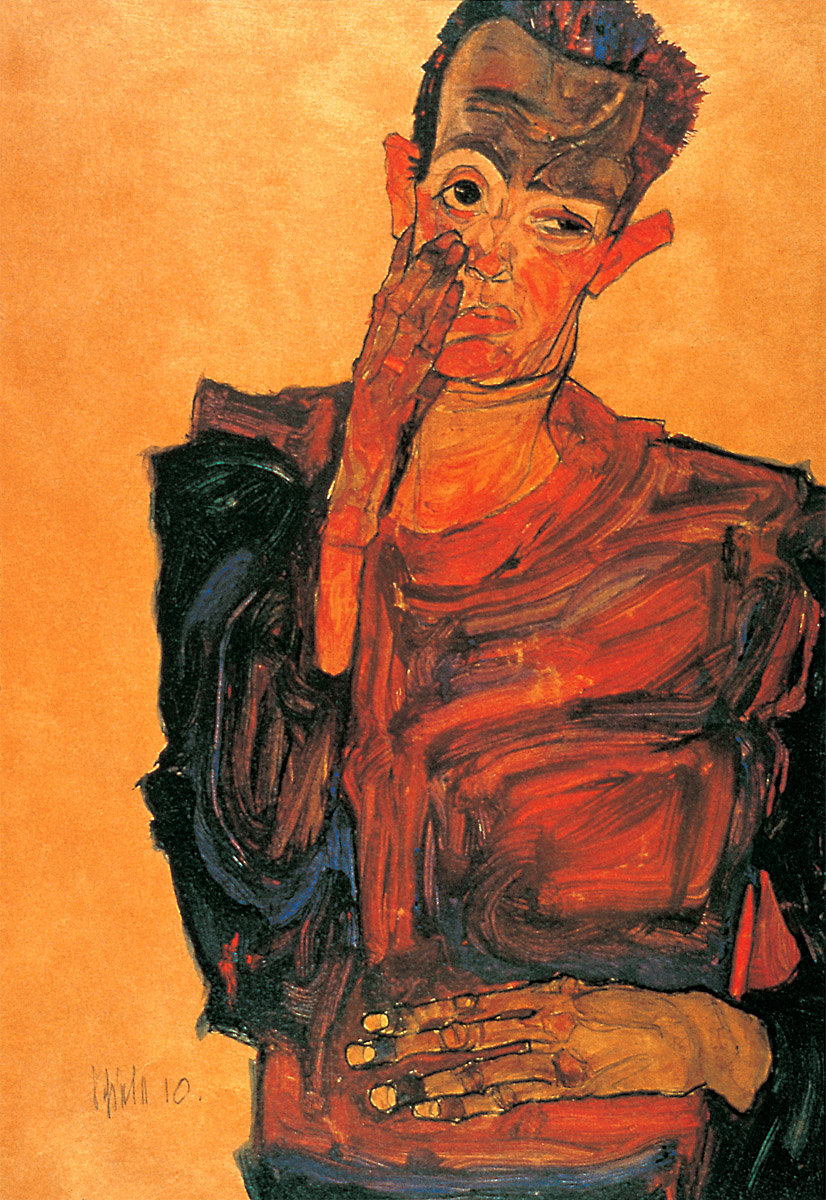

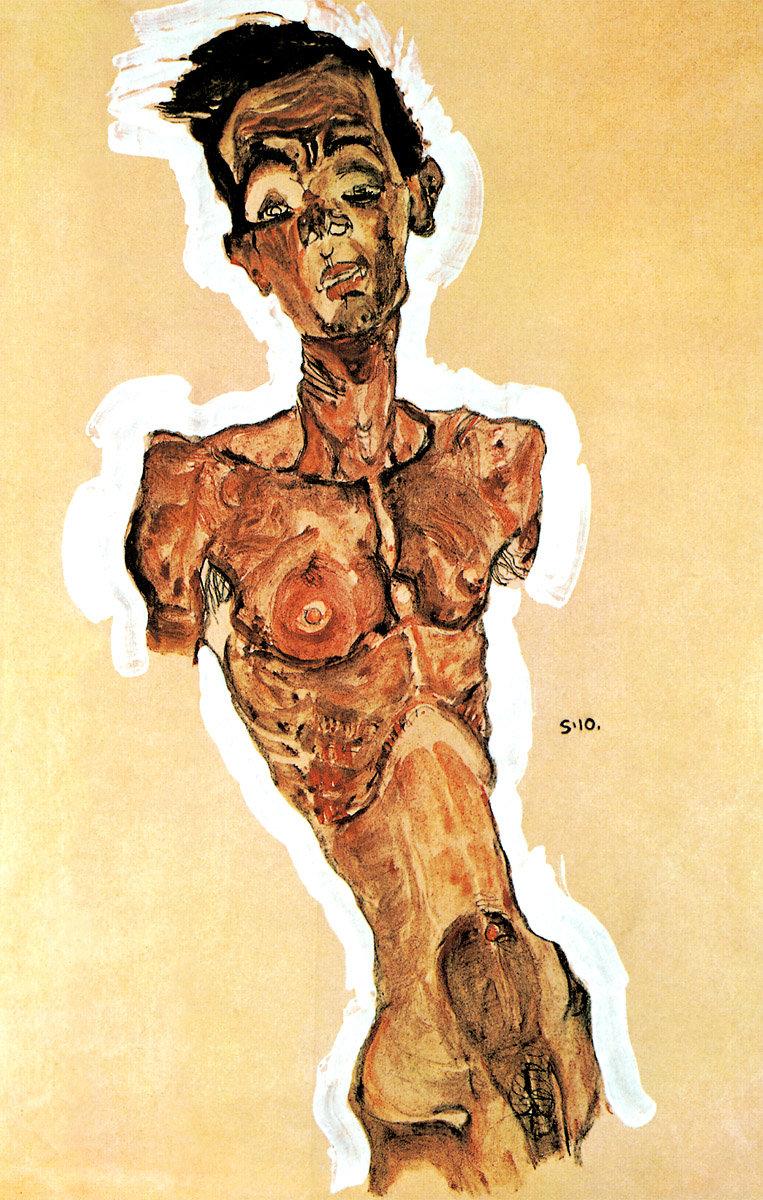

Self-portrait Pulling Cheek, 1910. Gouache, watercolour and pencil, 44.3 x 30.5 cm. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

HIS LIFE

In 1964, Oskar Kokoschka evaluated the first great Schiele Exhibition in London as “pornographic”. In the age of discovery of modern art and loss of “subject”, Schiele responded that for him there existed no modernity, only the “eternal”. Schiele’s world shrank into portraits of the body, locally and temporally non-committal. Self-discovery is expressed in an unrelenting revelation of himself as well as of his models. The German art encyclopedia, compiled by Thieme and Becker, described Schiele as an eroticist because Schiele’s art is an erotic portrayal of the human body. Futhermore, Schiele studied both male and female bodies. His models express an incredible freedom with respect to their own sexuality, self-love, homosexuality or voyeurism, as well as skillfully seducing the viewer.

For Schiele, the clichéd ideas of feminine beauty did not interest him. He knew that the urge to look is interconnected with the mechanisms of disgust and allure. The body contains the power of sex and death within itself. The photograph of Schiele on his deathbed, depicts the twenty-eight year old looking asleep, his gaunt body is completely emaciated, his head resting on his bent arm; the similarity to his drawings is astounding. Because of the danger of infection, his last visitors were able to communicate with the Spanish flu-infected Schiele only by way of a mirror, which was set up on the threshold between his room and the parlour.

During the same year, 1918, Schiele had designed a mausoleum for himself and his wife. Did he know, he who had so often distinguished himself as a person of foresight, of his nearing death? Did his individual fate fuse collectively with the fall of the old system, that of the Habsburg Empire? Schiele’s productive life scarcely extended beyond ten years, yet during this time he produced 334 oil paintings and 2,503 drawings (Jane Kallir, New York. 1990). He painted portraits and still-lifes land and townscapes; however, he became famous for his draftsmanship. While Sigmund Freud exposed the repressed pleasure principles of upper-class Viennese society, which put its women into corsets and bulging gowns and granted them solely a role as future mothers, Schiele bares his models. His nude studies penetrate brutally into the privacy of his models and finally confront the viewer with his or her own sexuality.

Schiele’s Childhood

In modern industrial times, with the noise of racing steam engines and factories and the human masses working in them, Egon Schiele was born in the railway station hall of Tulln, a small, lower Austrian town on the Danube on June 12, 1890. After his older sisters Melanie (1886-1974) and Elvira (1883-1893), he was the third child of the railway director Adolf Eugen (1850-1905) and his wife Marie, née Soukoup (1862-1935). The shadows of three male stillbirths were a precursor for the only boy, who in his third year of life would lose his ten-year-old sister Elvira. The high infant mortality rate was the lot of former times, a fate which Schiele’s later work and his pictures of women would characterize. In 1900, he attended the grammar school in Krems. But he was a poor pupil, who constantly took refuge in his drawings, which his enraged father burned.

In 1902, Schiele’s father sent his son to the regional grammar and upper secondary school in Klosterneuburg. The young Schiele had a difficult childhood marked by his father’s ill health. He suffered from syphilis, which, according to family chronicles, he is said to have contracted while on his honeymoon as a result of a visit to a bordello in Triest. His wife fled from the bedroom during the wedding night and the marriage was only consummated on the fourth day, on which he infected her also. Despair characterized Schiele’s father, who, retired early sat at home dressed in his service uniform in a state of mental confusion. In the summer of 1904, stricken by increasing paralysis, he tried to throw himself out of a window. He finally died after a long period of suffering on New Year’s Day 1905. The father, who during a fit of insanity burned all his railroad stocks, left his wife and children destitute. An uncle, Leopold Czihaczek, chief inspector of the imperial and royal railway, assumed joint custody of the fifteen-year-old Egon, for whom he planned the traditional family role of railroad worker. During this time, young Schiele wore second-hand clothing handed down from his uncle and stiff white collars made from paper. It seems that Schiele had been very close to his father for he, too, had possessed a certain talent for drawing, had collected butterflies and minerals and was drawn to the natural world.

Years later, Schiele wrote to his sister: “I have, in fact, experienced a beautiful spiritual occurrence today, I was awake, yet spellbound by a ghost who presented himself to me in a dream before waking, so long as he spoke with me, I was rigid and speechless.” Unable to accept the death of his father, Schiele let him rise again in visions. He reported that his father had been with him and spoken to him at length. In contrast, distance and misunderstanding characterized his relationship with his mother who, living in dire financial straits, expected her son to support her; in return, the older sister would work for the railroad.

However, Schiele, who had been pampered by women during childhood, claimed to be “an eternal child”. By a stroke of fate, the painter Karl Ludwig Strauch (1875-1959), instructed the gifted youth in draftsmanship; the artist Max Kahrer of Klosterneuburg looked after the boy as well. In 1906, at the age of only sixteen, Schiele passed the entrance examination for the general art class at the Academy of Visual Arts in Vienna on his first attempt. Even the strict uncle, in whose household Schiele now took his midday meals, sent a telegram to Schiele’s mother: “Passed”.

