NATURE, AND THE SETTLEMENT OF SIBERIA

SIBERIA: THE GEOGRAPHICAL FACTS

Understood for close on three centuries now to be no more than a geographical extension of the Russian state, Siberia stretches from the icy Arctic Ocean in the north to borders with Kazakhstan, with Mongolia and with China in the south, from the great chain of the Ural Mountains in the west all the way over to the Pacific Ocean in the east. Within that span it covers no fewer than eight different time zones and around 20° latitude (between 50° and 70° North) – and thus actually represents more than two-thirds of the entire territory of Russia: some 4.9 million miles² (12.7 million km²).

Many Europeans think of Siberia as one huge wilderness remote and hostile to human habitation, mostly iced over, darkened by the polar night for a good proportion of the year. And yet Siberia is nothing if not diverse. From north to south there are a number of large areas that are completely different from each other in climate and terrain and thus in the local flora and fauna. The Arctic wastes shade into the tundra with its permafrost; further south, the tundra in turn shades into the slightly warmer zones where scrubby trees will grow; further south still is the evergreen coniferous forest of the taiga; continuing south, there are the fertile steppes and then the arid steppes – and all these various ecological areas come with their own topographical relief, from low-level flatlands to massively towering peaks.

Occupying the greater part of this vast landmass, the central Siberian plateau is bounded to the north, east and south by an enormous amphitheatre of mountain chains. To the north and east are the mountains of Verkhoyansk, which at their highest reach 9,097 feet (2,389 metres). Forming Siberia’s southern boundary are the Sayan mountains (9,612 feet/2,930 metres) and the ranges of the Altai (which at Mt Belukha top out at 14,783 feet/4,506 metres). Within these various chains lie the sources of the three great Siberian rivers, the Ob, the Yenisey (a name derived from Evenki ioanessi ‘great river’), and the Lena. These rivers are frozen over for much of the year – between October/November and May/June – but at other times flow powerfully across Siberia for about 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometres) until they reach the cold Arctic Ocean.

The Arctic Ocean to the north of Siberia is itself divided into several regional seas –from west to east, the Kara Sea, the Laptev Sea and the East Siberian Sea – which are likewise choked with a thick blanket of ice for at least ten months of the year. The summer period of remission is brief: just the remaining two months, July and August.

In these northerly latitudes, the ground surface – permanently frozen – is mostly shingle, perhaps covered in algae, lichens and mosses. This is the true Arctic wilderness and characterizes most of the islands, especially those off the coast of the Taimyr Peninsula. Seals, walruses, belugas and polar bears populate the coastline.

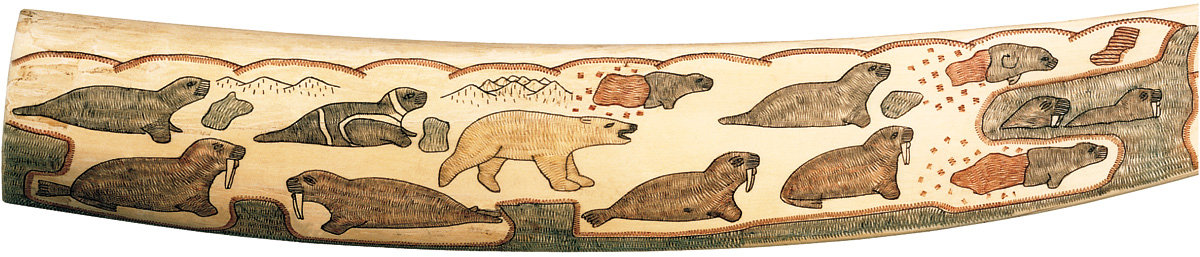

4. Carved walrus tusk, in colour. Fragment, 1930s, Chukchi, Chukotskiy Peninsula. Walrus tusk ivory, 57 x 6 cm.

As distance increases from the north pole southwards, the Arctic wilderness turns into the tundra – a bare region in which only lichens, mosses and short, scrubby trees (dwarf species of birch or willow, mainly) shroud the ground, with some spiky plants and Arctic grasses. Winter in the tundra is lengthy – between eight and ten months – and cold. At the end of November the sun dips below the horizon and does not return. This is the polar night, which in the tundra lasts for two or three months (compared with up to six months in the Arctic wilderness). Then finally, in January, the sun reappears once more, and the days little by little lengthen even as the nights little by little become shorter. This goes on until, from sometime in May to sometime in July, the sun doesn’t leave the sky at all.

Summer in the Arctic is not so much warm as brisk – temperatures average from 5-12°C (40-68°F) – and short. Towards mid-August, heralding the end of summertime, the tundra takes on its autumnal coloration. Leaves on the woody plants turn golden, the lichens and mosses turn grey, while the wild mushrooms sprout in abundance and the berries ripen in a vast moving red and orange carpet.

The tundra is the home of the reindeer (caribou), of the Arctic wolf, the wolverine (glutton), the Arctic fox, the lemming, the great white owl, and the ptarmigan (the gallinaceous bird that, unlike any other, winters by hiding itself under the snow).

In spring, the tundra welcomes the arrival of the many migratory birds – geese, swans, ducks, terns, gulls and others – that come to breed.

The terrain tends to be marshy, with a scattering of thousands of little lakes of no real depth. Baron Eddel, a traveller who a hundred years or so ago explored the lower reaches of the Indigirka and the Kolyma Rivers, recalled in his memoirs that ‘to draw a map of all these lakes, all you need to do is dip a paintbrush in blue watercolour and bespeckle the paper all over with it’. The tundra is swampy because of the presence beneath the topsoil of permafrost – a stratum of soil frozen solid over thousands of years sometimes to a depth of 1,000 feet (300 metres) or more, whereas the topsoil itself may be no more than a foot (30centimetres) deep. The permafrost is impervious, which means that although annual rainfall may be comparatively low, the water cannot drain away or be absorbed. Nor does it evaporate, because the air is already extremely humid and the heat is not sufficient.

The southern boundary of the permafrost – a line that actually runs through a little less than two-thirds of the area covered by the Russian state – lies north of the valleys of the lower Tunguska (a tributary of the Yenisey) and the Vilyuy (a tributary of the Lena).

