Strategizing is a fundamental part of a leader’s job. The question is, is the strategy drawn based on the leadership team’s assumptions and beliefs or is it fleshed out by looking at real data and problems and with the input of the rest of the organization? Does this strategy outline actionable improvements that have a clear correlation to the achievement of business goals? Do people understand what their contribution to those goals is?

If you are trying to answer these questions, then strategy deployment (Hoshin Kanri, if you are after the Japanese term) is the right approach for you.

According to the Lean Lexicon, Hoshin Kanri is “a management process that aligns – both vertically and horizontally – an organization’s functions and activities with its strategic objectives. A specific plan – typically annual – is developed with precise goals, actions, timelines, responsibilities, and measures.”

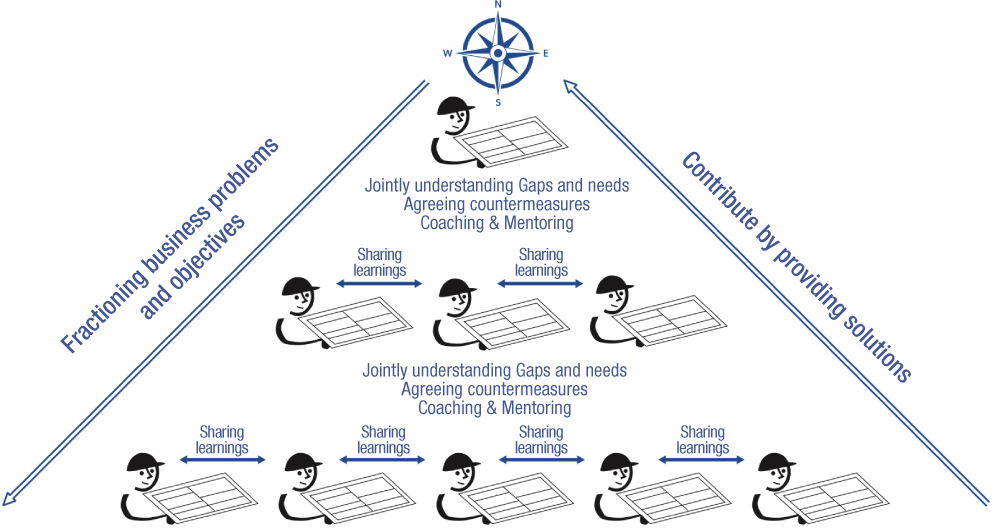

The Lexicon continues by explaining how Hoshin often starts as a top-down process as the Lean Transformation is initiated. “However, once the major goals are set, it should become a top-down and bottom-up process involving a dialogue between senior managers and project teams about the resources and time both available and needed to achieve the targets. This dialogue often is called catchball (or nemawashi) as ideas are tossed back and forth like a ball.”

One of the primary goals of Hoshin Kanri is to identify those projects that are necessary but also achievable, those that will engage people from across functions and create change, the positive effects of which will be felt throughout the company.

Over time, as the Lean Transformation progresses and the company becomes more familiar with the process, Hoshin “should become much more bottom-top-bottom, with each part of the organization proposing actions to senior management to improve performance.”

In his Planet Lean article 10 Strategy Problems Hoshin Kanri Can Solve, Flavio Picchi, President of Lean Institute Brasil, wrote: “Hoshin aligns leadership horizontally and vertically, connecting problem solving and improvement initiatives at different levels of the firm with organizational goals, thus avoiding dispersed efforts.”

Hoshin Kanri effectively takes the work of management (in this case, strategizing and deploying the strategy) and breaks it down into bits to ensure it is easy to define, track, and complete.

In the Planet Lean article Through Hardship to the Stars, Vicenç Martínez Ibañez and Antoni Campos Rubiño of Hospital Vall d’Hebron in Barcelona, say: “Hoshin is where strategic planning and daily operations come together. The KPIs you track with it are used to evaluate the effectiveness of the plans you are deploying and to ensure that weekly, monthly and yearly we are working as we should. Hoshin reflects a fundamental change that took place in the organizational culture. These days, it is organizational objectives that come down from hospital management – not directions. At the lower level of the organization, people know exactly what they have to do to meet the targets that will collectively contribute to the achievement of those hospital-wide goals.”

