Prologue

Although Camille Claudel’s name has always been connected with Auguste Rodin, there is no denying that she was an artist in her own right. Camille’s strength came from within; she endured the anger and disapproval of family members, Rodin’s refusal to marry her, and the rejection of her work by several French ministries, who, in their capriciousness then denied her commissions. She chose a difficult medium to work in, yet from this medium came a sensuality, a love of the human body, and emotions so deep that we are caught up in what she must have felt during the creative process. Many of her works have disappeared or were destroyed, but enough remain that we can see the essence of the person that was Camille Claudel.

Chapter One

Camille Claudel was born on 8 December 1864 in Fère-en-Tardenois, a village in France’s Champagne district. Citizens of the area were hard-working conservatives concerned with making a decent living under society’s scrutiny and approval. Many earned their living as farmers, shopkeepers or artisans. Her parents, Louis-Prosper and Louise-Athanaïse Cerveaux, had married in 1860. Louis-Prosper, educated by the Jesuits in Strasbourg, was employed as a registrar of mortgages in several towns, including Bar-le-Duc, where in 1870 Camille first attended a school conducted by the Sisters of Christian Doctrine. Although essentially middle class, the Claudels considered themselves a step above others in the community. Louise-Athanaïse’s father had been a physician and it was she who provided a home in Villeneuve-sur-Fère, about eight kilometres from Fère-en-Tardenois, and where the family eventually settled about four years later. Although they moved several times over the years, the family always came back to Villeneuve-sur-Fère for the summer.

Camille’s sister Louise was born in 1866 and her brother Paul two years later. Paul was to become a diplomat, poet, and the sibling that Camille turned to during times of stress. The family’s relationships often became strained and volatile. Camille’s mother, a plodding woman with strong moral sensitivities, would later refuse to see, speak to or support her daughter. Camille’s support came primarily from men; within her family it came from her father and Paul.

Within the village of craftsmen and construction workers, old hatreds, gossip and backbiting smouldered constantly. Most of the small-minded atmosphere was lost on Camille once she discovered the red clay used in constructing roof tiles for buildings in the area. When she found that by digging her fingers into the clay and working her hands around it she could form intricate shapes that held their form after they were baked in the kiln on the family property, nothing else held her attention. From then on, she forced others – usually friends and siblings – to share her interest, employing them as clay gatherers, models or plaster-preparers. As they tired of her projects, they usually disappeared when they saw Camille coming.

A picture of Camille Claudel at the age of 14 shows a pensive young adolescent, her dark eyes and straight mouth in an expression bordering on sadness. The Claudels had moved to Nogent-sur-Seine, about one hundred kilometres from Paris, two years earlier. By that time her drawing talent had already been recognised by her art teachers, but she also studied independently and used miniatures and old engravings as inspiration when creating sculptures of Greek and historical personages. Only three works survive from that period: a sculpture of David and Goliath, Napoleon I and Bismarck. Her work caught the attention of the young sculptor Alfred Boucher, a native of Nogent then living in Paris. Boucher would occasionally visit his home town and when he went to Camille’s studio and saw her work he returned often to give her lessons and provide the mentoring she needed.

In Nogent, Camille’s artistic development also flourished under the guidance of Monsieur Colin, who had been hired by her parents to oversee their children’s education. By giving the children a firm foundation in mathematics, spelling and Latin, Colin provided the Claudel girls, as well as their brother, with a better education than they might have had had they attended the public schools in the area. These two instructors, Boucher and Colin, undoubtedly formed the basis for Camille’s artistic and intellectual development. Yet Nogent itself was limited in terms of offering opportunities for her as a sculptor. A woman in the mid-19th-century provincial France received art instruction patterned after the École Gratuite de Dessin pour les Jeunes Filles, a school of design in Paris. This enabled her to work as a teacher or in an area of manufacturing. Attending a serious art school employing nude models was unheard of in the provinces.

In 1881 Louis-Prosper was transferred to Wassy-sur-Blaise, but, concerned that his children should receive the best possible schooling, he made arrangements for Louise and the children to secure an apartment in Paris. Paul Claudel years later told a different story: that Camille, anxious to further her artistic studies, begged to live in Paris where women were admitted to institutions that offered access to nude models. In the 19th century, the ability to draw and sculpt the nude model was the standard by which all artistic ability was judged. Louise Claudel may have objected to this arrangement, since she preferred the stable, family-oriented setting of the countryside, where women learned household skills, married and produced children. But for Camille to live alone in the heart of Paris in order to attend school was definitely out of the question.

So in 1881, at the age of seventeen, Camille Claudel got her first taste of Parisian life. It was almost as if the city had revitalised itself in anticipation of her arrival. Following the bitter and tragic Franco-Prussian War of 1870, in which France was defeated and Paris suffered the worst siege in its history, the third French Republic was established. This resulted in a period of patriotic fervour; statues of women representing the Republic or Joan of Arc sprouted up in towns and villages across the country. Artists established studios on virtually every street on the Right Bank in the vicinity of Clichy and Rochechouart. In the early morning or evening they could be seen rushing along the pavement, paint boxes and portfolios clutched in their arms.

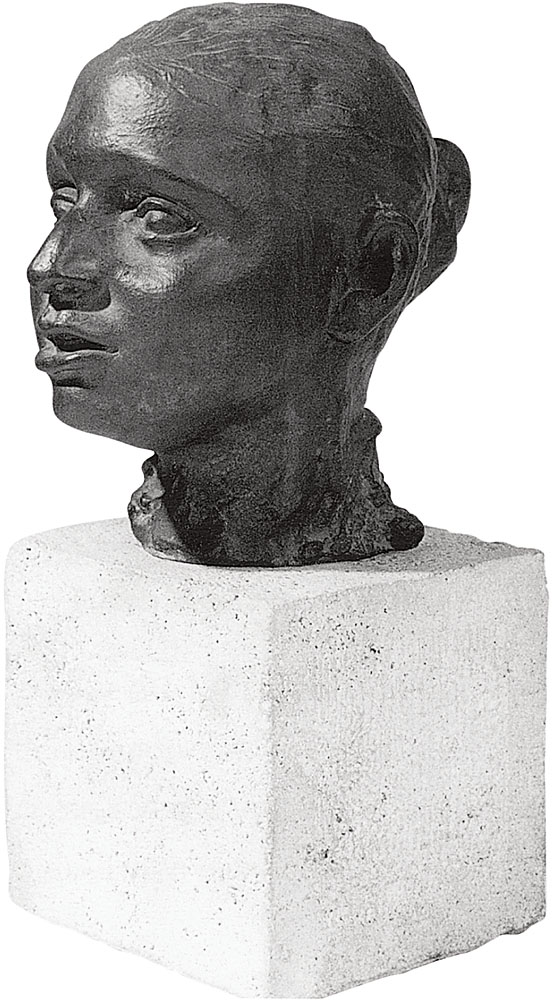

Young Woman with Her Eyes Closed, c. 1885

Bronze, cast posthumously, 37 x 35 x 20 cm. Private collection

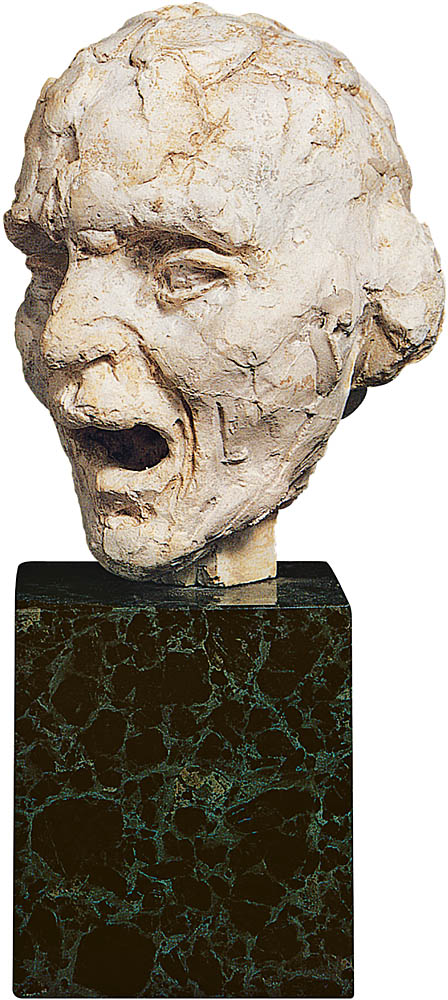

Study for A Burgher of Calais, 1885

Bronze on a cube of red, veined marble, 15 x 10 x 13 cm (without socle). Private collection

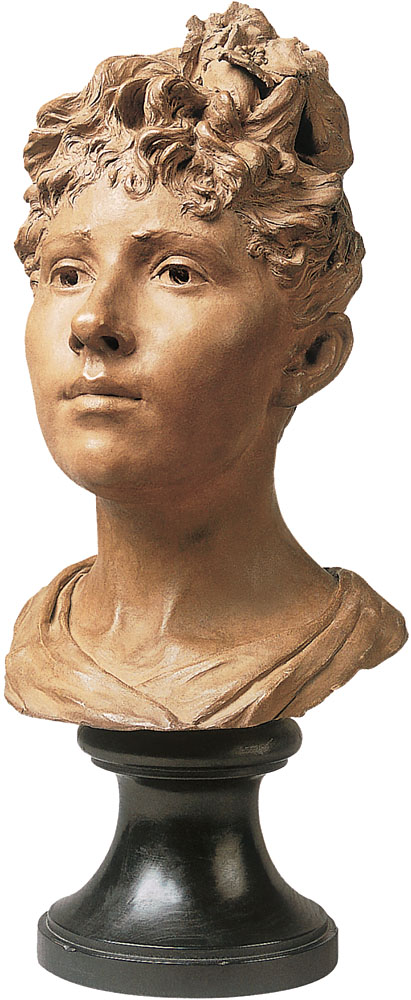

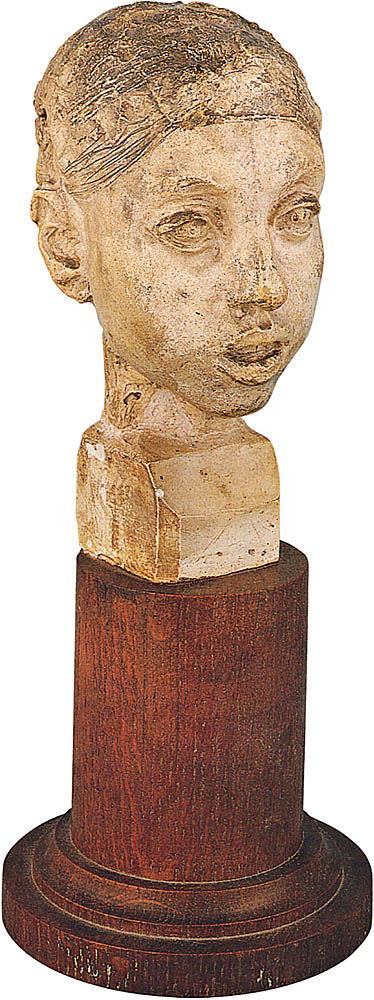

Louise Claudel or Madame de Massary, c. 1885

Terracotta, 49 x 22 x 25 cm. Palais des Beaux Arts de Lille, Lille

Man with His Arms Crossed, 1885

Bronze, cast posthumously (2003), 10 x 9.5 x 8 cm. Private collection

Chapter Two

Once the family was established in an apartment on the Boulevard du Montparnasse in Paris, Camille Claudel enrolled in the Académie Colarossi in 1881. The school had a democratic approach to learning: women studied side-by-side with men and, unlike other art academies that often charged women double the tuition of their male counterparts, the Colarossi charged the same tuition for both sexes. In general, it was also less expensive than many other institutions in the city. Established artists and sculptors regularly visited the students’ ateliers to give instruction, and the Colarossi provided a stronger focus on sculpture than other art schools in the city.

