INTRODUCTION

Paris has its own special atmosphere – an atmosphere that every day draws hundreds of thousands of visitors to it from all over the world. No one can be lukewarm about Paris. Of mythical status, the city is so disarmingly seductive that everyone who leaves it always means to return.

The centre of the city bears ample evidence of a past rich in history – a past that is nonetheless perfectly integrated into an urban area in active and constant evolution.

Most radiant of cities, most romantic of cities, Paris is ever ready to lend itself to the heady emotions of admirers who revel in its wonders.

JUST A LITTLE HISTORY ...

Recent excavations in the area of Bercy have brought to light a number of small boats dating from the 5th millennium BC. Much later, in the 5th century BC, the Celtic tribe that was to be known to the Romans as the Parisii occupied the centre of the Paris Basin, a fertile plain irrigated by the River Seine and by several other rivers. Their main settlement was an island in the middle of the southern branch of the Seine – the island now called the Île de la Cité. It was a site chosen for the protection afforded by surrounding hills, but that protection was utterly futile in the face of the barbarian hordes that later raged across the land.

In 52 BC the Romans turfed out the Parisii and took over the Île. The ensuing Gallo-Roman period lasted for close to three centuries. It was a time of peace – the enforced Pax Romana –, which for the township was also a time of prosperity. The Roman administrative authorities were located on the Île de la Cité, while on the Left Bank stood the forum, an amphitheatre, another theatre, and the public baths. The present-day Rue Saint-Jacques corresponds to an ancient Gallo-Roman trackway linking other settlements to the north and south.

The area then became subject to attacks by Germanic barbarians, and a protective embankment was built around the Cité. At the beginning of the 4th century AD, the town – known contemporarily as Lutetia – began instead to be called by the name of its original inhabitants, the civitas Parisiorum (‘the city of the Parisii’), from which Paris takes its modern name.