This powerful management practice allows you to focus on what’s truly important for the success of the business (True North) and to transform the company’s goals into actionable items that people at different levels can tackle. This, in turn, defines their roles and helps them to see their contribution to the success of the business. This is why it is also a great way to foster engagement.

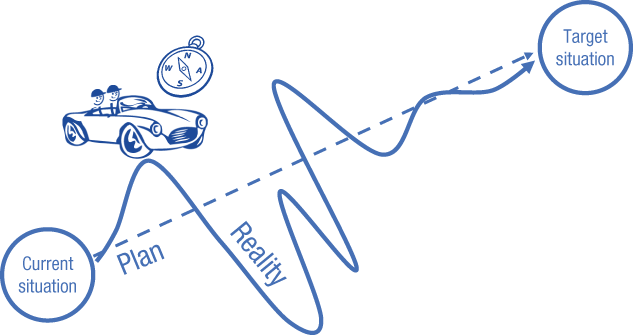

One of the things making Hoshin quite challenging is the fact that management typically suffers short-termism, whereas this practice (much like Lean Thinking itself) works best when a clear, long-term purpose is defined and communicated to everyone in the organization. As you develop your Hoshin, it is advisable to frame your plan for the next year (for example) within the context of your long-term mission. True North cannot be reached in the short term. However, if we understand how to fully leverage it, Hoshin Kanri can represent a powerful tool that helps us to organize our thinking and activities and to identify the steps we need to take to get to our destination.

To summarize, with Hoshin Kanri we gain visibility of the direction we want the business to move towards and deploy that vision to the rest of the organization. This activity has to be tied to management, to ensure the deployment takes place according to the plan.

Hoshin Kanri allows us to define a strategic plan that is aligned with the organizational work given a certain target, and to adapt that plan as circumstances around us change. It’s a system of deployment and alignment. It gives us a way to understand at any moment whether or not we are meeting our strategic goals.

People often tell me they wish they had started their Lean Transformation with Hoshin Kanri. This is hardly surprising, because Hoshin has the power to connect the dots, so to speak, and create an alignment across the organization that is rarely achieved in more traditional, non-Lean settings. However, people say this in hindsight, after they have started working with Hoshin. Truth is, when setting out on a transformation, a certain degree of instability in the process helps Lean to take root. Painful business problems that get solved are the best way to “sell” Lean Thinking to value creators up and down the company. In other words, you need something of a Lean foundation for Hoshin to work effectively.

Once you are ready for Hoshin, however, how do you make it happen? What does the Hoshin method entail? I’ll now outline the steps necessary to set up a functioning Hoshin Kanri process.

• Identify the number of levels in the organization, the layers of the business – management units, we could call them – from front line to top management. This includes cells, areas, departments, teams, and so on. At this stage, you are striving to understand the cross-section of the business, the “parts” that it is made up of. While this ultimately depends on the complexity of the business, you can usually identify three macro-layers: front-line workers (like operators, nurses or administrative staff), middle management (conjunctions of units or departments) and top management.

• For the top level (which is where the work carried out across the organization connects with the business strategy and P&L):

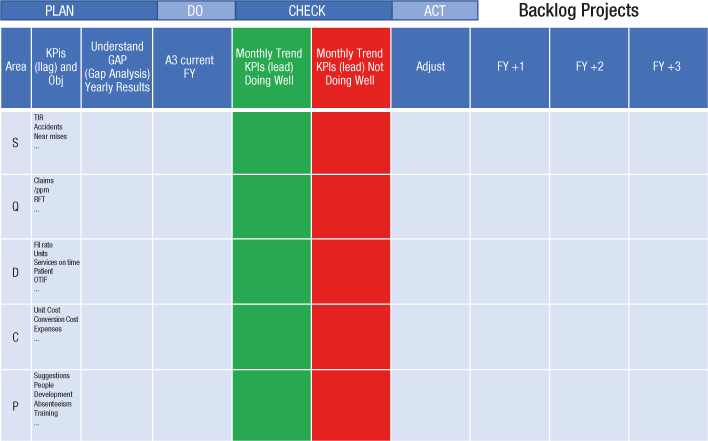

– Definition of strategic areas (macro objectives on which the success of the business depends). Companies typically use SQDCP (Safety-Quality-Delivery-Cost-People), but business priorities don’t always fit strictly into this categorization – for example, “becoming the number one supplier in the market” or “having the best professionals in the industry”. It’s important, therefore, to clearly define your strategic areas before you start off with Hoshin.

