Plates

1. Master E. S. (fl. c. 1450–1467), The Virgin and Child on a Grassy Bench between St. Barbara and St. Dorothy. C. 1450. Engraving. 142 x 102 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count; Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. No. 149672; Lehrs 75; Geisberg, Die Anfänge, p. 82

The Virgin and Child on a Grassy Bench between St. Barbara and St. Dorothy belongs to the artist’s early period, the beginning of the 1450s. The print was repeatedly copied in the fifteenth century, and was even reproduced in oils. Its popularity seems chiefly due to the choice of subject which contemporaries found very appealing. St. Barbara and St. Dorothy were both martyred virgins who suffered death by beheading for remaining true to their Christian faith. They are shown standing on either side of Mary, who is seated upon a grassy bench cut from turf and enclosed by planks, which is symbolic of her purity. By representing the Virgin Mother of God with two virgin saints, the artist sought to extol Christian martyrdom and to honor the cult of virginity, greatly venerated in those days.

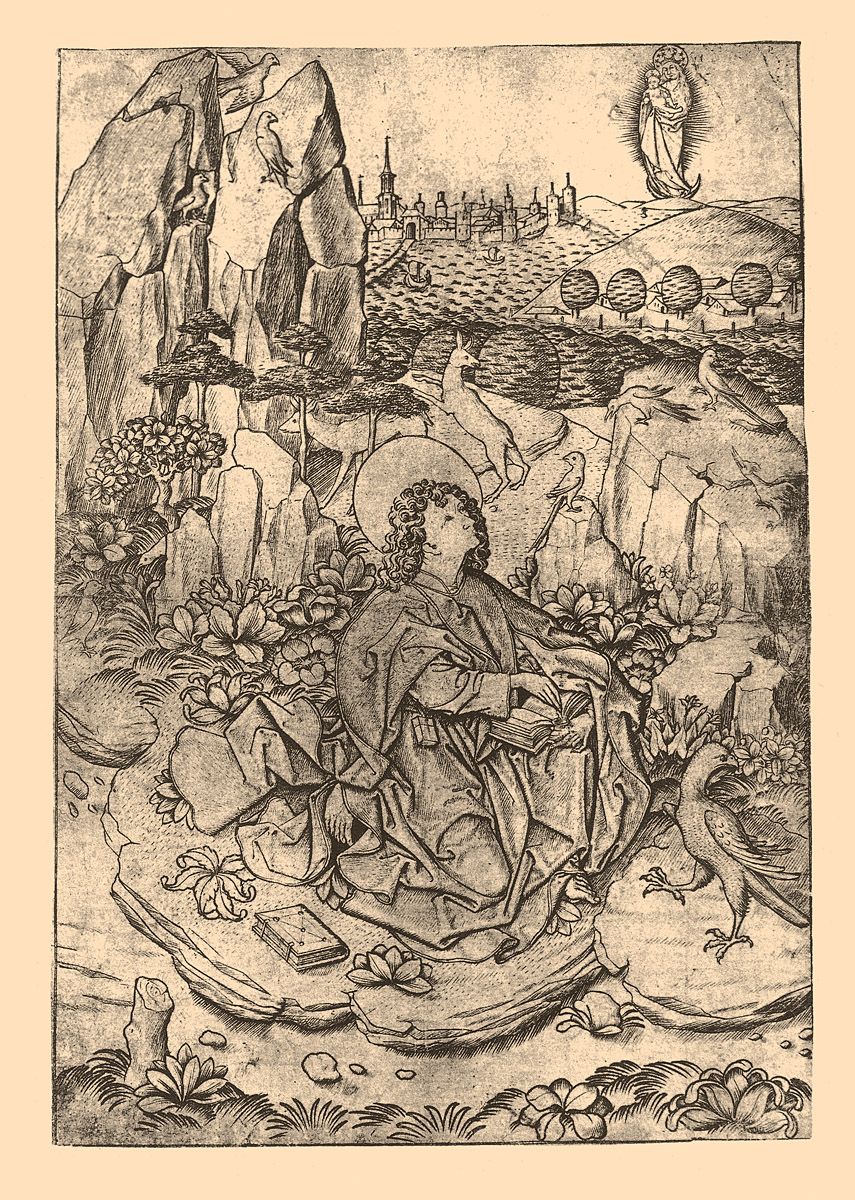

2. Master E. S. (fl. c. 1450–1467), St. John on Patmos. C. 1460. Engraving. 205 x 142 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. No. 149673; Zanetti, 2; Lehrs 151; Geisberg, Die Anfänge, p. 100; Master E. S. Exhibition 33

St. John on Patmos (L. 151) is one of the best surviving prints by this artist. It is notable in particular for the rare perfection of its rendering of plant and animal motifs, which are in no way inferior in precision and vividness to the master’s best works in this field, such as his pictures of animals on playing cards. Though in fact belonging to Master E. S.’s middle period, the engraving bears marks of deliberate archaization: to imitate the effects of earlier prints, the artist rejects the method of cross-hatching which he had already employed in some of his works, and confines himself to the techniques used by his predecessors at a time when engraving on metal was still in its infancy.

3. Master E. S. (fl. c. 1450–1467), The Queen of Shields. C. 1463. From The Small Set of Playing Cards. Engraving. 100 x 70 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count; Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. No. 151380; Passavant 206; Lehrs 235/I

As regards its technical aspect, The Queen of Shields (L. 235) is typical of the master’s productions of the early 1460s, in that it shows the use of punches, and a deeply cut outline combined with very light hatching. Only a strictly limited number of good impressions could be taken from a plate prepared in this manner. Soon after Master E. S.’s death, the plate had to be reworked; this was done by Israhel van Meckenem. Apart from the Hermitage sheet, there is only one other surviving impression of The Queen of Shields printed from the author’s plate in its original state.

In spite of a certain rigidity of attitude, the figures of Master E. S. are not devoid of grace and charm. His work stands out from the highly expressive German engraving of the period as a lyrical version of Late Gothic, tinged with a mood of gentle melancholy.

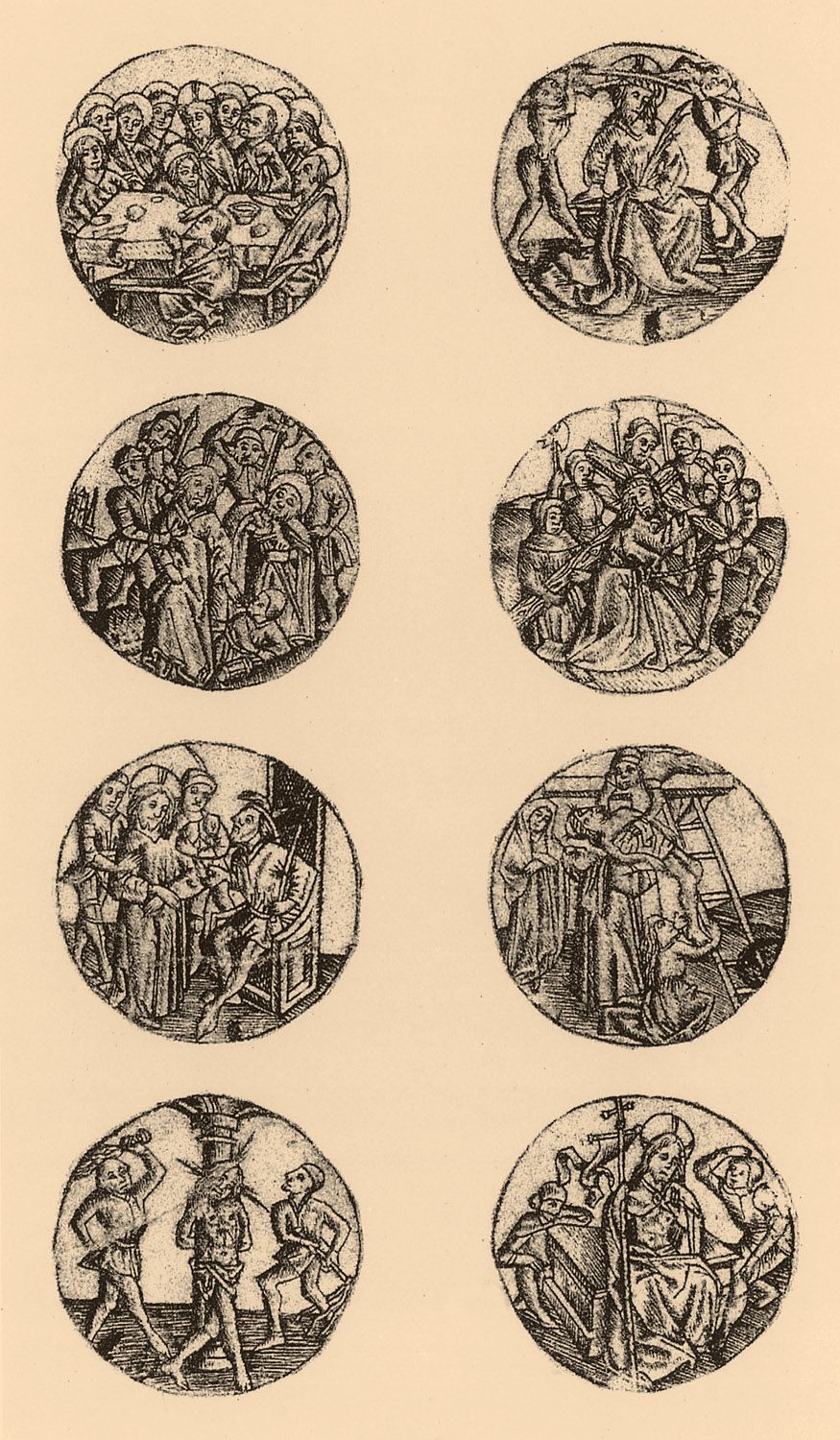

4. Anonymous German Master of the Fifteenth Century, The Passion Series: Sheets 1–8.C. 1470–80. Reversed copy after an engraving by Master E. S. (Lehrs 201). Engraving. Diameter 26 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count; Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. Nos. 151369–151376; Undescribed, unique

The style of Master E. S. was influenced by that of the sculptor Nicolaus Gerhaert van Leyden, who introduced into the plastic art of Germany the dynamic effect of draperies. Paintings by Rogier van der Weyden and his followers, as well as pre-Eyckian miniatures of the Franco-Flemish school, also had a share in the formation of his style. In his turn, Master E. S. exerted a strong influence on the art of the period. This is attested to by the existence of a large number of copies of his prints, not only of German but also of Netherlandish and Italian production. Certain plastic motifs originating with him came to be widely used in sculpture and the applied arts. The series of roundels engraved with the subjects of The Passion (L.) in the Hermitage collection, published in our book – supposedly, the only surviving copy of a sheet (L. 201) by Master E. S. dating from the 1470s – is further evidence of his exceptional popularity with the public of his day.

Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491) was the first of the German engravers who deserves to be called a genius. His oeuvre is more completely represented in the Hermitage collection than the work of Master E. S. Included in this volume are several of Schongauer’s prints, dating from different periods and giving a general idea of the evolution of his style.

5. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), Christ as a Man of Sorrows between the Virgin Mary and St. John. C. 1471–73. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 200 x 158 mm. Watermark: Gothic p with staff and flower. Provenance: Academy of Fine Arts, 1931; Inv. No. 272042; Bartsch 66/II; Lehrs 34/II

Christ as a Man of Sorrows between the Virgin Mary and St. John (L. 34), created between c. 1471 and 1473, is probably the earliest of all known prints by Schongauer. As was often the case in Netherlandish art, a mystical scene is set here within architectural framing, as if seen through a church window: an allusion to the idea that the temple is the House of God.

6. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), The Adoration of the Magi. C. 1470–75. II for The Life of the Virgin series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 252 x 170 mm (cut). Watermark: Gothic p with flower. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154664; Bartsch 6; Lehrs 6/II; Shestack 39

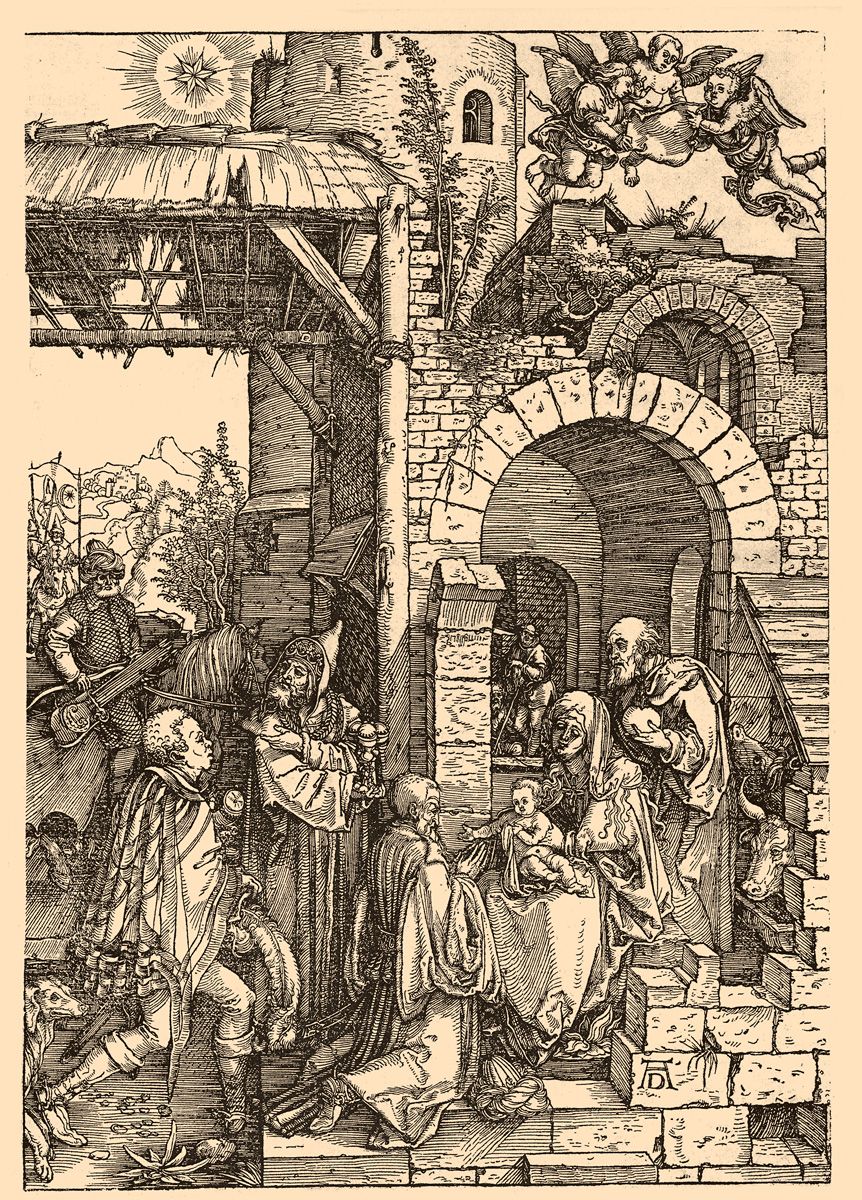

The Adoration of the Magi (L. 6) and The Flight into Egypt (L. 7) for The Life of the Virgin series (L. 5-8), executed between c. 1470 and 1475 – two other early works by this master – are also marked by strong Netherlandish influence. Certain compositional elements of the former recall the works of Rogier van der Weyden, Hugo van der Goes and Dirck Bouts: we find here similar types, a great number of figures, and a distant landscape presented as if seen from an elevated viewpoint. But his impressions of Flemish art are transformed by the master’s individual temperament; and the drawing is marked by a purely Schongauerian vigor. Some parts of the landscape background in this work, as well as in his famous Peasant Family Going to Market (L. 90), reveal an essentially novel attitude: they are based on direct observation of nature, and had probably even been recorded in sketches from life in which the engraver came close to understanding linear and aerial perspective. Innovations are used side by side with traditional devices; thus, the outlines of the barren crags vary the old scheme common enough in the devotional pictures of the time.

Schongauer had a brilliant gift of composition. In The Adoration of the Magi (L. 6), his manner of presenting distance is calculated to convey an idea of the great length of the Magi’s journey. The procession of the travelers from afar is seen at a moment when, having made its way around the foot of the bare and impassable mountain range, it is moving straight forward in the direction of the spectator. The riders in Oriental costumes towering above the crowd render the walkers insignificant or screen them from sight, so that only some heads are left visible here and there, to give an impression that the train is endless, extending, as it were, into infinity. This compositional device was employed by Dürer in his woodcut of the same title (B. 87) executed c. 1504.

7. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), Peasant Family Going to Market. C. 1470–75. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 160 x 163 mm. Watermark: Triple mountain with clover leaf. Provenance: Johann Peter Maria Cerroni (Lugt 1432); before 1830; Inv. No. 276679; Bartsch 88; Lehrs 90; Shestack 34

8. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), The Flight into Egypt. C. 1470–75. III for The Life of the Virgin series. Signed in monogram; Engraving. 252 x 169 mm. Provenance: Johann Peter Maria Cerroni (Lugt 1432); acquired before 1830; Inv. No. 143804; Bartsch 7; Lehrs 7; Shestack 40

The Flight into Egypt (L. 7) is one of Schongauer’s masterpieces. His rendering of details is strictly lifelike and accurate; yet he uses, at the same time, the language of allegory: each of the objects has been chosen not because it just happened to meet the artist’s eye, but because it has a certain symbolic significance, and may serve as a key to some religious or poetic concept.

Schongauer’s interpretation of the story shows that he was familiar with the apocryphal Gospel known as Historia de Nativitate Mariae et Infantia Salvatoris (XX) dealing with the infancy of Christ and the miracles of that period. Following this source, the artist depicts the palm trees which grew up in the barren wilderness in answer to the prayers of the Christ Child, so as to shelter the wayfarers from the scorching rays of the sun, and to give them sustenance.

Standing on the left is the Dragon-Tree, associated, in the beliefs of the time, with the Tree of Eternal Life which once grew in Paradise. According to a Spanish legend elaborating the narrative of the apocryphal Historia, during the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt, evil spirits in the form of dragons entered the Tree to compel men to worship them; but on the approach of Christ they were cast out, and the Tree bowed before Christ in gratitude.

On the trunk of the Tree and at its foot, Schongauer represents several lizards. These creatures were traditionally identified with dragons: for instance, on the left wing of Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych Earthly Paradise, (or The Garden of Earthly Delights, Prado, Madrid), there is a depiction of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil with the serpent twisted ’round its trunk, and satanic salamanders below which resemble the lizards in Schongauer’s print. These moist and scaleless creatures, crawling on their bellies, were regarded as identical with the dragon; this detail in his print shows that Schongauer was illustrating not only the famous apocryphal Gospel, but also the accompanying legend depicting the defeat of the forces of evil who fled before Christ’s holy presence.

The Historia de Nativitate Mariae et Infantia Salvatoris tells how, during their flight into Egypt, the Holy Family were attended by friendly animals. Schongauer’s landscape includes several animal figures, also invested with allegorical meanings and, in a way, expressive of the pantheistic tendency inherent in medieval Christian mythology. The stag, a symbol of Christian thirst and zeal for God, was one of the principal emblems of Christ, as ancient as the fish and the lamb. The parrot, which signified benevolence and beneficence, was an emblem of the Virgin Mary.

Schongauer’s interpretation of the story of the Flight into Egypt was at a later date followed by Dürer who, dealing with the same subject in his woodcut of 1504, illustrated the same source in even greater detail; for he presented not only the palm-trees, the Dragon-Tree, and the lizard devils in flight, but also the brook which, according to the apocryphal Gospel, sprang from the ground before the Holy Family. It is significant that Dürer’s composition also includes the ox, a symbol of the future sacrificial death of Christ, and a plank enclosure, a symbol of Mary’s virginity, and of the Christ-child’s divine origin.