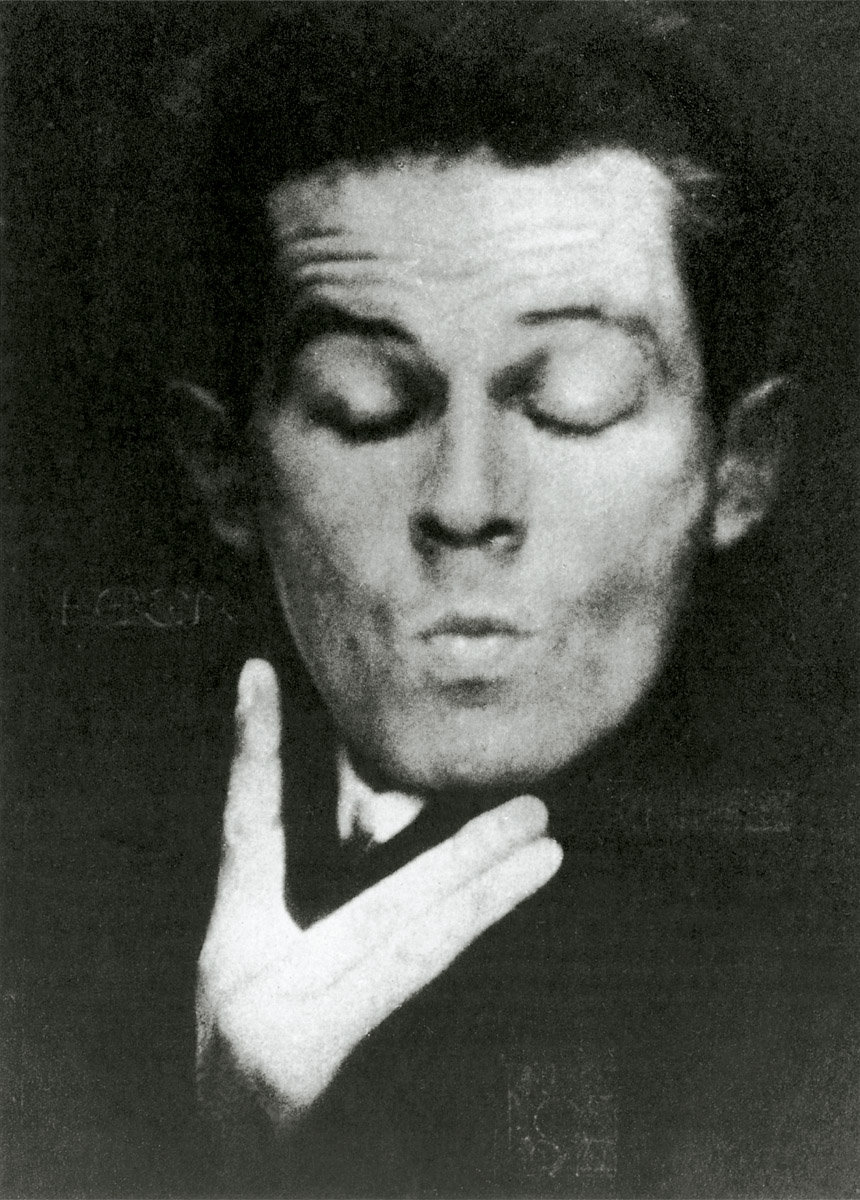

Self-portrait, 1910. Black crayon, watercolour, and gouache, 44.3 x 30.6 cm. Leopold Museum, Vienna.

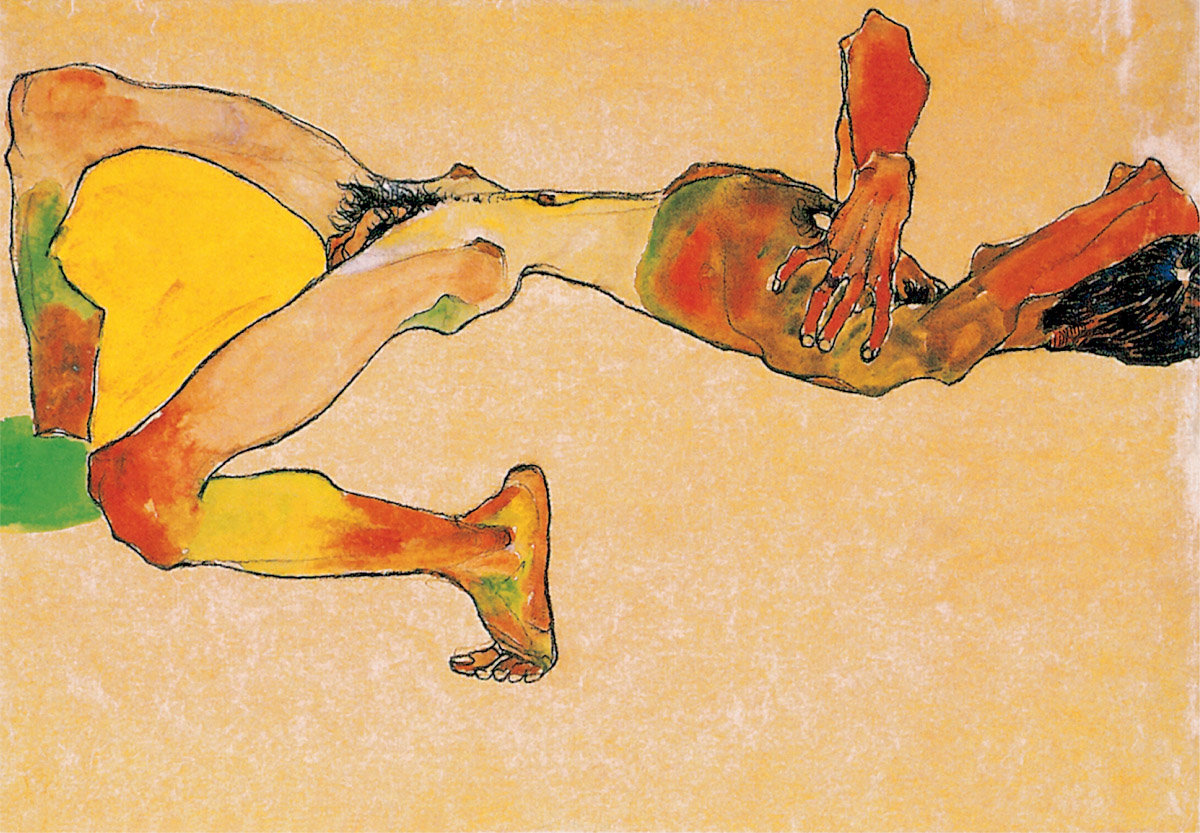

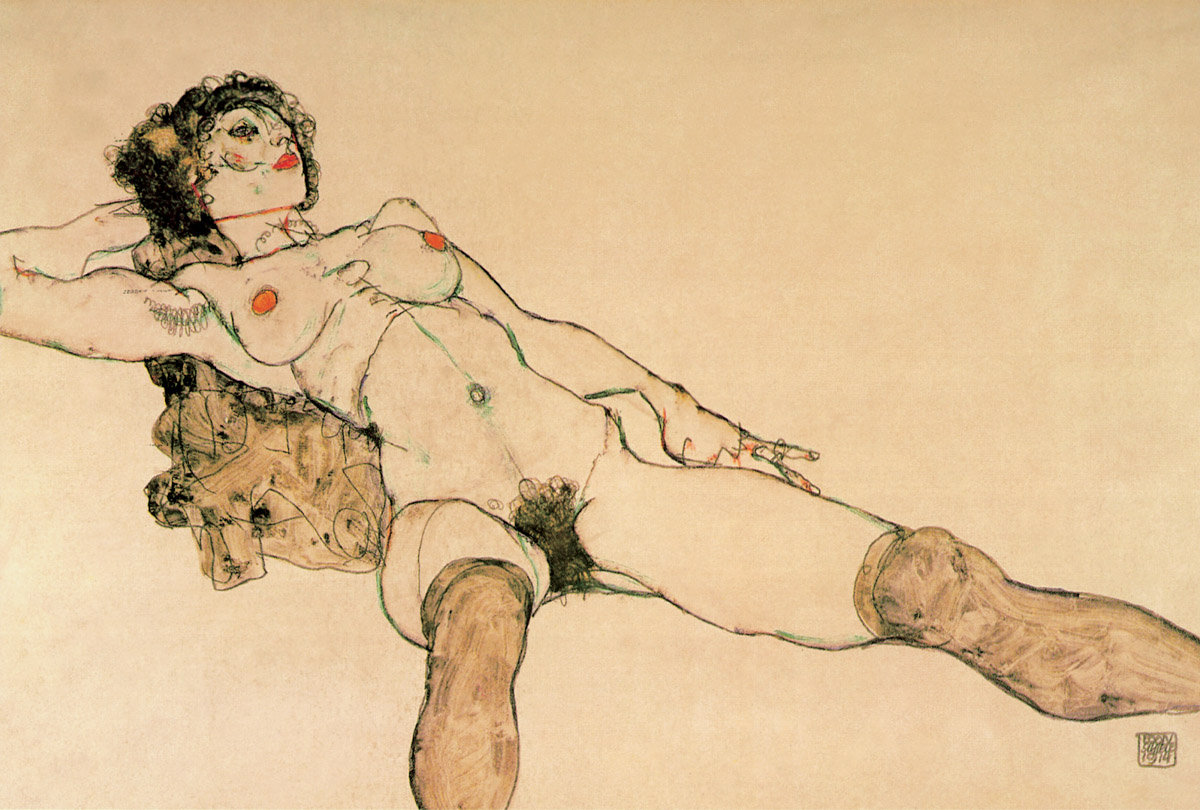

Reclining Nude with Black Stockings, 1911. Watercolour and pencil, 22.9 x 43.5 cm. Private collection.

The Favourite Sister, Gerti

The nude study of the fiery redhead with the small belly, fleshy bosom and tousled pubic hair is his younger sister Gertrude (1894-1981). In another watercolour, Gerti reclines backwards, still fully clothed with black stockings and shoes, and lifts the black hem of her dress from under which the red orifice of her body gapes. Schiele draws no bed, no chair, only the provocative gesture of his sister’s body offering itself. Incestuous fantasies? The sister, four years his junior, was a compliant subject for him.

At the same time as Sigmund Freud discovered that self-discovery occurs by way of erotic experiences, and the urge to look emerges as a spontaneous sexual expression within the child, young Egon recorded confrontations with the opposite sex on paper. He incorporated erotic games of discovery and shows an unabashed interest in the genitalia of his model into his nude studies. The forbidden gaze, searching for the opened female vagina beneath the rustling of the skirt hem and white lace. Gerti with her freckled skin, the green eyes and red hair is the prototype of all the later women and models of Schiele.

Vienna at the Turn of the Century

Vienna was the capital city of the Hapsburg monarchy, a state of multiple ethnicities consisting of twelve nations with a population of approximately thirty million. Emperor Franz Josef maintained strict Spanish court etiquette. Yet, on the government’s fortieth anniversary, he began a large-scale conversion of the city with its approximately 850 public and private monumental structures and buildings. At this time, the influx of the rural population selling itself to the big city was increasing. Simultaneously, increasing industrialization resulted in the emergence of a proletariat in the suburbs, while the newly rich bourgeoisie settled in the exclusive Ring Street. In the writers’ cafés, Leo Trotski, Lenin and later on Hitler consulted periodicals on display and brooded over the beginning century.

Just how musty the artistic climate in Vienna was is evidenced by the scandal over Engelhard’s picture Young Girl under a Cherry Tree, in 1893. The painting was repudiated on the grounds of “respect for the genteel female audience, which one does not wish to embarrass so painfully vis-à-vis such an open-hearted naturalistic study”. What hypocrisy, when official exhibitions of nude studies, the obligation of every artist, had long been an institution. In 1897, Klimt together with his Viennese fellow artists founded the Vienna Secession, a splinter group separate from the officially accepted conduct for artists with the motto: “To the times its art, to the art its freedom”.

In 1898, the first exhibition took place in a building belonging to the horticultural society. It was distinguished from the usual exhibitions which included several thousand works by offering an elite selection of 100 to 200 works of art. The proceeds generated by the attendance of approximately 100,000 visitors financed a new gallery designed by the architect Olbrich. Exhibitions by Rodin, Kollwitz, Hodler, Manet, Monet, Renoir, Cézanne and Van Gogh opened the doors to the most up-to-date international art world. Visual artists worked beside renowned writers and musicians such as Rilke, Schnitzler, Alternberg, Schönberg and Alban Berg for the periodical Ver Sacrum. Here they developed the idea of the complete work of art, which encompassed all artistic areas. Simultaneously, the Secession required the abolition of the distinction between higher and lower art, art for the rich and art for the poor and declared art common property. Yet, this demand of the art nouveau generation remained a privilege of the upper class striving for the ideal that “art is a life style”, which encompassed architectural style, interior design, clothing and jewellery.

