Mikhail Vrubel, The Six-Winged Seraph, 1905. Watercolor, lead mine and black chalk on paper, 33.6 x 48.5 cm. Pushkin Museum, St. Petersburg.

THE WORLD OF ART BY VSEVOLOD PETROV

In the history of Russian art, the late nineteenth century was a period of creative innovation and a fundamental restructuring of form.

In the 1890s, a new chapter was opened in the visual arts by a generation of artists who radically revised almost the entire range of established tradition. Authorities that had seemed immutable were suddenly toppled from their pedestals. The horizon of artistic creativity broadened, a new aesthetic emerged, and new trends arose, all in striking contrast to what the earlier art movements of the nineteenth century had propagated. The revaluation of values led to cardinal changes in the interpretation and understanding of creative objectives and techniques.

In all these processes, a preeminent, if not definitive role was played by the artists and art critics grouped around the journal Mir iskusstua [The Golovin]. However, in order to properly assess the historic significance of the artistic, educational, and organizational activities of that group, one must at least briefly review the general state of fin de siècle Russian art.

By that time academic painting was no longer the progressive factor, it had once been. However, due to governmental backing it continued to thrive exclusively as a reactionary trend serving the purposes of official art.

A crucial role in the reshaping of Russian art during the last quarter of the nineteenth century was played by members of the Society for Itinerant Art Exhibitions (the Peredvizhniki or the Itinerants). Having achieved remarkable results in the 1870s, the Itinerants reached their peak in the 1880s. Genuine masterpieces appeared at practically each of the traveling exhibitions. At that time Vasily Surikov produced the Morning of the Execution of the Streltsy, Menshikov in Beriozou, and Boyarina Morozova. Ilya Repin painted his Religious Procession in Kursk Province, They Did Not Expect Him, and many of his best portraits. A number of other well-known painters also took part in the society’s activities.

By the 1890s, having fulfilled their highly creditable social and historical mission of releasing progressive Russian painting from the shackles of the antiquated academic tradition and having developed a consistently realist method, the Itinerants had ceased to be innovative and were in danger of coming full circle.

Yet the creative potential that the Itinerants had introduced with their new approach was far from exhausted. In the 1890s, several of the younger painters represented at traveling exhibitions displayed superlative talent and largely contributed to the realist trend. One must inevitably mention Sergei Korovin’s Village Community Meeting (1893), which was shown at the 22nd Itinerant Exhibition, Nikolai Kasatkin’s Poor People Gathering Coal at a Worked-Out Pit and his study, Woman Miner, both done in 1894 and displayed at the 23rd Itinerant Exhibition, and, finally, Sergei Ivanov’s study of prisoner life that figured at the 28th Itinerant Exhibition. Each of the artists named built on those particular pieces to produce an extensive cycle of paintings.

Thus Sergei Korovin dedicated himself to the traditional Itinerant theme of peasant life, furnishing a probing reflection of the Russian countryside with the acute social problems that followed the abolition of serfdom in 1861.

Like Korovin, Sergei Ivanov originally concentrated on the peasant theme. In the 1880s, he produced a series of pictures about migrant peasants who had abandoned their native lands and trekked to Siberia in search of a better life. Later, in the 1890s, he embarked on a new cycle which portrayed life in prisons, stockades, and labour camps. Thematically, this cycle was particularly relevant during the period of political reaction under Tsar Alexander III with its surging tide of popular unrest. As Ivanov’s biographers rightly noted, for him this cycle served as a prelude for that subject matter which was to gain prominence in his work at the time of the first Russian Revolution (1905-07).