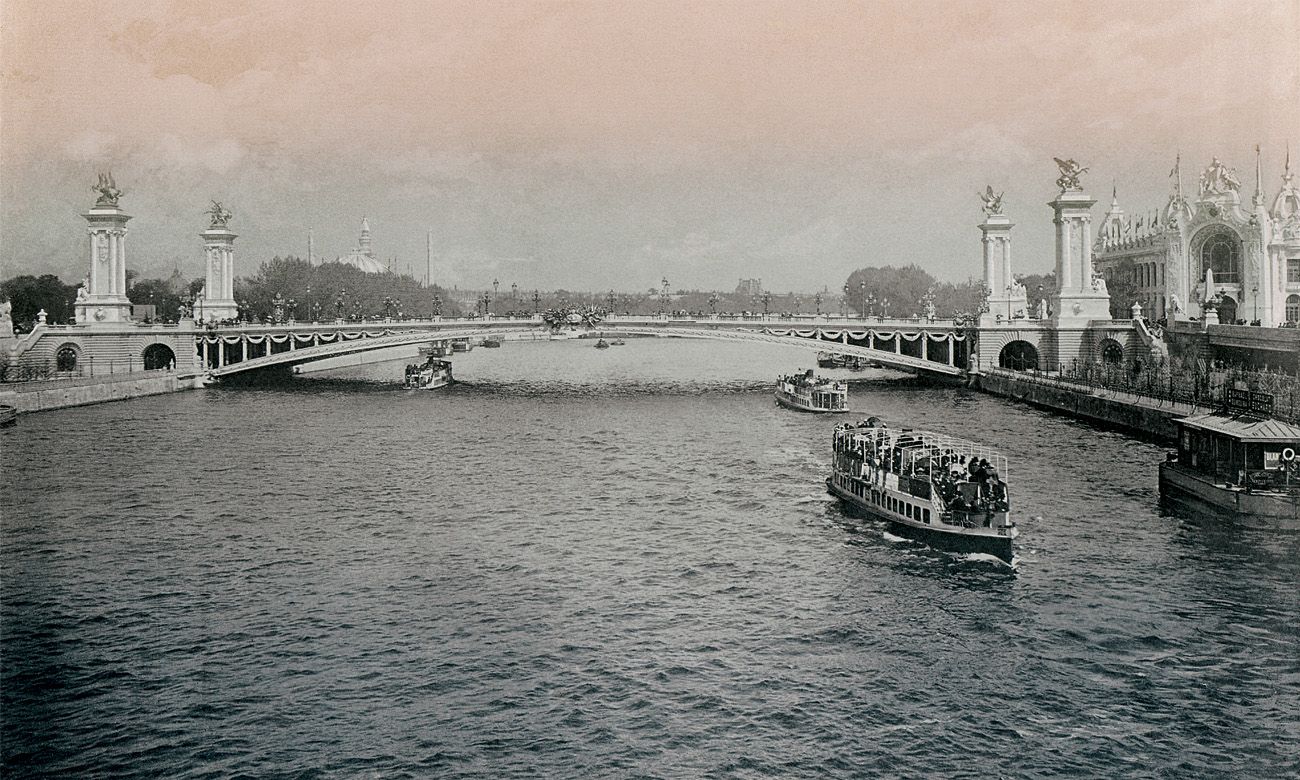

1- April 14th, 1900; inauguration of the Exposition universelle (World’s fair).

Led by Attila, the Huns marched on Paris in 451, but apparently through the prayers of St Genevieve (who thereafter became a patron saint of Paris) were diverted away from the city before they actually got there. In 508 the Merovingian King Clovis made Paris his capital. Many great ecclesiastical buildings – including St Stephen’s cathedral (later to become Notre-Dame) on the Île de la Cité, the basilica of St Denis (Sacré-Cœur) and various other foundations – were constructed, testimony to tremendous religious fervour over the following 500 years; testimony too to enormous economic growth, proof of which is the establishment there of the mint. The city’s population eventually reached 15,000.

Between the 11th and the 13th centuries Paris underwent considerable expansion during something of a Golden Age. After the Cité and the Left Bank, it was the turn of the Right Bank of the river to be developed. The area became the business and financial quarter – as it still is today – in which Jewish and Lombard businessmen were prominent. The increase of water traffic on the river required the development also of port facilities at the Grève, while food supplies for the city were channelled through Les Halles. Marshy areas were drained and brought under cultivation – although the district is still known as the Marais (‘Marsh’).

During the Middle Ages, the population of Paris topped 50,000. King Philip II Augustus, at the end of the 12th century, enhanced the city’s defensive ramparts on both Banks, and set up the fortress that was the Louvre (which he called ‘our tower’). He reorganized the wharves and jetties to accommodate the commercial upsurge on the Seine, and began paving the more frequented streets of Paris. However there was no attempt at hygiene. Raw sewage tossed unceremoniously into the street was removed only by the ordinary rainwater drainage system, making transport on both road and river hazardous in many ways. It was the same all through the 13th century – indeed, in some areas of the capital it was the same right up until the 19th century. The Seine was horribly polluted. Drinking water therefore posed another problem: natural springs had to have pipes fitted to them, wells had to be dug, channelling systems (including aqueducts) had to be constructed, so that the inhabitants could drink safely.

2- The peristyle of the Grand Palais.

3- The Champs-de-Mars.

4- The Pont Alexandre-III.

Paris was governed by a representative of the Crown, the Provost, whose official residence was the Châtelet, and who was in charge of the judiciary. In addition, the civic guild of rivertraders elected their own community representative. Together, these two municipal officers constituted the beginnings of civic authority in Paris. Their official seal – featuring a boat and the motto Fluctuat nec mergitur (‘It floats and is not submerged’) – remains part of the city’s heraldic coat of arms.

On the Île de la Cité, a new cathedral church began to rise as a replacement for the church of St Stephen. It was eventually to become Notre-Dame, but was the first inspiration of Bishop Maurice de Sully in 1163. By 1245 King Louis IX had added the splendidly Gothic Sainte-Chapelle.

The medieval era was marked by the high standards of ecclesiastical learning particularly evident in abbeys and clerical schools, among which was the cathedral school of Notre-Dame. In the 12th century, the schools of the Cité moved on to the Left Bank and was organized into a university, which, from the 13th century, was to be influential all over Europe. To accommodate the scholars and their lecturers, residential colleges were constructed in which lectures could be delivered to the students who lived on the premises. Robert de Sorbon founded such a college in 1253 – from which the name Sorbonne derives. In the 21st century the area is still mostly peopled with university students and is still called the Latin Quarter.

Paris prospered and expanded: soon there were 200,000 citizens. It became the economic, cultural and intellectual capital – but many very serious difficulties then intervened. The Hundred Years’ War, the Black Death (1348–1349), poverty, famine, icy winters and swinging taxes all caused civil unrest. An uprising was led by the merchant guildsman Etienne Marcel, but it was crushed and he was killed in 1358. A revolt finally succeeded in 1418, but led to occupation of the city by Burgundians. Joan of Arc then failed to deliver Paris from Burgundian and English dominance (1429) and was burned at the stake for her pains (1431), although she inspired a new movement for national unity.

