Cubism

1907-1914

After being impressed with the almond-shaped eyes and elongated, egg-shaped faces of African masks, Picasso returned to a recent work and repainted the faces of its five figures. The blend of the mask shapes with his desire to reduce visual realities to abstract forms and to simultaneously show multiple points of view resulted in this breakthrough work that moved the artist from his African period to Cubism. The challenge of evolving this new art form would possess the artist for several years of his long life. The landscapes of Cézanne, as well as his Bathers, influenced Picasso’s representation of the jagged planes of the work so as to give the figures continual motion. The ‘Avignon’ mentioned in the title refers to a street in Barcelona’s commercial sex district. The faces of the women (especially the two on the right) are also clearly inspired by African art. The exhibition of ‘art nègre’ given in Paris in 1906 had a great impact on the artist. Initially, Picasso had depicted men (sailors and students) in his preliminary drawings (vol. 1, p. 94). He later excluded them so that it is the spectator who becomes the intruder in the scene.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907. Oil on canvas, 243.9 x 233.7 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

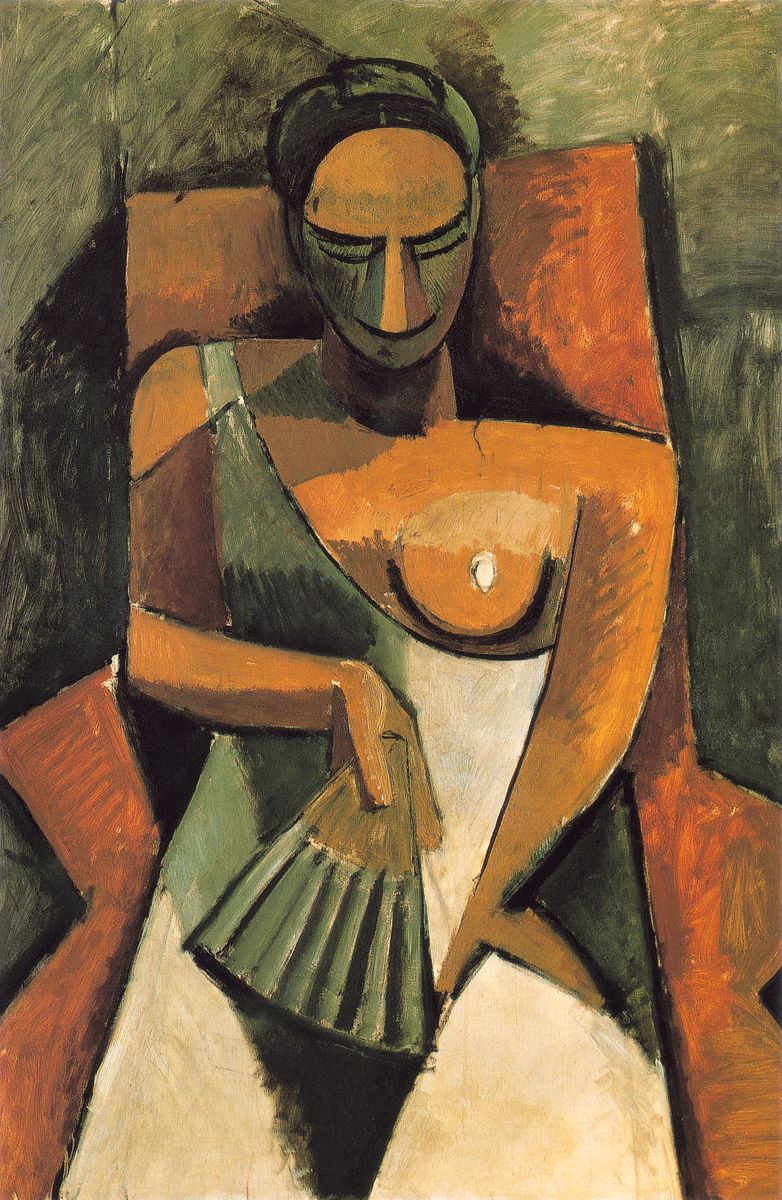

This painting is a great example of Picasso’s rapid shift towards Analytical Cubism. Picasso makes a clear statement of his aim to break away from traditional pictorial representation. Unique, central perspective has disappeared; we now have various, simultaneous points of view. The seated woman, which still derives from African and Iberian sculpture, is presented to us in what at first seems to be a front view. Little must we look, though, to discover that there are various perspectives converging on one same plane. For instance, we see the woman’s left breast from the front, but this contrasts with her face, which can be seen from a bird’s-eye view. This process would become evermore complex as Picasso, along with Georges Braque (see vol. 1, p. 155 and p. 162), developed Analytical Cubism throughout the following years.