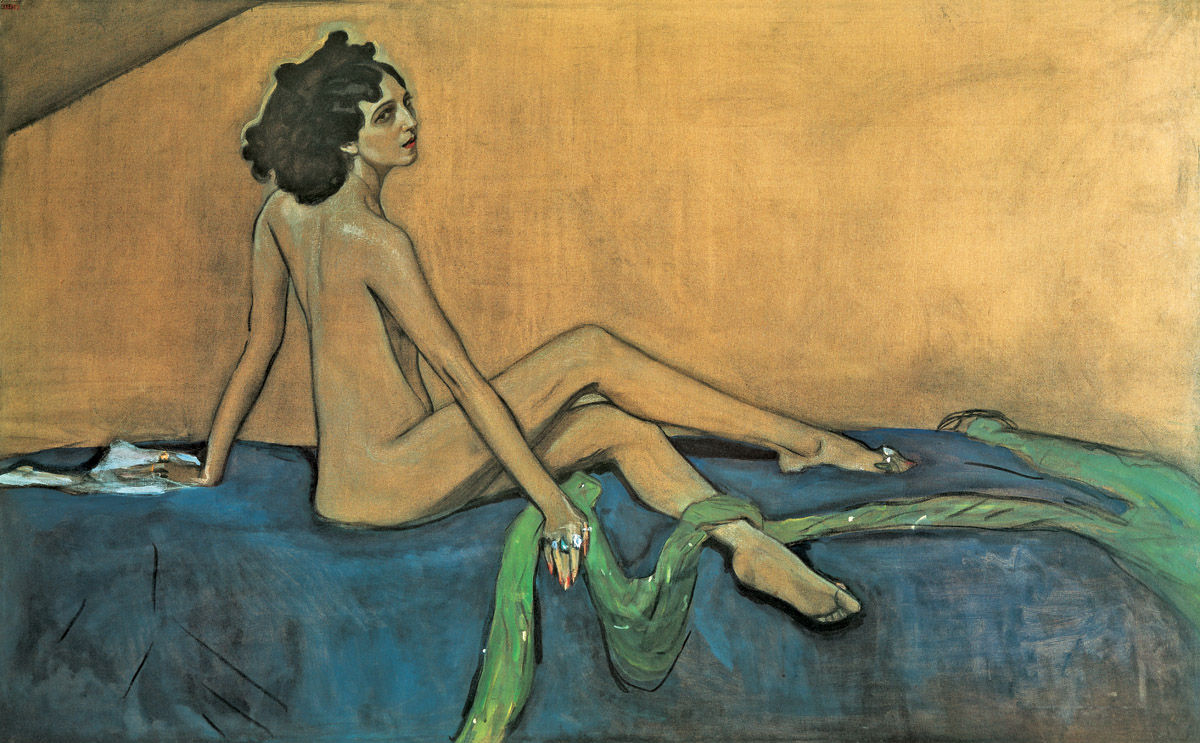

Valentin Serov, Portrait of Ida Lvovna Rubinstein, 1910. Tempera and charcoal on canvas, 147 x 233 cm. The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

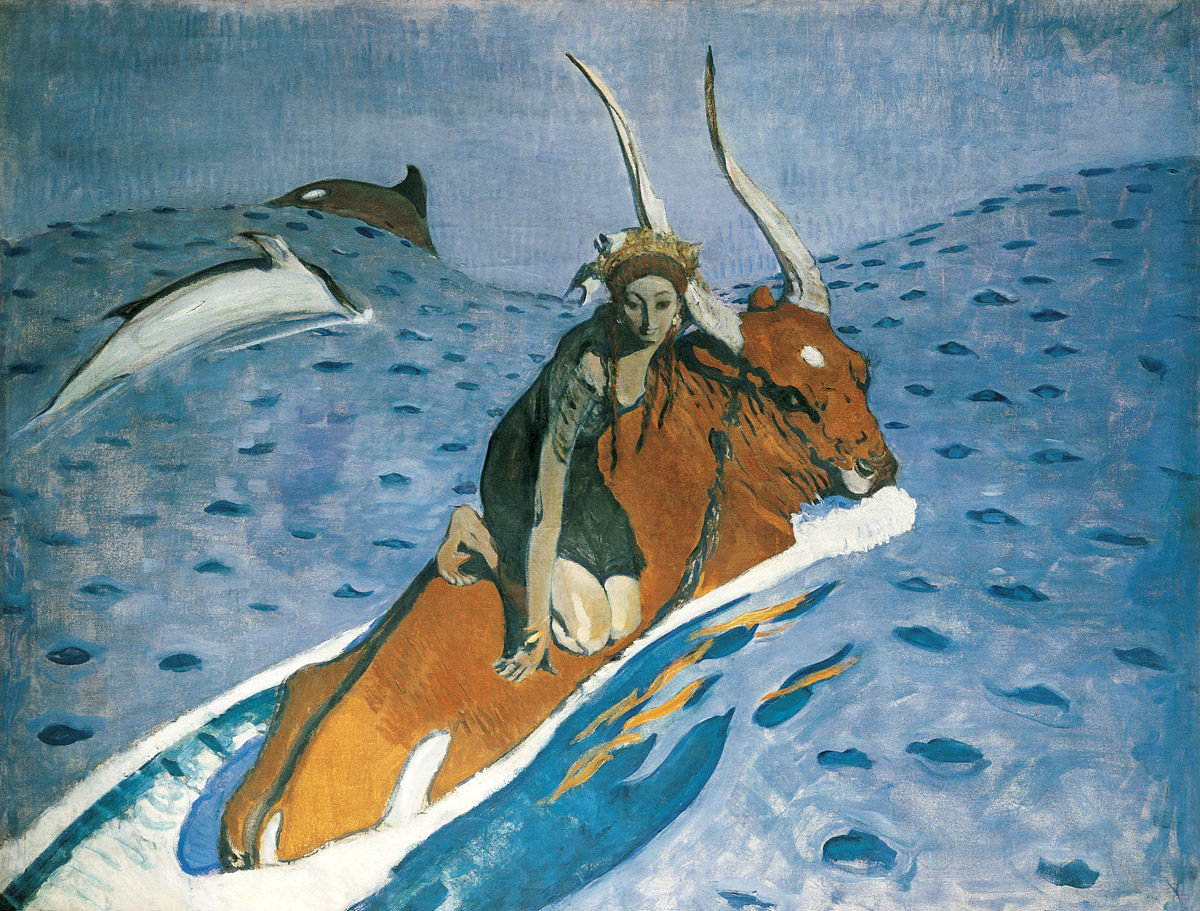

Valentin Serov, The Rape of Europa, 1910. Oil on canvas, 71 x 98 cm. The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

