Introduction

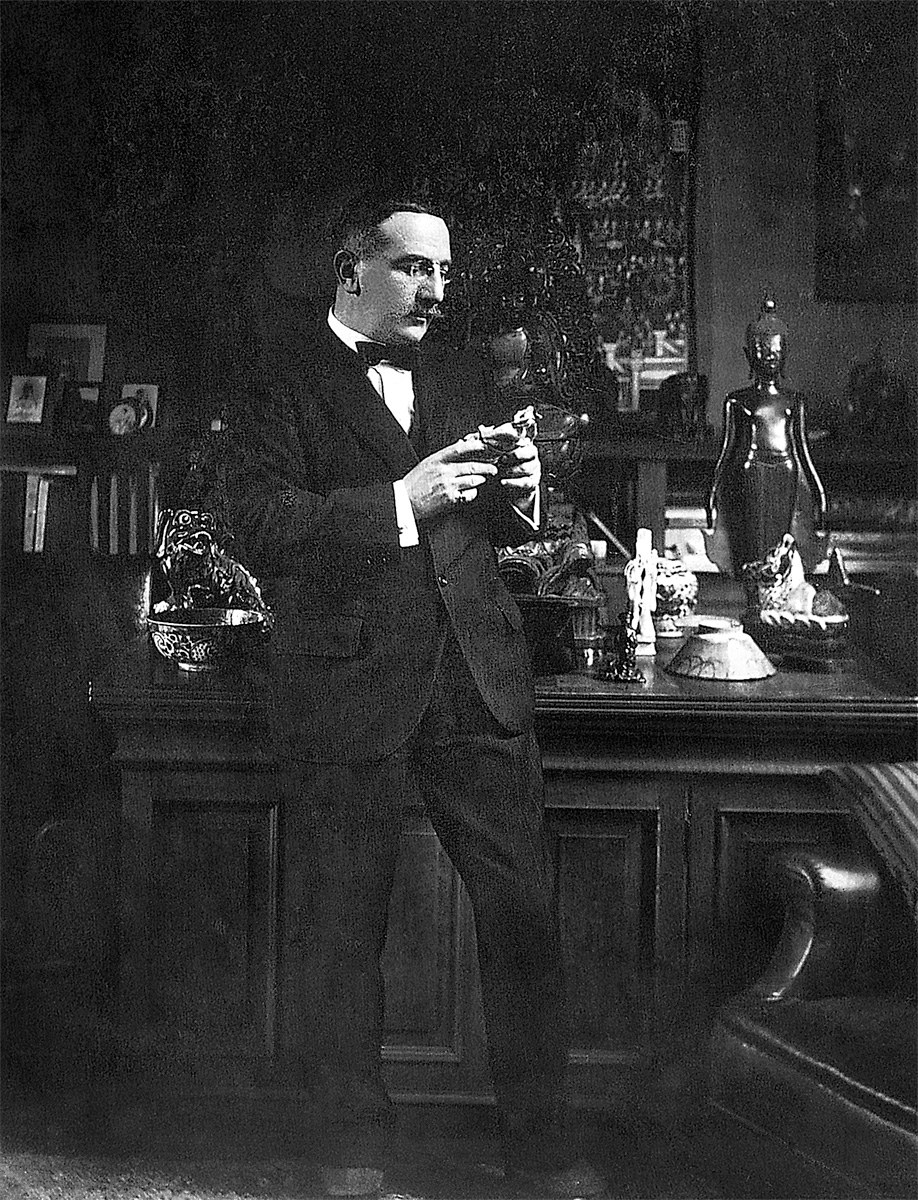

‘A marvellously decorative artist with great taste, infinite imagination, extraordinarily refined and aristocratic’ - this is how his friend and colleague Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva saw Léon Bakst [1]. A leading player in the cultural ferment boiling up in Russia at the turn of the century, Bakst, together with his close colleague Alexander Benois, revolutionized the concept of theatrical design and was a major element in the huge explosion of talent fostered and directed by the extraordinary Sergei Diaghilev [2].

Diaghilev's World of Art group was a focal point for the most inspiring work of the early years of the 20th century. It is fair to say that its exhibitions were responsible to a great extent for pushing the aesthetic perceptions of Russian culture on to a new path. And one of those who made a major contribution to this new direction was the quiet, shy, poverty-stricken Lev Rosenberg, known to the world as Léon Bakst [3].