Standing Girl in Blue Dress and Green Stockings, Back View, 1913. Watercolour and pencil, 47 x 31 cm. Private collection.

Reclining Male Nude with Yellow Pillow, 1910. Black crayon, watercolour and gouache on paper, 31.1 x 45.4 cm. Private collection.

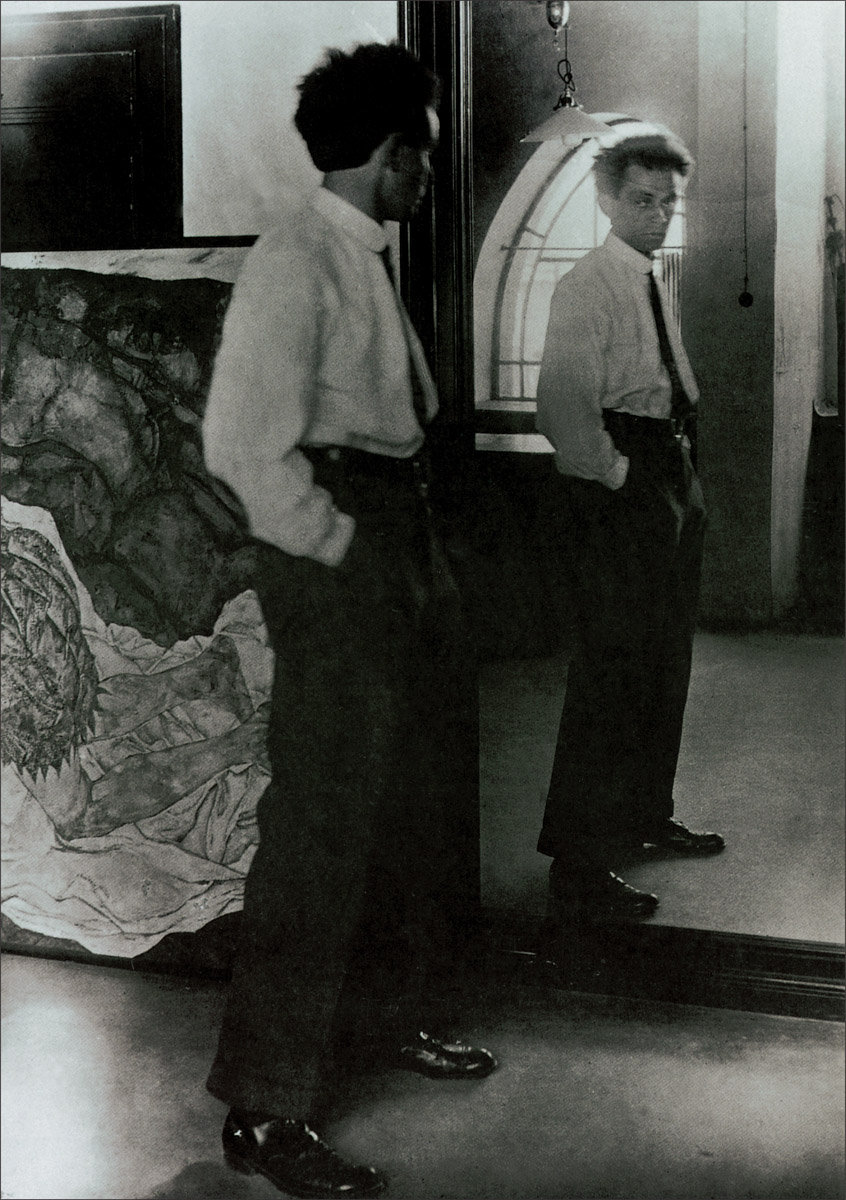

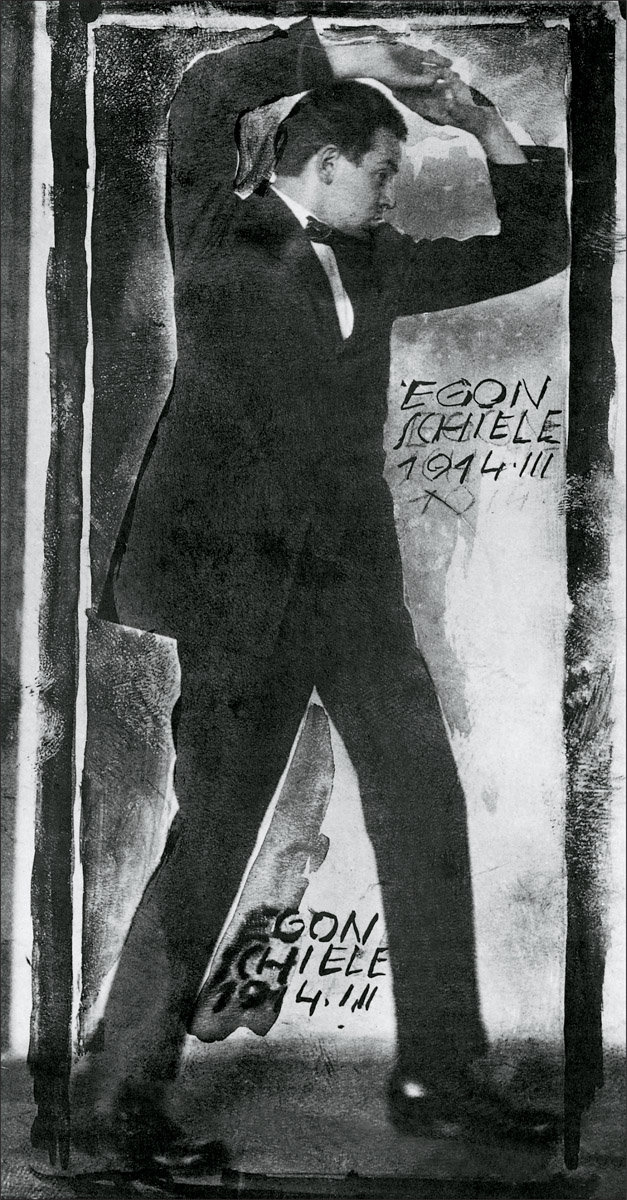

Egon Schiele Standing in front of His Mirror, 1915. Photography. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

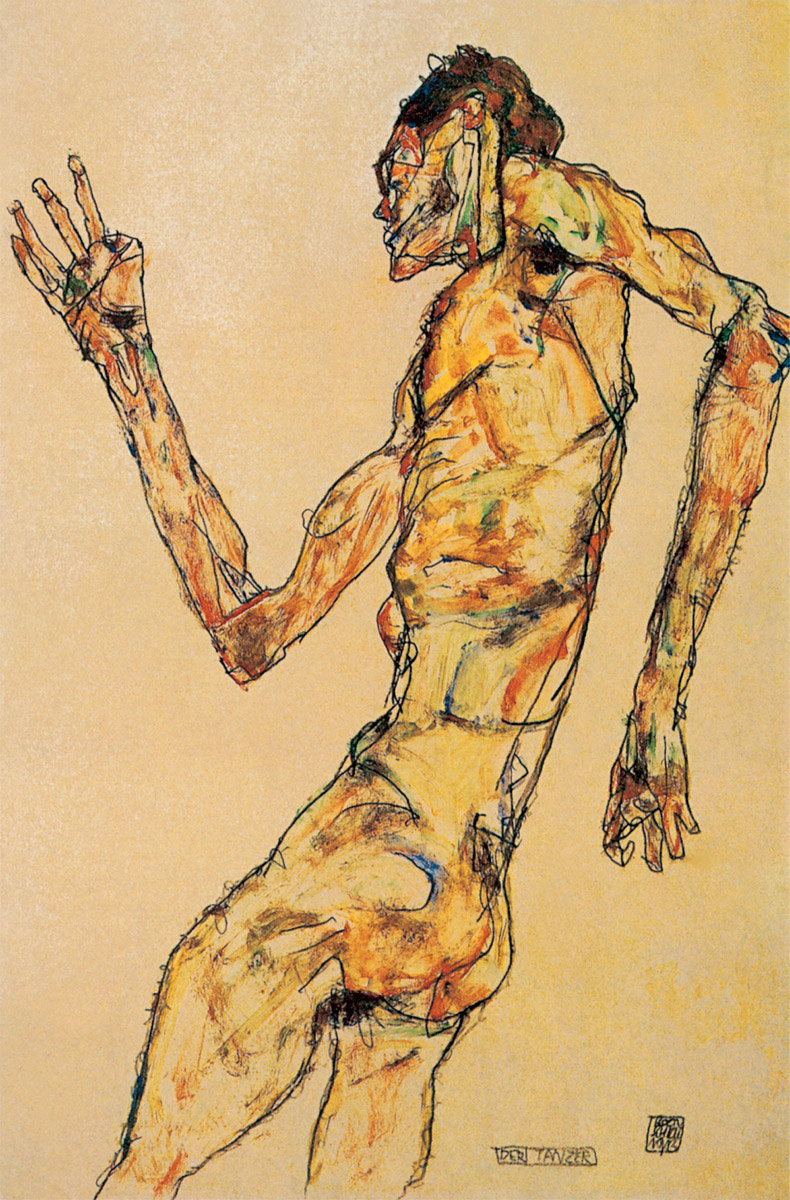

Self-portrait Arms Drawn-Back, 1915. Gouache, pastel and charcoal, 32.9 x 44.8 cm. E.W. Kornfeld collection.

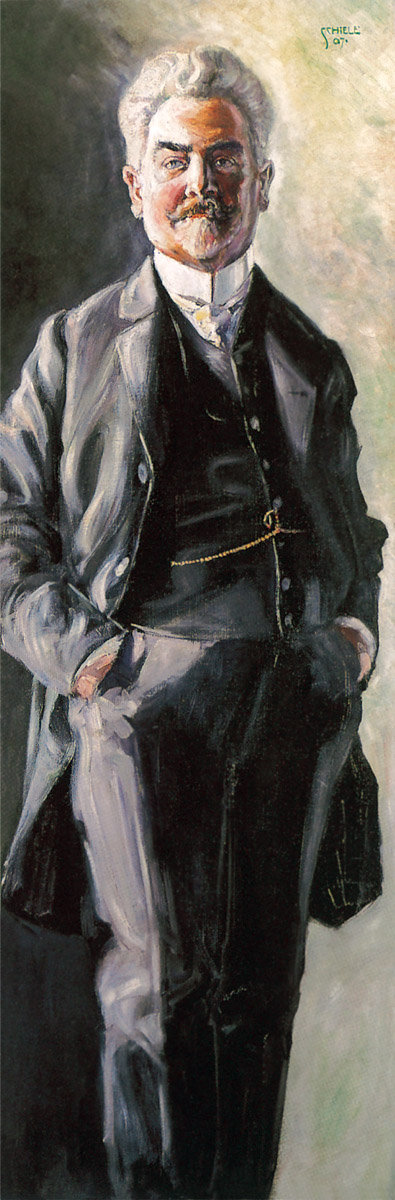

Gustav Klimt, the Father Figure

In 1907, Schiele made the acquaintance of Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), who became his father figure and generously supported the talent of the young genius for the rest of his life. They exchanged drawings with one another and Klimt even modelled for Schiele. In his career, Klimt profited from the large volume of commissioned work, such as the 34.14-metre long Beethovenfries created for the faculty. Nevertheless, he ran into misunderstanding about the central motif of a nude couple embracing from his contemporaries. Criticism of Klimt became more vehement when the periodical Ver Sacrum published his drawings and was confiscated by a public prosecutor because “the depiction of the nude grossly violated modesty and, therefore, offended the public”. Klimt answered that he wanted nothing to do with stubborn people. What was decisive for him was who was it to please? For Klimt, who was supported by private patronage, this meant his clientele of Viennese middle-class patrons.