– Identification of the KPIs tied to each strategic area. What defines and measures success for each of the strategic objectives we identified?

– “Distillation” of KPIs, focusing on lag indicators. Very often, people identify a very long list of KPIs, which needs to be narrowed down. What we do with teams is following something we call the “Eurovision method”: just like in the Eurovision Song Contest, countries vote for their favorite song, so teams in this distillation exercise are asked to vote to select the KPIs they want to track for each strategic area (SQDCP or else).

– Identification of objectives for each KPI. It’s necessary to assign an objective, unequivocally expressed in figures, for the current year.

– Understanding the gaps. At this stage, if you consider the previous year’s results, you determine how close or how far you are to/from the objectives you set for yourselves.

– Establishing corrective actions, in accordance with the reality revealed by the Value Stream Map, by opening high-level (strategic) A3s.

– Tracking indicators and adjusting as needed. Every month, you monitor the indicators and act whenever results aren’t as expected.

– Standardization of the reviewing process. At a high level, this means establishing the rules of the game for the reviews happening weekly, monthly, etc. (in other words, the governance).

• Deployment to lower levels:

– Define lead KPIs that will deliver lag KPIs at top level. What does each department need to deliver in order to contribute to the organization-wide objective? There has to be a clear correlation between lead and lag KPIs.

– Identify gaps.

– Identify the A3s we need to open. These are lower-level A3s (department A3s) that are, much like the lag and lead KPIs, connected to the strategic A3s at top level.

– Define frequency of measuring and review process. This should be in sync with top level reviews.

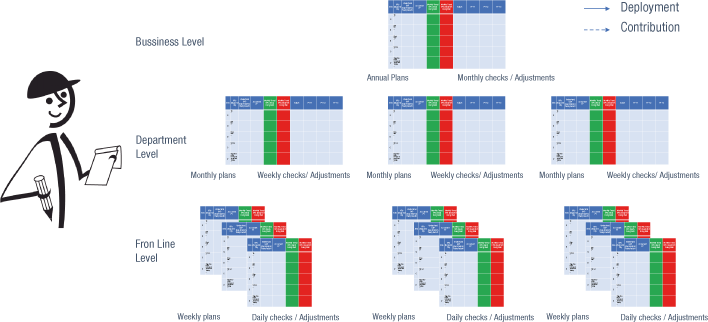

The big strategic issues that make up your Hoshin plan need to be broken down into smaller problems to be solved at lower levels of the organization, and the key tool for the resolution of such problems is A3 Thinking. This means deploying strategic goals from the top down, translating them into goals specific to each and every individual or function within the business, so that, in response, they will come up with the necessary solutions. This isn’t to say that indicators have to be the same at top level and front line, but that there needs to be a lag-lead relation between them. For example, the consolidated costs in an organization can be divided into different areas of the Hoshin plan. By managing their costs, each area will contribute to the global objective.

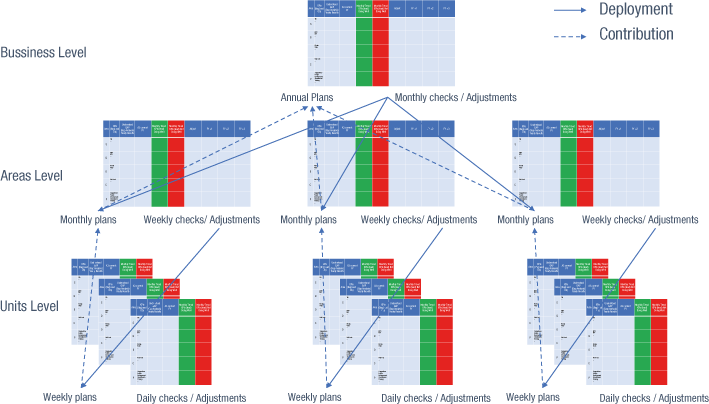

Similarly, tracking KPIs doesn’t happen at the same frequency across levels. At top level, indicators are typically followed up monthly, while at the front line weekly or even daily follow-up might be necessary (depending on the indicator).

