The prescient title of one of Claude Monet’s (1840-1926) paintings shown in 1874 in the first exhibition of the Impressionists, or as they called themselves then, the Société anonyme des artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs (the Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers), was Impressionism: Sunrise. Monet had gone painting in his childhood hometown of Le Havre to prepare for the event, eventually selecting his best Havre landscapes for display. Edmond Renoir, journalist and brother of Renoir the painter, compiled the catalogue. He criticised Monet for the uniform titles of his works, for the painter had not come up with anything more interesting than View of Le Havre. Among these Havre landscapes was a canvas painted in the early morning depicting a blue fog that seemed to transform the shapes of yachts into ghostly apparitions. The painting also depicted smaller boats gliding over the water in black silhouette, and above the horizon the flat, orange disk of the sun, its first rays casting an orange path across the sea. It was more like a rapid study than a painting, a spontaneous sketch done in oils – what better way to seize the fleeting moment when sea and sky coalesce before the blinding light of day? View of Le Havre was obviously an inappropriate title for this particular painting, as Le Havre was nowhere to be seen. “Write Impression,” Monet told Edmond Renoir, and in that moment began the story of Impressionism.

On 25 April 1874, the art critic Louis Leroy (1812-1885) published a satirical piece in the journal Charivari, that described a visit to the exhibition by an official artist. As he moves from one painting to the next, the artist slowly goes insane. He mistakes the surface of a painting by Camille Pissarro, depicting a ploughed field, for shavings from an artist’s palette carelessly deposited onto a soiled canvas. When looking at the painting he is unable to tell top from bottom, or one side from the other. He is horrified by Monet’s landscape entitled Boulevard des Capucines. Indeed, in Leroy’s satire, it is Monet’s work that pushes the academician over the edge. Stopping in front of one of the Havre landscapes, he asks what Impression: sunrise depicts. “Impression, of course,” mutters the academician. “I said so myself, too, because I am so impressed, there must be some impression in here… and what freedom, what technical ease!” At which point he begins to dance a jig in front of the paintings, exclaiming: “Hey! Ho! I’m a walking impression, I’m an avenging palette knife.” Leroy called his article, “The Exhibition of the Impressionists.” With typical French finesse, he had adroitly coined a new word from the painting’s title, a word so fitting that it was destined to remain forever in the vocabulary of the history of art.

Responding to questions from a journalist in 1880, Monet said:

I’m the one who came up with the word, or who at least, through a painting that I had exhibited, provided some reporter from Le Figaro the opportunity to write that scathing article. It was a big hit, as you know.

A Creek in St Thomas (Virgin Islands), 1856

Oil on canvas, 24.5 x 32.2 cm. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The Marne at Chennevières, c. 1864-1865

Oil on canvas, 91.5 x 145.5 cm. Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

The House of Père Gallien, Pontoise, 1866

Oil on canvas, 40 x 55 cm. Ipswich Borough Council Museums and Galleries, Ipswich (Suffolk)