Camille at first used a section of the Claudel apartment as her atelier, then later found a studio at 117 Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. The family moved to an apartment at 111 Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs near the studio and not far from the Colarossi; two English girls shared the studio. Albert Boucher was a frequent visitor, giving advice and bringing with him his mentor, Paul Dubois, director of the École des Beaux-Arts. Apparently impressed with her talent and energetic approach to her work, Dubois casually asked her if she had taken any lessons from Rodin. Not only had she not studied under Rodin, she had never heard of him.

In 1882 Boucher left for Florence after he was awarded the Grand Prix du Salon the previous year. He asked Rodin to take over instructing his protégées, including the talented seventeen year-old Camille Claudel. Rodin, at 42, was living with his mistress, Rose Beuret. The couple had a son, Auguste, just two years younger than Camille herself. Rodin’s artistic career had consisted primarily of commissions to produce decorative figures for major buildings or façades, but in the late 1870s, he was anxious to satisfy his creative needs and produced his first major work, The Age of Bronze, a young man, nude, his arms raised in a gesture of self-discovery. Initially, the work was criticised by the artistic community, who insisted that the figure had been cast in plaster using a living person. In time, Rodin’s integrity was validated and the French government purchased the piece along with a statue of John the Baptist.

In late 1882 or early 1883, when the 42-year-old Rodin first visited the studio in Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, he most likely would have found several young women hard at work and projects in various stages of completion around the room. Photographs of Camille’s studio show Persian rugs on the wall, a piano off to one side and several decorative objects, including a plaster parrot, filling the area. At the time, Camille had two or three works displayed in the room. One was a bust of her brother titled Paul Claudel at Thirteen; another, Old Helen or Bust of an Old Woman, and there may have been a work in progress, Bust of Madame B., although it seems that the work has disappeared.

Head of a Slave, c. 1885

Grey clay on a socle of green marble, 13 x 8.5 x 11.5 cm; socle: height: 9 cm; diameter: 10.5 cm; height including socle: 22 cm. Private collection

Paul Claudel at Thirteen shows a princely young boy, reminiscent of a Roman nobleman on the threshold of maturity. It clearly reflects Camille’s devotion to her brother, and was somewhat prophetic; Paul later became a well-known poet and writer and spent several decades in the foreign service. Old Helen or Bust of an Old Woman, in contrast, is a bust of one of the Claudel servants, an old woman, her head cocked to one side, with the characteristics of age, wrinkled brow, a forced grin and a no-nonsense expression in her eyes. It is possible that Camille completed the Bust of Madame B. under Rodin’s guidance.

Claudel had chosen a difficult, almost cruel medium for self-expression. Being a sculptor in the nineteenth century meant breathing in dust and dirt, engaging in the strenuous tasks of hauling water, constructing armatures, digging into clay and then cleaning up at the end of the day. The financial rewards seldom compensated for the work involved. For a woman at that time there was an added dilemma: she was hampered by the confining clothes of the period. If she wanted to wear trousers, she needed permission from the prefect of police.

The cost of materials presented another problem. While a sculptor might be able to afford clay or plaster, the materials were fragile. Works were preserved and duplicated when they were cast in bronze at the foundry, but the artist had to include the cost of bronze and the foundry’s services, and that was where the expenses were heaviest. Add to that the cost of a model and the rent on the atelier, and simple day-to-day living expenses. Often it was only the artist’s passion that kept him from pursuing another field. Most took on decorative or teaching jobs to survive.

In the 19th century, the founder used the lost-wax method of casting to make the reproduction as faithful as possible to the original. He made a plaster negative cast from the original, coated the new cast with layers of wax, and poured another layer of plaster over the wax. These two plaster moulds were held in place with bronze pins. The forms were then heated to melt the wax, which escaped through thin cylinders (sprues). He poured the liquid bronze into the void replacing the “lost wax.” The sprues were cut off, section joints removed and the bronze polished. Bronze casting made it possible for several reproductions to be made so that the artist could realise a profit from his original work. Stone carving, usually from marble, was expensive and, of course, one bad chip and the piece was ruined.

Young Woman with a Sheaf, 1887

Bronze, cast posthumously (1983), 35 x 20 x 20 cm. Private collection

Young Girl with a Bun, c. 1888

Bronze, cast posthumously (1985), 17 x 9.5 x 14 cm. Private collection

Chapter Three

Rodin, seeing Camille’s talent and dedication, elevated her from student to apprentice in 1884. He had several artists working for him at the time, but they never went beyond the position of ordinary draughtsman. He was working on The Gates of Hell, a bronze door for the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, inspired by Dante’s The Divine Comedy and consisting of over 200 figures experiencing all aspects of suffering and passion. This became Rodin’s life’s work–in reality, his magnum opus. It is believed that Camille posed for several of the figures; in any case she did work on the hands and feet of several of his larger pieces. One of these artists, Jessie Lipscomb, arrived from England to join the studio in 1884. She lived with the Claudels and became a lifelong friend; her loyalty to Camille seldom wavered even throughout the difficult periods in Camille and Rodin’s relationship, and in fact, she often served as a kind of liaison between the two.

It is uncertain when Rodin and Camille became lovers, but it was possibly around 1883 or 1884. Both Camille and Jessie Lipscomb began working at one of Rodin’s several ateliers at 182 Rue de l’Université around 1885, and some believe the intimacy started that year. Since the 1860s Rodin had been living with his one-time model, Rose Beuret, whom he married in 1917 when both were close to death. Beuret served first as Rodin’s model, then as his housekeeper and studio assistant, and contributed to the household accounts by taking in work as a seamstress. They lived in Belgium for several years until the late 1870s, then returned to Paris. Rose was aware of Rodin’s dalliances with other women, in particular his models, but appeared to understand that a man of his temperament and creativity could not be expected to live the conventional life of a businessman or shopkeeper. Thus it was that Rodin was able to take Camille on as a protégée and mistress, but so as not to arouse Madam Claudel’s suspicions about her daughter, they acted discreetly. So discreetly, in fact, that Camille’s mother once invited Rodin and his “wife” (people referred to Rose as Madame Rodin) for a visit at Villeneuve.

The Bust of Madame B. was completed and accepted for the salon organised by the Société des Artistes Français held each year in May. Works that received the major awards were later purchased by the state, and government commissions were given to the winners. While the salon accepted many women’s works, they seldom won prizes, and then nothing more than honourable mentions.

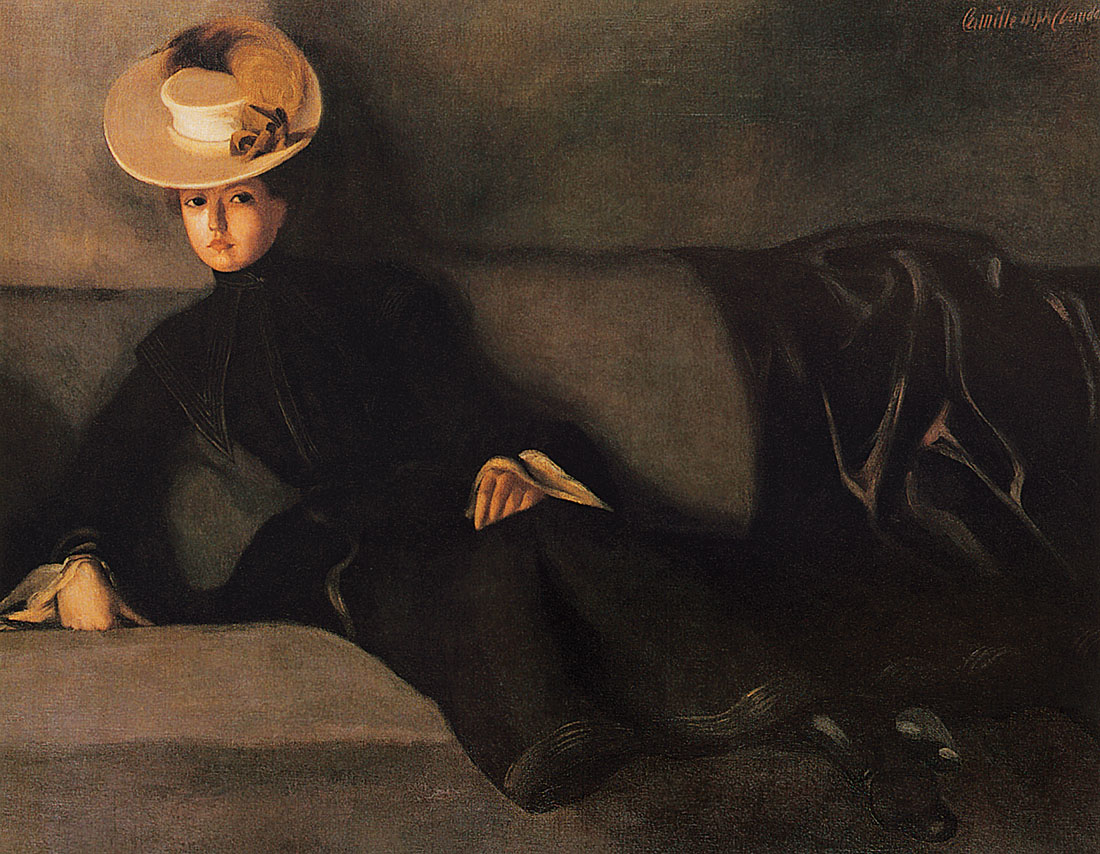

During the period from about 1884 to 1888 Camille and Jessie revelled in the rich, bohemian existence of Paris’s artistic community. When the girls were not working in the atelier they roamed the streets of Paris, delighting in the Louvre, the Luxembourg Palace and Versailles. In the afternoons they relaxed with tea and cigarettes, a daring activity for women at that time. Camille created a bust of her sister titled Louise Claudel in 1885, her brother-in-law Ferdinand de Massary (1, 2) in 1888, and Sakuntala (1, 2) in 1888. This last piece received an honourable mention at the Salon des Artistes.

There have been numerous debates about Rodin’s influence on Camille and vice-versa. Rodin constantly instructed his students to create hands and feet, believing that movement emanated from them. The most important aspect of the body was the profile, he once said; with each turn of the body, another profile is created. He also persuaded sculptors to exaggerate features with the idea that they could be modified later.

