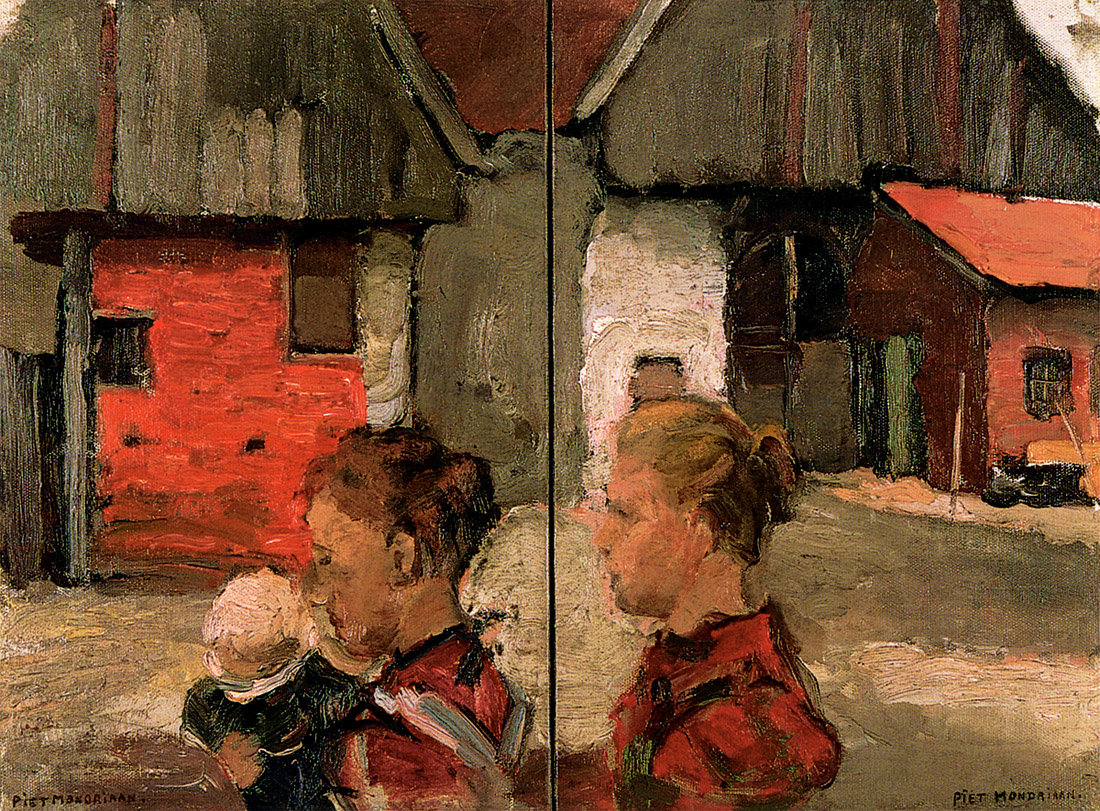

Woman with a Child in front of a Farm, c. 1894-1896

Oil on canvas, two parts, each: 33.5 x 44.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague

The Beginning: 1872-1925

By the centenary of his birth in Holland on 7 March 1872, Piet Mondrian had become a celebrated international figure. There were major exhibitions of his work in the United States and abroad, beginning with a retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in the fall of 1971.

The artist’s life and work were extolled in papers and articles published in more than 30 symposia, books, and periodicals. It is appropriate that most of these tributes originated in America, where Mondrian lived as a war refugee during the last four years of his life.

He had long held a dream of the United States as the land of the future, and designed his paintings as harbingers of a “new world image”. The image changed in America yet the theory remained basically as formed in Europe. It was rooted in Holland, as were many aspects of the artist’s personality and artistic philosophy.