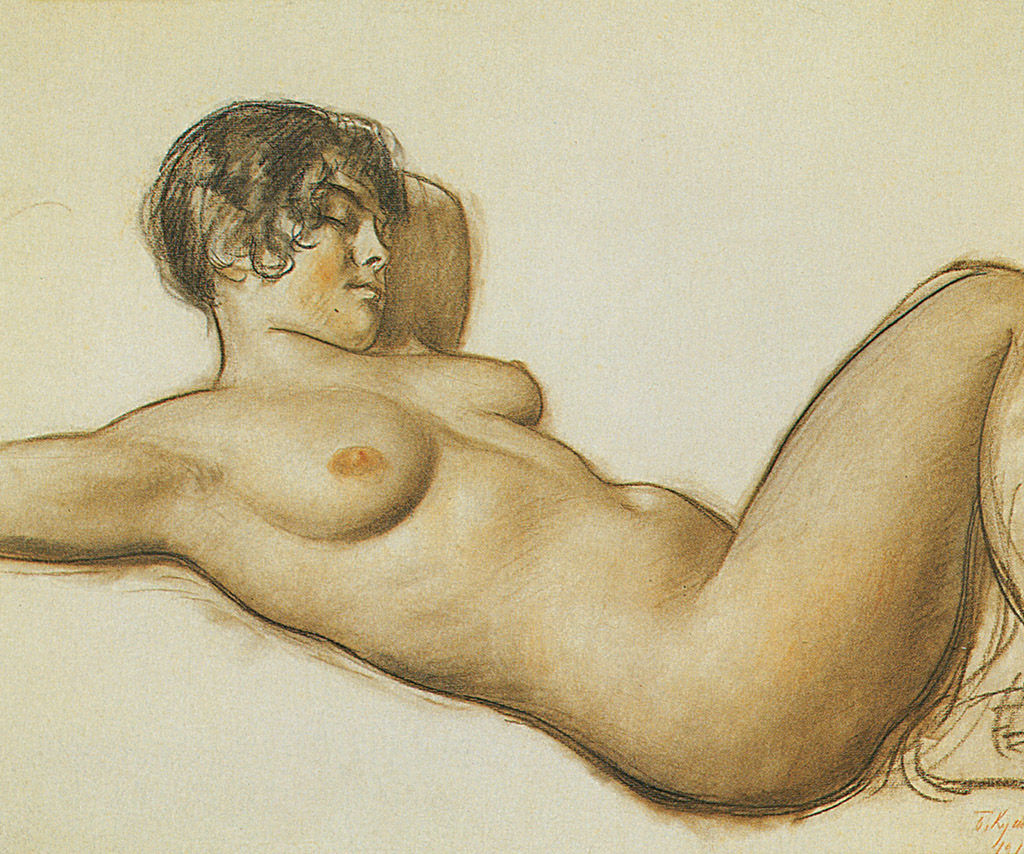

Boris Kustodiev, Reclining Model, 1915. Charcoal, sanguine, and colored pencils on paper, 47 x 57 cm. Brodsky Memorial Museum, St. Petersburg.

Nikolai Kasatkin went even further than his fellow Itinerants. He was the first among Russian painters to derive his themes and images from the life of the newest social class in Russia, the industrial proletariat that had emerged at the turn of the twentieth century. The two works already mentioned marked the beginning of the artist’s extensive Miners cycle. The key painting of this cycle, Coal-Miners on Shift (1895), was shown at the 24th Itinerant Exhibition. The entire cycle had nothing of the Populist sentimentality so characteristic of the later genre paintings by the Itinerants.

Be that as it may, such artists as Sergei Korovin, Sergei Ivanov, and Nikolai Kasatkin did not set the tone for the traveling exhibitions of the 1890s. Among the later Itinerants the dominant role was shared by landscape painters, who imitated Isaac Levitan and Arkhip Kuinji, as well as genre painters the basic content of whose work was a “dull, routine reality, unmarked by highlights or powerful, captivating emotionality had become the constant overall theme of the traveling exhibitions.”

The traveling exhibitions arranged in the 1890s presented hardly anything comparable with the masterpieces of the previous decade. Now epigones were in command.

In the 1880s, at a time when the Itinerants appeared to hold undivided sway, the earliest signs of a barely noticeable revitalization of art were already there. Mikhail Vrubel, a painter of genius, began his artistic career. Konstantin Korovin displayed his brilliant talents. Novel lyrical intonation sounded in Isaac Levitan’s landscapes and in the pictures of the young Mikhail Nesterov. The twenty-year-old Valentin Serov painted his famous Girl With Peaches (Vera Mamontova), the first gem in the output of the gene ration that was destined to replace the Itinerants.