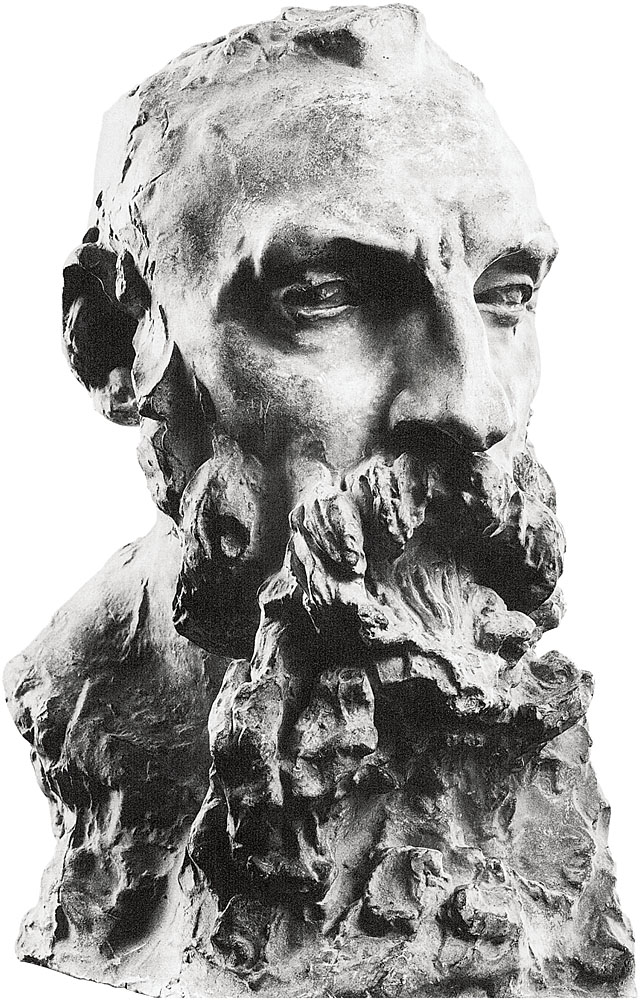

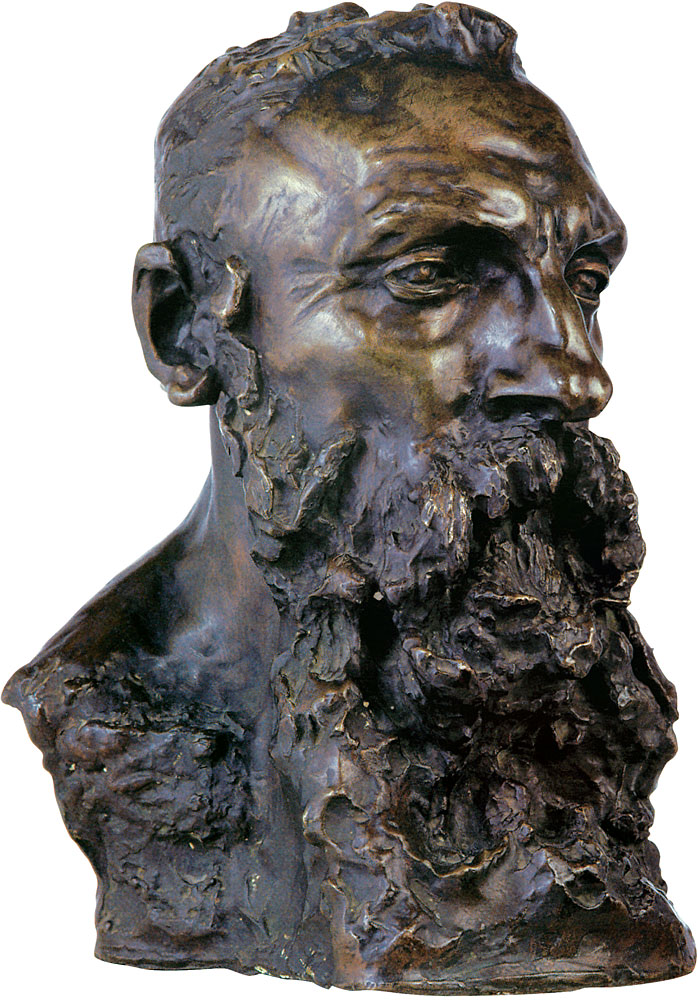

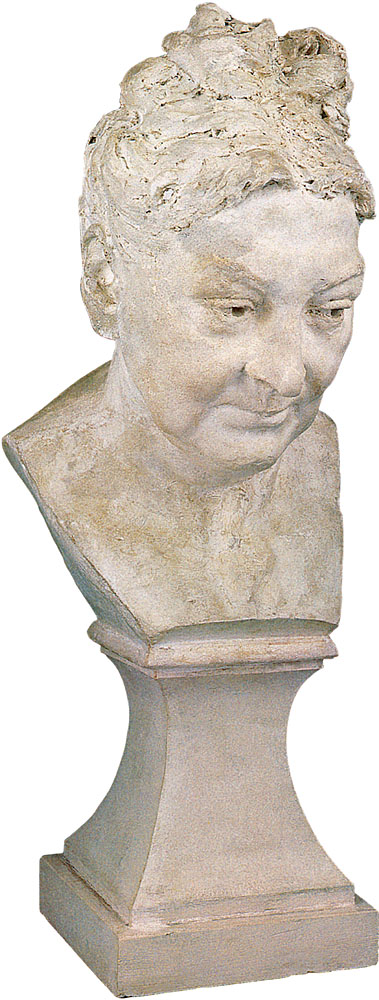

Bust of Auguste Rodin, 1888-1889

Bronze, Gruet casting (1892), 40 x 24.6 x 28 cm. Private collection

Rodin worked at several ateliers during his lifetime but he considered the one at 182 Rue de l’Université home. That is where Jessie and Camille prepared materials and armatures, enlarged or reduced maquettes and made studies for the larger sculptures, The Burghers of Calais and The Gates of Hell. Camille’s role in the studio was somewhat loftier than that of the other assistants. Jessie and the others “dressed” the figures–Rodin believed in creating the figure nude and then dressing it. Camille was trusted with creating the hands and feet, and Rodin often consulted her before making decisions on how to proceed with the figures.

In general the creative relationship between Camille and Rodin during that time was fairly casual insofar as who got credit for what. He often put the finishing touches to her pieces and signed them, as was the process in nineteenth-century Europe. Assistants knew this was a learning process; nevertheless, there was usually some confusion attributing the right work to the right sculptor.

Young Woman with a Sheaf (1, 2) and Galatea are good examples of this. Camille created Young Woman with a Sheaf around 1887; Rodin created Galatea perhaps a year or two later. Both show a young girl, seated, her right arm bent and covering her right breast. Her left leg is bent at an angle behind her; she glances slightly toward the right. Camille’s subject has a little more of the look of an ingénue; Rodin’s appears more mature. It is impossible to say whether or not Rodin drew from Camille’s creativity, or was the guiding force in her genius or if he created similar works to see if he could do better. That their relationship went beyond student and teacher or assistant and master only adds to the dilemma of who learned from whom or who exploited whom.

Once Camille and Rodin declared their love for each other, it was necessary for them to exercise discretion. Their mutual acquaintances, mostly other artists, treated the relationship casually, and seldom acknowledged it. After all, Rodin was living with Rose Beuret and Camille resided in the Claudel apartment at 31 Boulevard de Port-Royal. Furthermore, the vast difference in their ages (Rodin was 24 years older than Claudel) would have further added to the scandal.

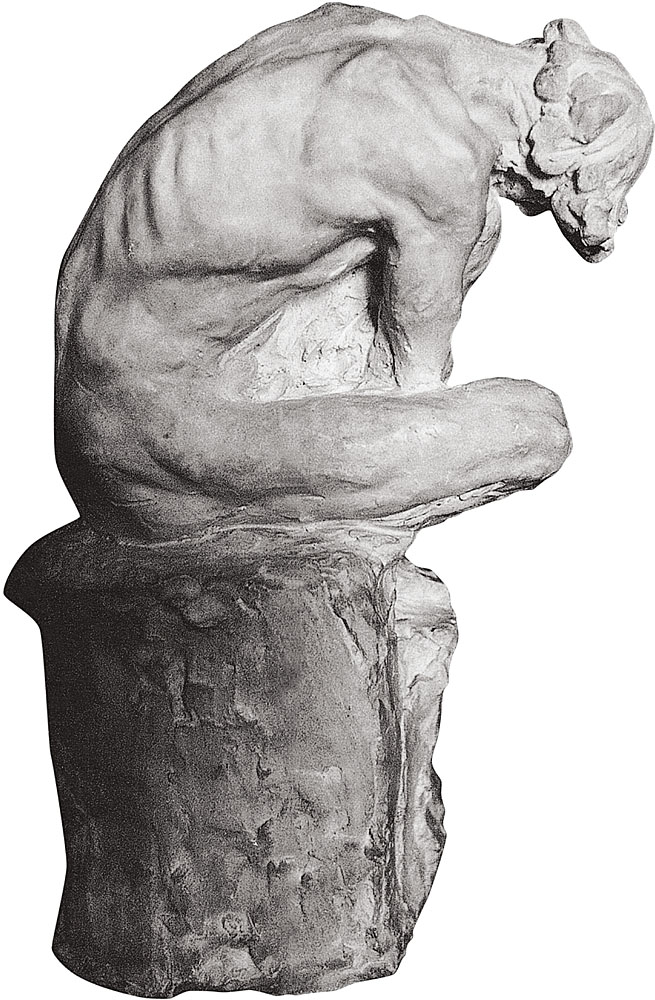

In any case, the mid-1880s was a prolific period for Camille. In 1884 she created Torso of a Crouching Woman in tinted plaster, showing a squatting figure, its powerful legs and feet straining to support the back. From this several bronzes were produced. Family members served as models from 1884 to 1886. Paul Claudel was the model for Young Roman or My Brother at Sixteen (1, 2, 3); Portrait of Louise-Anthanaise Claudel, an oil painting of her mother, has since been destroyed. Bust of Louis-Prosper Claudel, done most likely in plaster, has also disappeared. Louise Claudel, a terracotta bust of her sister, was created in 1885. Several versions of Young Roman remain today in both plaster and bronze. A Louise Claudel bust in terracotta is part of the Musée des Beaux-Arts collection in Lille and a bronze was donated to the Musée Bargoin, Clermont-Ferrand. Her Young Woman with Her Eyes Closed, done in terracotta, shows a more graceful side of Camille; the head turned slightly, its firm chin raised, the mouth slightly open as if waiting for a lover’s kiss.

The Waltz ‘with Veils’, 1892

Bronze, Siot-Decauville casting (1893), 96 x 87 x 56 cm. Galleri Kaare Berntsen, Oslo

The Gossips, study for version without walls, c. 1892-1893.

