The Post-Impressionist Period: Background and Ambience

The Technical and Scientific Revolution

The period of Post-Impressionism began at a time of unbelievable changes in the world. Technology was generating true wonders. The development of science, which formerly had general titles – physics, chemistry, biology, medicine – took many different, narrower channels. At the same time this encouraged very different areas of science to combine their efforts, giving birth to discoveries that had been unthinkable just two to three decades earlier. They dramatically changed the perception of the world and humanity. For example, the work of Charles Darwin The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex was published as early as 1871. Each new discovery or expedition brought something new. Inventions in transport and communications took men into previously inaccessible corners of the Earth. Ambitious new projects were designed to ease the communication between different parts of the world. In 1882 in Greece the construction of the canal through the Isthmus of Corinth began; in 1891 Russia commenced the construction of the great Trans-Siberian railway which was finished by 1902; in America work started on the construction of the Panama Canal. Knowledge of new territories could not go unnoticed in the development of art.

At the same time there were great developments in telecommunications and transport. In 1876 Bell invented the telephone and, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century people began talking to each other in spite of the distance. In 1895, thanks to the invention of the telegraph Marconi discovered the telegraph, and in 1899 the first radio programme was broadcast. The speed of travelling across the Earth was increasing incredibly. In 1884 the first steam-car appeared on the streets of France; in 1886 Daimler and Benz were already producing cars in Germany, and the first car exhibition took place in Paris in 1898. In 1892 the first tramway was running in the streets of Paris, and in 1900 the Paris underground railway was opened. Man was taking to the air and exploring the depths of the earth. In 1890 Ader was the first to take off in an airplane; in 1897 he flew with a passenger, and in 1909 Blériot flew across the Channel. As early as 1887 Zédé had designed an electrically-fired submarine. It seemed like all the science-fiction projects of Jules Verne had become reality.

At the same period, scientific discoveries, barely noticed, but nevertheless significant for humanity, were taking place. In 1875 Flemming discovered chromosomes; in 1879 Pasteur found it was possible to vaccinate against diseases; in 1887 August Weismann published the Theory of Heredity. Lawrence discovered electrons; Röntgen did the same for X-rays and Pierre and Marie Curie discovered radioactivity. These discoveries in the field of science and engineering might seem distant from the Fine Arts, but nevertheless, they had a major influence on them. Technology gave birth to a new kind of art: in 1894 Edison recorded the first moving pictures, and in 1895 the Lumière brothers screened their first film.

European explorers became more and more adventurous, and brought back to Europe new and remarkable materials. In 1874 Stanley crossed Africa. In 1891 Dubois discovered the remains of a ‘pithecanthropus erectus’ on the island of Java. Previously during the 1860s, archaeologists E. Lartet and H. Christy found a drawing of a woolly mammoth engraved on a tusk in the Madeleine caves. It was hard to believe in the existence of Palaeolithic art, but further archaeological research provided evidence of its aesthetic value. In 1902 archaeologist Emile Cartailhac published a book in Paris called ‘Confession of a Sceptic’ which put an end to the long-lasting scorn of cave art. The amazing Altamira cave paintings, which had been subject to doubt for a long time, were finally proclaimed authentic. An intensive search for examples of prehistoric art began, which at the turn of the century turned into ‘cave fever’.

The end of nineteenth century also saw the birth of a new science: ethnography. In 1882 the ethnographical museum was opened in Paris and in 1893 an exhibition of Central America took place in Madrid. In 1898 during a punitive expedition to the British African colonies, the English rediscovered Benin and its strange art long after the Portuguese discovery in the fifteenth century. The art works in gold of the indigenous Peruvian and Mexican populations, which had flooded Europe in the sixteenth century after the discovery of America and had scarcely been noticed by the art world; it was nothing more than precious metal to be melted down. The expansion of European boundaries at the end of the nineteenth century opened incredible aesthetic horizons to painters. Classic antiquity ceased to be the only source of inspiration for figurative art. What O. Spengler later called the ‘decline of Europe’, which implied the end of pan-Europeanism in the widest sense of the word, had immediate effects on art.