These artists, with the exception or Vrubel, participated in the traveling exhibitions mounted in the 1880s and 1890s, even though they far from fully shared the ideological and aesthetic concepts of the Itinerants.In reality, they were in many ways alien to the Itinerants. Small wonder that in his reminiscences Nesterov dubbed himself and his fellows the “stepchildren of the Itinerants.” They were becoming convinced that the day of the Pereduizhniki in Russian art was done and that the succeeding generation would have to search for new roads.

The Itinerant philosophy was even more categorically rejected by the progressive younger generation of artists who made their appearance in the 1890s. Igor Grabar, a budding painter who developed into a prominent artist and art historian, noted in his My Life: An Automonograph:

“At first Korovin, Serov, Maliutin, Vrubel, Arkhipov, Ostroukhov and Levitan, and, after them, we the junior generation... came to realize that the way of Miasoyedov, Volkov, Kiseliov, Bodarevsky, and Lemokh [Itinerant epigones] was not our way, and that even the best Itinerants were fundamentally alien to us... We accepted only Repin and Surikov as understandable and close... We sought a greater dimension of truth, a more subtle understanding of nature, less convention, extemporization, less crudity, journeymanship, cliche...”

The younger generation’s rebellion against the authority of their seniors, a typical “fathers-and-sons” conflict, sprang from the general conditions within which Russian social thought evolved at the turn of the twentieth century.

The Populist phase had given way to the new, proletarian period of the Russian liberation movement and the Itinerants’ decline was a symptom of the hopeless crisis and degeneration of the Populist ideology. The dawn of the twentieth century brought with it new social, moral, and aesthetic problems. However, for most Russian artists of the time, the process of creatively assessing its realities was an agonizing effort.

The increasingly complex conditions of the Russian art scene called for a new grouping of forces. One relevant manifestation was the appearance of the Abramtsevo Circle, an unofficial group of artists drawn together by the well-known Moscow art patron and social figure Savva Mamontov and named after his suburban estate. They included some of the major Itinerants, such as Ilya Repin, Vasily Polenov, and Victor Vasnetsov, who sympathized with the progressively minded younger generation, but the dominant role in the circle was played by Konstantin Korovin, Valentin Serov, and Mikhail Vrubel. This young trio was instrumental in forming that creative atmosphere largely stripped of the superannuated populist dogmas of the latter-day Itinerants. The work of the circle’s members reflected certain substantial novel tendencies that were subsequently carried forward in early twentieth-century Russian art.

In 1885, Sawa Mamontov established his private opera company in Moscow, enlisting many prominent artists to work as production designers. This laid the foundation for a new type of stage decor that had nothing in common with traditional stereotypes.

Likewise in Abramtsevo, Mamontov organized workshops to revive the techniques and forms of Russian folk arts and crafts. Artists such as Vrubel and Golovin worked there, realizing their innovative concepts.

However, the Abramtsevo Circle proved unable to develop the novel forms of creative, educational, and exhibitional activity which Russia’s visual arts so badly needed.

Somewhat later this task fell to the group associated with theGolovin. By shaping new artistic forms, the members of this group brought new ideas, aesthetic concepts, and creative principles to the Russian visual arts. Although organizational problems seemed less important to them, such matters were also among their priorities.

The Golovin group, which gave rise to a forceful influential movement, formed in St. Petersburg in the early 1890s. Its nucleus comprised several young students, former members of the Society for Self-Education. This small, select circle was dominated by Alexander Benois, subsequently to gain fame as an artist, critic, and historian; Konstantin Somov, an Academy of Arts student, a future painter and graphic artist; Dmitry Filosofov, who later developed into a writer; Sergei Diaghilev, a gifted musician, who achieved renown as an art critic and illustrious impressario; and Walter Nuvel, a budding music critic. They were soon joined by another two young artists: Lev Rosenberg, better known by his pseudonym — Leon Bakst, and Yevgeny Lanceray. By virtue of their versatile talents and high cultural standards, the group was soon engaged in extensive activities that greatly affected the artistic life of the country.

The driving force behind many of the Golovin’s activities was Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929), who combined a sensitive understanding of art with unquenchable energy and rare determination. In fact, he had a greater flair for assessing the artistic developments of the time than any of his fellows. His basic motivation stemmed from the firm conviction that Russian art had a role of global significance to play. He set himself the goal of uniting the finest Russian artists, of helping them to make their way into the European art arena, and, generally, as he himself put it, “of exalting Russian art in the eyes of the West.” He dedicated himself wholeheartedly to this objective, pursuing with persistence and fortitude, and capably surmounting every hurdle along the way.