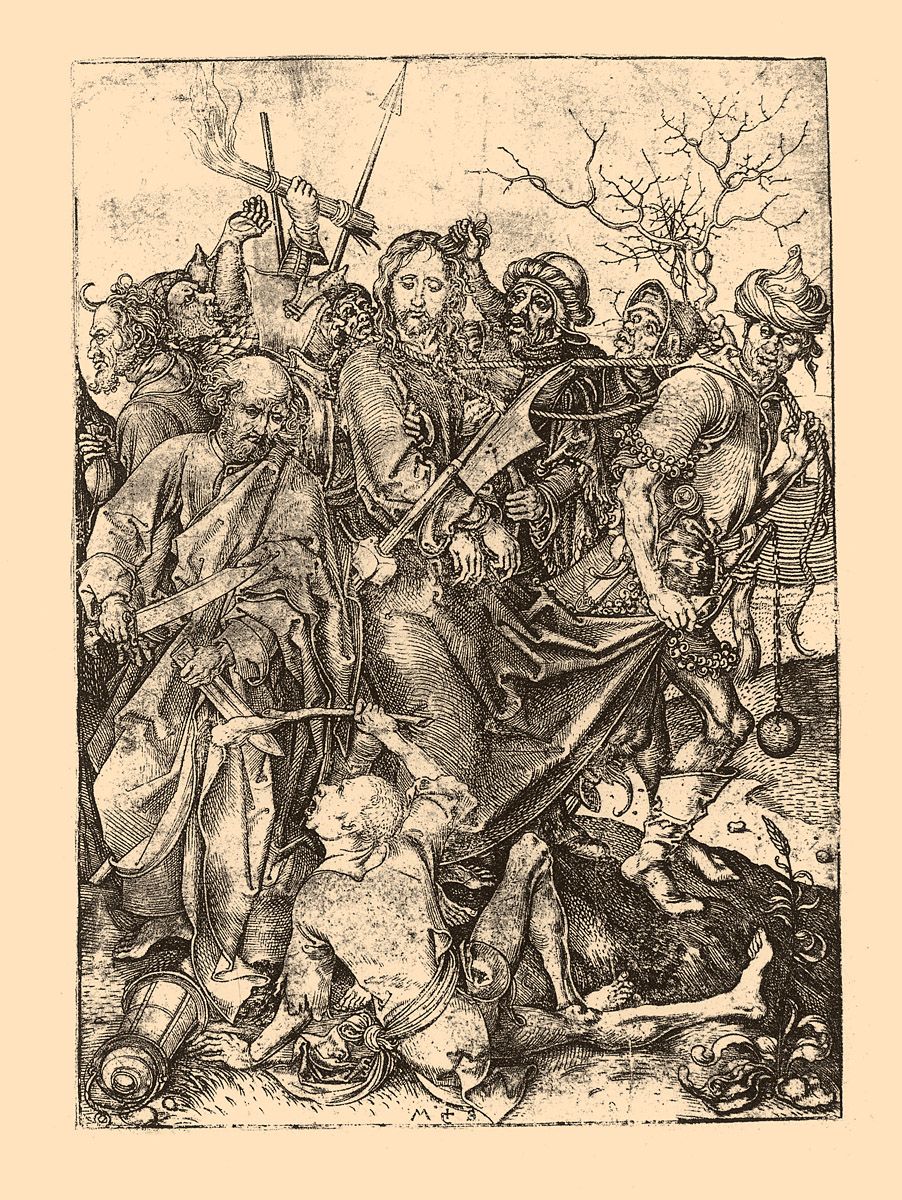

9. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), The Betrayal and Capture of Christ. C. 1480. II from The Passion series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 163 x 117 mm. Watermark: Gothic p with flower. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154662; Bartsch 10; Lehrs 20; Shestack 52

In his Passion series (L. 19–30) of c. 1480, one of the prints from which, The Betrayal and Capture of Christ (L. 20), is to be found in this volume, Schongauer is somewhat less dependent than previously on the Netherlandish style with its characteristic interest in the representation of infinite space. As compared with The Life of the Virgin series where the composition tends to develop into the depth of the sheet, The Passion set is distinguished by a tendency to arrange the figures in a kind of frieze. Here the artist may be said to have followed the tradition of expressive realism as exemplified in the art of his German predecessors, Hans Multscher and the Master of the Karlsruhe Passion. The influence of this tradition is also felt in the heightened drama and nervous intensity of his composition. Schongauer’s familiarity with the work of the German engravers of the older generation, such as the Master of the Berlin Passion, or Master E. S., is also manifested in his ordering of the figures, whose violent gestures do not “rhyme”. In its turn, The Betrayal and Capture of Christ (L. 20) exerted an influence on the work of successive generations of artists. A woodcut of the same title datable to 1507 (B. 34) from The Passion series by Hans Leonhard Schäufelein may serve as an instance of this.

Schongauer included in his Betrayal and Capture of Christ two plant motifs with a symbolic significance, which are juxtaposed to produce a strong emotional effect. They are the Verbascum thapsus, the great mullein, or shepherd’s club, used by Schongauer more than once in his scenes of the life of Christ as a symbol of His glory; and a withered tree, a symbol of death common in fifteenth-century art.

10. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), The Virgin and Child in a Courtyard. C. 1480–90. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 169 x 123 mm. Provenance: Yegor Makovsky, 1925. (Lugt, Supplément, 885a). Inv. No. 100975; Bartsch 32; Lehrs 38

A dead tree figures in another of Schongauer’s prints in our book, The Virgin and Child in a Courtyard (L. 38), also a work rich in symbols. Here the wall enclosing the yard symbolizes the purity of the Virgin and the dry tree alludes to the early death awaiting Christ.

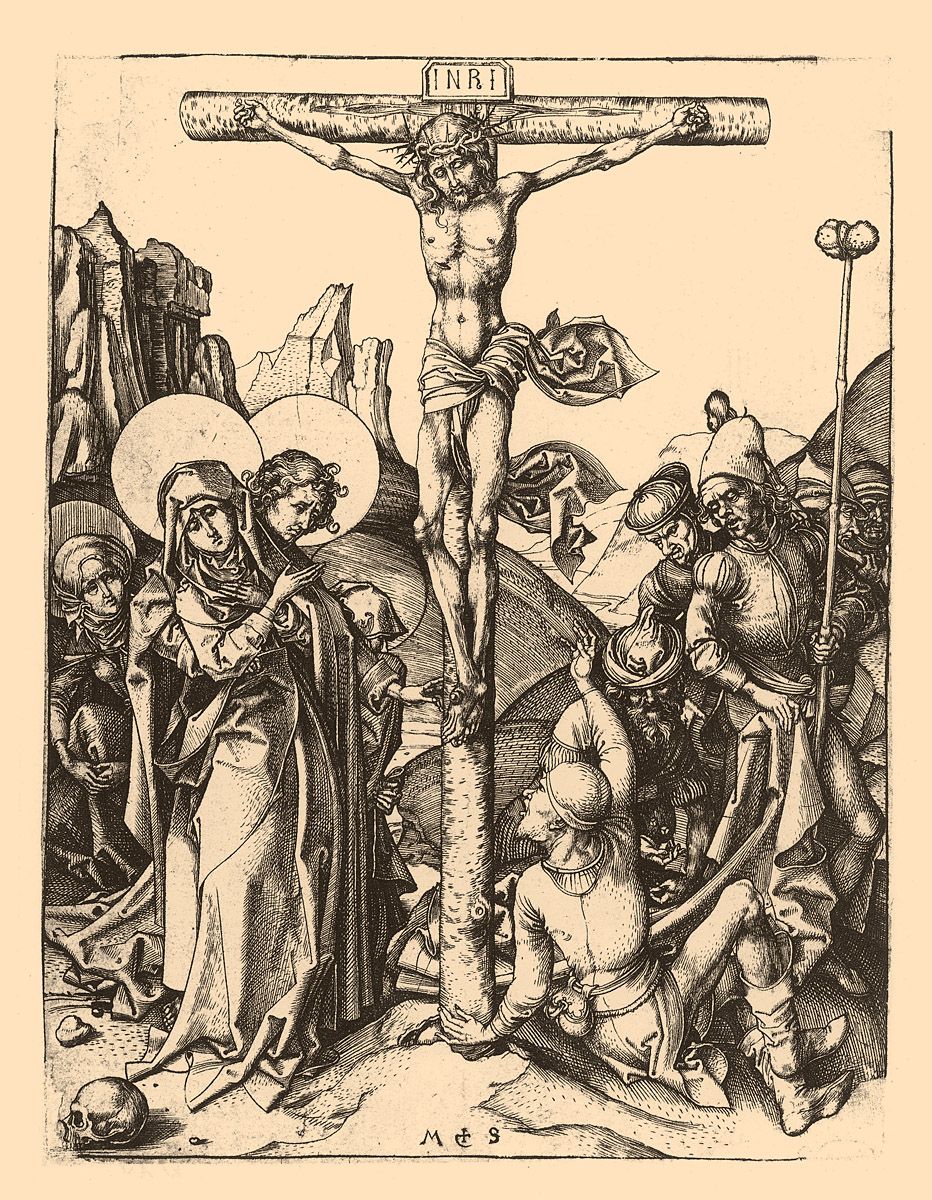

11. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), The Crucifixion. C. 1480. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 195 x 151 mm. Watermark: Profile head with staff and star. Provenance: Yegor Makovsky, 1925 (Lugt, Supplément, 885a). Inv. No. 10097; Bartsch 24; Lehrs 13; Shestack 63

Over the years, Schongauer’s world outlook became increasingly dramatic and somber. His Crucifixion (L. 13), containing but a few objects associated with daily life, has for its background a mountain view so lofty and abstract as to invite comparison with the art of Duccio, or even with Byzantine icons. Not a single blade of grass grows on the rocks, nor is there a sign of any living thing; barren and lifeless, they are a veritable echo of death.

12. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), St. James the Less. C. 1480. VII from The Twelve Apostles series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 87 x 43 mm. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910. Inv. No. 154661; Bartsch 40; Lehrs 52 (as Judas Thaddeus)

Like many other artists of his time, Schongauer engraved the cycle of The Twelve Apostles (L. 41-52). Vasari lists these among the master’s best works. One of them, St. James the Less (L. 52), is included here.

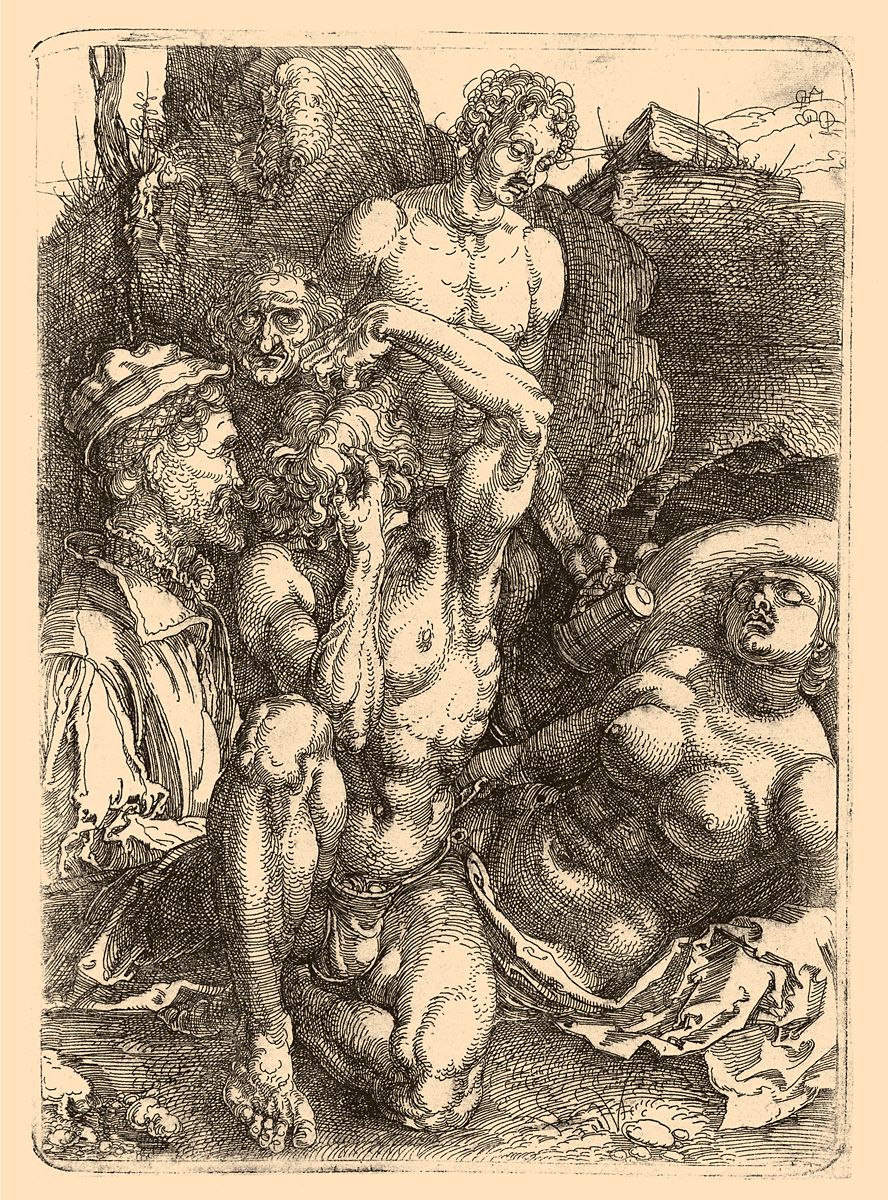

13. Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), Shield with a Stag, Held by a Wild Man. C. 1480–90. IX from The Coats of Arms series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. Diameter 78 mm. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910. Inv. No. 154659; Bartsch 104; Lehrs 103; Shestack 97

The series of Coats of Arms (L. 95-104) was created during Schongauer’s late years. They were supposedly intended as ornamental patterns for goldsmiths, or as a fifteenth-century equivalent of modern visiting-cards, or perhaps as bookplates. They may well have been conceived in the spirit of parody, as mock ensigns of honour. Vasari, however, took them quite seriously, as “alcune arme di signori tedeschi, sostenute da uomini nudi et vestiti e da donne” (IX, 260): several coats of arms of German nobles, supported by men, nude or clothed, and by women.

A sheet from this series, Shield with a Stag, Held by a Wild Man (L. 103), is illustrated in our book. The bearer in the shape of a human creature of fantastic aspect, believed in those days to live in the forests, signified a powerful defender endowed with the strength of a lion, and able to overcome all opponents in the service of the bearer of the coat of arms. The choice of the charges is based on medieval Christian symbolism. Thus, the mountain is meant to suggest divine presence; the stag is an emblem of Christ; and His attribute, the lily-of-the-valley, is allegorical of the well-being of the world, and the cure of the spirit.

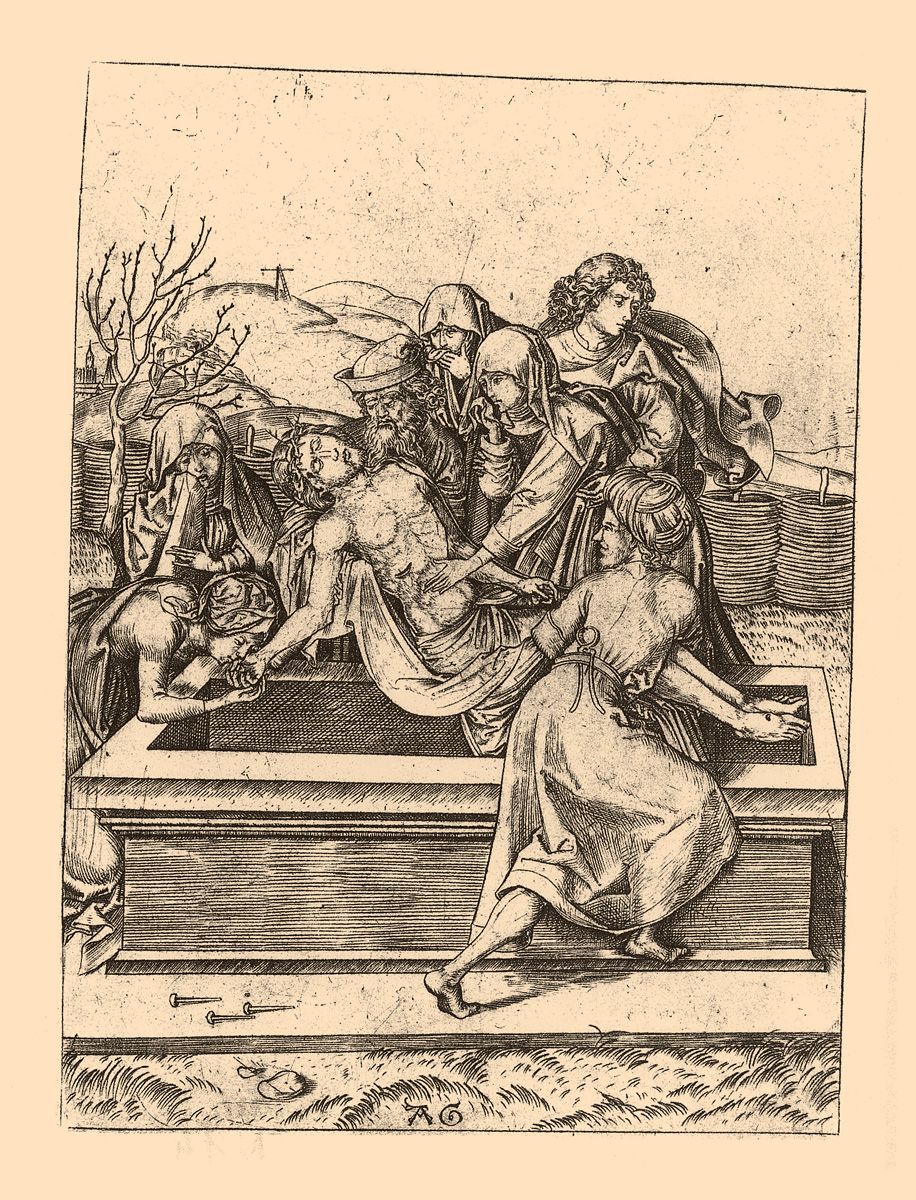

14. Master A. G. (fl. c. 1475–1490), The Entombment. C. 1480–90. X from The Passion series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 144 x 107 mm. Provenance: Joseph Daniel Böhm (Lugt 271, 1442); Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154657; Bartsch 11; Nagler, Mon. 11; Lehrs 15/I

The Hermitage collection of German graphics of the pre-Dürer period is not large. Among its prints is a sheet by Master A. G. (fl. c. 1475-1490) who seems to have served a term of apprenticeship with Schongauer in his workshop at Colmar. The Entombment (L. 15), created in all likelihood in the 1480s when the artist was already settled in Würzburg, is marked by great delicacy of touch. Its engraving techniques bring to mind the manner of Schongauer. Not so its style; the acrid dissonances so characteristic of The Passion series by Schongauer, an artist unrivalled for his skill in the use of contrast while rendering movement, are not present in the print of Master A. G. He obviously preferred the undulating rhythm of Netherlandish art, as exemplified by The Entombment of Dirck Bouts (National Gallery, London), a painting close to our print in the arrangement of the figures.

15. Wenzel von Olmütz (fl. c. 1475–1500), St. Simon. C. 1490. XI from The Twelve Apostles series. Copy after an engraving by Martin Schongauer (Lehrs 51). Signed in monogram. Engraving. 95 x 47 mm. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 34361; Bartsch 40; Lehrs, Olmütz 42; old impression; Lehrs 42

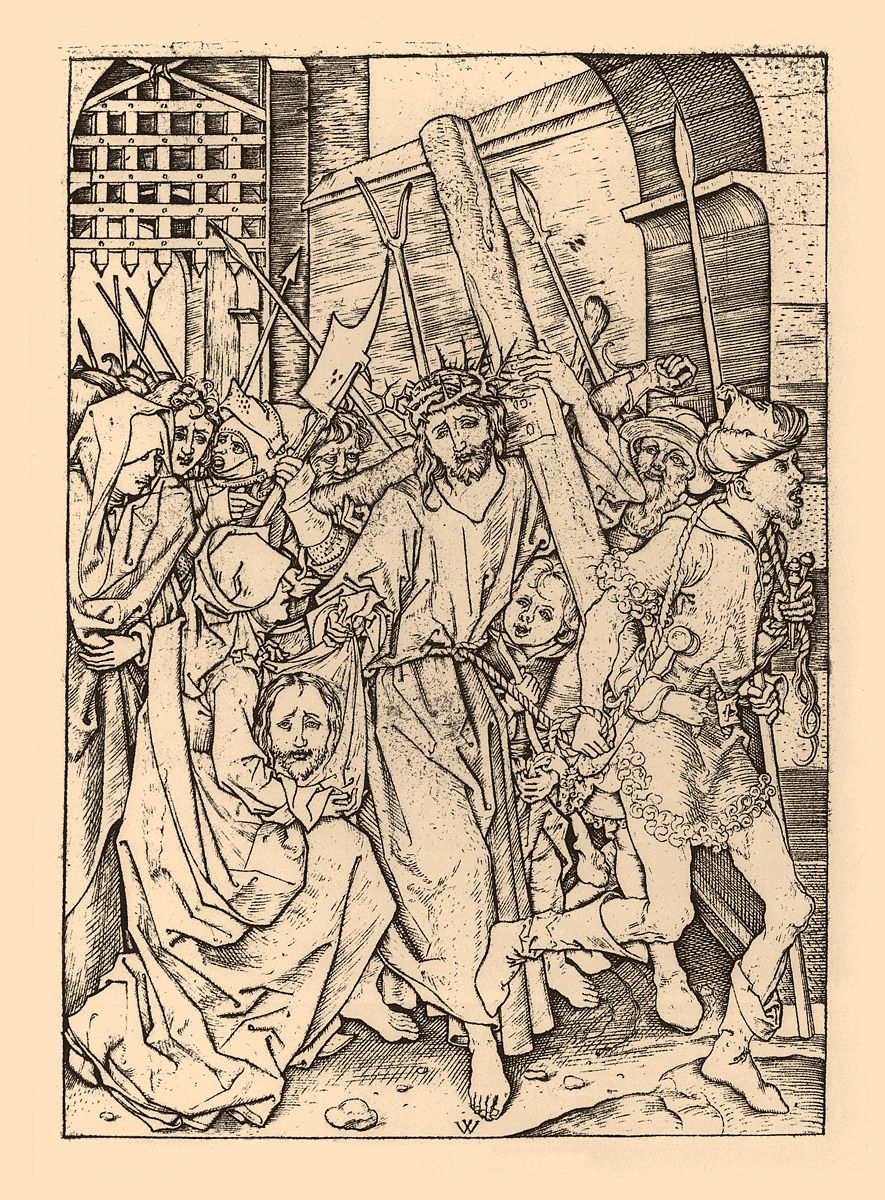

Native of Bohemia, Wenzel von Olmütz (fl. c. 1475-1500) may also be assigned to the school of Schongauer, for of his ninety-one surviving works, forty-three are copies from the great Alsatian master. The art of Wenzel von Olmütz is represented in the Hermitage by several prints. Two of these, St. Simon (L. 42) and The Bearing of the Cross with St. Veronica (L. 16), repeat Schongauer’s compositions of the same subjects, executed during the 1480s. In his interpretation of the originals, however, Wenzel von Olmutz showed considerable independence: he rendered the tonal, dimensional and spatial relations freely, and varied the structural harmony of Schongauer’s prints by introducing a linear rhythm of his own, which imparts to his work a distinct individual flavor and lends it a peculiar charm.

