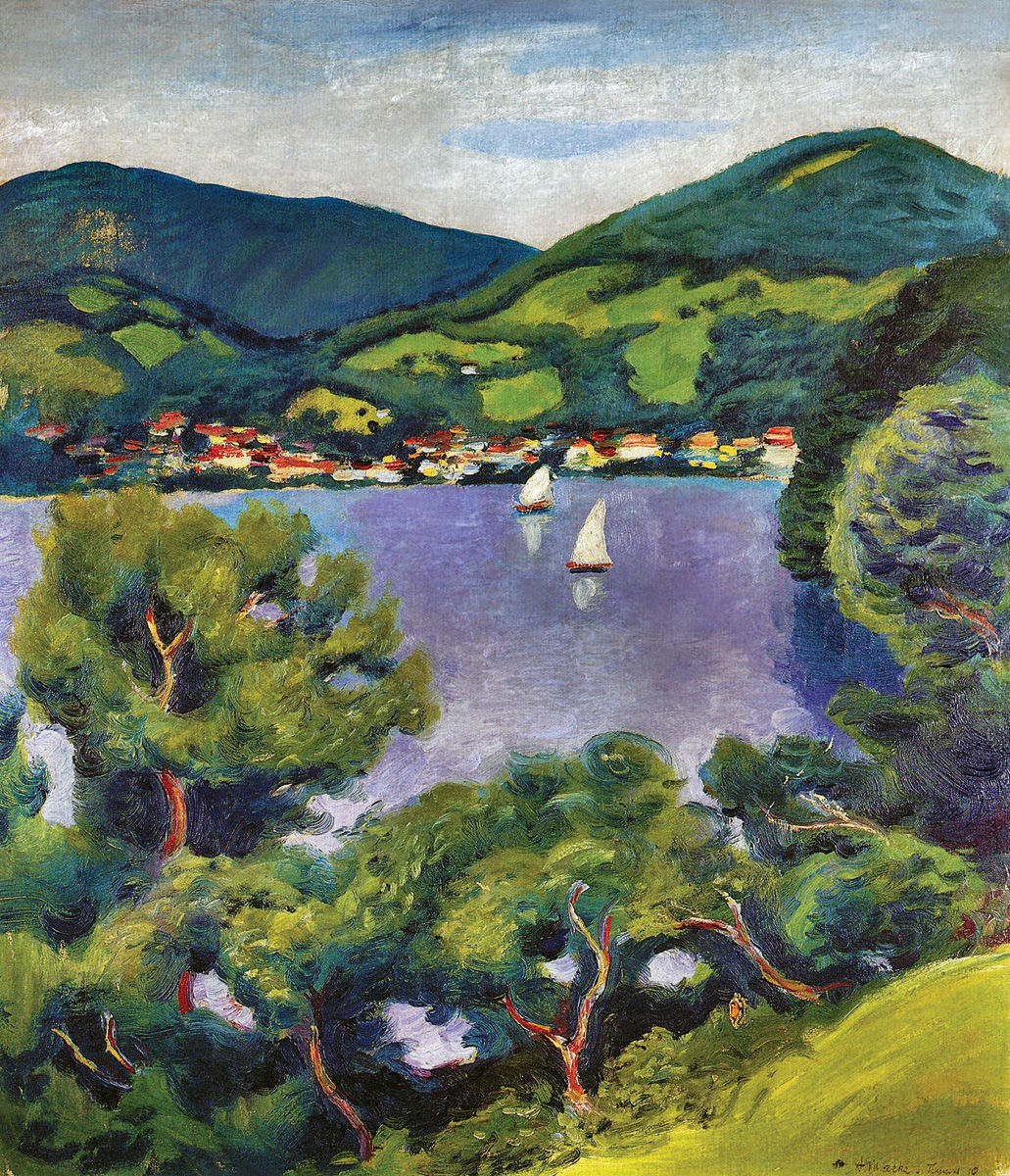

Macke spent a short time at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. However, he owes more to Paris, which he frequently visited. Of the younger artists in Paris, Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) was closest to the Rhinelander. More important was his friendship with Franz Marc (1880-1916), which was forged in 1909 in Tegernsee, where the newlywed had spent some time with his young, and rarely sympathetic, wife. In the first volume containing his letters, recordings, and Marc’s aphorisms, published in 1920, Macke dedicated ten of the most beautiful aspects of his friendship with Macke, including an obituary from the battlefield of 25th October 1914. I hope this will finally put an end to the legend that Macke was only on the receiving end in this friendship. For me, there never was the slightest doubt that the younger artist was superior in originality of his pure artistic talent to the somewhat doctrinal painter of the “Blue Horses“. In Bavaria, Kandinsky (1866-1944) entered into a friendly relationship with Macke; the artists associated with the Blue Rider saw him as a younger brother and loved him for his genuine and cheeky personality.