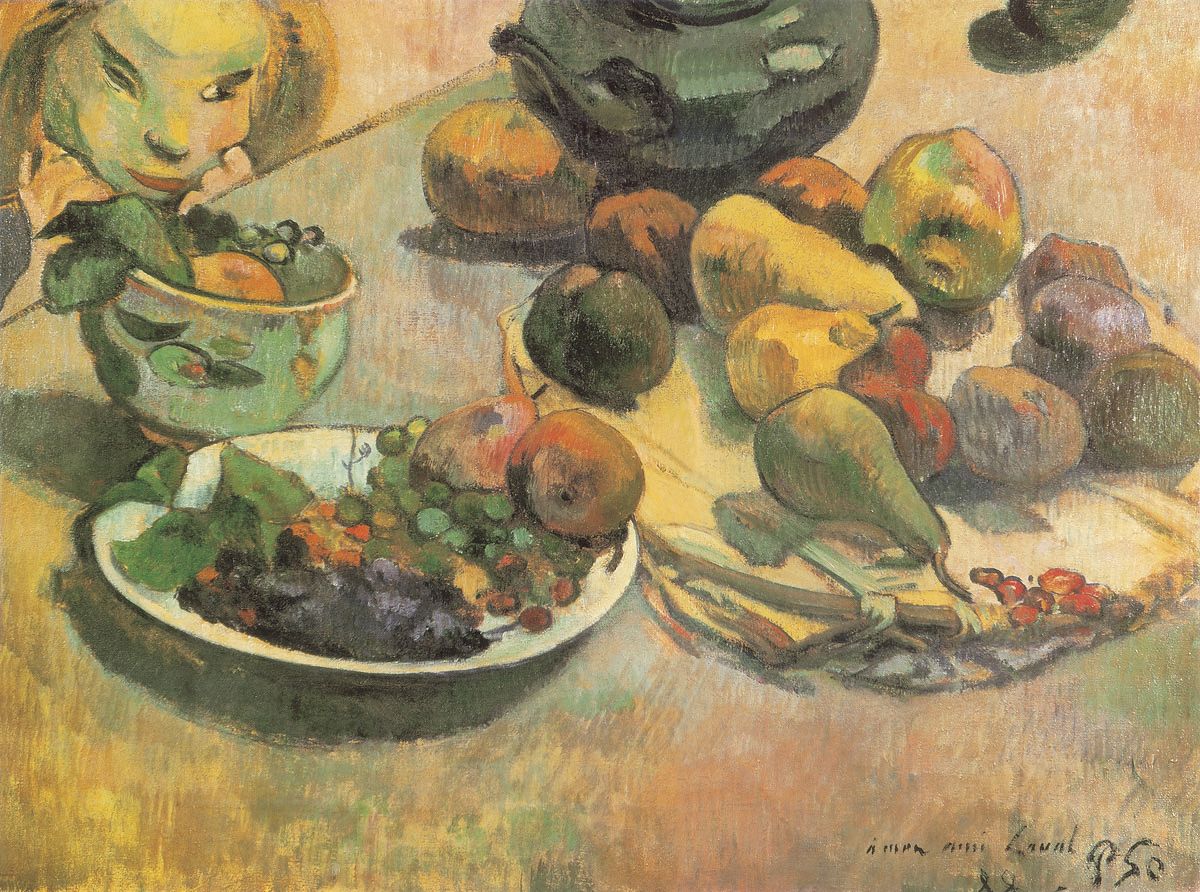

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Fruits, 1888. Oil on canvas, 43 x 58 cm. The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

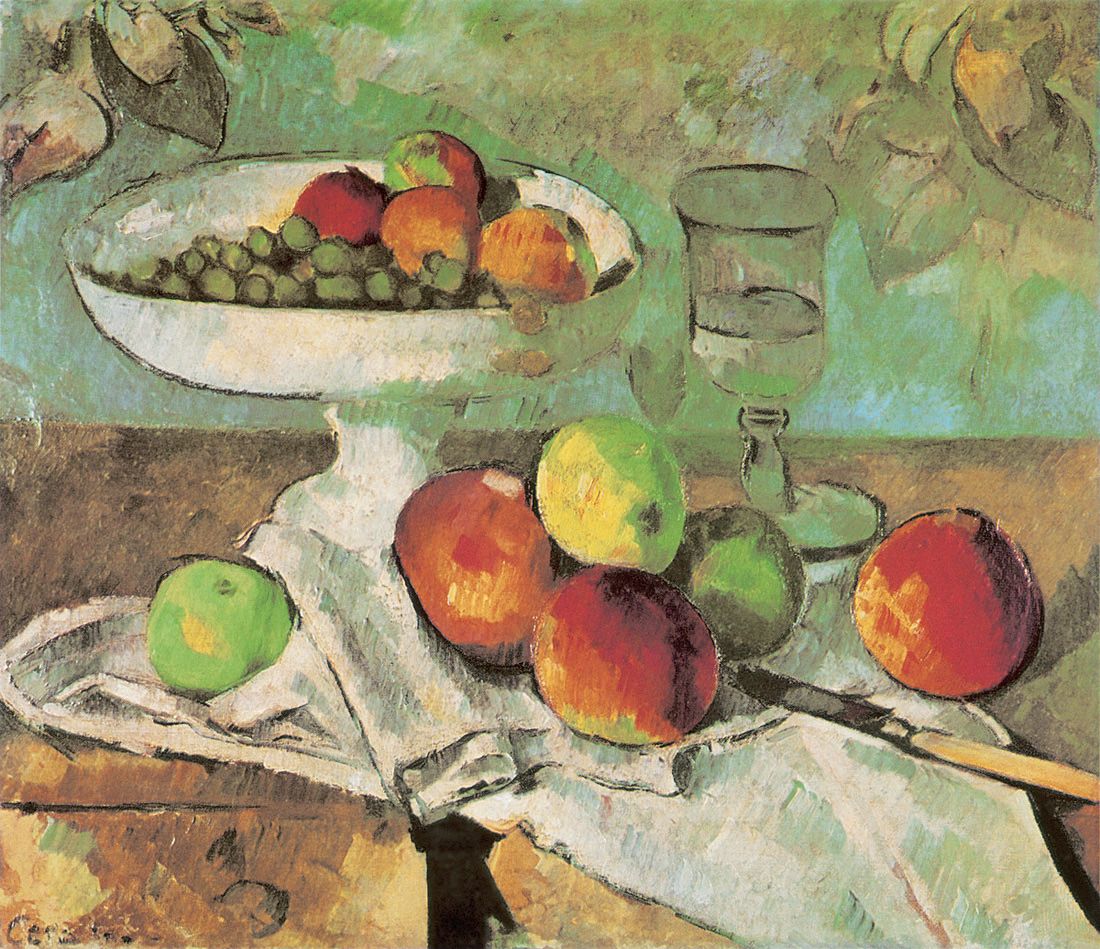

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Dish, Glass and Apples, 1879-1880. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. Private collection, Paris.

The year 1886 marked the beginning of fundamental changes in the appearance of Paris. A competition was organised for the construction of a monument to commemorate the centenary of the French Revolution (1789) which coincided with the World’s Fair. It was the project of the engineer Gustave Eiffel to build a tower which was accepted. The idea of building a 300 metre tall metal tower in the very centre of Paris alarmed the Parisians. On February 14, 1887, the newspaper Le Temps published an open letter signed by Francois Coppée, Alexandre Dumas, Guy de Maupassant, Sully Prudhomme, and Charles Garnier, architect of the Paris Opera building which was finished in 1875. They wrote: “We the writers, painters, sculptors, achitects, passionate lovers of the as yet intact beauty of Paris express our indignation and vigourously protest, in the name of French taste, in the name of threatened French art and history, against the erection of the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower right in the centre of our capital. Is the city of Paris to be associated any longer with oddities and with the mercantile imagination of a machine builder, to irreparably disfigure and dishonour it? (…) Imagine for a moment this vertiginously ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, overpowering with its bulk Notre-Dame, the Sainte-Chapelle, the Saint-Jacques Tower, the Louvre, and the dome of Les Invalides, shaming all our monuments, dwarfing all our architecture, which will disappear in this nightmare (…) And, for twenty years, we shall see, spreading out like a blot of ink, the hateful shadow of this abominable column of bolted metal.” [5]