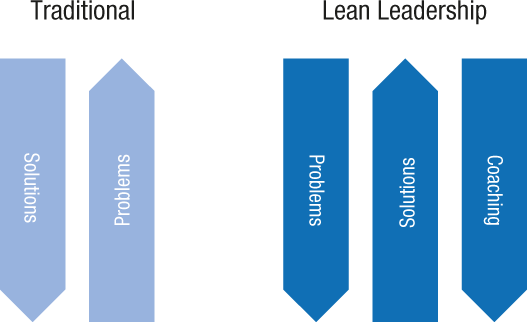

In traditional organizations, solutions go from the top down, which results in low levels of engagement. When solutions are imposed from above, people tend to reject and resist them. Conversely, in Lean organizations leaders ensure that people understand the challenges they are facing so that they can come up with best possible solutions – and they will coach them along the way. This facilitating role of the leader in the negotiation of solutions is known as catchball, or “nemawashi”, which is key to the success of any Lean Transformation.

According to the Lean Lexicon, nemawashi is “the process of gaining acceptance and preapproval for a proposal by evaluating first the idea and then the plan with management and stakeholders to get input, anticipate resistance, and align the proposed change with other perspectives and priorities in the organization. Formal approval comes in a meeting to sign off on the final version of the proposal. The term literally means ‘preparing the ground for planting’ in Japanese.” This concept lies at the heart of Hoshin Kanri.

The recommended structure of indicators is SQDCP – Safety, Quality, Delivery, Cost, People. This framework makes it easy to assign priorities to the business problems that might appear, preventing us from having to deal with hundreds of issues at once.

Most businesses focus on cutting costs to improve their margins or offer a more competitive price to their customers. However, the SQDCP framework forces us to solve problems related to worker safety first. The most obvious reason for this is that nobody wants to work in unsafe conditions, and it is a responsibility of leaders to ensure people can do their job in complete safety. Besides, an unsafe workplace, in which it is hard to know how many employees will be available on any given day due to sick leave or absenteeism, is unlikely to be one in which the work is predictable and, therefore, conducive to good outcomes and/or improvement. Additionally, it will be hard for an organization to keep costs low while having a large number of employees on sick leave at any given time. This is why the SQDCP framework places so much emphasis on safety.

Following safety is quality. If defects reach your customers, it means that they were generated in the first place and, even worse, that you weren’t able to identify them and stop the process in order to address them. Alas, there is no better way of losing customers than delivering to them a product or service that doesn’t meet their requirements or expectations. You can grow sales and expand your portfolio as much as you want, but that won’t matter if quality is not up to par. Only once quality issues have been addressed can you determine whether you are stable and predictable in the volumes of work you have to deliver.

This is also the time to assess how fast and consistent you are in the delivery of a product/service or in the execution of a process. Again, there is no point in trying to reduce cost in a process that doesn’t deliver as expected. Indeed, before we move to the C in SQDCP, we need to ensure we have stabilized Safety, Quality and Delivery. Only then will it be possible to start figuring out how to do more with less. In fact, the improvement in the other three areas will have already contributed to lowering costs.

At this point, where you deliver quality products safely and on time to your customers, you are ready to focus on improving the C. This is when you work to identify and eliminate waste in the process, those non-value-added activities that add time and cost but actually don’t contribute to value generation.

Finally, we have People. The P might be the last letter in the acronym, but that doesn’t mean it’s the least important. In fact, without the contribution and support of your people, you won’t be able to impact any of the other areas of the framework (SQDC). That’s why it’s vital that you don’t forget about the P. It’s common to see how, at first, absenteeism and training are the only indicators tracked. However, as the organization becomes more mature in its understanding of Lean, other elements gradually come into focus, like people and leadership development, motivation, contribution of people to the management system, and so on.

When I worked at Delphi, SQDCP was the framework we followed. Each business unit had a business problem that was linked to one of these five elements. If an area produced many defects, for example, it had a quality business problem. So, the focus was on quality, more than on lead-time or other indicators.