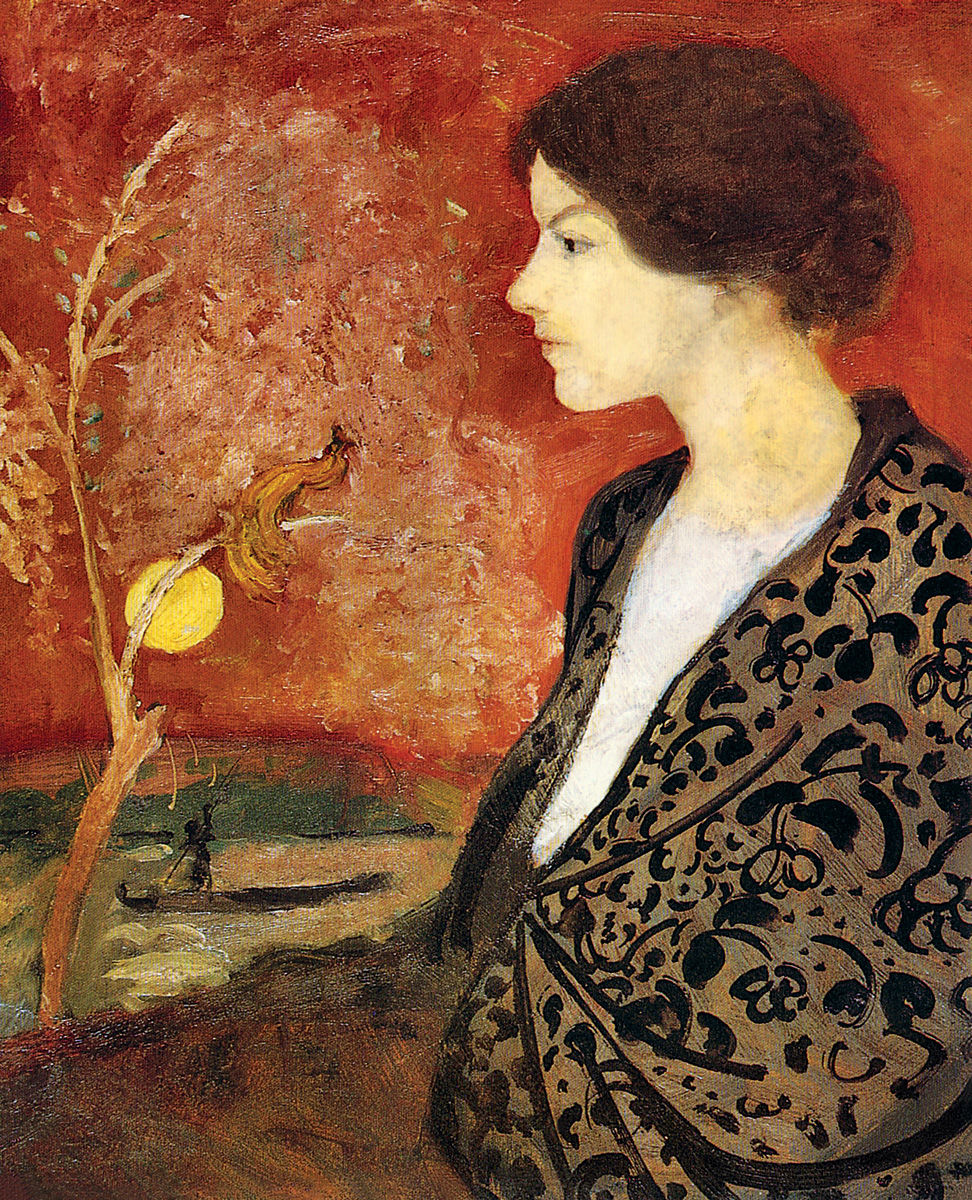

Study for a Portrait of Elisabeth Gerhardt (from memory), 1907

Oil on cardboard, 41.6 x 33 cm. Private collection

In 1913, Macke sojourned for some time with his family in Hilterfingen at Lake Thun, in Switzerland. It was probably one of his happiest times, not least for the progress in his artistic work. The following year, along with his friends Paul Klee (1879-1940) and the Swiss painter Louis Moilliet (1880-1962), he travelled to Africa. Macke, whose art culminated at such an early age, produced his strongest works from Tunisia, especially the sparkling little oil paintings from Tunis. These include, for example, the different versions of the Turkish cafés.

Here again, Macke was a typical Rhinelander, because of this empathy which had once placed the old Colognians into a dangerous dependency on the Dutch, such as Dirk Bouts (1415-1475), assimilating foreign influences on the design. These designs are not completely assimilated in all cases; there are paintings by Macke, especially those which are flirting with Cubism, that remain experimental and are not entirely convincing. Macke is always at his best when he combines colours with his peculiar sense for bouquet-like eurhythmics together; strong, lively, bright colours, as in the 1912 picture of the Four Girls in the Museum Kunst Palast in Düsseldorf (since 1918). What may perhaps have seemed a little hard in early images became, since his trip to Africa, radiant and warm. It is impossible to say what Macke could have given us, had he survived the war.

“We, the painters, are well aware,” wrote Franz Marc, “that with the elimination of its harmonies, the colour in German art will have to fade by several tone sequences and will become a duller, drier colour tone. Out of all of us, he has given the brightest and clearest shades to colour as clear and bright as his whole nature was. Certainly, the Germany of today does not realise how much it owes this young, dead painter, how much he worked, and how much has been achieved.“

Marc’s Germany of Today is the one of 1914. In the Germany which strove to overcome and resurrect itself with superhuman effort amidst outer and inner turmoil after the war, human beings like Macke had become increasingly rare. Macke was a young, truly gifted man of good cheer and perfect health, whose serenity of mind was contagious. A mutual friend saw Macke just prior to leaving for war at his home on Thun Lake, and after he had taken his leave and driven by the small cottage on the steam boat, the artist appeared again in unsouciant morning clothes, under the projecting roof, and towering like a giant: “With joyful movements of his whole body, he laughingly waved goodbye.”

On 26th September 1914, August Macke was hit by a fatal bullet near Perthes in Champagne.

Macke on “The New Program” [1914]

The tension between things in nature moves us. We respond to this stress by seeking to shape it.

Life is indivisible. Life in image-form is indivisible. Life in images is the simultaneous tension of different parts.

The vitality of tension decreases the more similar the parts and the whole group: the noise of water droplets or of a water pipe. A painted canvas.

The vitality of tension increases with the non-uniformity of parts and groups. A sonata by Mozart. A still life by Renoir or Cézanne.

Excerpts from old pictures show mostly peaceful transitions. The individual tensions usually go together with the total tension in calm contrast. (There are of course exceptions, such as Greco). Space-creating colour contrasts as opposed to simply chiaroscuro seems to me to have been recognised first by Delacroix and the Impressionists in its full meaning for the liveliness of the painting. Since then, artists have always attempted to use this means to lay down a uniform format of the pictorial space.

In Pissarro and Signac’s works, for example, the contrasting groups are present. But they are more similar to each other, more juxtaposed than the letters on a printed page, so that an almost grey impression of the entirety is created. For Cézanne, the contrasting groups are controlled to a simultaneous whole, so that the impression is more like the closed unit of a single initial.

A peculiarity of the “new” images is that in all sections, contrasting groups are to be found, in any colour; a successive rebounding red-greenish-yellow or more formal; colliding surfaces and edges.

Most of the new images appear to me to be designed so that the sharp universal contrast of the diverging groups is the means of composition, as opposed to a smooth falling-into-place of contrasting groups in previous works. I believe that in striving to shape a more active life in the image through the contrast, most of the “new” painters are similar in all the diversity of their individual interests. Picasso leaves the rest of his old masterly tranquility of his early works and examines the keenly-felt tension, made of coloured and little contrasting surfaces. The movement in his paintings is a simultaneous tug of colliding surfaces.