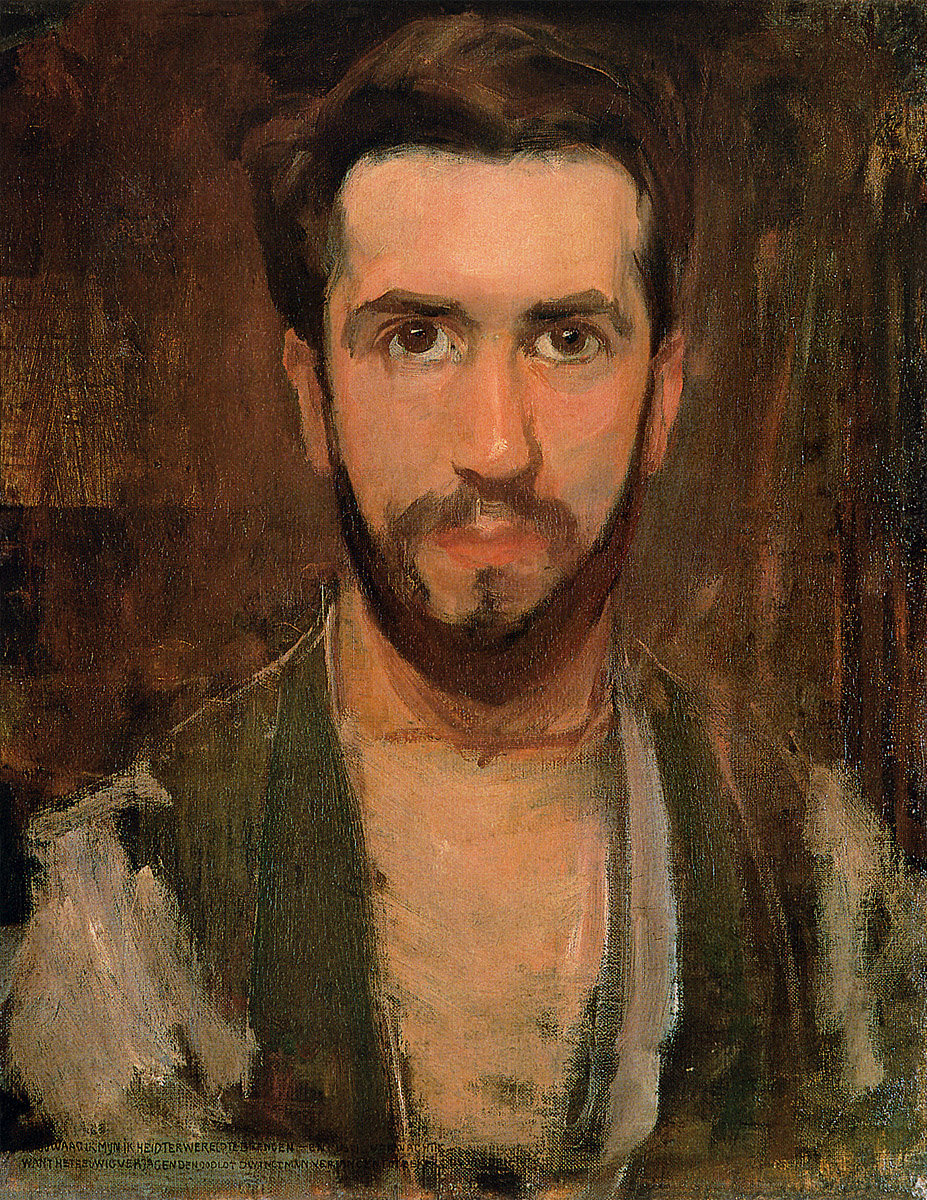

His father attained diplomas in drawing, French, and headmastership in The Hague and taught there for several years before being appointed headmaster of a school in Amersfoort. During the ten years that he and his wife Christina Kok lived there, they had the first four of their five children. They named their second child and eldest son (according to the Dutch spelling) Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan, Jr. Uncle Frits Mondriaan often visited his brother’s family when he worked in the vicinity of Winterswijk. There, and later in Amsterdam, he took his nephew on sketching expeditions into the surrounding countryside. Piet acquired technical skill from his uncle, if not his sense of composition. Any comparison of canvases by the two makes clear that the younger artist’s understanding of spatial relationships far exceeded that of the elder.

A family friend paid for young Piet’s studies at the Amsterdam Academy of Fine Art, which he attended from the ages of 19 to 22.