It is in the north-east of Siberia that the permafrost is most extensive. To the north of Yakutia the subsoil keeps turning up the fossilized remains of animals – whole cemeteries of mammoths trapped in thick layers of frozen sediments, their bones and their ivory tusks forming colossal repositories.

It is also in Yakutia that the coldest place in the Northern hemisphere is located – at Oymyakon, in the Verkhoyansk mountains. Here, the average temperature in January is somewhere between -48°C and –50°C (-54°F and -58°F), occasionally getting down to as low as -70°C (-94°F). However, the air is so dry, and there is no wind at all, so these temperatures do not feel as extreme as they might.

Further south, a change in vegetation indicates a difference in the prevailing climate and conditions. The number of dwarf trees and bushes increases greatly. This is an intermediate zone between tundra and taiga (which many people think of as an individual zone in its own right). Continuing south, the vegetation diversifies. The trees become more numerous and grow much taller. Finally, the environment is that of the taiga – the huge northern forest that cloaks the greater part of Russia.

Comprising mostly conifers (larch, pine and Siberian cedar) but also in the north birch, willow and aspen, in the south and west deciduous species, the taiga forests are home to an important group of larger predatory animals (bears, wolverines, wolves and lynxes), foraging omnivores (foxes, sables, polecats, weasels, ermines, mink and martens), ungulates (deer and elk) and birds (capercaillies, partridges, woodpeckers and nutcrackers). Winters in this region are very long and very cold. Summers, however, can be warm in the central part of the region where the annual range of temperatures can be as wide as 100 degrees on the Celsius scale (180 degrees on the Fahrenheit scale) – propitious times for the insects, especially for the mosquitoes, midges and flies for which the tundra, with its multitudinous marshes and lakes, has been the ideal breeding-ground.

12. Yukaghir man’s costume. Yakutia, Kolyma Oblast. Incorporating the skins and furs of reindeer, seal, dog, wolverine and squirrel; linen and cotton cloth; reindeer hair; and glass beads. Coat length: 100 cm; circumference at the chest: 86 cm; at the trouser-legs: 22 cm.

14. Box for containing vessels. Evenki, Sakhalin island, 1962. Wood, cured hide (leather), reindeer fur, sable fur, bearskin, cloth, matt canvas, 17 x 33 cm.

Further south still, the taiga gives way first to the fertile steppes and then to the arid steppes – areas typical of northern Central Asia and Mongolia. Here, the climate is by no means unpleasant: summers are fairly long and warm, and the rainfall is light although the prevailing winds tend to be strong. Much of the steppes is covered by vast prairies of tall grasses growing on humus-rich fertile soil.

It is an area well suited to farming, both of crops and of livestock. But there is plenty of wildlife too: marmots, voles and fieldmice, hamsters, jerboas, hares, foxes, saiga antelopes and badgers. Birds of the steppes include bustards, kestrels, Asiatic white cranes and many more.

Amid the arid steppes north of Mongolia, over a length of an extraordinary 400 miles (635 kilometres), stretches the largest inland source of fresh water in the world: Lake Baikal. In places it is 5,300 feet (1,620 metres) deep. A miracle of nature, Lake Baikal provides essential water for all kinds of local populations – including of course the creatures that live in it, which are now regrettably under severe threat from the pollution exuded into the lake as effluent from the timber workings up the rivers that flow into it.

The most easterly part of Russia is an area drained largely by rivers that flow out into the Pacific Ocean – rivers such as the Anadyr in the north and the Amur in the south. In the area around the Amur (which for a time forms the boundary with China), the climate and the overall humidity are favourable to the growth of mixed forest, particularly of broadleaved trees like limes, aspens or oaks. The wildlife here is much the same as in the taiga, with the addition of the Asiatic tiger, the leopard, the civet, the genet, the goral (a goat-like antelope related to the chamois), the sika deer and a great number of bird species.

Siberia is rich in natural resources. It has minerals that can be extracted – gold, silver, tin, diamonds, nickel and phosphates; it has abundant means for supplying energy – huge reserves of oil and petroleum and of natural gas, extensive coal seams, and a great number of fast-flowing waterways; and it has a wealth of other useful and commercial materials – the timber in its forests and the pelts of its animals. In many ways, then, it is Russia’s warehouse of goodies, contributing around one-fifth of the state’s overall gross national product.

And yet this is the territory used by the Tsars as a penal colony, a vast concentration camp for ‘internal exiles’. This too is where, simply because it contained all those goodies, massive migrations of people were organized and resettled during the whole of the period of Soviet domination, despite the generally inhospitable nature of much of the territory to human occupation. Close on 32 million souls were sent to take part in exploiting Siberia’s resources, and many of them (and their descendants) are still there, in the thousands of towns, industrial centres and mining camps set up specifically – places like Vorkuta, Noril’sk, Novosibirsk, Krasnoyarsk, Bratsk, Irkutsk, Kemerovo, Prokop’yevsk, Angarsk, Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Yakutsk, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, Magadan, Khabarovsk, Vladivostok and Ussuriysk.

25. ‘Flying object’ and pen. Eskimo (Uit), Chukchi Peninsula, 3rd-4th century AD. Walrus ivory, length: I) 6.2 cm, II) 13.7 cm.

THE FIRST HUMAN COLONIZERS

Penal colony, place of banishment, ‘northern Eldorado’ for millions of Soviet migrants – Siberia today is populated by members of considerably more than a hundred different ethnic groups from all over what used to be the Soviet Union. It is not altogether surprising, then, that this vast northerly and easterly area is far less well known for being the cradle of cultures some of which are many thousands of years old. Representatives of around thirty of these aboriginal groups still live in the region, although some of the groups now comprise very few individuals (and are accordingly lumped together by some anthropologists under misleadingly blanket-style descriptive names, like ‘the northerly folk’).

The fact is that from the far north down to the southern steppes and across to the most easterly region, Siberia displays a rich panorama of local cultures, traditions, languages and different ways of life. The history of these aboriginal groups, however, has in general been as misunderstood, or as unconscionably misinterpreted, as has in times not so long past the history of such other aboriginal peoples as the Native American Indians or the Australian Aborigines. Now, at the dawning of the 21st century, this heritage of human endeavour through the millennia is fast eroding away and may soon be lost for ever.