Bronze, cast posthumously, 23 x 29 x 26 cm. Musée Rodin, Paris

La Petite Châtelaine, version with curved plait, 1893

Patinated plaster, 33 x 28 x 22 cm. Private collection

Chapter Four

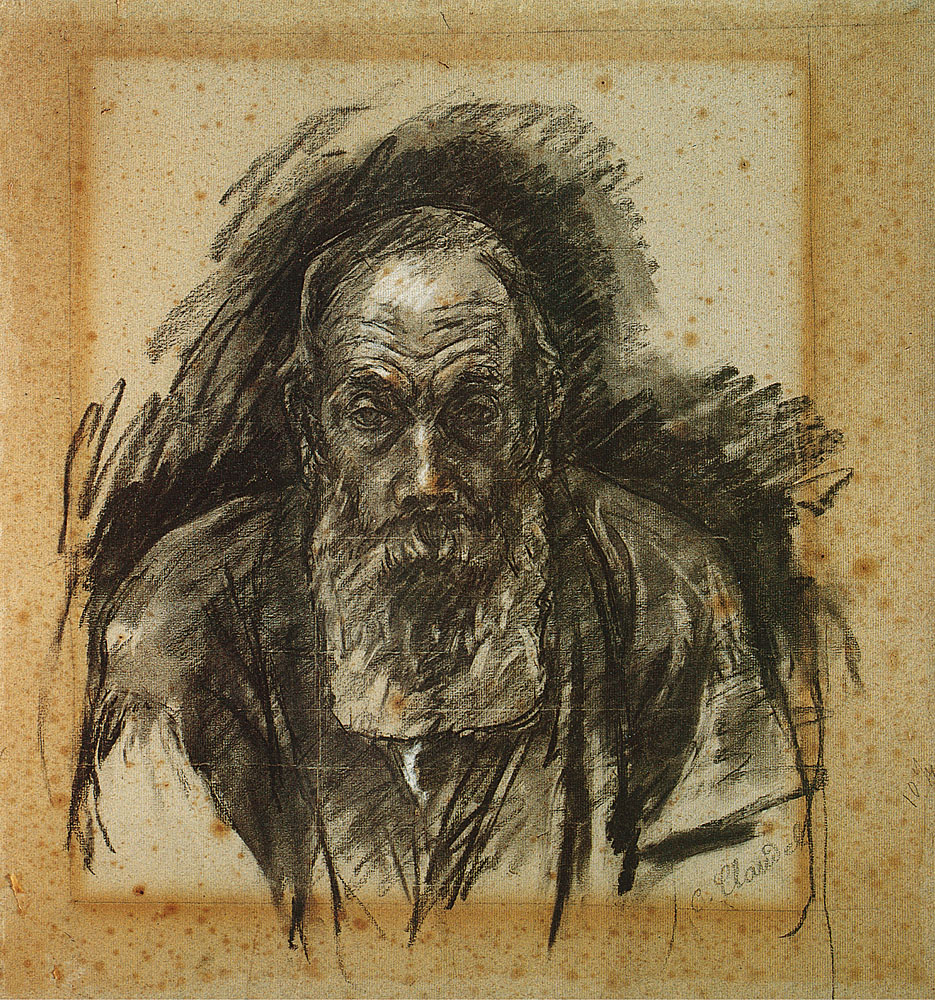

By 1885, as Camille worked on The Burghers of Calais, her own vision emerged as well. Her role in its creation provided the learning experience she needed. Works produced by Jessie Lipscomb at the time also show a resemblance to similar ones created by Rodin and Claudel, and this is partly due to the fact that all three used the same model, known as “Giganti”. Camille and Jessie each created a bust of him around 1885. Jessie’s version shows a truer likeness; it displays little emotion, as though the model were posing for a portrait. Camille’s Giganti shows more intensity in its features: the chin is raised, the mouth full but rigid, and the eyebrows knitted. The figure is unashamedly bold and self-confident. Along with Old Helen (Bust of an Old Woman), Giganti was exhibited in 1885 at the Salon. Several casts of the Camille Giganti exist in European museums, such as Cherbourg, Lille and Reims in France and in the Bremen museum in Germany. Curiously, the one in Bremen is signed by Rodin. There could be one of two reasons for this: Rodin admired it and wanted credit for it, or the signature was forged to make it more valuable as a Rodin rather than a Claudel. A plaster study of Giganti, found after Camille’s death, had served as a study for Rodin’s Avarice and Lust. The two figures in the sculpture also appeared in The Gates of Hell.

By 1886 the illicit relationship between Claudel and Rodin was obvious to everyone around them, save for their families. Camille, by this time, had developed her own style and was past the stage where she looked to her master for guidance. Some believed that it was he who sought her counsel in matters of art, although Rodin, his commissions growing, had reached celebrity status. Yet his involvement with Camille caused him untold anguish. The two quarrelled often, after which Camille would disappear. In an undated letter from Rodin to Camille he tells her how he spent a night searching for her in their favourite places, puzzled at her apparent disregard for his feelings. Jessie served as intermediary between the two lovers: Claudel’s capricious temperament bewildered the smitten Rodin, his ardour resembling that of a schoolboy experiencing his first crush. Rodin wrote several notes to Jessie asking about Camille, begging Jessie to bring her to him.

In the spring of that year, Jessie invited Camille to her parents’ home in England. The girls departed in May and returned the following September. Coincidentally, Rodin had plans to spend a week around the end of May in London visiting a friend. When the Lipscombs learned of this they invited him to spend a day at their home in Peterborough. Rodin readily accepted, anticipating a delightful reunion with the woman he loved. However, when Rodin arrived, Camille ignored him. Rodin stayed the night and left the next morning, disappointed.

Camille spent the remainder of the summer visiting another friend who had shared the studio in Paris, and in August Paul Claudel joined her and the Lipscombs on the Isle of Wight. Rodin thought she might return around the end of August, and invited her and Jessie to accompany him to Belguim after their arrival in Calais. But Camille refused because she was scheduled to exhibit Giganti at the Autumn Exhibition in Nottingham. However, she wrote to Rodin that she was unhappy in England and cautioned him to take care of his health. Yet she did not return to France until September. Of the works produced around 1886 and 1887, probably the best known are Portrait of Jessie Lipscomb, Young Roman (Paul Claudel at Eighteen), and several oil paintings including Portrait of Eugénie Plé (reproduced in L’Art décoratif, in July, 1913; now disappeared), Portrait of Maria Paillette, Portrait of Rodin Reading a Book (disappeared), Louise Claudel (Madame Ferdinand de Massary), Portrait of Victoire Josephine Brunet (disappeared) and another Portrait of Rodin.

La Petite Châtelaine, version with straight plait, 1893

Marble (1895), 33 x 28 x 22 cm. Private collection

Dog Knawing a Bone or Hungry Dog, c. 1893

Bronze, Alexis Rudier casting, 15 x 25.5 x 11 cm; (height with wooden socle: 20 cm). Private collection

The Gossips, first version with walls, 1893

Bronze with walls in marble (1905), 32 x 34 x 24 cm. Private collection

The Gossips, first version with walls, 1893

Bronze with walls, Eugène Blot casting (1905). Walls lost

There could be a number of reasons why Camille ran hot and cold in her treatment of Rodin. It may have been the start of her eventual mental breakdown, or she feared that their relationship would be discovered by her mother, causing an even greater rift in the mother-daughter relationship, which was tenuous at best. Madame Claudel wanted nothing more than for her daughter to live the life of a wife and mother. Yet Camille worked ceaselessly in Rodin’s atelier, posing for him and contributing to his projects. In 1886 he created Thought, the head of a pensive young woman done in terracotta, for which Camille was the model. Mounted on a slab of marble, the head appears to be sinking into the marble, the woman lost in her own musings, while imprisoned by her life or the life that has been chosen for her. In a sense it is chillingly prescient, foretelling Camille’s eventual incarceration in an asylum.

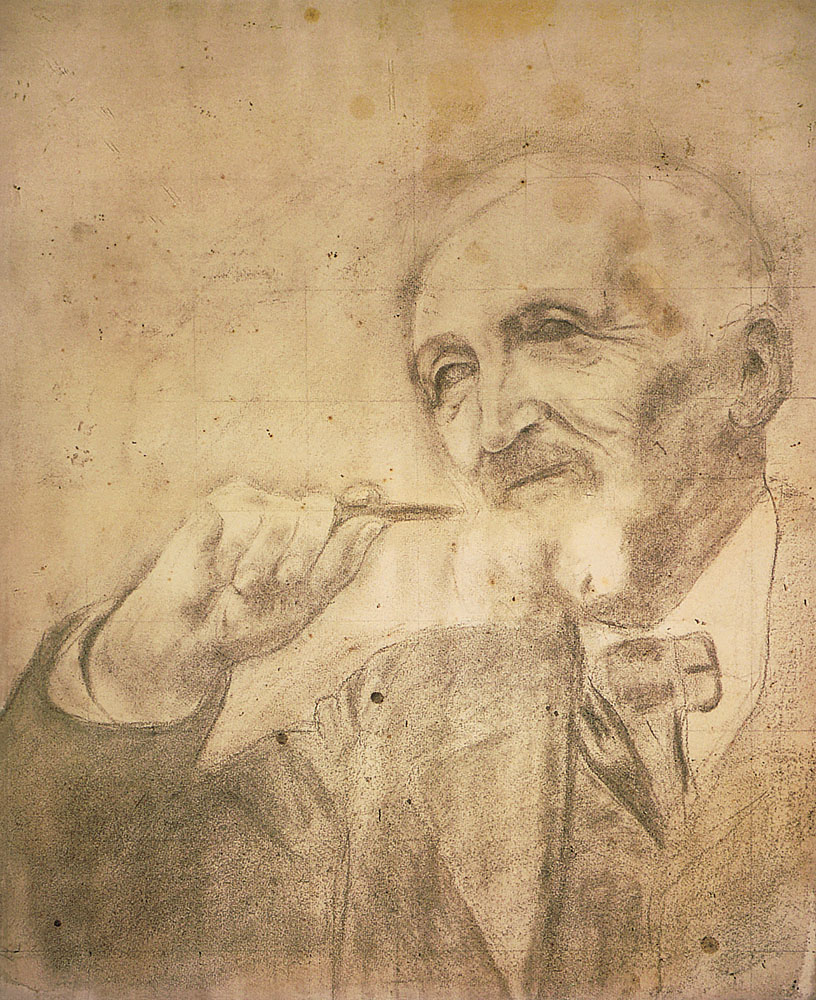

When Camille was not in one of her temperamental moods, she sought his help in furthering her career. She accompanied him to various society dinners, during which people referred to her as Rodin’s pupil. Rodin also contacted the people from the magazine L’Art and subsequently the art critic Paul Leroi wrote a piece complimenting Camille’s sculpture of her sister Louise. The article also featured drawings Camille had made when holidaying with her family in 1885: two women from the Vosges Mountains and a drawing of a nude. In 1887 he followed up with another review, this time of Young Roman, currently being exhibited at the Salon. Again, charcoal drawings were included in the article: three studies of elderly women and one of a friend’s father. Leroi praised Camille as a woman who was finally coming into her own artistic voice and vision.

Despite the uncertainty of Camille’s feelings, Rodin drew up a contract for her in October 1886. Among other things, he promised to have only her as a student, that his friends and connections were offered freely to her, that he would do everything possible to publicise her exhibitions; he intended to take her to Italy where they might live for six months, after which he would take her for a wife. Apparently, there were times that Camille pressured Rodin for marriage. Yet nothing ever came of the “contract”. She may have wanted something in writing showing he recognised her as an artist and a woman.

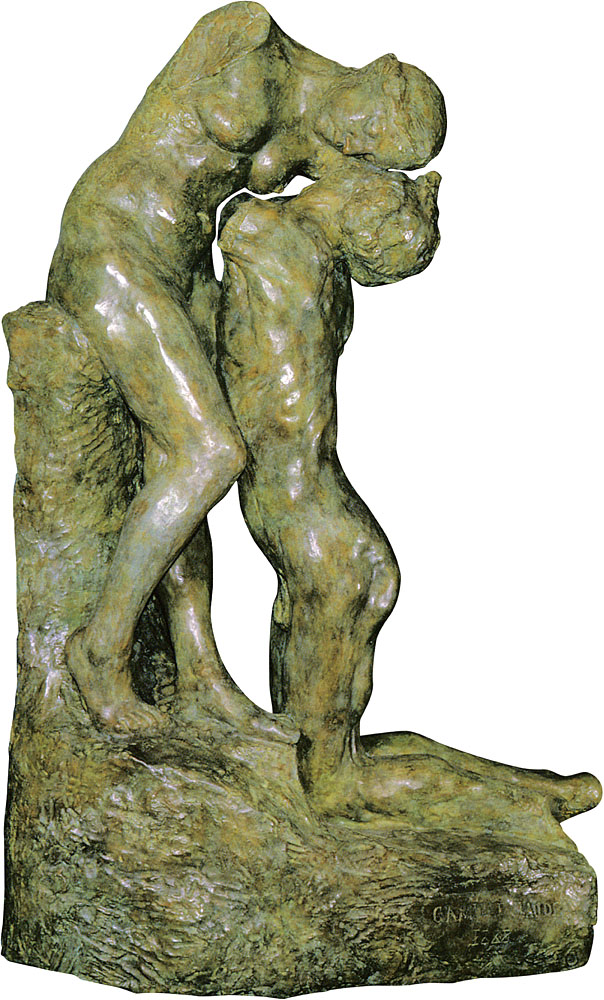

In 1887 Camille began her first large-scale work, Sakuntala. So caught up in the project, she spent her days shut up in her studio, often for twelve hours at a time. Consisting of two figures, a man and a woman, the sculpture was inspired by an Indian legend dramatised in Sanskrit in the fifth century. The story tells of a prince who, during a hunting trip, meets the daughter of a saint and a nymph who has been adopted by a hermit. The prince falls in love with her, they marry and he gives her a ring before departing for his castle, promising to return for her soon. One day the hermit, upset with Sakuntala, casts a spell on the prince causing him to forget Sakuntala unless he sees her ring. She departs for the palace, but loses the ring on the way while crossing a river. Unable to show it to him, she goes into the forest and gives birth to a baby boy conceived on the wedding night. A fisherman later finds the ring, brings it to the prince, who comes out of the spell and remembers the wife he left behind. In a happily-ever-after finish, he searches for Sakuntala and takes her back to the palace, making her his queen.