Paris was thus depleted of about half its population; those who remained suffered severe poverty. Yet things got even worse. In the time of Charles VII, the royal court moved to Touraine, and although some administrative reorganization took place in Paris, it was the Val de Loire that benefited most. This is where first vestiges of the forthcoming Renaissance were already appearing.

The onset of the Renaissance was given a boost by the invention of the printing press during the 15th century, which rendered the laborious hand copying used up till now unnecessary” In 1530, Francis I founded the College of the King’s Lectors (later the Collège de France), and in 1570 Charles IX founded the first Académie Française.

It was Francis I who decided that Paris should once again act as the seat of royalty in France, although it was his successor Henry II who made a ceremonial entrance into the capital in 1549, to take up residence in the Louvre.

5- General view of Paris.

The 16th century saw the population of Paris grow to around 350,000 inhabitants – which itself caused problems of accommodation and of personal security. In spite of the increase in the number of paved roads, the imposition of systems to regularly collect or clear sewage, as well as an initial attempt to install public street lighting, everyday life in Paris was harsh – drinking-water was still in short and uncertain supply.

Religious strife between Catholics and the Protestant Huguenots came to a head in the terrible slaughter of the Huguenots that came to be known as the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, at the end of August 1572.

It was not until the end of the century and the readmission to Paris of King Henry IV after he had converted to Catholicism that the capital really began to experience more tranquil times.

It was Henry who would leave his mark on the district of the Marais, giving it much of the appearance it has today, with its fine and typically French hôtels. He designed the Place Royale (now the Place des Vosges), the Place Dauphine, and relaid out the Île Saint-Louis. Bridges – including the Pont-Neuf – were built to link the islands with the two Banks. Transport and communications were vastly improved. The Faubourg (suburb) Saint-Germain benefited greatly from it, and expanded in its turn.

Not far from the Tuileries, laid out a generation before by Catherine de Médicis, Cardinal Richelieu – one of Louis XIII’s ministers – constructed the Palais-Cardinal, which he bequeathed to the Crown at his death. It was later to become the Palais-Royal.

Serious economic problems then bedevilled the royal court. Subsequent high levels of taxation poisoned relations between the court and parliament to the extent that there was some civil unrest and the occasional putting up of barricades. However the young Louis XIV managed, in time, to impose his authority. Technically resident in the Louvre, he spent most of his time in Versailles from 1671. It was his intention to expand on Louis XIII’s territory and modernize the city to his own aesthetic tastes. There was to be nighttime street lighting with oil lanterns. The distribution of drinking water was to be upgraded. A fire brigade and a general hospital were to be established, as was a public transportation system. The Place des Victoires and the Place de Louis-le-Grand (now the Place Vendôme) bear witness to the power and the glory of Louis XIV, rightly known then and since as ‘the Sun King’.

From the 16th century on, ladies of culture and refinement in Paris were accustomed to receiving the intelligentsia – notably philosophers and artists – in their literary salons. By the 18th century, such salons were the showpieces of French civilization and the envy of Europe. Foreigners loved to be invited. Casanova, in the 1770s, certainly did. It was in such surroundings (and in more recent institutions like cafés) that the mix and flow of new ideas could be presented which in time would inspire the French Revolution.

A nauseating stench unimaginable to a Parisian of the 21st century plagued the capital. Nonetheless, everyday living conditions gradually got better. The revised layout of the Place Louis-XV (today the Place de la Concorde) enabled the convergence of two major directional routes and the consequent siting of what is now surely the most beautiful avenue in the world: the Champs Elysées. In around the 1770s Philippe, Duke of Orléans, converted the gardens of the Palais-Royal into a profit-making enterprise, installing wooden galleries.

At the end of the 18th century, a circular wall was built around Paris. Known as the wall of the Farmers-General (senior tax officials), it enclosed the area subject to import duties (octrois) and was unpopular, to say the least, with Parisians. In fact, taxes together with political and economic crises, famine, and widespread poverty were sorely trying the people’s patience. Rioting broke out. The storming of the Bastille prison by a howling mob took place on July 14, 1789 – a day now celebrated as a national holiday in France.

The Terror then raged in Paris. The king was guillotined in the Place de la Concorde on January 21, 1793, followed by Queen Marie-Antoinette on October 16th, after several terrifying weeks in the Conciergerie. Nearly 3,000 people were executed in two years. Revolutionary Paris thought nothing of stealing the prized possessions of the Church or of vandalising ecclesiastical buildings, or of looting and torching in general, without fear of consequences in this life or the next.