The earliest incomers

Archaeologists have turned up evidence of the presence of human residents in this part of the world as early as in the Upper Palaeolithic age between 20,000 and 25,000 years ago. Scattered remains throughout Siberia and along the northerly coastline indicate that by Neolithic times much of northern Asia was inhabited by people with some pretensions to culture, for they certainly seem, all those thousands of years ago, to have differentiated between the material and the spiritual sides of life, and to have appreciated their own forms of art.

The steppes of southern Siberia and the area around Lake Baikal were first settled by tribes who were livestock-herders and crop-growers. In the neighbouring regions of the taiga, people lived instead by hunting and fishing. It is probable that the communities in what is now Yakutia and the residents of the Baikal area maintained fairly close connections, which would account for the well-established cultural group that occupied the area between the Angara and Lena rivers. Archaeological evidence relating to this group is fairly plentiful, and includes rock carvings that appear to reveal particular aspects of their spiritual beliefs (involving rites of passage, Neolithic hunting rituals, and so forth).

The regions of the tundra to the north-east of Siberia were occupied by nomadic tribes who lived by hunting reindeer (rather than herding them) and by fishing. Sites discovered between the rivers Olenëk and Kolyma have proved that the ancestors of today’s Yukaghirs lived by hunting and fishing, in total isolation, from the Neolithic period for at least another thousand years.

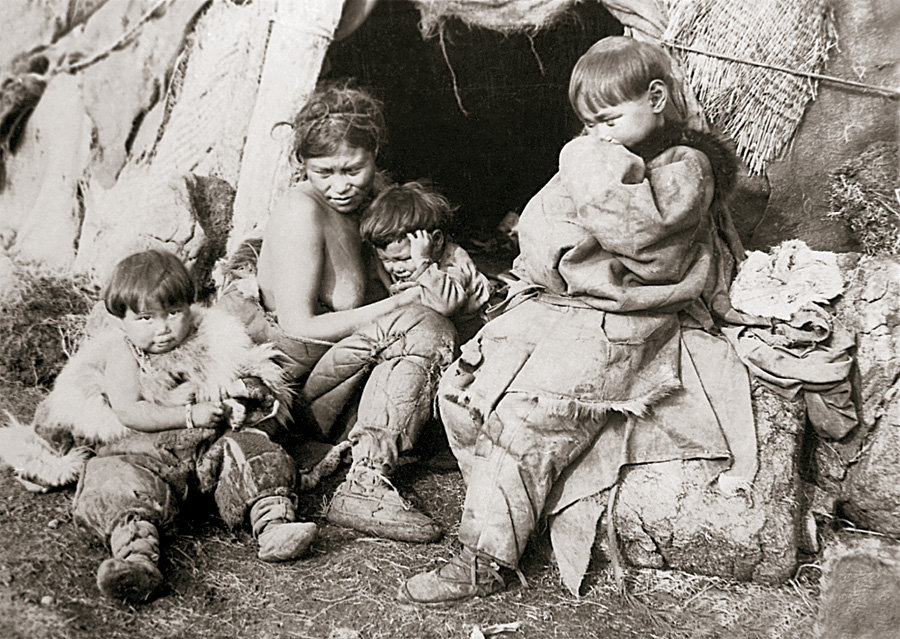

Elsewhere in the north-east were regions occupied by ancestors of the present-day Chukchis and Eskimos, who were able to live a settled, residential life because they depended on the resources of the sea. In time, the way of life of these marine predators became widespread, from the shores of the Bering Sea over the length of the Arctic coastline.

Inland, many communities at first lived a nomadic form of existence based upon hunting wild reindeer. The ‘domestication’ of the reindeer – or at least the discovery of the way of life that involved herding the semi-domesticated creature – was a highly progressive stage in the overall history of humans’ successfully taking up residence in the tundra and the taiga.

The great age of human migration in Central Asia fell between the 10th and 13th centuries AD. This was the time when an influx of new people into Siberia from the south pushed the original inhabitants there northwards and eastwards. Palaeo-Asiatic groups such as the Chukchis and Koryaks, and Tungusic tribespeople such as the Evenki and the Eveni, formerly resident in what today is Yakutia, thus found themselves hounded from their homelands and forced towards the northern and eastern margins by the ancestors of modern Yakuts – who had themselves been pushed northwards by Mongol-speaking invaders.

27. Yakut toys: I) reindeer, II) seal. I) Yakutia, II) Turukhansk region; I) 1908, II) 1903. Wood, length: I) 22 cm, II) 18 cm; height: I) 4 cm, II) 13 cm.

28. Protection for the hands when using a bow and arrow. Chukchi, Uit, Chukchi Peninsula, I) 2nd to 4th century AD, II) 1904-1907. Walrus ivory, skin, length: I) 11.3 cm, II) 13 cm.

29. Schematic representations of the human form. Eskimo (Uit), Chukchi Peninsula, 3rd-4th century AD. Walrus ivory, height: I) 4.7 cm, II) 3.7 cm, III) 3.8 cm.

31. Sculpture in miniature: representations of aquatic birds, with a clasp in the form of a bear. Eskimo (Uit), Chukchi Peninsula, 3rd-4th century AD. Walrus ivory. Diameter of the bird figurines: I) 3.2 cm, II) 2.8 cm; height: I) 3.2 cm, II) 3.5 cm; length of the clasp: 5.7 cm.

Until the 16th and 17th centuries, the peoples of Siberia had no contact at all with any European civilization. All were isolated, each community generally maintaining some form of relations only with neighbouring communities, and then often only if those communities were from the same cultural background. The names these people of the north give themselves in their own languages frequently bear witness to this aspect of primal isolation: most of the tribal names mean simply ‘the people’. In this way, the Chukchis call themselves the Lyg’oravetlat, and the Eskimos think of themselves as the Uit, Yuit or Yupik, all of which mean ‘the (real) people’.

Likewise, the Nenets know themselves as Khasava ‘people’, whereas the Olchi people, the Oroki and the Orochon people reckon that they are all Nani which, like Nanai – for several decades now the official name of their neighbouring tribal group, otherwise known as the Gold people – would seem to mean ‘the people of the soil’ (just as in English human may be related to humus).

