BORN UNDER A WANDERING STAR (1834-1863)

During the last half of the 19th century, three American artists were to work in Europe, mainly in England and France. Each of them was to play an important role. Mary Cassatt participated in the Impressionist movement in France, John Singer Sargent was to be considered one of the greatest painters of his day, and James McNeill Whistler, to whom this biography is dedicated, was to create a completely original style.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler was born on July 10, 1834 in Lowell, a little town in Massachusetts. His family could trace their origins back to 13th-century England; it was a line full of clerks and soldiers who had settled in the Thames Valley. The American Whistlers were descendant of John Whistler, who belonged to the Irish branch of the family. James’ father was a graduate of the West Point military academy. He took Anna Mathilda McNeill as his second wife. Whistler was a railroad engineer in Lowell, and this is where James and his two brothers were born. In 1842, Nicholas I, Tsar of Russia, chose John Whistler to build him a railroad from St. Petersburg to Moscow and Major Whistler left for Russia. On August 12, 1843, a year after her husband’s departure, Mrs. Whistler and her children took the same route and left for Boston on a journey which at the time was long and dangerous. The Whistlers stayed in London for two weeks, then traveled to Hamburg where they embarked on the steamship Alexandra, bound for St. Petersburg. During the trip, the youngest son fell gravely ill and died. James was nine years old at the time. Despite his strict upbringing, the child encountered many of the influences which were to shape his future career as an artist. He was allowed relative freedom at home. When the town was lit up on winter nights, everyone stayed up late. Ice-skating or canoeing parties were organized and visits from other American families prevented too brutal a feeling of displacement. In the spring of 1844, the Whistlers rented a house by the road to Peterhof, the town which was originally founded as the Tsar’s summer residence, near St. Petersburg. They all went together to Tsarskoye Selo, the “Russian Versailles” which had been built in 1714 by Peter the Great.

Whistler and his family then visited the palace standing in its magnificent park, which was considered among the greatest in the world. Colonel Todd, who represented the American government, took them to visit the palace built by the Empress Catherine. Here they often attended the events held at the Tsar’s court and in the evening the child marveled at the fireworks and the military parades of foot soldiers and cavalry. The Scottish artist Sir William Allen was a frequent visitor to the Whistlers’, and James greatly enjoyed the conversations which he heard in the drawing-room. In her journal, his mother recorded, “Jemmie took such an interest in the discussion that we immediately discovered his passion for art. He had to show his sketches to Sir William Allen.” Once the children were in bed, the painter took Mrs. Whistler aside and confided to her, “Your son has an exceptional talent.” She would later say, “Often, at eight o’clock I was still reading and sewing with a lamp, and I could not persuade James to leave his drawing and go to bed before nightfall.” Of these first attempts there remains a portrait of his aunt, Alicia McNeill, who visited Russia in 1844. From his time in St. Petersburg, Whistler retained a passion for fireworks. He was then a student at the Academy of Science and could only draw in his leisure hours. He and his brother were boarders and only went home on Saturdays. They had to wear a uniform, their short hair topped with a black felt beret. James spent his time drawing and leafing through a large volume of engravings by Hogarth, whom he would always consider to be England’s greatest artist. On March 23, 1847, the major was rewarded for his work by being received by the Tsar. But a cholera epidemic had broken out in St. Petersburg. Mrs. Whistler had to leave hurriedly for England with her children. James was convalescing after a serious attack of rheumatic fever. He spent his time aboard the ship making drawings. In England, the family attended the wedding of Whistler’s half-sister and Seymour Haden (1818-1910), a doctor who was also a well-known engraver.