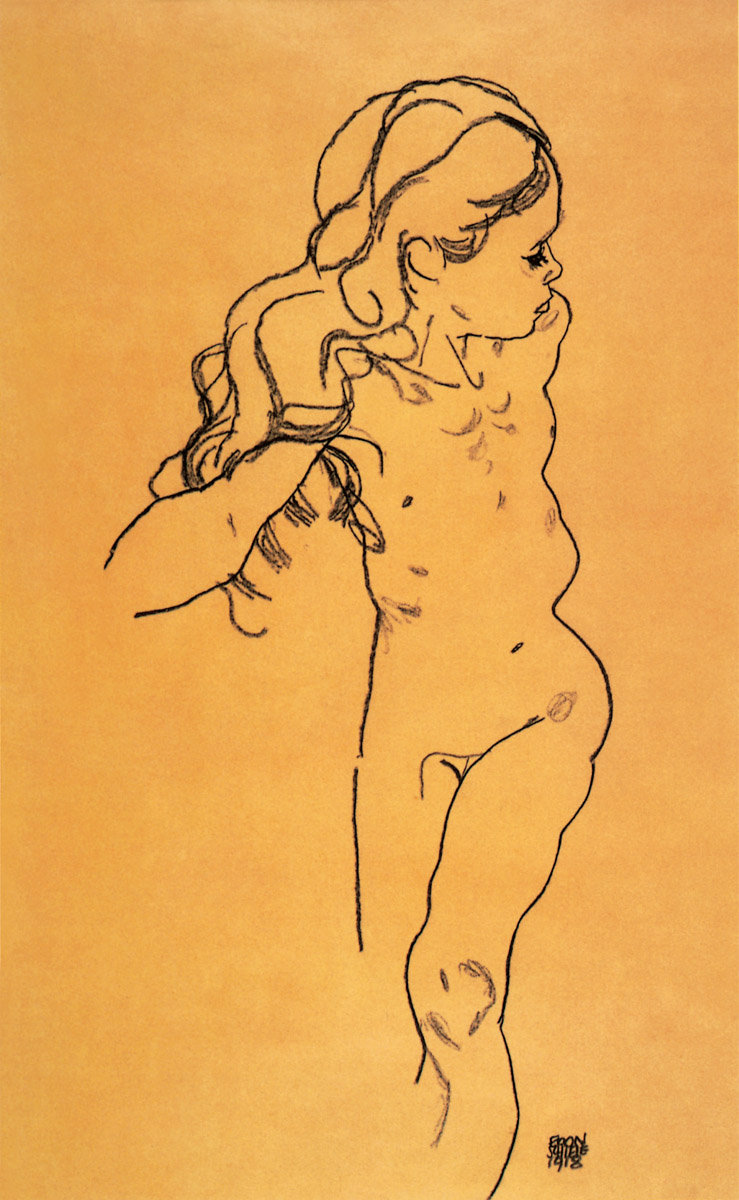

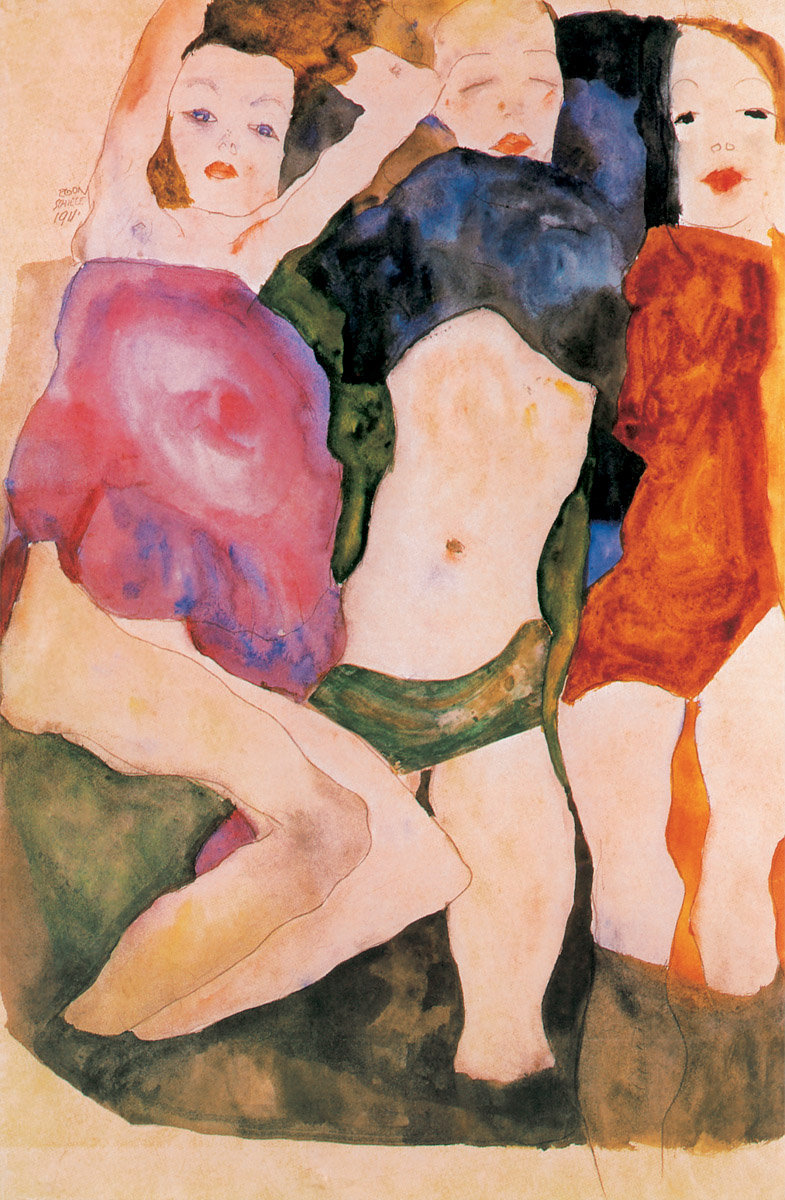

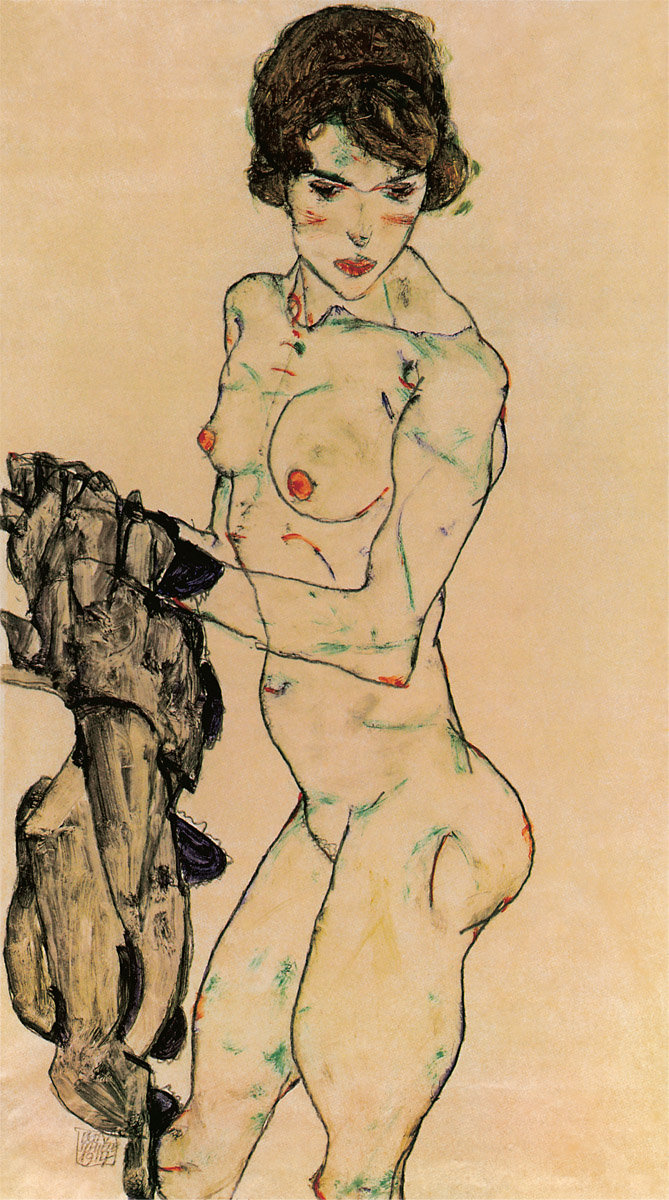

Schiele’s Models

Unlike Klimt, Schiele found his models on the streets: young girls of the proletariat and prostitutes; he prefered the child-woman androgynous types. The thin, gaunt bodies of his models characterized lower-class status, while the full-bosomed, luscious ladies of the bourgeoisie expressed their class through well-fed corpulence. Yet, the attitude of the legendary Empress Sissi is symptomatic of a time in which the conventional image of woman began to change. She indeed bore the desired off spring, however, she rebelled against the maternal role which was expected of her. The ideal of a youthful figure nearly caused her to become anorexic. At the same time, she shocked Viennese court society not only with her unconventional riding excursions, but also in that she wore her clothing without the prescribed stockings.

Around the time of the fin de siècle, Schiele portrayed young working class girls. The number of prostitutes in Vienna ranged among the highest per capita of any European city. Working class women were where upper-class gentlemen found the defenseless objects of their desire, which they did not find in their own wives. The young, gaunt bodies in Schiele’s nude drawings almost stir pity; red blotches cover their thin skin and skeleton-like hands. Their bodies are tensed; however, the red genitalia are full and voracious. Like little animals, they lie in wait for the lustful gaze of the beholder. Despite their young age, Schiele’s models are aware of their own erotic radiance and skillfully know how to pose. The masturbating gesture of the hand on the vagina accompanies the provocative gaze of the model. Contrary to the hygienic taboos of the upper class, for example; not to linger overly long while washing the lower body and not to allow oneself to be viewed in the nude, Schiele’s drawings testify to a simple body consciousness and a matter-of-fact attitude. For the lower levels of society, love for sale pertained to earning one’s daily bread, dealt with sexuality. Outraged, the Viennese public lashed out at Schiele, stating that he painted the ultimate vice and utmost depravation, while he confronted both male and female spectators with their own, hypocritical sexuality. In a letter he wrote: “Doing an awful lot of advertising with my prohibited drawings” and went on to cite five notable newspapers which referred to him. Were his nude drawings but a sales strategy that helped drawing attention to himself? Klimt’s picture of woman is based on the analogy of the female body as a personification of nature. Curled tresses become stylized plant formations and the wave-like silhouette melts into a consecrated atmosphere.

Schiele, however, broke with the beautiful cult of organic art nouveau ornamental art. It is here, where Klimt offended the authorities in various episodes, namely in violating modesty, that Schiele found his main objective. He bared his models of every decorative accessory and concentrated solely on their bodies. Yet, in contrast to the academic nude drawings, which mainly limited themselves to a neutral portrayal of anatomy, Schiele showed erotically-aroused bodies. He knew of the erogenous function that charms the eye and sets erotic signals with red painted lips, fleshy labia and dark moon circles under the eyes. The One Contemplated in Dreams opens her vulva.