Camille’s sculpture shows the prince kneeling before the woman he loves, repentant of his forgetfulness as Sakuntala falls into his arms. Her arm modestly covers her breast as her head bends toward her husband’s forehead. The overall mood is one of tenderness, eroticism, joy, and adoration.

The Flying God (detail), second version, 1894

Bronze, cast posthumously, 69 x 56 x 38 cm. Private collection

The Gossips, first version, 1894

Bronze and marble, Eugène Blot casting (1905), 33 x 20 x 31 cm. Private collection

Head of an Old Woman, study for The Age of Maturity, c. 1894

Plaster, 11 x 7.5 x 10.5 cm. Private collection

In September of that year, after Camille had spent a quiet summer with her family, she and Rodin took their first trip together to the Loire Valley. The trip to Italy promised in his “contract” never materialised, and any discussion of marriage seemed to have evaporated. Camille became moody and petulant, at the same time employing a little coquettishness. It is possible that, in an attempt to placate Camille, Rodin had offered her a few days with him at the château of Islette in Azay-le-Rideau, and this became the first of many trips to the château.

By that time it had become impossible for Camille to keep her liaison with Rodin secret. Paul knew of it, and, since he had converted to Catholicism in 1886, his sister’s indiscretion seriously affected his sensibilities. Camille had no choice but to move out of the family home. She took a small apartment at 113 Boulevard d’Italie and in January 1888 Rodin paid the first year’s rent.

That same year Rodin established another atelier at 68 Boulevard d’Italie, just a stone’s throw from Camille’s home. It was reputed to have been the meeting place of the poet Alfred de Musset and George Sand. Although the property could charitably be described as “dilapidated”, it was one of Rodin’s more favoured ateliers. It was overgrown with vegetation on the outside, and inside the house many areas were uninhabitable due to crumbling walls. But it afforded a certain amount of privacy for Camille and Rodin and, best of all, it was located far enough away from the house he shared with Rose.

The plaster version of Sakuntala was completed in time for the 1888 Salon and received an honourable mention, as well as high praise from several critics. Other renditions of Sakuntala were created over the years; a marble version in the early 1900s was re-named Vertumnus et Pomona, signifying the mythological couple Vertumnus and Pomona, guardians of fruit trees, and a reference to the statue of Pomona that decorated the dilapidated atelier Camille had shared with Rodin. Later, two bronze editions – one large and one small – were financed by Eugène Blot. Other works created that year included the Bust of Auguste Rodin (1, 2), Profile of Auguste Rodin (a bas relief), Study after Nature (charcoal), Paul Claudel at Twenty Years Old (coloured pencil), Torso of a Standing Woman (plaster), and Ferdinand de Massary (husband of Camille’s sister Louise).

Rodin struggled to complete The Gates of Hell in time for the World Exhibition of 1889 but failed to make the deadline. Instead, he and the painter Monet assembled a joint retrospective at the Georges Petit Gallery in June. The work required to assemble the exhibition coupled with the disappointment at his inability to finish The Gates of Hell left Rodin exhausted and short-tempered. Nevertheless, the show was successful for both men: Monet exhibited 145 paintings and Rodin’s thirty-six sculptures in the show included the final version of The Burghers of Calais. Camille began work on two more sculptures following the Salon exhibition. One was Bust of Charles Lhermitte, son of Léon Lhermitte, the painter. It shows a pensive young boy, hair tumbling to his shoulders, staring. Yet one senses a pent-up energy, as though he wonders when he will no longer be forced to sit still. While it did not possess the intensity of Sakuntala, it was received well by the critics at the World Exhibition in 1889. She also began sketches for a larger piece, a group of waltzers.

That summer, Rodin slipped away to the south of France and then to Spain, although no one, including Rose, knew of his whereabouts. Camille apparently accompanied him, although she had fabricated a story to her friends indicating that she had plans to serve as a governess for a British family during their travels on the continent. The couple travelled for two months, returning to Paris in September. Camille intended to throw herself back into her work schedule. In addition to the bust and group sculpture she had also received what should have been her first commission, a sculpture of the republic to be placed on the fountain in her birthplace, Fère-en-Tardenois. But when the historian who originally commissioned the piece presented the proposal to the village’s conservative council members, they rejected it. A sculpture created by a woman was totally unacceptable. Strangely enough, Camille seemed to take the rejection in stride and continued with her other two projects.

The ‘Frits Thaulow’ Waltz (recto), c. 1895

Patinated plaster, 43 x 39.5 x 18.5 cm. Private collection

The ‘Frits Thaulow’ Waltz (verso), c. 1895

Patinated plaster, 43 x 39.5 x 18.5 cm. Private collection

La Petite Châtelaine, version with straight plait, 1895

Marble, 44 x 34 x 30 cm. Michel Toselli Collection, Paris

La Petite Châtelaine, version with loose hair, 1895

Marble, 44 x 34 x 30 cm. Private collection

The Waltz, 1896

Flambé stoneware, 40.5 x 37.5 x 18 cm. Private collection

The Gossips, second version with walls, 1896

Plaster, 40 x 40 x 40 cm. Musées d’art et d’histoire, Geneva

The Gossips (detail), second version with walls, 1896

Plaster, 40 x 40 x 40 cm. Musées d’art et d’histoire, Geneva

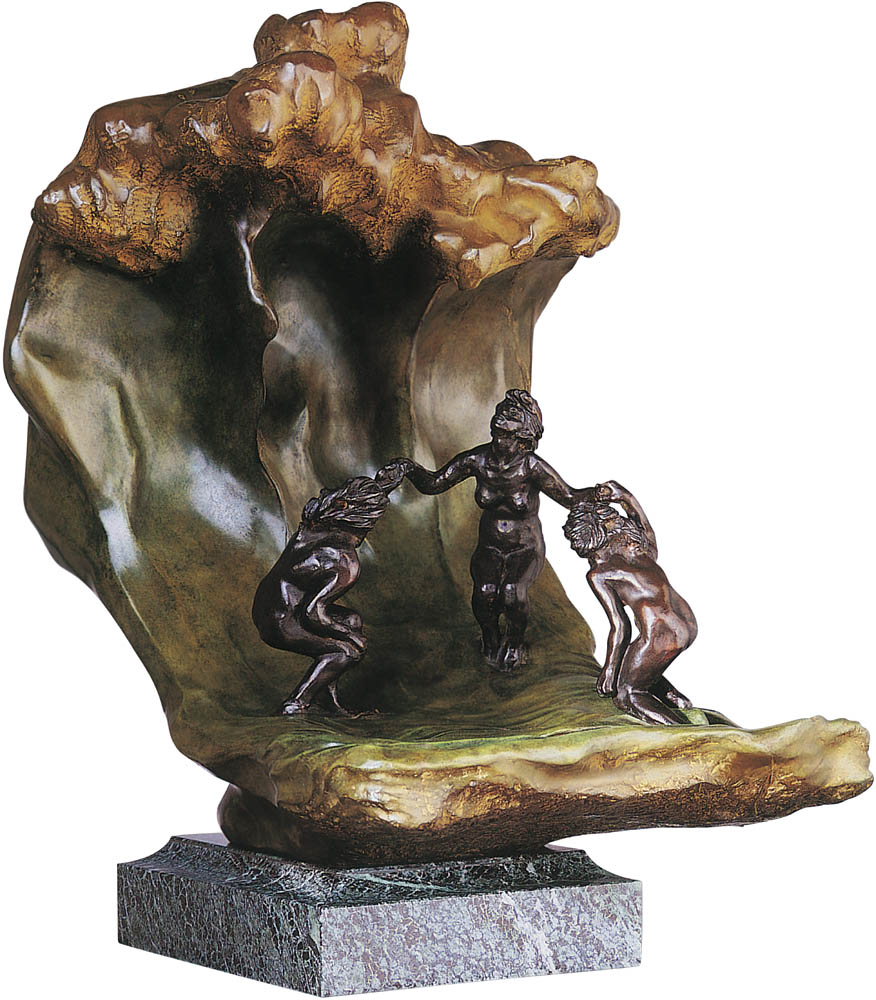

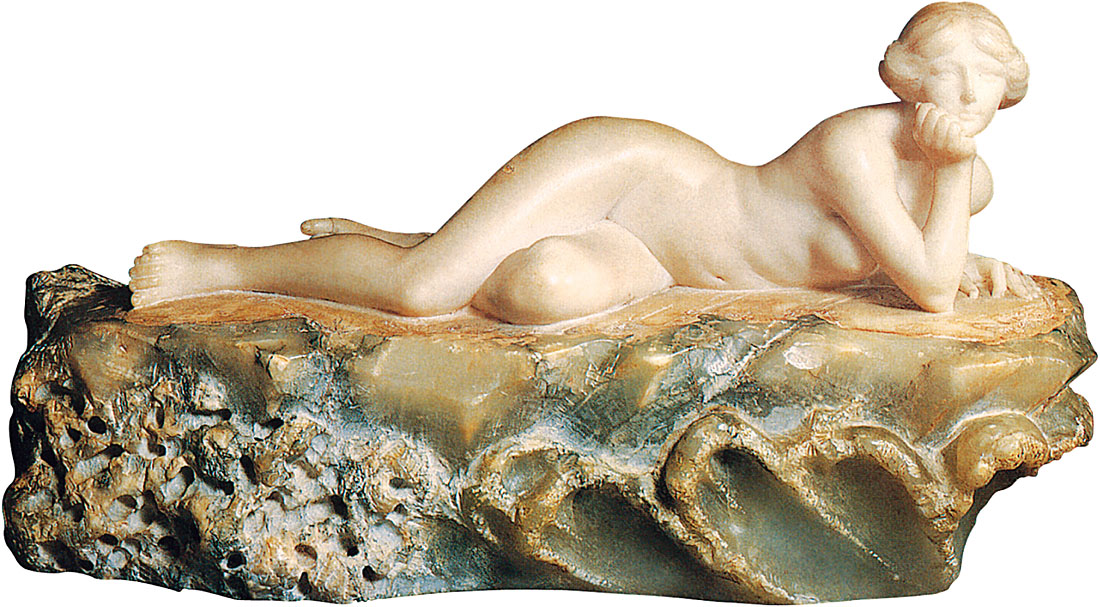

The Wave or The Bathers, 1897

Onyx and bronze on marble socle (1898-1900), 62 x 56 x 50 cm. Musée Rodin, Paris

Chapter Five

The World Exhibition of 1889, in which Gustave Eiffel’s tower dominated the horizon, was more than just a festival honouring the centenary of the French Revolution. People from all parts of the world were given a glimpse of cultures they had only read about in books. One experienced the resplendence of an African bazaar, the colourful precision of the Far East theatre, and the strange tastes and smells of foods with unfamiliar names. Many Parisians, however, were embarrassed by the metal skeleton that dominated the fair’s landscape. The Eiffel Tower, so symbolic of France today, was considered a monstrosity when it was first unveiled.