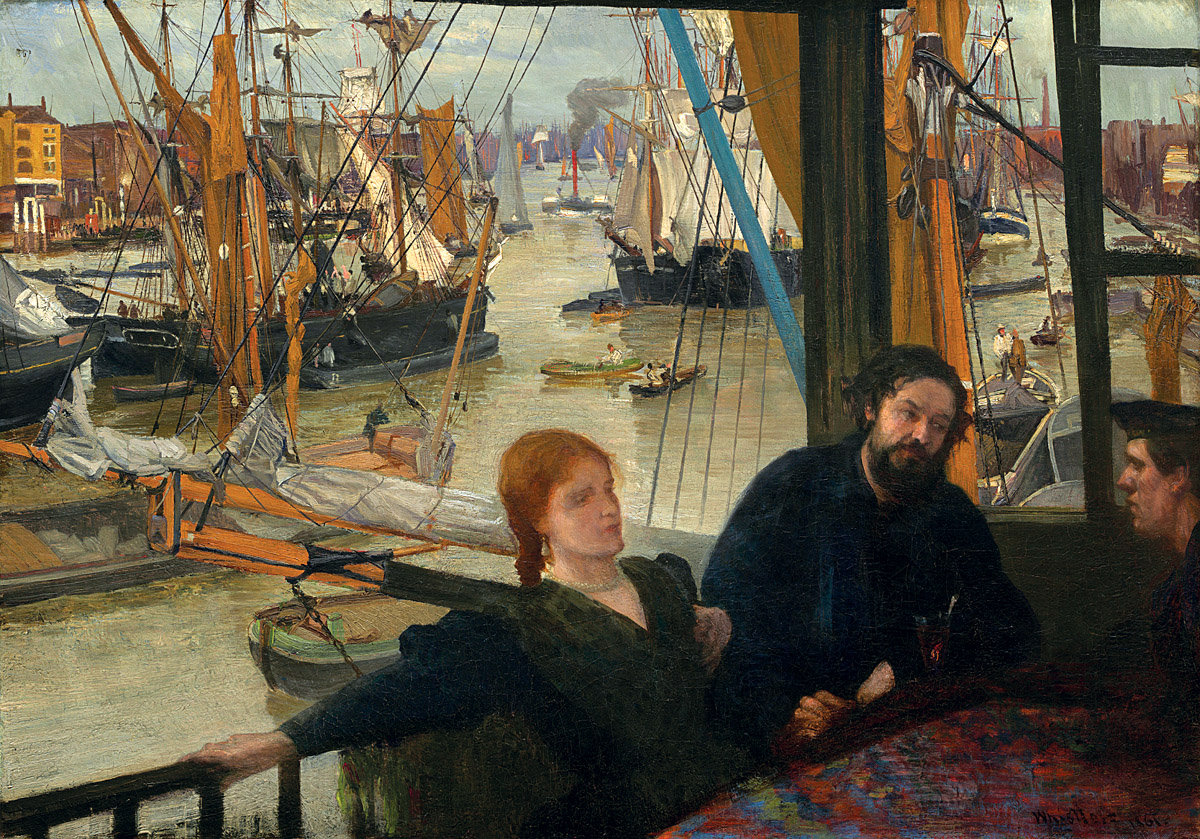

3. Wapping. 1860-1864. 28 x 39 in. (71.1 x 101.6 cm). Signed and dated Whistler 1861. National Gallery of Art, John Hay Whitney Collection, Washington.

In England, the young James enjoyed walking along the shore. He would sit on the sand and make sketches. On November 9, 1849, Major Whistler died without ever seeing his family again, and the repercussions of his demise on the family finances forced them to go back to Connecticut, where they settled at Pomfret. James was now a tall, lanky teenager with a slender figure and a mild expression. He had a vaguely European air which combined with his natural gifts gave him great charm. In short, a delightful youth whom everyone loved. Despite his mother’s strictness, his personality began to show through and his opinions started to take shape. He was a wilful yet helpful youngster, considerate and with a strong sense of humor. He would retain his sense of humor throughout his life, but would frequently hide it behind a serious outward appearance, thus creating a sort of “hot and cold” impression, and a sarcasm which would hurt his victims more than mere jokes.

He continued his studies at a religious academy run by a man with a severe nature who had a puritanical mode of dress. One day, Whistler decided to amuse himself at the expense of this gentleman by turning up in the school playground dressed in a stiff white collar and a tie similar to those worn by the headmaster. His school friends tried to conceal their mirth. The offense was dissimulated behind what passed for homage to the principal, so it was difficult to punish and the victim had to contain his anger. However, he decided to pay special attention to this mocking pupil and took advantage of a subsequent prank to pounce on him, cane in hand. Whistler tried to escape but was unable to avoid a severe caning which caused him more amusement than pain. The Whistlers and the McNeills both had a tradition of military men in the family. James’s mother, despite her awareness of his artistic gifts, fully intended to send him to a military academy to ensure that he had a career worthy of the family name. She thus tried to enroll him at the greatest military academy in the United States, West Point, which he entered in 1851 thanks to the intervention of President Fillmore himself. Even in his first year, his examination results were revealing: he was first in drawing, but thirty-ninth out of forty-three in philosophy and last in chemistry (asked about the nature of silicon, he replied that it was a gas).

One day, in the art class he drew a young French peasant girl. The professor went from table to table examining the work of his students, then returned to his desk to take up the paintbrush and ink with which he was in the habit of correcting their work. As he approached Whistler, the young man saw him coming and raising a hand to ward off the paintbrush, exclaimed, “Please sir, don’t do anything to it, you’ll ruin it.” The teacher smiled understandingly and moved away… James showed his ignorance of history by not knowing the date of the Battle of Buena Vista. “But if you dine with friends,” he was asked, “the conversation might turn to the Mexican War and if someone were to ask you the date, what would you say?” “What would I say?”, replied Whistler, “I would refuse to converse with people who speak of such things at table!” During horseback riding lessons, Whistler was often thrown over his horse’s head. On one such occasion, the major instructing the cadets remarked, “Mr. Whistler, I am happy to see you at the head of the class for once.” His fellow cadets would retain the memory of a young man who was quick-tempered but likable. His short-sighted stare and rumpled hair gave him a neglected air. He was fond of food and often gave in to his gastronomic impulses, which he would satisfy unhesitatingly by sneaking out of school to buy buckwheat cakes, oysters, and club soda. He took little notice of the academy’s discipline and the disapproval of his lateness and his careless dress.