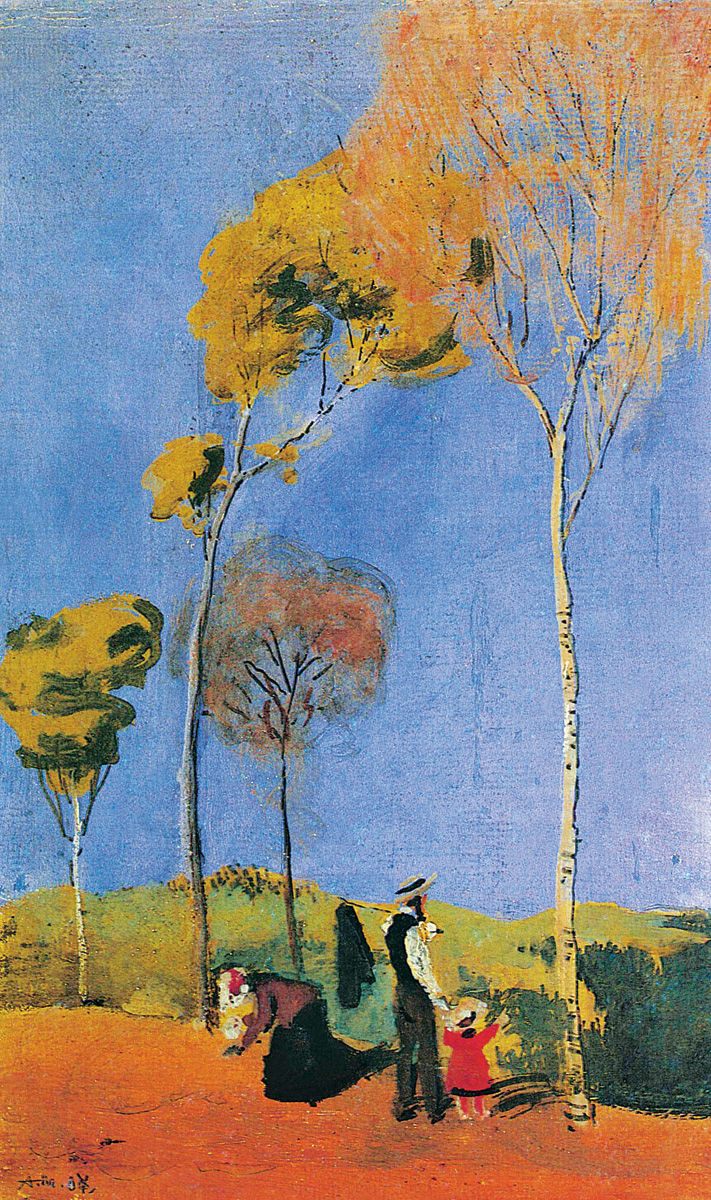

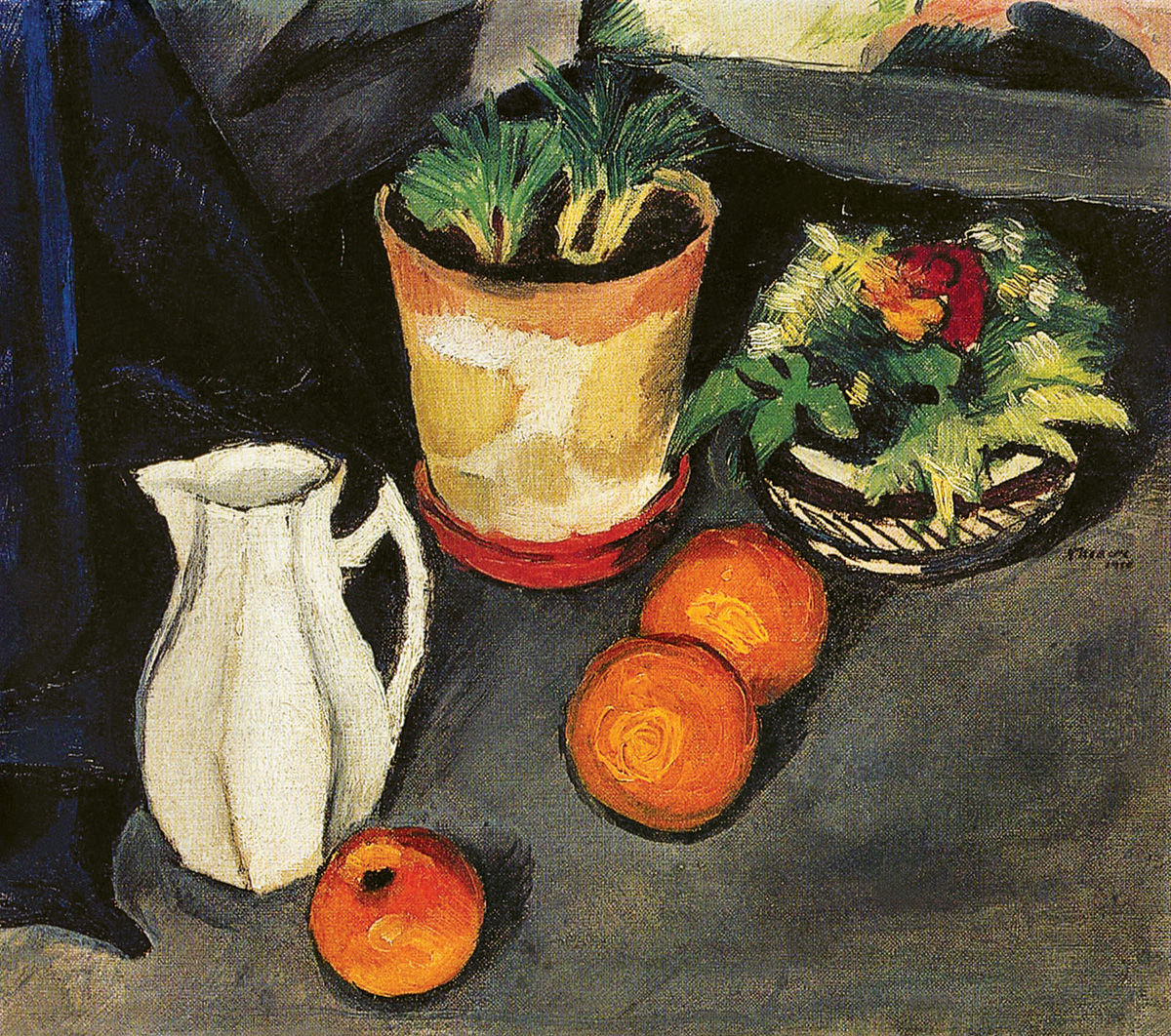

Portrait with Apples (Portrait of the Painter’s Wife), 1909

Oil on canvas, 66 x 59.5 cm. Lenbachhaus, Munich

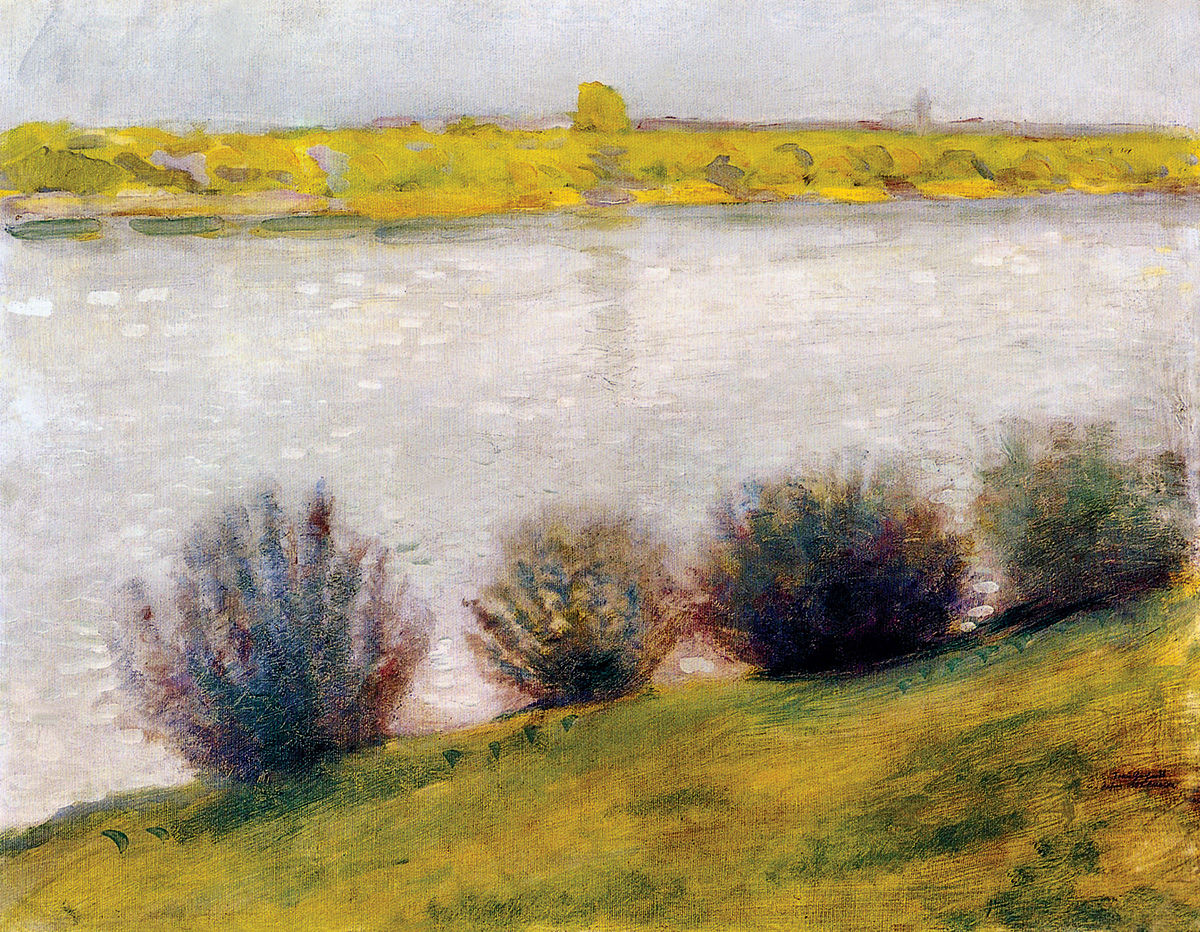

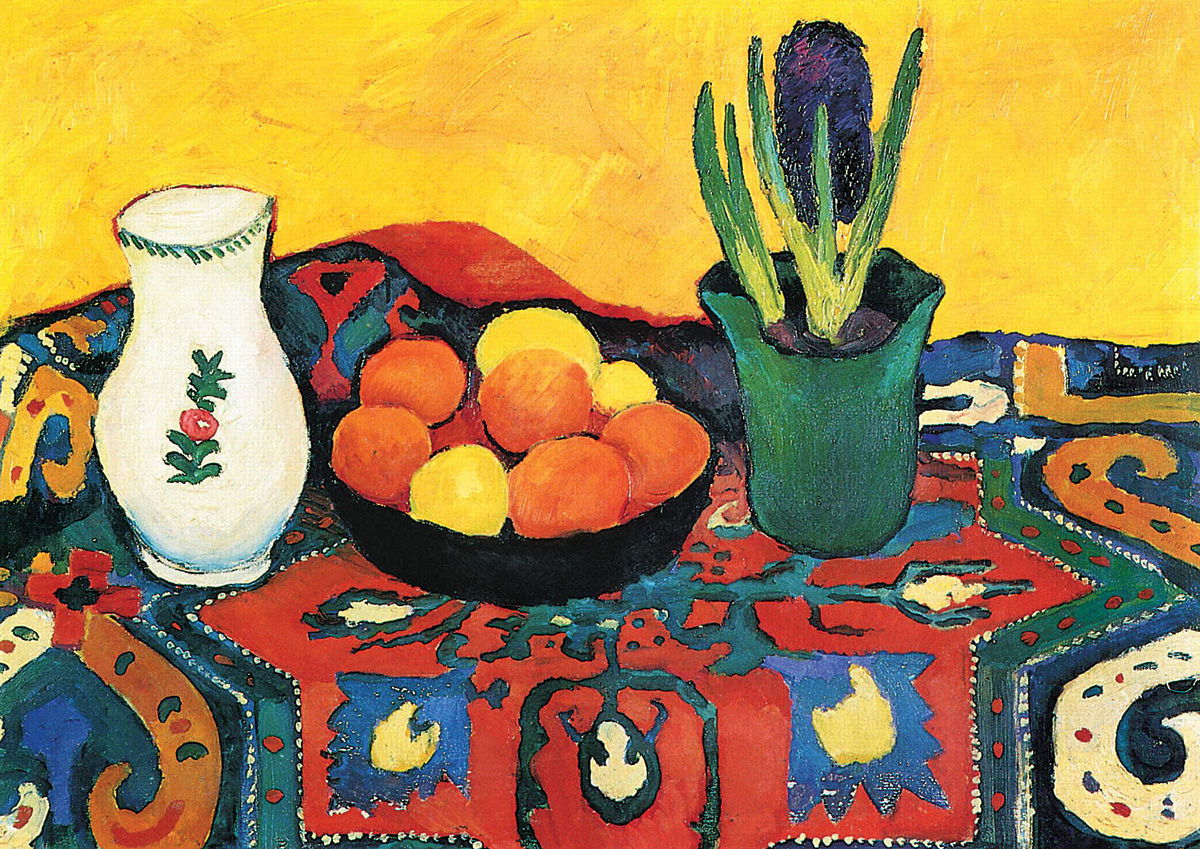

Portrait of the Painter’s Wife with a Hat, 1909

Oil on canvas, 49.7 x 34 cm. LWL-Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Münster

Matisse developed the Impressionist means in his own way to achieve a free expressive creation of the perception of nature. He does not always succeed to give the colour sufficient depth, so colour remains two-dimensional. Delaunay works the colour-contrasting groups in concert without chiaroscuro (or perhaps better, he works them apart, but to one single unit), creating a violent back-and-forth movement in his paintings, a movement which he designed in very realistic images, as well as in works where the movement is an end in itself. He reproduces the movement itself, the Futurists illustrate the movement (like the Japanese illustrate the movement of rain, or the cavemen a running reindeer herd, and Wilhelm Busch the drunken Meyer). Once a Futurist achieves movement in the picture, he has proven his worth as an artist.

Incidentally, one is also inclined to allocate from some old pictures all that is sanctimonious, pathetic, feudal, or cozy as illustrative additions, under which the simple living composition suffers when the artist takes a greater interest in the illustrative aspect. There are many instances across several paintings of the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries, which are inaccurate and superficial. The people’s aesthetic perception of the arts has changed, and this has actually happened very quickly. Since when has Egyptian, early Greek, early Christian and Romanesque painters, Chinese, and exotic art been considered truly great art? Not long ago, we all had good reasons to explain why they could not do better. However, in order to be immune to any accusations of my enjoying primitives, I will confess that I exceedingly love Giotto, the Sienese, the Cologne masters, the early Flemish school of Ferrara, the Dutch still-life painters, Manet, Renoir, and many others, in whom I see the sensitivity of the “spirited”. The lively does not necessarily need to coincide with the imitation of nature. I believe that not many “art lovers” share the view that Privy Counsillor Bode recently expressed in an attack on the “new art”: Art is imitation of nature. It was thanks to the urge for living expression that Gothic churches were built, Mozart’s sonatas were produced, and also African dances including the corresponding masks created without the permission of the art critic. And so it will, I think, remain for a long time.