General Napoleon Bonaparte became the Emperor Napoleon I on December 2, 1804, following his successful campaigns of war across Europe. His many victories in battle had, among other things, furnished the Louvre with a host of priceless works of art. But then came the defeats.

6- The Place de la Bastille and the July Column. This column, measuring 50.52 m in height, dates back to 1883 and commemorates the death of the 504 victims of the July Revolution. Each one of their names is engraved on its bronze shaft.

7- The Arc de Triomphe and the Avenue des Champs Elysées in 1900.

Often absent from Paris on his military adventures, Napoleon determined that the city should become the most beautiful in the world. After a decade of demolition, he oversaw the beginning of important reconstruction work intended to improve the living conditions of all Parisians. There was very little money to spare; yet what he did manage to get done is remarkable, including the arcades of the Rue de Rivoli, some new bridges, the Place de la Bastille and the canal Bassin de la Villette. He also ordered the erection of the triumphal arches of the Etoile and of the Carrousel.

Paris experienced days of serious civil unrest in 1830, and then again in 1848. From 1830, the city underwent a process of transformation through rapid industrialization. A network of rail services was inaugurated, and many stations built (1835–1848).

The 19th century was another era of change for the capital. Water was piped into the houses, drains were laid that really did what they were supposed to, communal transportation systems forked in all directions, gas lighting became widespread. By 1850, the city could count around one million inhabitants. Baron Georges Haussmann – Prefect of the Seine under Emperor Napoleon III for nigh on twenty years (1853–1870) – completely changed the look of Paris by demolishing swathes of substandard housing to build great arterial thoroughfares from which fine views of the city were visible. Haussman has rightly been described as ‘the creator of modern Paris’. At the same time he could be said to have broken up the city’s overall unity. It was in 1860 that Paris was divided into 20 arrondissements.

Society in 19th-century Paris was riddled with inequalities. On the one hand were the working-class poor, subject to innumerable diseases and disorders (notably cholera and tuberculosis) and largely hooked on alcohol. On the other was the bourgeoisie – actively seeking amusing (and preferably licentious) ways to spend all its money.

The second half of the 19th century was the era of the great expositions universelles, the ‘World’s Fairs’, of fashionable society in unprecedented turmoil, and of the creation of the large department stores that sounded the death-knell of the ‘pavement arcades’, typically Parisian commercial and artistic meeting-places since the beginning of the century.

In 1870 Paris was besieged by German forces, to which it capitulated on March 1, 1871. Its disillusioned citizens reacted with riots and arson attacks. The Hôtel de Ville, the Palais de Justice, the Tuileries, the Palais-Royal and various other prominent premises were destroyed. The Paris Commune saw thousands of fatalities, and for some years the city was no longer capital of the country. Political life was poisoned by scandals and disgrace (the Dreyfus affair, Panama, etc.).

Yet Paris was to emerge at the end of the 19th century, perhaps surpri singly, with much to be proud of – the Eiffel Tower, the metro, electrically powered trams, and the motorcar.

The first years of the 20th century are those known collectively in French as the Belle Epoque, a time renowned for the vigor of its cultural and artistic prowess. It was also a time in which the art-inspired architect Hector Guimard put his own imprint on Paris by imposing Art Nouveau forms (involving curves, and asymmetrical and exaggerated details) in place of the former coldly austere style of Baron Haussmann. His sensuous and harmonious style lit a flame that continued to burn, for architects after him (Le Corbusier, Mallet-Stevens and others) tended to concentrate on cubic and rhomboid shapes. Guimard is celebrated for his subway entrances, works of acknowledged genius. French painting meanwhile displayed its explosive vitality in the works of the Impressionists and the Fauves. Artists congregated mostly in the ‘villages’ of first Montmartre and then Montparnasse. Literature flourished. The ballets russes under Diaghilev also saw worldwide fame and success.

The aftermath in Paris of the First World War (1914–1918) was a regrettable state of lethargy that nullified the enthusiasm for modernization originally inculcated by Baron Haussmann. Now with nearly three million citizens, Paris experienced a serious shortage of living accommodation leading to misery for many – and this at exactly the same time (the interwar years) as a rich minority was swanning around in insouciant opulence.

8- View of Paris with the cathedral of Notre-Dame, situated on the island of the Cité, and the Conciergerie.