In the three years he spent at West Point, Whistler would decorate his exercise books with caricatures of his fellow cadets, his teachers, and illustrations of the works of Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas or Charles Dickens, evidence of his European background and strong personality. He admired the strictness of the academy’s training, the values which were defended there and the impeccable uniforms. Guided, like his fellows, by a sense of honor, James could not prevent himself from revolting internally against its traditions, despite his respect for certain ideas of chivalry. Like Edgar Allan Poe, his predecessor at West Point, the young man was not cut out for a military career, being incapable of submitting himself to the strict discipline. He was informed of his dismissal in June, 1854. Nevertheless, he remained quite proud of having spent some time at West Point, where one entered as a child and always came out a man. These three years were decisive for his character. The discipline (even if accepted with an ill grace) had forged a moral force which would help him cope with life’s difficulties. He had also learned how to fight there.

Much later, in England, he was always eager to hear news of West Point and showed his attachment to the school when he sent the library a copy of his pamphlet, Whistler v. Ruskin: Art and Art Critics, with the following dedication: “Souvenir of an alumnus who glories in his years at West Point.” After leaving the academy, Whistler was apprenticed at a locomotive factory in Baltimore and spent his days wandering around the workshops and offices. Frederick B. Mehrs, one of his colleagues, recounts that Whistler was in the habit of doodling on his worksheets, which enraged his workmates. One of these drawings, a symbolic one, no doubt, represents a gentleman locked in a dungeon with only a tiny window, everything lit as in a Rembrandt painting. Soon, the boredom became intolerable, and Whistler left Baltimore.

On November 7, 1854, he joined the Geodetic Coastal Survey thanks to an old friend of his father’s, Captain Benham, who was then director of the Survey. Here again, he found he disliked office routine and did his work without enthusiasm. Mapping and the constraints which cartographic drawing imposed soon became as unbearable to the young man as military discipline. Mehrs later recalled that James was often late and that in January he only did six and a half days’ work, while in February he only spent five and three-quarter days in the office. When he was reproached for his tardiness, the young man replied that he deeply regretted it but it was not his fault if the office opened too early. Whistler led a very active social life. He was often to be seen at receptions, dressed in the latest fashion, including a Scotch bonnet.

4. Blue and Silver; Blue Wave, Biarritz. 1862. 24 x 34 in. (62.2 x 86.4 cm). Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Connecticut.

His delicate features bore a tender yet alert expression which belied his impulsive and often violent nature. The young James Whistler was passionate about drawing and painting and despised anything not directly related to it. The maps on which he worked were very laborious, needing to be created meticulously on copper plates. He used any blank space to make sketches. Examples of this can be seen in etchings of his entitled “Outline of a Coast Plate No. 1” and “Outline of a Coast Plate No. 2; the Island of Anacapa.” On the first, one sees two perspectives of rocky coasts. A town is represented in the background. Whistler could not content himself with doing what he was asked to do. Smoke rises from the chimneys, and at the top of the engraving he had sketched profiles of human heads, including an old lady, an Italian wearing an enormous hat and a French soldier. On another plate, there is a flight of birds which from a topographical point of view could not possibly be of importance. Whistler was regarded as something of a practical joker. Benham, the director, was in the habit of touring the workshops to check the work of the engravers, looking at them through their own magnifying glasses.

Whistler had engraved an image of a little demon on his magnifying glass. One can imagine the director’s surprise when, putting the glass to his eye, it revealed a huge mocking devil (Twenty years later, Whistler would be visited by an old man carrying a magnifying glass on a chain who would invite him to look through it… That evening, the two men exchanged happy memories). James became very bored in the Geodetic Coastal Survey and resigned in February, 1855. Yet, as in the case of West Point, the few months he had spent at the office were of great importance for his career. In fact, he had learned how to make etchings, a technique in which he would come to excel.

As soon as Whistler came of age, he decided to go to Paris with an annual allowance of 350 dollars from his family. Since he had learned to speak and write French from an early age, while living in Russia – his conversation and his writings were peppered with French phrases – he had no problem with the language from the moment he arrived in the French capital. Major Whistler’s son was received at the United States legation and in the British pavilion at the Universal Exposition. The artist Gustave Courbet had been refused a place to show his works at the official exhibition and launched his first manifesto on behalf of the Realist School of painting. Whistler became friendly with the artist and thus began a relationship with the Realists. This is how he met Fantin-Latour and Edgar Degas. On November 9, 1855, the young engineer enrolled at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs (School of Applied Arts) in the famous studio of Lecoq de Boisbaudran. He never dreamed of entering the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris’s leading school of art, but like his English friend George du Maurier, he became a pupil of Charles Gleyre in 1856. Gleyre was a well-known teacher of painting, who had inherited the Delaroche studio.

The master welcomed into his studio those who wanted to escape the influence of classes in which the teaching was too classical. They attended Gleyre’s courses, which he gave for free, in parallel with the schools of art, or after classes. Gleyre’s teaching was original, based as it was on personal theories which horrified the academic painters. He recommended preparing color on the palette before beginning to paint.