Bread and Fruit Dish on a Table, 1908-1909. Oil on canvas, 163.7 x 132.1 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel

In his first approaches to what would later be called ‘Cubism’, Picasso clearly shows the way towards a completely new conception of space. As in Woman with a Fan, Picasso shows us various points of view simultaneously. That is what enables us, for example, to see a frontal view of the upturned cup and, at the same time, the fruit dish from above.

On returning to Paris after spending the summer of 1909 at Horta de Ebro, where Picasso produced some of his classical analytical cubist paintings, he turned to sculpture. He made a portrait of his lover, Fernande Olivier, in a likewise-analytical manner. Without violating the traditional principle of the integrated sculptural mass, Picasso models the surface in a series of spectacular slanted planes; these powerful muscular accents at the constructive joints create an interplay of rhythms, but they also rip open the epidermis of the sculptural surface. Recalling Head of a Woman decades later, Picasso would say: “I thought that the curves you see on the surface should continue into the interior. I had the idea of doing them in wire.” (See a sketch for this work in vol. 1, p. 148).

Houses on the Hill, Horta de Ebro, 1909Oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm. Museum Berggruen, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

Picasso and his lover Fernande Olivier spent the summer of 1909 in Horta de Ebro. It was a place where he had spent one of the happiest moments of his youth (“Everything I know I learned in Horta,” he once said). Here, Picasso continues his deconstruction of perspective. His admiration for Cézanne’s landscapes, which is clearly visible, is taken one step further. The houses on the hill have become extremely simplified geometrical forms, seen from various perspectives at once. Even the sky is seen in various facets.

When tracing the history of modern art, Ambroise Vollard is a capital figure. He was one of the most important art dealers of the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. He championed figures such as Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin, as well as Picasso and other artists of his generation like André Derain and Georges Rouault. This portrait of Vollard is one of the best paintings of Picasso’s analytical phase. Perspective has by this time been completely shattered, and only by details can the viewer bring the pieces together in order to understand that what we are looking at is a portrait. Despite its extremely intellectual approach, Picasso nonetheless manages to convey a vivid representation of Vollard.

