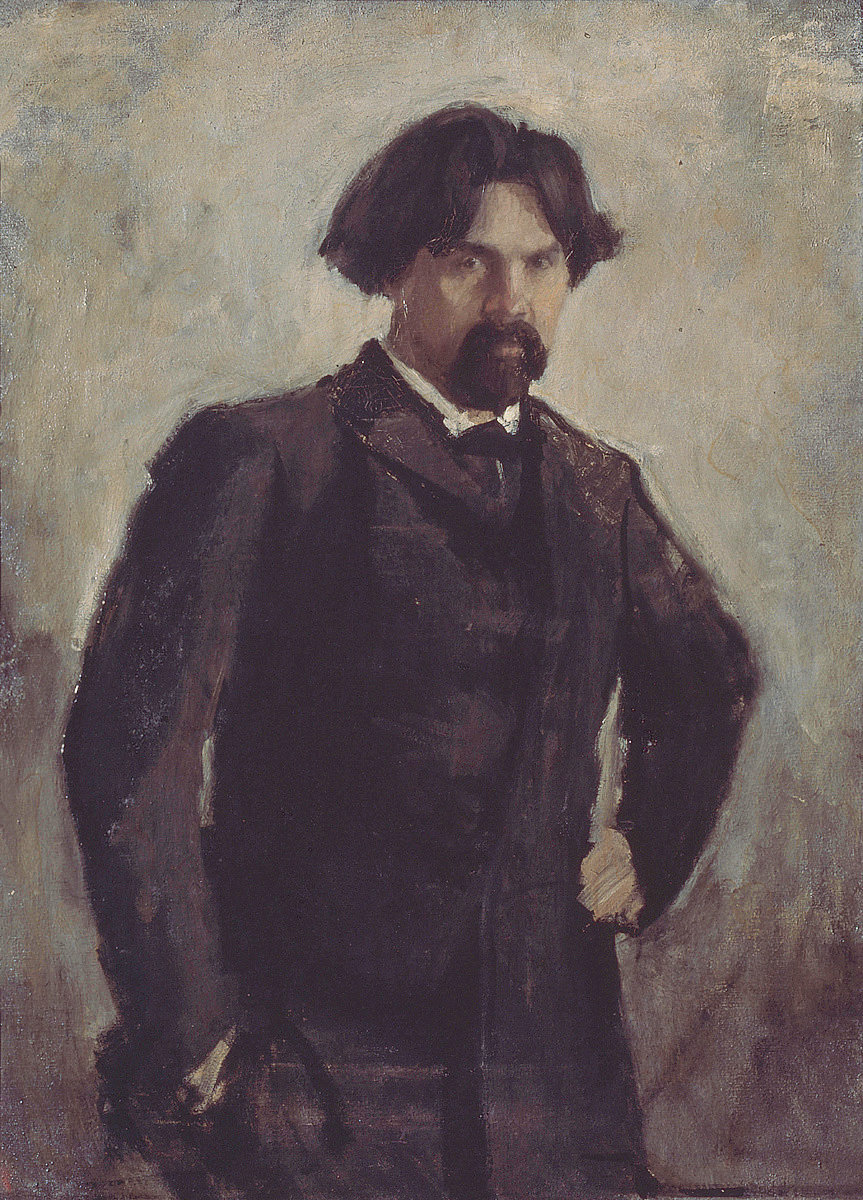

Portrait of the artist Vasily Surikov, 1885. Oil on canvas, 32.9 x 38.1 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

VASILY SURIKOV HIS LIFE AND WORK

The work of Vasily Surikov manifests an amazing fidelity of purpose. The artist put all his heart and soul into reflecting the history of his native Russia, resurrecting the distant past with brilliant veracity. He left only seven large historical paintings, each of which took several years to paint. All are outstanding for their vivid representation of Russian types and characters, underlying national flavour, authentic period atmosphere and profound understanding of the meaning and spirit of the events portrayed. As superlative achievements of realistic historical painting, they comprise a magnificent Russian contribution to world art.