Nevertheless, the World’s Fair of 1889 surprised Paris with the fine beauty of Eiffel’s architecture. During the exhibition 12,000 people a day visited the tower, and later it was used for telegraphic transmissions. But more importantly it finally became one of the dominant architectural features for which it had opposed. The city was moving towards the twentieth century, and nothing could stop its development. Given the metal market pavilions of Baltard and the railway stations, the Paris of Haussmann had no trouble adopting the Eiffel Tower. Amongst the Post-Impressionist artists of the period, some immediately welcomed the new architectural aesthetic. For Paul Gauguin the World’s Fair was the discovery of the exotic world of the East, with its Hindu temples and its Javanese dances. But the functional purity of the pavilion construction also impressed him. Gauguin wrote a text entitled Notes sur l’art à l’Exposition universelle, (Notes on Art at the World’s Fair) which was published in Le Moderniste illustré on July 4, 1889. “A new decorative art has been invented by engineer-architects, such as ornamental bolts, iron corners extending beyond the main line, a kind of gothic iron lacework,” he wrote. “We find this to some extent in the Eiffel Tower.” Gauguin liked the heavy and simple decoration of the tower, and its purely industrial material. He was categorically opposed to eclecticism and a mixture of styles. The new era produced a new aesthetic: “So why paint the iron the colour of butter, why gild it like the Opera? No, that’s not good taste. Iron, iron and more iron!” [6] The Post-Impressionist era was to dramatically change tastes and artistic passions. In 1912 Guillaume Apollinaire already designated the Eiffel tower as the new symbol of the city, becoming in his poems a shepherd guarding the bridges of Paris.

The year 1900 brought Paris new architectural landmarks: palaces appeared on the banks of the Seine, where pavilions for World’s Fair were traditionally built. Eugène Hénard drew up a plan for the right bank of which the principal feature was a wide avenue in the axis of the esplanade of Les Invalides and the Alexandre III Bridge. Along both sides of the avenue two pavilions were erected for the World’s Fair of 1900 – the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais – miracles of modern construction engineering. The principle of these constructions is that of a metallic structure surrounded by a façade of stone. The use of metal structures allowed decorating palaces with heavy stone and bronze sculptures in combination with painting and mosaic. These structures allowed to build a roof over huge spaces of the Grand Palais and to place spectacular halls for different kind of temporary exhibitions even industrial ones inside. Many famous sculptors and painters of the end of nineteenth century took part in the decoration of the palace, so that it became the monument to the new style, born in the era of Post-Impressionism.

At the same time, on the left bank of the Seine stood another palace. Well, it was not a palace as such, but the Gare d’Orsay and a hotel, built with the drawings of architect Victor Laloux. Trains were supposed to deliver visitors of the World’s Fair of 1900 directly in the centre of Paris. Contemporaries compared the station to the Petit Palais. “The station is superb, and looks like a Palais des Beaux-Arts. Just like the Palais des Beaux-Arts resembles a train station, I proposed to Laloux that he make the switch if there is still time,” wrote one of the artists after the opening of the World’s Fair. These new palaces completed Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paris.

Pierre Bonnard, Basket and Plate of Fruit on a Chequered Tablecloth, 1939. Oil on canvas, 58.4 x 58.4 cm. Gift of Mary and Leight Block, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

Théo Van Rysselberghe, The Reading by Emile Verhaeren, 1903. Oil on canvas, 176 x 234 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Ghent.

Symbolism and Literature

A significant change in the representation of world and man led to new tendencies in literature. Literature is always the fastest to react to changes in the surrounding world. Literature has always had the prerogative to form society’s outlook. Since the Renaissance painting has been closely tied to literature. It constituted the background on which the new styles of figurative art grew.

At the end of the century the interest for literature grew tremendously. Its circle widened and writers of many countries entered it. In 1886 France discovered the latest developments in Russian literature – Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky and Anna Karenina by Leon Tolstoy. Scandinavian countries opened a new world for the French with works of Ibsen, Hauptmann, Strindberg. The fascinating adventure novels Treasure Island and The Master of Ballantrae by the Scottish writer Stevenson were published in the eighties in Paris; then readers were introduced to Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde a novel that allowed them to look into the incredible abilities of man and the mysteries of his subconscious. Nietzsche and Schopenhauer’s works were published, Bergson’s philosophy astonished his contemporaries. At the turn of the century, the works of Freud and Jung were published. Literature covered a wide, unusual area; geographically the novels by Loti, Kipling, and Conrad took readers to distant unexplored countries which didn’t seem so distant any more. At the end of the century in France, The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man and, finally, The War of the Worlds by Englishman H.G. Wells were published. Wells thought that human imagination was not capable of creating something that could not happen in real life. His own works summarised the century, forecasting unbelievable cataclysms.

French literature had reached the peak of realism. “The naturalist school”, which had been in tune with Impressionists painting had not let go of this hold at the end of the century. Flaubert’s fame was still growing after his death in 1880; Maupassant, Goncourt, Daudet and, of course, Emile Zola, were still published. Zola remained one of the most significant figures in France’s social life. He used to gather writers at his house in Médan and published a compilation of their work. His chivalric defence of Dreyfus brought upon him the hatred of the right-minded community. However, realistic literature had passed its peak and was slowly becoming classical. The resentment of society now turned itself towards the new generation in literature. In 1870s, simultaneously with “naturalists”, names like Rimbaud, Verlaine, Leconte de Lisle, Huysmans, were quoted more and more often. In 1876 L’Après-Midi d’un faune by Stéphane Mallarmé was published, which lead to the creation of one of the most remarkable works of Debussy – Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. Music, just like literature, was starting something new in art, something that society was afraid of, it had barely finished digesting naturalism. In 1884 Huysmans’ novel A Rebours was published. The author had broken up with his friends in Médan and was now praising Mallarmé and the pro-Symbolism painters – Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon.