The Artist’s Mother, Sleeping, 1911. Watercolour and lead, 45 x 31.6 cm. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

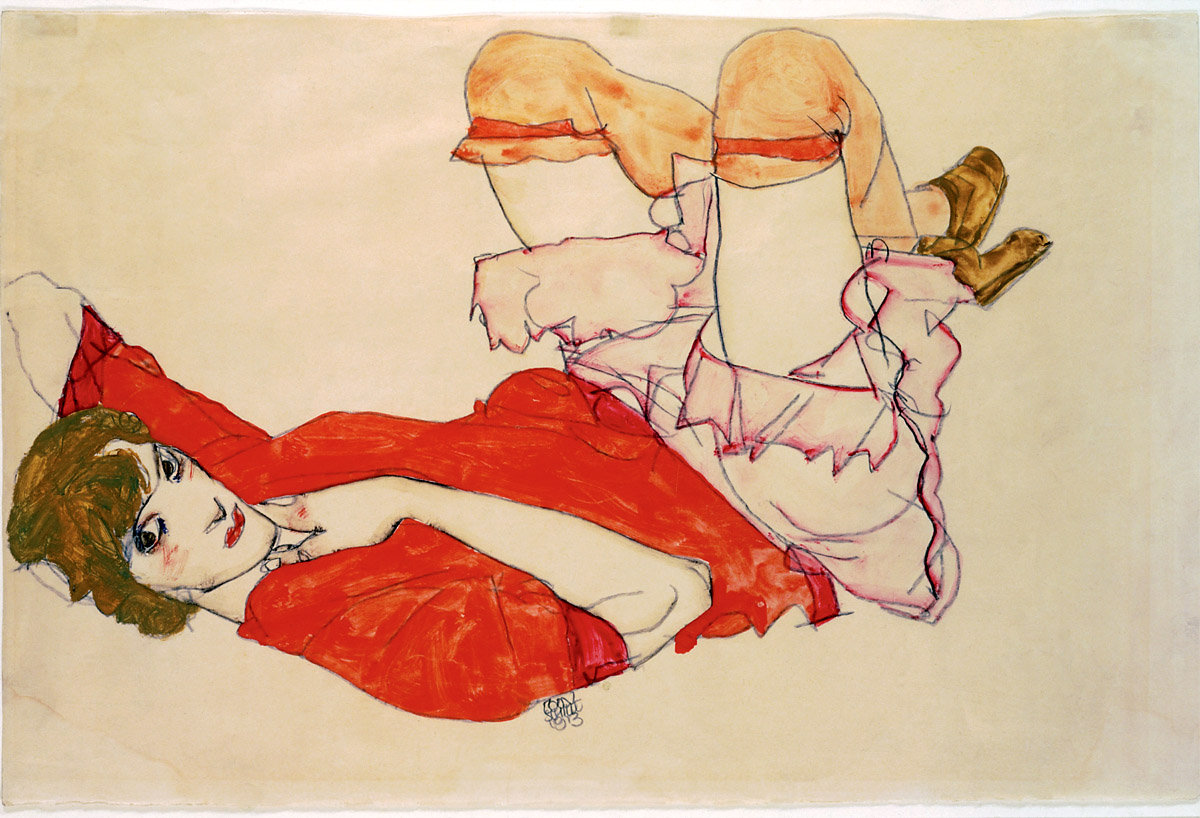

Wally in Red Blouse with Raised Knees, 1913. Gouache, watercolour and pencil, 31.8 x 48 cm. Private collection.

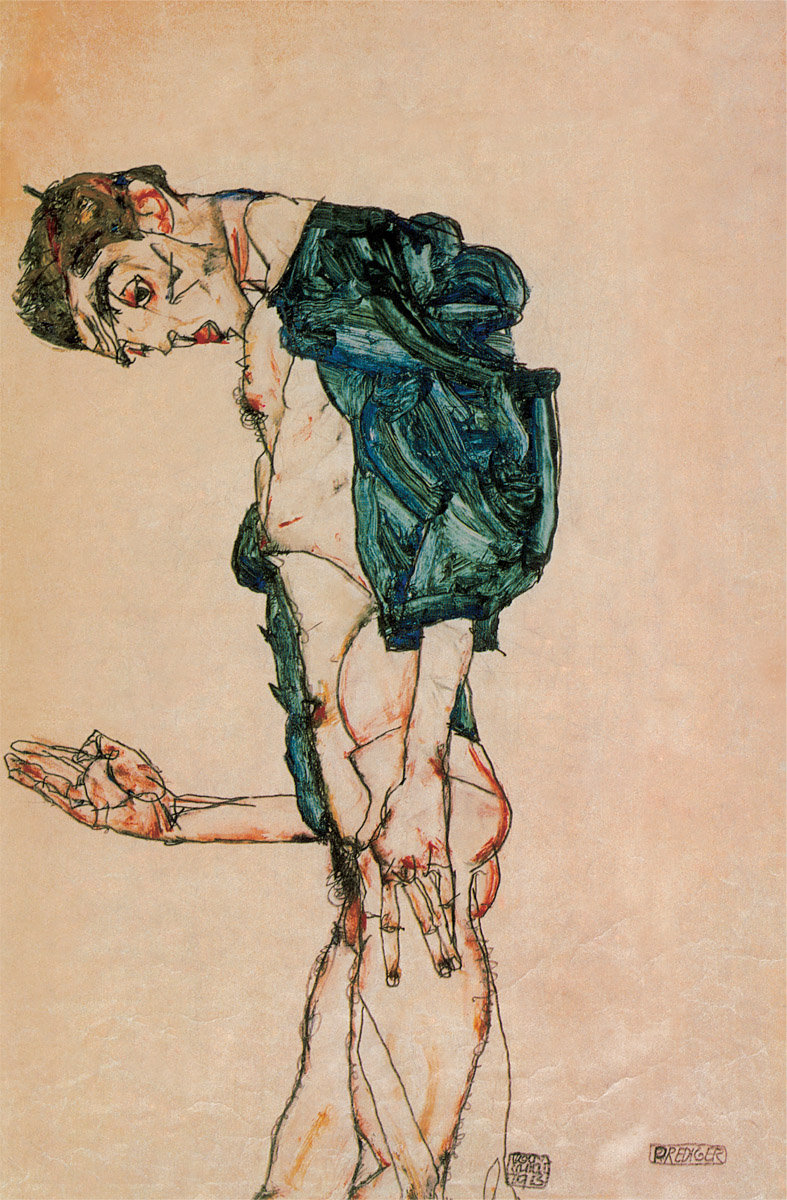

Expressive Art Process

Drawings served Klimt as preliminary studies for his paintings. In contrast, Schiele signs his watercolour sketchs as finalized works of art. It is precisely the sketch-like, unfinished product that characterized Schiele, who unfolded the art process even in his oil paintings. In contrast to the ornamental surface decoration in art nouveau painting, his sharp line executions and jagged aggressive style suggest the artist’s subjective guiding hand.

Encounter with the Mirrored Image

The contour line captures the physical presence and becomes a sculpture-like containment within space. Thereby Schiele dispensed with every spatiotemporal specification. Like a person regarding himself in a mirror, only seeing his face and body, like a lover who, within the body of his love, forgets the world around him, Schiele created his self-portraits before a mirror, as well as some of his female nude drawings. Schiele, Drawing a Nude Model in front of a Mirror illustrates this. The scene is illuminating, the duplication of frontal and rear views of the nude woman are revealed in the reflection, however, there, where the mirror is, stands the viewer. He functions as the mirror in which the model regards herself, reassuring herself of her body, and in whose gaze it moves. The intimacy between painter and model is countered in relationship to viewer and drawing.

First Exhibitions

In 1908, Schiele took part in a public exhibition in the imperial hall of the Klosterneuburg Monastery for the first time. He exhibited small-scale landscapes which he had painted from summer through to the autumn (Village with Mountains, Landscape in Lower Austria). According to Jane Kallir, around the end of 1908, Schiele had painted nearly half of all the oil paintings of his lifetime. It was only in 1909 that Schiele’s artistic creativity reached a great turning point. He left the academy and the reactionary professor Christian Griepenkerl, and established together with Anton Peschka, Albert Paris von Gütersloh, Anton Faistauer, Sebastian Isepp, Franz Wiegele and others from the “New Art Group” (Neukunstgruppe). The theme of the new artists was ‘opposition’.

Schiele’s retreat from the subjective experience of the individual was a counter-reaction to Viennese historicism and its prince of painters, Hans Makart, celebrated by the government. Schiele distanced himself from their allegoric similes. He turned Catholicism’s conventional values upside down and placed them in the service of sexuality. His strategy: he wanted to shock. In the painting provocatively titled The Red Communion Wafer, Schiele reclines on his back in an orange shirt with his abdomen bared, his spread legs suggesting the feminine gesture of submission, while before him, gazing at the viewer, a nude strawberry-blonde holds his enormous phallus.

In other paintings, monks make love to nuns and expectant women who were often unwelcome and repudiated by strict Viennese society. “The nun prays chafed and nude before Christ’s Agony on the Cross” (Georg Trakl, Munich, 1974). Furthermore, Schiele painted homosexual couples, transgressing taboos and provoked the fantasies of his contemporary viewers. In turn, Schiele found acknowledgement at the international art show in Vienna where he was represented by four paintings next to the expressionist works of Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch and Oskar Kokoschka. He made the acquaintance of Josef Hoffman, the director of the Vienna workshop. In December of 1909, the first exhibition of the “New Art Group” took place at Pisko’s fine art dealership.

Vienna Art Scene

By 1909, thus relatively early, Schiele had made the acquaintance of decisive personalities of the Viennese art scene, whose portraits he painted and who were to remain loyal to him for his entire life and beyond. Schiele made the acquaintance of Arthur Roessler, writer and art critic, who became one of his most decisive friends and promoters. Further figures who influenced his career were Eduard Kosmack: the publisher of the magazines The Architect and The Interior, Carl Reininghausen (1857-1929), who was one of the most important Viennese collectors and the railroad official and Schiele collector Heinrich Benesch (1862-1947), who later dedicated a book to Schiele.

Portrait of a Woman (The Dancer Moa), 1912. Pencil, 48.2 x 31.9 cm. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

Self-portrait with Lavender Shirt and Dark Suit Standing, 1914. Pencil, watercolour and gouache on paper, 48.4 x 32.2 cm. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

Schiele’s Close Circle of Friends

Perhaps because Schiele opposed the plans of his uncle who would have liked to persuade his ward to enter military service, Czihaczec withdrew his guardianship in 1910. During the same period, the incident with the mysterious lover occurred, of which, with the exception of an exchange of letters with the gynecologist Erwin von Graff who assured Schiele that he had admitted her to his clinic and was attending to her, nothing is known. Schiele dealt with this incident in several paintings: Birth of the Genius and The Dead Mother. He painted a foetus, which, still in its mother’s womb, stares at the viewer.

During this time, love and death studies went hand-in-hand. On the one hand, the sexual act is associated with the danger of pregnancy and the possibility of dying in childbirth. The life-giving body may be destroyed by death. On the other hand, syphilis lurked in every kiss. Is it possible to explain the subliminal, morbid trait in Schiele’s world? The role of woman was limited solely to her biological function of childbearing in the cult book of that time by the author Otto Weininger, Sex and Character, who commented that men of significance should only get involved with prostitutes. Whereas Freud discovered: “Their upbringing denies women the ability to deal on an intellectual level with sexual problems. Which is where they have the greatest need for knowledge, yet society reacts with condemnation of this desire for knowledge as unfeminine and as a sign of a sinful predisposition.” Freud attributed the alleged intellectual inferiority of women to sexual repression, which resulted in inhibition of thought.

Accompanied by his friend, the painter and mime Erwin Osen, Schiele fled to Krumau where they spent the summer with a dancer named Moa (Portrait of a Woman (The Dancer Moa), 1912; The dancer Moa, 1911; Moa, 1911), the lover of Osen. There, Schiele also made the acquaintance of the young baccalaureate Willy Lidl, who avowed his deep love for him. Back in Vienna, Schiele shared his atelier with Max Oppenheimer (1885-1954). Day in, day out, he lived from hand to mouth. Even if young Schiele lamented his financial woes, he quickly managed to get on his feet again and find support from friends and patrons. Then, in 1910, Vienna workshops, established in 1903, printed three of Schiele’s picture cards; at the same time one of his paintings was shown at the international hunters’ exhibition in the context of the Klimt group. A further exhibition at the Klosterneuburg monastery exhibited the Portrait of Eduard Kosmack and that of a boy, Rainerbub, son of the Viennese orthopedist and surgeon Max Rainer (1910). As early as 1911, the first monograph on Schiele, penned by the artist and poet Albert Paris von Gütersloh, was published. In the same year, Arthur Roessler reviewed Schiele’s works in the monthly periodical Bildende Künstler. In Vienna, Schiele took part in the collective exhibition at the Miethke Gallery.

Wally, His First Love

Once again, Schiele wanted to get away. “Vienna is full of shadows, the city is black. I want to be alone [in]to the Bohemian Woods, that I need not hear anything about myself,” he wrote in his diary. Wally (Valerie Neuzil), former model and lover of Klimt who supposedly gave herself to Schiele, accompanied him. They moved to his mother’s home town in Krumau on the Moldau. The devoted Lidl had procured an atelier with a garden. A very productive working phase began for Schiele. Besides a few landscapes, he mainly worked on nude studies of himself and Wally, his “twittering lark”. Like the diary drawings, numerous studies depict the erotic cohabitation of two bodies.