When the Russians took over Siberia and its inhabitants, they tended to rechristen the groups they came across, often borrowing the neighbouring people’s name for each community rather than the indigenous name. This is, for example, how the peoples now known as Yakuts and Yukaghirs got their current names. As far as they are concerned, they are the Sakha and the Odul respectively – but in Evenki they were the Yakut ‘the yak (or cow) people’ and the Yukaghirs ‘the ice dwellers’ – and that is the way they are now known all over the world. Similarly, the peoples known by much of the world (but not in countries where there are Lapps) as Khanty and Mansis recognize themselves only as Ostyaks or Vogul people. The Eveni think of themselves as the Lamut.

Diverse environments and ways of life

From west to east inside the zone of the tundra that borders the coast of the Arctic Ocean, nomadic groups who live by herding reindeer, by hunting and by fishing, successively neighbour and occasionally overlap with each other. In that part which is in Russian Europe, on the Kola Peninsula, live the Saami (or Sami), better known as the Lapps, who also live in the north of Finland, Norway and Sweden. From the banks of the Dvina to the Yenisey, and particularly on the Yamal Peninsula, live the Nenets, whose territory thus just reaches into the Taimyr Peninsula – the area which, since prehistoric times, has been the home of the Nganassani, the most northerly-based people in the whole of Russian Asia. The area from the River Taz to the River Turukhan (a tributary of the Yenisey) is the home of the Selkup. Now almost disappeared, the Enets – culturally closely related to both the Nenets and the Nganassani – live along the banks of the Yenisey, where they come into contact with the Dolgans, a relatively new ethnic group which have not been around for much more than a couple of centuries, and which derive from combined Yakut, Evenki and Russian antecedents. The Dolgans are also prevalent in the north-east of Yakutia. Displaced ever northwards by the Yakuts infiltrating from the south, groups of Evenki established themselves on the lower courses of the Lena, which forms the western boundary of an enormous territory dominated for at least one millennium, as far as the River Kolyma, by the Yukaghirs. Of the Yukaghirs there are now only a few hundred left, generally in the Kolyma Basin not far from the mouth of the Alazeya, although some live further south in the taiga on the banks of the River Yasachnaya (Upper Kolyma). The Eveni people, also displaced by incoming Yakuts, once lived in what are now the lands of the Yukaghirs in northern Yakutia, and as late as the 19th century found themselves pushed all the way to the extreme north-east to live among the Chukchis and their neighbours to the south, in Kamchatka, the reindeer-herding Koryaks.

Some of these ethnic groups of the tundra are also represented in the more southerly zones of the taiga, including, for instance, the Nenets, the Eveni and the Evenki. The Evenki, in fact, are scattered across a vast area bounded in the west by a line between the Rivers Ob and Irtysh, in the east by the coastline of the Sea of Okhotsk, and in the south by the Upper Tunguska (a tributary of the Yenisey), the Angara, Lake Baikal, and by the Amur River. The taiga affords a fairly good living for the nomadic peoples who hunt and fish, or who hunt when they are not herding reindeer. In the west, on the plain of the Ob, is the land of the Khanty and the Mansis – closely related culturally and linguistically – who have a variety of lifestyles, based on hunting, fishing, herding reindeer and breeding other livestock. The non-nomadic (residential) Kets hunt and fish on the edges of the Yenisey. Pouring up from the south during the 14th century, the Yakuts established themselves firmly on the middle courses of the Lena. This horse and cattle-breeding people finally occupied an area as large as the Indian subcontinent, bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, pushing before them to the north and east those groups that had been there first – the Evenki, the Eveni, the Yukaghirs and the Chukchis. In the south of Siberia, towards the frontier with Mongolia between the Ob and the Yenisey, the Altai people (or Oirot), the Tuva people (or Tuvinians or Soyot), a little further northwards the Khakass people and, to the east of Lake Baikal, the Buryats are all specialists in raising horned animals Mongolian-style. Yet the Karagas people (or Tofalars) – a very small ethnic group to the west of Lake Baikal – herd reindeer and live by hunting and fishing in the taiga.

The peoples of the Pacific coastline, from the Bering Strait in the north down to the Chinese border, mostly hold to a traditionally non-nomadic (residential) lifestyle that involves hunting marine mammals. These include the Aleuts of the Commander (Komandorski) Islands, separated from their ethnic brethren on the other islands to the east, the Aleutian Islands, not only by the Russian-American border but also by the international date-line. In this way they are very like the Uit (Yuit or Eskimos) who live on the shores of the Bering Strait, cut off from their ethnic cousins in Alaska and Canada. Inhabitants here additionally include communities of Chukchis and Koryaks, smaller groups of semi-nomadic Eveni people living on the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk (in the Magadan region), and, on the island of Sakhalin, the Nivkhi (or Gilyaks).

Finally, still in the extreme east of Siberia, but further south around the border with China, is where the Eveni and the Evenki live, in close touch with the Olchi, the Orochon people, the Oroki, the Negidal people and the Udekhe, all originally inhabitants of the Amur Basin. Before the Russians took over, these semi-nomadic groups who depend on hunting and fishing were for centuries, if not millennia, under the thumb of their equally dominant neighbours, the Chinese.

38. Quiver and arrows. Chukchi, the Anadyr area, 1904-1907. Dried sealskin, stitched with reindeer-hide; wood, metal, bone, feathers. Quiver length: 88 cm, width: 21.5 cm; length of arrows: 76.5 cm, 79 cm, 77.3 cm, 76.5 cm.

Linguistic links

Although the peoples of Siberia may no longer live in what used to be their ancestral territories and are scattered in groups here and there in no particular pattern, they may nonetheless be regarded as stemming ultimately from only eight independent ‘nations’, based not on racial characteristics but on language families. Most, in fact, belong to one or other of just two – the Uralic and the Altaic language super-families.