While he continued to paint landscapes, and occasionally sold them, Piet’s artistic interests gradually turned away from those of his father and uncle. He became less and less a realist and, while he continued to use the same painterly strokes as before, the young Mondrian began to heighten his colour, influenced by Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works brought back by friends from Paris.

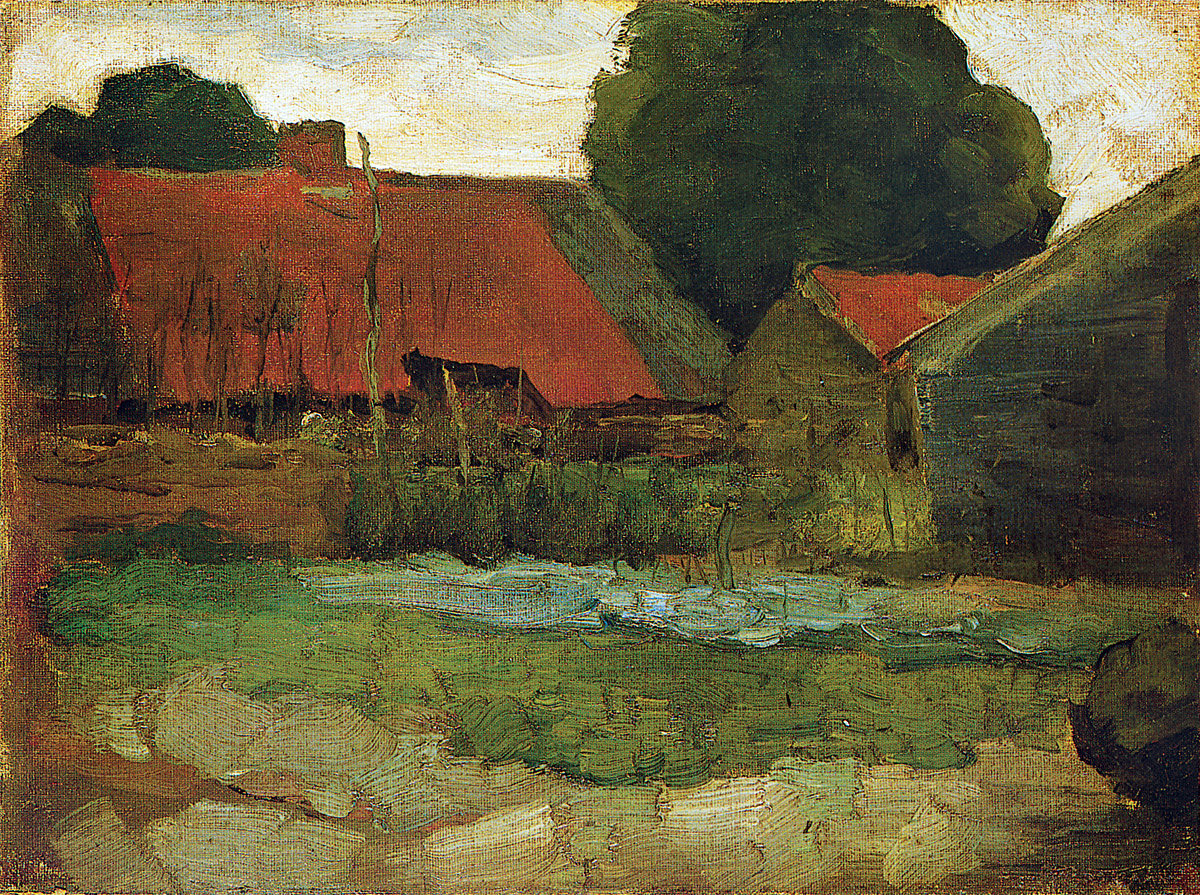

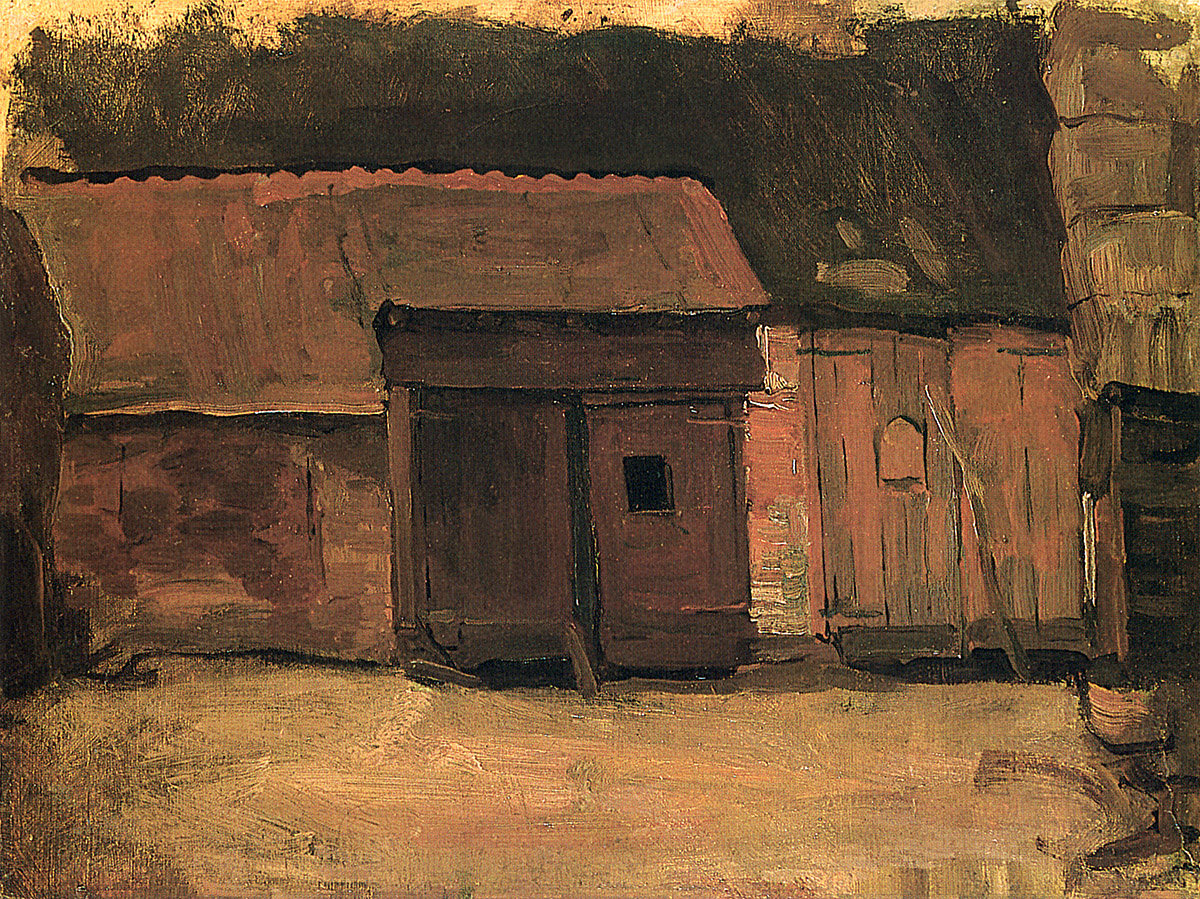

Farm with Line of Washing, c. 1897

Oil on cardboard, 31.5 x 37.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague

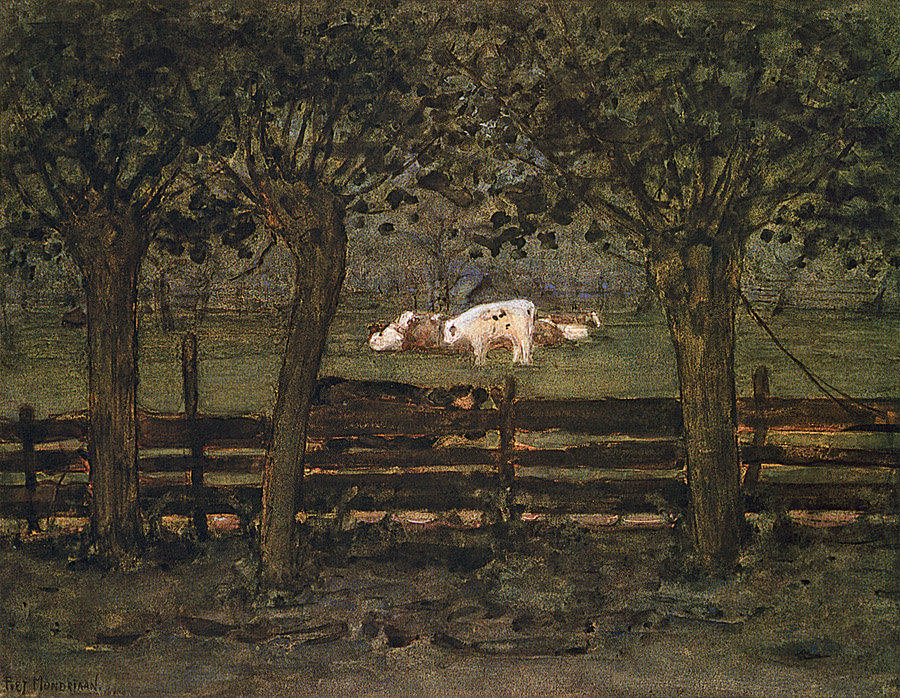

Farm on a Canal, 1900-1902

Oil on canvas laid down on panel, 22.5 x 27.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague

The artist explained his transitional work of this time by saying that he had “increasingly allowed colour and line to speak for themselves” in order to create beauty “more forcefully… without verisimilitude”.

Through consistent abstraction, he realised that the straight line had greater tension than the curved line and could therefore express a concept like vastness better than a natural line. He had been so inspired by the French Cubist paintings exhibited in the fall of 1911 in Amsterdam, that he left for Paris the following spring in order to confront their sources more directly.

The artist was thoroughly committed to Picasso’s and Braque’s theory of Cubism. Mondrian worked to suppress the solids and voids of natural subjects in favour of their flat, geometric equivalents.

The elements were no longer identifiable as belonging in nature yet were still vaguely natural in form and colour. This equivocation brought him to a turning-point:

Gradually I became aware that Cubism did not accept the logical consequences of its own discoveries; it was not developing abstraction toward its ultimate goal, the expression of pure reality…

Mondrian lived in Paris for two years before he was called home in 1914 by the illness of his father.

He expected to stay in Holland only a fortnight, but World War I erupted while he was there and the Dutch borders were closed. This forced him to remain for five years. What seemed at first a depressing turn of events, however, became a fortunate hiatus. During the years 1914 to 1919 he met several other painters, sculptors, designers, architects, and writers who were either native to the country or found themselves in it because of war.

Of greatest importance to the artist’s development was Theo van Doesburg, who proposed that artists who were willing to sacrifice their “ambitious individuality” should form a “spiritual community” around a periodical published under the name De Stijl [‘Style’].

The artists whom van Doesburg drew into his plan came from what he called “the various branches of plastic arts”. They pledged to search for the logical principles in each of their art forms that would meld with those of their colleagues to form a “universal language” of art, or “style”. The result would be both an artistic style and an aesthetic lifestyle. By 1917, when he began to write essays for van Doesburg’s publication, the artist had established his theory intellectually.

Truncated View of the Broekzijder Mill on the Gein, Wings Facing West, c. 1902-1903 or earlier

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard, 30.2 x 38.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