It’s important, however, to ensure that, no matter the methodology you use, you are able to plan but also do, check and act. In the end, the deployment of the strategy can be seen as one big PDCA cycle, as reflected in the structure of the board below.

Our approach to Hoshin (which we developed in partnership with our colleagues at Lean Management Instituut in the Netherlands) was born out of the idea of applying PDCA to every single board making up an organization’s Hoshin. How do you ensure a connection between daily work and weekly work, between weekly and monthly, between monthly and annual? And how do you deploy the annual strategy every month, week and day? Breaking down problems and objectives so that everyone has clarity over what their contribution is to the fulfillment of the business strategy.

At every level of the organization, there has to be a PDCA: a plan (P), monthly or weekly depending on the level we are talking about, related to the “top level” annual plan, actions (D) related to the actions highlighted at top level (this speaks to the relationship between A3s developed at different levels of the business), lead indicators (tied to high-level lag indicators) that allow you to assess where you are (C), and adjustments whenever you are off target (A). This is why the board we developed has a PDCA structure.

Concretely, you take a high-level problem, whose resolution is of strategic importance for the business, and break it down into KPIs, from which you will then generate the gaps you need to address. Monthly, you’ll track the KPIs and adjust when they are not met. This process will be repeated at every level: management, middle management, and front line (for daily accountability).

I recommend A3s as the chief tool for managing this whole process. They are particularly effective when connected with one another across organizational levels (we sometimes refer to this high level/low level relationship as “parent A3s” and “son A3s”). In the long term, you will need A3 Thinking to drive your Hoshin efforts. In fact, every project that is initiated in a business should be handled through an A3 and that’s what you should ultimately strive for. The benefit of systematically using A3s to solve problems is that they establish coach-coachee relationships across the organization and facilitate the development of capabilities. However, when it comes to Hoshin Kanri, the fact that you might not use A3s consistently (which entirely depends on your level of Lean maturity) shouldn’t be considered a limitation.

For many organizations, the introduction of A3 Thinking is one of the first steps in the transformation – in many ways, the A3 acts as an “ice breaker” for the installation of a Lean culture. Having said that, the A3 in itself is not a precondition for the utilization of the Hoshin Kanri process. That is to say, if you don’t use it yet, you can still start with your Hoshin efforts; but if you have it, you are strongly advised to connect it with your strategy deployment. (Many of you will likely have some A3s open, here and there in the business. If that’s the case, create opportunities for as many people in the company as possible to see those A3s and try to spread their use across the organization.)

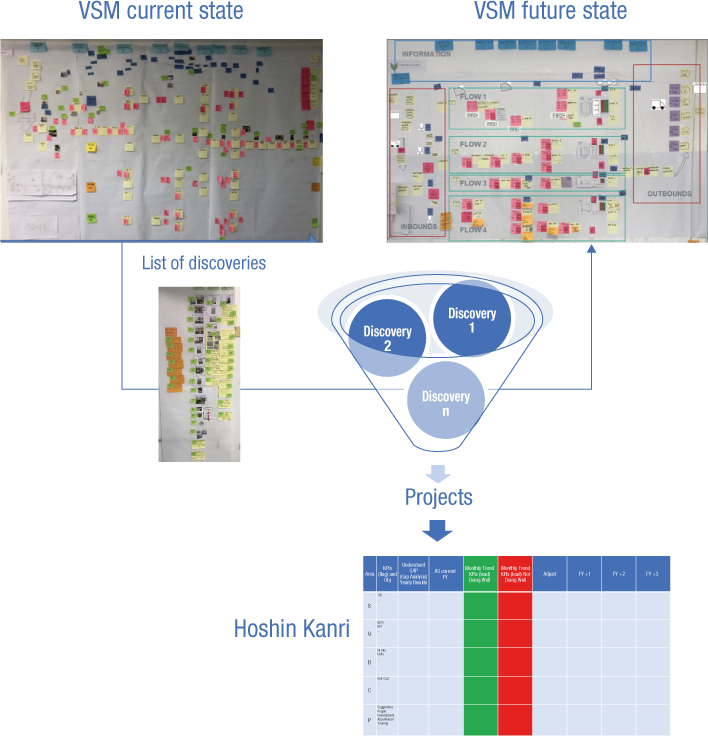

Effectively identifying gaps and launching projects to tackle them is typically a result of a Value Stream Mapping (VSM) exercise – another fundamental piece of the Lean (and Hoshin) puzzle.