In the west of Siberia, the Uralic super-family is represented by the Khanty and the Mansis who are related to the Finno-Ugric branch (which includes Lapps and Finns), and by their northern neighbours the Nenets, the Enets, the Nganassani and the Selkup who make up the Samoyedic branch. The Evenki, the Eveni and the peoples of the Amur region all belong to the Tungusic family, a branch of the Altaic super-family, which also includes in its Turkic branch the Yakuts, the Khakass people, the Tuva people, the Altai people, the Dolgans, the Shorians and the Karagas people, and in its Mongolian branch the Buryats. The Kets around the Yenisey and the Nivkhi on Sakhalin each speak a language that appears not to be related to any other. Independent of the Uralic and Altaic super-family communities listed above, the peoples of north-eastern Siberia form three different linguistic groups: Chukchi-Koryak-Kamchadal (occasionally referred to as ‘palaeo-Asiatic’) which includes the tongues of the Chukchis, the Koryaks, the Kereks and the Itelmen (the latter of whom speak Kamchadal); the Eskimo-Aleut group which combines the Uit and the Aleuts; and finally the Yukaghir-Chuvantsi group which self-evidently comprises the languages of the Yukaghirs and the Chuvantsi, although these two may be said to be grouped together only by convention.

The majority of the ethnic groups in Siberia have a couple of major factors in common: an area of dispersal so wide as to be significant for the continuing survival of each group, and the varying influences of unrelated neighbouring groups on the larger groups that do live as ethnic communities. So, for example, the Koryaks – like the Chukchis or the Eveni people – may themselves be divided into two groups: one that lives on the coast by hunting marine mammals and by fishing, the other that lives as nomads who herd reindeer and follow them inland in due season. Such groups, although originally speaking precisely the same language tend after all this time to speak different dialects of the parent language. And in the case of the Yukaghirs, the dialects have become so different and so mutually unintelligible that some linguistic anthropologists prefer to regard the Yukaghirs of the taiga who live by hunting and fishing as a completely different ethnic group from the Yukaghirs of the tundra who live by herding reindeer.

But no matter how different the languages and the corresponding dialects have become, no matter what other linguistic barriers there are between the residents of Siberia, it remains a salient fact that today it is (and has for a time been) the Russian language that has in many areas displaced the ancestral languages for ordinary daily purposes. The result of compulsory assimilation programmes and the deliberate blurring of ethnic differences, it may well be that even now the numbers of speakers of some of these tongues are so few as not to be able to prevent them from dying out altogether.

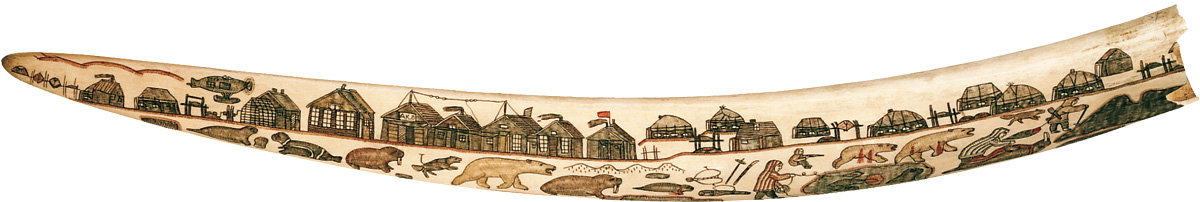

40. Carved walrus tusk in colour (primary face). Chukchi, Chukchi Peninsula, 1930s. Walrus ivory, length: 62 cm, width: 6 cm.

42. Carved walrus tusk in colour (secondary face). Fragment, Chukchi, Chukchi Peninsula, 1930s. Length: 62 cm, width: 6 cm.

44. Balls for playing games, I) with the feet, II) with the hands. Chukchi, Eskimo (Uit), Chukchi Peninsula, I) 1974, II) 1904-1907. Sealskin and seal hair, stitched with reindeer-hide. Diameter: I) 58 cm, II) 25 cm.

Cultures on the edge of extinction

With a total of some 32 million inhabitants, Siberia can nonetheless boast no more than a million and a half of the aboriginal populations. Indeed, apart from the Buryats, the Yakuts, the Tuva people, the Khakass people, the Shorians and the Altai people, no fewer than 26 other ethnic groups are officially (according to figures taken from the Soviet census in 1989) recorded as ‘ultra-minorities’, comprising between them no more than around 180,000 individuals, and thus as groups ‘doomed to certain extinction’.

The most numerous ethnic group of these is that of the Nenets who, in the same census, were counted at 34,190 persons. Now the Nenets are one of the peoples of Siberia who have best preserved their traditional way of life and culture. The Evenki, almost as numerous (29,901 persons), have on the other hand been subject to considerable assimilation, especially into Yakut groups. Next in order of numerical importance are the Khanty (22,283 persons), then the Eveni (17,055), the Shorians (16,652), the Chukchis (15,107), the Nanai people (11,833), the Koryaks (8,942), the Mansis (8,279), the Dolgans (6,584) and the Nivkhi (4,631). The remaining ethnic groups are undoubtedly ‘ultra-minorities’:

• The Selkup, the Olchi, the Itelmen and the Udekhe make up between 2,000 and 4,000 people

• The Chuvantsi, the Nganassi, the Yukaghirs, the Kets, the Saami of west-ern Siberia and the Uit of eastern Siberia number between 1,000 and 2,000 people

• Some ethnic groups comprise no more than a few hundred men and women: these are the Orochon people (883 persons), the Karagas people (722), the Aleuts of eastern Siberia (644), the Negidal people (587), the Enets (198) and the Oroki (179)

• One really tiny ethnic group – so small that it was not even counted sep-arately in the census – was that of the Kereks of southern Chukotka, who in total numbered fewer than 50 representatives.

Assimilation of language and of culture has affected all of these small ethnic groups to one extent or another, but so has such assimilation also affected – if less seriously – the more numerously significant groups, such as the Buryats (listed in the census as numbering 417,425 persons), the Yakuts (380,242), the Tuva people (206,160), the Khakass people (78,500) and the Altai people (69,409). Today, just one small proportion of Siberia’s original inhabitants preserves an ancient and traditional way of life, continues on a daily basis to practise and to teach its ancestral rituals and language. But such efforts are puny in the face of what is massed against them, notably the effects of ‘modern life’ and ‘technological development’ (which include an increased mortality rate, severely depressed morale, stress disorders and diseases, alcoholism, high unemployment, soaring suicides and other measures of progress). It was the frenetic pace at which assimilation was overtaking all these various ethnic groups that caused them to feature in The Red Book of Ethnic Groups on the Verge of Disappearing, published during the last years of the Soviet Union.