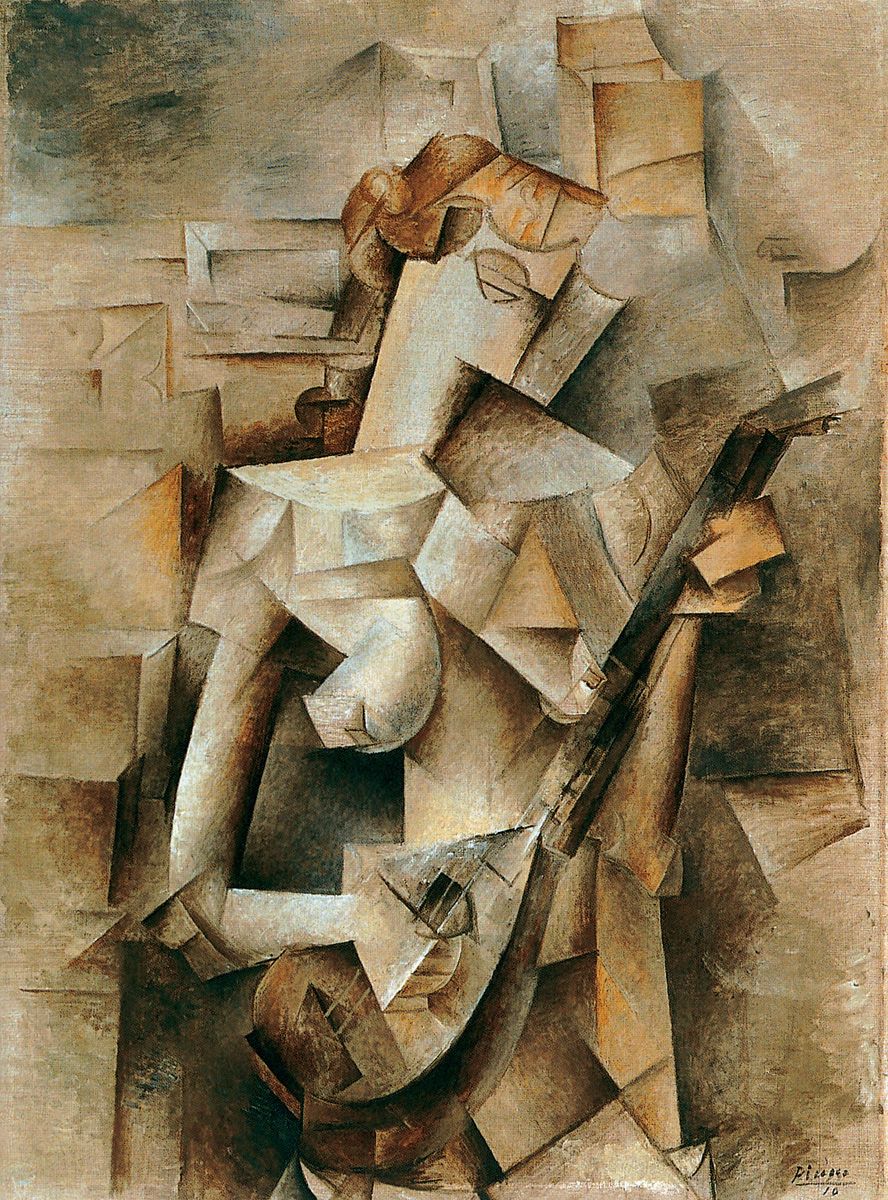

Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier), 1910 . Oil on canvas, 100.3 x 73.6 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The theme of a woman playing the mandolin had been used by Picasso in his investigations leading to Cubism (see vol. 1, p. 144). As in the portrait of Ambroise Vollard, Picasso’s subjects for his first analytical cubist paintings remain identifiable despite the countless facets into which perspective has been broken. Throughout the development of his analytical phase, though, the work of both Picasso and Braque would become almost abstract. So closely they worked together on the further development of Cubism and so hermetic their paintings became, that in some cases even they had problems distinguishing each other’s work (see vol.1, pp. 154-155 and pp. 162-163).