VSM is a technical but also a strategic tool, and when the Senior Leadership team uses it they can get an incredibly deep understanding of the reality the business is currently facing. The gemba, which you will need to visit to draw your VSM, gives you an overview of the situation on the ground and helps you to see problems more clearly: when senior leaders start to visit it regularly, practicing genchi genbutsu, they are often surprised by the many epiphanies they have (those “a-ha moments” we often talk about). That’s why it’s so important for leadership to be present at the front line, asking people questions. When you run a VSM exercise as a team, you will find it easier to get agreement on the problems to address – even when there is so much waste that it’s hard to understand where to start (in which case it is useful to group waste into “families of problems” that will then become your projects).

Because it shows all the problems you have in the organization, the VSM can act as an input for Hoshin. It gives you a backlog of projects. This is why the VSM has to be present in the Boardroom: it gives you a plethora of possible projects you can work on, and Hoshin will then help you to select the most critical for you to focus on.

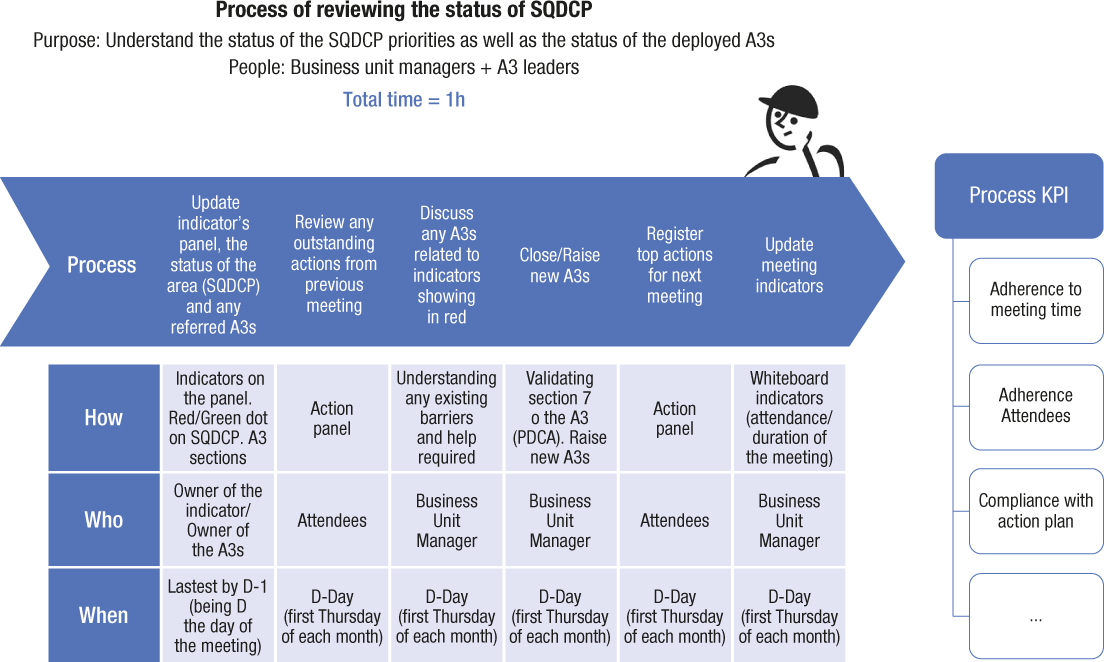

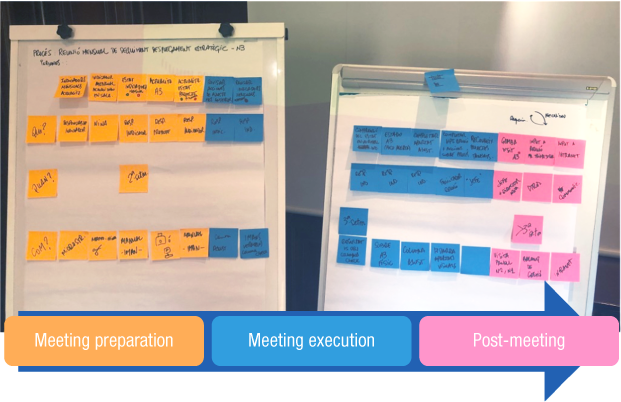

The Hoshin governance process has to be standardized. A3s have to be ready on time, information has to be updated regularly, meetings have to be efficient and stick to the allotted time, and people participating in the meeting need to have done their “homework”.