To understand how this demographic and cultural erosion came about, it is necessary to turn back and look once more at history …

COLLISION OF WORLDS

The conquest of Siberia

For a long time blocked by the unwelcome presence of the Tatars, the extension of the Russian Empire on the far side of the Ural Mountains was made possible only on the eventual defeat of the Tatar khan, Kuchum, at the hands of Yermak and his Cossack forces in 1582. The conquest of Siberia was then accomplished at remarkable speed, albeit at the expense of a great deal of blood.

As they continued in their warlike progress ever eastwards, the Cossacks demanded tribute from the populations they overran – tribute not in the form of money but of furs: the yassak. They also constructed forts to control these new subjects of the Russian Tsar … and in which to stockpile the precious tribute. Some of the tribespeople, such as the Yakuts, surrendered without much resistance (the Russians were excellent at knowing whom to treat gently and offer gifts to), only to rise in revolt soon afterwards. It was more common, however, for the tribal groups – like the Khanty and the Mansis, the Khakass people, the Evenki and the Eveni people – to act with the utmost ferocity in staving off for as long as possible this hated colonization. The pacification of the north-east of Siberia, from the end of the 17th century, thus took place amid horrifically bloody scenes of combat. The Yukaghirs, and then the Itelmen, sustained heavy losses; whole communities of them were wiped out. The Koryaks kept up their defiant opposition for nigh on 25 years. And only after a full 60 years were the pertinacious Chukchis – a warrior nation – finally subdued, and even then only at the wrong end of the cannons brought in specially by the Russians, forced to adopt unusual methods.

48. For the hands of a warrior. Chukchi, the Anadyr area, 1904-1907. Reindeer antler, sealskin, length: I) 36.5 cm, II) 37 cm.

The Tsarist period: colonization and ethnic decline

The incorporation of Siberia into the Russian Empire was accompanied by an influx of colonists and the inauguration of a social system designed to exploit the indigenous populations. The consequences were manifold and immediate: the aboriginal peoples were forcibly suppressed, and made thoroughly aware of their insignificant numeric strength.

As happened in the Americas, the colonists who came to Siberia brought with them all kinds of viral and bacterial diseases against which the aboriginal peoples had no immunity – smallpox, measles, syphilis among them. Recurrent epidemics racked the defenceless communities. Smallpox alone accounted for the deaths of several thousand Yukaghirs.

The Russians also brought with them new addictions in the form of desirable commodities such as vodka (something else the locals had no immunity against), tobacco, sugar and even bread, which they used in outrageously unequal bartering for the skins and furs so highly sought-after in Europe.

The yassak system likewise, over time, was to have repercussions that were all but catastrophic for the peoples of Siberia. Together with the diseases it represented a principal reason for the declining numbers in the population of the ethnic groups during the Tsarist period. So oppressive was the levy of furs that local inhabitants were often forced to go to extreme lengths to get hold of ‘the golden pelt’. If the levy had not been fully supplied by the due date, the officers responsible for collecting it had various additional methods of extracting it. One of the more common was to kidnap someone and hold him or her to ransom until it was forthcoming, usually someone important in the community of whoever was defaulting on the tax – perhaps one of the best hunters, a headman, possibly one of the tribal elders. In this way quite often having insufficient time to see to keeping themselves properly fed, exhausted, obliged to do without their leaders or the people most required for the survival of their group, the local people all too frequently underwent periods of famine which, in the environmental conditions natural to the cold north and to Siberia in general, were particularly, insidiously, destructive.

At the beginning of the 18th century, brutality and massacres accompanied the forcible conversion to Christianity of the indigenous peoples. The Russians had realized that ‘gentle’ methods did not seem to be working. Simultaneously, the colonists continued to exploit the people shamelessly. It was nonetheless only a little later, in 1824, that an official Code of Practice was promulgated by the authorities that was meant to protect the peoples of Siberia from abuses of these kinds. Nothing much came of it.

In the space of two centuries, the conquest and the colonization of Siberia caused a general – in some cases, even permanent – decline in the fortunes of the aboriginal populations. By the end of the 19th century some of the ethnic groups were in such a sorry state (by way of depletion in numbers, wretched health, poverty and low morale) that even then their disappearance altogether was regarded as being only a matter of time – and a short time at that.