16. Wenzel von Olmütz (fl. c. 1475–1500), The Bearing of the Cross with St. Veronica. C. 1490. VIII from The Passion series. Copy after an engraving by Martin Schongauer (Lehrs 26). Signed in monogram. Engraving. 162 x 116 mm. Watermark: Small town gate. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 143805; Bartsch 11; Lehrs, Olmütz 11; Lehrs 16, old impression

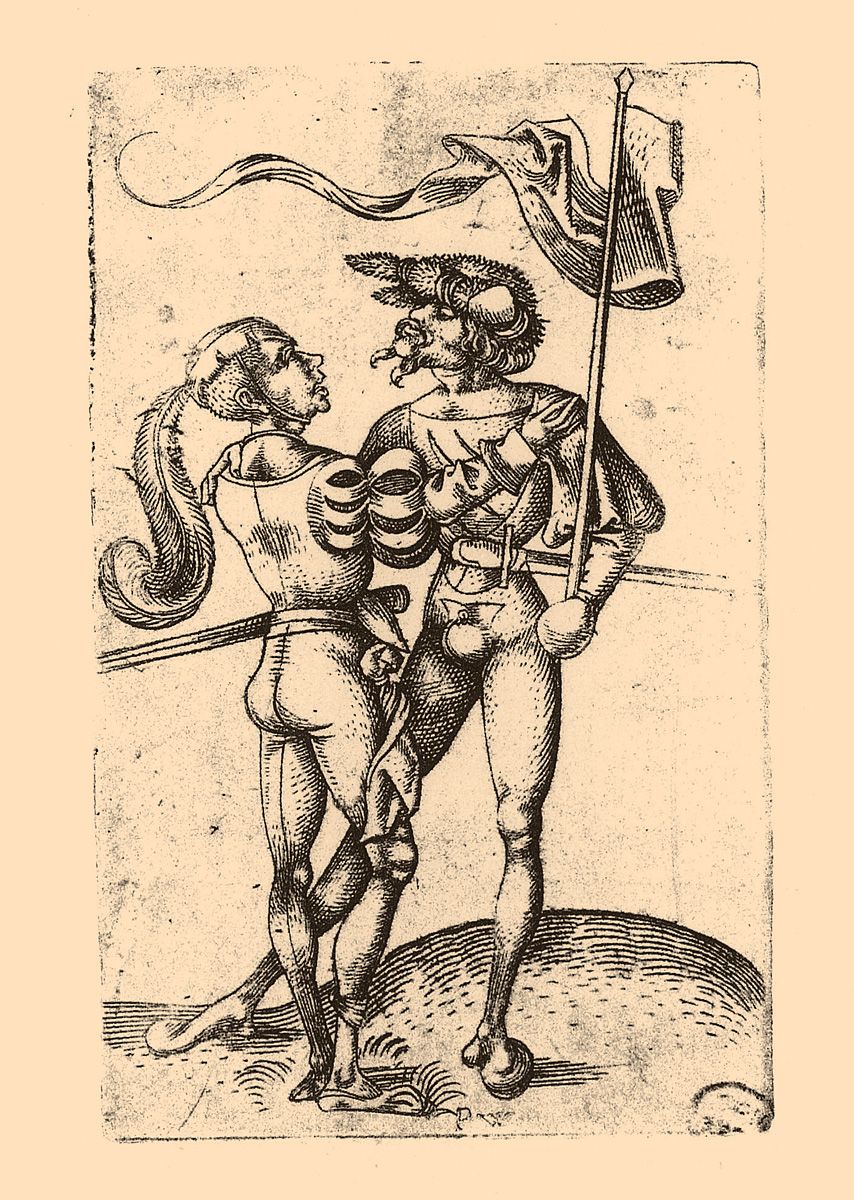

17. Master P. W. of Cologne (fl. c. 1490–1510), Two Soldiers with a Banner. C. 1500. Companion piece to Two Soldiers with a Halberd (Lehrs 15). Signed in monogram. Engraving. 101 x 64 mm. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 144556; Bartsch 3; Nagler, Mon. 7; Lehrs 14

The Hermitage collection includes only a single example from the œuvre of Master P. W. of Cologne (fl. c. 1490-1510), Two Soldiers with a Banner (L. 14). This print, like all of his works, is distinguished by a sharp and elegant drawing style. The subject, as well as that of its companion piece, Two Soldiers with a Halberd (L. 15), may be assumed to reflect the author’s personal observations of Emperor Maximilian I’s campaign against the Swiss, of the year 1499. The Two Soldiers with a Banner, without a doubt, postdates Dürer’s Six Soldiers (B. 88) executed in 1496 – that work was quite obviously known to Master P. W. But it was created before 1502–3 when Master P. W.’s famous Deck of Playing Cards (L. 20-91) was produced, to judge by the fashions in dress and the general style of execution.

18. Master B. G. (fl. c. 1470–1490), Empty Shield Held by a Peasant Woman.C. 1490. Signed in monogram. Engraving. Diameter 92 mm. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 143803; Passavant 30; Nagler, Mon. 33; Lehrs 37

Of the work of Master B. G. (fl. c. 1470–1490) who lived, in all probability, somewhere on the Middle Rhine, in the area of Frankfurt, the Hermitage owns two examples: Empty Shield Held by a Peasant Woman (L. 37), and The Arms of Rohrbach and Holzhausen (L. 40). The sheet representing the arms of the two patrician families of Frankfurt may be a copy of a drawing (now lost) by Master of the Housebook, another artist of the Middle Rhine area, who exerted a strong influence on Master B. G. The former work, of which a woodcut copy was made by Hans Schäufelein as early as 1535, in his Three of Acorns (G. 1112) for a set of playing cards, may have been inspired by such prints of Master of the Housebook as Young Man and Old Woman (L. 73) and Peasant Woman with a Yarn and an Empty Shield (L. 82).

While sharing with Master of the Housebook his interest in peasant subjects, Master B. G., who has a pronounced moralizing tendency, places a stronger emphasis on the more brutal side of human nature than did his predecessor. In his Empty Shield Held by a Peasant Woman (L. 37), the woman is represented as quite drunk, in the act of raising her skirt; the shield she is holding lacks a coat of arms, an ensign of honor; by her side is a jug, an object not infrequently used in the German and Netherlandish art of the period as an allusion to the low, carnal aspect of the female sex. The artist’s keen sense of the grotesque, and his vivid imagination, make up for the crudeness of the drawing, and give liveliness and meaning to his print.

19. Master B. G. (fl. c. 1470–1490), The Arms of Rohrbach and Holzhausen.C. 1480–90. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 97 x 95 mm. Provenance: Alfred Beurdeley (?), 1885; Baron Alexander. Stieglitz; Museum of the School of Art and Design, 1932, Inv. No. 288669; Passavant 40; Nagler, Mon., p. 890; Lehrs 40, impression; 1856; Shestack 140

20. Monogrammist M. Z. (fl. c. 1500), St. Catherine of Alexandria. C. 1500. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 124 x 87 mm. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154666; Bartsch 11; Nagler 11; Lehrs 8

The two prints of the highly gifted Monogrammist M. Z., active in Munich about the year 1500, St. Catherine of Alexandria (L. 8) and The Embrace (L. 16), like other works by this master, are not copies but original creations of the engraver.

St. Catherine of Alexandria and two other prints, St. Margaret (L. 10) and St. Ursula (L. 11), form a graphic triptych dedicated to the cult of virginity and Christian martyrdom.

21. Monogrammist M. Z. (fl. c. 1500), The Embrace. 1503. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 151 x 116 mm. Provenance: Alfred Beurdeley (?) 1885; Baron Alexander Stieglitz; Museum of the School of Art and Design, 1932; Inv. No. 288872; Bartsch 15; Lehrs 16; Shestack 149

The Embrace (L. 16) is an interesting illustration of the practice, common in medieval art, of investing each little detail with a double significance, and using both its direct sense and its metaphorical connotations. Thus, the open cupboard and the unlocked door suggest that the mistress of the house is a woman of easy virtue; this idea is echoed in the shape of the door-fastening, which is suggestive of a phallic symbol; while the mirror is an allusion to the vices of Vanity and Voluptuousness.

The work of Monogrammist M. Z. is a product of a peculiar artistic vision which, while still retaining some features of the past, is nevertheless oriented toward the coming sixteenth century. His love of Gothic elongated forms, of agitated, angular outline, of labyrinths of gracefully fluted drapery folds, links him to German fifteenth-century engraving. But his free handling of the burin, his spontaneity in the rendering of light emanating from a multitude of sources and producing reflexes and rich shimmering shadows, the airiness of his landscapes, and an almost impressionistic quality distinguishing them, are all features that were to be taken up by sixteenth-century art, and to grow into its leading principles.

22. Israhel van Meckenem (c. 1445–1503), St. Agnes. C. 1490. Copy after an engraving by Martin Schongauer (Lehrs 67). Signed in monogram (cut). Engraving. 143 x 98 mm (cut). Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154665; Bartsch 119; Geisberg, Verzeichnis, 320; Lehrs 387

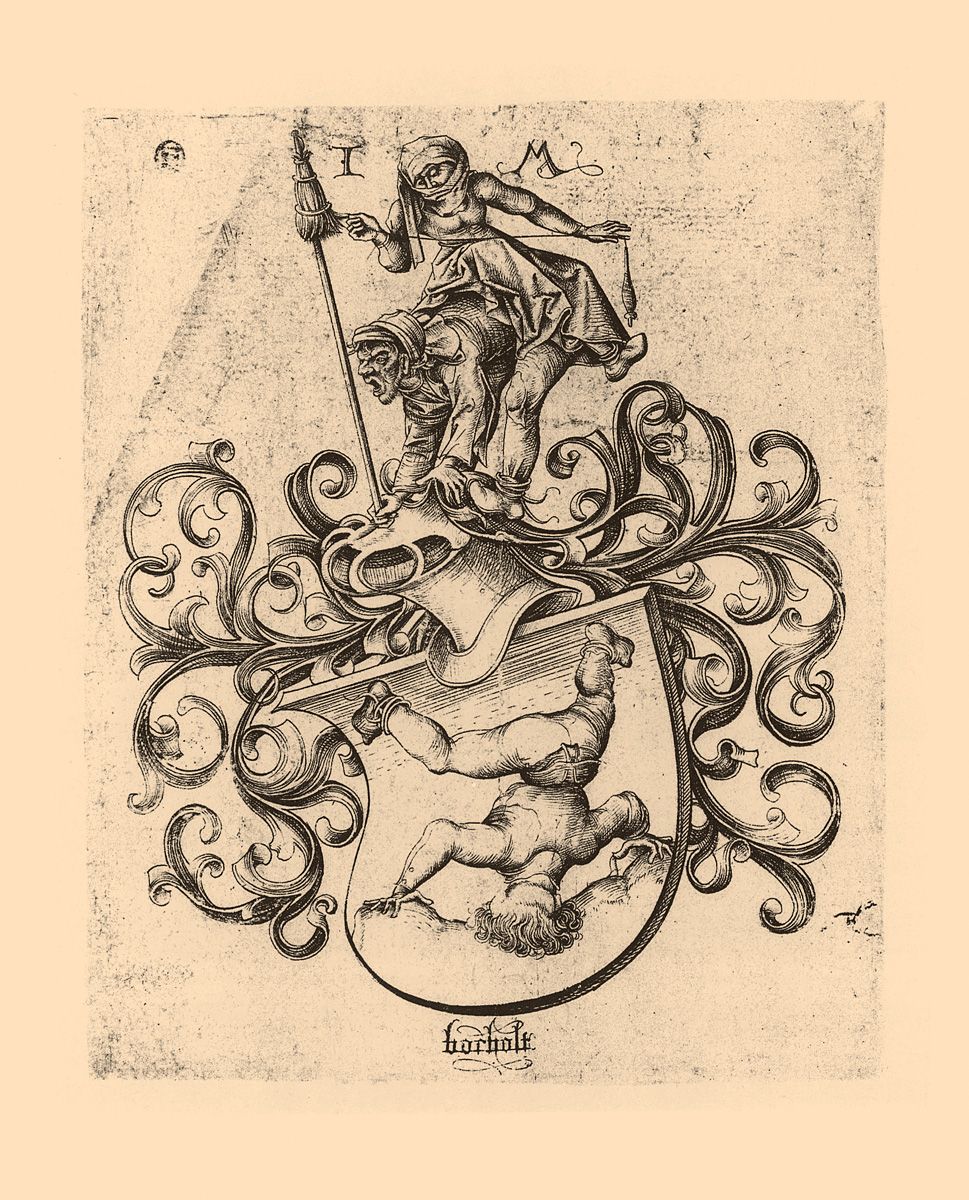

The prints of Israhel van Meckenem (c. 1445-1503) included in this volume are copies from other artists, as are most of the works of this prolific master. They are St. Agnes (L. 387), a reproduction of Schongauer’s engraving (L. 67), and Coat of Arms with a Tumbling Boy (L. 521), a copy of a dry point print (L. 91) by the Master of the Housebook, both dating from the 1480s or 1490s.

23. Israhel van Meckenem (c. 1445–1503), Coat of Arms with a Tumbling Boy. C. 1480–90. Copy after an engraving by the Master of the Housebook (Lehrs 91). Signed in monogram and inscribed: bocholt. Engraving. 146 x 119 mm. Provenance: Alfred Beurdeley (?) 1885; Baron Alexander Stieglitz; Museum of the School of Art and Design, 1932; Inv. No. 288866; Bartsch 194; Passavant 194; Geisberg, Verzeichnis 442; Lehrs 521; Shestack 206

By its content, the Coat of Arms with a Tumbling Boy must be grouped with numerous fifteenth-century representations based on a jocose treatment of the heraldic theme, where the holder is chosen to harmonize with the main device. In this case, the boy standing on his head is intended to personify the idea of a topsy-turvy world. The concept of the general unreasonableness of things is further developed in the grotesque subject topping the shield: an ugly woman with a distaff riding on the back of a man who stands on all fours – an allusion to the legend concerning Aristotle being duped by the courtesan Phyllis.

The Hermitage impressions, though few, give a clear enough idea of the work of Israhel van Meckenem as a copyist. In his harsh and angular manner of drawing, the original composition emerges in an entirely new graphic interpretation, no longer marked by the soft plasticity characteristic of the Master of the Housebook’s style. It is interesting to note that Israhel van Meckenem realized this and, believing his copies to possess artistic value in their own right, marked them with his initials and with the name of the town of Bocholt where he lived.

24. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Holy Family with a Locust. C. 1495. Signed in monogram; falsely dated: 1491 (in ink). Engraving. 241 x 188 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34471; Barisch 44; Dodgson, A. D. 4; Meder 42 (b); Hollstein 42

The work of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) is the epitome of the flowering of German art in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. His activity marks one of the most significant phases in the history of European culture. His rare genius of draughtsmanship, and the deeply humane content of his works which deal with matters of permanent importance to men of all times, raise Dürer to the level of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Michelangelo.

The Hermitage owns a superb collection of Dürer’s prints, a circumstance that has enabled us to select for this volume a number of excellent examples illustrating different periods of the great master’s artistic career.

The Holy Family with a Locust (B. 44), the earliest of the prints marked with Dürer’s monogram, was executed about the year 1495, immediately on the artist’s return from his first Italian journey. Though his Italian impressions were of recent date, the ideals of Northern art had lost none of their attraction for Dürer. The subject – Mary seated on a grassy bench symbolizing the enclosed garden, or Paradise – is associated with the cult of the virginity of Mary, particularly widespread in the fifteenth century. St Joseph is shown asleep, to indicate his passive role; the images of God the Father and the Holy Spirit in the heavens above further develop the theme of the divine origin of Jesus. The background view can be recognized as a scene in the vicinity of Nuremberg; yet it includes some motifs reminiscent of Southern Tyrol. In his treatment of landscape, however, even at this early stage in his career, Dürer follows the practice of Italian artists in basing his work to some extent on preliminary sketches from nature. Thus, under the impact of his Italian experiences, reflected here in a variety of ways, new tendencies are seen to develop within the Late Gothic framework of Dürer’s artistic thinking.

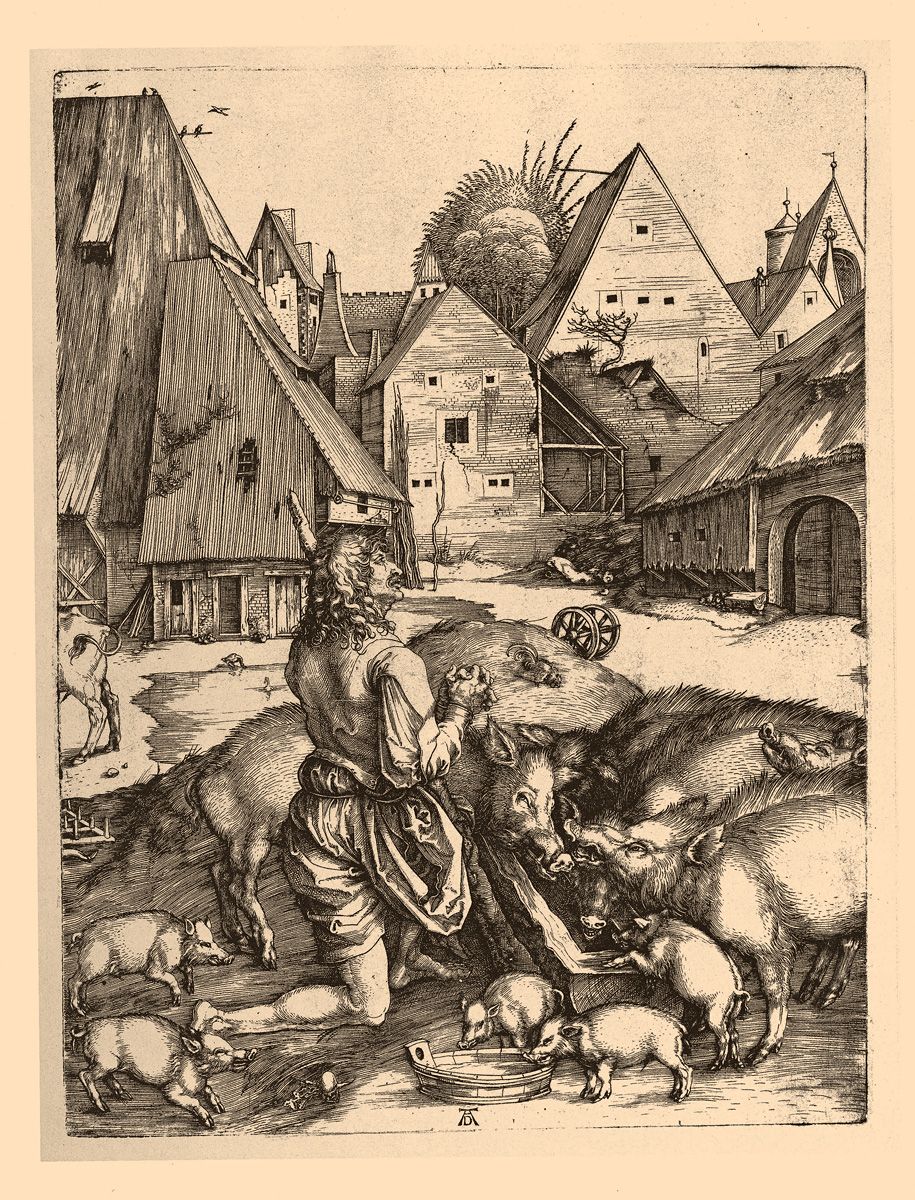

25. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Prodigal Son. C. 1496. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 247 x 191 mm. Watermark: Bull’s head with triangle, with staff and flower. Provenance: Antiquariat, 1932; Inv. No. 276690; Bartsch 28; Dodgson, A. D. 10; Meder 28 (a); Hollstein 28

The Prodigal Son (B. 28) was engraved c. 1496. The hero of the Gospel parable is represented, according to Vasari, “a uso di villano” (XI, 261): in the guise of a peasant. In our opinion, though, The Prodigal Son, if compared with Dürer’s self-portraits of the period, will be found to have a facial resemblance to the artist himself. However accurate this conjecture may or may not be, the emotional tension and the psychological effectiveness of the representation are such as to leave no doubt of the author’s deeply personal attitude towards the subject. The complex message of the scene, which is to symbolize man’s progress through earthly life, is heightened by the force of the artist’s emotional involvement. This is a sign of the times, a feature of Renaissance art with its passionate interest in human individuality, which had come to replace the impersonal spirit of medieval art.

26. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Virgin and Child with a Monkey. C. 1496–98. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 189 x 121 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34468; Bartsch 42; Dodgson, A. D. 22; Meder 30 (a); Hollstein 30

The Virgin and Child with a Monkey (B. 42) must have been executed sometime between the years 1496 and 1498, after the artist’s return from a journey to Italy. In spite of the freshness of his Italian impressions, the print is imbued with the spirit of old German art. Particularly strong is the influence of Schongauer. The Virgin is shown seated upon a grassy bench in a graceful if somewhat conventional attitude; the elegantly draped folds of Her garments seem to form a kind of pedestal for Her figure.

Ample use is made of the language of religious symbolism, which is in perfect keeping with the principles of late medieval art. The chained monkey may be intended to suggest the folly of thoughtless imitation, or Evil made captive by the sanctity of the Virgin; and the bird in the hand of the Infant Christ, to serve as an allusion to His sacrificing Himself for the sake of mankind. Compared with The Holy Family with a Locust (B. 44), executed some years earlier, this print is distinguished by a greater fluidity of line, and a more convincing rendering of rounded forms.

27. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Promenade. C. 1496–98. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 175 x 121 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34502; Bartsch 94; Dodgson, A. D. 9; Meder 83/I (a); Hollstein 83/I

The Promenade (B. 94) seems to be contemporary with Dürer’s illustrations for the Apocalypse (B. 60-75), created between 1496 and 1498. It reflects his chiliastic notions, dealing with the future end of the world and the second coming of Christ – a theme to which the artist reverted time and again in the course of his career: the idea of Death carrying off all living things permanently dwelt in his mind. That this theme should become more important with the approach of the year 1500 was only natural, since the end of the world, prophesied in Revelation, was then generally expected to come at the turn of the century. Thoughts of inevitable doom, and of the brevity of earthly existence, were reflected in The Promenade, a work of Dürer’s young years, with passionate intensity.

The mournful mood permeating the print is enhanced by the use of contrast: the large foreground figures are placed in juxtaposition to small-scale landscape motifs; the sublime aloofness of the main characters is contrasted to numerous chance details connected with everyday existence; the slow and dreamy rhythm of their progress, to the violent suddenness of Death; and the flowering plant next to the lovers, to the withered tree from behind which a skeleton is peeping.

The copy (L. 513) of this print, made by Israhel van Meckenem almost immediately after its creation, is inscribed: Ten is niet al tzijt vastauent. Der doet kompt en brengt Aeuent (It is not always feasting-time. Death comes and brings an end to all).

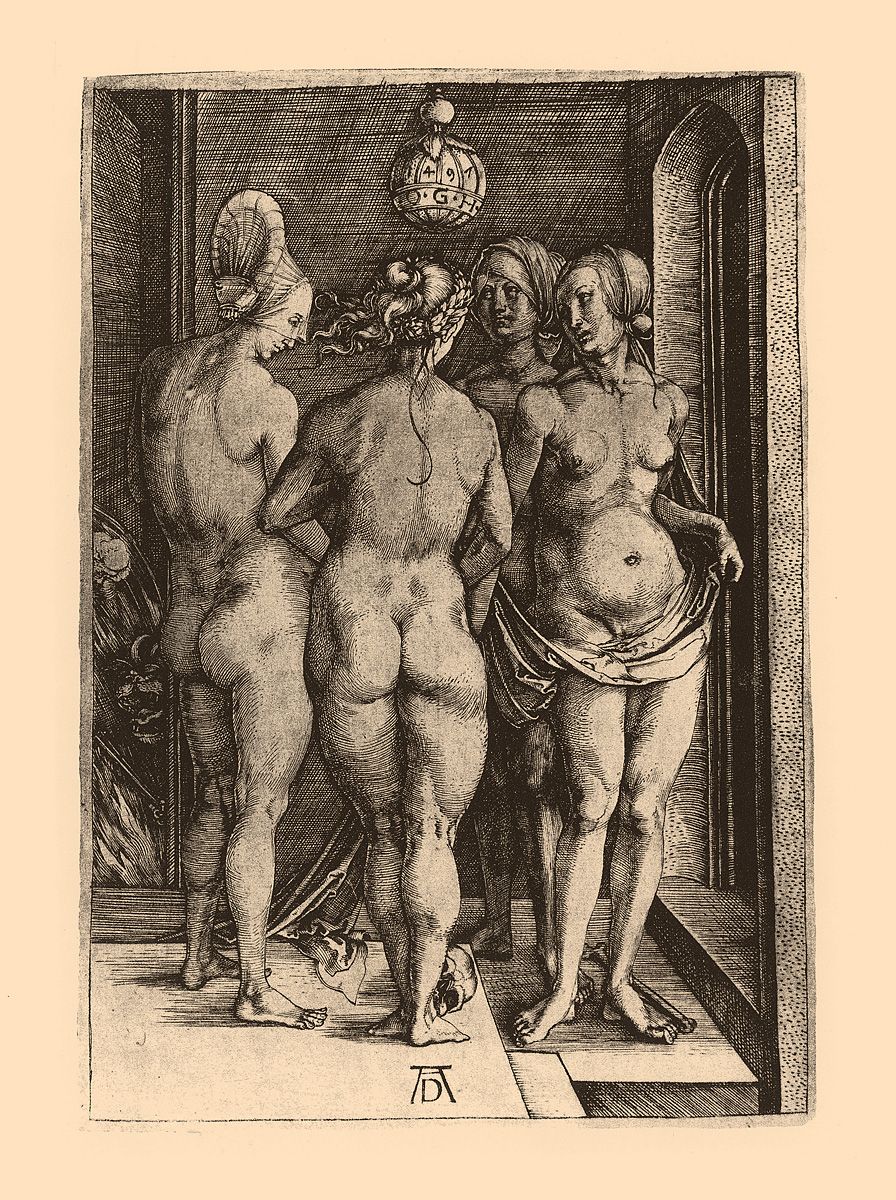

28. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Four Naked Women. 1497. Signed in monogram, dated and inscribed: O.G.H. [O Gott Hute (?)] or [Origo Generis Humani (?)] or [Obsidium Generis Humani (?)] or [Odium Generis Humani (?)]. Engraving. 191 x 135 mm. Provenance: O. Trtetsyak, 1945; Inv. No. 357158; Bartsch 75; Dodgson, A. D. 14; Meder 69 (a?); Hollstein 69

Dürer’s engraving Four Naked Women (B. 75) has no definite subject. Its meaning has been variously interpreted: the figures were supposed to personify the four ages of man; or to represent the four Horae, or the four seasons of the year. The absence of the relevant attributes precludes acceptance of any of these interpretations.

A copy (B. 62), executed by Nicoletto Rosex da Modena, has an inscription which suggests that three of the figures are the Olympian goddesses involved in the Judgment of Paris, and the fourth is a personification of Discord. But in rendering this version of the subject, the Italian artist had to introduce changes into the background, leaving out such motifs as the flames and part of a devil’s figure, directly alluding to hell; in this way he deviated from the original in a rather distinct manner. For this reason it does not seem possible to regard the subject of Nicoletto Rosex da Modena’s copy as identical with that of Dürer’s print.

The concept of the Four Naked Women (B. 75) seems to be connected with medieval notions of the sinful, diabolic nature of nakedness. The letters on the lamp, which read as O.G.H., most probably stand for the words Odium Generis Humani, the [Devil’s] Hatred of the Human Race. The women are represented with hellfire in the background; the skull and bones at their feet are an allusion to their sins, and to the Original Sin which brought death into the world.

The meaning of the print may be further elucidated by comparing it with other contemporary works of a like nature, based on similar religious notions. One of them, the engraving Memento mori (L. 20) executed by Monogrammist M. Z. between c. 1500 and 1502, is clearly inspired by Dürer’s work. Here the woman has a variety of attributes symbolic of moral and religious censure of her nakedness: the prickly flower of evil which, according to tradition, was the only plant not to wither in sorrow for the death of Christ; the skull, here an allusion to the Fall; and the sun-disk, a symbol of the mortality of the human race. The etching Volupta (B. 46) by Daniel Hopfer, somewhat later in date, is also thematically connected with the Four Naked Women; the nude woman is surrounded by devils dancing to the music of Eros; she has in her hand a thistle, the devil’s flower, and a skull at her feet.

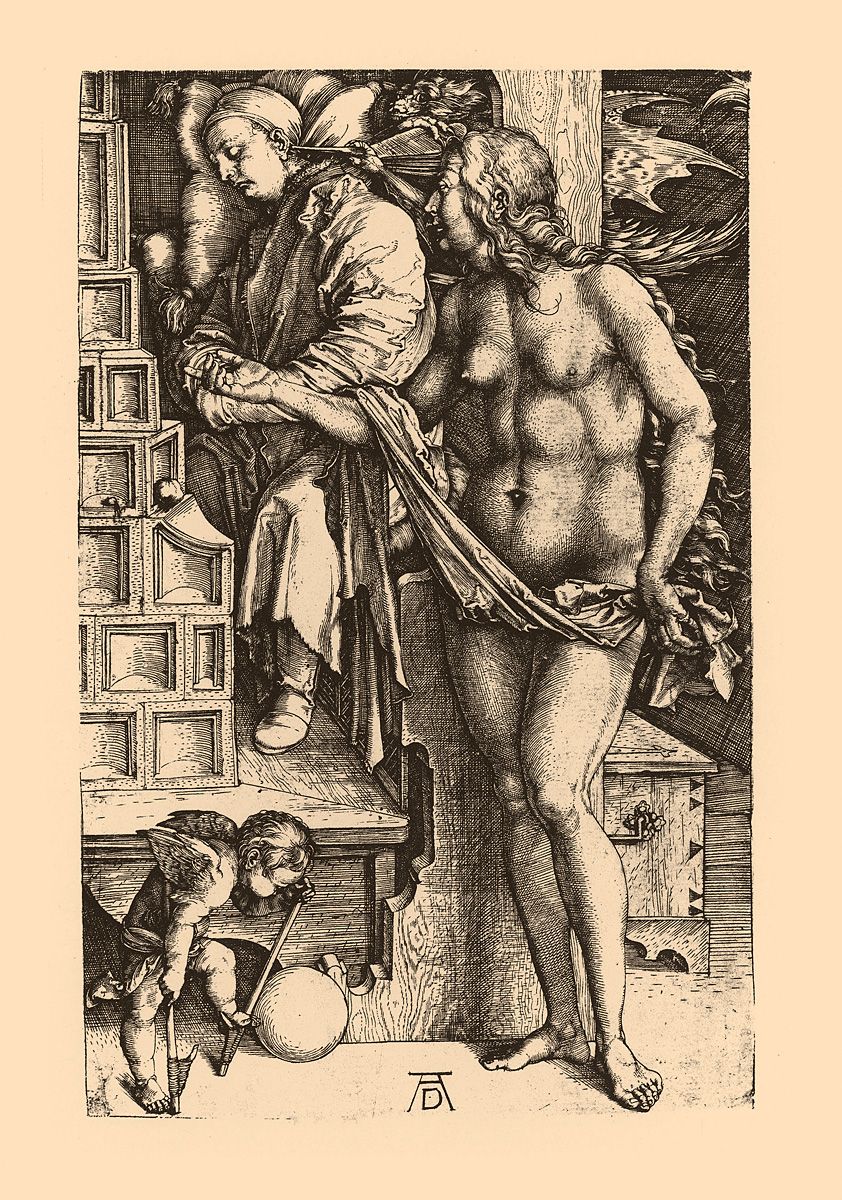

29. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Dream. C. 1497–98. Signed in monogram Engraving. 187 x 120 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34503; Bartsch 76; Dodgson, A. D. 28; Meder 70 (a); Hollstein 70

The Dream (B. 76) has a certain affinity with the Four Naked Women as regards its basic concept, the diabolic nature of female nakedness. The subject of the print seems to have been inspired by a medieval legend telling of a man who, while engaged in a game of ball, took off a ring which impeded his movements, and placed it on a finger of a statue of Venus. Upon this, the mysterious statue turned her hand in a manner to make the ring impossible to remove; and later the goddess herself appeared to the man in a dream. Since the early Middle Ages, the Roman goddess of love was regarded by the Christian Church as a she-devil. In The Dream she is shown accompanied by a devil flying directly at the sleeping man.

As is always the case with Dürer, this print includes some details which have nothing to do with the story itself but serve to create a context necessary for a proper understanding of the subject. The relationship between the figures and the surrounding objects is allegorical rather than real. That the man is asleep near a stove suggests a somnolent and idle state of a Christian soul when, by yielding to the temptations of Venus and her frolicsome son, it succumbs to the powers of the Evil One, the author of all false, devil-inspired dreams. The fruit lying on a tile in the stove invites associations with the forbidden fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and is thus an allusion to the Fall.

30. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Sea Monster. C. 1497–98. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 247 x 186 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804 Inv.; No. 34507 Bartsch 71 (as Amymone and Triton); Dodgson, A. D. 30; Meder 66 (a); Hollstein 66

The Sea Monster (B. 71), executed in 1497 or 1498, is one of the prints inspired by the art of classical antiquity where the motif of a woman riding on the back of a sea god was widely used. The scene of a beautiful woman being carried away by a marine demon occurs on many engraved gems of the period before Christ. During the Renaissance, this subject was frequently represented in minor sculpture, the decorative arts and graphic works. Andrea Mantegna’s Battle of the Sea Gods (H. 6), with the figures of young girls mounted on Fish Eaters, was suggested by classical reliefs. An influence of this engraving, as well as of antique and Renaissance sculptures and reliefs of similar subjects, is clearly felt in Dürer’s Sea Monster.

Attempts have been made to identify the story of the print with the myth of Syma and Glaukos, the Rape of Amymone, and a variety of other tales current in ancient Greece and Rome; also, with a medieval legend of a river god marrying a mortal woman, and with the facetiae of Poggio Bracciolini telling how a woman was carried away by a monster from the deep, who had swum to the coast. The seeking of literary parallels for the subject of the print is not without grounds, since the basis for the formation of a stable plastic version of this motif was really provided by ancient lore. Yet The Sea Monster seems to have been created rather under the immediate impact of the works of the visual arts than as a result of investigating the intricacies of the plot in the numerous literary sources. Vasari, to whom the sheet was known, describes its subject as “una ninfa portata via da un mostro marino” (IX, 261): a nymph being carried away by a marine monster. In his Netherlands Diary Dürer himself referred to the composition as just Meerwunder. We may safely conclude from this that the author’s own concept was of a general enough nature, and that he aimed at rendering the gist of the story, common to all the works of this group, without going into too much detail.

The Sea Monster enjoyed exceptional popularity. The composition was reproduced on a sixteenth-century cameo by a German master (now at the Hermitage, St. Petersburg); also in a painting (Museum of Fine Arts, Bucharest) by an unknown sixteenth-century Netherlandish artist; and in other works too numerous to list here.

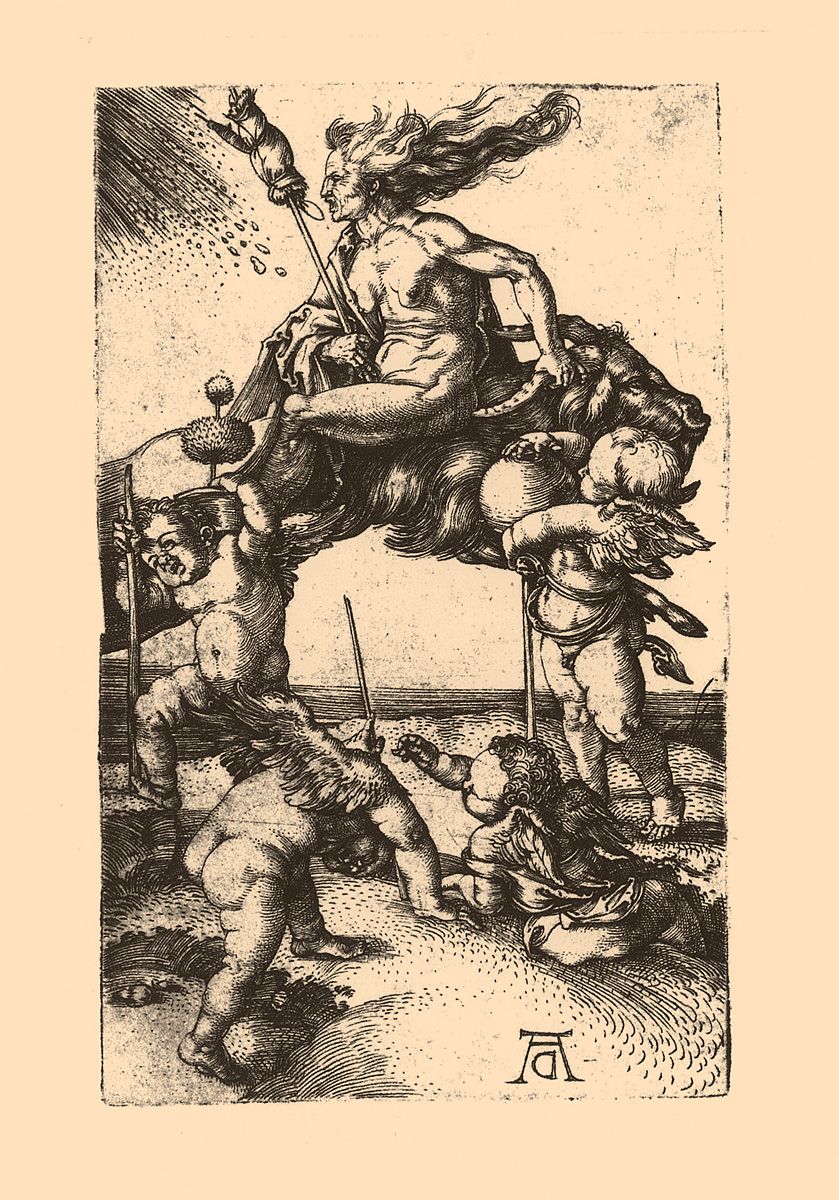

31. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat, Accompanied by Four Putti. C. 1503–5. Signed in monogram; Engraving. 118 x 73 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804, Inv. No. 34426; Bartsch 67; Dodgson, A. D. 41; Meder 68/I (b); Hollstein 68/I

At some time between the years 1503 and 1505, Dürer created his Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat, Accompanied by Four Putti (B. 67). The main figure is a syncretic image which owes some of its features to various pagan and Christian beliefs, and others, to motifs used in works of art and literature.

The old woman, stark naked, her mouth gaping, and her hair blown about by the wind, is reminiscent of the allegory of Envy in Mantegna’s print Battle of the Sea Gods (H. 5). Dürer may also have known the bronze statuette of a witch (now in a private collection, Vienna) of Paduan work, datable to c. 1500; this figure ultimately goes back to Mantegna’s Envy, although the old woman is here shown mounted on a goat.

