THE EVOLUTION OF THE AMBASSADORS

Jean de Dinteville (1504–55), who commissioned the work, went to London in February 1533 as France’s ambassador and stayed for nine months. In a letter dated May 23 to his brother François de Dinteville, the Bishop of Auxerre, Jean talks about an unofficial visit paid by his friend Georges de Selve (1509–42), the Bishop of Lavaur: “Monsignor de Lavaur did me the honour of paying me a visit, which delighted me. But it is not absolutely necessary for the Grand Master [Montmorency] to find out about that.”[1]

Far from being kept secret, however, the meeting of the two friends in London was to be immortalized in one of the most celebrated portraits of all time.[2]

The year of the picture, moreover, coincides with a turning point in the history of England: the divorce of Henry VIII from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, which gave rise to the schism between the Anglican and the Roman Catholic Church. Indeed, the Cosmati pavement in the picture is borrowed from the mosaic in the sanctuary of Westminster Abbey, which sets the double portrait in the context of the ensuing religious conflict, while the indication of the exact date renders the painted subjets witnesses to this critical moment in history.

Two protagonists

The two protagonists are Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve. Against this highly complex historical backgroud, Jean de Dinteville, while sojourning in England, commissioned Holbein to portray the two friends. Holbein, who had spent another four years in Basle, had returned to a wholly altered situation in London: Sir Thomas More, who had been his host and procured a number of portrait commissions for him during his first stay in London, had fallen out of favour with the royal court because of his opposition to Henry VIII’s divorce. Holbein, on the other hand, festively decorated the Steelyard for the procession attending Anne Boleyn’s coronation on 31 May 1533.[3] In view of Holbein’s allegiance to the Crown, Erasmus wrote a letter that same year complaining that Holbein had disappointed his friends in London.[4]

There is no documentation whatsoever regarding the association between Holbein and Jean de Dinteville. However, the middle-man may well have been Nicolas Bourbon, the court poet, an exile from France. Bourbon had lived in the circles of Margaret of Navarre before being invited to the English court by Anne Boleyn, his patroness. Bourbon’s book of poetry Nugae includes a poem on the art of Holbein[5] as well as an epigram on the Seigneur de Polisy: “In gratiam Ioan. Dintauilli Polysi, cum Christianis. Regis orator in Britannia ageret ... Temporibus cede, et uentis ne flantibus obsta. In domo clariss. Uirir D. Ioan. Dintauillae, quae uulgo etiam, orator appellatur.”[6] The picture of The Ambassadors was kept in the Dinteville family palace in the French town of Polisy (Troyes), but the palace was completely redesigned in 1544; consequently, there is no concrete evidence as to the painting’s intended destination, nor has any document yet been found that would permit reconstruction of the painting’s immediate surroundings. The format as well as the life-sized scale of the picture, however, predetermine the manner in which it should be hanged.

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533. Details (portraits of Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve)