Claudel and Rodin both exhibited at the fair, but neither of their works were ones that defined their artistic careers. Rodin exhibited many of the pieces that resembled those in the Monet/Rodin retrospective. Camille’s work consisted of the Lhermitte sculpture, which, although it received positive reviews, was noticed by only a few critics.

The years 1889 to 1892 apparently were not as productive for Camille as other periods. She made several trips to Islette, sometimes alone, sometimes with Rodin. She did not participate in the Salon in 1890 or 1891. In 1889 Rodin took part in founding the Société des Beaux-Arts and became its sculpture president. Camille served on the panel of judges for its exhibition. In 1891, Rodin received a commission to do a sculpture of the writer Honoré de Balzac. To follow Balzac’s traces and get inspiration for the piece, Rodin and Camille travelled in Anjou and Touraine.

In 1892 Camille’s Bust of Rodin was cast into bronze after nearly four years of sporadic moulding and shaping, only to have the piece dry up as Rodin posed intermittently and then for very short periods of time. At one point, Camille took a fresh mould, completed the bust and after the bronze was cast, exhibited it at the 1892 Salon, now located at the Champ de Mars. Her efforts were well received by the critics; many viewed it as the perfect homage to Rodin. Every feature exhibited a strength of technique from the well-formed temples to the firm nose, expressive eyes and the detail in the beard.

That year also saw the completion and exhibition of the bronze version of The Waltz, the piece conceived several years earlier. The sculpture itself generated a story full of political deliberations, arguments and artistic interpretations, replete with moral overtones. For years, Camille, an artist skilled in working with marble, had requested a commission for a marble sculpture from the French government. She was convinced that the half life-size waltzers would be best expressed in marble. The Minister of Fine Arts ordered Inspector Armand Dayot to view the work and give his evaluation. Davot, upon seeing the piece, became somewhat nervous at what he felt were definite sexual overtones, and in his report, recommended that the semi-nude figures be clothed in heavier garments. As it was, he stated, the waltzers were “heavy” and the clothing too light. Although Rodin tried to defend Camille, his efforts went unheeded. But Dayot was adamant, saying that his main concern centred around the “closeness of the organs”, and suggested she make changes to the composition. Camille agreed, and during the next few months she did drapery studies on the group and once again submitted the changes to Dayot. The request for marble was approved by the Minister of Fine Arts but before a letter could be sent to Camille giving her the good news, Henry Roujon, the Director of Fine Arts, decided to hold off. He felt that there were still problems with the propriety of the work. It was one thing to award a commission to a woman artist, but a woman who portrayed obvious sensuality in her work had overstepped her bounds. During the next few years others tried to intervene on her behalf, but Roujon refused to budge.

The Wave or The Bathers, 1897

Bronze, posthumous casting (1989), 60 x 47 x 60 cm; (height with socle: 68 cm). Private collection

Woman Reading a Letter or Woman at Her Dressing-Table, 1897

Plaster, 38.5 x 39.5 x 28 cm. Private collection

Perseus and the Gorgon, 1897-1902

Marble (1902), 196 x 111 x 90 cm. Assurances Générales de France Collection

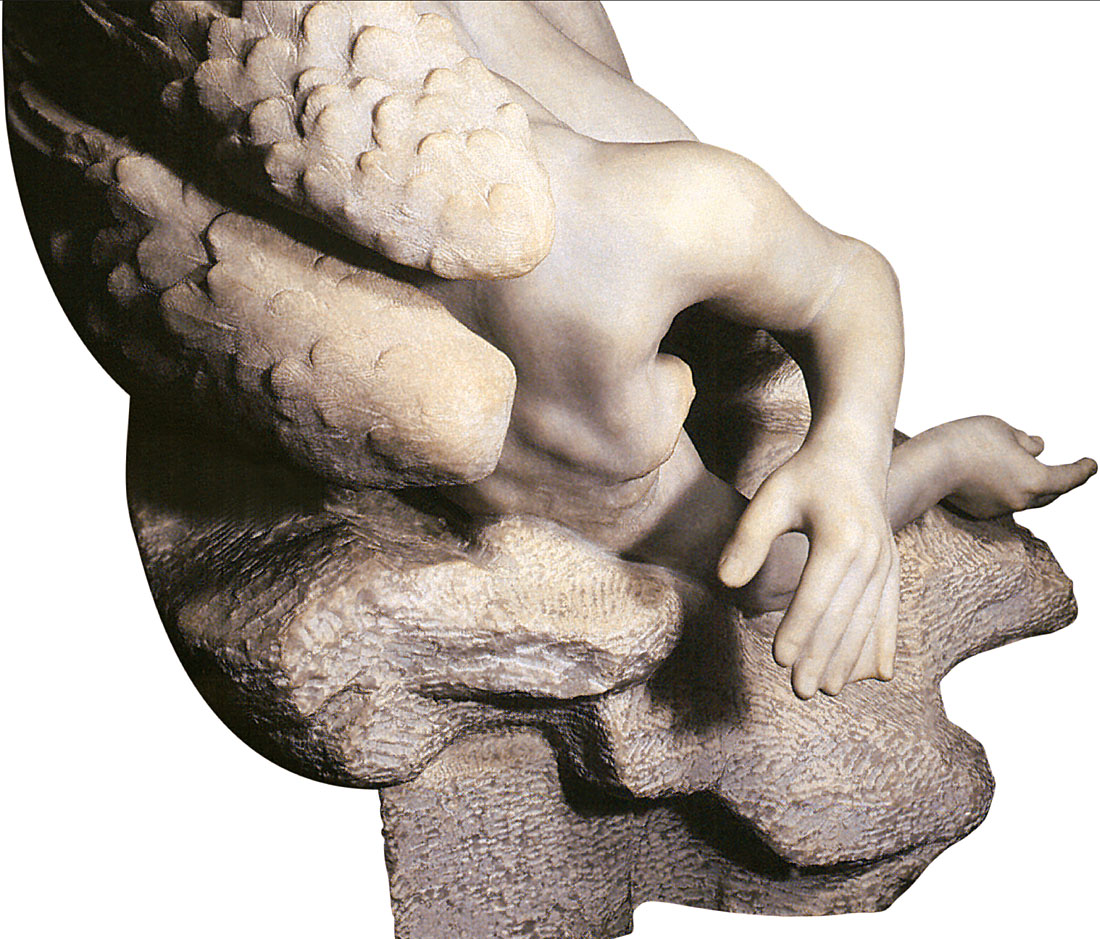

Perseus and the Gorgon (detail), 1897-1902

Marble (1902), 196 x 111 x 90 cm. Assurances Générales de France Collection

Perseus and the Gorgon (detail), 1897-1902

Marble (1902), 196 x 111 x 90 cm. Assurances Générales de France Collection

The Age of Maturity (recto), second version, 1898

Small model, Bronze. Eugène Blot casting, 61.5 x 85 x 37 cm. Private collection

The Age of Maturity (verso), second version, 1898

Small model, Bronze. Eugène Blot casting, 61.5 x 85 x 37 cm. Private collection

The Age of Maturity (detail), second version, 1898

Small model, Bronze. Eugène Blot casting, 61.5 x 85 x 37 cm. Private collection

The Age of Maturity (detail), second version, 1898

Small model, Bronze. Eugène Blot casting, 61.5 x 85 x 37 cm. Private collection

Fortunately, when The Waltz was exhibited at the Salon, the critics gave it high praise. They were struck by its emotion, the spirit in the figures themselves, and the feelings of adoration so evident in the movements of the lovers. Other smaller versions of the sculpture were created in its original “uncovered” state. The composer Claude Debussy had placed one of these on his mantelpiece, and this, plus Camille’s and Debussy’s mutual appreciation of art and music, led to their close friendship and gossip in the creative community that perhaps they were also lovers. The exact relationship between Camille and Debussy is uncertain. They met around 1888 and both were frequent visitors at the home of his friend Robert Godet. In any case the two had mutual interests and passions: Debussy enjoyed Javanese music and Camille Japanese art. Debussy had little use for Rodin’s work, which he viewed as overly sentimental, apparently ignoring the fact that so many saw a strong Rodinesque influence in Camille’s sculptures.

In 1893 Camille also exhibited Clotho, and while Debussy admired Claudel’s work, he may have felt she had gone too far with this one; for him, the work expressed an underlying feeling of malevolence, and it may have struck fear in him. In Greek mythology Clotho and her two sisters weave the fate of man. Camille created a wizened, bony woman trapped in the twisted threads of the lives she was weaving. The head is trapped among the threads as she reaches out trying to disengage herself. Both The Waltz with its tenderness and Clotho with its tortuous agony inspired strong feelings in Camille’s enemies and admirers. But even praise for her work was couched in phrases that drew attention to the fact that she was a woman. The critic Octave Mirbeau, in Ceux du Champ de Mars, (May 1893) said that her sculpture was “so male a conception that we pause quite surprised in front of this artistic beauty coming from a woman.”

During this period a strain began creeping into Camille and Rodin’s relationship. Rose knew of the liaison and launched into a tirade as soon as he walked in the door at their house on Rue des Grande-Augustins. Camille saw Rose as a shrewish old woman, expressing her hurt and anger in malicious cartoons depicting Rose as a bony old woman determined to keep her man trapped at home. In one (Waking up, Mild Reprimand by Beuret), Rose is poking Rodin in the chest as though she’s scolding him. In another (The Jail System), Rose carries a broom as she marches back and forth guarding the jailed Rodin, who sits huddled in chains. Both women worried that Rodin would leave them, but he wanted the best of both worlds–one woman to cook and care for him and the other with imagination in lovemaking as well as a match for him intellectually. Even though he believed he could keep both at bay by giving the same type of gifts to each of them, it did not work. Camille began severing relations with Rodin when, early in 1892, she moved out of the old mansion on Boulevard d’Italie and took an apartment near the Eiffel Tower; although she kept the atelier at 113 Boulevard d’Italie. That summer she travelled to Islette alone. There were rumours that at some time during this period Camille had an abortion; this appears certain because Paul Claudel in a letter of 1939, to a friend who had also had an abortion, refers to a person close to him who had killed a child and was paying for it in a home for the insane.

While at Islette, she began work on La Petite Châtelaine (1, 2), a bust of a six year-old girl, the granddaughter of the castle’s owner. The piece took two summers to complete, but the result is a child with an expression of innocence, curiosity and wonder. In addition to the plaster (1, 2, 3) and bronze versions of the bust, Camille also created four marble pieces as well (1, 2, 3). Her talent at carving in marble surpassed that of many artists of the time. While the earlier pieces in plaster depicted the girl’s hair fashioned into a braid in the back, a marble version exhibited in 1896 showed the individual strands of hair; the head was hollowed out to allow for light to move over the face.

Count Christian de Maigret in the Costume of Henry II, 1899

Marble, 66 x 65 x 43 cm. Private collection

The Implorer, 1899-1900

Large model, bronze, Eugène Blot casting (1905), 62 x 65 x 37 cm. Private collection

Chapter Six

The period from 1892 to 1903 marked a time of independence and heightened creativity for Camille. Gradually she severed her connection to Rodin, other than accepting his support in her professional life. She roamed the streets of the working-class neighbourhood surrounding the atelier, gazing at scenes of people engaged in everyday activities, and, upon her return to the studio, opened her sketchbook and quickly drew pictures of the sights she had witnessed: “Three men in new outfits perched upon a high cart on their way to Mass”; parents staring at their daughter, a young woman crouched on a bench, crying, or small people around a large table listening to prayer before a meal. To prove that she was now her own woman, Camille deliberately took her sculpture in other directions from Rodin; his figures were nude–hers were clothed; he worked large, her creations were small.