Whistler adopted this technique, which had the advantage of releasing the painter from constraints, leaving him completely free to work on the modeling. The master also taught that ivory black is the basis of all hues, because when mixed with other colors, it gives very subtle shades. At Gleyre’s workshop, Jimmie Whistler met Edward Poynter, Frederick Leighton, Thomas Armstrong and Alico Ionides, who called themselves the “The Trilby Group” and who would become well-known English painters twenty years later, as well as Rodin, Dalou, Bazire, Regamery, Quentin, Legros…

Whistler became something of a character by walking through the streets with his unusually wide-brimmed straw boater, worn slightly askew. Sometimes he would replace the hat with a soft felt one trimmed with a large black ribbon. The art students led unorthodox lives and were deeply contemptuous of ordinary mortals. The combination of the English and American good manners learned in St. Petersburg and West Point, and “artistic”, eccentric, and sardonic behavior was an explosive mixture. Whistler did not work very hard (one of his projects was to copy, with Tissot, Angélique, the painting by Ingres) and enjoyed himself greatly, sharing a room with Poynter for a while. In a speech to the Royal Academy of Art in 1904, after Whistler’s death, Edward John Poynter declared, “I was very attached to Whistler at first; I knew him very well when he studied in Paris, if working for about eight days a year can be called studying. Before coming through, his genius had to triumph over the laziness and love of pleasure which is the trait common to all art students.”

James moved to a little hotel on the Rue Saint-Sulpice near his friends, the painters Delannoy and Drouet. They would meet in a restaurant in the nearby Rue Dauphine, of which the owner’s son, called Bibi Lalouette, is immortalized in an etching, the only way in which Whistler could pay the debts he had accumulated in this establishment. He would normally rise at 11:30 a.m. or midday, and go out with his sketchpad to make quick sketches of scenes from everyday life. He was feared for his sudden outbursts of anger and several years after he had left, he was still talked about in the neighborhood. He was a favorite among the “bar-girls” of those days. The one he liked best was Héloise, who would recite verses from Alfred de Musset while she was posing and would tear up the artist’s drawings when she was angry. Whistler then took on a calmer model of a completely different type, “Mère Gérard” the old woman who sold flowers and matches at the gate of the Luxembourg Gardens.

Unlike most of his friends, James lived well, but his natural tendency to spend often placed him in difficulty. He once pawned his coat so as to be able to afford an ice cream in a bar on a very hot day. His friends found him walking around in his shirtsleeves. “Well, what can I do, it’s so hot!” Another time, he and his friend Delannoy brought a mattress to the pawnshop but this worthless object was rejected. “That’s fine,” replied Whistler with dignity and deposited the mattress on the ground. “I’ll have it picked up by a messenger boy.” They tried to sell a copy of The Wedding at Cana. Not finding any buyers and irritated at having to keep running around carrying this cumbersome canvas without finding any takers, Whistler had a stroke of genius while passing over the bridge of the Pont des Arts…. The canvas soon took a dive into the Seine. The onlookers sent up a cry of horror, the peace officers came running, ships left the shore. For the two partners-in-crime this was “a fantastic success!”. Whistler also had to pay his cobbler with paintings when the man came to claim what was due to him. When the situation became intolerable, he scrounged money among his American friends.

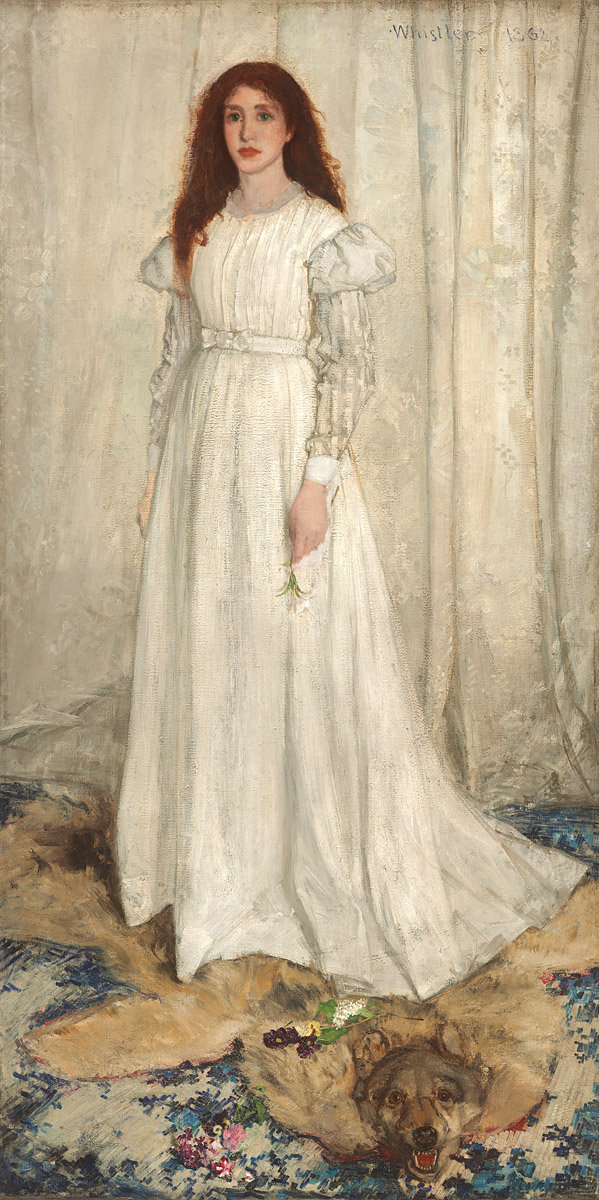

5. Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl. 1862. 86 x 43 in. (214.6 x 108 cm). Harris Whittemore Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