Three different points of view

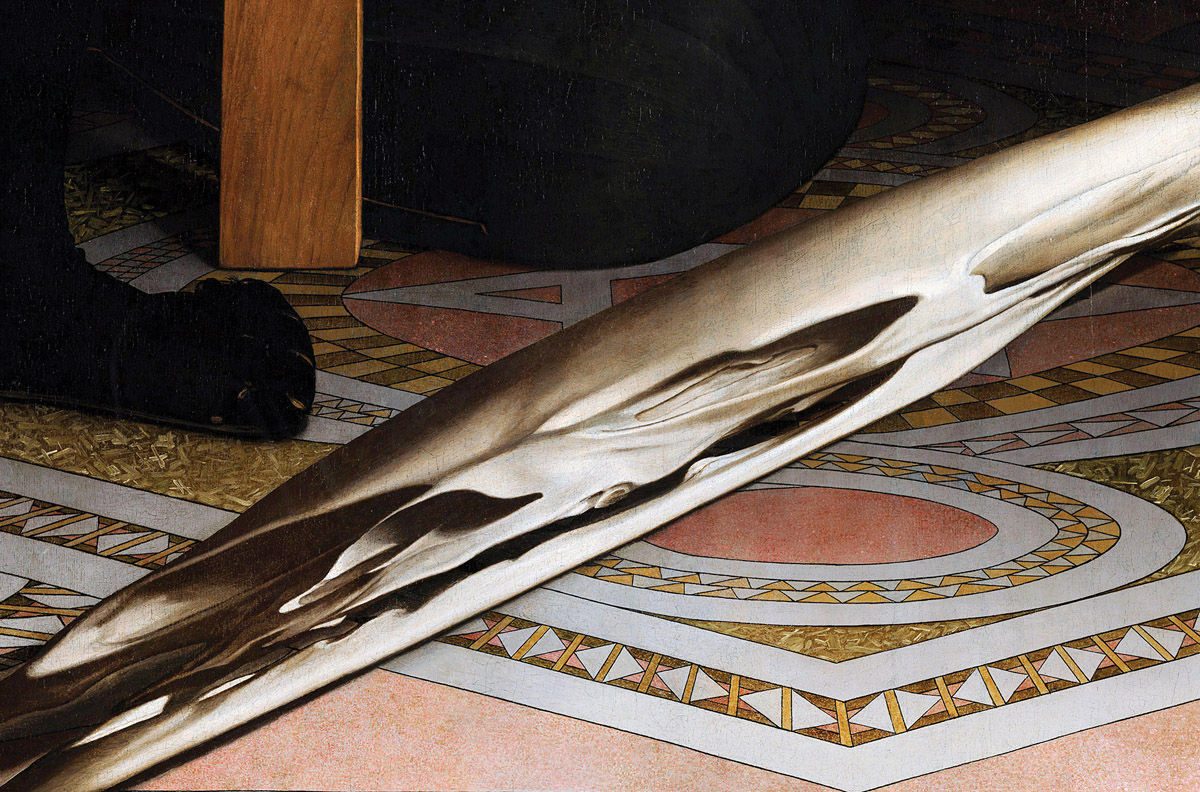

The perspective in The Ambassadors presents three different viewpoints, passing virtually seamlessly from a distant view to close-up and diagonal view. The pictorial reality alone makes it possible for these mutually exclusive perspectives to coexist. The overall effect of the picture is dominated by the imposing life-sized appearance of the two men, whose posture and gaze confront the viewer en face. The rich details of the still life elements and the crucifix above Jean de Dinteville in the upper left-hand corner need to be viewed close up. The anamorphosis, on the other hand, straightens out when the viewer relinquishes his head-on position and stands next to the picture at an angle,[7] to the right of Georges de Selve as it were, his head at the level of the crucifix.[8] Thus, the viewer becomes, in a manner of speaking, the third protagonist. The vantage point from which the viewer regards the skull is in the extension of a diagonal axis generated by the anamorphosis, to the right of the picture.

From two-dimensional canvas to three-dimensional effect

To examine the two perspectives—frontal and lateral—let us begin with a description of the geometrical construction of the linear perspective. However, the idea is not to simulate the artist’s reality and reconstruct the space and objects depicted, i.e. “what the artist was able to see,”[9] but to gain a better understanding of the painting and its structure.