In 1898, in St. Petersburg, Diaghilev organized an exhibition of Russian and Finnish artists, at which, for the first time, young painters came out in a united front against dreary Academy traditions and the vestiges of obsolescent trends. Diaghilev’s St. Petersburg group of Somov, Bakst, Benois, and Lanceray formed a close alliance with prominent Moscow painters, including Vrubel, Levitan, Serov, Konstantin Korovin, Nesterov, and Riabushkin. The Finnish section of the exhibition was dominated by the works of Akseli Gallen-Kallela and Albert Edelfeldt. This broad association, much greater than the original circle, served as the point of departure for Diaghilev to found the art journal which would become the ideological rallying center for early twentieth-century Russian art.

The Golovin journal came out for six years from 1899 to 1904. It was edited by Sergei Diaghilev, assisted by his entire St. Petersburg group. In 1901, Igor Grabar associated himself with the journal, eventually turning into one of the most industrious and influential art critics of the time. Diaghilev and his colleagues mounted annual exhibitions bearing the same name as the journal in which many innovative artists from both St. Petersburg and Moscow were invited to participate.

However, it was invariably Diaghilev’s St. Petersburg group of Somov, Benois, and their closest companions whose paintings and graphic works formed the core of these exhibitions. They were responsible for shaping that original art movement which has long been known as the Golovin. In the following pages, we shall attempt to describe the salient features of this movement, its aesthetic stance, creative concerns, and pictorial principles. However, it must be most emphatically stressed that none of the exhibitions or educational activities of the group were confined to any single creative trend. The Golovin cannot be properly understood in isolation from the extensive range of diverse phenomena making up early-twentieth-century Russian art.

In other words, the history of the Golovin movement can be viewed from two separate, though interconnected, angles. On the one hand, it is the history of a creative trend evolved by a St. Petersburg-based group of artists under Benois and Somov. On the other hand, it is also the history of an extensive cultural and aesthetic movement that drew within its orbit a number of prominent Russian artists whose work developed independently of the St. Petersburg group, and whose aesthetic concepts and pictorial language were at times miles apart. The Golovin movement extended not only to painting and graphic art, but also embraced several related fields, markedly affecting Russian architecture, sculpture, poetry, ballet and opera, as like as art criticism and historiography.