In 1856, Delannoy and Whistler took a trip to Eastern France, traveling to Nancy and Strasbourg, and ending up in Cologne, Germany, where they ran out of money. The innkeeper whose hostelry they were patronizing became impatient at his unpaid bill. As a token of good faith, Whistler decided to leave him some copper plates which he was using for engraving. The trip back to Paris was a painful one and every meal was paid for with a portrait. The friends slept on straw and walked around with holes in the soles of their shoes. On the way, they encountered two travelling musicians who, each time they all arrived in a town, would announce with great ballyhoo that the two artists would paint pictures for a hundred sous. They finally abandoned the musicians in a town in which the U.S. consul, who had known Whistler’s father, lent them enough money to make it home. There remains to us from this trip a series of etchings, including Liverdun, A Street in Saverne, The Kitchen, and Portrait of Gretchen.

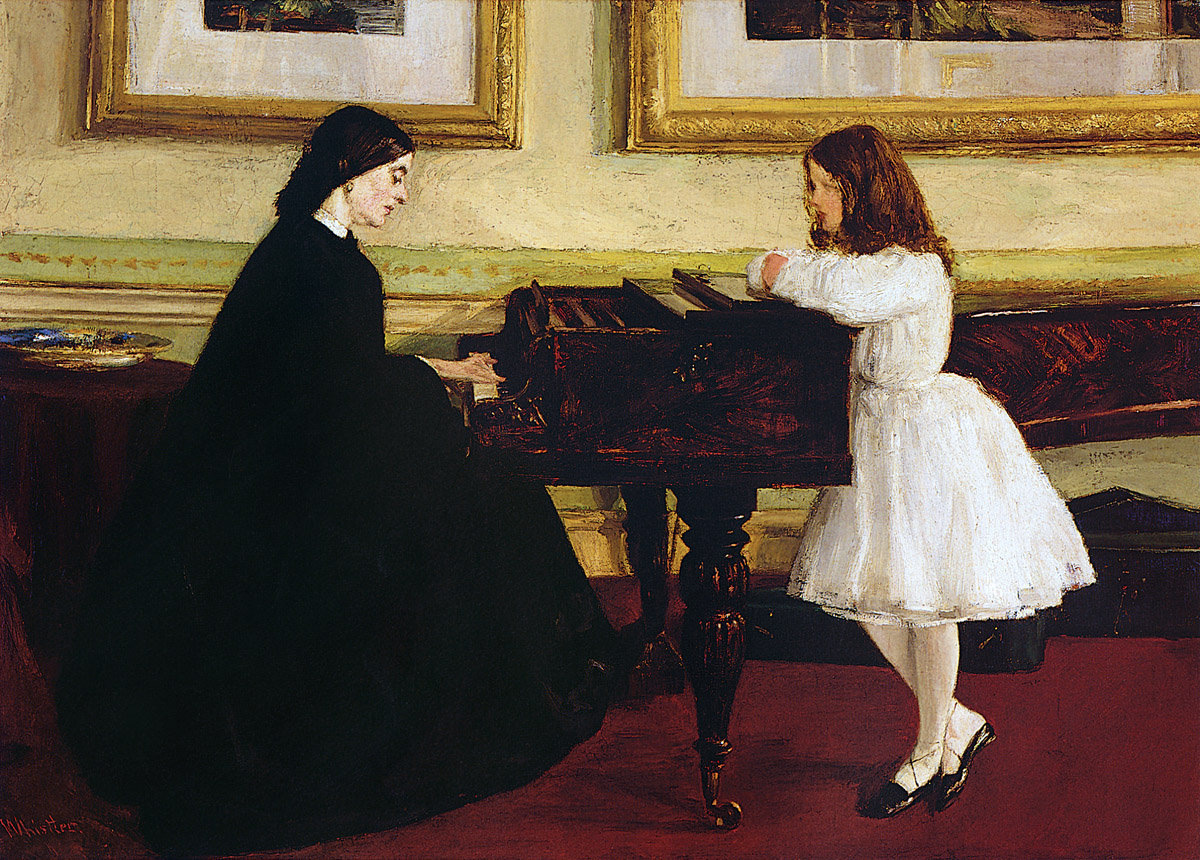

By learning to work from memory on the principles of Lecoq de Boisbaudran, Whistler perfected his technique, especially the effects of light at night-time, working on the basis of one tone, one color, and its variants. He respected the tradition of painting, studied the techniques of the Old Masters and, like his fellow students, went to the Louvre to copy the paintings. He admired Rembrandt and Velasquez. A series of thirteen etchings made in Paris, Alsace, and London, and now known as “The French Set,” was published in a limited edition by the printer-engraver Auguste Delâtre. Whistler made himself personally responsible for the sales. The first paintings he produced were commissions. He made a few copies for Captain Williams of Stonington. His painting At the Piano (which he used to call “The piano picture”) was submitted to the Salon of 1859 but was rejected since it was judged to be too “original.”