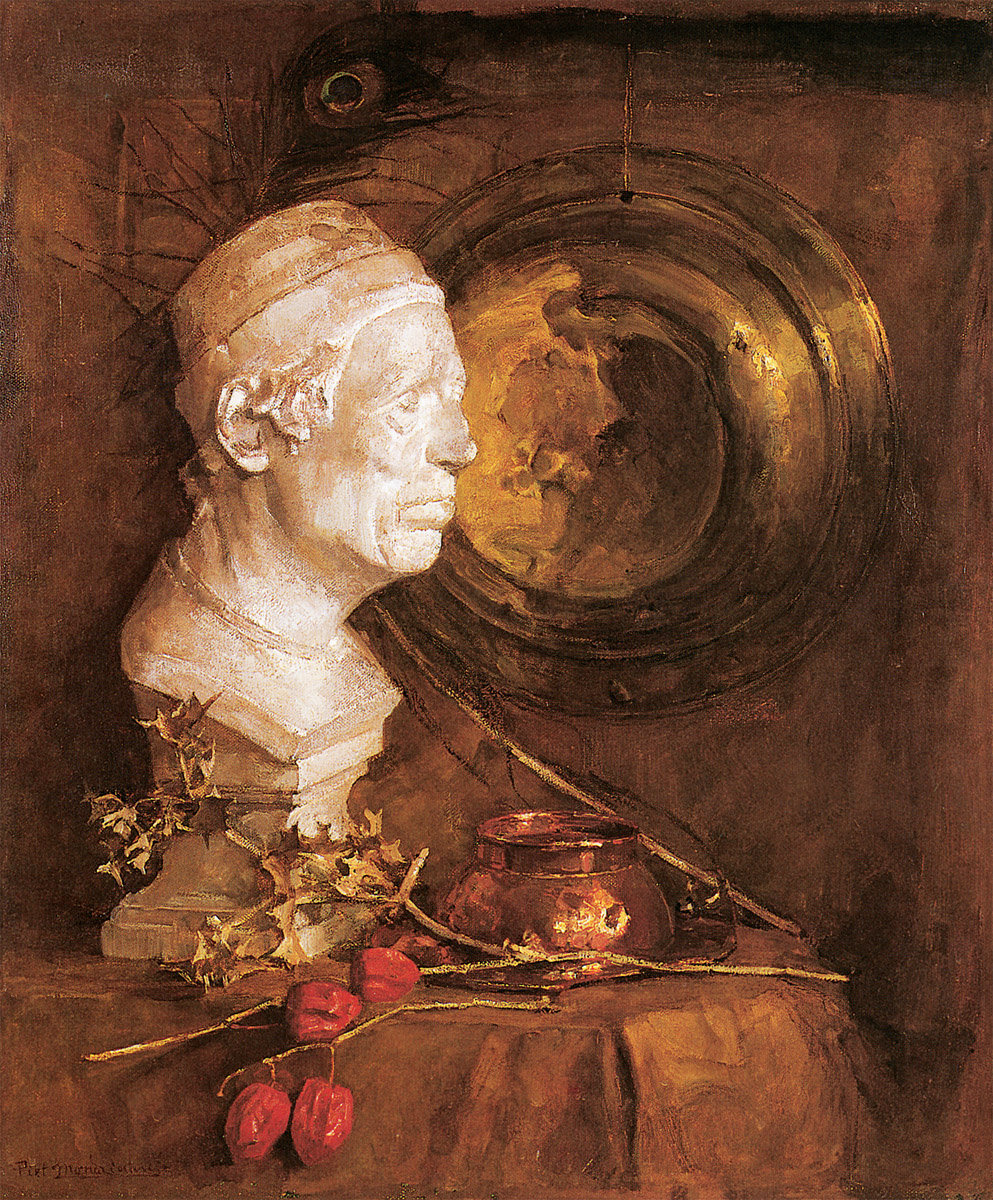

Still Life with Plaster Bust of G. Benivieni, 1902-1904

Oil on canvas, 73.5 x 61.5 cm. Groninger Museum, Groningen

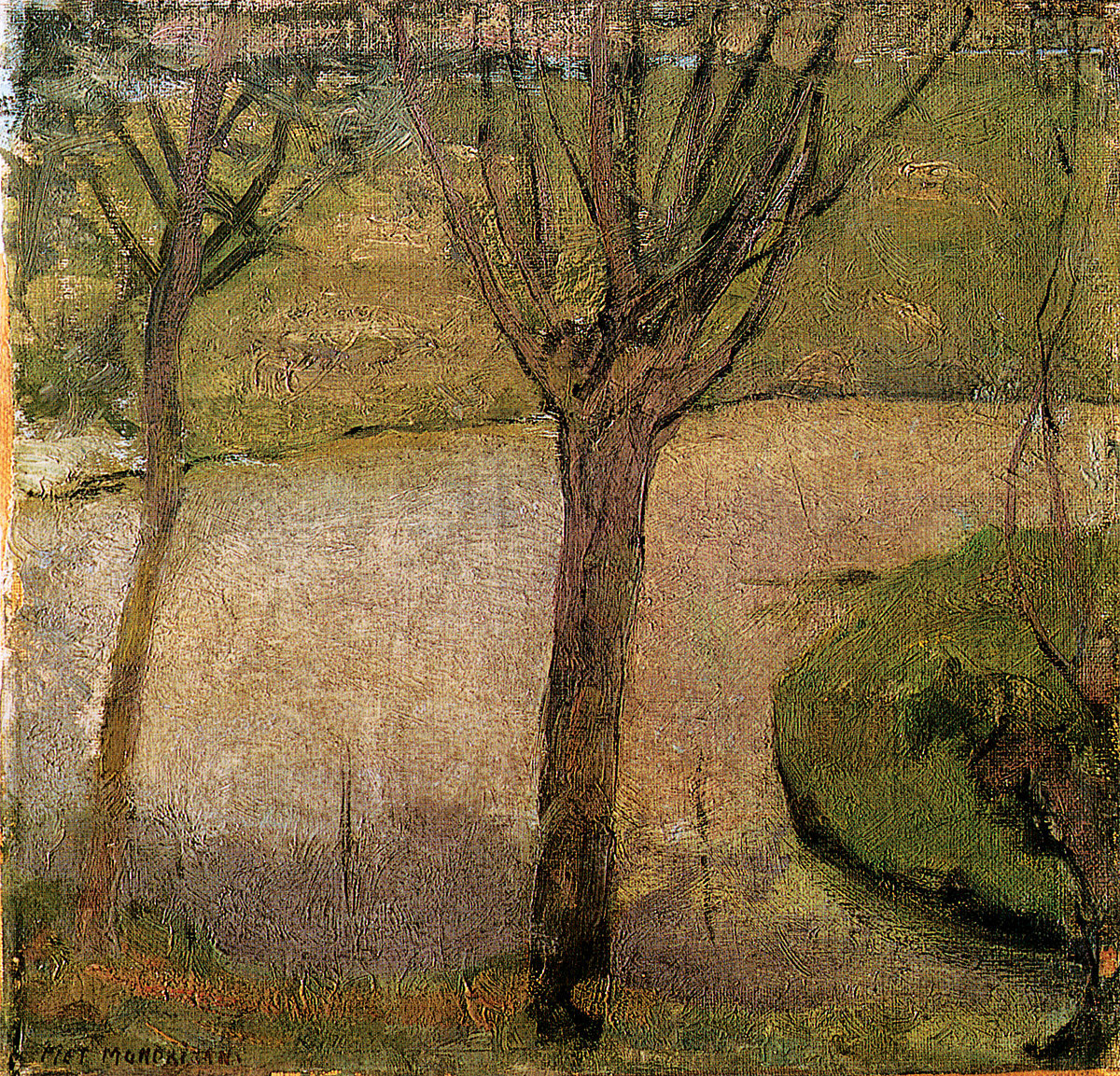

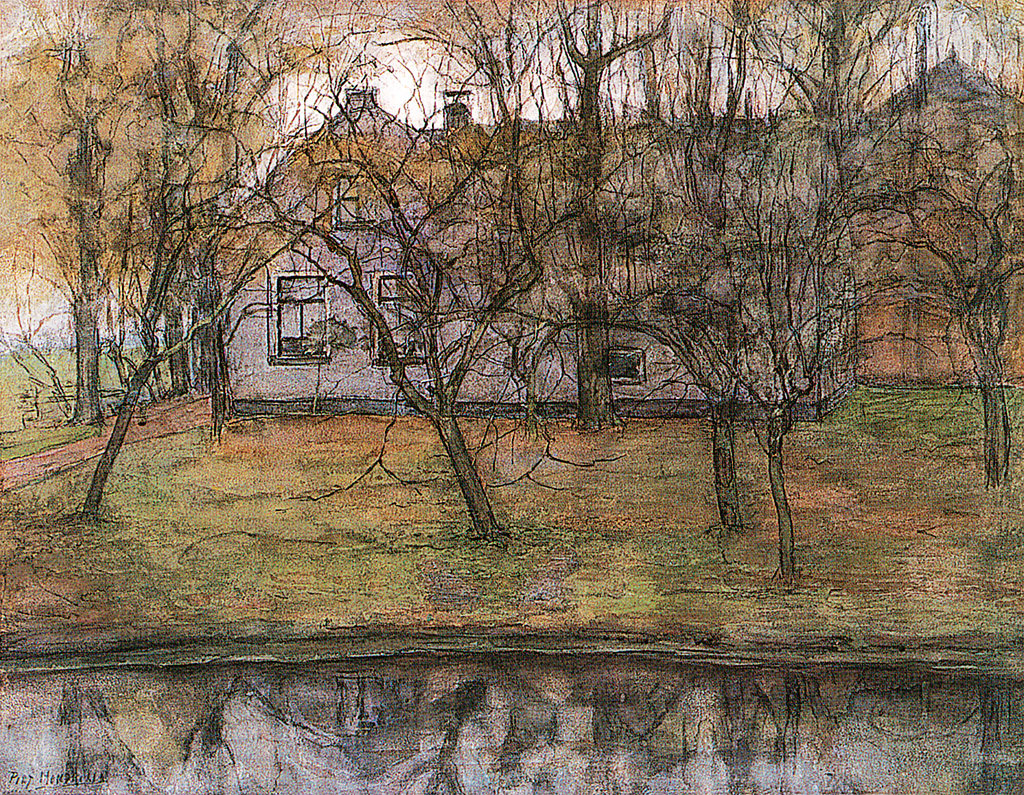

At the Lappenbrink, Winterswijk, c. 1904

Canvas laid down on board, 33.5 x 45 cm. Private collection

In paintings of 1916 and 1917, such as an unfinished Composition in Line, Second State, the Composition in Colour A, and Composition in Colour B, Mondrian first succeeded in separating line and colour, as elements, from the motifs of a church façade and the sea and pier of Domburg.

The last paintings he completed in Holland and the others done after he returned to Paris in 1919, through the first two or three years of the 1920s, represent successive attempts to define the new image visually.

Mondrian carried the paintings through various stages in which, at first, he turned the elements into uniform planes coloured in muted versions of the primaries. He separated the planes so that they seemed to float against a white background, but concluding that this effect was still too “natural,” he then connected the planes in a regular grid, covering either a rectangular or a diamond format.