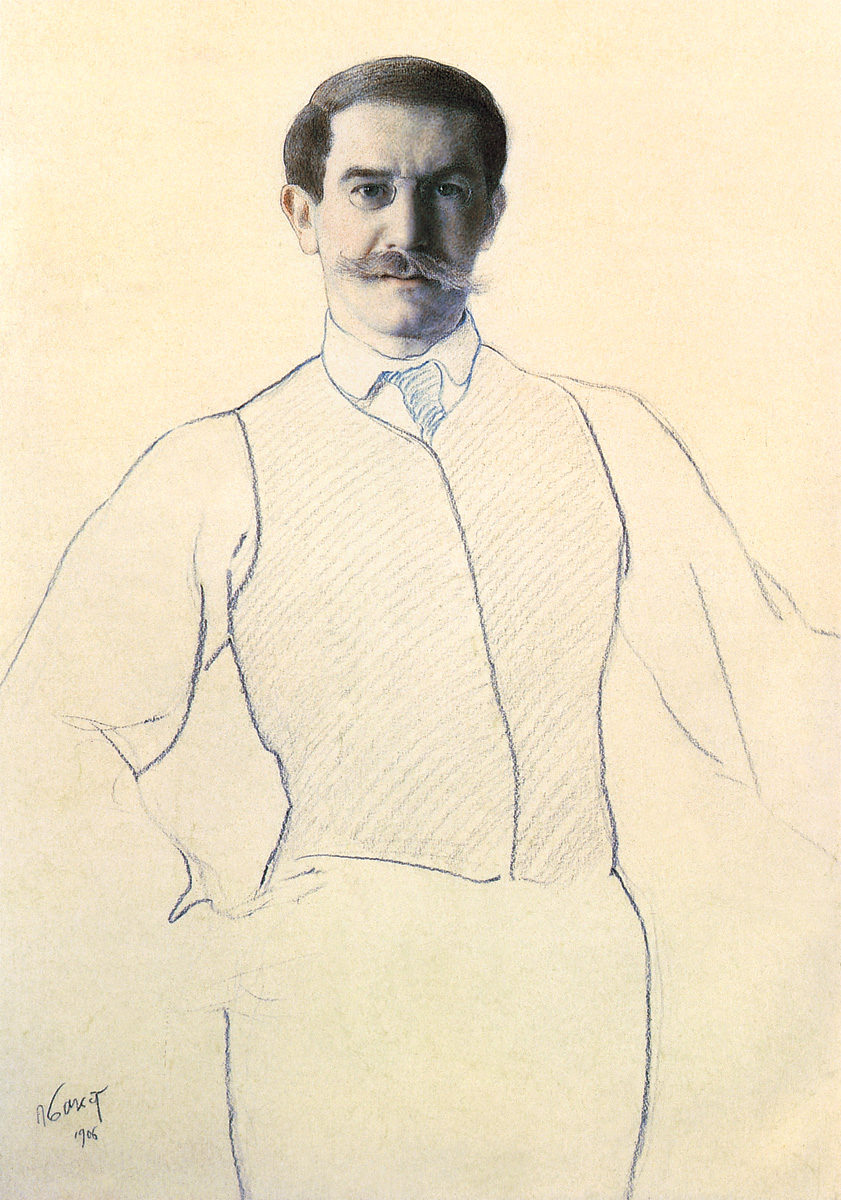

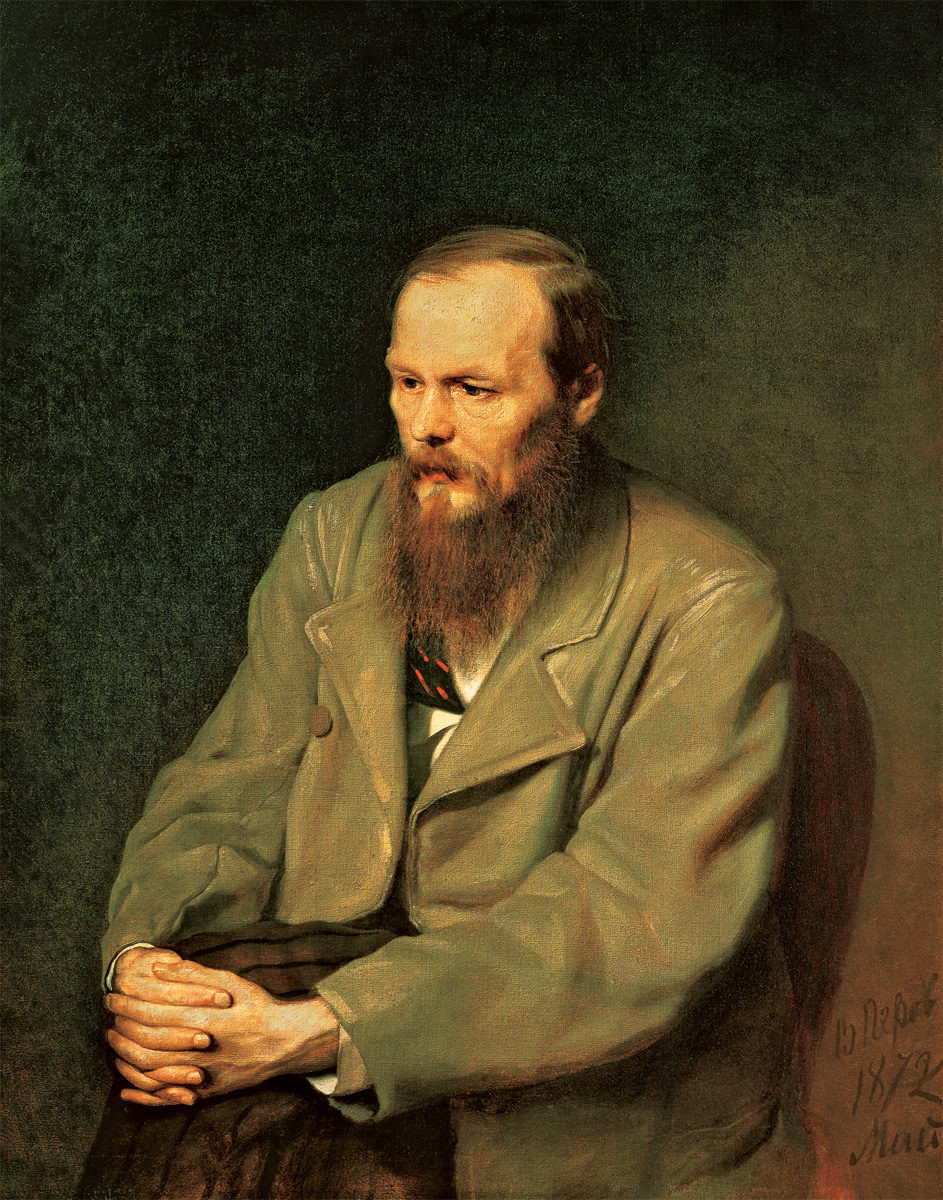

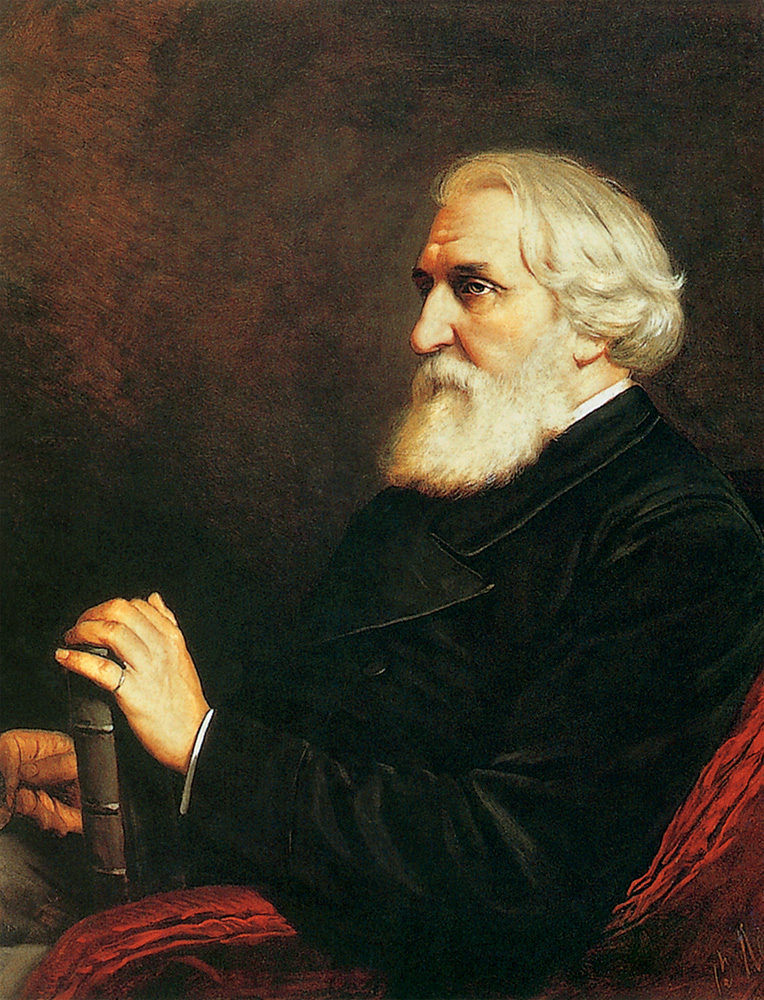

The whole way of life in Russia was undergoing a tremendous series of changes between the 1870s and 1917. A vast range of disparate factors contributed to the restlessness of the period, not only in cultural developments but in the political arena too. The literature of the day both stimulated and reflected these currents of change. Dostoyevsky [4] and Turgenev [5] had much to say on the subject of social injustice. Gorky embraced the growing revolutionary fervour of the turn of the century, and a prose poem written by him in 1901 provided a rallying-call for the reforming movement. The efforts of the peasants to gain more freedom, more rights for themselves and their families, more representation in the government of the day, and the corresponding rigidity of those in power who, fearful of the consequences, sought to suppress these inclinations to natural justice - all this was to result in cataclysmic political upheavals in 1905 and, most dramatically and irrevocably, in 1917. Change was in the air and could not be stifled, in a political any more than in a cultural context.

4. Vasily Perov, Portrait of the writer Feodor Dostoyevsky, 1872. Oil on canvas, 99 x 80.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

5. Vasily Perov, Portrait of the writer Ivan Turgenev, 1872. Oil on canvas, 102 x 80 cm. Russian Museum, St Petersburg