9- The metro station Abbesses in the Art Nouveau style. The glass panel of this station has been perfectly conserved.

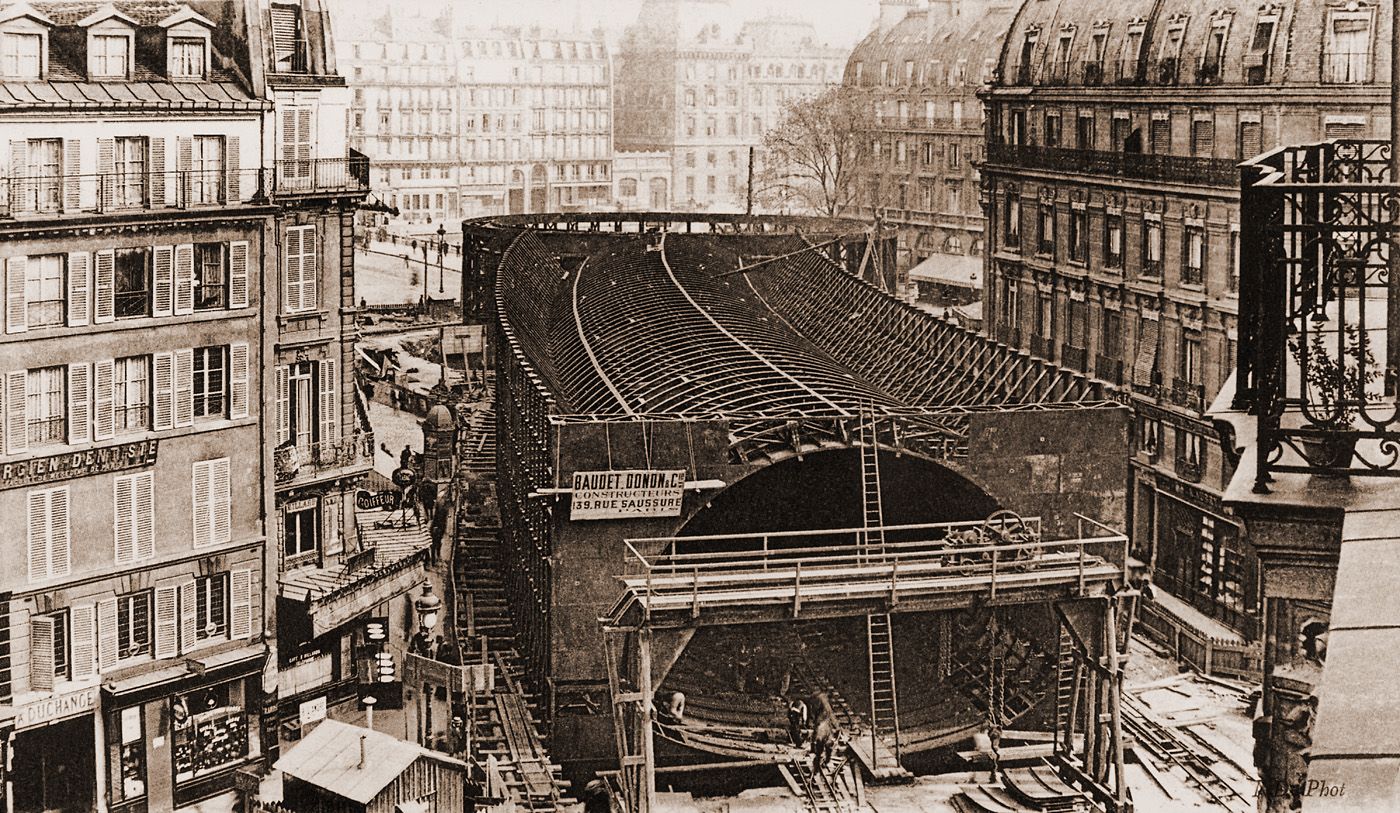

10- Renovation of the metropolitan train tracks near the Boulevard Saint- André, between 1900 and 1910.

The Second World War (for the French, 1939–1944) to many Parisians was something of a ‘phoney war’. Life went on, albeit at a slower pace, with rationing-slips, bribery and corruption, black marketeering, the Resistance and its activities, and the persecution of the Jews. The capital was liberated from the Germans on August 25, 1944, without having suffered the slightest damage. To pick itself up after such years of depression, however, Paris then deafened and dazzled. This was the time of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Boris Vian and Juliette Greco. Radio, cinema, and finally television enabled everyone to know what was going on all the time.