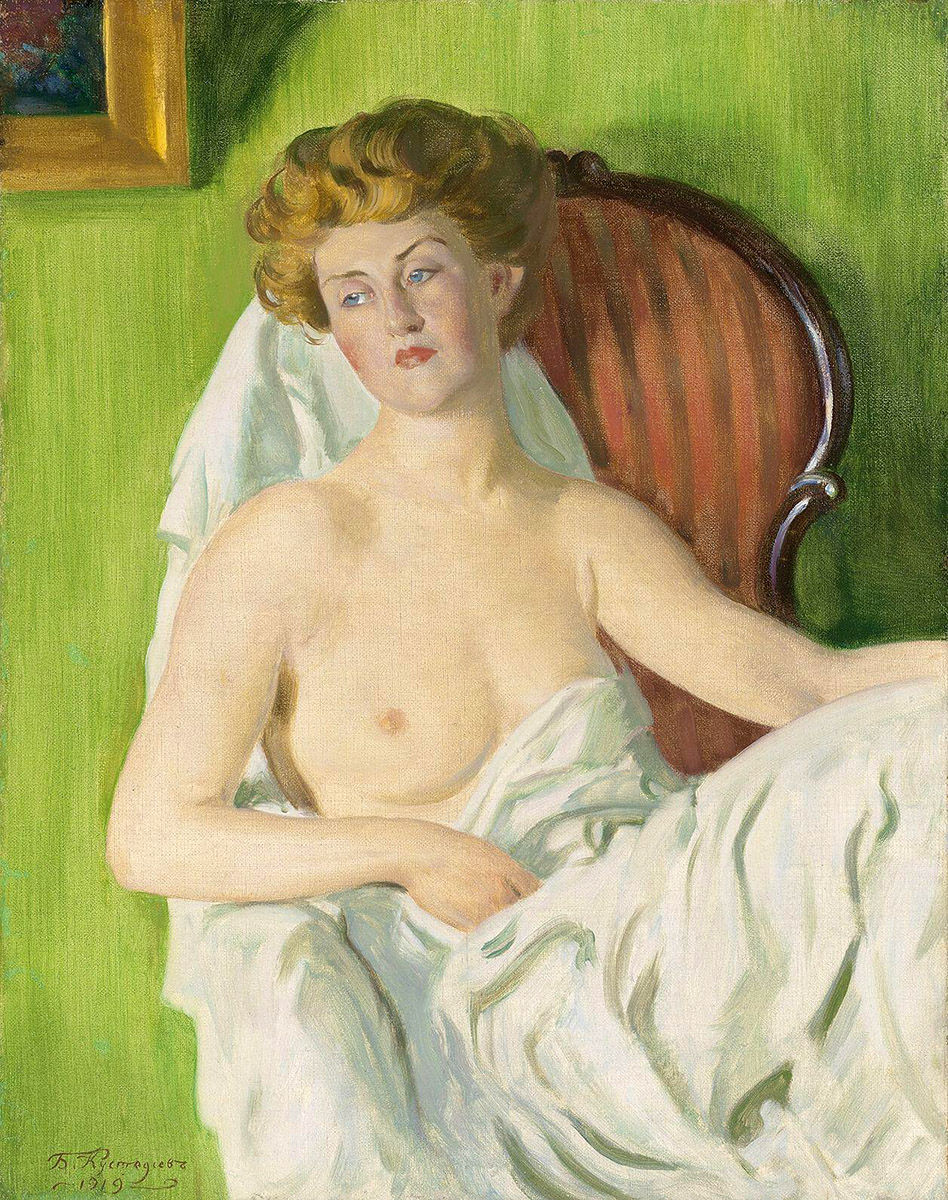

Boris Kustodiev, Portrait of the Actress Nadezha Komoroskaya. Oil on canvas, 25.6 x 29.6 cm. Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

Mikhail Vrubel, The Swan Princess, 1900. Oil on canvas, 142.5 x 93.5 cm. The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

The broad aesthetic views of the Golovin leaders, which were often eclectic, were especially manifest in their exhibitions. Diaghilev sought to bring under one roof outstanding Russian artists of diverse creative approaches. He failed admittedly, to recruit the major Itinerants, who were loath to break with their association. Only Repin once agreed to participate, in the Golovin Exhibition that Diaghilev mounted in 1899; afterwards he broke all ties with the Golovin, becoming its grim adversary — purely because he took umbrage at a particular article in Diaghilev’s journal which was extremely disrespectful of Aivazovsky, Konstantin Flavitsky, Konstantin Makovsky, and several other academics. Similarly abortive was Diaghilev’s brief “flirt” with the painting of Victor Vasnetsov, to whom he devoted a special issue of the journal. On the other hand, Diaghilev ably enlisted a broad following among the younger generation of artists and thus gained the backing of the cream of contemporary Russian art.

Still, many who took part in Diaghilev’s exhibitions only provisionally associated themselves with the Golovin, as there was no positive platform upon which they could unite with the St. Petersburg group. According to Grabar’s authoritative testimony, their alliance merely indicated an “abhorrence of the monstrous vulgarity of the St. Petersburg Exhibition groups [i.e. academic] and derision for the degenerate art of the once-powerful Itinerants.” Although far from everything the Golovin had to offer was viewed positively, it served as a valuable training-ground for many young artists.

This applies primarily to Mikhail Vrubel, the only painter of his generation who was to follow his own road throughout his life, a road totally unlike those of his contemporaries. However, he deeply appreciated the Golovin’s moral backing and to his dying day took part in all the exhibitions that Diaghilev organized. Nesterov, too, enthusiastically associated himself with the Golovin at the outset; however, he soon broke away, possibly repulsed by the journal’s overtly pro-Western orientation. Finally, the many Moscow painters who temporarily allied themselves with the Golovin, notably Konstantin Korovin, Abram Arkhipov, Apollinary Vasnetsov, Sergei Maliutin, Sviatoslav Zhukovsky, and Sergei Vinogradov, subsequently organized, as a counterweight to the St. Petersburg group, their own Union of Russian Artists, with its headquarters in the old capital.

More dependable supporters of the Golovin were Philip Maliavin, who took part in all of Diaghilev’s exhibitions, and Igor Grabar, who not only sent his paintings to these shows, but also contributed critical reviews and theoretical essays to the journal.

Special mention should he made of Valentin Serov, who collaborated with Diaghilev and Benois in mounting the Golovin exhibitions and also participated in them. He was a member of the unofficial editorial board that shaped the journal’s artistic policy. Serov’s association with the Golovin may be regarded as a major achievement for Diaghilev’s group. In fact, he was more than an ally; this great realist master, who was far superior to the Golovin artists in the power of his versatile talent, was aesthetically and, to some extent, creatively influenced by them, becoming indeed a full-fledged member of the “clan.” Serov, in turn, interpreted certain essential philosophical and artistic principles of the Golovin group in his painting and graphic art, exerting no small impact on his colleagues.

It would admittedly be a mistake or an exaggeration to fully associate everything Serov produced in the final decade of his life with the Golovin movement. Serov never relinquished his bond to the traditional realist painting of the nineteenth century in his innovations. Yet, the intense experimentation characteristic of his late period was largely linked with the artistic issues that the Diaghilev group sought to develop. On the other hand, in their best works, Benois and other notable Golovin artists drew heavily on Serov’s innovations.

Golovin philosophies also had a definitive impact on the creative efforts of Nicholas Roerich, who joined the group in 1910 and played a significant part in its activities in the years before the First World War and the 1917 Revolution.