By the 1890s the chief artistic movement of the day in Russia, whose proponents were known as the Itinerants because they showed their work in travelling exhibitions all over the country, had reached the apex of its maturity [6, 7, 8]. Although still full of splendours, the movement was, like a ripe fruit, poised on the verge of decay. Academic painting was the style looked upon with most favour by the official establishment, but this of course was the kiss of death for any impulse towards artistic innovation, stifling fresh thought - not for the first time nor the last in artistic history. So whereas the Itinerants had achieved great progress in endeavouring to break away from the dead hand of official academicism and produce splendid works - historical and genre subjects that still capture the imagination today, as well as magnificent portraits - they were losing their cutting edge and becoming predictable: their standards were beginning to slip.

7. Ivan Shishkine, In the middle of the Plains, 1883. Oil on canvas, 136.5 x 203.5 cm. Russian Art Museum, Kiev.

8. Isaac Levitan, First version of the painting ‘Lake’, 1898-1899. Oil on canvas, 26 x 34 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

With a kind of historical inevitability, the new blood of the World of Art was coming in to take up the mantle of artistic leadership. While it did not put forward anything in the way of fresh theories, it elevated individualism and artistic personality above all other considerations. It has to be remembered that much of this new talent was generously nurtured by the Itinerant masters, whose role in its subsequent development was always acknowledged with gratitude by the younger generation.

Ballet, which had developed in St Petersburg from 1738 as a consequence of Peter the Great's admiration for French and Italian culture and later took root in Moscow as well, remained one of the most popular artistic entertainments throughout the 19th century, achieving new heights of grandeur through the input of such choreographers as Marius Petipa (1822-1910) and composers such as Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) - a partnership responsible for the three evergreen classics Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty [ill. 11] and The Nutcracker [ill. 12]. Opera too was beginning to emerge from the obscurity in which it had languished earlier in the century. Through the encouragement of such enlightened patrons as Savva Mamontov, the works of Tchaikovsky (once again), Balakirev, Borodin, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov were performed to considerable acclaim, and the great bass Chaliapin came to international notice. The fruits of this period are still rapturously hailed today by audiences everywhere.