On September 18, 1886, the same year that saw the last exhibition of Impressionists, poet Jean Moréas published in Le Figaro the Symbolist Manifesto which gave the movement its name. Moréas established the new literary concept which was being developed at the time. Already in 1855, as Symbolism did not yet exist in literature, Charles Baudelaire published Correspondances, in the selection the Fleurs du mal. It sounded like the programme of a new literary school. “Baudelaire was its precursor”, wrote Moréas. Stéphane Mallarmé provided mystery and the unutterable; Paul Verlaine crashed for it the dreadful chains of prosody”. [7]

The head of this new school, Stéphane Mallarmé gathered its followers from 1884 on, inviting to his ‘Tuesdays’ painters, musicians, artists reviewers and theatre people. The Théâtre de l’Œuvre (‘Creation’) and the Théâtre-Libre (‘Free Theatre’) of the director André Antoine acquainted Paris with the works of Ibsen, staged plays of symbolist authors and of those close to them. There had been a new wave of interest for the German composer and philosopher Wagner after his death in 1883 and his music sounded in tune with Symbolism. Paris begun to take interest in Wagner for the first time in the beginning of 1860s, when, amongst others, Charles Baudelaire stepped up to support him. The attention towards Wagner was sparked again when the Eden-Theatre tried to stage Lohengrin in 1887. His music struck listeners with its exaltation and sudden changes from joyful to gloomy tones. Wagner’s strength lay in his mythological works which totally complied with the symbolists’ doctrine. In the middle of 1880s, in cooperation with Mallarmé, the Revue Wagnérienne started being published in Paris. It gathered poets, painters and musicians belonging to the symbolists’ circle. In 1891, Félix Vallotton, a painter from The Nabis group, painted Wagner’s portrait in woodcut style. And in 1889, two years before that portrait, the brothers Nathanson published the first issue of the magazine La Revue blanche; its publishers were hoping to lure symbolists writers and a number of painters close to the movement.

More than the mass of the lay audience, the protagonists of the old classical art schools reacted negatively to Symbolism. The originality of its creators was interpreted as affectation, caprice, a will to set themselves outside society. Symbolism was especially frightening because it was not just a style in literature or art but a philosophy, a different perception of reality, a new ideology. It was formed as a result of that great revolution in science that shook and scared contemporaries. It seemed there was a rational explanation for everything in life and there was nothing mysterious left in nature. Symbolism stood against science and technology, trying to make spirituality a priority over materialism in art. Instead of scientific logic, its followers turned to intuition, subconscious and imagination – forces that inspired the fight against the sovereignty of matter and the laws of physics.

As for literature, Symbolism had only one big enemy – realism. The prose of everyday life, praised by the naturalistic school, was opposed in Symbolism by mysticism, the mystery of the after world, and the search for a hidden meaning in every event or image. Symbolism invited everyone to listen to the great strange world surrounding us, to find the meaning of life, which is possible only for the true creator. Overflowing imagination that remained out of reach for an average painter, took the place of life observation. Searching for the secret of this imagination, surrealists turned to Symbolism later in the twentieth century. In the Surrealism Manifest André Breton said that the symbolist poet “Saint-Pol-Roux, when he went to bed in his manor house in Camaret-sur-mer used to post a notice on his door which read: THE POET IS WORKING.” However, symbolists didn’t mean that the painter literally dreamt images. The reverie, praised by them in literature and art, was an incarnation or even a symbol of their extraordinary imagination that could rise above the reality.

It seemed that with the death of Hugo in 1883 Romanticism, under which sign the painters in the middle of the century were creating, started to go down completely. Saint-Pol-Roux, whilst analysing Symbolism, said: “Romanticism praised just twinkles, shells and bugs that can be found in the sand. Naturalism counted every single grain of sand. The next generation of writers, having had enough time to play with the sand, would blow it off to find the symbol hidden under it…”.[8] Although Post-Impressionism contemporaries thought of Romanticism as an antiquity, in reality it was just hidden for a while, stepping back under the pressure of Realism in all its forms. Now Symbolism became its closest successor. Symbolism researchers sometimes even call it the “Post-Romanticism”. Symbolism, just like the Romanticism of the first half of the nineteenth century, was represented in brighter colours in literature, but did influence all types of art.

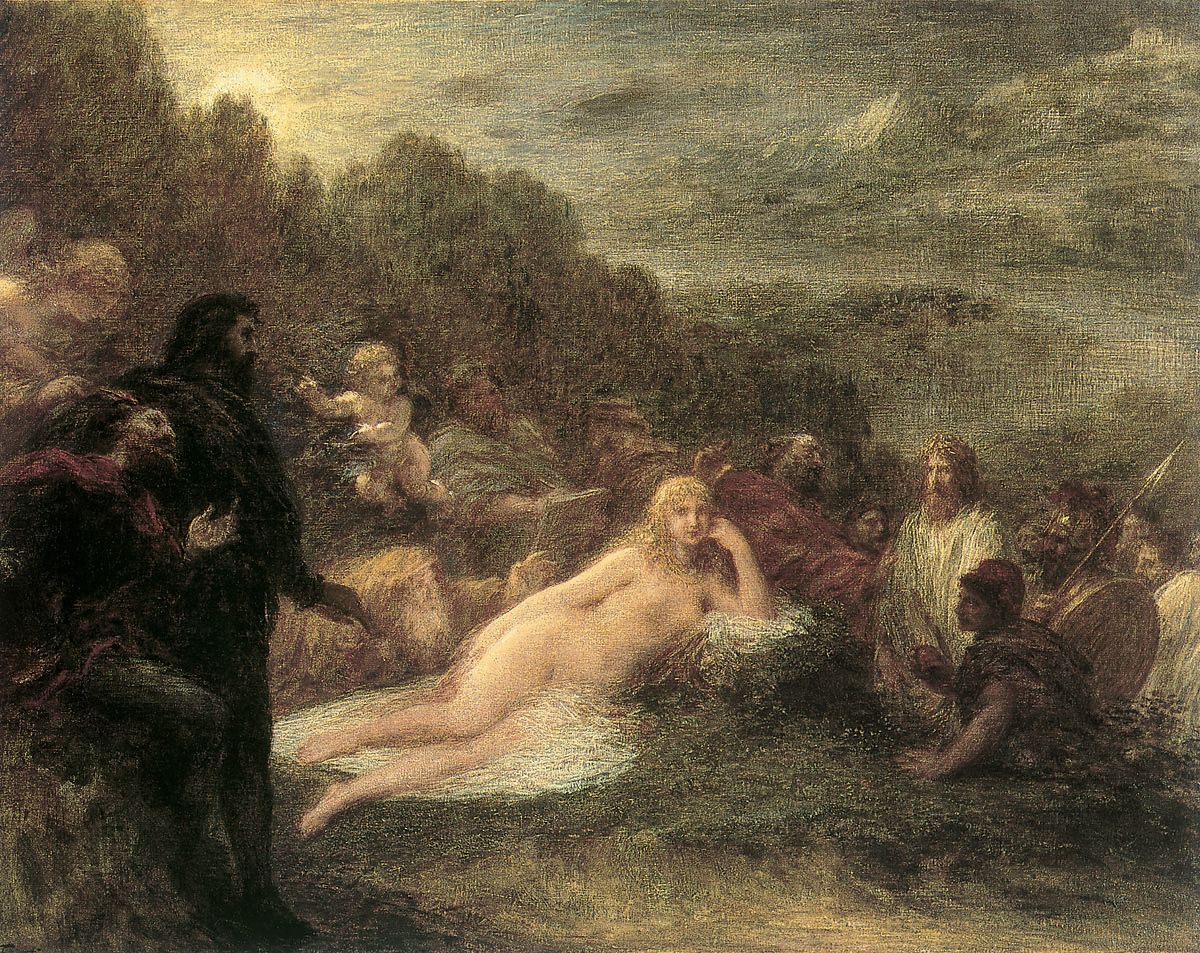

Henri Fantin-Latour, Hélène, 1892. Oil on canvas, 78 x 105 cm. Petit Palais – Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Paris.