The definition of a standard for governance gives people a template to follow during each and every meeting, and ensures accountability. You can see a board and use it in any way you want, but there are certain rules of engagement that need to be followed if the process is to unfold the way it’s supposed to. Just like you can’t play Monopoly with a different rulebook for each player, so there has to be one way for each individual to participate in the Hoshin meeting and interact with the board. This standard will tell you the who, when, how for each section of the board. For example, who has to update a certain piece of information? How often? Using what tool? This is vital, because it creates the rules of the game. As we will see in the examples at the end of the book, this means engaging in a real development effort to teach people how to participate in the meetings.

But how do we ensure the meetings happen when and as they should? That the right things are discussed? That people do the proper preparation? To be sure the review process is healthy and the meetings are following the defined standard, we should set some KPIs to track. Common ones include: level of participation, duration of the meeting, and adherence to the established order of topics.

Put in simple terms, a board is not a board if there is no management process behind it (what we refer to as “the Arrow”, as we will see in the next chapter). This highlights the importance of another piece of our six-element model – leader standard work – which will dive into in a few pages.

• Strategy deployment is key to allowing an organization to understand “what is important” and separate it from “what is urgent”. The Hoshin mechanism ensures that you address the important things, even in the midst of all the fire-fighting that happens on a daily basis as urgent problems appear all around you.

• Strategy deployment allows you to communicate the strategy in a language the whole organization understands. This means it makes it possible to involve everyone in the transformation of the business.

• There can be no contribution by people without a clear understanding of the company’s strategies and the proper deployment of gaps to be addressed.

• In your Hoshin Kanri implementation, always follow the PDCA structure. And remember: it is not only P or D; it is also about C and A!

• Make your Hoshin communication as visual as possible.

• When it comes to KPIs, “less is more”. Select your lag KPIs and let the downstream boards track the lead ones. Don’t try to follow everything at a top level. Each level should manage its “own business”.

• Make sure that you involve the right people in the Hoshin exercise. They need to represent the entire organization.

• When defining your KPIs, if necessary, combine your strategic objectives with the SQDCP framework.

• Pursue main strategic projects – not many projects – by having PDCA guides you through the selection process. Projects don’t have to be many, but they do need to be the right ones.

• Make sure that the reality on the ground matches the plans devised as part of the strategy.

• Implement the right adjustments as the strategy is deployed through the organization and you move closer to True North.

• Don’t shy away from adapting your strategy to quick and unexpected changes in circumstances in the outside world. As we all know, the last few years have been particularly turbulent: during the pandemic, for instance, many organizations were forced to make important adjustments to their strategy. While Hoshin is typically an annual activity, to have management in tune with the situation on the ground allows companies to change course “on the go” and to think more about the short term when the situation calls for it.

Now it’s time for you to try and build your own boards.

1. Identify your strategy for the next few years and make an exercise of selecting a set of KPIs related to it and of goals, year by year.

2. Draw a draft of your “architecture” of boards (top level, department level, front-line level). How many do you have?

3. “Distil” the KPIs that you will eventually use in each area (SQDCP).

4. Build your Hoshin PDCA board for top management:

a. Plan: this year, at the organizational-level board, what annual Gaps do you need to focus on?

b. Do: what strategic A3s do you need to open this year?

c. Check: put your trend in a monthly graph. How are you doing against KPIs? Are you in the light grey or in the dark grey?

d. Act. What do you need to adjust in different improvement projects or trends?

5. Define a governance process and start using it.

6. Learn and adjust based on the experience you are gaining.

7. Go to your departamental boards and repeat steps 4, 5, and 6. You’ll later do the same for the front-line level.