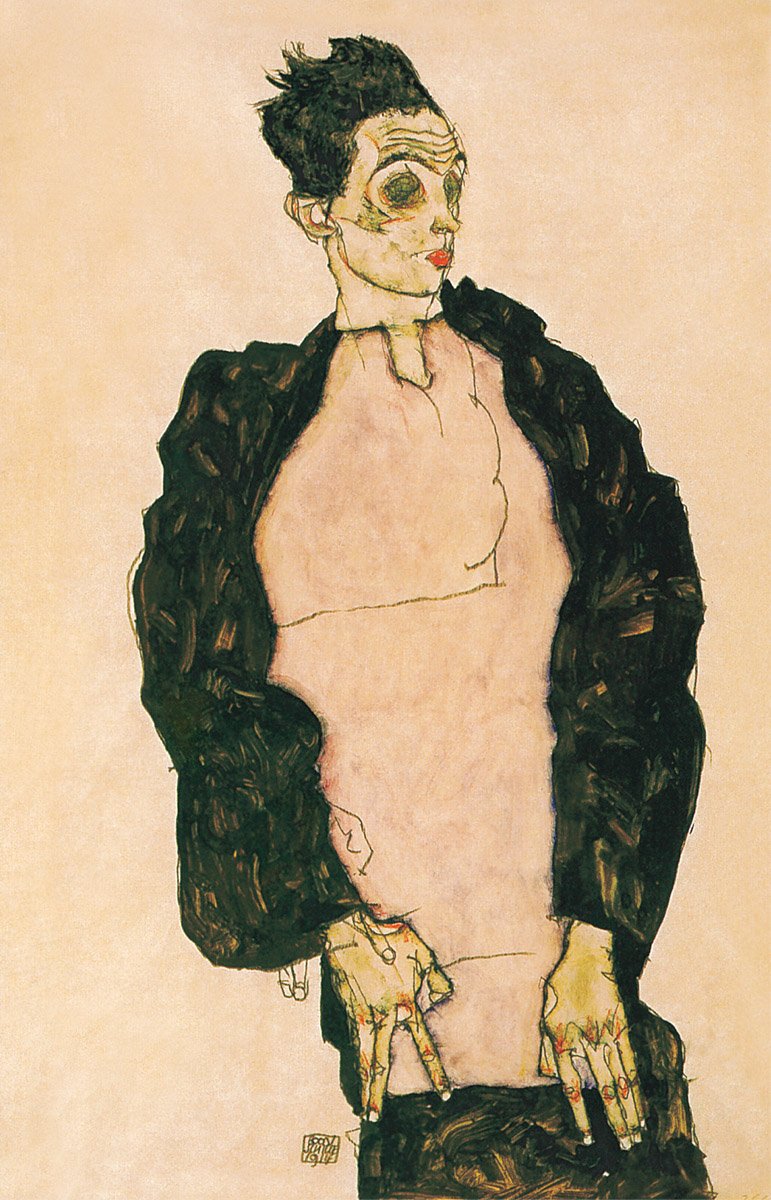

Self-portrait as Nude Study

There are approximately 100 self-portraits including several nude studies of Schiele. Study of the male nude was obligatory at the academy, psychological self-portraits, however, apart from Richard Gerstl in 1908, were the exception. The self-portrait as nude study positions the artist not only as a person of sight, but also in his physical being. Schiele did not act as a voyeur in baring his models, rather, he brought himself into play. The nude study depicting a rigid member in the act of masturbation went a step further and shows he was a man fascinated by his own sexuality. This reversal in passivity accompanies the setting of a new goal: to be looked at. The urge to look is indeed autoerotic from the beginning; it surely has an object but finds it in its own body. In turn, showing the genitals is well known as an apotropaic action. Accordingly, Freud interprets “the showing of the penis and all its surrogates” as the following statement: “I am not afraid of you, I defy you.”

Nude Self-Portrait, 1910. Watercolour, gouache and black crayon with white highlights, 44.9 x 31.3 cm. Leopold Museum, Vienna.

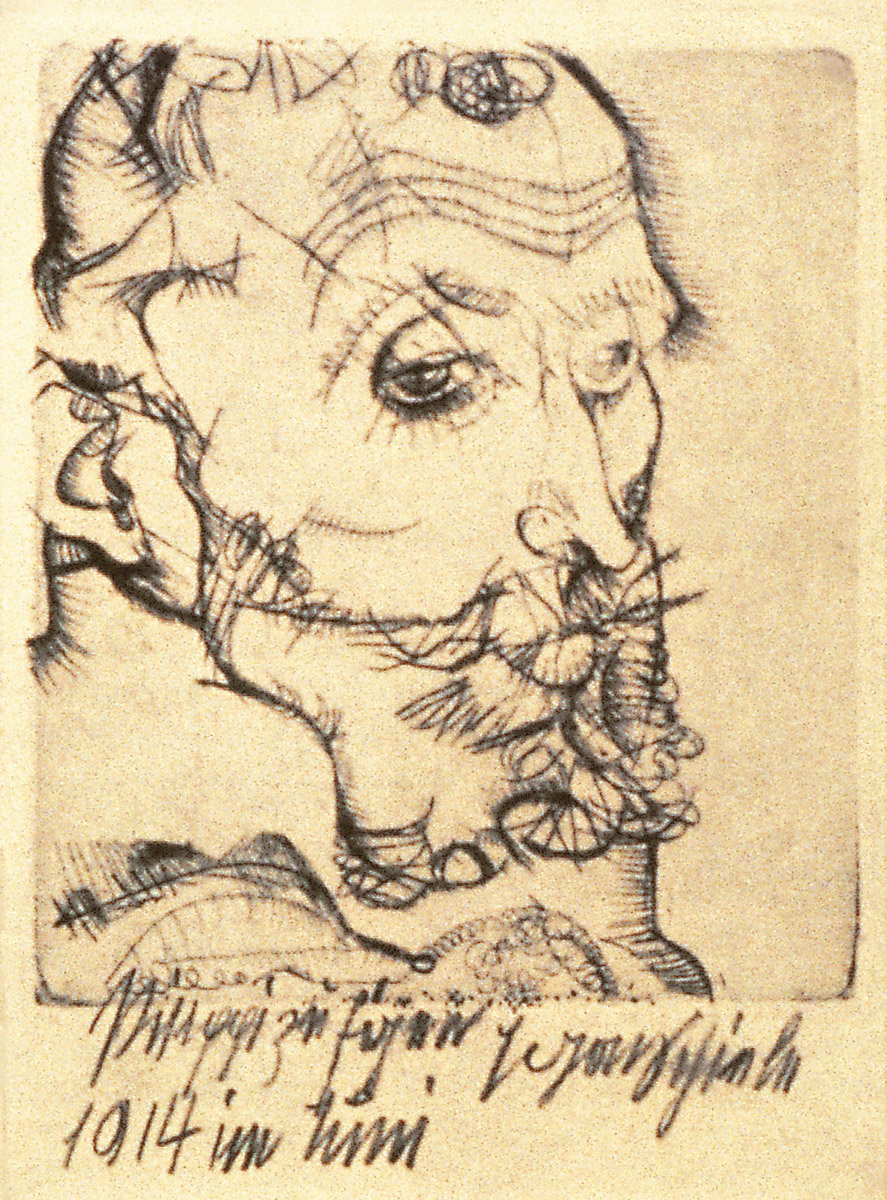

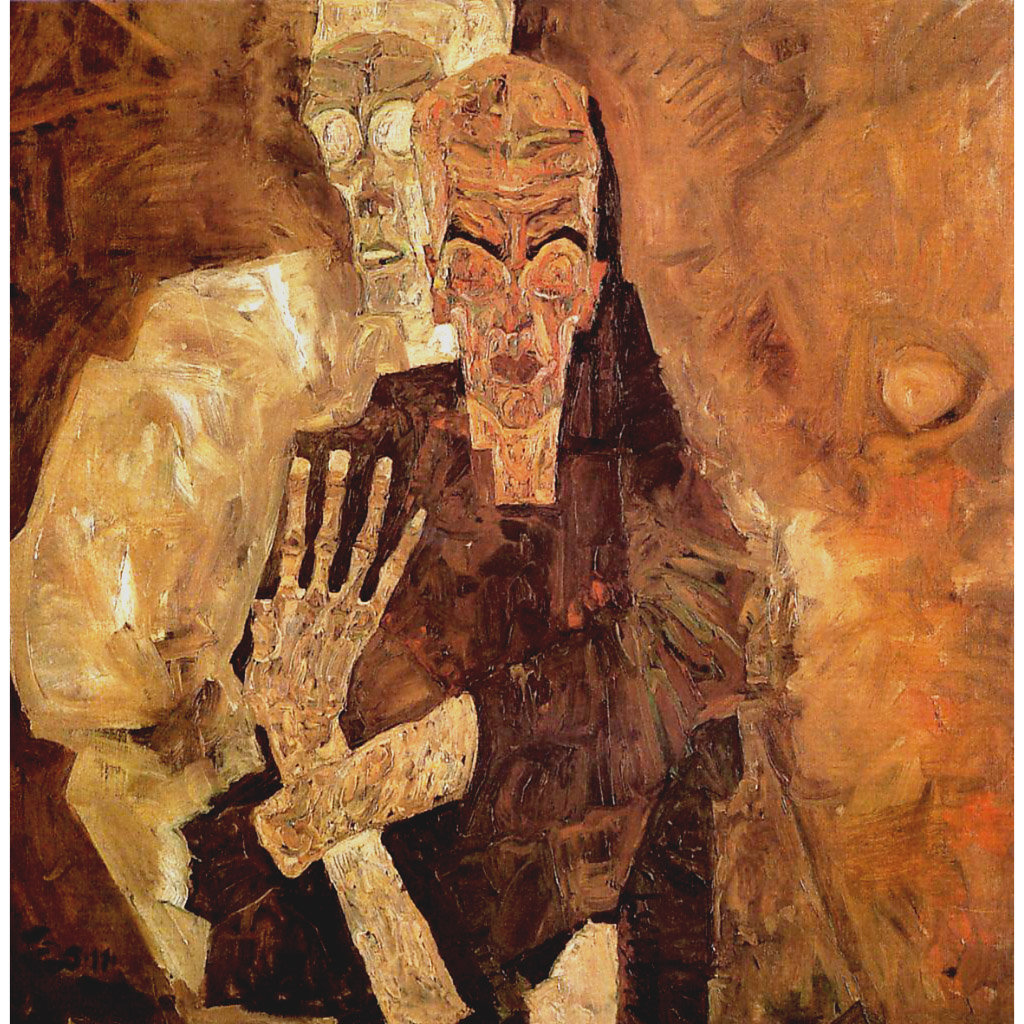

Schiele, the Man of Pain

The discrepancy between Schiele’s external appearance and his repulsively ugly self-portraits is astonishing. Gütersloh described Schiele as “exceptionally handsome”, of well-maintained appearance, “someone who never had even a day-old beard”, an elegant young man, whose good manners contrasted strangely with his reputedly unpalatable manner of painting. Schiele, on the other hand, painted himself with a long high forehead, wide opened eyes deep in their sockets and a tortured expression, an emaciated body, which he sometimes mutilated up to its trunk, with spider-like limbs. The bony hands tell of death at work. His body reflects the sallow colours of decay. In many places, he painted himself with a skull-like face. Schiele admitted in a verse: “everything is living dead”. Just as Kokoschka maintained, Schiele soliloquized with death, his counterpart. “And surrounded by the flattery of decay, he lowers his infected lids” (Georg Trakl, Munich, 1974).