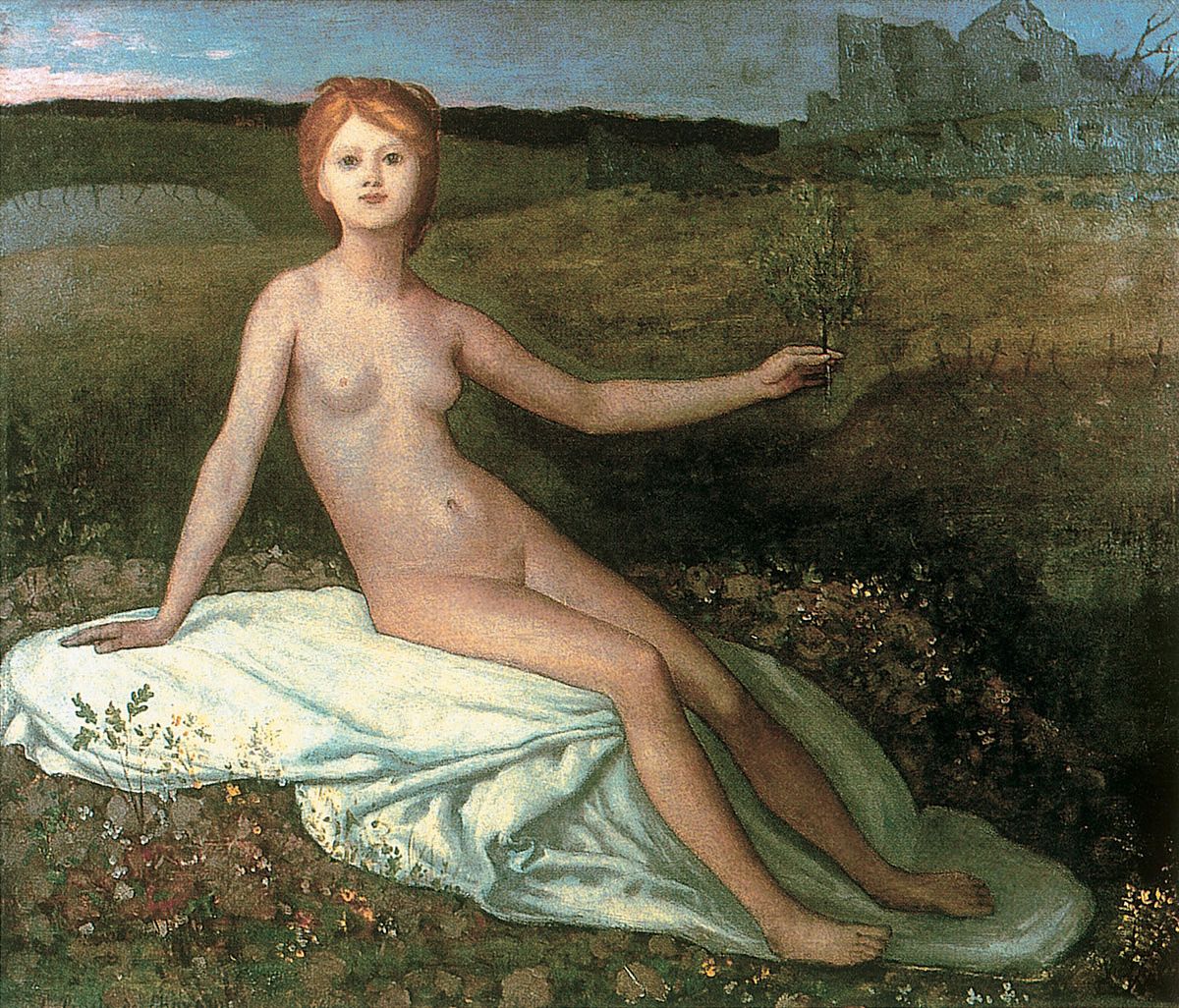

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Young Girls by the Seaside, 1879. Oil on canvas, 205 x 154 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Symbolism in literature, which Jean Moréas presented and explained in 1886 in his manifesto, had, by this time, already fully developed. Moréas stated that for every new style there is always degradation and a death of the previous school. “Romanticism, which loudly raised the alarm of the riot and lived through the days of battles and glorious victories, has now lost its might and charm (…), and exposed itself to Naturalism…” he wrote. [9] Naturally, it was Naturalism that was under the strict critic and condemnation of symbolists. The evocation of naturalism in literature for them was still Emile Zola. With all the admiration that Mallarmé had for Zola’s talent he still thought that his works were at the lowest level of professionalism in literature. Remy de Gourmont, in the heat of the battle, called Zola’s work “culinary art” that uses only readymade ‘slices of life’ disregarding ideas and symbols. [10] Answering the question of Naturalism, Stéphane Mallarmé found a term for its description from the treasury of symbolists’ literature. “Up until now literature childishly imagined,” he wrote, “that just by picking up some precious stones and then writing their names down in a most beautiful writing on a piece of paper it could make precious stones. That is not the case! (…) Things exist without any regard to us, and it is not our task to recreate them; all we are supposed to do is to find a link between them.” [11]

The priority of these links in the new world outlook was beautifully described by Charles Baudelaire in Correspondances:

“Nature is a temple where living pillars

Sometimes emit confused words;

There, man passes through forests of symbols

Which observe him with familiar gazes.”