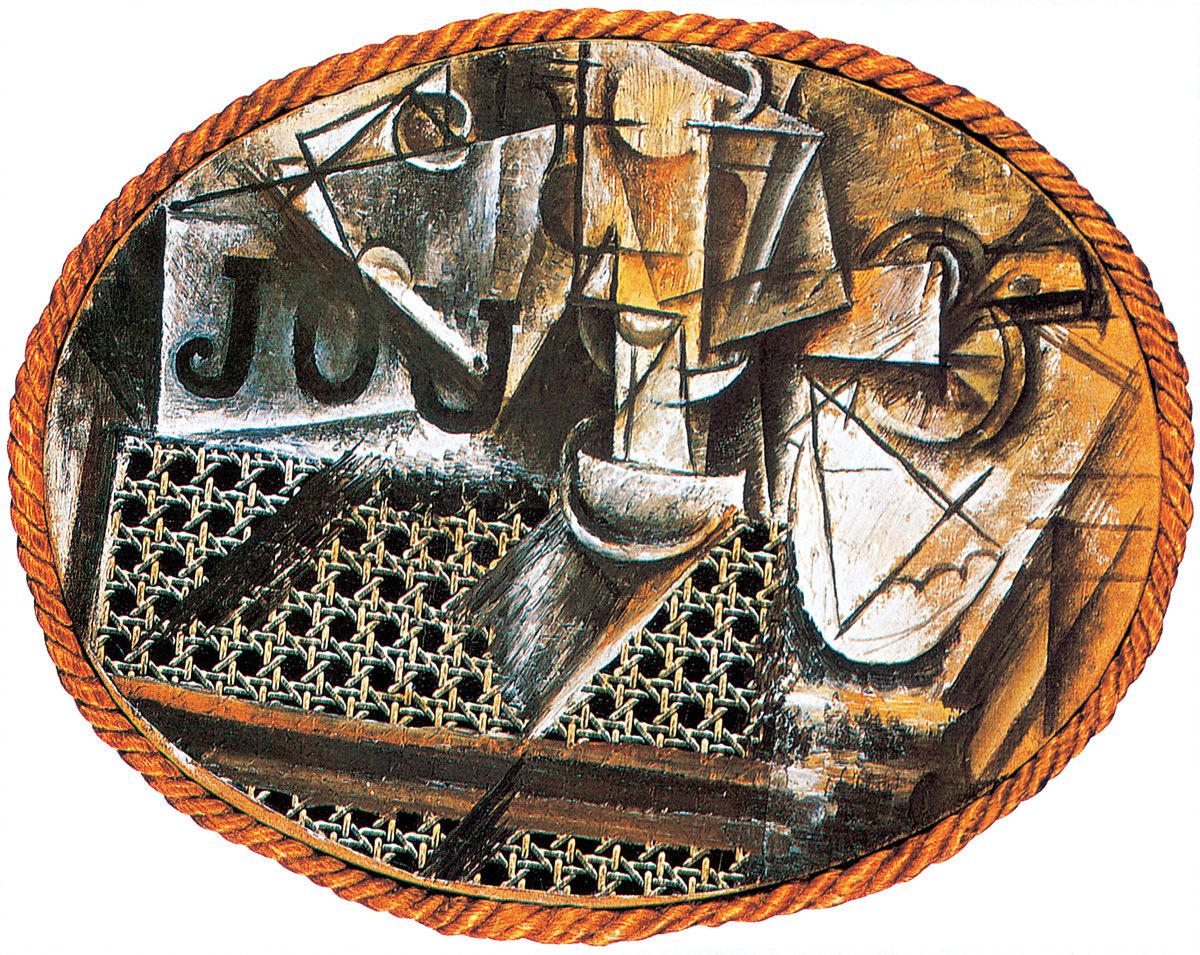

Still Life with Chair Caning, 1912. Oil and oilcloth on canvas framed with rope, 29 x 37 cm. Musée Picasso Paris, Paris

This work marks not only the beginning of Synthetic Cubism, but is also the first example of a technique that would thereafter become commonplace in modern art: collage. Synthetic Cubism was a drastic shift from late Analytical – sometimes called Hermetic – Cubism, which was running the risk of becoming pure abstraction, something Picasso wanted to avoid. In Still Life with Chair Caning, he made a jump back to reality in the most literal sense: Picasso applied onto the canvas a piece of oil-cloth printed with an illusionistic chair-caning pattern. In doing so, he was incorporating a pre-existing object and making it a part of his own work. The letters spelling “JOU” could be a fragment of the word journal (newspaper) but also of the verb jouer (to play), as if Picasso were approaching this landmark artwork as pure child’s play.

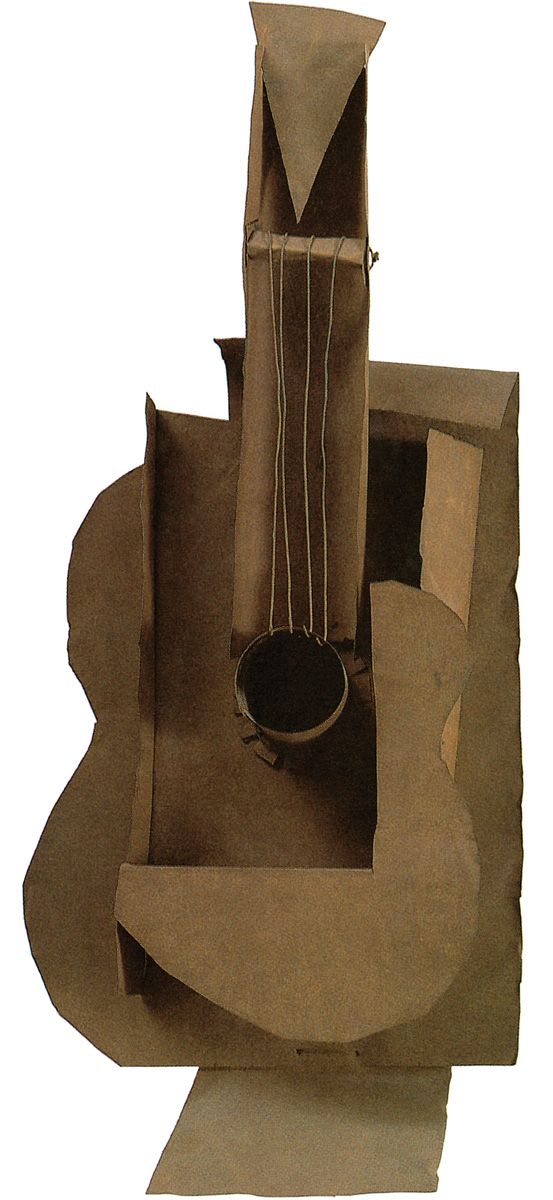

Synthetic Cubism was a period that transformed more than just painting through the invention of collage. From 1912, Picasso made several Guitars that radically changed the idea of sculpture. To create them, Picasso did not sculpt them in a traditional manner. He neither carved nor modelled them, but used a new technique of assemblage. The first versions of this theme (see vol. 1, p. 167) were made out of pieces of cardboard. He would later use sheet metal for the body of the guitar and wires for the strings. Instead of the traditional and noble marble, wood or bronze, Picasso turned to commonplace materials, a decision which is as modern as the fact that the volume of the guitar is not depicted in three dimensions, but suggested through various planes. All modem sculpture is in some way in debt to Picasso’s Guitars.

Inspired by Braque’s first papier collés (see vol. 1, p. 179), Picasso began to produce similar works, which consisted of cutting and pasting pieces of different types of paper. Synthetic Cubism was not only a new conception of space: fragmented images now functioned as signs rather than descriptive representations of reality. In the best examples, such as Violin and Music Sheet, Picasso achieves serene compositions and beautiful chromatic combinations.