At the same time, Schiele perceived himself as a man of pain: “That I am true I only say, because I … sacrifice myself and must live a martyr-like existence.” If contemporary art banished religious themes from its field of vision, the artist now incarnated these himself. In a letter to Roessler the Christ-likeness becomes clearer still: “I sacrificed for others, for those on whom I took pity, those who were far away or did not see me, the seer.” His fate as an outsider led to the ideal of the artist as world redeemer. In the programme of the New Artists he explains: “Fellow men feel their results, today in exhibitions. The exhibition is indispensable today … the great experience in the existence of the artist’s individuality.” For him, however, this no longer concerned illustration, rather it was a representation of his soul’s inner life. The nude study is a revealing study. Thereby, the work in its expressive self-staging becomes a study of his life.

Fascination with Death

The Viennese at the turn of the century lived with a longing for death and romanticized the “beautiful corpse”. “How ill everything coming into being does seem to be,” wrote Trakl, who in 1914 found death at the front. Schiele shared with Osen, who had himself locked away in a Steinhof insane asylum where he might study the behaviour of the patients there, an interest in pathologic pictures of disease. In the clinic of the gynecologist Erwin von Graf, he studied and drew sick and pregnant women and pictures of new and stillborn infants. Schiele was “fascinated by the devastation of foul suffering, to which these innocents were exposed.

Astonished, he saw unusual changes in the skin in whose sagging vessels thin, watery blood and tainted fluids trickled sluggishly, he marvelled also at light-sensitive green eyes behind red lids, the slimy mouths and the soul in these unsound vessels,’’ reports Roesseler. Therein he resembled Oskar Kokoschka, called the “soul slasher” and of whom it was said that “painting hand and head, he lay bare in a ghostly manner the spiritual skeleton of her whom he portrayed”. To the colour lithograph of his drama, Murder Hope of Women, he commented: “The man is bloody red, the colour of life, but he lies dead in the lap of a woman, who is white, the colour of death.” Man and woman in the dance of life and death.

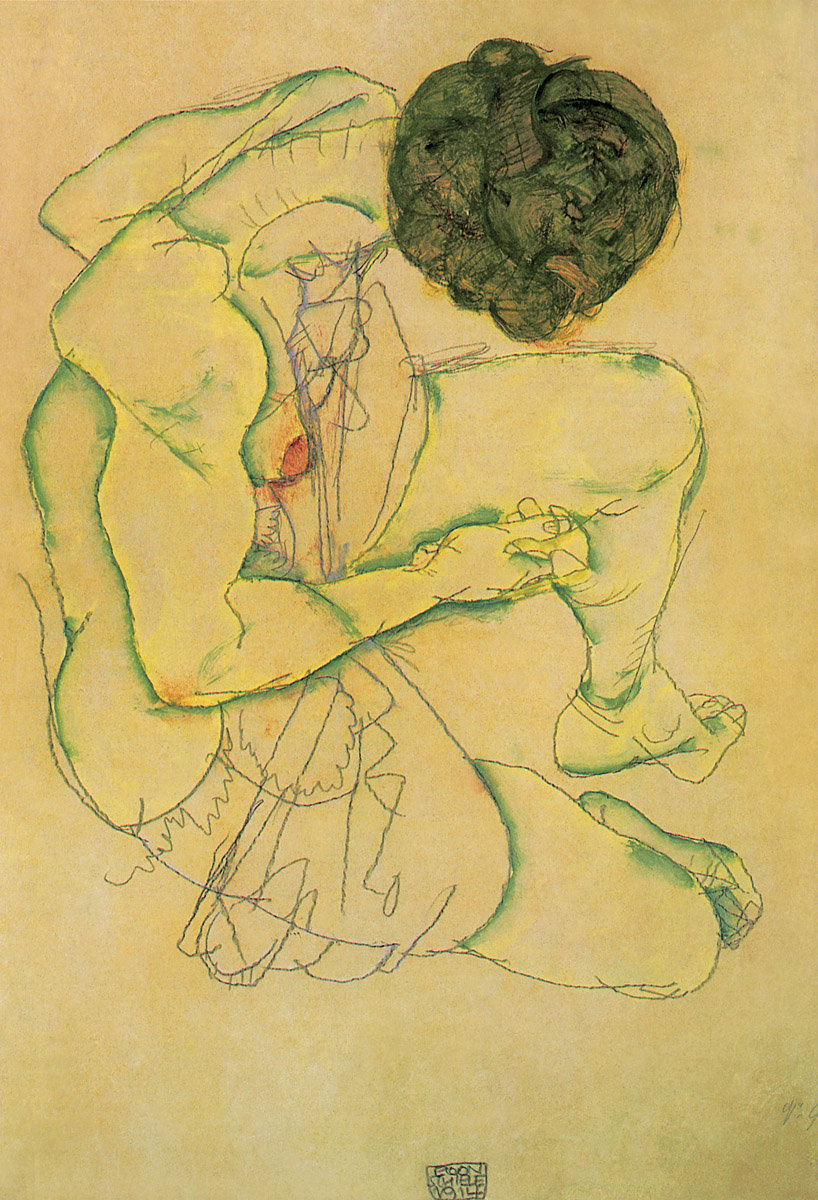

Phantom-Like Creatures

With a few lines, Schiele sketched the outlines of the body on paper. A thigh is reduced to two lines. The stroke is dynamic, grows fainter, following the structural ductility of a fast thrown-in movement. Jagged, with hard angles he loves the bone structure. Schiele’s strokes are like calligraphy, which captures the body’s expression in just a few lines. In contrast to the reluctant, bony aspect of the shoulders and pelvis is the round diffraction of the chest. Orange nipples and vulva become wounds. The physiognomy of his models, however, remains anonymously phantom-like, the button eyes could sooner belong to a doll, which could be any woman. The body posture is directed at the gaze of the viewer, before whom she exhibits her genitals. The splayed gesture of the hands is peculiar: these appear intractably hard and call to mind the hands of Schiele.

Two Girls Embracing (Friends), 1915. Gouache, watercolour and pencil, 48 x 32.7 cm. Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest.

Body Perspectives

Schiele ignored light and shadow effects which model the body, dispensed with shadow strokes and divests the character of all spatial containment. In his atelier, he often worked on a ladder from where he captured his models from a bird’s eye view perspective in an extreme visual angle of under and oversight. This calls to mind one of his verses: “An intimate bird sits in a leafy tree, he is dull coloured, hardly moves and does not sing; his eyes reflect a thousand greens.” He isolated the creatures in his view, set them in a world without time or place. Bodies form space. An example of the spatial lack of orientation of his subjects is the commissioned artwork for Friederike Maria Beer, the fashion conscious daughter of a cabaret proprietor who actively followed Viennese art events.

On Schiele’s suggestion, she allowed her full body likeness to be painted on the ceiling. It shows her in a colourful patterned dress in a rigid pose, her body strangely floating, free of all gravitational pull, her raised arms with the indefinable hand gesture call to mind Schiele’s self-portraits once again.

Vampire-Like Trait of the Sex

Ulrich Brendel wrote in the periodical Die Aktion that Schiele captured “the vampire-like trait of the sex”. His models lamented: “It is no pleasure; he always sees only the one thing.” At the same time, Freud discovered the fear of castration mechanism: “the sight of Medusa’s head, that is to say, that of the feminine genitalia, causes one to become rigid with fright, transforming the beholder into stone. To become rigid symbolizes the erection.” A girl, her face remaining anonymously sketch-like, reclines backwards; her uplifted skirt is pleated out of which her genitals peek, becoming an inner eye slit. Again and again, Schiele discovers and sees, shows and offers the most intimate, forbidden part to the viewer. He carefully paints it in watercolours, a calyx of orange colour like a fruit.

Disgust and Allure

Schiele scarcely modelled the bodies he painted, only a few coloured splotches animate the white paper surface on which the body seems to lie confined by a few lines. Schiele’s patron, Carl Reininghausen, whom Schiele instructed in drawing and painting, complained that he “paints so casually that the composition is no longer recognizable in places due to the splotches”. The marks on the body executed by the use of a wash are astonishing; often in contrasting colours of green and red, they create aggressive tension. In contrast to the general impression of the shape, the splotches point to a closer view, this intimacy exposes the condition of the skin. Schiele’s models do not possess unblemished white, alabaster bodies, rather, he gets under their skin. “The body becomes a wound.” (Werner Hofmann, Munich, 1981) Schiele turns the fleshy inner part of the vagina inside out.

As to the aesthetics of the colour splotches which like the famous blotch paintings by Rorschach render the viewer a surface to project onto, Hugo von Hofmannstal wrote that “art is magical writing, which uses colours instead of words to portray an internal vision of the world, a puzzling one, without being”. Other contemporaries, however, described Schiele’s art as “manically demonic”. “Some of his pictures are materializations of obscured consciousness, of apparitions grown bright.” His friend Roessler in turn stressed that his face is the synthesis of inner human existence. Doubtless, the nude studies reflected the inner world of the soul’s condition imposed onto the model by the artist. “I am everything at once, but never shall I do everything all at once,” declared Schiele who incorporated psychological role-play into the paintings of his models. Schiele tried to capture his own psychological experience.

The Age of the Pornographic Industry

In the year 1850, with the invention of photography, in particular the daguerreotype, pornographic photographs also came into fashion. On the one hand, the photographs served as a model for artists, also for Schiele who took many photographs of his models. On the other hand, they were collected by erotomanics. Mainly, however, they were used as presentation cards at bordellos by means of which the visitor could compile his “menu”. The production of erotic pictures was not prohibited, though advertising them was. The models as well as the photographer risked going to jail. The first conviction was made in 1851. When 4,000 obscene prints and four large albums of “nude women” were discovered in the possession of the French photographer Joseph-Antoine Belloc, he received a minor sentence of three months detention.

The models were usually prostitutes, pliant women, but also working women in dire financial straits and gutter children picked up from the streets. To satisfy voyeuristic desire, the Munich publisher Guilleminot Recknagel had a stock of 4,000 photographs of models aged from ten to thirty years old. Around 1870, erotic postcards came into circulation. Thematic scenes from Greek and Roman mythology, heroic or Christian martyr scenes with a naked Magdalene, crucifixion of female characters and nude Greeks were portrayed. In provincial theaters, these pictures were very popular. Famous collectors were the Marquis of Byros in Vienna and in Munich Doctor Kraft Ebbing. Baron von Meyer loved the “sweet girls” from Vienna. Schiele surely profited from the high sales of pornographic photographs in direct relation to lustful consumption. Yet, his erotic drawings testify to a personal question which in turn is embodied in this decadent epoch, namely the dialectics of carnal desire and the death instinct.