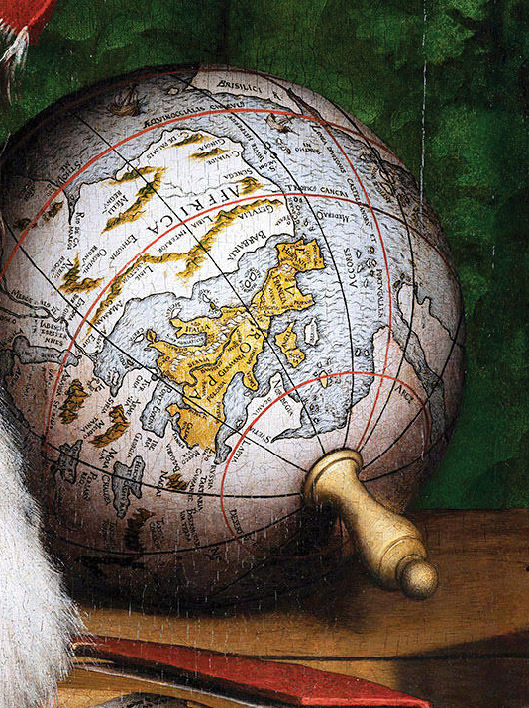

Specifically, the two-dimensionality of the surface of this picture, particularly that of the anamorphosis, is deliberately contrasted with the three-dimensionality of the space depicted. The illusion of depth is created by foreshortening the square pattern on the floor to a rhombus. The starting point of the middle perspective verticals is the apex of that rhombus in the foreground, which combines with the outermost lines of the rhombus to foreshorten the perspective. The vanishing point is on the celestial globe, whose equator coincides with the horizon line.[10]