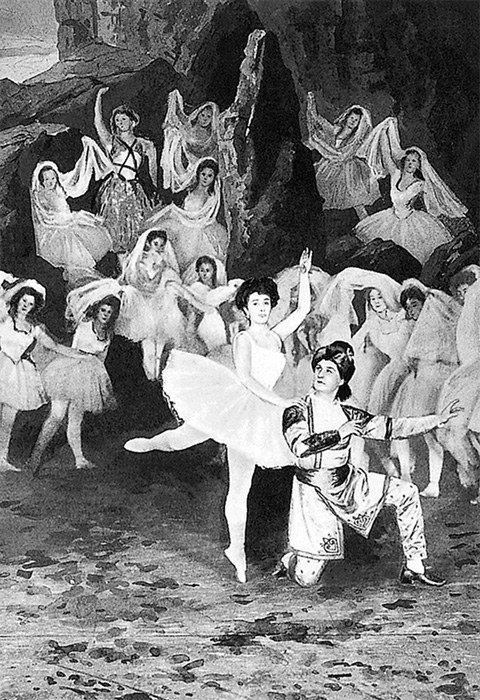

10. Picture of the dancers at Mariinsky theatre Petipa’s team performs the poignant scene ‘The shades’

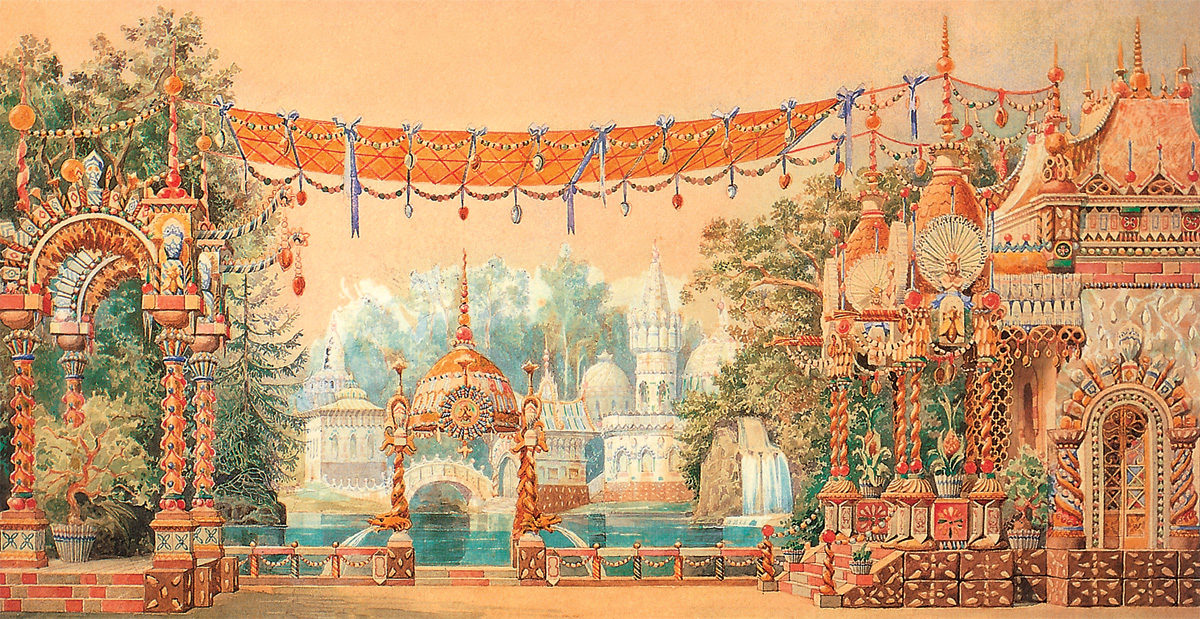

11. The Sleeping Beauty mural on the theme of wakening. Oil on canvas, 210 x 82 cm. Private collection

Yet a good deal of this artistic creativity - wonderful though it was and is, with an appeal to the broadest range of audiences - had about it the stamp of the traditional, even to some extent the safely acceptable. Nothing really innovative sprang out at the audience; little, except perhaps Tchaikovsky's operatic essay in the supernatural, The Queen of Spades, administered a shock to their sensibilities.