Surikov’s talent as a historical painter revealed itself most powerfully in the 1880s and 1890s, the flowering period of the realist school in Russian art. Firmly linked with the progressive, democratically-minded people of his time, especially the group of painters who were known as the Itinerants (The Society for Circulating Art Exhibitions), he was conspicuous even in that heyday of Russian artistic talent for the astonishing originality of his creative thinking, for his work that is filled with the very breath of history.

The painter’s unusual background quite strongly influenced the development of his talent. He seemed ordained from childhood, spent in a remote Siberian town, to tackle tasks of great creative character.

Vasily Surikov was born on 24 January (12 January, Old Style) 1848, in Krasnoyarsk, into an old Cossack family. His Cossack forefathers from the Don had in the sixteenth century followed Yermak on his “conquest of Siberia”. Though the status and functions of the Siberian Cossacks had markedly changed by the time he was born, the painter was proud of his ancestry, retaining to his dying day fond notions about the old sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Cossacks: their typical forthright, independent and liberty-loving spirit, their patriotism in the defence of Russia from external foes, their elective system of self-government and so on. Indeed, he cherished the Cossack traits of courage, heroism and love of freedom as “family heirlooms”.

Siberia, Surikov’s boyhood home, left a store of impressions that were later to become the taproot of his inspiration. It was with such a background that Surikov came to St Petersburg to study at the Academy of Arts. The contrast was staggering. Life in the capital of European Russia had nothing in common with faraway Siberia. Surikov recorded his impressions in his first painting, dating from 1870, Monument to Peter the Great on Senate Square in St Petersburg. In his drawings for the Polytechnical Exhibition, he already evinced an interest in the activities of people living in the Petrine era (Peter the Great Dragging Sailing Vessels from Onega Bay and Peter and Menshikov with Dutch Sailors). At the Academy, Surikov drew the typical nudes and painted pictures of abstract biblical subjects as required by the syllabus. Having assimilated all that the Academy had to offer, Surikov retained intact in his work boyhood reminiscences and vivid mental images of Siberia. The artisanship has not marred his individual talent; on the contrary, it developed an independent attitude, one of firmly rejecting formal academic ostentation in historical painting.

Surikov himself said that at the Academy he developed an interest in three periods of ancient history. “At first, remote antiquity, mostly Egypt, then Rome with its empire that encompassed half the world, and, finally, the Christian world that arose on its ruins.” Products of those years were his sketches for Cleopatra (1874) after Pushkin’s story Egyptian Nights, Belshazzar’s Feast (1874), The Assassination of Julius Caesar (1870s) and The Apostle Paul Defending the Dogma of the Christian Faith Before King Agrippa, His Sister Berenice and Proconsul Festus (1875).

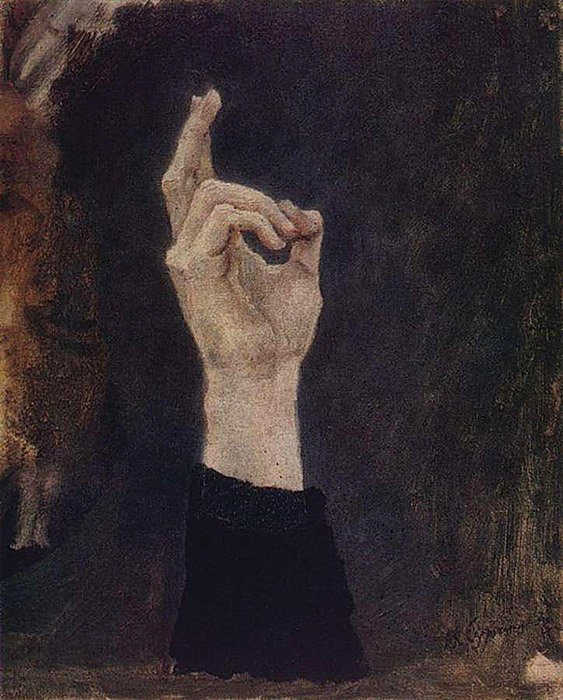

Belshazzar’s Feast depicts the prophet Daniel interpreting the early demise implied by the fiery writing on the wall to the sinful Babylonian king. In composition, modelling and presentation the work is still typically academic, though it already manifests its creator’s temperament. King Belshazzar cosseted in luxury is contrasted to the prophet Daniel, whose uplifted hand points to the stern warning.