August Macke

The Masks by August Macke

A sunny day, a cloudy day, a Persian pier, a sacred vessel, a pagan idol and an immortelles, a Gothic church and a Chinese junk ship, the bow of a pirate ship, the word pirate and the word holy, dark, night, spring, cymbals and their sound and the shooting of the ironclads, the Egyptian Sphinx, and the beauty mark on the cheeks of the Parisian courtesan.

Ibsen and Maeterlinck’s lamp light, the village road and ruin painting, mystery dramas during the Middle Ages and the scaremongering of children, a landscape by Van Gogh and a still life by Cézanne, the whir of the propellers and the neighing of horses, the jingoistic cries of a cavalry attack and the war ornament of the Indians, the cello and the bell, the shrill whistle of the locomotive and the dome-like shape of the beech forest, Japanese and Greek masks and stages, and the mysterious, muffled drum sound of Indian fakirs.

Is life not worth more than food and the body more than clothing?

Incredible ideas manifest themselves in tangible forms. Tangible by our senses in the form of a star, thunder, a flower, etc.

Form is a mystery to us, because it is the expression of mysterious forces. They are vital for knowing the secret powers, the “invisible God”.

The senses for us are the bridge from the unfathomable to the tangible.

Showing the plants and animals means feeling their secret.

Hearing the thunder is feeling its secret.

Understanding the language of forms means to be closer to the secret, living.

Creating the forms means living. Are children not creators who draw directly from the secret of their feelings, more than the imitators of Greek forms? The “savage” artists who have their own forms, are they not as strong as the shape of thunder? The thunder expresses itself, as does the flower; each force manifests itself as a form. And so does the human being. Something is driving him to find the words for concepts, the evident from the unclear, conscious from unconscious. This is his life, his creation.

Like human beings, forms change and develop anew.