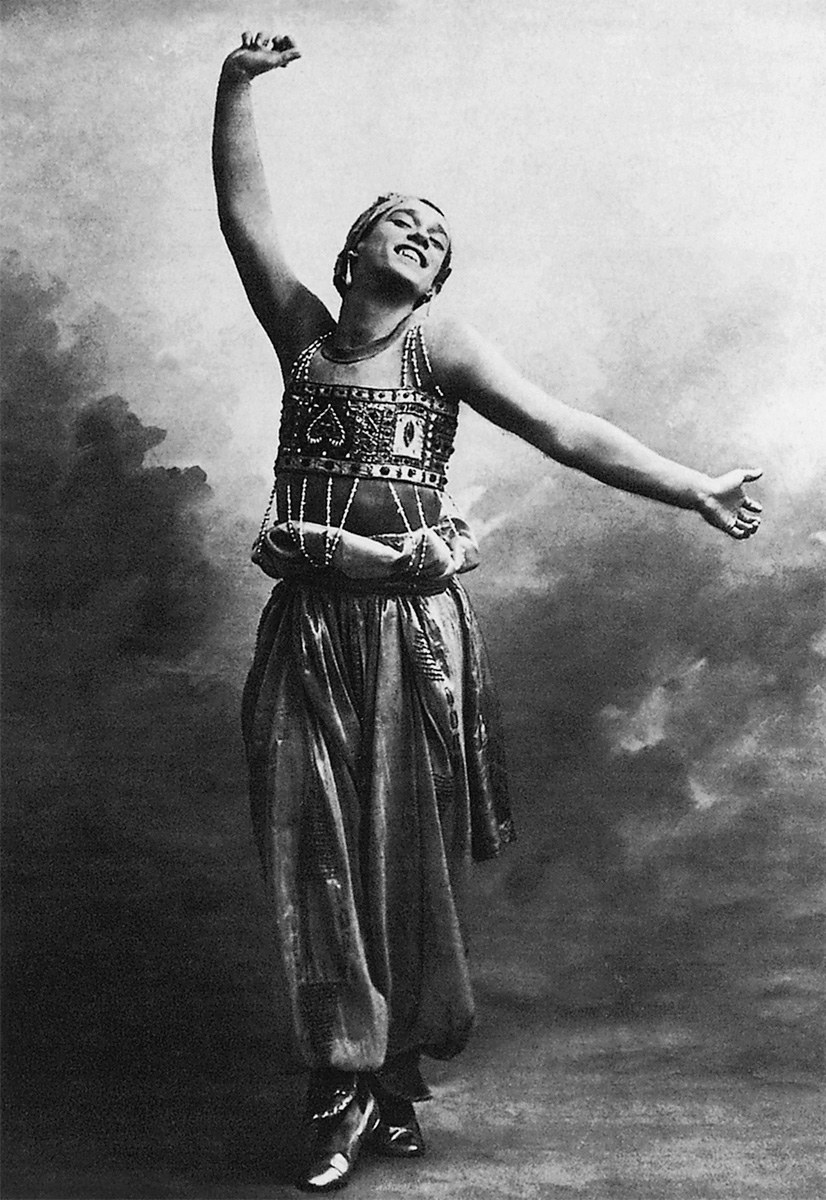

Diaghilev was to change all this. Although he was a man of huge artistic gifts, an able musician with a well-developed critical eye for a painting, it was as a catalyst for the gifts of others that he achieved the position of eminence from which his name rings down through the decades. Somehow he had the vision to put together an infinite variety of widely divergent talents and see what happened. Taking a cue from Mamontov, who encouraged the production of interesting new operas in collaboration with leading artists, but going far beyond that generous patron, Diaghilev and his fellow-founders of Mir Iskusstva (the World of Art) drew into their orbit artists, musicians, dancers and singers whose names are today a byword for excitement, for colour and glamour, and for the shock value of a radical new approach to the arts. Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, the immediate offshoot of this artistic grouping, was to be the showcase for the genius of the painters Benois and Picasso as well as Bakst; the composers Ravel, de Falla, Debussy and Stravinsky; the choreographer Fokine and the dancers Pavlova, Karsavina and Nijinsky [ill. 13]. Bakst fits effortlessly into this matchless roll-call of stars.