This painting revealed an early desire for unity and a harmonious distribution of color. The jury also rejected the paintings of Fantin, Ribot and Legros, causing a scandal. Some of the rejected paintings were exhibited at the Atelier Bonvin, and on this occasion, Whistler was congratulated by Courbet. Fantin-Latour was to paint Whistler five years later in his work called Homage to Delacroix, which featured such promising artists as Manet, Legros, and Braquemont, who surround the poet Baudelaire. In 1865, Fantin sent a second painting to the Salon which also depicted Whistler, this time dressed in a Japanese robe, among a group of artists. He later destroyed this painting, having cut out Whistler’s head in order to turn it into a portrait.

In 1859, Whistler decided to move to London to live with his half-sister, Lady Haden, at 62 Sloane Street. He would never again live in France, although he would visit several times.

Her husband, Seymour Haden, president of the Society of Etchers, bought paintings from his brother-in-law and his brother-in-law’s friends, thus supplying them with valuable financial assistance. For a while Whistler shared a studio with George du Maurier, a cartoonist whose work often appeared in Punch magazine. In the four years between 1859 and 1863, Whistler stopped being a “rebel” and turned into a well-known artist. This did not stop him from playing the fool on Sunday, when he went to visit his friend, Ionides, whose father was a generous philanthropist. He would stand on a chair and sing songs from the Paris dives. Whistler had adopted a very unusual style of dress. People would turn to stare at him as he passed in order to get a good look at this outrageous dandy decked out in a suit of white twill topped with a yellow boater. Sometimes he would carry a parasol, a pink silk handkerchief, and he always wore a monocle and his famous lock of white hair. This lock which stood out from the rest of his black hair, fell across his forehead and was often taken for a feather. A real legend was born, the most farfetched rumors emerged, affirming that it was a birthmark, a sign of his race or even that in reality his hair was white and he dyed all of it but this lock. Whistler considered his white lock as a protection against the devil and looked after it like a precious object. The years 1860 through to 1870 were dominated by his triumph at the British Royal Academy. Whistler submitted At the Piano and five etchings to this institution, which was going through a strong pre-Raphaelite phase. The paintings were accepted and the critics received them quite favorably.

The painter took his first step on the ladder of fame. The artist began a series of eight works on the theme of the River Thames. To complete the project, he lived in a little inn frequented by bargees next to the dock. He would often move to the other bank of the Thames, to Cherry Gardens, where he would sit on the deck of a barge and draw.

He would sometimes be interrupted by the movement of the current, and more than once found himself stuck in the mud. His friends would come and visit him at the inn, among them the lawyer Mr. Thomas, who was wild about painting and patronized the pre-Raphaelites. Thomas decided to publish the series of French etchings as well as the Thames series and gave Whistler the opportunity of using the same method of engraving as used by Rembrandt. In 1859, Whistler produced one of his most beautiful engravings, entitled Rotherhithe. In 1863, the artist worked hard on a canvas which he called Wapping (he started four times on it!). “Hush, don’t tell Courbet,” he begged Fantin in one of his letters. The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1864 and at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1867. It had been painted at the bargees’ inn. It shows three people, a workman, Legros and Jo Heffernan, his model at that time. Courbet, who met her at Trouville, painted her portrait, calling it La Belle Irlandaise (The Beautiful Irish Girl), exhibiting it at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1882 under the title Jo, Femme d’Irlande (Jo, A Woman of Ireland).

Whistler worked on a drypoint entitled Annie Haden, for which the artist’s niece posed wearing a crinoline and a fashionable hat. A society of engravers ordered two etchings to illustrate a book of poems. The work involved was considerable; Whistler claimed to have spent three weeks on each of them. In 1861, he sent La Mère Gérard to the Royal Academy and was acclaimed by the press. In the summer, he sailed to the coast of Brittany in France and painted some realistic landscapes. One of the paintings has an anecdotal title, Alone with the Tide, in the tradition and style of Courbet.

Returning to Paris with Jo Heffernan, Whistler rented a studio on the Boulevard des Batignolles, to paint a life-size full-length portrait of her. She is dressed in white, with a white curtain behind her and a white flower in her hand, her arms are by her sides. The painting is entitled The White Girl. “There is a mysterious charm about the work,” wrote Paul Mantz in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts. The young girl represented looks like a medium or an apparition. The expression on her face and the pose are simple yet disturbing.

In the winter, Whistler fell ill and went down to the Pyrenees. It was thought he might have been poisoned by the zinc white which he used extensively in this painting. While at Guétary, he was saved from drowning by Jo. At Biarritz he painted The Blue Wave, with short, sharp stabs of paintbrush. The painting is very unusual, in that there are no more color gradations, no chiaroscuro, and the composition is simple. Whistler was beginning to disassociate himself from “this damned realism,” as he called it. The Royal Academy refused to exhibit The White Girl, which was judged to be too original, but his etchings were admired and compared to those of Rembrandt. The rejection of The White Girl, which revealed all of Whistler’s originality, says much about the period. The subject disconcerted his contemporaries as well as his treatment of it, with its white on white. The painting was accepted in the same year at the Berners Street Gallery, which gave the public the chance of viewing the work of young painters. “It was a real success of execration,” the painter said at the time. Only the newspaper The Athenaeum emphasized that despite the absence of a “subject” the canvas could under no circumstances be said to be an illustration of the book of the same name by Wilkie Collins.