Making skilful use of the phosphoric brilliance of the writing on the wall, Surikov boldly modelled figures and objects. The half-naked bodies with arms and hands thrust out in an expression of despair seem marble-like in the stream of bluish light. The artist received the first prize for the painting. Printed reproductions of it drew the public eye to the young painter.

At the same time, Surikov produced his Princely Court (1874). This is the first picture by him on a Russian historical theme to have come down to the present day. (The earliest composition, The Murder of Dmitry the Impostor, from 1870, has not survived.) The young artist may not have achieved a uniform measure of success in all parts of the work, but it is clear from this early effort that his creative approach did not conform to that ordained by the Academy for assignments on mythological or biblical themes. The theme set this time by the professors of the Academy was “the clash of Christianity and paganism in the time of Prince Vladimir.” It caught Surikov’s imagination and he decided to depict a moment soon after the adoption of Christianity when the Eastern Slavs still retained many heathen features in appearance and behaviour.

Depicted in the canvas is a courtyard with a prince’s palatial residence. Sitting in state on the porch under a canopy of gonfalons and surrounded by clergy is an elderly prince. He is dressed in the ancient Russian style — an embroidered scarlet cloak, a fur-trimmed hat and red boots. In a gallery on the right, a seat of honour has been set up for the princess, too. She wears a crown studded with semi-precious stones and strings of pearls at the temples (like those of Byzantine empresses), and she is dressed in a resplendent brocade gown. Next to the prince, judging from his staff, mantle, and cowl, is the bishop appointed to Kievan Russia from Byzantium.

The yard in front of the porch is packed with people — a trial is taking place. In the centre of the left-hand group is a woman with her children: she is on her knees petitioning the prince. On the right is the respondent — the highly colourful figure of a Slav warrior of pre-Christian Russia. In front of him, as if shielding her man from the prince’s wrath, another woman stands silently, also with her children and claiming her rights. It is not difficult to guess what the case is about: after the adoption of Christianity in Russia the church began to enforce monogamy and persecute “those who without shame and fear possess two wives” and those who kept concubines in addition to a wife. These recent pagans could not bring themselves to regard as criminal something that for ages had been accepted as normal, with their own prince, moreover, setting a blatant example but nevertheless passing judgement on them for doing the very same thing... And the semi-wild barbarian, one of those who bravely battle Russia’s enemies, cannot understand what he is being accused of.

The positive features that were later to be developed in Surikov’s work are more evident in The Princely Court than in Belshazzar’s Feast. These include the artist’s deep interest in the life and typological aspects of the common people of ancient Russia, here demonstratively placed in the foreground.

However, neither Belshazzar’s Feast nor The Princely Court were truly finished paintings — being rather like sketches.

Having obtained all the qualifying awards and medals during his studies at the Academy, Surikov was allowed to compete for the Grand Gold Medal on the theme of The Apostle Paul Defending the Dogma of the Christian Faith Before King Agrippa, His Sister Berenice and Proconsul Festus.

The subject presented quite a challenge, for it lacked both action and drama. However, by his imaginative approach, Surikov imparted the breath of life to this rather abstract theme. The collision between the three religions, Christianity, Judaism and Roman paganism, is personified through Paul, Agrippa and Festus.

The painter tried to individualize all three, and although unable to cope fully with the unrewarding task, created some images, especially the spiritually strong Paul, which attest to his great talent and fine Academy-honed craftsmanship.

The more progressive Academy professors insisted that Surikov be awarded the Gold Medal and the associated three-year tour abroad on an Academy stipendium. However, the conservative-minded group won and Surikov did not get the prize. He then decided to accept a remunerative commission for four murals on Ecumenical Council history for the huge Cathedral of Christ the Saviour then being built in Moscow, hoping his fee would afford him several years of independence.

The Apostle Paul Defending the Dogma of the Christian Faith Before King Agrippa, His Sister Berenice and Proconsul Festus, 1875. Oil on canvas, 142 x 218.5 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Surikov’s move to Moscow opened a new chapter in his life. He was fascinated by the old buildings and churches, Red Square, and the Kremlin.