The motif of Aphrodite riding a goat and accompanied by cupids was frequently used in Hellenistic terra-cottas, in designs on coins, bronze plaques and cameos, owing their inspiration to works of monumental sculpture which have not survived to our day. A cameo carved in agate onyx in the first century A. D. (Museo Nazionale, Naples) may serve as an example; it shows Aphrodite Pandemos as seen by the ancients. The goddess of the desires of the flesh, of carnal passions, is riding a goat, a symbol of lust. Dürer’s Witch retains its semantic connection with the antique prototype: his old woman surrounded by putti is both a witch and a goddess of low passion. Aphrodite Pandemos, being associated in the classical tradition with light and with the signs of the zodiac, was represented among the clouds; in Dürer’s print, the witch upon her goat is soaring in mid-air; this can hardly be mere coincidence. Another feature, establishing a connection between the witch and powers dwelling above the earth, is a number of mysterious heavenly bodies descending upon her in a burst.

About 1507, Dürer’s print was copied by Benedetto Montagna (Pass. 52). Undoubtedly inspired by Dürer’s Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat, Accompanied by Four Putti (B. 67) is the famous woodcut by Hans Baldung Grien, The Witches’ Sabbath (B. 55), which also shows a witch mounted on a goat, flying in the sky. In c. 1520, Marc-Antonio Raimondi created a print called Carcass (B. 426) where the foul sorceress riding a fantastic skeleton has an affinity with Dürer’s witch and the putti have been transformed into little children fearful of the sorceress. In Pieter van der Heyden’s print after the drawing of Pieter Bruegel, St. James the Greater and Magus Hermogenes (R. v. B. 117), executed in 1565, one of the witches is modelled upon Dürer’s. The transformation of the Aphrodite Pandemos of the ancients into a witch in the art of both Northern and Italian masters is easily explained by Christian notions of the sinfulness of sexual love. The Hermitage owns a painting on copper-plate by Adam Elsheimer’s follower, entitled Witch and dated c. 1620, which is a copy of this Dürer print.

32. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Adoration of the Magi. C. 1504. XII from The Life of the Virgin series. Signed in monogram. Woodcut. 301 x 210 mm. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 141877; Bartsch 87; Dodgson 47; Meder 119, edition of 1511, with Latin text; Hollstein 199 (b)

Dürer’s woodcuts of The Life of the Virgin series (B. 76-95) executed between 1502 and 1505, with additions made in 1510 and 1511 – a series exemplified in our book by The Adoration of the Magi (B. 87) dated to c. 1504 – considerably differ from his early prints in their general mood. A new attitude of calm philosophical contemplation has developed to replace the anxiety and emotional turmoil of the artist’s earlier period. Events are presented in a simple and laconic manner, the prevailing tone being one of peaceful calm. It is worthy of notice that Vasari, whose judgement was based on principles of Italian art, and who disapproved of Dürer’s Passion series to the extent of denying his authorship of most later prints on stylistic grounds, declared himself a fervent admirer of The Life of the Virgin sequence.

33. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Small Horse. 1505. Signed in monogram and dated. Engraving. 164 x 108 mm. Watermark: Bull’s head with staff and triangle. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34497; Bartsch 96; Dodgson A. D. 43; Meder 93 (a), Hollstein 93

The Small Horse (B. 96), dated 1505, is one of a number of sheets in which Dürer, influenced by the studies of Leonardo da Vinci, investigated the proportions of the horse, searching for an ideal horse figure.

In Dürer’s day, no prints were produced that had not a meaning of some kind. The Small Horse must also have had in it at least an element of the narrative, but it is not easy to identify, since the artist’s interest was centered on things outside the story. The human figure visible behind the horse is probably Perseus, judging by such characteristic accessories as the winged sandals, the fantastic-looking helmet, and the presence of a weapon, the gift of Hermes – Dürer gave it the form of a halberd. The setting contains no details to negate this suggestion: the ruins are obviously those of a classical edifice; and the flaming fire, a symbol of divine worship, is a pagan metaphor rather than a Christian one.

This composition enjoyed immense popularity, and was repeatedly reproduced; there are numerous free copies of it. Thus, Hans Sebald Beham created his engravings Alexander the Great with His Horse Bucephalus (B. 67) and The Four Horses (B. 217) under the unmistakable influence of The Small Horse (B. 96). As early as the second half of the sixteenth century, Franz Brun, an artist of Strasbourg, produced an epigonic version of his own (B. 95), based on the sheet of the Nuremberg master. Brun’s horse is represented standing in empty space, without any background, on a floor covered with a checkerboard pattern. At a much later time, this queer play of fancy was adopted by Surrealist painters, and became one of their favourite motifs.

All copies of Dürer’s Small Horse, from whatever national school the copyists may come, all versions of the theme, all subjects inspired by it, however varied, have one feature in common: the narrative element is either altogether absent, or appears in a modified form. The key motif of Dürer’s print, the thing that had the strongest appeal for other artists and was invariably reproduced, was the horse itself, shown in side view, and delineated by a resilient outline.

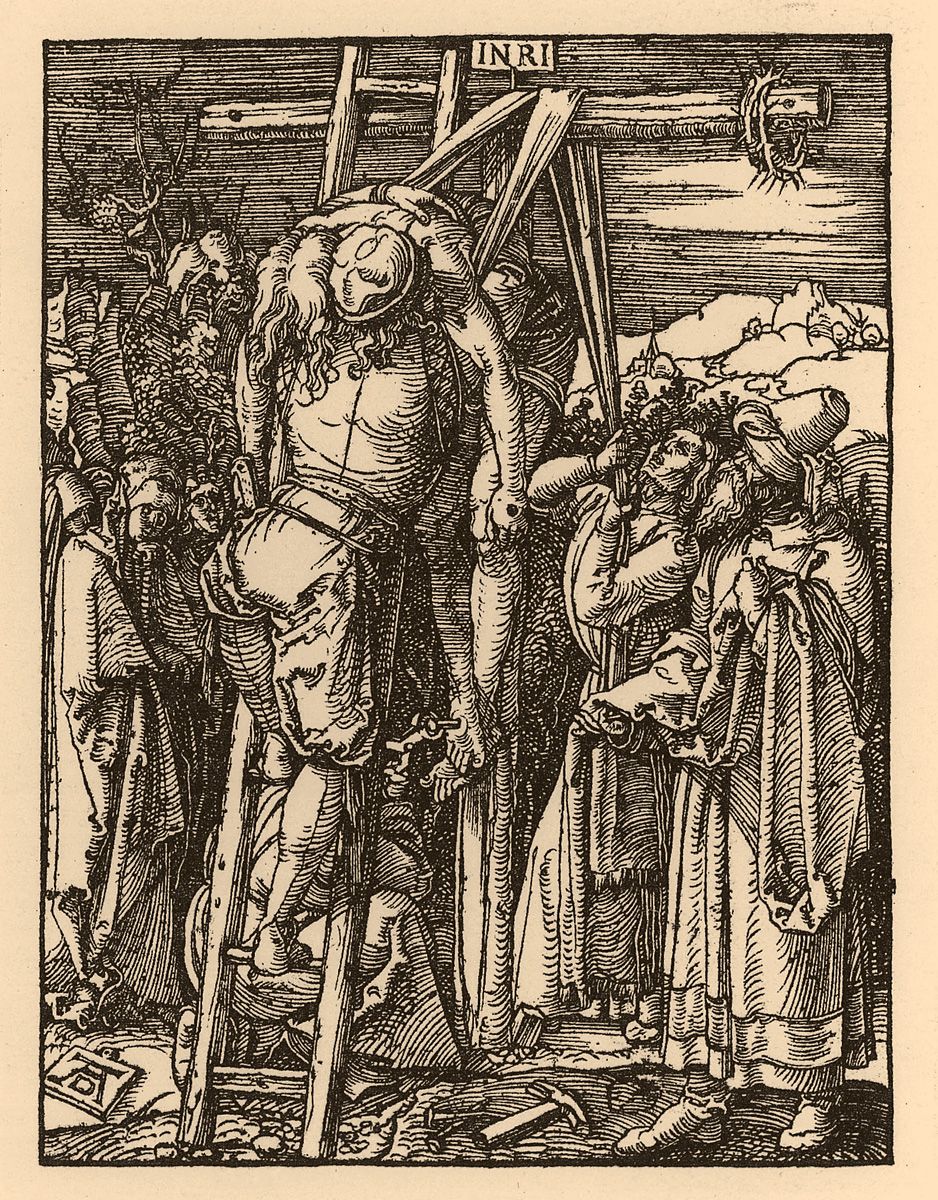

34. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Descent from the Cross. C. 1509–11. XXVII from The Small Passion series. Signed in monogram. Woodcut. 127 x 97 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34651; Bartsch 42; Dodgson 86; Meder 151, before the text edition; Hollstein 151 (a)

During the period between c. 1509 and 1511, Dürer executed a series of woodcuts (B. 16-52) to which he gave, on the title page, the name Passio Christi. This series, generally known as The Small Passion, opens with The Fall of Man (B. 17) and closes with The Last Judgment (B. 52), forming in its entirety a cycle devoted to the theme of the Fall and Deliverance of the Human Race. This cycle was acclaimed all over Europe. Of the great many reproductions made from the woodcuts of The Small Passion set, the Hermitage owns a complete series of copies executed by Marcantonio Raimondi, with masterly coloring by a contemporary artist. The Descent from the Cross (B. 42) is one of the best among the sheets of this series. Curiously, even in this scene treated in the Renaissance manner, Dürer made use of the traditional medieval symbol of the dead tree. Individual motifs of The Descent from the Cross are echoed in French sixteenth-century book illustration, and in Limoges enamels of which the Museum possesses several examples.

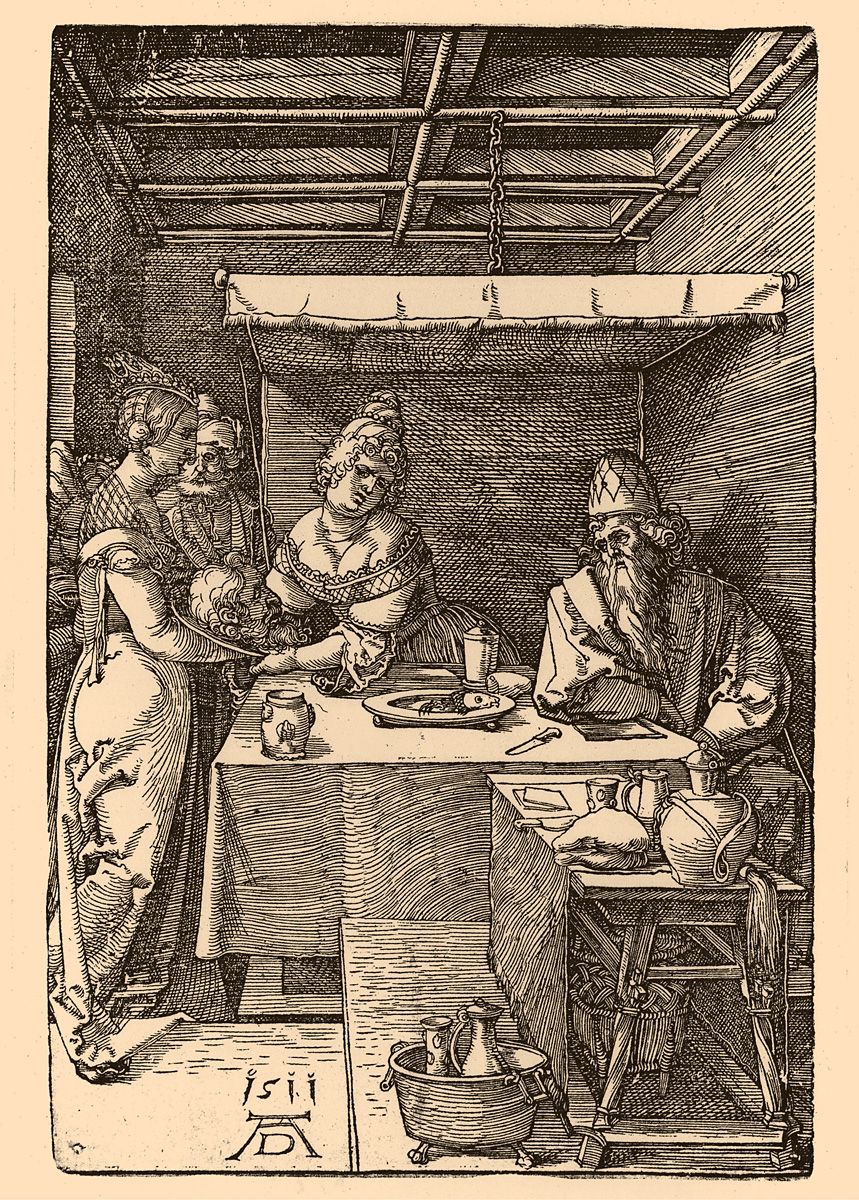

35. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Salome Presenting the Head of St. John the Baptist to Herodias. 1511. Signed in monogram and dated. Woodcut. 193 x 130 mm. Provenance: B. Veselovsky, 19th century (Lugt, Supplément, 312a); Georgy Vereisky, 1929; Inv. No. 149395; Bartsch 126; Dodgson 109; Meder 232 (b), Hollstein 232 (a)

The woodcut Salome Presenting the Head of St. John the Baptist to Herodias (B. 126) was created in 1511 as a companion piece to The Martyrdom of St. John the Baptist (B. 125) dated from 1510. Salome Presenting the Head of St. John the Baptist to Herodias was one of Dürer’s most popular works; already Vasari listed it among the master’s productions. The religious subject is treated here as a vivid genre scene, having a convincingly lifelike quality: a manifestation of the change which Dürer’s style had undergone since his Apocalypse (B. 60-75) – a change, perhaps, not altogether for the better, as it signalled to some extent a departure from that expressionist quality of Schongauer’s Passion series (L. 19-30) which was so dear to Dürer in his early years, and which constituted a specific feature of German national art.

Certain elements in Salome Presenting the Head of St. John the Baptist to Herodias point to the influence of Venetian art on Dürer. The low-cut dress of Herodias brings to mind costumes of Venetian courtesans. The figure of a servant in an exotic headdress like a turban recalls some Oriental characters of the Bellinis, although it is a repetition of Dürer’s own motif from his early print The Turkish Family (B. 95).

We shall mention here only one of the numerous examples illustrative of the popularity of Salome Presenting the Head of St. John the Baptist to Herodias. This is a relief on the wings of an altar executed in the 1520s by Master H. S. R., a woodcarver of the Upper Rhine area (this work is now at the Hermitage).

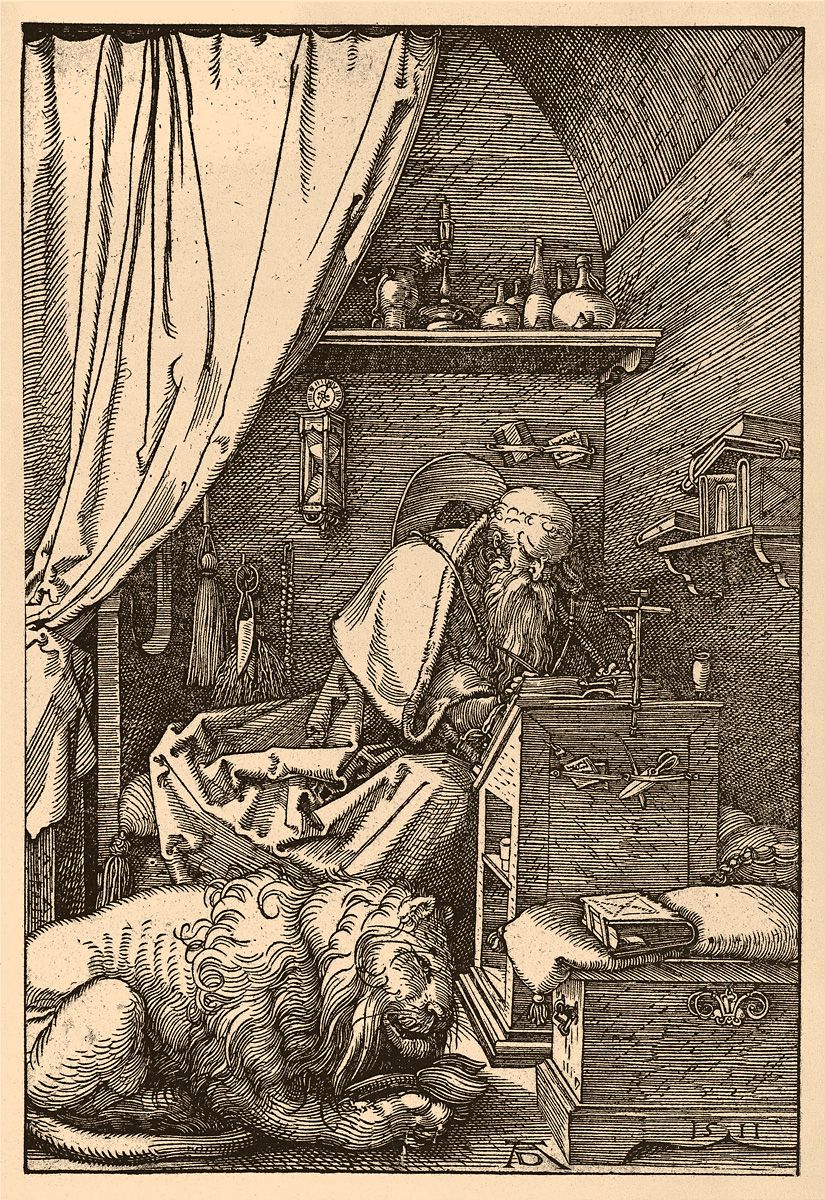

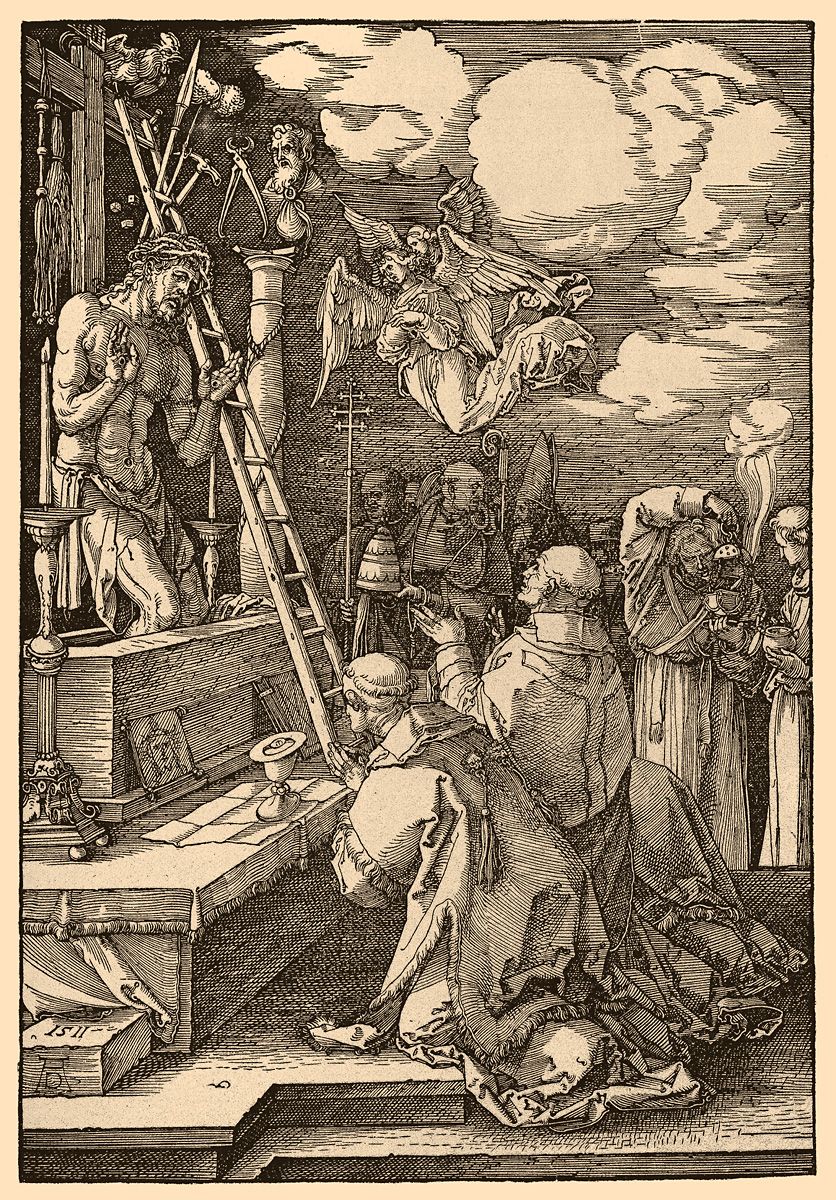

The woodcuts St. Jerome in His Cell (B. 114) and The Mass of St. Gregory (B. 123) date from the same period as the graphic diptych with the history of St. John the Baptist (B. 125 and 126). All these works are stylistically related, employing as the principal means of expression not the line, as in Dürer’s early prints, but areas of hatching and cross-hatching, which enabled the artist to create an illusion of plasticity – an effect never before attained in the technique of woodcut.

36. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), St. Jerome in His Cell. 1511. Signed in monogram and dated. Woodcut. 235 x 160 mm. Watermark: Bull’s head with I Z. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 141888; Bartsch 114; Dodgson 118; Meder 228 (a), Hollstein 228 (a)

The subjects of both St. Jerome in His Cell and The Mass of St. Gregory are distinctly Catholic. St. Jerome’s Latin translation of the Bible, the Vulgate, was authorized in the fifteenth century: thus its importance was once more recognized, in spite of the fact that there already existed several vernacular versions of the Scriptures. The subject of The Mass of St. Gregory, which illustrates the legend of the appearance of the Savior upon the altar during the celebration of the Mass, emphasized to ecclesiastics doubtful of the doctrine of Transubstantiation the significance of that principal rite of the Catholic Church. Yet Dürer’s interpretation of these two related subjects was different: while in The Mass of St. Gregory he followed the iconographic tradition of German and Netherlandish fifteenth-century art where this theme was of frequent occurrence, in St. Jerome in His Cell he was indebted to Venetian influence, in particular, to that of Antonello da Messina’s and Vittorio Carpaccio’s paintings showing theologians deeply immersed in their studies.

37. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Mass of St. Gregory. 1511. Signed in monogram and dated. Woodcut. 230 x 208 mm. Watermark: Small town arms with crown. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34610, Bartsch 123; Dodgson 117; Meder 226 (f?), Hollstein 226

38. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Virgin and Child with a Pear. 1511. Signed in monogram and dated. Engraving. 158 x 108 mm. Watermark: Anchor in 0. Provenance: Antiquariat, 1932; Inv. No. 276733; Bartsch 41; Dodgson, A. D. 54; Meder 33 (a), Hollstein 33

Prints representing the Virgin Mary form a large portion of Dürer’s artistic heritage. One of the most famous, The Virgin and Child with a Pear (B. 41), was created in 1511. The theological programme of the print brings it close to many early works by the master. The Child blesses the universe, and Mary tenders Him the fruit, thereby investing Her son with the mission of redeeming mankind from damnation for Original Sin. The old medieval allegories of German art are also in evidence here: the naked tree devoid of living branches, a reminder of death; and the fortress wall seen in the depth of the composition, a version of the often-recurring motif of the enclosure, traditionally used to symbolize Mary’s purity.

The artist’s style, though seeming to tend towards balance and calm, retains certain traits of the Gothic: this is felt in the angular shapes of drapery folds, creased by mysterious winds, and in the spiral direction of movement in the composition, which is in contrast to the Renaissance principle of contrapposto.

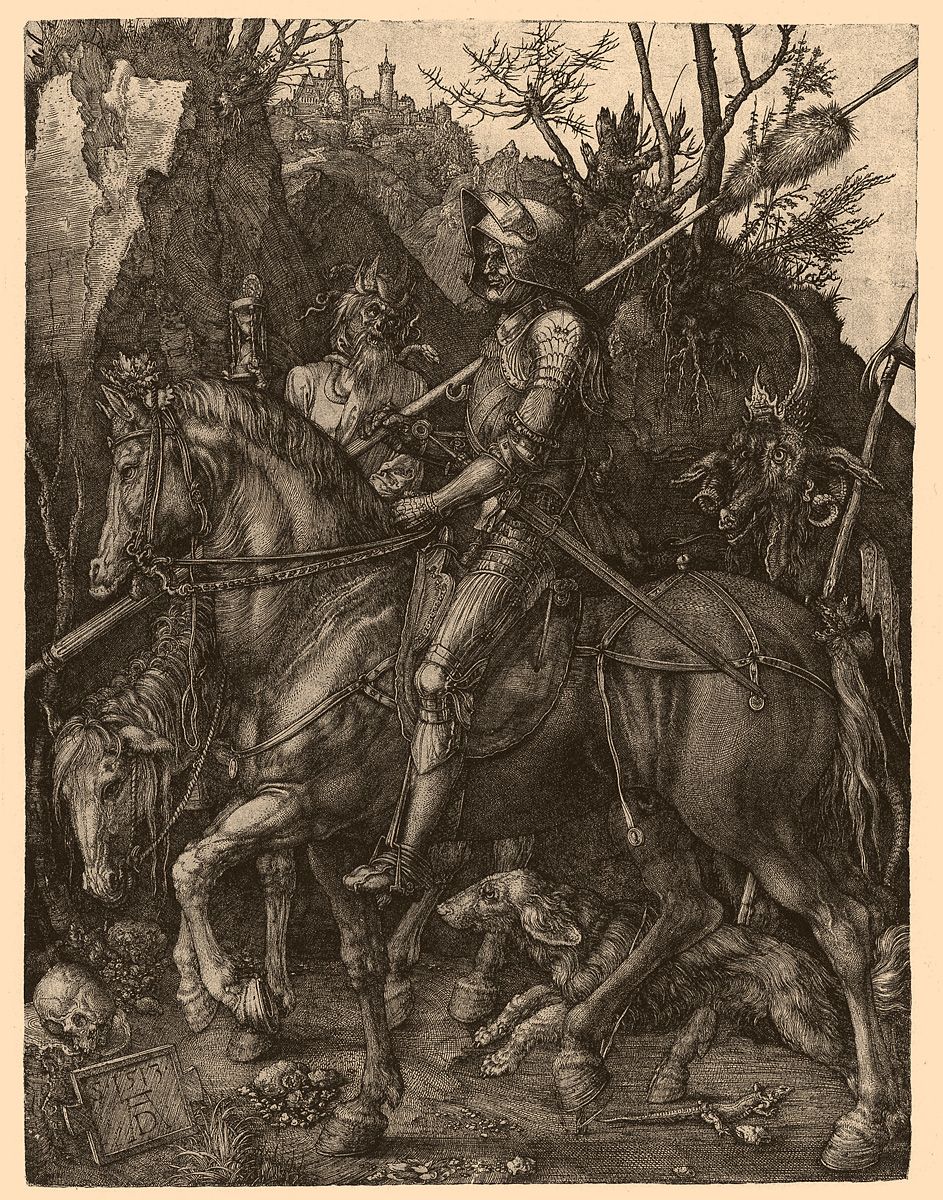

39. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Knight, Death and the Devil. 1513. Signed in monogram, dated and inscribed: S[alus (?)] or [Anno] S[alutis (?)]. Engraving. 244 x 187 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34517; Bartsch 98; Dodgson, A. D. 54; Meder 74 (a), Hollstein 74

The engravings Knight, Death and the Devil (B. 98) dated 1513, and Melancholy, or Melencolia I (B. 74) dated 1514, are two of Dürer’s most famous masterpieces. Knight, Death and the Devil which the author called simply Der Reiter, develops the idea of the inevitability of death, of divine judgment, and the punishment of sins. Associated with this print is a drawing of Death on horseback (British Museum, London), inscribed: Memento mei (Remember me). The obvious affinity of the drawing to the print suggests that the words of the inscription may serve as a key to the proper understanding of Knight, Death and the Devil.

The work is steeped in allegory and symbolism. The connection of the picture with the real world is beyond a doubt, yet we should bear in mind that to Dürer, who was a son of his time, the subject was of importance primarily as a vehicle for the expression of certain theological concepts. In full keeping with the tradition of medieval art, the objects and actions, each of them self-contained, have a metaphorical meaning in addition to their direct sense: the skull is associated with the ideas of death, Original Sin, and the passing of Adam; the dial is an allusion to all-destroying time; the trees, with their broken trunks, suggest by their deadly stillness the inevitable decline and the preordained doom of all things.

It is the metaphorical structure of the print that underlies the build up of the composition. Dry skeletons of trees press upon the Knight on all sides; they seem to hold him captive, barring his progress – as does the stump of a tree, with the skull resting upon it, and as do the dark masses of rock which intervene between him and the wide open space beyond. The print was interpreted by Friedrich Nietzsche as “Dürers Bild von Ritter, Tod und Teufel als Symbol unseres Daseins: unbeirrt und doch hoffnungslos” (Dürer’s picture of the Knight, Death and the Devil as a symbol of our existence, undaunted yet hopeless).

The entire system of imagery shows that the Knight was conceived of as a purely negative character. The semantic context seems to present him not as a victim but rather as an associate of the Devil. Dürer had no liking for the knightage as a body. It is not for nothing that the rider’s pike is adorned with a fox’s tail, the sign of a marauding knight. We can judge of the connotations of the fox’s tail by some of the German prints of Dürer’s day. Thus, the woodcuts Shop of Foxtails (G. 1578) and Foxtail (G. 1165), created c. 1535 by anonymous artists, testify both by their subjects and the accompanying inscriptions to the connection of the motif of foxtail with the ideas of falsehood, hypocrisy, oppression of others, and the use of violence in pursuit of gain.

The dog, which as a symbol of Death often occurs on medieval tombstones, is endowed here with a broader range of associations. It symbolizes subservience to the devil, greed and envy. The lizard is an allegory of dissembling, and a guise adopted by a demon (cf. the relevant passage on Schongauer’s Flight into Egypt, p. 22).

Hans Vogtherr the Younger’s woodcut Death of the Just and the Unjust (G. 1466 and 1467) executed c. 1540 and furnished with explanatory inscriptions, shows the Just attended on his deathbed by an Angel and allegories of Faith, Hope, Love, Gratitude and Peace; and the Unjust, expiring under the eyes of Death (holding a skull and a dial) and of the Devil, i.e. the same characters, with the same accessories, as appear associated with the Knight in Dürer’s print.

The style of Dürer’s Knight, Death and the Devil is distinguished by a truly classical harmony, unity and balance. The central group has a certain sculptural quality which gives it a resemblance to an equestrian statue.

40. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Melancholy (Melancolia I). 1514. Signed in monogram, dated and inscribed: Melencolia I. Engraving. 244 x 190 mm. Provenance: George Steevens; William Windham, 1804; Inv. No. 34511; Bartsch 74; Dodgson, A. D. 73; Meder 75/11 (a), Hollstein 75/II (a)

Melancholy (B. 74), or Melencolia I, as the artist’s inscription reads, was in the words of Vasari one of the prints “che feciono stupire il mondo” (IX, 264): which astounded the world. The generally accepted interpretation of the subject, which connects it with the theory of the Four Temperaments, seems to us erroneous; rather, the word Melancholy should be understood to mean painful thoughts, bitterness of spirit, sorrowful sympathy with the general misery, sorrowful mood. The concept of the work arose from meditations on the transitory nature of earthly existence and from the eschatological belief in the final end of mankind and the world. It is not, however, an expression of man’s horror of the final destruction; death is treated here in the spirit of philosophic contemplation. This attitude reflects the majesty of the man of the Renaissance who, arriving amidst the roar of rushing comets and menaced by apocalyptic prophecies, achieves harmony with the Universe through the cognition of the eternal laws of being. In its spirit, the print marks the boundary of two epochs: it is the last word of the medieval theocentric worldview, and the first word of Renaissance anthropocentricity, regarding man as the ultimate measure of all things. The juxtaposition of two winged figures, one an infant, the other a mature being, symbolizes the brevity of existence which is doomed to end just as fire is doomed to become extinct, the falling comet to disappear, and the rainbow to melt away. Life is but a fleeting moment: this is the meaning of the flitting bat. The hourglass and the bell allude to the fast approaching end of the world, to be followed by Doomsday symbolized by the balance and the millstone which are mentioned in Revelation as having been thrown down from Heaven: objects plain and everyday in form but sacred in their nature. The magic square signifies that all attempts to solve the mysteries of existence otherwise than through the Holy Scriptures are in vain. Worldly activities, allegorically represented by tools of different trades and by the attributes of the sciences and the arts, produce only things that are doomed to destruction; power and wealth, symbolized by the key and the purse, are vanities. The windowless building – a burial vault – is a reminder of ever-present Death. The figure of the dog, which may symbolize Faith, Prophecy or Death, is evidently associated with the latter, to judge by the fact that the animal is shown lying down by the side of a newly-dug grave. The ladder, one of the instruments of the Passion, must also be a reminder of Death, suggesting as it does, the Descent from the Cross; but it may also be associated with the biblical subject of Jacob’s Ladder, and in this case will symbolize a road to Heaven.

The composition abounds in objects of symbolic significance, important for their theological associations. It is interesting to compare Dürer’s sheet and Salvator Rosa’s Humana Fragilitas (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England), very similar to the former in its conception. Salvator Rosa’s work includes a number of symbolic details of the same order: two persons of different age – an infant and a woman; a knife as a symbol of death and parting; a burning fire as a sign of instability; a falling comet as an emblem of momentariness; and a sphere as an allusion to the transience of fortune. What has been left unsaid in Melancholy is plainly expressed in the Humana Fragilitas: in Dürer’s print, the text written by the infant is unreadable; while in the work of the Italian artist, the child’s hand is guided by Death, and the lines read: Conceptio Culpa Nasci Poena Labor Vita Necesse Mori (Conception is sin; birth, pain; life, hard labor; death, inevitable). The figure “I” in Dürer’s inscriptions on the print, Melencolia I, is enigmatic. The key to its meaning may perhaps be found in the idea of the hierarchy of human genius, proposed in De occulta philosophia by Agrippa von Nettesheim, and ultimately going back to Plato. There are, according to him, three orders of geniuses. Geniuses of the first order have their activity in the world of sensuous experience, like artisans or artists; those of the second order are guided by reason, like scientists or statesmen; and those of the third and highest order, by the spirit, like theologians or prophets. Viewed in the light of this classification, Melencolia I with its prevalence of the emblems of the trades, should be regarded as associated with the first order of geniuses. This is, however, no more than a conjecture. Vasari’s interpretation seems to afford some evidence in its favor: he described Dürer’s Melencolia as shown “contutti gl’instrumenti che riducono l’uomo e chiunche gli adoptera a essere malinconico” (IX, 264): with all the instruments which turn a man or anyone who uses them (i.e. craftsmen or artists) into a melancholy being. In his Melancholy, as well as in Knight, Death and the Devil and in some other sheets of that period, Dürer used, as his principal means of building up form, not so much line as a patch consisting of a group of regular hatches. The astonishing wealth of tonal gradations achieved by the use of this device lends great subtlety and precision to his modeling, and enables him to give airiness and depth to his space. Both works are masterpieces of the highest perfection.

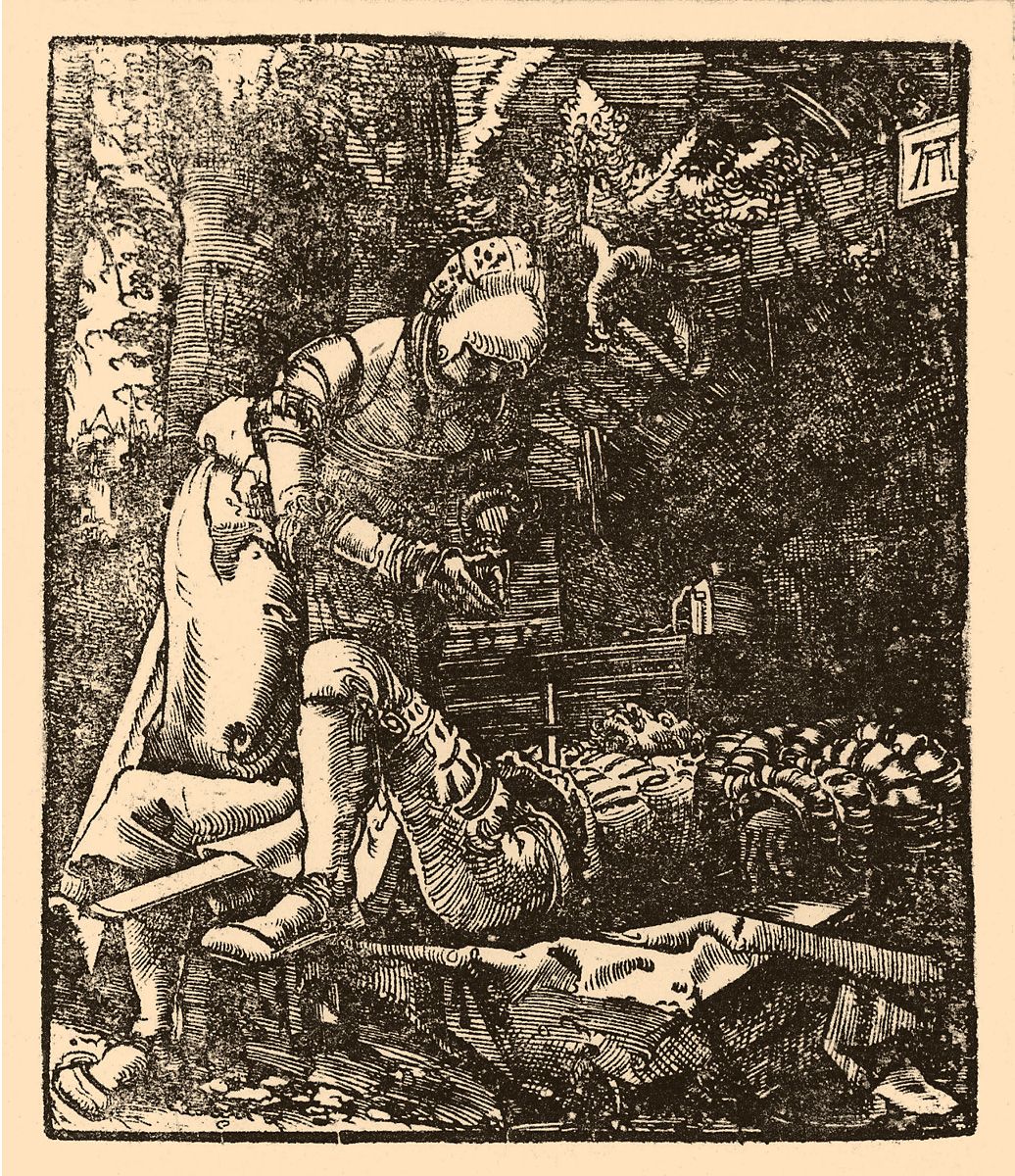

41. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Study of Five Figures (also known as The Desperate Man). C. 1515–16. Etching on iron. 190 x 135 mm; Acquired before 1830; Inv. No. 141863; Bartsch 70; Dodgson, A. D. 80; Meder 95, before the rust; marks (a); Hollstein 95 (a)

The period between the years 1515 and 1518 was marked by Dürer’s first experiments in a new medium, that of etching on iron. Published in this volume is the print of 1515 (B. 70) commonly designated as Study of Five Figures (alternative title, The Desperate Man), which is probably the master’s first venture in this technique. One of the figures has been tentatively defined as a portrait of Dürer’s brother, Andreas. The man in the center has a certain resemblance, perhaps accidental, to Michelangelo. This resemblance has given rise to quite a number of hypotheses concerning the subject of the sheet: it was supposed to re-create some of the characters of the great Italian sculptor, and was even regarded as Melencolia II, intended as a sequel to Melencolia I (B. 74).

There is a free copy (B. 41) of the print, the work of Allaert Claesz, who, in keeping with the Dutch tradition, sought to interpret the subject if not exactly as a genre scene, at least as one with some concrete action. He left out altogether the figure of the man wearing a blouse – the supposed portrait of Dürer’s brother, Andreas – and that of the person resembling Michelangelo. The result was a rather queer composition with a man tearing his hair in desperation and another pouring water from a jug on a naked woman asleep with her hat on.

This attempt of Claesz’s shows with particular clarity that it would be futile to look for a story in Dürer’s sheet. It contains, to all appearances, nothing but a series of preparatory studies for some composition or other; or just chance sketches from life drawn upon the plate as a trial of skill in a new medium.