Standing Nude with Blue Sheet, 1914. Gouache, watercolour and pencil, 48.3 x 32 cm. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

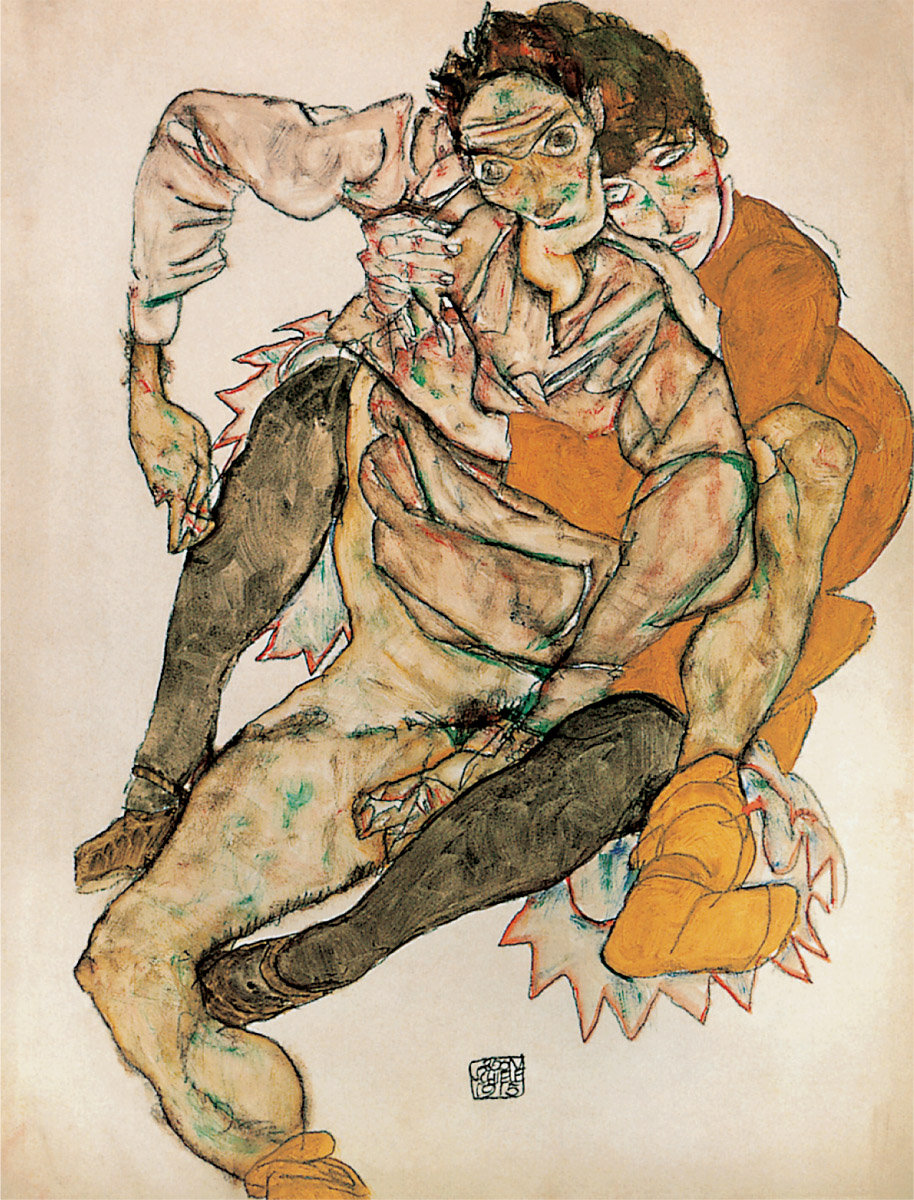

Seated Couple (Egon and Edith Schiele), 1915. Pencil and gouache on paper, 52.5 x 41.5 cm. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

Two Girls on Fringed Blanket, 1911. Gouache, watercolour, ink and pencil, 56 x 36.6 cm. Private collection, courtesy of St. Etienne Gallery, New York.

Seated Woman in Violet Stockings, 1917. Gouache and black crayon, 29.6 x 44.2 cm. Private collection.

Reclining Nude with Spread Legs, 1914. Gouache and pencil, 30.4 x 47.2 cm. Graphisches Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

Schiele’s Arrest

In August 1911, Schiele felt impelled to relocate to Neulengbach near Vienna in Lower Austria with Wally. His retreat to the country was naïve and out of touch with reality. Inevitably, he would offend the conservative population in the countryside with his unorthodox life style. Living in sin with the still under-age Wally would rile the population of the provincial town against Schiele. For the village youth, however, Schiele’s studio was a haven of well being. Gütersloh described the free-spirited atmosphere: “well, they slept, recuperated from parental thrashings, lazily lolled about, something they were not permitted to do at home”; until April 13, 1912, when a catastrophic incident occurred.

The father of a thirteen-year-old girl, who had run away from home and found refuge in Schiele’s home, reported him for kidnapping. The charge was withdrawn, but Schiele was arrested and charged with endangering public morality and with circulating “indecent” drawings. Schiele’s defense by Heinrich Benesch, however, was naïve. Benesch wrote: “Schiele’s carelessness is responsible for the incident. Whole swarms of little boys and girls came into Schiele’s studio to frolic. There, they saw the nude study of a young girl.” For the sake of his art, Schiele forgot all modesty, lifting the skirts of the sleeping children, and surprising two girls embracing one another. Exposure of his own private sphere as well as that of others became a confession-like, artistic expression of his own truthfulness. The private sphere and public domain became interchangeable. Schiele’s influential collector Carl Reininghausen procured an attorney in Vienna for him, but at the same time dispenses with the “cordial you” (informal) between them. In St. Pölten, Schiele spent 24 days in custody.

He pleaded: “To inhibit an artist is a crime. It is called murder of life coming into being”. The prison stay validated him, the artist, in his role as an outsider. Several self-portraits of Schiele as a prisoner testify to this time. Solemnly the judge burnt one of the indecent drawings in the courtroom. Schiele’s reply was: “I do not feel chastised, but cleansed.”

International Artist

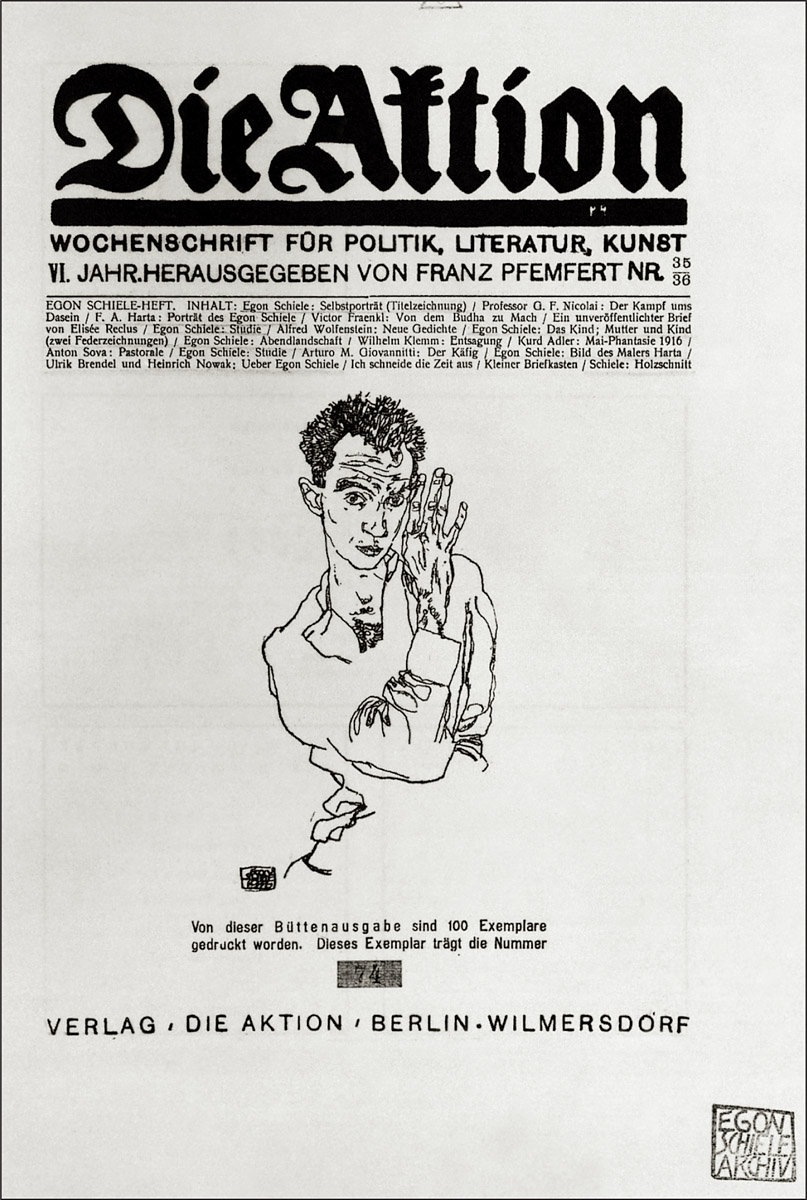

In Munich, the art dealer Golz exhibited Schiele’s works. 1912 was a critical year, the “New Art Group” together with the artists union displayed Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in Budapest, Munich and Essen. In November, 1912, Schiele returned to Vienna and moved into an atelier in the Hiertzinger Hauptstrasse. Klimt introduced him to the collector August Lederer whose son Erich became his pupil. Franz Pfemfert published poems and drawings by Schiele in the Berlin periodical Die Aktion. Three of Schiele’s works could be seen in the international special alliance exhibition in Cologne. The lithograph Male Nude Study appeared in the Sema-Mappe (portfolio) of the Delphin Publishing House in Munich.

In 1913, Schiele became a member of the Bund Österreichischer Künstler (federation of Austrian artists), of which Gustav Klimt was president. In the same year, he went to Munich, where he took part in a collective exhibition at the Galerie Golz. On July 28, 1914, war was officially declared between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Serbia. Schiele commented: “We live in the most violent time the world has ever seen. Hundreds of thousands of people perish miserably, everyone must bear his fate either living or dying; we have become hard and fearless. That which was before 1914 belongs to another world.” Schiele continued with his work, he was now an internationally recognized artist who had exhibitions in Rome, Brussels and Paris. Anton Josef Trèka (1893-1940) photographed Schiele in extravagant pantomime poses. In the Berlin periodical using gestures like sign language, Die Aktion, he wrote: “We are above all people of the times, in other words, such who have at the very least found the way into our present time.” In 1915, the Viennese Galerie Arnot displayed an exclusive exhibition of sixteen paintings, watercolours and drawings by Schiele, among them, Schiele’s Self-portrait as St. Sebastian. With this religiously engaged role model, he stands in the tradition of Oskar Kokoschka, Rainer Maria Rilke and Georg Trakl, who saw themselves as martyrs tormented by society, yet at the same time, Schiele held the reins of his career adroitly in his hands.

Schiele’s Socially Advantageous Marriage

Schiele’s beloved sister Gerti married a fellow artist, Anton Peschka; their young son often spent time with his uncle. Across from Schiele’s atelier lived his landlords, the middle-class Harms family with their two young daughters. Schiele, disguised as an Apache, allowed them to see him at the window. Later, he sent Wally with an invitation to the cinema and the assurance that she too would accompany them. The two sisters modelled for Schiele and, in their vanity, competed for the favours of the young artist. Coldheartedly he informed Wally that he would marry Edith, a socially advantageous match for him, whereupon she joined the Red Cross as a nurse and went to the front where she would succumb to scarlet fever in 1917. In the allegorical painting Death and the Maiden, Schiele himself came to terms with his separation from Wally.

The Bourgeois Schiele

On June 17, 1915, five days after his twenty-fifth birthday, Schiele married Edith Harms. Four days later he was inducted into military service in Bohemia. In 1916, he was held captive in the Russian prisoner of war camp located in Mühlung near Wieselburg. Die Aktion published two xylographs. One year later, Schiele returned to Vienna to work in the army museum. At first, his wife was his exclusive model. However, as she grew plumper, Schiele once again began to look for models elsewhere. In 1918, 117 sessions with other models were recorded in his notebook. The Vienna book dealer Richard Lanyi published a portfolio with twelve collotypes of Egon Schiele’s drawings. In December, Schiele worked for the periodical The Dawn. In a letter dated March 2, 1917, Schiele wrote to his brother-in-law: “Since the bloody terror of world war befell us, some will probably have become aware that art is more than just a matter of middle-class luxury.”

Schiele, a Celebrated Artist

After the sudden death of Klimt and the exile of Kokoschka, Schiele was the most famous artist in Vienna. He exhibited 19 large paintings and 24 drawings in the 49th Vienna Secession of 1918. Franz Martin Haberditzl purchased the Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Seated for the Moderne Galerie. It is the first acquisition of a painting while the Schiele was still alive. However, Schiele had to paint over the plaid skirt, as the museum’s director found it too indecent. Schiele could now afford a larger atelier, the old one was to become an art school. Already in 1917, Schiele had a plan for an art centre where the various disciplines of literature, music and visual art could coexist. The best-known founding members were Schönberg, Klimt, and the architect Hofmann. Death, however, prevented these plans. On October 31, three days after the death of his wife who was six months pregnant, Schiele also died from Spanish flu. Three days later, on November 3, 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire capitulated.

Photograph by Anton Josef Trèka, Egon Schiele on his feet with his arms above his head, 1914. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

Portrait of the Artist’s Wife Standing (Edith Schiele in Striped Dress), 1915. Oil on canvas, 180 x 110 cm. Gemeentemuseum, The Hague.