In a spirited letter to Paul she mentioned the works she had planned to send to the 1894 Salon in Brussels: La Petite Châtelaine, The Prayer or Psalm, The Waltz and “the little group of lovers”. This last is not mentioned in the Brussels catalogue; another, First Steps, is listed, but has disappeared. She threw herself into a grander project, a three-figure group titled The Path of Life, or The Age of Maturity (1, 2, 3, 4) which was also intended for the 1894 exhibit but was not completed until several years after. It showed a middle-aged man carried along by Old Age, sadly leaving Youth, who is represented by an imploring young sylphlike woman begging her “lover” to stay. Some interpreted it as Camille pleading with the ageing Rodin to come back to her as he was forcefully carried off by the wizened Rose Beuret. Meanwhile, she chose to concentrate on the figure of Youth and exhibited it as The Implorer, showing a woman (nude, even though Camille had stated her figures from then on would be clothed), kneeling and reaching out to that which is lost–possibly symbolising both Cupid and Rodin.

But Camille’s finances by this time were in severe straits. Paul sent her some money and, thanks to the efforts of Rodin and journalist Mathias Morhardt, a marble version of Clotho was commissioned by a group in charge of celebrating the seventieth birthday of the artist Puvis de Chavannes. In honour of Chavannes the committee donated the sculpture to the Musée du Luxembourg.

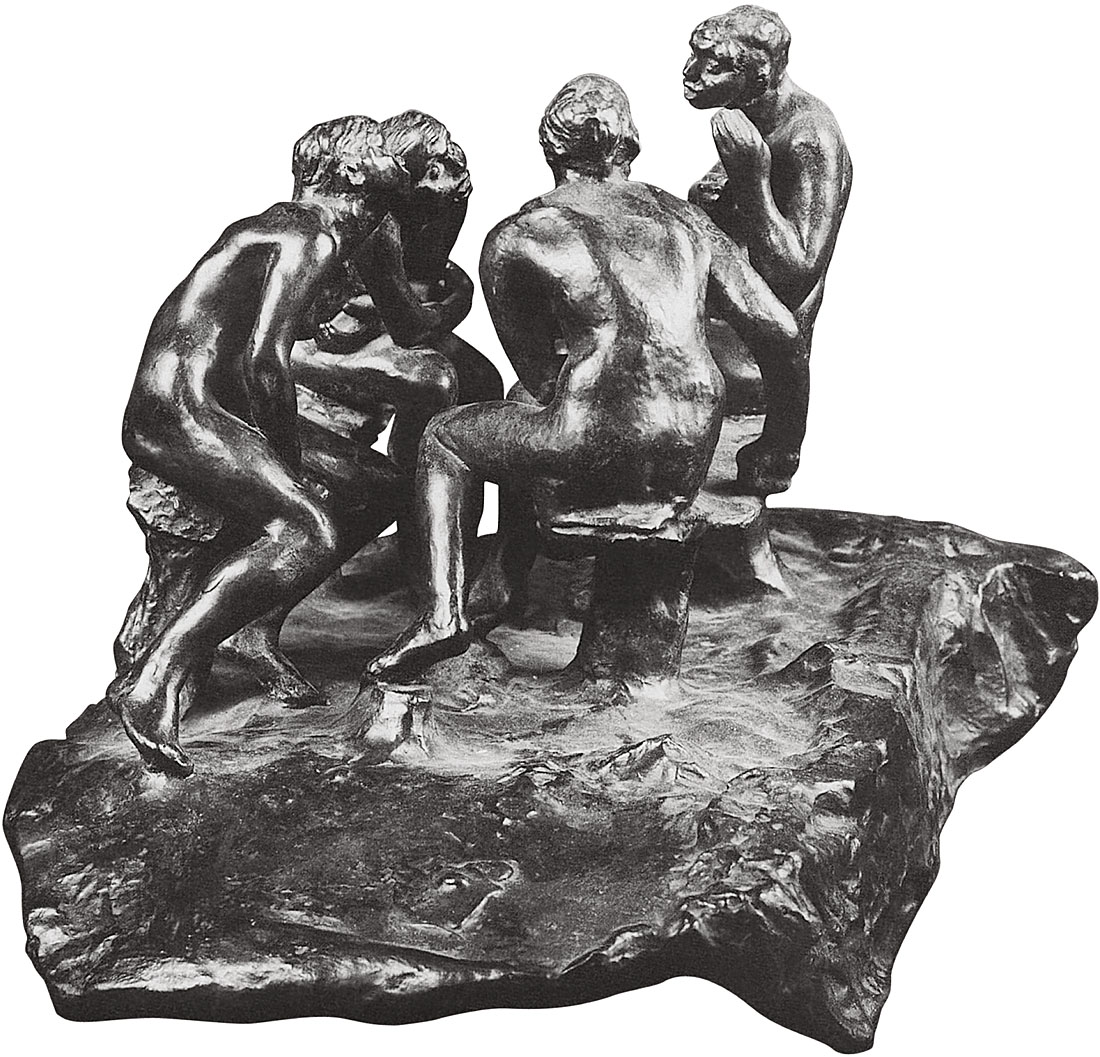

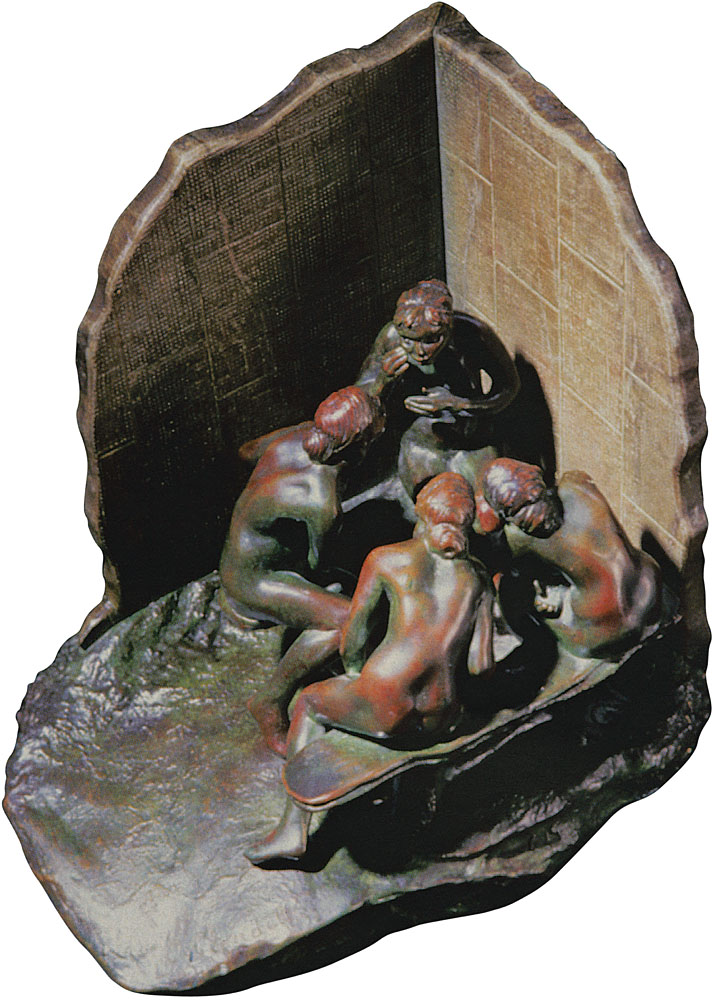

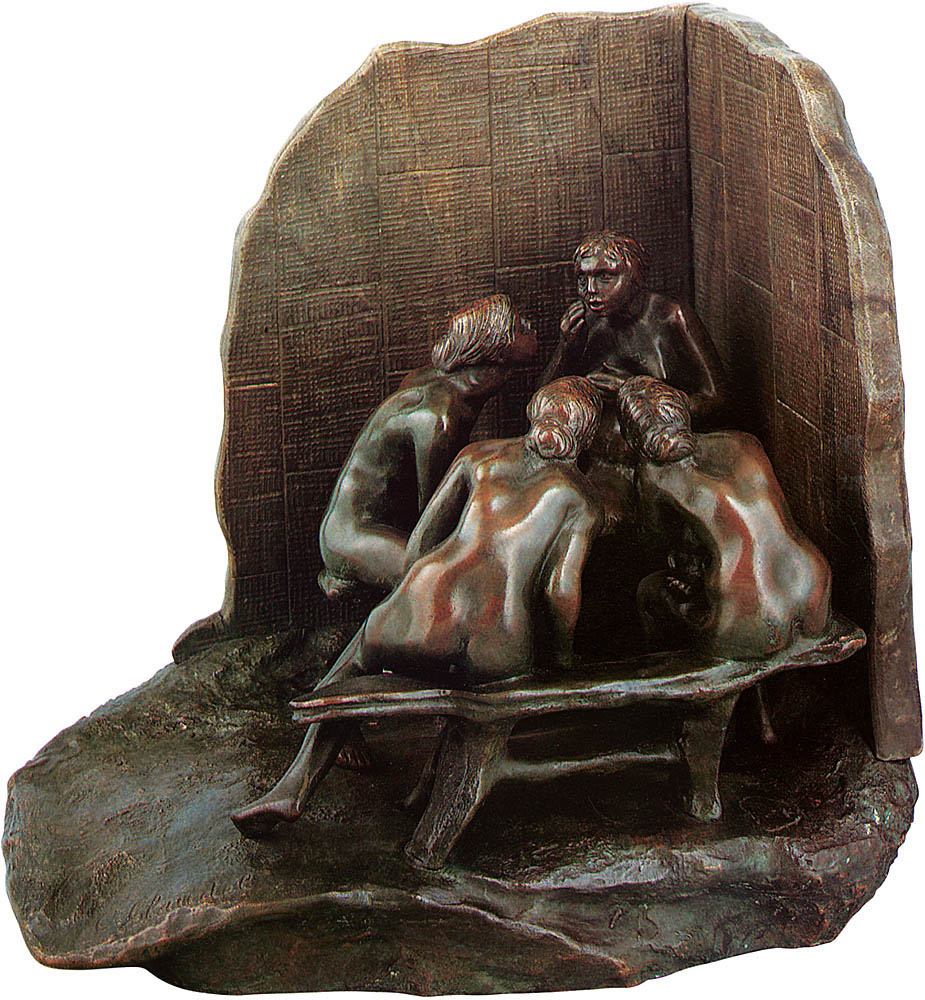

Camille could now breathe a little easier and turned her attention to her next project, The Gossips (1, 2), represented by a little sketch in a letter to Paul. The inspiration for this work came from Camille’s observation of four women chatting during a train ride. The figures are gathered behind a screen, listening intently to the speaker, apparently hungry for morsels of scandal, intent on every word. The piece was so well received at its showing at the Champ de Mars in 1895 that a number of versions resulted: both with and without a screen, in plaster, bronze, marble and green onyx.

The public’s reaction to this work and a magazine article praising her abilities and subtly asking why the Ministry was not begging for more masterpieces pushed Camille into the spotlight. Rodin, who still kept watch on her progress from a distance, was pleased and worked behind the scenes, writing to critics and arranging a meeting between her and the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Art in an effort to get her more commissions. In July 1895 the art inspector came to her studio with a commission for a bust but Claudel instead asked for a chance to complete the plaster of The Age of Maturity for 2,500 francs. The sculpture’s strongly hinted reference to Camille’s preoccupation with Rodin’s struggle to keep his youth as old age takes over was not lost on the ministry. Ironically, Camille’s first state commission, engineered by Rodin, also threatened to offend him by revealing his private anxieties.