Whistler was furious and this marked the beginning of his lengthy crusade against the art critics in the press. He protested that he had never intended to illustrate the book which, in any case, he had not even read. He had simply wanted to paint a young girl in white standing in front of a white curtain, that was all there was to it.

Early in his career, Whistler had copied famous paintings in museums, where he constantly encountered the work of Watteau (as well as seeing it at the home of his friend and benefactor, Eseltin). Like Baudelaire, he had a gift for taking existing concepts and bringing them back to life by placing them in a contemporary context. In 1860, Whistler had the same concerns as the French artists who were no longer particularly interested in the art of the early 19th century. The Goncourt family were largely responsible for this situation. They had elevated Watteau, a pleasing artist but no more than that, to the status of the greatest artist of the 18th century. His painting became synonymous with the art of elegance of the Old Regime of the French monarchy.

Under Louis XVIII and the July Monarchy, the deposed aristocracy looked down on the middle classes. The elegance of the 18th century had become a distant dream which they could only recapture in the work of Watteau. His paintings, associated with the Old Regime, were very fashionable from 1830 through 1880. The diminutive figures lost in huge gardens influenced Whistler considerably and he attempted to convey the same poetic vision and musical analogy as his predecessor. An elitist, though a bohemian, he tried to serve as a mirror for the aristocracy and side with them in their liberation from bourgeois convention. Although Whistler had posed his model slightly in profile in the painting The White Girl, the shoulders are in exactly the same position as in the model who posed for Watteau’s painting entitled Gilles and the hands are in the same position. Jo’s hair surrounds her face like a dark halo just as the round hat in Gilles throws a dark shadow on the model’s face. The details of the white yoke are an echo of the vertical embroidery on the clothing in Gilles. Whistler changed the decor, moving it from a theater stage to the interior of his studio, but retained the general look of the painting. Instead of an androgynous character, he presents us with an elegant woman. The trees which surrounded Gilles are reduced to patterns on the Victorian curtains. Whistler turned the donkey’s head into a bearskin rug, but he has taken the idea of white-on-white further than did Watteau. Despite the removal of any anecdotal detail, the ambiguous and melancholy presence conveyed by the two subjects is very similar. Paul Mantz understood this in 1863, when he wrote, “If we dare to claim that Whistler is an eccentric when on the contrary he has a whole past and tradition which we ought not to ignore, especially we in France, we would appear to be very ignorant of the history of Art. Whistler must have known that Jean-Baptiste Oudry has sought to group different white objects together and that at the Salon in 1753 he exhibited a large painting depicting various white objects against a white background, including a duck, a damask table napkin, porcelain, and a creamer …all of them white.” On the subject of Watteau’s paintings, the Goncourts had written, “It is love, but a love that dreams and thinks. Modern love with its aspirations and its crown of melancholy.” The individuals depicted in The White Girl and Gilles are both pursuing their dreams. At that period, the Cremorne Gardens, where Whistler spent a lot of his time, held performances featuring pierrots. Whistler reproduced this theme and the erotic connotations of the painting are directed toward Gavarni’s depictions of Pierrot. He copied a Gavarni lithograph entitled Airs: Larifla or Two Clowns Dancing. Clowns were popular in the 19th century and people often attended masquerades dressed as clowns where they could engage in brief affairs in semi-anonymity.

6. Purple and Rose: The Lange Lijzen of the Six Marks. 1864. 35 7/8 x 22 1/8 in. (91 x 56 cm). The John G. Johnson Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