“An odd sensation came over me here in Moscow,” Surikov recollected later. “First, I felt much more at home than in St Petersburg. Moscow had something far more reminiscent of Krasnoyarsk about it, especially in winter.

One could walk in a street in the twilight, turn a corner, and suddenly come face to face with something familiar, just like in Siberia. Like forgotten dreams, more and more scenes of my boyhood and youth returned to me. I recalled the types and the costumes and nostalgically yearned for all this, as a heartfelt and priceless treasure.” His walks along the Kremlin wall, at an hour, when gathering darkness softened silhouettes, caused him to conjure up in his mind’s eye blurred yet enchanting pictures. At one point he imagined by the wall “people standing dressed in old Russian style, at another one fancied that this very moment woman wearing brocaded quilted jackets and traditional kika headdresses would step out from behind the tower. It seemed so clear that I even paused in expectation. Soon I caught myself filling the space at the foot of these walls with familiar types and costumes, of the kind seen so often back home”.

For Surikov as a painter of historical canvases, this was the beginning of a true artistic vision. “Here by the Lobnoye Mesto and St Basil’s on Red Square,” Surikov wrote, “there suddenly erupted in my mind’s eye the scene of the execution of the Streltsy, so distinctly that my heart began to beat faster.” “When I stepped onto Red Square,” Surikov said of his painting The Morning of the Execution of the Streltsy, “it evoked memories of Siberia, and out of those memories emerged all the faces for the Streltsy, and the colour scheme and composition, too...”

“The picture demanded long and laborious toil,” Surikov’s biographer records the artist’s words, “and though many studies were painted here in Moscow, in the central images of the condemned... and the figures of the weeping women, Surikov for the first time recorded the features of people he had known well in Krasnoyarsk.”

All this serves to explain the role of Siberia, and his childhood and youthful impressions in the shaping of Surikov’s talent. But however, close the links that bind the artist’s biography to his creative endeavour, they alone can explain neither its chief thematic interest nor the artist’s individual style. These were all determined by the social conditions and the concrete historical environment in which Surikov’s art developed.

Surikov’s talents blossomed between the late 1870s and 1900s. The best works of Russian art produced at that time developed a deeper understanding of the age of Peter the Great, an approach equally free of official embellishment and subjectivist moralizing. Interesting in this context are the comments on the Streltsy made by Surikov’s biographer, which the artist read and approved without changing a word: “The picture turned out powerful, frightening and, above all, truly historical. Looking at it you actually feel how harrowing the situation is for all concerned. You feel an agonizing pity for these hundreds of people condemned to death, but you understand Peter too, as he sits there with clenched teeth, gripping the reins in his list, and boldly examines the faces of the men he considers sworn enemies of his great cause. As in history itself, you can side with either party, depending on your sympathies and antipathies, but you know that finally, nobody is right in history and nobody wrong, there is only the horror of collisions such as this, that are never resolved but with the shedding of a sea of blood.”

In Surikov’s works of the 1880s, the Russian people is shown in conflict with itself, at moments of tragedy, when the full force of a human character is often revealed — such as the Execution of the Streltsy, the Incarceration of Morozova or the Exiling of Menshikov. This was an aspect of history suggested by the contemporary revolutionary atmosphere in Russia following the inconclusive reforms of the 1860s, the abolition of serfdom and the dashing of the hopes it raised. Yermcik’s Conquest of Siberia and Suvorov Crossing the Alps, two pictures that Surikov painted in the 1890s, present a different set of issues and a different aspect of Russian history. Here the people comprise one integral force; their history-making efforts are not marred by any tragic internal schism, any discernible conflict with tsarist autocracy. The portrayal of the heroism of the common people became the artist’s supreme aim.

In the 1900s, when a wave of strikes and demonstrations swept Russia and the 1905 revolution was brewing, Surikov displayed a deep interest in the popular uprisings of earlier centuries. The artist worked on the composition of The Krasnoyarsk Revolt of 1695-98 and painted his large Stepan Razin which he exhibited in Moscow in December 1906. In 1908 he began his A Princess Visiting a Convent, a piece inspired by profound reflections on a woman’s lot in mediaeval Russia, which he completed between 1910 and 1912. In the first decade of the new century, Surikov painted a considerable number of portraits and landscapes, as well as watercolours. He tackled various subjects, but his work seemed to have lost its previous integrity and at times indicated vacillation. Between 1909 and 1910 Surikov returned to Razin. In 1915, he produced several stinging anticlerical cartoons, and also exhibited his unsuccessful Annunciation.