The Wave or The Bathers, 1897

Bronze with green and brown patina, 58.4 x 45.7 x 61 cm. Museo Soumaya, Mexico City

Truth or Truth Emerging from a Well, 1900

Bronze, posthumous casting, 48 x 32 x 19 cm. Private collection

By now, Camille’s own style had begun to emerge. She gave her large plaster of Sakuntala to the Châteauroux museum in 1895, and although the work was praised by the art committee and critics, the local bourgeois ridiculed it and criticised the cost. She explored the psychological aspects of everyday life. Close on the heels of The Gossips were The Deep Thought (1, 2) in 1898 and the Old Blind Man Singing. The Wave or The Bathers (1, 2), in plaster, was exhibited in 1897 and a bronze and onyx version produced in 1898. While some works produced during that time have disappeared, we know that she created several portraits including: Léon Lhermitte (1894), Count Christian de Maigret in the Costume of Henry II (1899), Paul Claudel at Forty-two Years of Age (1910), several Children’s Heads (1, 2) and The Alsatian Woman (1902). Commissioned works were Hamadryad (1897) and Perseus and the Gorgon (1897-1902). Fortune and The Flute Player were completed prior to 1905 but by then, even as her vision blossomed, her mental state began to deteriorate.

Holed up in her studio between 1893 and 1913, Camille saw few people, worked unceasingly, and travelled little, except to Guernsey in 1894 and to the Pyrenees with Paul in 1905. There was occasional contact with Rodin up until 1898, but Camille preferred that Mathias Morhardt act as an intermediary until she finally asked Morhardt to tell Rodin to stay away. And yet Rodin continued to help further her career, although often she was unaware of his efforts. He worked to bring her commissions, wrote a letter of thanks to critics who defended her during the Châteauroux incident and offered to introduce her to influential politicians. She refused, with the excuse that she had nothing to wear.

During this period she was in a constant state of near poverty. Her father and brother helped financially, for although she was admired by her fellow artists, she received less formal recognition in the form of commissions, though it is possible she may have designed objects such as lamps and ashtrays.In addition, sculpture materials (marble and clay) and workmen (casters and models) were expensive. The debts piled up, year after year. She continued to exhibit, however, at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, the Salon d’Automne or the Salon des Indépendants in addition to showing at the Bing and Eugène Blot galleries. Her work appeared in Brussels in 1884 and at the Exposition Universelle in 1900. Critics and collectors became interested in her work, yet she often ignored the possibility of acceptance into society, preferring instead to pursue her own explorations in art and sculpture. Rodin’s fame soared and she may have felt pangs of jealousy at her lover’s success.

The bitterness between Camille and Rodin was further exacerbated when, in May 1899, The Age of Maturity was exhibited in plaster (one month later, the ministry had commissioned a bronze casting of the piece, then abruptly cancelled it for unknown reasons), along with Clotho, Countess Christian de Maigret and Perseus and the Gorgon. When Rodin spotted The Age of Maturity and saw it as a public exposition of his private life, he was hurt and furious. This spelled the end of any friendship he still felt for his former mistress. She, in turn, saw him as someone who had set out to damage her career and reputation.

Camille continued to battle with the French government over the cancelled commission for the bronze version of The Age of Maturity. Eventually, a captain in the French army, Louis Tissier, commissioned a bronze of the kneeling figure in the group, and later the entire sculpture was cast in bronze and exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1903.

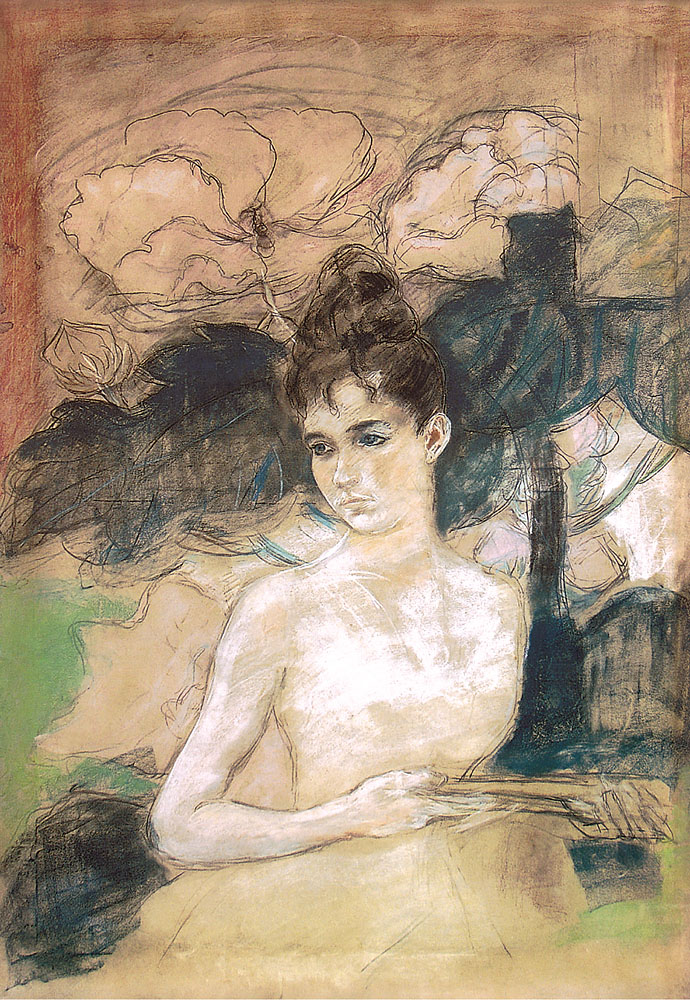

Countess Arthur de Maigret, 1903

Charcoal with chalk and pastel highlights on paper, 53 x 66 cm. Musée Municipal, Château-Gontier

The ‘Eugène Blot’ Waltz (detail), 1905

Large model, bronze, 46.4 x 35.7 x 19.7 cm. Private collection

The Waltz, 1905

Small model, gilded bronze, Eugène Blot casting, 23.5 x 16.5 x 10 cm. Private collection

Deep Thought, 1905

Bronze and marble, Eugène Blot casting, 24 x 22 x 27.5 cm. Galerie Odermatt-Cazeau, Paris

Abandonment, 1905

Small model, bronze, Eugène Blot casting, 43 x 36 x 19 cm. Fondation Pierre Gianadda Collection, Martigny (Switzerland)

She left her studio at the Boulevard d’Italie in 1896, moved to 63 Rue de Turennne, then moved to the Ile-St-Louis to 19 Quai Bourbon where she lived the life of a recluse, creating a marble version of Sakuntala (renamed Vertumnus et Pomona), The Deep Thought and The Dream by the Fire. Other works included Dawn (two, both marble, 1, 2), The Wounded Niobe (in plaster). Several magazines wrote articles admiring her creative genius, her ability to pursue her craft in the face of poverty and discrimination against female artists. A number of works produced during this time have disappeared, and, according to a friend, Henry Asselin, she regularly destroyed her work from about 1905 on. Once the debris and dust were carted away, she would disappear for months at a time. In 1908 she exhibited for the last time in her lifetime at Eugène Blot’s gallery. From then on she kept herself shuttered in the first floor rooms on Quai Bourbon, seeing no one. Her family, except for Paul Claudel and her father, had shut her out of their lives. She avoided her friends, and after a while, no one came to see her any more. Surrounded by chunks of material that had once served as an homage to her genius, she lived for the next few years in disarray, bleakness and solitude.

Finally, in 1913, following the death of their father, Paul Claudel felt he had no choice but to send Camille to the Ville-Evrard mental hospital near Paris. The next year she was transferred to the asylum at Montdevergues in the south of France, where she stayed until her death in 1943. During those years, her only visitors were her brother Paul and her old friend Jessie Lipscomb Elborne (who, along with her husband, stopped by in 1929). Her mother sent letters occasionally, some to the administrators of the asylum, requesting special treatment for her daughter, and some to Camille, but those were filled with bitterness and complaints about Camille’s ingratitude.

Camille Claudel died on 19 October 1943, and it was not until eight years later that her first retrospective was shown at the Musée Rodin in Paris, thanks to Paul Claudel. In the last few decades, there has been a renewed interest in her work in the Far East and United States as well as in Europe. The movie Camille Claudel has also helped us to see how she and Rodin were so closely connected, artistically and physically.

While she may have owed much to Rodin’s mentoring, one wonders how Camille might have fared had she lived a century later, when female artists were accepted equally. It is difficult to say what her life might have been like had she received the recognition denied by governments because of her gender. We owe a debt of gratitude to critics and museum curators for seeing the value of her work and bringing it to the public for a short period in her life. They saw, as we can see now, her sensitivity to the human condition and her eye for life experiences, as though she reached into her soul with each human figure she created.

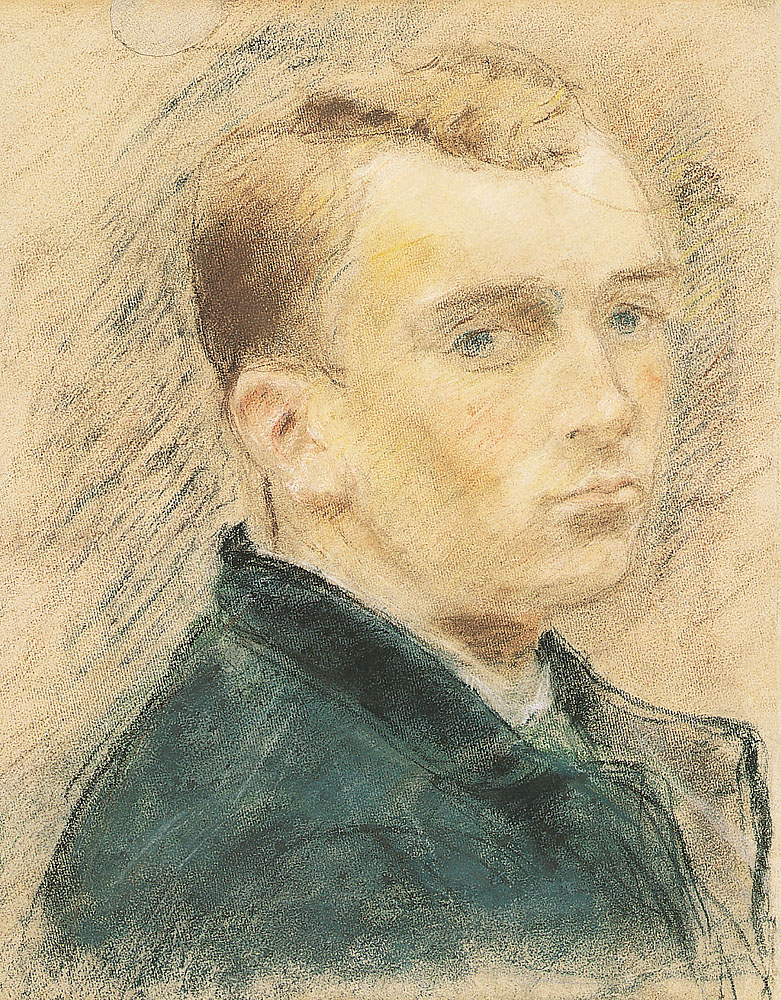

Paul Claudel at Thirty-Seven, 1905

Bronze, P. Converset casting (1910), 48 x 53 x 19 cm. Private collection