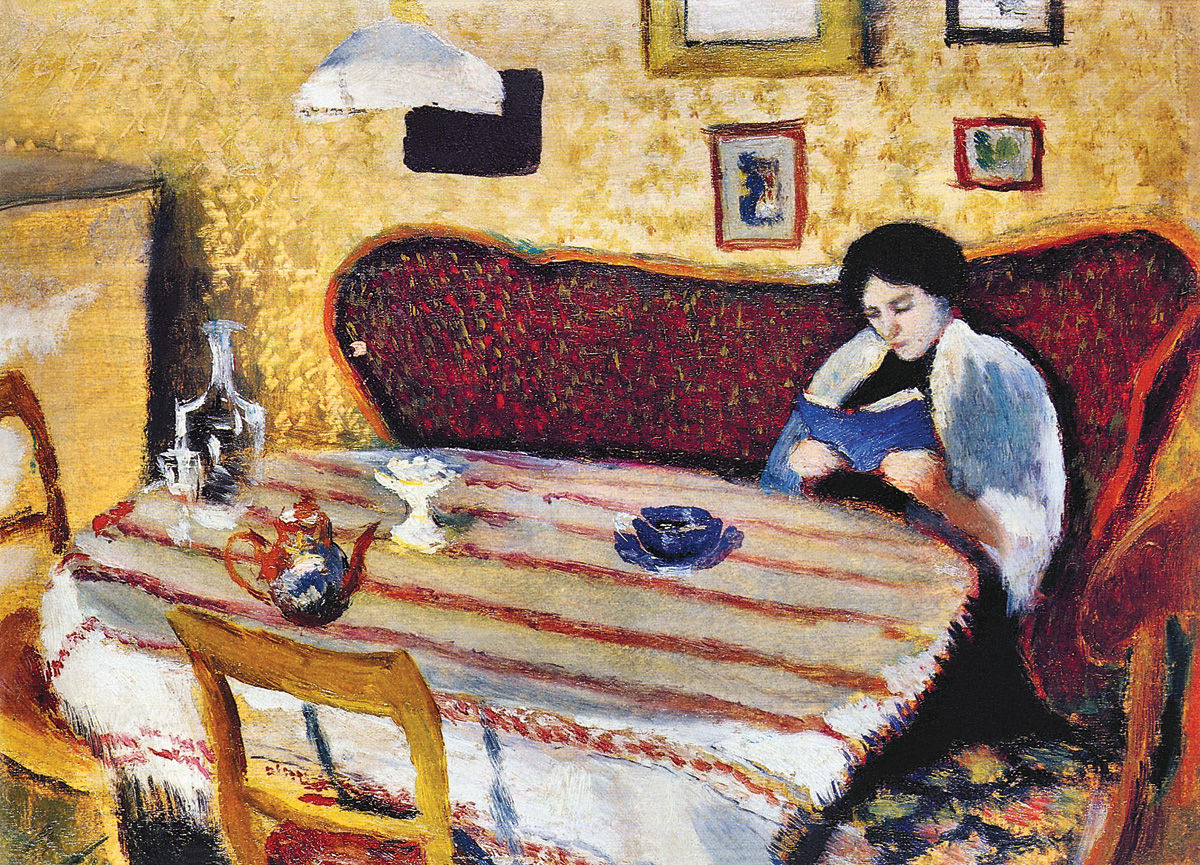

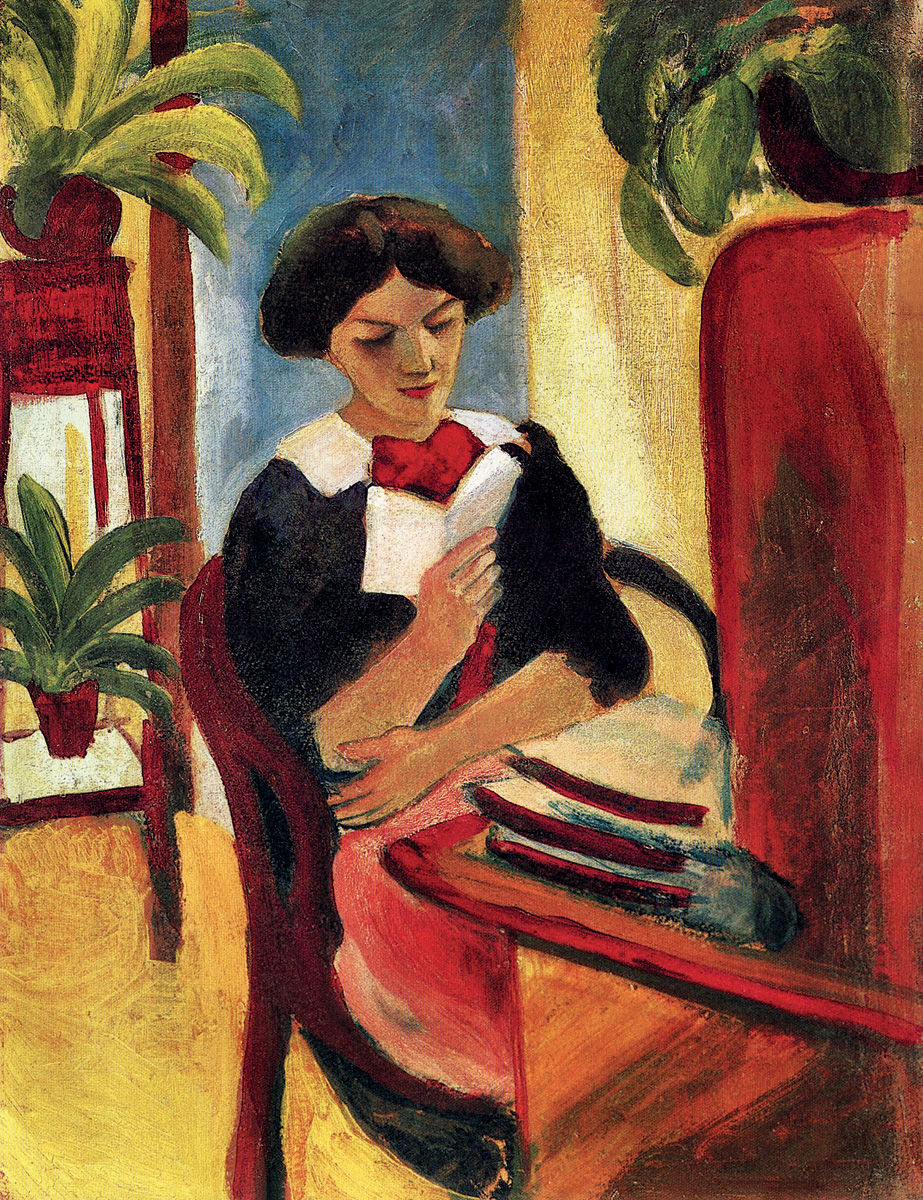

Women Reading at the Table (Elisabeth and Sofie Gerhardt), 1910

Oil on canvas on cardboard, 64.5 x 58 cm. Private collection

Blue only becomes visible via red, the size of the tree via the smallness of the butterfly, the youth of the child via the age of the old man. One and two is three. The formless, the infinite, the zero remains unfathomable. Man expresses his life in forms. Any form of art is an expression of his inner life. The exterior of the art form is its interior. Every genuine art form is a manifestation of our inner life. The outside of the art form is its inside. Each authentic art form emerges from a reciprocal interrelation of man and the factual materials of the forms of nature, of the art forms. The scent of the flower, the happy jumping of the dog, the dancer, the wearing of jewellery, the temple, the image, the style, the life of a people, and a cultural era.

The flower opens when dawn creeps in. The panther ducks down at the sight of its prey, and his power grows as a result of his view. And from the tension of his strength results the scope of his jump. An art form, a style, emerges from a tension.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Impressionists found a direct connection to this natural phenomena. They created a new style, with the intent of representing the organic natural form of light, in the atmosphere; that was their slogan, which changed in the course of time and in their work.

The Impressionists drew their artistic inspiration from art forms of the farmers, from the “primitive” Italians, the Dutch, the Japanese, and the Tahitians. They were all inspirations like the natural forms themselves. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Paul Signac (1863-1935), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898), Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), or even Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) are as far removed from Naturalists as El Greco (1541-1614) and Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337).

Their works are not only the expression of their inner life, they are also the form of their souls in the material of painting. It does not necessarily suggest the presence of a culture; a culture that would be as similar for us as the Middle Ages, the Gothic culture in which everything has a form, a form born only out of our lives. Strong and natural like the scent of a flower.

Elisabeth at her Desk (Elisabeth Reading), 1911

Oil on cardboard, 49.5 x 37.9 cm. Museum Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern

We have forms, in our complicated and confusing time, that will touch everybody’s heart as much as an African fire dance or the mysterious drums of the Indian fakirs. The philosopher stands as a soldier next to the farmer’s son. Both grabbed up by a parade, whether they like it or not. At the cinema, a professor watches the film alongside a saleswoman, at the theatre the ballerina charms the most loving couples as strongly as the solemn tone of the organ in a Gothic Cathedral will move believers and nonbelievers.

Forms are strong expressions of talented life. The difference amongst these expressions consists in sound, word, colour, and materials such as wood, stone, or metal. However, it is not necessary to understand every form, because after all, not every language in the world is understood by everyone either. Artists and apparent art connoisseurs previously relegated all art forms of the so-called primitive peoples to the area of Ethnological arts or arts and crafts with a dismissive wave of the hand; this is, at the least, surprising.

What you hang as a picture on the wall is something, in principle, which is similar to the carved and painted pillars in an African hut. For the African, his idol is the tangible form of an unconceivable notion, the personification of an abstract concept. For us, the image is the tangible form of the vague, intangible idea of a deceased person, a plant, an animal, and of all the magic of nature, of life’s rhythm.

Does Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890, Musée d’Orsay) not originate from a similar intellectual life as the amazed grimacing face of a Japanese juggler on a woodblock print? The mask of the disease-causing demon from Sri Lanka is the horror gesture of a natural people, with which the priests conjure up sickness. For the grotesque ornamental artifice of masks we can find analogies in the monuments of the Gothic and also in the buildings and inscriptions in the Mexican jungle. The significance of the dead flowers in the portrait of the European doctor are the emaciated corpses for the mask of the conjurors of malady.