The concepts born in the artist’s final years were not destined for completion; nevertheless, surviving sketches and studies attest to their importance. Surikov had always been fascinated by the eighteenth-century Pugachov rebellion and in 1909, after Razin, he produced an extremely well-characterized and superbly coloured study in oils for the peasant leader. His continued interest in the subject is shown by an excellent 1911 drawing of Pugachov, which can be seen at the Tretyakov Gallery. Curiously enough, he drew it while painting A Princess Visiting a Convent in Rostov — which makes a remarkable contrast between a purely voluntary incarceration before a slow wasting away behind the walls of a convent, and the forcible caging of Pugachov prior to his execution. Still, as the sketch demonstrates, the peasant leader’s indomitable spirit has not been crushed. His eyes reveal more than simply the bitterness of defeat; they also display human dignity and iron will.

Princess Olga Meeting Igor’s Corpse, 1915. Watercolour on paper, 36 x 61.5 cm. The Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

In that same year of 1909 the artist conceived his Princess Olga Meeting Igor’s Corpse — which, incidentally, he decided to paint, like Morozova and A Princess Visiting a Convent, after reading Ivan Zabelin’s book examining the lot and role of the Russian woman in mediaeval Russia at various stages of its history.

Zabelin maintained that the Russian woman of pagan times, and Olga in particular, was a socially active figure. According to Zabelin, Princess Olga embodied the heroic period in the life of Russian womanhood, an idea to which Surikov had given much thought while producing his gallery of female portraits. This was the first time after dealing with the much closer period of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, that he decided to tackle pre-Christian tenth-century Russia. In search of background material and new impressions, the artist, in full accord with his established principles, again turned to Siberia, which he saw as a treasure house of Russian history. To make studies he set off for the Minusinsk steppe lands and the shores of Lake Shira, where traces and relics of hoary antiquity still existed, such as barrows, stone idols, and — still very much alive — nomad tents and folk bards. Sketches depict the steppe with hills on the horizon, a sloping riverbank and throngs of people. The raft carrying the mortal remains of Prince Igor draws up to the bank. Amid the array of mourners and warriors is Princess Olga herself. Her arm is uplifted as she vows to wreak vengeance on the Drevlians for the death of her husband. Head downcast, her young son Sviatoslav clings to his mother.

The first sketch for this picture was made in 1909, the eleventh and last in 1915. Death intervened at a moment when the artist had already found a solution to the composition of the future painting. The sketches themselves are quite adequate to provide a good notion of the rare beauty this picture would have become.