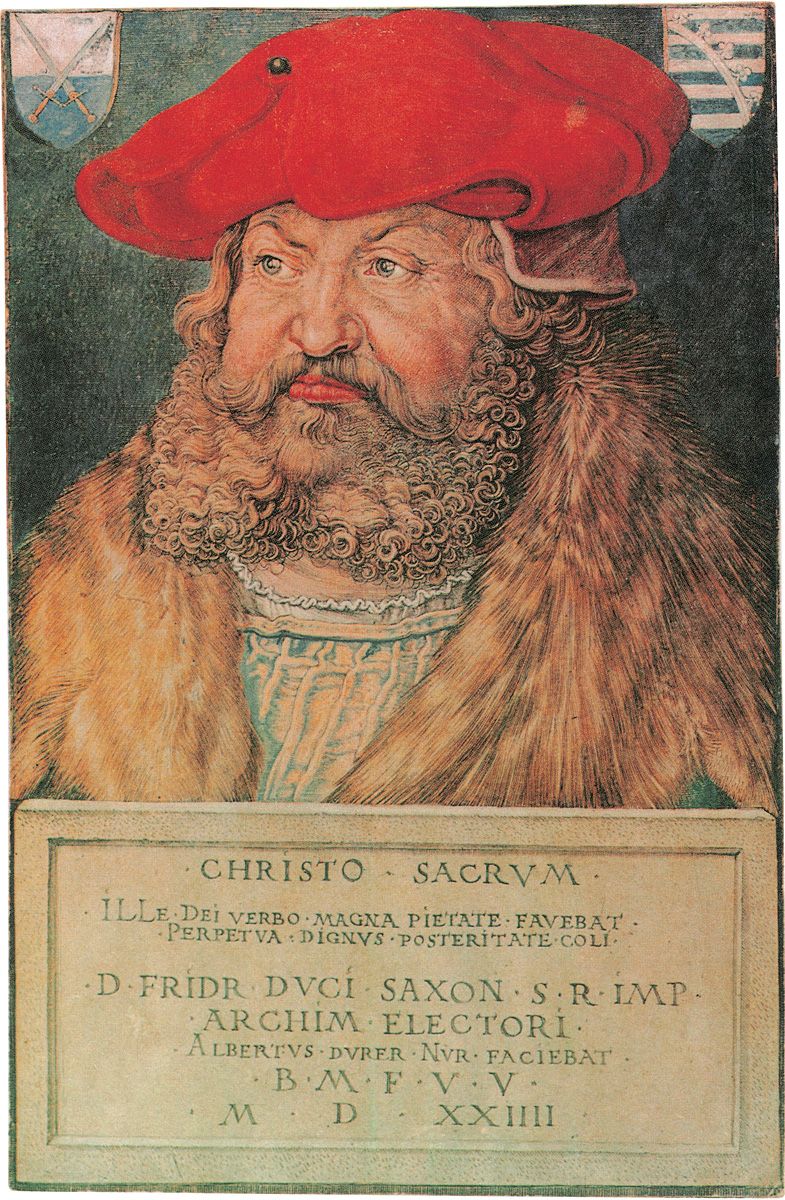

42. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony. 1524. Inscribed: CHRISTO-SACRVM / ILLE.DEI.VERBO. MAGNA.PIETATE.FAVEBAT. / PERPETVA.DIGNVS. POSTERITATE.COLI. / D.FRIDR.DVCI.SAXON.S.R.IMP. / ARCHIM.ELECTORI. / ALBERTVS.DVRER.NVR. FACIEBAT. / B.M.F.V.V. / M.D.XXIII. Engraving. Hand-colored. 191 x 123 mm. Provenance: Baron Adalbert von Lanna (Lugt 2773); Joseph Daniel Bohm (Lugt 271); N. Novopolsky, 1946; Inv. No. 357294; Bartsch 104; Dodgson, A. D. 100; Meder 102; Hollstein 102

Dürer never tinted his prints; yet some colored impressions of his works have come down to us. In these cases the coloring was done by other artists. Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony (B. 104) of 1524, one of the best examples of such practice, is included in this volume. It was tinted in watercolor with great technical competence, probably about the middle of the sixteenth century. Nevertheless, it seems strange that any artist, however high his professional skill, should have had the temerity thus to interfere with one of Dürer’s best sheets. For, by adding color, the illuminator destroyed the precious touch of the master’s hand, impaired the delicate beauty of his hatching, his inimitable tonal gradations; and distorted, perhaps unwittingly, the author’s original conception.

It would be wrong, however, to apply modern standards in addressing this phenomenon: we should rather seek to view it in historical perspective. In the early fifteenth century, after the emergence of printmaking, the art of miniature painting, so widespread during the Middle Ages, perforce gave way to a new art which, having the additional advantage of being able to multiply its productions, could address itself to a broader public. Though miniature painters had the patronage of persons of rank and title, they could not compete with printmakers. We know from Dürer’s own letter to Albrecht von Brandenburg that even such a famous miniaturist and illuminator as Nikolaus Glockendon literally starved, unable to provide for his large family. His trade was not in its former demand, since prints were incomparably cheaper than miniatures. At this juncture, attempts were made to combine the two mutually exclusive arts of miniature painting and printmaking, by introducing the practice of hand-coloring prints; and illuminators began to work in this new field, using the techniques based on those of miniature painting.

In addition to Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, the Hermitage collection includes some other impressions of Dürer’s works, hand-colored in the sixteenth century, such as Melancholy (B. 74) tinted by Monogrammist H. W. G. (Hans Wolf Glaser?). It should be noted that sheets with well-preserved contemporary coloring by skillful masters are a great rarity.

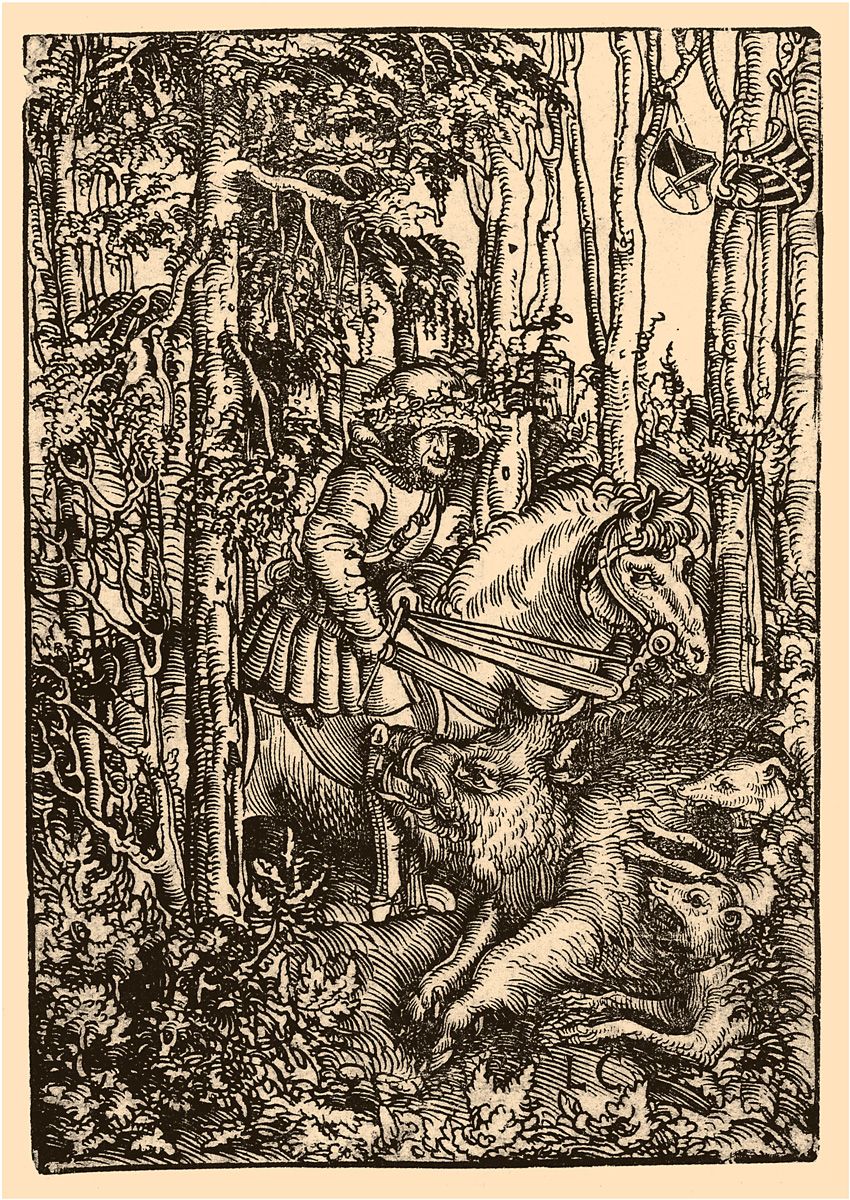

43. Lucas Cranach (1472–1553), Prince on Horseback Hunting a Boar. C. 1506. Signed in monogram. Woodcut. 180 x 125 (cut). Acquired before 1830; Inv. No. 34322; Bartsch 118; Heller 262; Schuchardt 124/II; Dodgson 12; Hollstein 113/II; Geisberg, Woodcut 625; CLB 137

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) was influenced by Dürer in his graphic work, though his artistic personality strongly differed from Dürer’s, even to the extent of being, in certain respects, diametrically opposed to it. Unlike the great Nurembergian master, Cranach did not, in the course of his development, pass from the spiritual elation of his early art to a mood of deep calm and harmonious clarity, but continued, in his mature period, to follow consistently the formulae of his youth. Of great artistic importance are the woodcuts from Cranach’s early period, of which Prince on Horseback Hunting a Boar (B. 118) is an example. To judge by the coats of arms represented in the print, it was created when Cranach was Court Painter to the Elector of Saxony, c. 1506.

The hunting theme had been widely exploited in classical art. On Roman sarcophagi, scenes of patricians fighting wild beasts were common enough. Among the decorations on the Arch of Constantine is a roundel with a boar hunt. Subjects of this description were intended to glorify personal courage as the Roman patrician’s highest virtue. Cranach, too, dealt with a hunting scene as a heroic subject. His knight wears over his hat a wreath of honor: a reward for valor. But Cranach’s interpretation is far removed from the rhetoric of classical Roman art. Like his mythological and biblical characters, so emphatically lifelike – bearded, rough-looking and uncouth in a folky way – so the knightly rider is cumbersome and unwieldy, and makes his way through the thicket in a heavy and laborious manner. In contrast to Dürer, Cranach does not treat his landscape as a mere setting for the figures: they are inseparably linked to form a unified whole, woven into a common pattern by a play of intersecting lines, tense and dynamic, obeying, as it were, a single impulse. Thus does Cranach, by means of his art, assert his ideas against the principles of his great contemporary.

44. Lucas Cranach (1472–1553), Silver Statuette of St. Peter. 1509. XCII from The Large Series of the Wittenberger Heiltums-buch (Book of Wittenberg Sacred Objects). 1509. Woodcut. 128 x 89 mm (cut). Provenance: Johann Martin Friedrich Geissler (Lugt 1072); Board of Exhibitions and Panoramas, 1953; Inv. No. 371774; Bartsch 99; Heller 105; Schuchardt 107 (92); Dodgson 28; Hollstein 96 (92)

The woodcut Silver Statuette of St. Peter (B. 99) was made in 1509 as an illustration for the Wittenberger Heiltumsbuch (Book of Wittenberg Sacred Objects). Cranach’s treatment of the subject is characterized by an expressionist emphasis on the discordant, and by sharp emotional tension. Nor does he use a calm manner in rendering volume, but gives free rein to his ardent temperament: hence the exaggerated movement of forms, and the strong contrasts of light and shade. In portraying the face, Cranach aimed at creating a general impression rather than depicting each individual feature with accuracy. The choice of a popular facial type for the Apostle is readily accounted for by the fact that Cranach’s views closely verged on Protestantism.

Cranach’s watercolor drawing of the Head of St. Christopher (now at the Kunstsammlungen, Weimar), datable to c. 1505, presents an image very similar to that of St. Peter in the woodcut (B. 99).

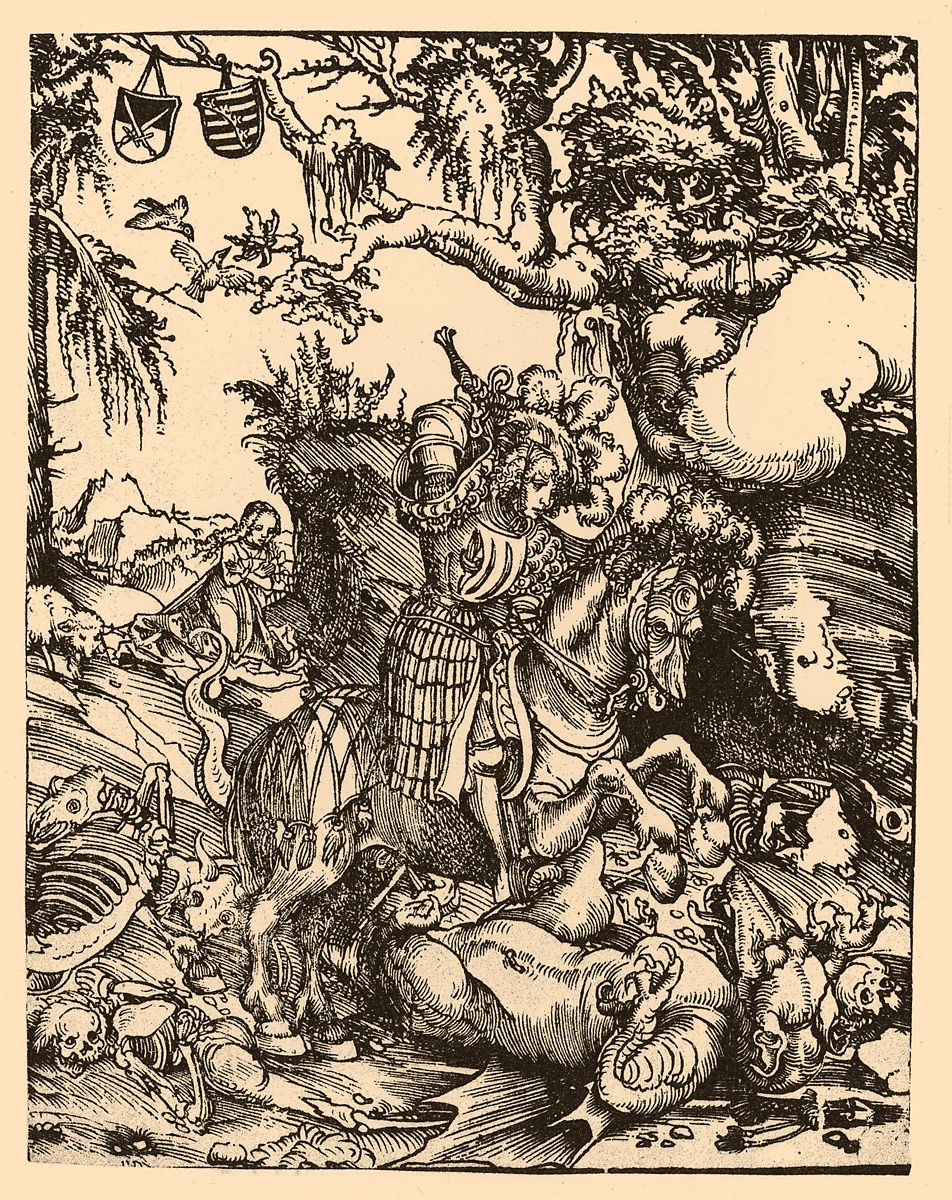

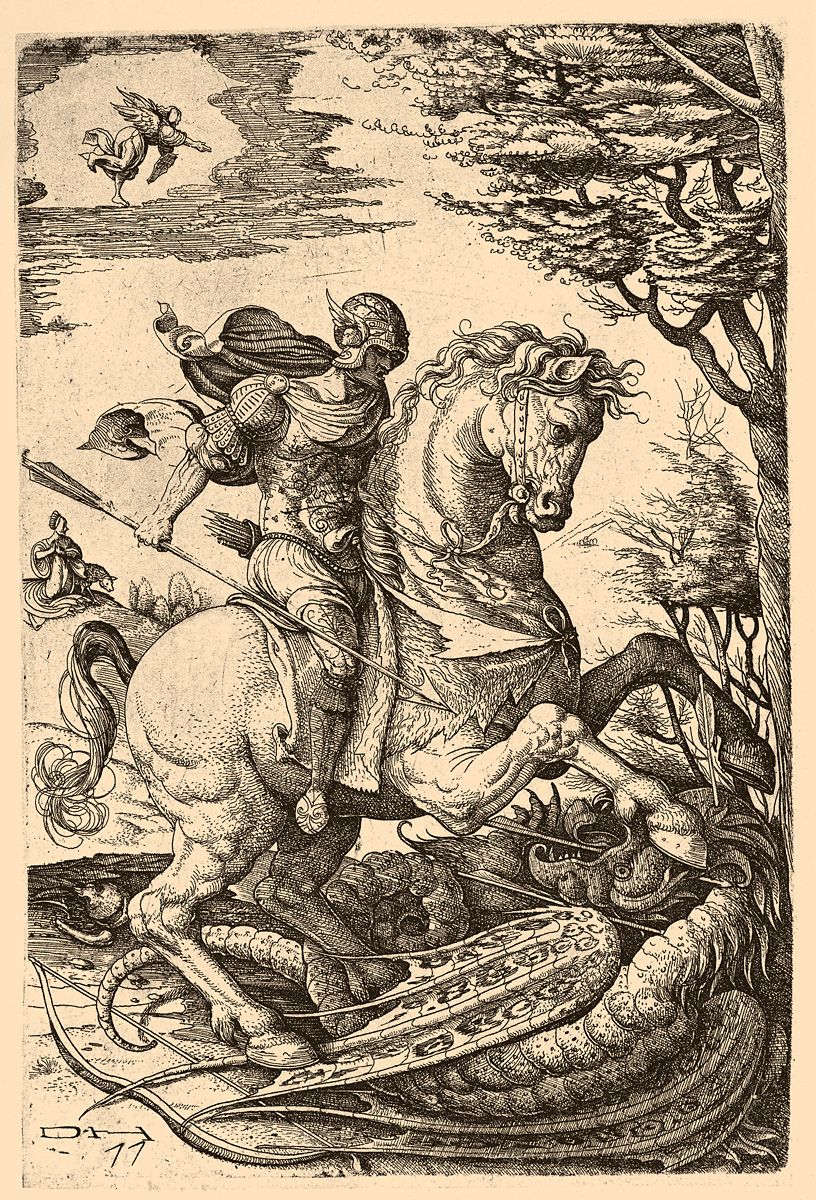

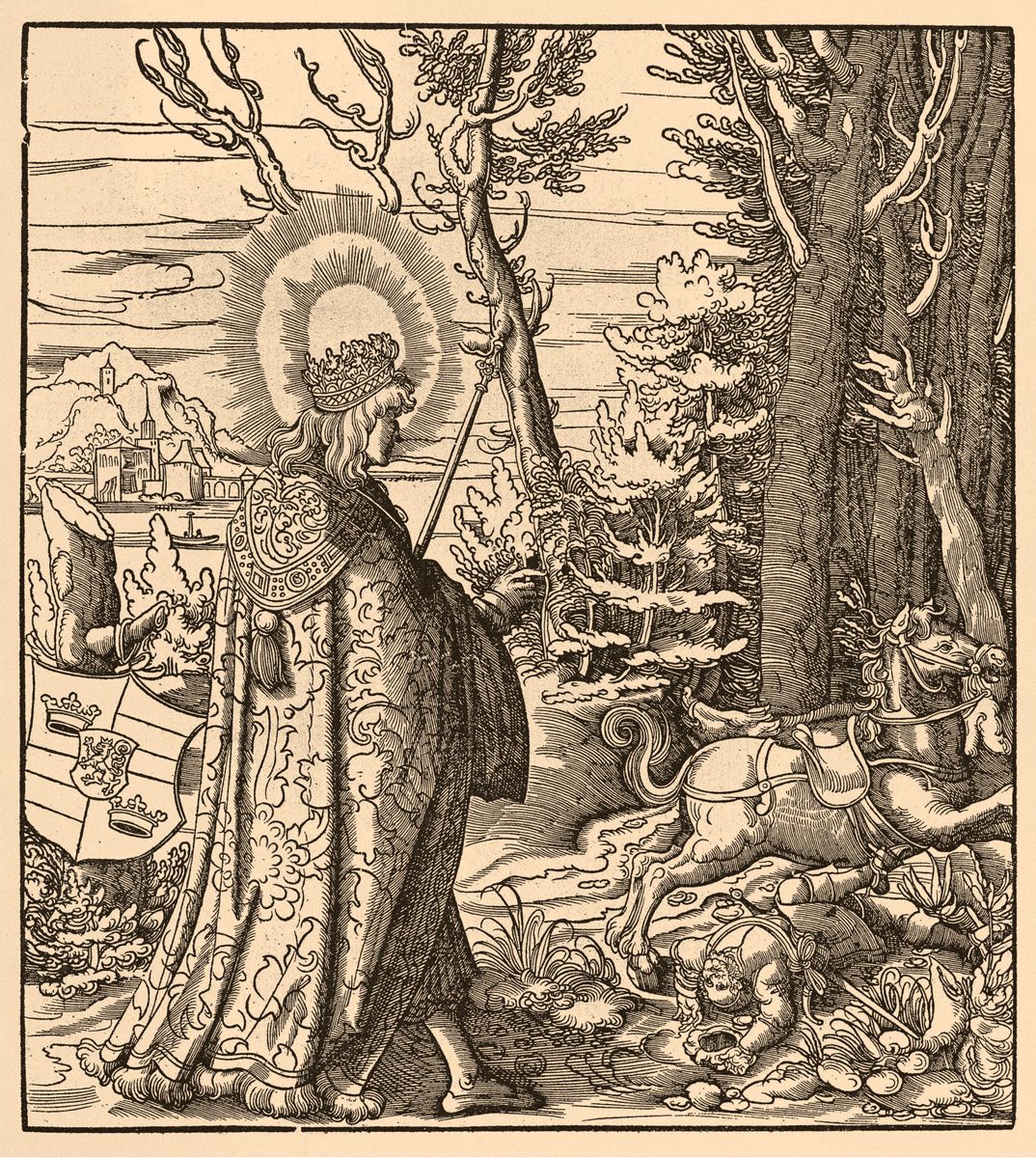

45. Lucas Cranach (1472–1553), St George. C. 1512. Woodcut. 161 x 127 mm. Watermark: Fragments of Gothic p (?). Provenance: Hermitage Library, 1934; Inv. No. 305068; Bartsch 64; Heller 81; Schuchardt 74; Dodgson 90; Hollstein 82; Geisberg, Woodcut 596; CLB 417

The woodcut St. George (B. 64), done somewhat later than either Prince on Horseback Hunting a Boar or Silver Statuette of St. Peter – it was probably created c. 1512 – exemplifies the artist’s search for spatial clarity. A distant view of wooded foothills flooded by the sun, seen in the opening between the branches, strongly attracts the eye. The frank and naïve, almost childish, faith in the truth of the legend is very fascinating. A joyous, triumphant mood, akin to that of a fairy tale, pervades this scene of the handsome young knight rescuing the Cappadocian princess from a dragon. The print was evidently conceived as a pair to Werewulf (B. 115), whose action, showing the cruelty of the monster devouring his victims, is well calculated to induce in the viewer a proper appreciation of the Saint’s deed of valor. The subject of St. George was interpreted as an allegory of the rescue of the Christian Church from paganism and atheism.

46. Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480–1538), Pyramus and Thisbe. 1513. Signed in monogram and dated. Woodcut. 122 x 102 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1804; Count Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Bartsch 61; Winzinger 22 (b); Dodgson 61; Hollstein 76; Kat. Wien 1964, No. 185; Geisberg, Woodcut 41

Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480-1538) was a German engraver of major importance, second, perhaps, only to Dürer. An artist of great refinement, Altdorfer was perfect in bold foreshortening, and in creating unexpected relations between the figures and their setting. And yet his art relies not so much on the formal aspect as on the intense life of the soul, on that powerful inner impulse which controls all outward expression. Altdorfer’s prints, whether executed in the technique of engraving, etching, or woodcut, are built up by the use of light and shade; he knew how to give a pictorial quality to his transitions, sudden as well as gradual, from patches of bright light to areas of the deepest darkness vibrating with subtle reflexes.

Though in his compositions the parts are nearly dissolved in the silvery radiance of the whole, Altdorfer, ever partial to the German tradition of Late Gothic, subconsciously preserved a sense of the individual value of an object as a necessary element of the scene. This is a characteristic which he shares with all German art of the time. The same is true of another feature of his work, the presence of an ethical principle based on Christian ideology. Altdorfer’s work in its entirety presents a wonderful picture of the world, sublime in its poetic content, grandiose in its unity, and glowing with a miraculous mystic light. The book contains three sheets which can give the viewer a fair idea of Altdorfer’s graphic heritage. The woodcut Pyramus and Thisbe (B. 61) of 1513 clearly reveals those tendencies in Altdorfer’s art which were to develop later into the leading principles of the art of the Baroque. Light, penetrating the darkness, sometimes floods the scene, and sometimes loses its brightness in the soft glimmering of the middle tones, rich in pictorial potential. In a way, Altdorfer may be said to have anticipated Rembrandt’s experiments in the use of light and shade. The somber lighting creates a strong dramatic effect. Placing his characters amidst the thick vegetation at Ninus’s tomb, where the lovers were to hold their tryst, in the dense shadow verging on an area of complete darkness, the artist, as it were, brings home to the spectator the tragic meaning of the scene.

The story of Pyramus and Thisbe was known in Altdorfer’s day not only from Ovid’s Metamorphoses; during the Middle Ages, it had been one of the best known and most widespread legends of classical antiquity and, as many such legends, underwent a process of re-interpretation by which it was turned into a religious allegory. It was retold in Ovide moralisé, an anonymous poem published at Bruges in 1484 by Mansion Colard; and included in Gesta Romanorum, a vast collection of short didactic stories from ancient literature, each followed by a moral formulated in terms of Christian ideology. The story of the two lovers of Babylon was construed as prefigurative of the New Testament: Thisbe was supposed to symbolize the human soul, Pyramus, Christ; and the wall dividing them, Original Sin. If we take into consideration that medieval versions of classical subjects invariably provided Christian parallels for all the characters of antique mythology, the allegorical nature of the print will be established beyond a doubt. It is hardly a matter of chance that the figure of Thisbe should recall that of St. Irene bending over St. Sebastian in Altdorfer’s painting of 1518 on the St. Florian Altar (Collegiate Church of St. Florian near Linz), as well as that of one of the mourners in his drawing of The Lamentation on a wooden block of 1512 (Graphische Sammlung, Munich).

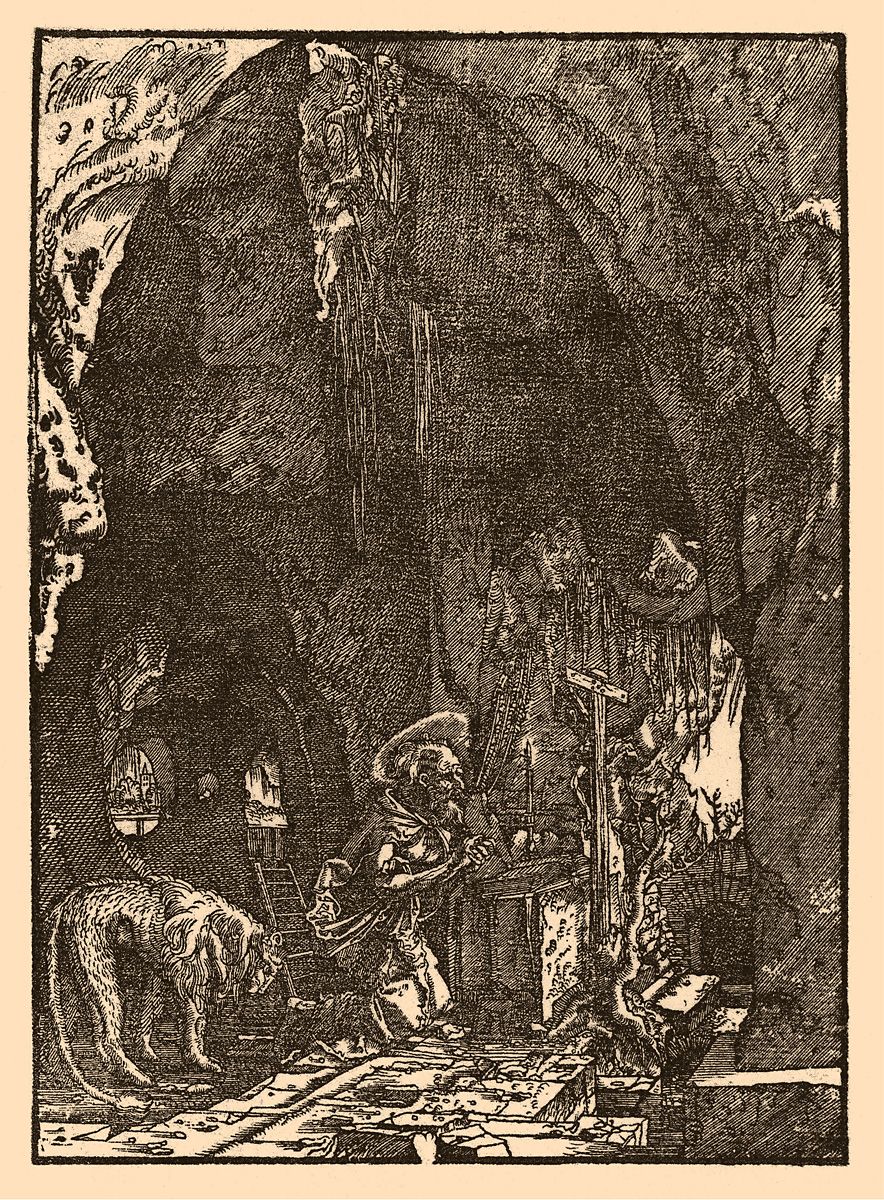

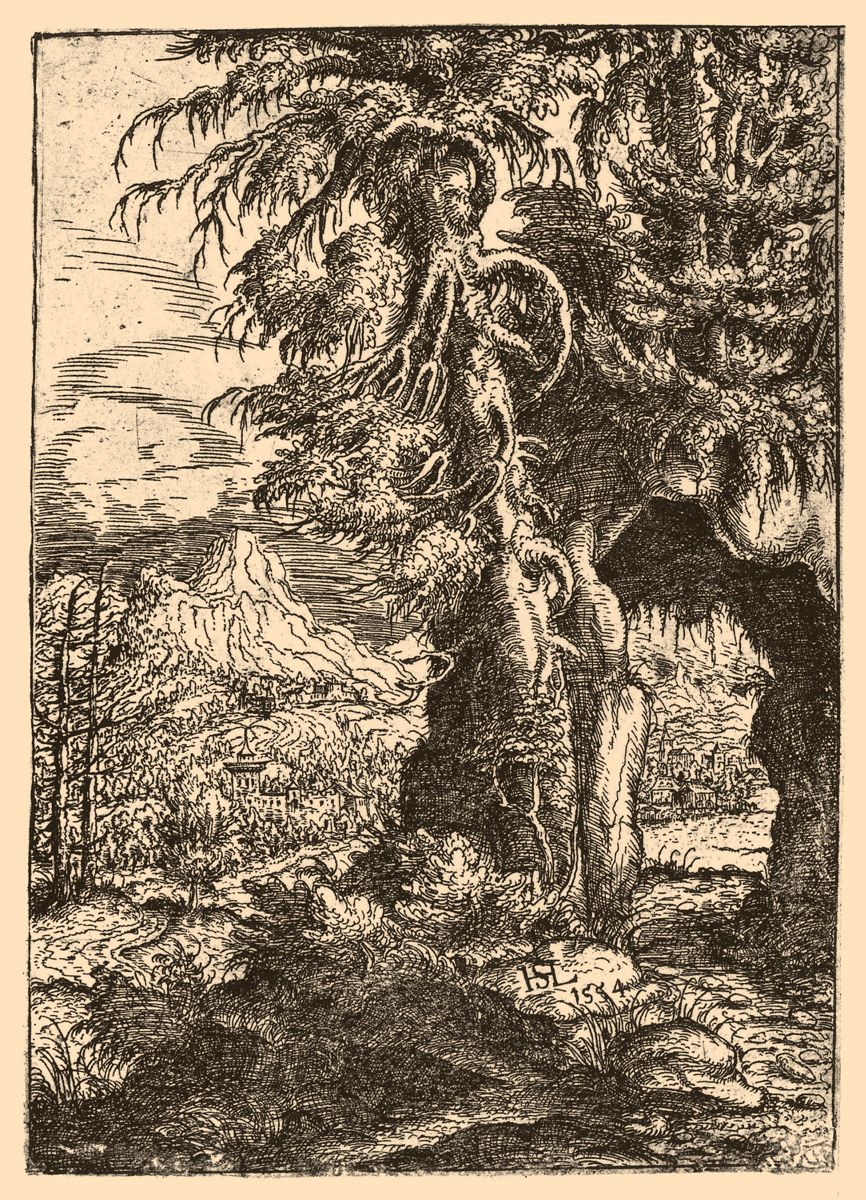

47. Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480–1538), St. Jerome. C. 1513–15. Signed in monogram. Woodcut. 170 x 122 mm. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 141349; Bartsch 57; Winzinger 82 (c or d); Dodgson 58; Hollstein 60; Geisberg, Woodcut 39

The woodcut St. Jerome (B. 57) was created at approximately the same time, c. 1513. The saint is shown at prayer; his figure is expressive of intense devotion and religious ecstasy. The rays penetrating into the grotto from different directions are at once a form of actual atmospheric light, which makes the outlines of the objects stand out against the darkness of the interior, and a mystic radiance suggestive of divine revelation. Like fifteenth-century Ferrarese artists, like Andrea Mantegna and painters of the early Venetian School, Altdorfer contrasts the vitality of man and the lifelessness of the background of cracked rocks, evoking association with the Thebaid.

48. Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480–1538), The Virgin and Child Blessing Nature. C. 1515. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 163 x 117 mm. Watermark: Gothic p with flower. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. No. 151182; Bartsch 17: Winzinger 122 (a); Hollstein 19; Kat. Wien 1964, No. 188

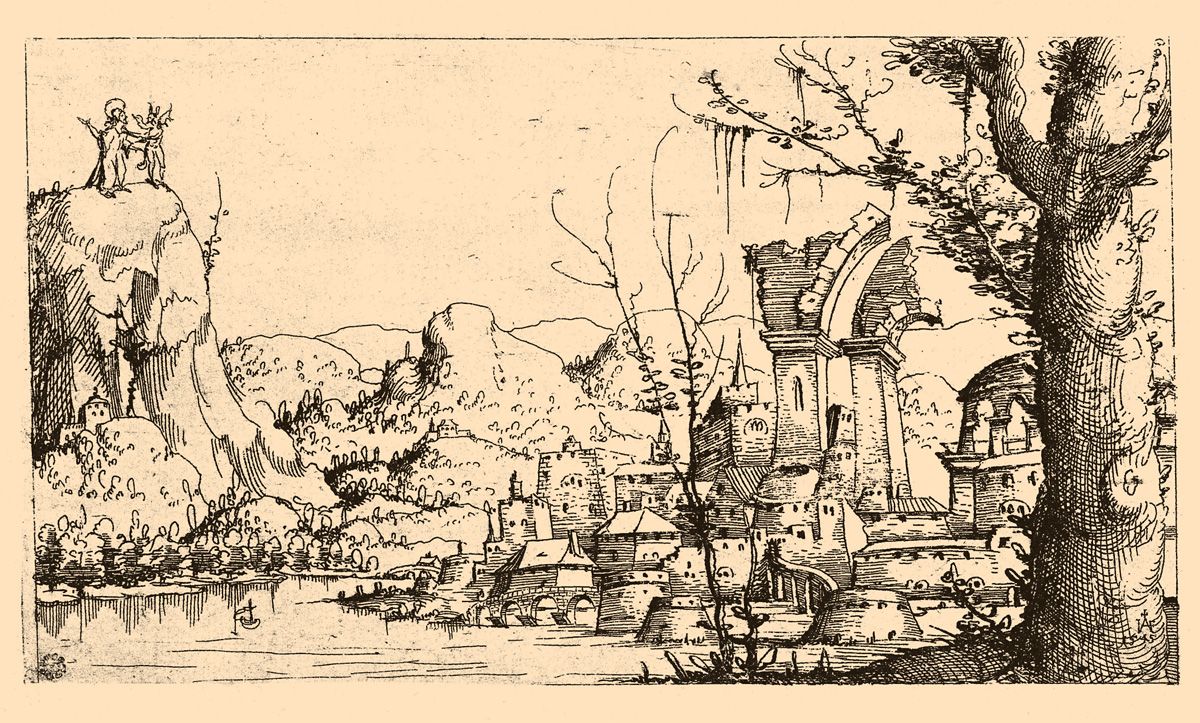

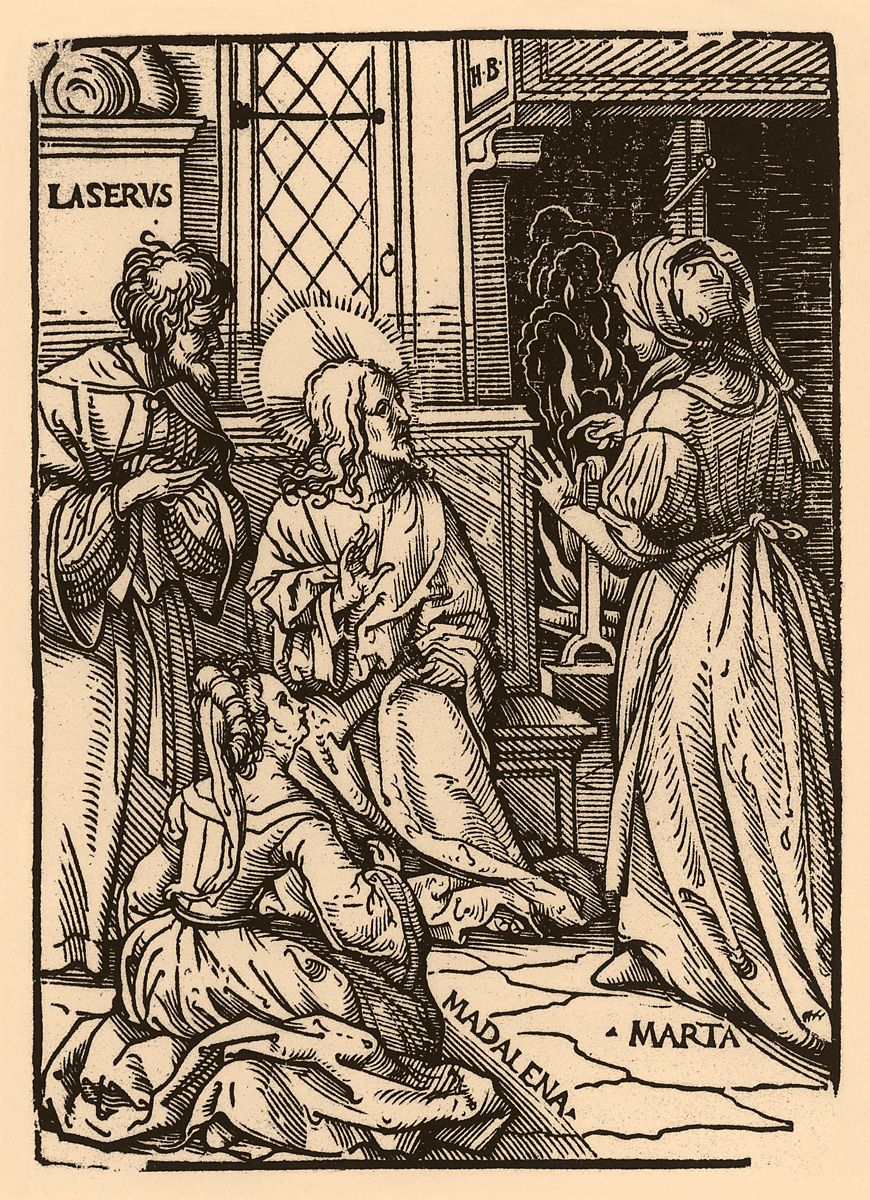

Altdorfer’s familiarity with the art of the Italian Renaissance is also manifest in his engraving of The Virgin and Child Blessing Nature (B. 17), executed c. 1515. The figure of the Virgin recalls that in The Holy Family (H. 4), an engraving by Giovanni Antonio da Brescia. The Madonna with the Child standing on Her lap, His arm raised in a gesture of blessing, was a common subject in the Della Robbia studio, and even more so in that of Andrea Verrocchio. And yet Altdorfer’s version, with its peculiar visionary quality, is very remote from the Italian sources which inspired it. The German engraver depicted a stretch of country with a village and some wooded foothills in the distance. The fir-trees near the figure of Mary form a connecting link between it and the distant view, turning the landscape from a mere background motif into a scene of action. The same unifying purpose is served by the shimmering light enveloping the figures and the landscape; the uneven, pulsating shadows create an illusion of aerial medium. This treatment of light, though anticipatory, in a sense, of the concept developed by the Impressionists of the nineteenth century, is far from being the result of that conscious and attentive observation of nature which is an organic trait of modern art. There is a sense of unreality about it. The Infant Christ, blessing the universe with a gesture of His outstretched hand, indicates thereby His own unity with Nature: this may be regarded as an expression of Altdorfer’s Christian pantheism.