Yet Paris had hardly changed since the time of the Commune (1871), or since Baron Haussmann’s reorganizations. Some years after the end of the Second World War, the consumer society exploded into being, and Charles de Gaulle (considered by many to have been the liberator of France in 1944) instituted the Fifth Republic in September 1958.

Despite the huge difficulties involved in the dissolution of the French colonial empire, the Ministry of Works in 1965 published an outline plan for the city of Paris in the year 2000. Vast building-sites sprang up everywhere, linked by an intricate network of transportation systems right across Paris and its suburbs.

The old market booths (les halles) were transferred to Rungis, a suburb to the south of Paris. For a number of years there was nothing but an enormous hole in the ground – until a new area of development, Les Halles, rose up from the earth together with the Georges Pompidou Centre of modern art (called the Beaubourg by the locals) in 1976.

It was thus in the second half of the 20th century that significant progress was made in improving the living conditions and the overall appearance of the capital. Renovation work then undertaken, including gigantic residential housing schemes (at Les Halles, Maine-Montparnasse and Bercy), virtually reshaped the capital and brought more of a balance between east and west. André Malraux, Minister for Cultural Affairs under President de Gaulle, decided to thoroughly refurbish Paris once and for all. His efforts towards sprucing the place up have lent the city a new lightness and cleanliness.

François Mitterand, elected President in May 1981, was a bit of a maniac for large-scale operations. Colossal expenditure was underwritten. Each new project presented special challenges in its accomplishment. The columns of Buren and the pyramid at the Louvre have since become very much part of the capital. But let’s reserve judgement on the enormous cube that is the Grande Arche de la Défense (which is really nothing special, other than that it follows in the long line that also features the pyramid by the Tuileries, and the obelisk at the Place de la Concorde, the Champs Elysées and the triumphal arch of the Etoile). But we should also thank Mitterand for the renovation of the Louvre museum, which is now one of the greatest museums in the world.

The economic crisis that occurred in the 1990s slowed the frenetic pace of such operations. Most recently, the Museum of Asiatic Arts (the Guimet Museum) has just reopened after several years of closure. Due to open in 2004 is a new museum, the Musée des Arts Premiers, founded by President Jacques Chirac.

Paris, capital of France, if anything, seems a little lost within the immense urban area that is Greater Paris. Every year it attracts millions of tourists from abroad who find in it much to enjoy and much to remember. The city really does cast a spell on those who come from afar and who like diving into history, but it certainly does not rely on tourists to survive. Yet it remains a particularly expensive place to live, and the population has been progressively decreasing (from three million in 1950 to two million now). It might seem to have lost something of itself with them, but look closely, and each of the current 80 quartiers of Paris has its own special spark of vitality.

From its first beginnings, Paris has renewed itself through constantly taking in new residents, first from the provinces, and later from farther afield.

Most radiant of cities, most mystical of cities, most romantic of cities with the Seine and its bridges … City of a thousand fantasies involving les petites femmes de Pigalle … Paris has many hidden corners and private hideaways unknown even to many Parisians.

Paris is essentially a place that mushroomed in the 19th century as a result of the Industrial Revolution. For the most part it is comparatively modern then, except for its historic core and the various traces of Gaullist and medieval times. It has never allowed itself to be entirely consumed by business interests. There are still some vestiges of Italian influence, of the Classical era, and of the century of the Enlightenment – when the whole of Europe spoke French. Such diverse influences still have a role to play in the ‘art’ of living in Paris. The Parisian woman stands out among others for her allure, her stylishness, her light-hearted ebullience and her spiritedly free speech.

Paris is likewise a free spirit, a breath of freedom blowing over it, with its rioting, its students’ revolt of May 1968, its recurrent strikes. The city’s very diversity makes it difficult to pin down.

Throughout the world, Paris represents style and luxurious elegance. It is the capital of haute couture (despite a certain amount of competition from across the Alps and across the Atlantic); it is in Paris that the best artisans – the ones from whom the couturiers constantly demand the impossible – live and work.

To discover the real Paris is not easy for a stranger to the city. There is just too much to see – museums, different areas of the city, and historical monuments. Be guided by your instincts. Take your time. Go places, stop and look at things, try to sense the special atmosphere of the capital. One life is simply too short to take it all in at once.

11- Jacques-Louis David, Bonaparte crossing the Alps at the Mont Saint Bernard, 1800-1801. Oil on canvas, 271 x 232 cm. National Museum of the Château de Malmaison, Rueil- Malmaison.