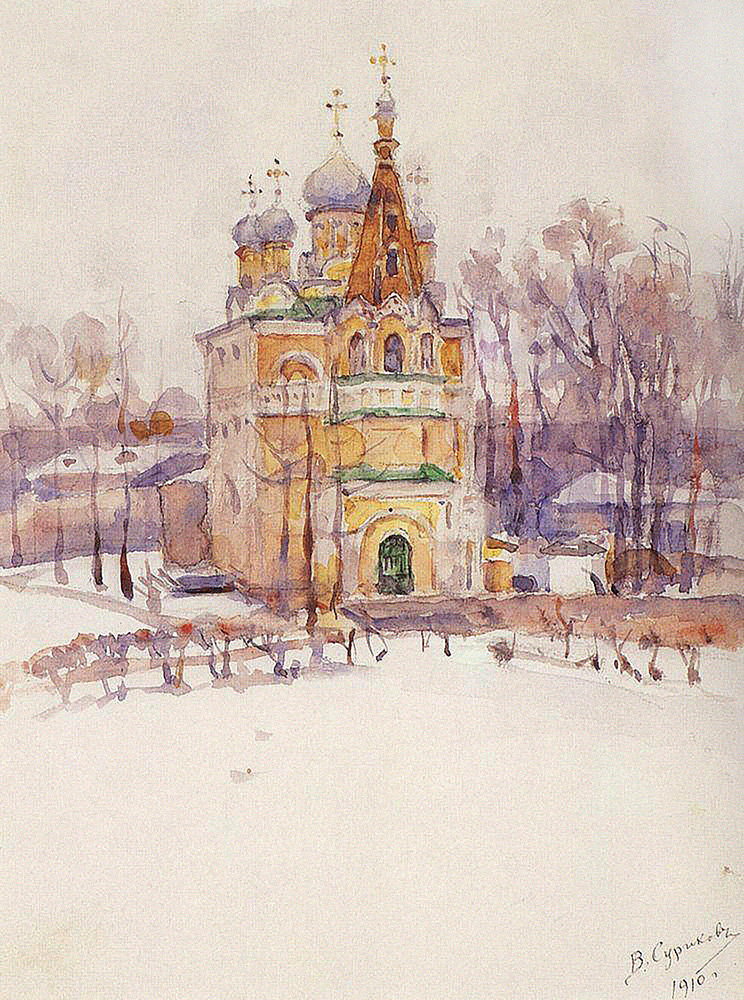

Little heed has yet been paid to another aspect of Surikov’s output — his watercolours, yet he undoubtedly rendered a great service by reviving — in the late nineteenth century, a time when artists were using watercolours merely as an auxiliary medium — the method as an important sphere of artistic endeavour in its own right, with its own specific techniques and merits different from oils. Such works as Roses in a Goblet (1874) and Samovar (1876) are among his best watercolours.