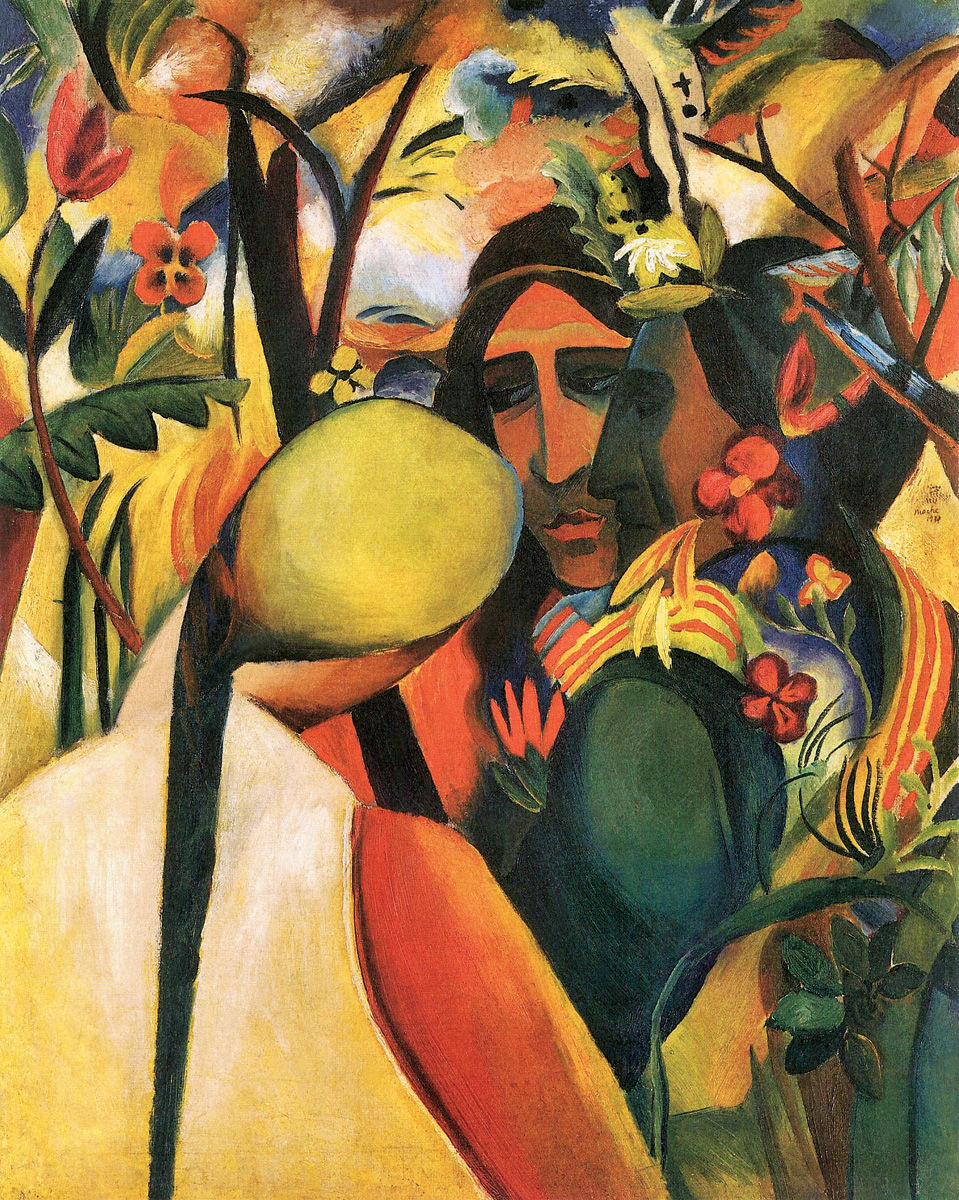

Indian Riding a Horse, 1911

Oil on wood, 44 x 60 cm. Bernhard Koehler Collection, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich