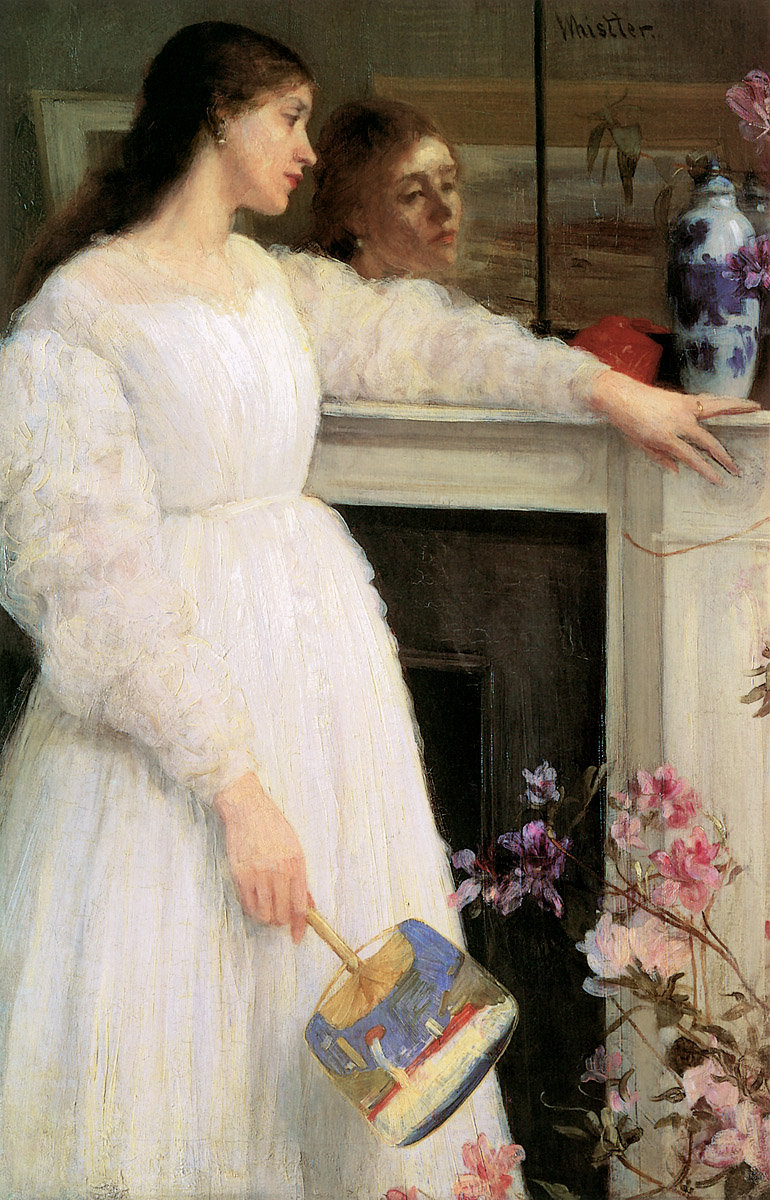

7. Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl. 1864. 29 7/8 x 20 in. (76 x 51 cm). Tate Gallery, London.

All the great themes beloved by Whistler are present in The White Girl – the purified shapes, the play of colors, tone upon tone. In 1856, the Goncourt brothers were asking themselves, “Which school do Watteau’s paintings belong to? They are painted with an originality of color that is unprecedented. In Watteau, the fantasy of color seems to have an additional dimension.” In 1884, a fashion magazine stated that “women are particularly fond of Watteau because he created ‘a style’ for them. He is the magician who taught them to be beautiful, his name remains synonymous with exquisite elegance and graceful purity.” It is this same purity which Whistler seeks in his paintings; the hats, dresses, buttons, and all the fashion accessories bear the Watteau stamp. Whistler paid great attention to the accessories and clothing chosen by his models when he painted them. He never hesitated to insist on a particular accessory or a particular color and was certainly well aware of the importance of clothing in Watteau’s work.

The etchings were soon shown in Paris. The poet Baudelaire admired them, demonstrating his perspicacity. This is what he wrote about the engravings, “A young American artist, Mr. Whistler, exhibited a series of etchings at the Martinet Gallery, improvised and inspired, representing the banks of the Thames and brilliantly executed, packed with rigging, sails and ropes; a chaos of mists, furnaces and uncorked smoke; the profound and complicated poetry of a vast capital city.” In the course of that summer, Whistler made the acquaintance of Rossetti and did six drawings for illustrated publications. Four of them appeared in Once a Week and two others in Good Works. He also completed an important painting, Old Westminster Bridge, which he sent to the Royal Academy in 1863, with six engravings. Despite his London disappointment with The White Girl, he decided to exhibit it in Paris. Unfortunately, that year the Salon rejected a whole generation of painters, including Manet and Whistler. Napoleon III decided to inaugurate a Salon des Refusés, which was held at the Palace of Industry, the same place as the official Salon. The opening on May 16, 1863 owed much of its success to the scandal which preceded its announcement. The public and the critics visited the Salon des Refusés to have a good time. Fernand Desnoyers wrote that Whistler’s painting was the portrait of a medium and claimed that the artist was “the most spiritualist of the painters,” adding that his portrait was the most remarkable. The public hesitated for a moment, shocked out of their normal habits but confusedly sensitive to the simplicity and strange beauty of the work. Later, Whistler would re-christen the portrait Symphony in White. The painting was the event of the exhibition, becoming even more notorious than Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (which at the time was called Le Bain (The Bath)). At the time of the exhibition, Whistler was in Amsterdam with Legros to look at the Rembrandts. It was here that he learned that his painting was causing a sensation in Paris. Fantin wrote to him, “Courbet is calling your painting an apparition and Baudelaire finds it charming… We all think that it is admirable.” After the Parisian triumph came new honors from England and Holland. The etchings exhibited at The Hague won him a gold medal, the first in his career, and the British Museum bought twelve of his engravings. Whistler decided to return to London. His mother came to join him, after having experienced a difficult time: she and her son William, a doctor in the Confederate Army, had been in Richmond throughout the siege of that city.

By the end of this period, James had acquired a reputation thanks to his works on classical lines but totally modern in their style. His paintings were not devoted to particular themes, and Whistler seemed to be totally original but he had won the admiration of his fellow artists and of connaisseurs.