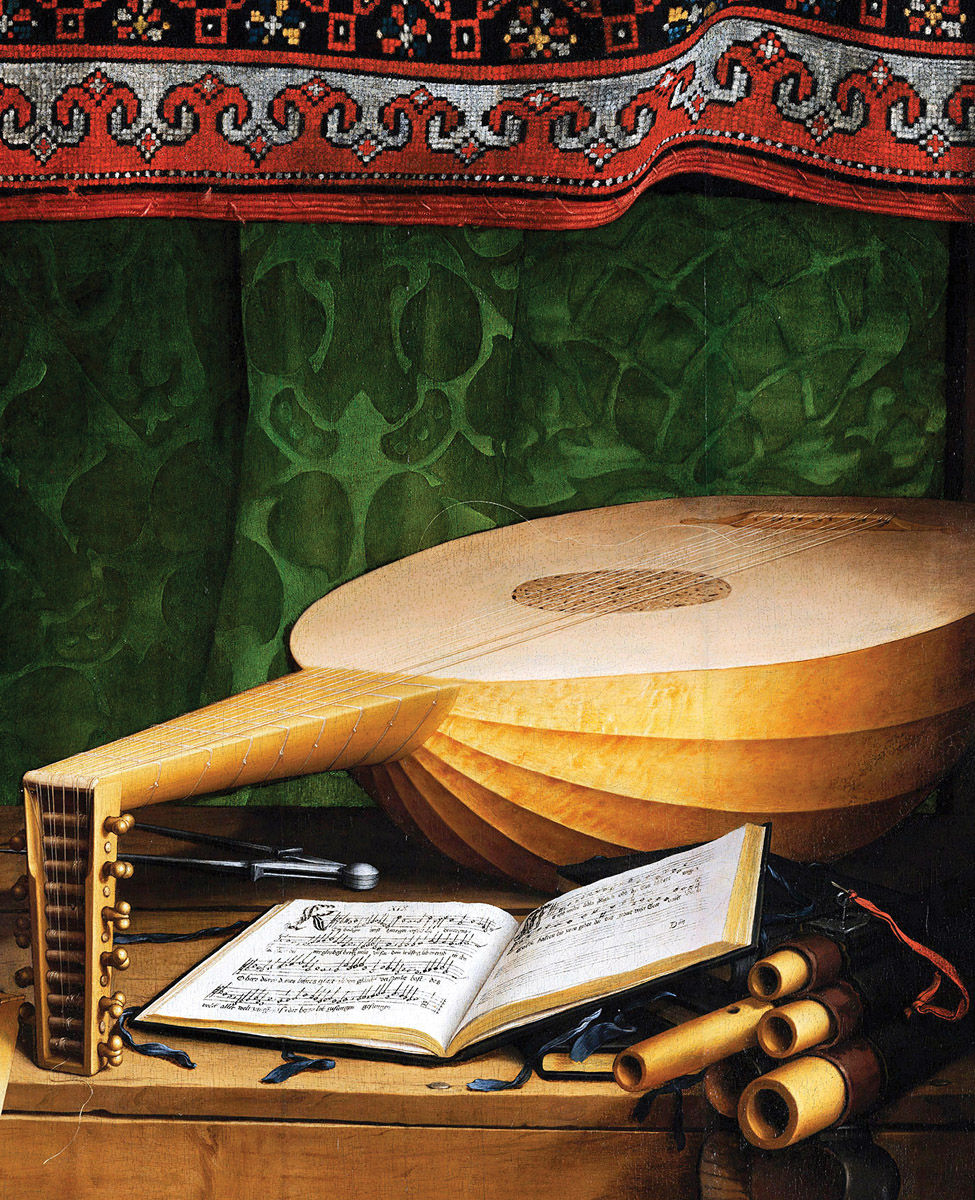

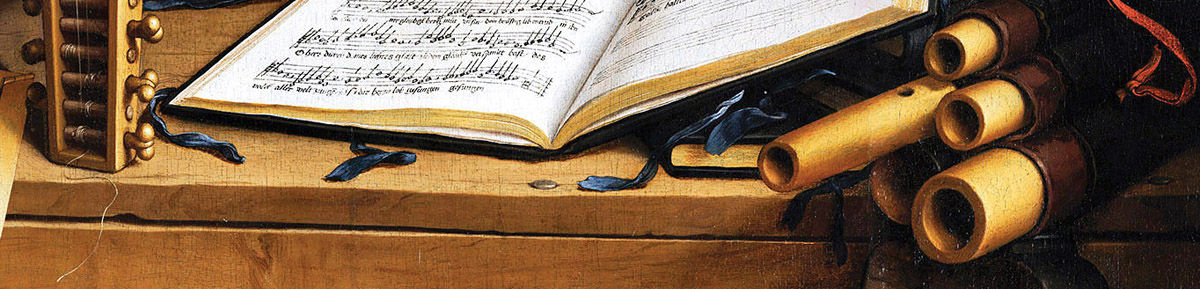

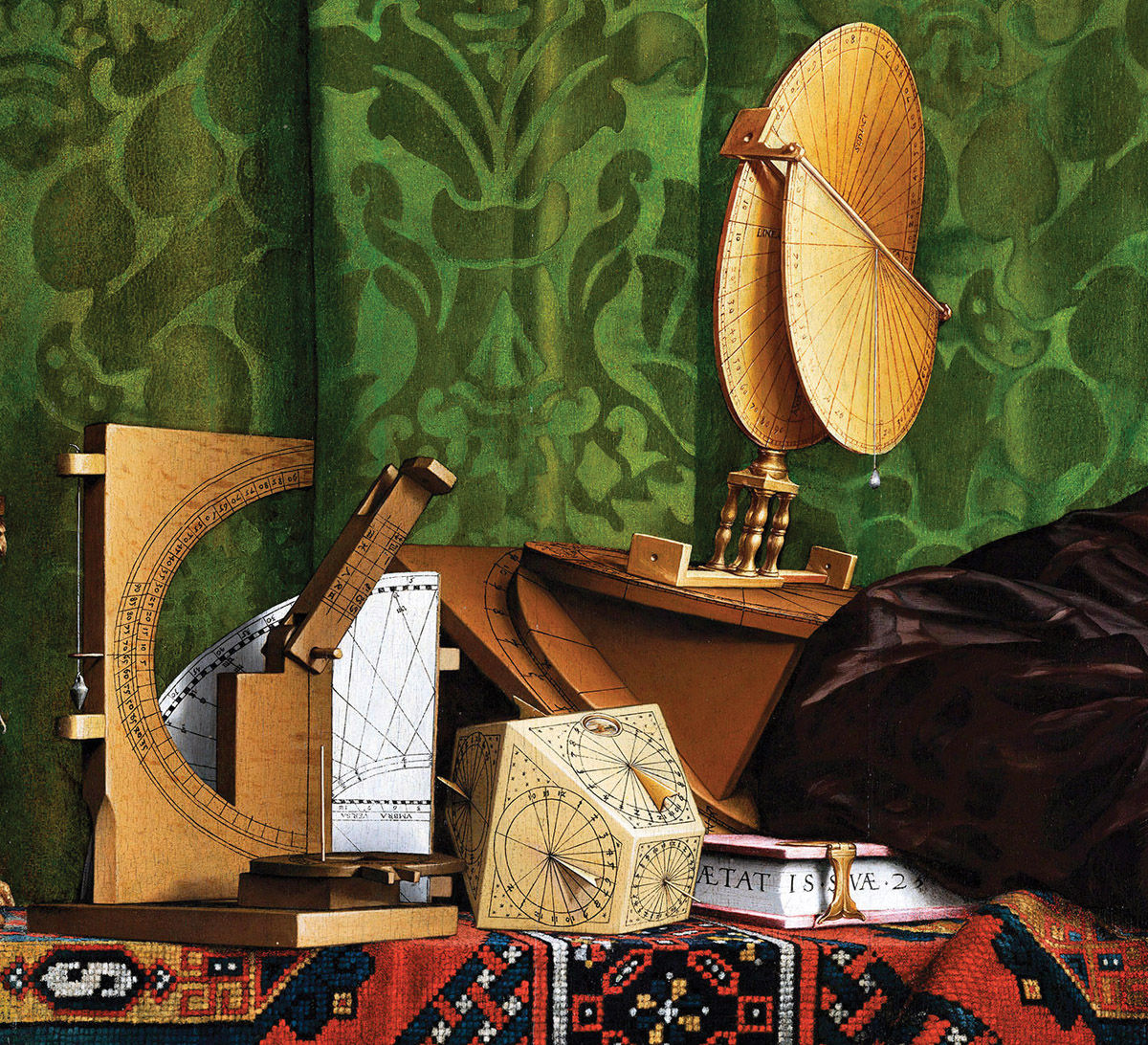

But the horizon line is below eye-level. The foreshortening of the two horizontal wooden shelves in the middle of the picture yields a view from above.[11] Furthermore, the oriental rug on the upper shelf has the effect of dislocating the instruments and objects on top of it from the ambient spatial perspective: the astronomical instruments, ranging from the foldout/collapsible torquetum to the octagonal sundial, are interlocked in a quasi-cubistic manner and seem to drift away from the ambient space created by the centralized perspective. They are isolated from the picture as a whole, constituting an entirely separate pictorial level.

Another field of vision is engendered by the lines of the prayer book on the lower shelf, which intersect with the rosette of the lute. A separate complex of angles is formed by the apex of the set square, the wooden handle of the globe and the pegbox of the lute.

But how is the anamorphosis incorporated into the picture? Two sources of light serve to underscore the separation of the different pictorial areas.[12] The shadow of Jean de Dinteville on the floor and the shadows of the lute and recorders are cast by light shining frontally from above on the right-hand side. The shadow cast by the anamorphosis, however, suggests a second light source, situated at an acute angle to the surface of the picture in the extension of the axis of the anamorphosis to the right of the picture. The shadows place the two men and the objects in the illusory pictorial space, which is lent a level of reality by the plasticity created by the lighting. By dint of its elliptical shape, the anamorphosis to the fore appears to be suspended weightlessly. Only the shadow it casts anchors it as an object in space.[13] Its shadow detaches it from the surface and assigns it a background function. The upshot is a dialectic between the object and its shadow. The shadow places the intangible shape of the anamorphosis as a tangible object in three-dimensional space, thus giving it a temporal and spatial dimension.