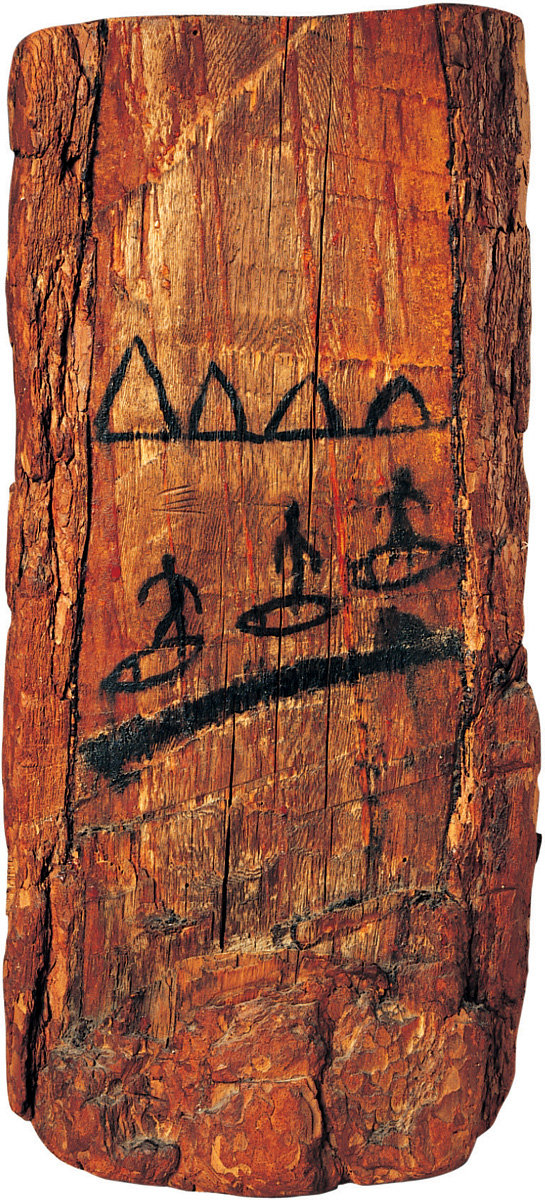

51. Pictographic letter. Evenki, Yenisey Province, 1908. Wood (pine), charcoal, length: 59 cm, width: 26 cm.

The Committee of the North: the hope of renewal

In the early years following the October Revolution, the Soviet authorities took it upon themselves to try to redress the disastrous situation that by then had overtaken most of the peoples of Siberia. A special policy was formulated to protect the ethnic groups that were in the greatest need (of which they listed 26), and, at the initiative of the anthropologist and Chukchi scholar Vladimir Bogoraz (who wrote under the pseudonym N. A. Tan), the Committee of the North was set up to introduce supportive measures. The ‘Peoples of the North’ were duly exempted from all forms of taxation and from conscription into military service. Some social amenities were placed at the disposal of communities throughout Siberia, each major locality receiving a small schoolhouse, a police station, an infirmary, a veterinarian clinic and a weather station as well as, generally, a small Lenin picture-gallery.

During this early period, some attempt was made to take account of the individual culture of each of the peoples, and the local language. Teaching was in the native tongue and adapted, where necessary, to the nomadic way of life by means of seasonally mobile schools held in wigwams or tent shelters.

The Soviet period: the imposition of Communism

The early measures were not in place long enough even to demonstrate how useful they were. Where they were not simply abandoned altogether, they were corrupted into something unrecognizable following the victory of the political radicals who imposed – from that time right up to the end of the Soviet era – their own views of how the indigenous peoples of Siberia were to be transformed, and what they were to become, in order for them to be conformable Soviet citizens.

Accordingly, the collectivization of the means of (food) production began in the 1930s and took ten years or so to be fully applied. The process saw the abrupt confiscation of farming families’ livestock, which then became the property of the state and were the responsibility of the large cooperatives, the kolkhozes. Nomadic groups were obliged to settle and become residential, at least outwardly. Those who complained the loudest about collectivization were summarily deported – as on principle were the owners of the largest herds of reindeer. The shamans, around whom native Siberian society pivoted, were outlawed for being mere ‘parasites’.

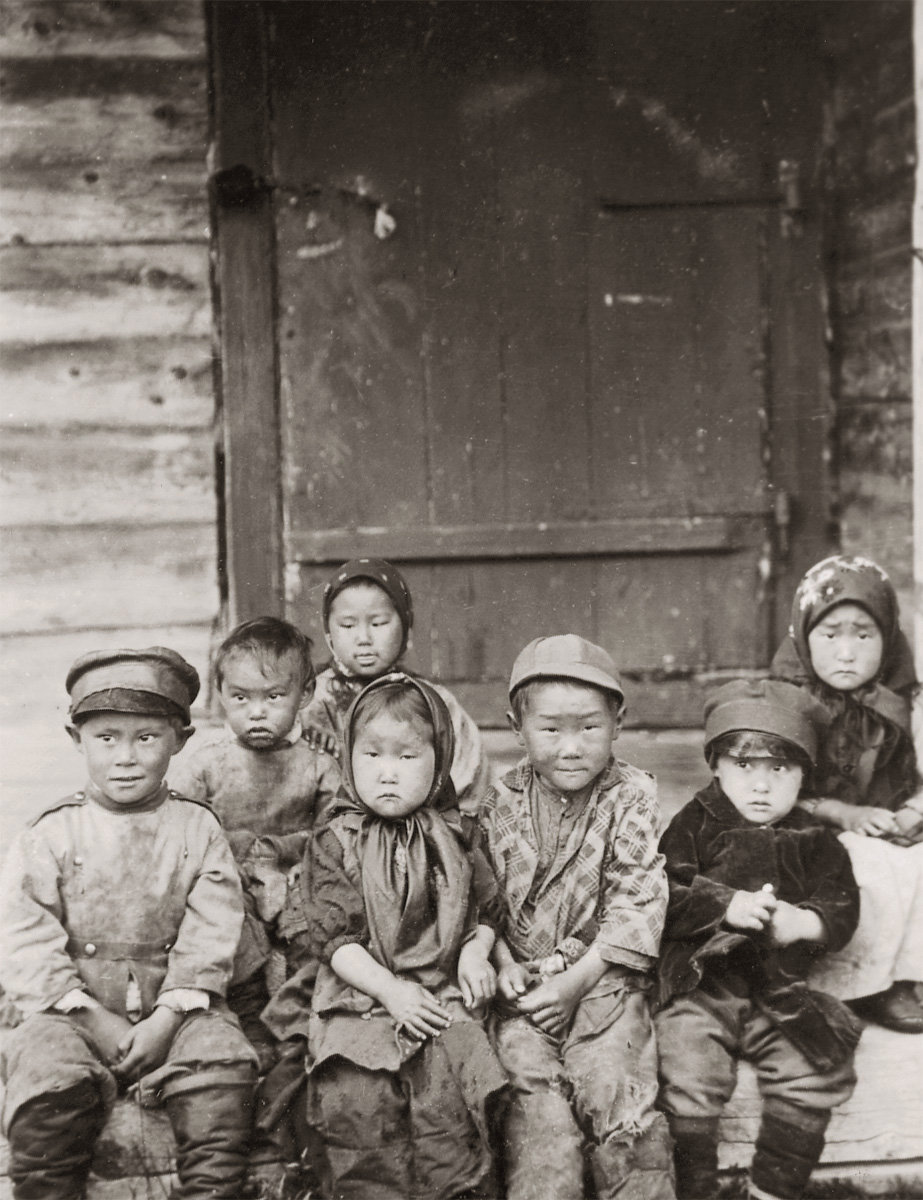

Simultaneously, the standardization of education and the boarding-school system became a highly effective tool in the policy of forced assimilation to the Soviet lifestyle. For the long months of the school year, the children of nomadic groups and from isolated villages were separated from their families and confined in multi-ethnic establishments under the control of Russian-speaking cadres. They were forbidden to speak in their native tongues, and the education they received was different from what they would have learned in their traditional backgrounds. When they came to leave their boarding-schools, each generation of students found itself at odds with parents and relatives, unable to find a place in what had once been home, knowing nothing about the ancestral way of life … and incapable of living in the manner best suited to the taiga or the tundra. In the space of just a few years, the precious practical knowledge transmitted from generation to generation for centuries on end was deliberately obliterated.