Marc Chagall, The Birthday, 1923. Oil on cardboard, 30.6 x 94.7 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Léon Bakst, Downpour, 1906. Gouache and indian ink on paper, 15.9 x 13.3 cm. Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

Apart from allies and temporary associates, the Golovin naturally had a faithful following, dedicated to its aesthetic to the end of their days. These were Anna Ostroumova- Lebedeva, who came to the group in 1899, Ivan Bilibin, who joined in 1900, and, finally, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky and Alexander Golovin, who began to contribute to its exhibitions in 1903. Absolutely independent in their interpretation of the Golovin concepts, these young artists subscribed to the movement as convinced partisans and continuers of the cause initiated by Diaghilev.

In their effort to gather together and consolidate the vital forces of contemporary Russian art, Diaghilev and his associates demonstrated ample flexibility, fortitude, tact, and even perspicacity. True, they had their upsets. Thus, for a long time they ignored Victor Borisov-Musatov, although he could have been close kin in both technique and subject matter. Grabar tells us that none other than Serov himself advised Diaghilev not to invite Borisov-Musatov to participate in the Golovin exhibitions, contemptuously styling the artist’s works “cheap stuff.” By the time this attitude changed, it was too late. Borisov-Musatov had died without being acknowledged by the artists and critics who, one would have thought, should have accepted and supported him before all others. Only in 1906, when the journal had ceased publication and Borisov-Musatov was no longer alive, did Diaghilev include fifty of the artist’s works in his last exhibition, thus paying a posthumous tribute to him. Among other blunders of the group was the underestimation of Andrei Riabushkin and the slighting of the younger generation’s Impressionist endeavors.

Nonetheless, the Golovin achieved its purposes in a brief time and its activities had far-reaching consequences.

The Golovin exhibitions revolutionized the aesthetic outlook of most of Russia’s intelligentsia, serving to enhance its cultural development and to cultivate new tastes, and a new concept of art in general. This could hardly have been attained without the contribution made by Diaghilev’s journal.

The journal’s art policy was not formulated by Diaghilev alone; one must straightaway mention his prime collaborator Alexander Benois, the ideologist and theoretician of the Golovin as a trend. This highly talented man epitomized the new type of erudite artist — a rediscoverer and reinterpreter of forgotten aesthetic values — which evolved in the Golovin milieu. Two other similar figures, Igor Grabar and Stepan Yaremich, contributed critical essays to the journal, leaving a deep imprint on Russian art and, later, on Soviet art studies as well. On the other hand, Dmitry Filosofov, who had charge of the journal’s literary desk, was far removed from the art scene. Incidentally, he and his staff were mainly concerned with religious and philosophical matters that bore no relation to the range of problems tackled by the journal’s art section. Indeed, this unbridgeable dichotomy in the journal’s structure, which was plain even to contemporaries, was one of the causes of its decline and eventual closure.

The journal’s activities were by no means limited to mere declarations or a drive against the Academy of Arts and the Itinerants. Its program was more broadly conceived and was implemented with extreme vigor and persistence.

The educational activity that the journal pursued throughout all six years of its existence followed two basic lines. First, it discussed the contemporary state of the fine arts in Russia and some countries of Western Europe. Second, it systematically rediscovered for the reader various forgotten or misunderstood values from the nation’s artistic past.

Boris Kustodiev, Design for the opera ‘The Tsar’s Bride’ by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, 1920. Gouache, watercolor, paper, 33 x 58.5 cm. The State Art Museum, Samara, Russia.

Alexander Golovin, Portrait of Dmitry Smirnov as Grieux in Jules Massenet’s “Manon”, 1909. Tempera on canvas, 210 x 116 cm, Bakhrushin Theatre Museum, Moscow.

Konstantin Somov, Winter. The Skating Rink. Detail, 1915. Oil on canvas, 49 x 58 cm. Russian Museum, St. Petersburg.

Initially, the editorial board was concerned chiefly with the issues confronting contemporary painting. While furnishing an unbiased picture of current Russian art and reproducing paintings shown at various exhibitions (including even those mounted by the Itinerants and the Academy) they devoted as much column space as possible to the latest trends in Western European art. Indeed, never before had the Russian public been offered so broad a survey of contemporary tendencies in German, British, Scandinavian, and progressive nineteenth-century French art, ranging from Ingres, Corot, and Daumier to the Impressionists, Cezanne, Van Gogh, and the then-young Matisse. However, the emphasis was not on these great innovators, whose work paved the way for the evolution of twentieth-century world art, not even on the French Impressionists, whom the journal’s theorists were long inclined to underestimate, but on German and some British and Scandinavian exponents of Art Nouveau.

During its initial period, the journal highly extolled such Symbolists and stylizers as Arnold Bocklin, Max Klinger, Aubrey Beardsley, and Edvard Munch. True, this infatuation with the style moderne, as Art Nouveau was called in Russia, contained much that was casual and extraneous, perhaps even an element of the youthful craving to shock. With the passage of time, however, this gave way to other, more serious interests that were more organically linked with the needs of Russian culture. Indeed, the theme of Russian antiquity gained increasing significance, with the journal evolving from the style moderne to retrospectivism, in the process of which a range of important historical and artistic discoveries were made.