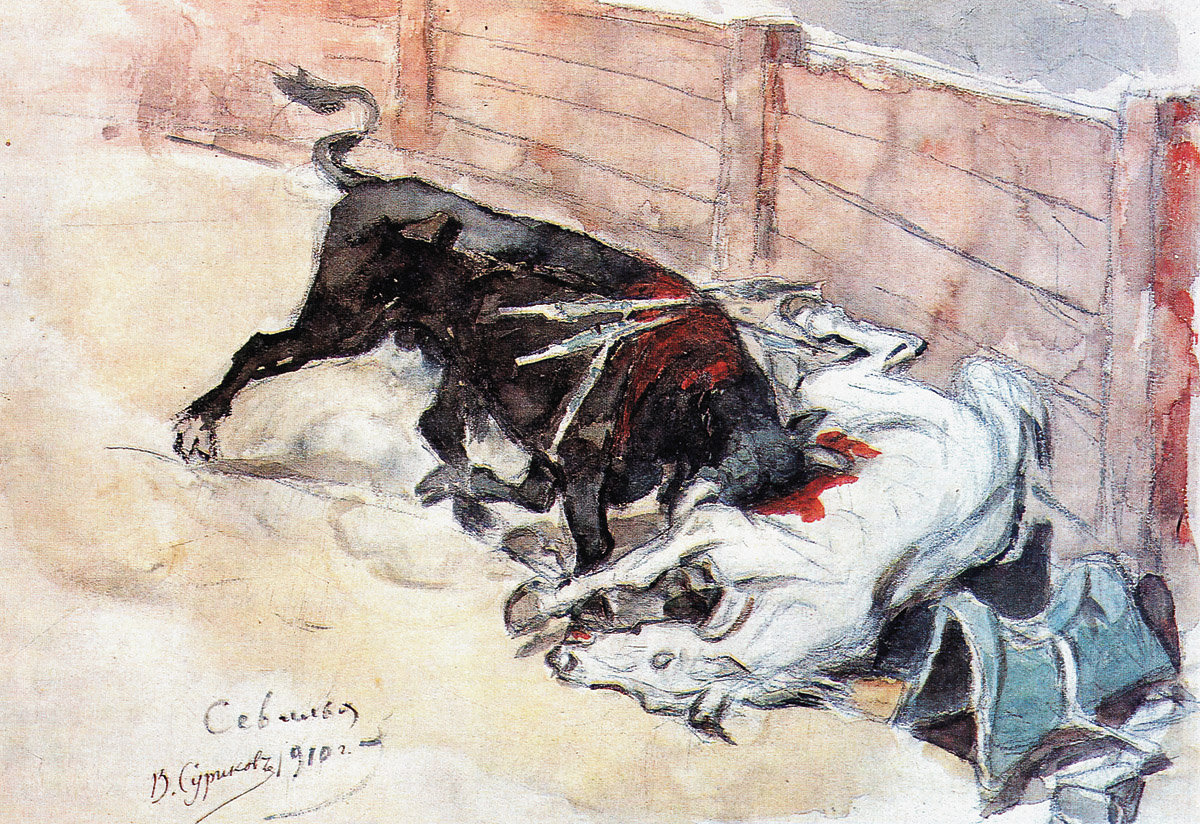

Surikov developed a perfect mastery of watercolour technique, using the brush quickly, accurately and broadly, with no superfluous strokes. His colour is extremely pure, the tinting refined. In landscapes, he dealt very successfully with lighting and aerial perspective as is shown by his Krasnoyarsk and Minusinsk pieces of the 1870s. While engaged on Menshikov, to achieve greater vibrancy and purity of colour, Surikov again applied himself to the watercolour (An Icon Corner in a Peasant House, done in 1883; a study of his wife for Maria Menshikova, and of Sophia Kropotkina with a guitar, done in 1882). He worked particularly productively in this technique during his first trip abroad in 1884 before starting Morozova. In Italy, the artist reached his watercolour peak in such compositions as St Peter’s in Rome, Venice and Pompeii, which are all enchanting for their harmonious colour directly and warmly captured from life. These works undoubtedly possess artistic merit in their own right. Surikov’s watercolours produced in Spain in 1910 brilliantly convey the country’s bright sunshine, vibrant, resonant colours and distinctive architecture, whether Andalusia with its contrasting white walls and red-tiled rooftops against a backdrop of olive green; the sun-drenched courtyard of the Alhambra in Granada; lush green palm trees against Valencia’s intensely blue sky; the sun-scorched cliffs of Toledo with their honey-hued fortress towers or the dynamic, exciting bullfights of Seville and Barcelona. Striking colour contrasts in bright sunshine combine in these freely and broadly executed works with a masterly treatment of space, air and volume — features that can also be seen in the Crimean landscapes painted in the last years of the artist’s life.

In 1915 Surikov spent the summer in Alupka on the Black Sea coast of the Crimea. This long exposure to the blazing sun proved disastrous. In autumn he came down with a severe heart ailment which tormented him all throughout the winter up to his death on 6 March 1916. His last words were: “I am disappearing.”

Surikov’s greatness is that, while not modernizing history, he profoundly sensed in the flow of life the inner bond between present and past, which he realized would continue unbroken into the future as well. He understood that contemporary life, society, human characters, culture, customs, and aspirations were rooted in the centuries and at the same time paved the way for the future. In figures of the past, Surikov was able to detect features that were especially important to keep alive in contemporary memory.

Surikov’s work is a fine example of the progressive art of his period, art championing realism, genuine patriotism and democratic principles. His monumental canvases are permeated with national pride and affection for the Russian people, for their love of liberty, courage, valour, creative powers, and the fine aesthetic taste so clearly evident in the traditional arts and handicrafts. Why did the painter seek subject matter in his nation’s glorious past? Because he was one with his people in their life and struggle because he had every belief in their great future.

Venice. The Doges’ Palace, 1900. Watercolour on paper, 22.6 x 30 cm. Collection of the artist’s family, Moscow.

Roman Carnival, 1884. Sketch of the composition. Watercolour and lead pencil on paper, 21 x 27 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Bullfight in Seville, 1910. Watercolour and lead pencil on paper, 25.5 x 34.7 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

HISTORICAL PAINTINGS

SURIKOV’S GREATNESS IS THAT,

WHILE NOT MODERNIZING HISTORY,

HE PROFOUNDLY SENSED IN THE FLOW

OF LIFE THE INNER BOND

BETWEEN PRESENT AND PAST,

WHICH HE REALIZED

WOULD CONTINUE UNBROKEN

INTO THE FUTURE AS WELL.

HE UNDERSTOOD THAT CONTEMPORARY LIFE,

SOCIETY, HUMAN CHARACTERS, CULTURE,

MORES AND ASPIRATIONS

WERE ROOTED IN THE CENTURIES

AND AT THE SAME TIME PAVED THE WAY

FOR THE FUTURE.