Nature is trying to speak to man in its own language that he is not capable of understanding; this language is full of obscure symbols and it would be pointless to try and decipher them. The attractive power of Symbolism, in contrast to the clarity and simplicity of Naturalism, lays precisely in its enigma, in its deeply hidden mystery, a key to which does not really exist. The difference between Symbolism and Naturalism was best described by Emile Verhaeren: “Here, before the poet, is Paris at night time, myriads of twinkling dots in the infinite sea of darkness.” He (writer - N.B.) can describe this image directly, the way Zola would have done it: describe streets, squares, monuments, gas lamps, inky darkness, feverish movements under the gaze of the still stars, this way he will definitely reach the literary effect but there will be no sign of Symbolism there whatsoever. He can also instil the same image into readers’ imagination just by saying, for example: “it’s a gigantic cryptogram the key to which is lost”, and then, without any description and recitation, he will fit the whole of Paris into one phrase: “its light, its darkness, its magnificence.” [12]

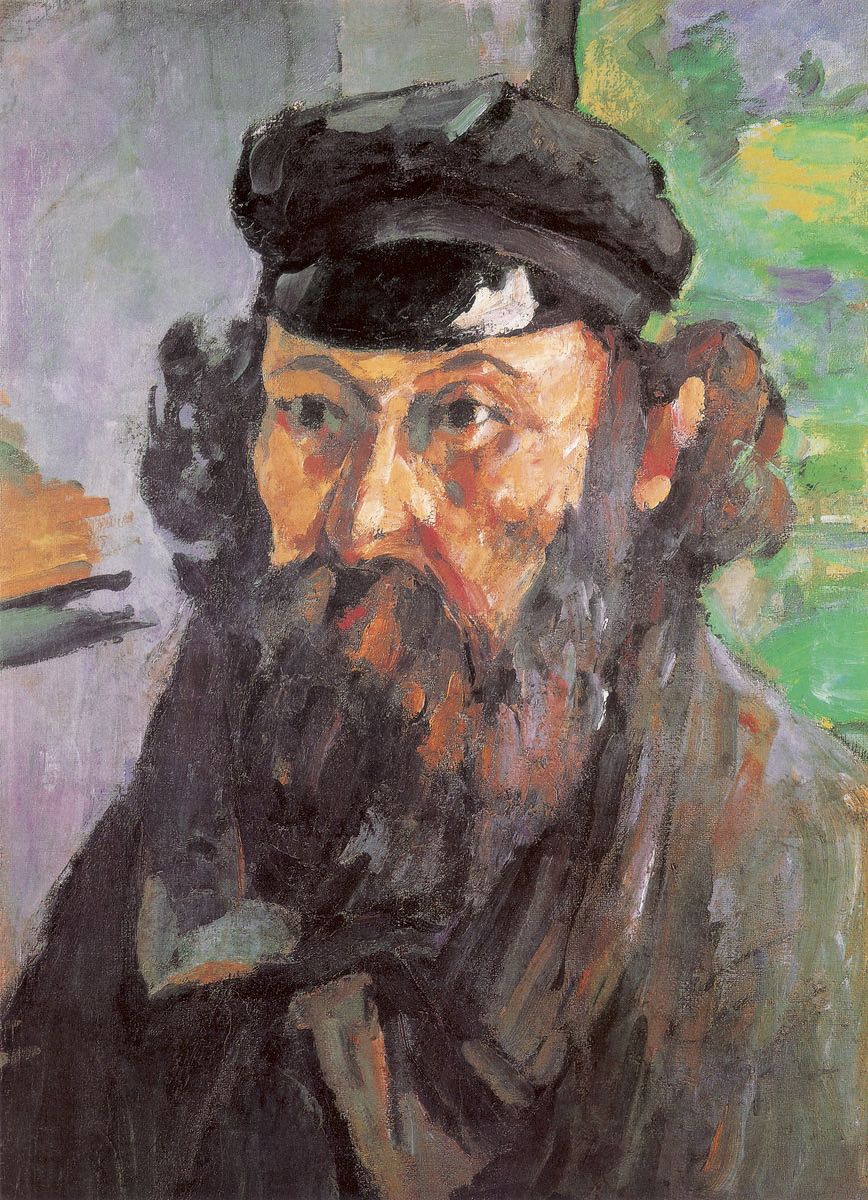

Only the chosen artist, the individualist painter, could create a symbolic image far from reality. According to Mallarmé, “it is a person secluding himself deliberately in order to create his own headstone…” [13] The Symbolists created something like the cult of the chosen individualist. Reciting the qualities of Symbolism, Remy de Gourmont quoted individualism, freedom of creation, refusal of academic formulas, longing for all things new, unusual and even strange. “Symbolism (…) is nothing but an aspect of individualism in art” [14] – he wrote in the Book of Masks, illustrating his thesis with the brilliant literary portraits of symbolist poets. Remy de Gourmont calls them “Narcissuses in love with their own image.” [15] His psychological analysis of each of those strange personalities leads involuntarily to a comparison with equally strange and unusual – for their contemporaries – individualist painters of the Post-Impressionism era: Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, the Douanier Rousseau. The sensitivity of their painting, which depended not on nature but on the individuality of the master, perfectly matches the credo of the symbolist poets. Defining a new form of creation, Remy de Gourmont wrote about Maeterlinck that he had “found a hollow unexpected cry, a, vaguely mystical groan”, which maximised the mystical signification of his works. [16] Mysticism, which is an essential feature of Symbolism, got closer to Individualism. “Mysticism”, says Remy de Gourmont, “can be viewed as the state of a soul which does not feel connected to the physical world, it cast everything accidental and unexpected aside and it gives itself exclusively into the direct adulation with infinity.” [17]

Above all, mysticism riddle without a key, went from literature to figurative art through the subject. Poets and painters were looking for symbolic plots in religion. “As the result of religion”, wrote poet Georges Vanor, “symbols finds its roots in the teaching of Zoroastrian priests, who imagined the world as an egg containing forces of good and evil…” [18] The author of the Manifesto, Jean Moréas, thinks that there always were plots in literature worthy of Symbolism. “Pindar’s Pythian Odes, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Dante’s Vita nuova, Goethe’s second part of Faust, Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony – don’t they all have a mark of the mystery?” – he writes in the manifesto. [19] Painting used them many times in the process of its existence, however, now it’s trying to find a symbol in them and through it to reveal an idea. German romantics were very good at finding plots for literature and painting. They drew them from nature; they studied the fairy tales and myths of different countries, seeking out the most concise symbols. Maeterlinck thought that there is a subconscious symbolism that appears apart from the creator’s will: “It is incidental to all masterpieces of the human soul,” he declared in one of his interviews, “the first examples of it are the works of Aeschylus, Shakespeare…” [20] Maeterlinck’s works, according to Remy de Gourmont, represent a construct and possibly an etalon of a symbolic plot. In the Book of Masks he recreates a typical Maeterlinck plot:

“Somewhere in a mist there is an island. On the island there is a castle. In the castle there is a big hall illuminated with a little lamp. In the hall there are some people who are waiting. Waiting for what? They don’t know. They are waiting for someone to come and knock on their door. They are waiting for the lamp to go out. They are waiting for horror. They are waiting for death… It’s too late. May be it will come only tomorrow! And people, gathered in the big hall illuminated with a small lamp, are smiling. They have hope. And then, finally, there is a knock. That’s it. This is the whole life. This is the only life.” [21]

Fine Arts and Symbolism

A work of art that’s connected to the ideas of Symbolism cannot be the subject of easy objective reading or contemplating. Alfred de Musset wrote that Romanticism is all that moves and thrills the soul; the same can be said about Symbolism. Except, that Symbolism also contains something odd, mysterious, something from the afterworld, terror and the sense of absolute loss…

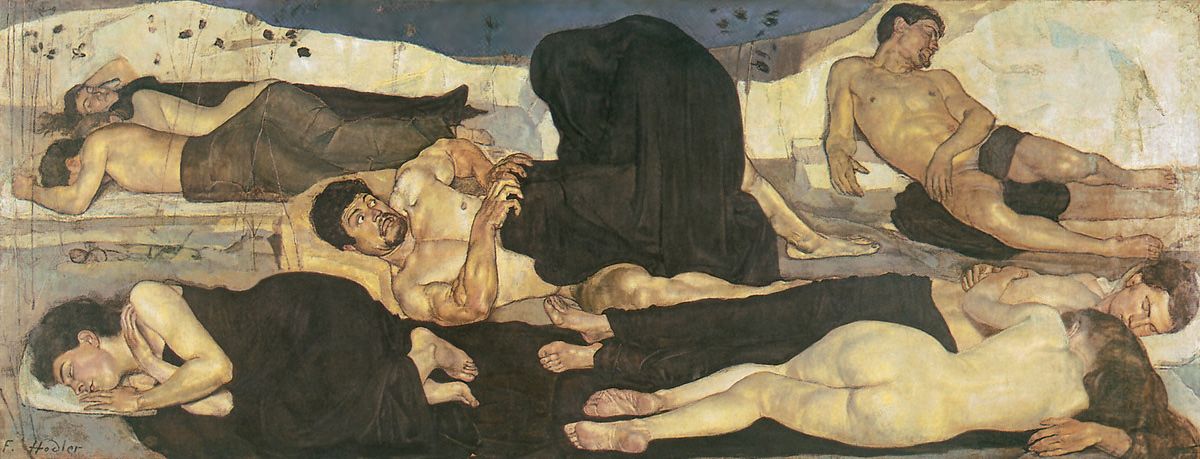

Remy de Gourmont, thinking about literature, said that Symbolism is antinaturalism. In this case, for painting, sculpture and graphic it’s antirealism and anti-impressionism. However, whether realism and impressionism were new trends with their very own ideology and system of expressive means, Symbolism in fine arts was more of a reflection of the literary-intellectual movement. Ideas of Symbolism dominated minds in Post-Impressionism era, and were present in works of painters who were very different in their creative styles. The title of Symbolists’ teachers in fine art of the last century can be given to the great visionaries, those, whose hallucinations became a generalised expression of human emotions: the Spaniard Goya, the British Blake, and the Swiss Füssli. The immediate predecessors of the symbolists were the German romantics – Friedrich, Runge, Nazareans and the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. At the end of the nineteenth century there were a few dozen painters in Europe who tied their work in with ideas, symbols, graphic system and the plots of symbolist literature. In Germany they were called “late romantics”: Arnold Böcklin, Hans von Marées, Hans Thoma, Franz Stuck. In Belgium, Fernand Khnopff stood out from the whole group of symbolist painters; in Norway – Edvard Munch; in Russia – Mikhail Vrubel; in Switzerland – Ferdinand Hodler. Amongst the symbolists there were those who created and expressed in the brightest way the new art style at the turn of the century. The art style that had different names in different countries: in France – ‘Art Nouveau’, in Germany – ‘Jugenstil’, in Russia – ‘Modern’. The Decorative styles of English Aubrey Beardsley, Austrian Gustav Klimt, Czech Alfons Mucha, and Swiss Eugène Grasset were the brightest expression of this new style in graphics, posters and stained glass. In some cases Symbolism just touched in passing some major masters without becoming the main line of their work, for example Auguste Rodin.

In France, the motherland of Impressionism, Symbolism echoed in plastic arts, the same as everywhere else, mostly in the form of a literary plot. The perception of a picture based on a story or a novel was still very strong despite the Impressionists’ attempt to free painting from literature. The school was still producing ideally prepared painters-craftsmen who created masterpieces in traditional classical style and painting technique. In the Salon every year they exhibited practically the same usually fashionable pictures with the plot and characters taken out of antique mythology or the Holy Scriptures. Only now they had a shade of mysticism, mystery, mortal fate and melancholy. They still received, just as before, the Prix de Rome. The professors of Cabanel, Baudry, Bouguereau, Bonnat could still be proud of their students who were made popular by a touch of Symbolism. Albert Besnard received the most prestigious requests for painting, at the Paris Town hall, at Sorbonne, at the Petit Palais that was still undergoing construction for the upcoming World’s Fair of 1900. Georges Clairin was painting portraits of the high society. Henri Le Sidaner and Henri Fantin-Latour were drawing lithographs, spellbinding the viewer with their tender sadness, reminding them of Wagner’s images and mysterious apparitions. Between 1892 and 1897 the New Salon, which welcomed young artists following the ideas of Symbolism, opened its doors six times. It was supported by Joséphin Péladan, also known as Sâr Péladan, a member of the Cabalistic Order of The Rose and The Cross. This order was created on the basis of the secret Rosicrucian societies of the eighteenth century, from which it retained an interest in symbols of the Middle Ages, alchemy and esoterism. However, Sâr Péladan had never exhibited those painters for whom Symbolism was nothing deeper than just a literary plot and who came closer to expressing its ideas with the help of their graphic tools.