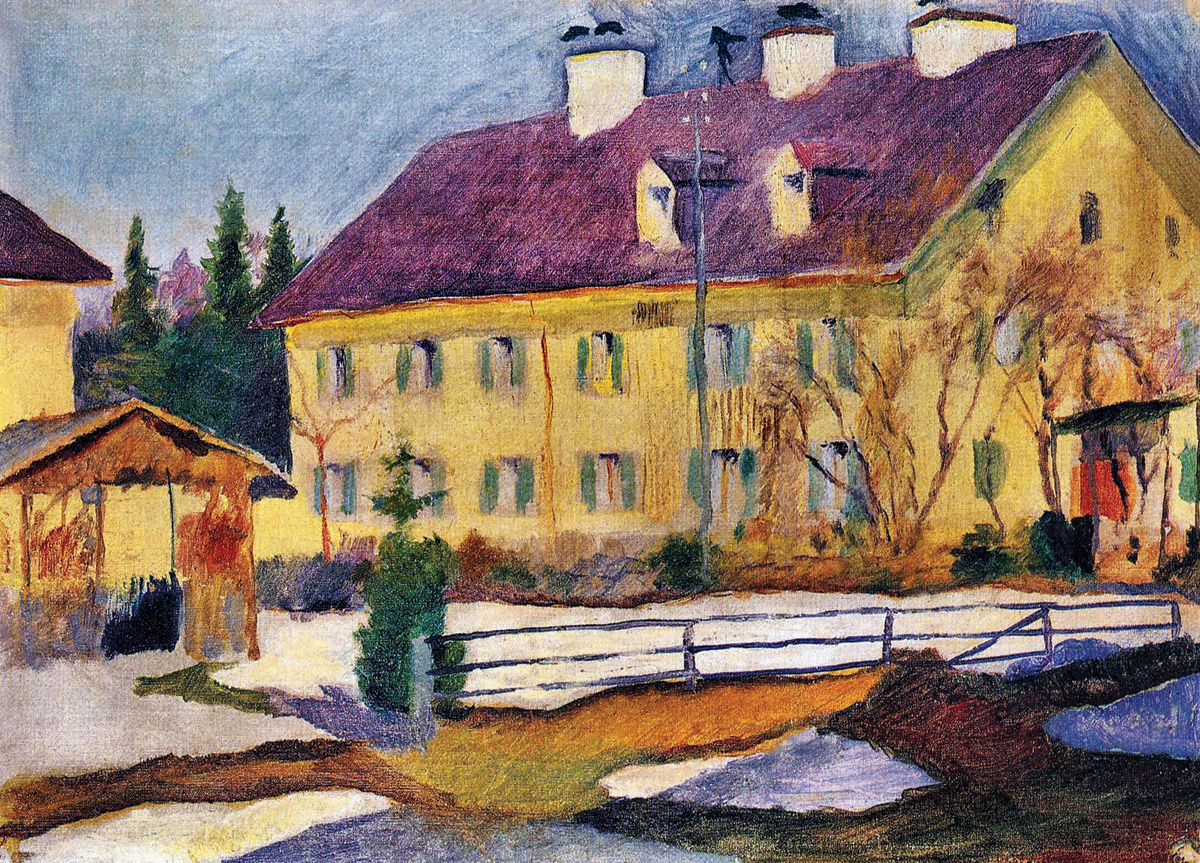

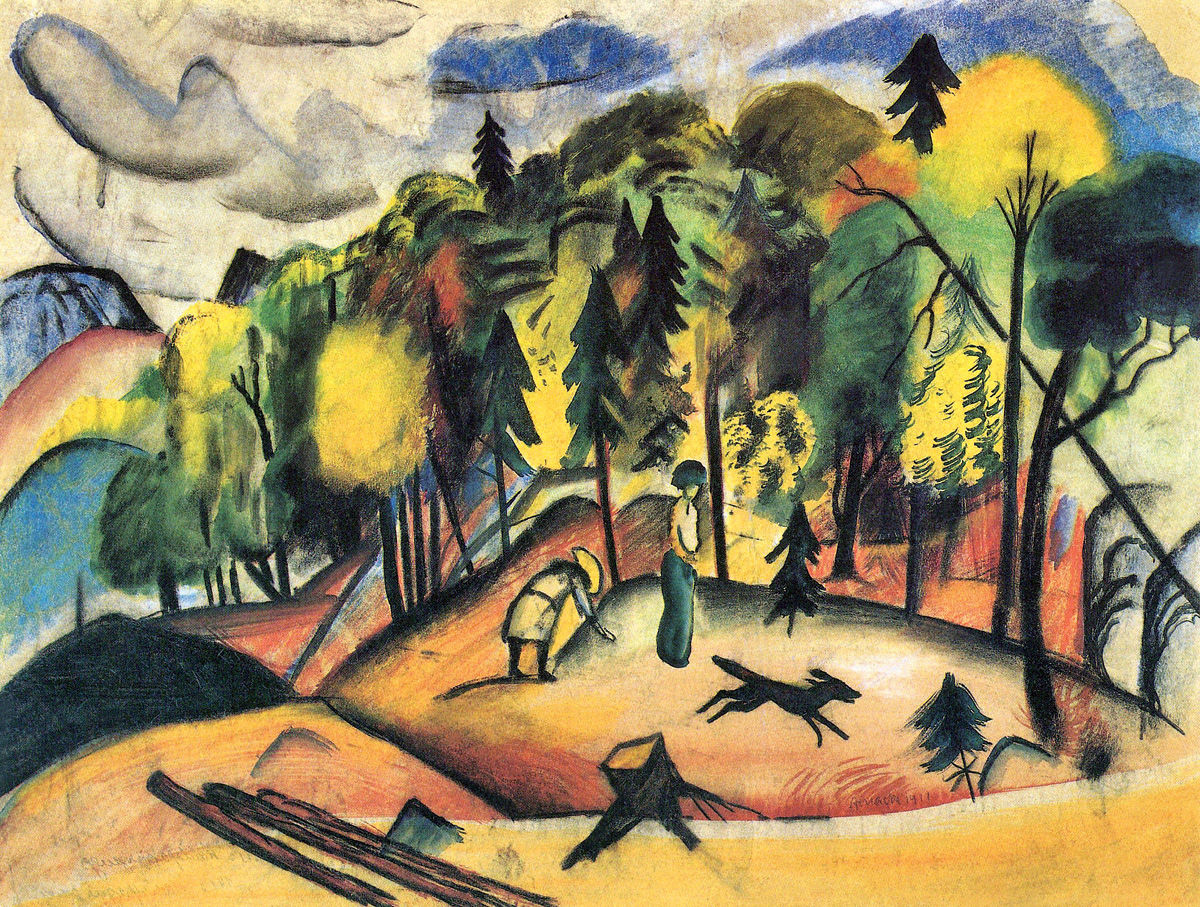

The Macke’s Garden in Bonn, 1911

Oil on canvas, 70 x 88 cm. Westfälische Landesbank AG, Girozentrale, Düsseldorf

The bronze casts of the inhabitants of Benin (West Africa), discovered not until 1889, the idols of the Easter Islands in the Pacific Ocean, the collar of the chief from Alaska, and the wooden mask from New Caledonia speak the same strong language as the Chimeras on the Paris Notre-Dame Cathedral and the grave stone in Frankfurt Cathedral. As if to mock European aesthetics, forms speak a sublime language everywhere, and as early as in children’s play, through the hat of a model, and in the joy of a sunny day, materialise inwardly invisible ideas.

They reflect the joys and sorrows of people; therefore, people are behind the images, the cathedrals, the temples and masks, behind the inscriptions, the musical works, the show pieces, and dances. Where they are not behind it, where forms are empty or causeless, no art can exist.

Styles can also come to an end by inbreeding. The intersection of two styles will create a third, new style. The renaissance of the ancient world, the disciples of Schongauer, Mantegna, and Dürer. Europe and the Orient.

The Impressionists found the direct connection to the natural phenomena. The representation of organic nature in the form of light, in the atmosphere, was their shibboleth. It changed under their hands. The art forms of farmers, the primitive Italians, the Dutch, the Japanese, and Tahitians became stimulators just like the natural forms themselves. Renoir, Signac, Toulouse-Lautrec, Beardsley, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin. All of them are as little Naturalists as El Greco and Giotto. Their works are the expression of their inner life; they are the form within the artistic souls in the materials of painting. This does not necessarily suggest the presence of a culture, a culture that would be for us what the Gothic was in the Middle Ages, a culture in which everything has a form, born out of our lives, or just out of our lives: naturally, and as strong as the scent of a flower.

The Church of St Mary in Bonn Covered with Snow, 1911

Oil on cardboard, 101.5 x 80 cm. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg

Macke’s Letters to Franz Marc

Bonn, after 9 December 1910

Tagernsee [crossed out]

After our request, our friend Job played the three corresponding sounds on the piano for me, well, she claimed to play the same important role in music. So: Blue, Yellow, Red – parallel phenomena: sad, happy, brutal (in tones as well as in colours).

All the lines (or melody) determine the sequence of the colours (or sounds). Ascending and descending melodies that are in full integration. The descending parts may already be included in the ascending ones and vice versa. The colour complex led by means of lines (melodies) is the question to the answer of the countercomplex. (Signac is a very freelance musician of colours).

Light and dark is an essential element of the melodic direction, as well as yellow, purple, orange, blue, green, and red. This explains the longing for pure sounds without grey and mishmashed colours.

The boundaries of yellow, red, and blue blend into orange, violet, and green, whereby the fact of getting lighter corresponds to the gradual ascent of the piano sounds, the composition of the octaves of the piano (I believe there are eight of them) corresponds to the number of concentric circles. Further merging of neighbouring colours results in blue-green, blue-red, except blue (i.e. hot and cold blue), yellow-red, blue-red except red, etc.

The composition associated with these means now has to happen at an “indeterminate hour from a still hidden source at this time“, joyful, painful, and powerful.

I am currently preoccupied by thoughts on Japanese erotic pages, by Giotto, Michelangelo, but also preoccupied by the horses that are painted in Sindelsdorf. I daily enjoy your horses and bears. My goodness, if only I could paint love like the Renaissance people have painted suffering! I study the forms of suffering in order to learn it. In general, the idea of cavalry battle, or infanticide, or the Rape of the Sabines is divine. People interiorised so much and that explains their great art. Today you go into the “interior” of subways and coffee houses. The painters, however, escape into solitude and work on themselves. This may not be contemporary and modern, but useful for the art (I believe).

You can see what state I am in.

You, Spaniard! Let me gently tell you something. Bonn is a real city of pensioners. Everything is very quiet, respectable, and unremarkably unobtrusive. The area in which we live, has much to offer. Hounds, riders, and equestriennes, children who have a go at each other. Then, around you, the houses look at you with living eyes. I am extraordinarily fond of this part of the city. Furthermore, we have a provincial museum with magnificent Roman sculptures, mosaics, gold, and stone jewellery, in front of which you would be lying on your knees and praying like a Roman emperor. Then, magnificent “old Dutch”, old Italians, two Velázquez, absolutely everything you need. The museum is wonderfully bright and modern. The directorial assistant Dr Cohen, a friendly, hard of hearing enthusiast of contemporary art, has gained a reputation that suits me just right. He told me that he had sent a photo of Nauen’s large work to Helmuth. Probably as regards to the “Neue Künstlervereinigung München“ (Munich New Artist’s Association). I concern myself again a great deal in theory, I have fabricated a colour ring for myself. I think it is very important to get to the bottom of all the rules of painting, especially in order to link the modern to the ancient. Please give me your thoughts about the following items that I collect, and for which I would like you to look for something new and let me know. Maybe it’s not new to you. My intuition says it is three colours: Blue, Yellow, Red.

So, farewell now. I am happy when you are working. Give us animals that we can admire for a long time. May the hoofbeats of your horses reverberate to the most distant ages. Therefore, shoe them well. Please write to me soon.

Greetings to Ms Franck, Niestlé, Legros, and yourself.

Your August Macke