While the planes were still connected, in the next phase the artist made them larger and unequal in size and coloured them in primaries or in values of black, white and grey. He attenuated the black planes to make them extend alongside the coloured and non-coloured planes. The blacks then served as structural bars holding the other planes together while at the same time making them more discrete. Like the canvas, the smaller rectangles or planes represented both form and space.

The colours of these planes stood for the intensities and values of nature, cleansed and rendered to their primal colour states – red, yellow, and blue and primal non-colour states – black, white, and grey.

Black planes performed multiple roles. In addition to their non-colour function, they were structural, determinate, and active. By creating paths of movement for the eye, black planes also added a sense of energy.

Although the parts were important, the artist wanted always to emphasise their subordination to the harmony of the whole. Different in size and colour, they had equal value, or equivalence because of their similar nature.

Even when smaller areas of colour were balanced against larger areas of non-colour, they had the feel of equal weight, or equilibrium when the proportions were right. Composition, 1921, exemplifies the artist’s principles at work.

So that there could be no confusion with the usual implication of space receding behind the frame, Mondrian had mounted the canvas on the frame, thereby projecting the painting’s actual space into the room.

Working, therefore, in the “manner of art,” Mondrian had created a “new structure” that, in contrast to life, was “exact”: the fact that it was “real” did not mean that the painting was a material thing only – actually, the artist associated the reality of the work with a super-reality or universal ideal.

Here was the artist’s ultimate duality – an object seemingly devoid of life, yet conceived as life itself – not in the sense of a deficient or incomplete fragment but a finite particle that contains within its structure the promise of its infinitude. By creating this particle of life, Mondrian had not illustrated pure reality or pure beauty. He had made the painting be that reality. He had thus presented art in its most vital form, and life in its most unified form.

As Mondrian stated succinctly, “Unity, in its deepest essence, radiates: it is… Life and art must therefore be radiation”.