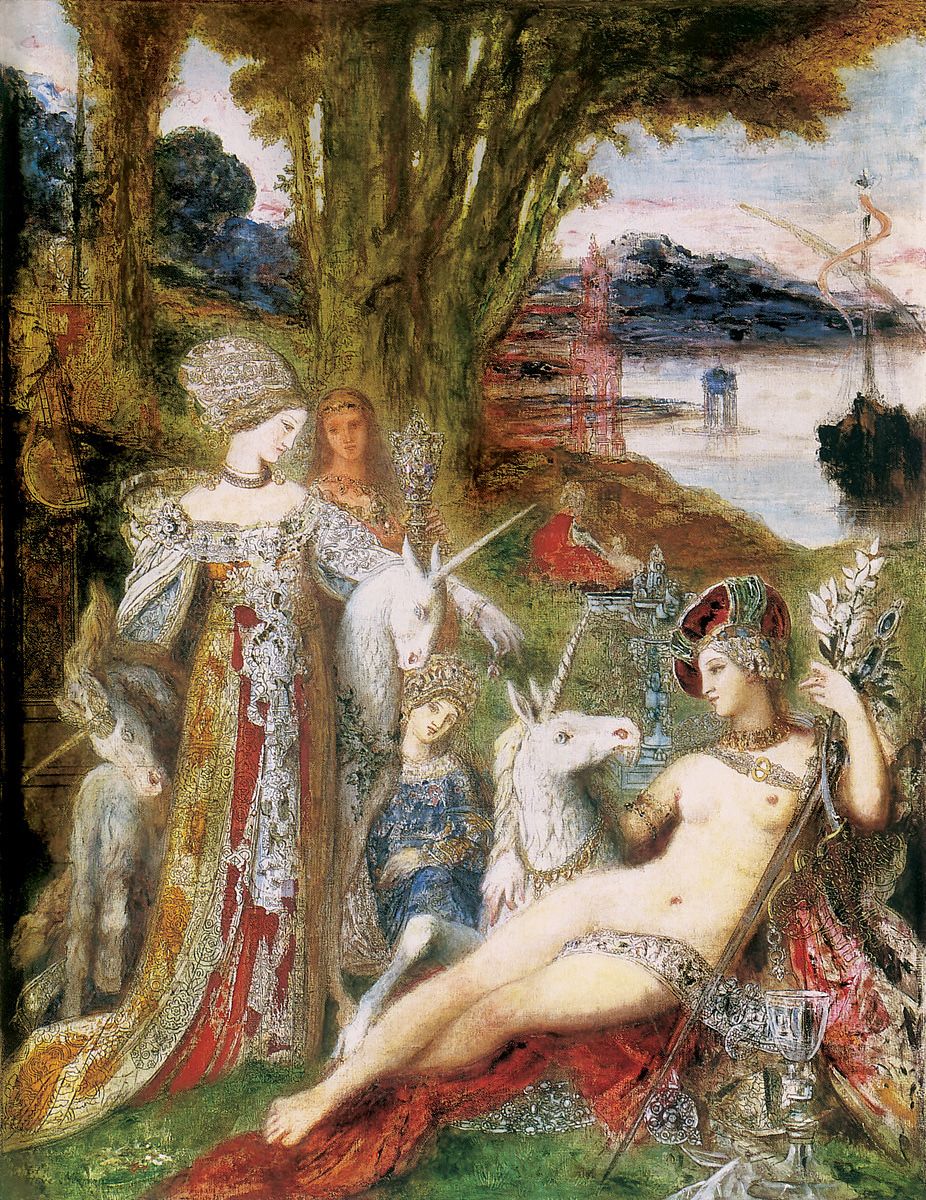

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, the author of the monumental murals, could create a feeling of mystery and dreaminess with the help of generalisation of forms, bright colour scheme and strangely immobile female figures. A woman-myth, beautiful to perfection and unreal, one of the most characteristic images in Symbolism, appears also in the works of Gustave Moreau, for whom the power of painting was in the colour. His fairies, unicorns and antique characters were born in the whirlpool of colours, in bright colour schemes, that is precisely what makes them so intriguing and mysterious. Cabanel’s pupil Eugène Carrière, on the contrary, takes you away into the land of dim apparitions with the help of his monochrome style painting. Colours were non existent for him; also he applied slightly varying shades of colours, which submerged his characters into a surreal and misty world of dreams. Finally, Odilon Redon, remarkable artist of the end of the nineteenth century, not only worked within the spirit of the times, but was a true visionary. Even though he learnt from Gérôme, one of the most official and worldly painters, he was under a greater influence from the lessons of the botanist Clavaud and the painter Bresdin, who recreated Redon’s hallucinatory world in his engravings. One can only compare strange and sometimes monstrous images of Redon’s drawings of fauna and flora, to Hieronymus Bosch’s visions. In his paintings, colours sometimes melt into soft and misty grades ranging from one side of the spectrum to the other and sometimes still they startle you with the strange contrast of bunches of simple wild flowers. Redon’s symbolism was spontaneous and instantaneous, and his work mostly influenced his youngest contemporaries. Paul Gauguin evoked Redon in his letters from the South Pacific islands, and Maurice Denis painted him as a teacher in his Nabis group of friends in his 1900 Homage to Cézanne painting.

The symbolist poet and critic Albert Aurier, in his article “Paul Gauguin: Symbolism in painting” published in March 1891 in the Mercure de France, tried to put together the basic laws of symbolist art. Five elements stood out, all typical in literature as well as in painting. Three of them (idealism, the symbolic nature and subjectivity) formed the basis of the symbolist perception of the world.

The last two (synthesism on a general meaning; and in a decorative aspect) involved a direct means of expression. Aurier said a painter-symbolist must simplify the tracing of symbols. Symbolists proclaimed the subjectivity of art. Consequently every contemporary painter of Aurier understood those laws differently; however, every one of them one way or another incarnated them in their works. Symbolism became the background for the mixed and contradictory art of the Post-Impressionism Era.

Gustave Moreau, Dead Poet Carried by a Centaur, c. 1890. Oil on canvas, 33.5 x 24.5 cm. Musée Gustave Moreau, Paris.