The increasing marginalization of the aboriginal ethnic groups of Siberia, in the light of the value of the territory’s natural resources, could not but reinforce the process of assimilation. From the 1930s, moreover, drawn there by special concessions and benefits, hundreds of thousands, and finally millions, of Soviet migrants flocked into the northern regions where they added to the already abundant manpower within the camps of the Gulags. The flow of migrants actually intensified as the Soviet era came to an end.

During the 1960s, under Nikita Khrushchev, there was a campaign to close the ‘little villages with no prospects’ which came to a head at the very same time that the local cooperative kolkhozes were redesigned and streamlined as the much larger sovkhozes (state super-farms). Much of the original populations, against their will, were turfed out of their ancestral lands and forcibly relocated in small progressively-minded urban centres otherwise full of Russian-speakers. Those uprooted in this way commonly felt stifled in these new surroundings, but the effect was undoubtedly yet again to speed up the process of ‘natural’ assimilation – especially as people had to communicate with each other and the TV programmes were all in Russian. Inevitably, intermarriage between Russian-speakers and young people of different ethnic background became fairly widespread.

But there was an even more vexatious consequence of the industrialization of Siberia and the influx into the northern and eastern regions of massive numbers of immigrants: environmental destruction. The list of ruinous effects is long – deforestation in the most easterly zone and on the Pacific coastline; pollution of rivers and lakes (the Ob, the Yenisey, the Vilyuy, Lake Baikal, and so on); acid rain (the High Altai, the area around Lake Baikal); air pollution (Norilsk, the Kuzbass Basin, Magadan, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk); and more. Such forms of pollution of course hit first and hardest the local populations who lived almost exclusively on natural produce in the affected areas. The spoiling of pasturage similarly led to an immediate reduction in the numbers of livestock and reindeer. Places where the hunting was known to be good suddenly became much smaller – and much emptier once the poachers had got there. Fish became scarce, and those that were caught might often be dangerous to eat.

After Communism, poverty

The economic stagnation which followed the break-up of the Soviet Union bore directly upon the minority groups of the Siberian north. All the advantages they had become accustomed to disappeared overnight, causing a significant downturn in the quality of life. The ethnic communities were suddenly out on their own – seventy years too late. No more motor-fuel, no more helicopters to the rescue and even many of the ordinary social services could no longer be relied on. Healthcare deteriorated to the extent that the mortality rate once more increased sharply, notably through the ravages of (potentially curable) tuberculosis. Living conditions in the north became severe – so much so that women were no longer willing to accompany men into the taiga, far less the tundra, and the number of marriages plummeted, as did the birth rate correspondingly.

The loss of a sense of tradition, the uprooting of cultural identity, uncertainty over the future and overall poverty are factors easily understood as leading towards self-destructive tendencies which, in this case, often translated into an addiction to alcohol. In the villages of the north, therefore, one commodity that is never likely to run out is vodka, even though its price rises steeply at night-time and on pay-days. The suicide rate has soared, and fatal accidents linked in one way or another with drunkenness are now nothing out of the ordinary. Indeed, life expectancy for ethnic peoples in Siberia – less than 50 years for men – is the lowest in all of Russia.

The will to live: renewal

This sombre picture nonetheless contains a tiny speck of optimism subsumed in the single word renewal. Since the 1970s, many of the different communities in Siberia have discovered among themselves writers, poets and artists, all intimately concerned with the catastrophic fate of their fellow aboriginals, and all refusing to admit even the possibility of their own ancestral culture’s extinction. They include people whose names are today well known, such as Vladimir Sanghi (of the Nivkhi), Yuri Rytkhe (Chukchi), Anna Nerkagi (Nenets), and the Kurilov brothers (Yukaghirs).

At the advent of Perestroika, such concerns bubbled to the surface and began to be expressed forthrightly, to cause people to come together to talk and to take action. It may have started among what passed for the elite, but it was soon very much the preoccupation of large sections of the whole populace. A movement for the renewal, the renaissance, of the peoples of Siberia had been born, embodied by the Association for the Minority Peoples of the North, formally founded in 1989. This association contains members representing all the minority groups of Siberia, from the far north to the extreme east of ‘Russian’ Asia, dedicated to defending the rights of the aboriginal communities, to the protection of their ancestral lands, to the furtherance of independence, to the preservation of the ethnic cultures, traditions and languages, to freedom to choose their preferred way of life. The precepts of the association are relayed throughout Siberia by a network of branches and local groups of all kinds, including folklore societies and cultural arts and crafts clubs, whose task requires considerable effort and perseverance. For many, the aim seems to be forever just out of reach, as the rehabilitation of ancestral practices would seem to depend as much on local economics. The larger ethnic groups in Siberia, such as the Yakuts and the Buryats, after all, are finding renewal – renaissance – much easier because they are generally far better organized and have their own standing institutions that benefit from an annual budget intended specifically to cater for matters of cultural heritage. (These ethnic groups are the subject of special clauses within the constitution of the local ‘Autonomous’ Republic of the Russian Federation, and have been now for 20 years.)

The realities of life for the peoples of the north today are far from simple. A good third of the aboriginal populations have become entirely urbanized and are no longer distinguishable from other members of the public. The remainder live as best they can in their rural surroundings, perhaps half-engaged in traditional activities, perhaps half doing other things or simply unemployed.

For all the pain of assimilation, and for all the traditional ancestral practices with which the younger generation has failed to become familiar, the essential contribution bequeathed to the world by the ethnic cultures of Siberia seems, nonetheless, in general, being maintained. That contribution is made up of a way of life founded directly on closeness to and dependence on nature, and on a holistic vision of the world and of humankind’s place in it, both recognizable even now in the persistence of animist rituals (or less often, shamanist rituals).

The next section of this book makes contact with such original ways of life, original ways of thinking – original, that is, in the sense both of being primeval and unlike anything else – so characteristic of the aboriginal peoples of Siberia.