It was the Golovin that provided the basis for a systematic study of the already half-forgotten, if not misconstrued, art and culture of eighteenth-century Russia. Diaghilev, Benois, Grabar and other critics resurrected the names of the painters Dmitry Levitsky and Vladimir Borovikovsky, as well as the splendid Russian Baroque and classical architects. They, too, were the first to explore the heritage of the Russian Romantics and Sentimentalists, to analyze and reassess the work of Orest Kiprensky, Alexei Venetsianov, and Fiodor Tolstoy. The same critics are to be credited for having demolished the established misconceptions regarding early St. Petersburg architecture, completely re-evaluating its artistic significance.The articles contributed by Benois, who adored the beauty of old St. Petersburg, came as a genuine revelation to the journal’s readers. Profound studies devoted to the history of culture markedly influenced the subject matter and creative methods of the Golovin movement.

The editorial staff of the journal also rendered a crucial service to Russian culture by drawing attention to those fields of creative endeavor, which the preceding generation of artists had ignored. Russian book illustration and stage design were revived and innovated. All possible support was given to the decorative applied arts and to the artistic crafts. Finally, a new chapter was opened in Russian art criticism. Research into the past centuries disciplined the new generation of art historians, enabling them to better comprehend the specific aspects of various creative issues and evolve their own methodology.

Such was the fruit of the six-year life of Sergei Diaghilev’s journal. Its organizational achievements gave Russian artists the incentive to go on and form new exhibitional groups and creative associations.

First to show the way were the Moscow participants of the Golovin exhibitions. As early as 1900, they called for limits to Diaghilev’s “dictatorial” powers and by the following year were mounting their own exhibitions, styling themselves the “36.” Toward the close of 1903, they established the Union of Russian Artists that incorporated both the 36 and the Golovin. Its emergence coincided with a period of trial and confusion within the Golovin ranks, whose leaders were becoming increasingly convinced that it could no longer play a progressive role. “It dawned upon us that we had said everything we wanted to say that we were beginning to repeat ourselves, that what we had given would suffice Russian society for a long time to come,” Benois recalled later. Moreover, the contradictions between the literature and art divisions had grown more acute, while an unpleasant disagreement with Princess Maria Tenisheva, who subsidized the journal, also hastened its end. After the last issue had been produced in December 1904, the Golovin group discontinued activities, and its members joined the Union of Russian Artists.

Yet, as Golovin members themselves rightly observed, their journal “achieved what its founders, one might say, never anticipated”. They were able to state with pleasure that “not a single one of their initiatives had petered out... and that all that was being done in a serious and talented manner in art of late was in one way or another related to The Golovin”.

To some extent the Golovin cause was taken up by the Moscow journals Vesy [The Balance] and Zolotoye runo [The Golden Fleece] and the St. Petersburg magazines Stariye gody [Bygone Years] and Apollon [Apollo], Nor did Diaghilev end his organizational activities. In 1905, for instance, with the assistance of the former Golovin members, he mounted a spectacular exhibition of Russian portraits, which contemporaries rightly regarded as an “event of epoch-making significance”, for it “opened a new era in the study of Russian and European art of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth”. A year later, Diaghilev organized, in typical “dictatorial” manner, his last exhibition in Russia, the Seventh Golovin Show, in which he presented, besides the works of the St. Petersburg group, paintings and drawings by Mikhail Vrubel, Konstantin Korovin, Mikhail Larionov, the two gifted young Moscow artists, Nikolai Sapunov and Pavel Kuznetsov, and, posthumously, Victor Borisov-Musatov. After that, he launched his unusually vigorous and persistent campaign to achieve his cherished dream of “exalting Russian artists in the eyes of the West”.

The opening salvo of Russian art’s triumphal progress through Western Europe was delivered by means of a retrospective exhibition ranging from old icons to Golovin paintings, which opened in the Paris Salon d’Automne of 1906.

It was organized according to Alexander Benois’ historical concepts and placed its emphasis on two pinnacles of Russian art, namely, the work of the great portrait painters of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the new painting as represented by Vrubel, Konstantin Korovin, Serov, Borisov-Musatov, Somov, Benois, Bakst, Dobuzhinsky, and Lanceray. In his foreword to the exhibition catalog, Diaghilev emphasized that the show was intended not to embrace every individual chapter of Russian art history but to give an overview of Russian painting from the contemporary angle. “It is a faithful view of the artistic Russia of the present day with its sincere attraction, its respectful faith admiration for the past and its ardent in the future.”

The success of the exhibition exceeded all expectations. This was the first time that the Western European public could admire a truly ordered survey of selected periods in the development of Russian painting and the singular character of contemporary artists.