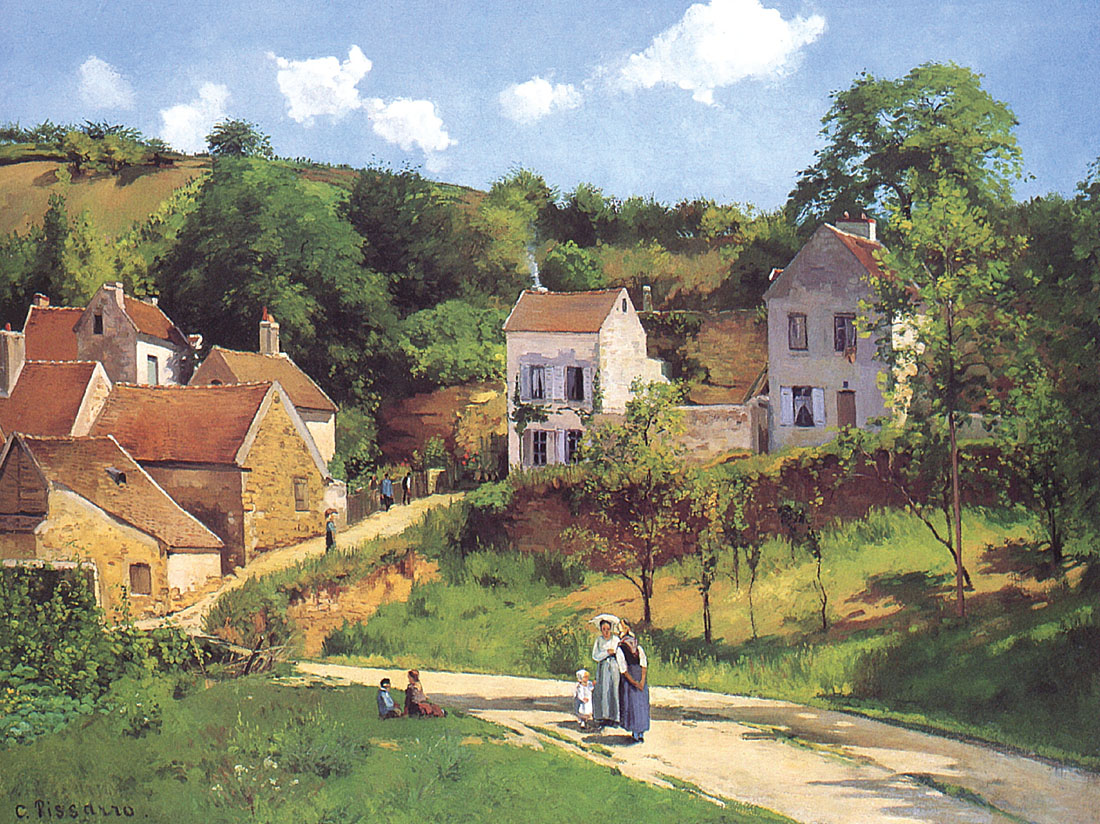

A Square in La Roche-Guyon, 1866-1867

Oil on canvas, 51 x 61 cm. Alte Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

The Impressionists and Academic Painting

The young men who would become the Impressionists formed a group in the early 1860s. Claude Monet, son of a Le Havre shopkeeper, Frédéric Bazille (1841-1870), son of a wealthy Montpellier family, Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), son of an English family living in France, and Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), son of a Parisian tailor, had all come to study painting in the independent studio of Charles Gleyre (1806-1874), whom in their view was the only teacher who truly personified Neoclassical painting.

Gleyre had just turned sixty when he met the future Impressionists. Born in Switzerland on the banks of Lake Léman, he had lived in France since childhood. After graduating from the École des Beaux-Arts, Gleyre spent six years in Italy. Success in the Paris Salon made him famous and he taught in the studio established by the celebrated Salon painter, Hippolyte Delaroche (1797-1856). Taking themes from the Bible and antique mythology, Gleyre painted large-scale canvases composed with classical clarity. The formal qualities of his female nudes can only be compared to the work of the great Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). In Gleyre’s independent studio, pupils received traditional training in Neoclassical painting, but were free from the official requirements of the École des Beaux-Arts.

Our best source of information regarding the future Impressionists’ studies with Gleyre is none other than Renoir himself, in conversation with his son, the renowned filmmaker Jean Renoir. The elder Renoir described his teacher as a “powerful Swiss, bearded and near-sighted” and remembered Gleyre’s Latin Quarter studio, on the left bank of the Seine, as “a big empty room packed with young men bent over their easels. Grey light spilled onto the model from a picture window facing north, according to the rules.” Gleyre’s students could hardly be less alike. Young men from wealthy families who were playing at being artists came to the studio wearing jackets and black velvet berets. Monet derisively called these students “the grocers”, on account of their narrow minds. The white house painter’s coat that Renoir worked in was the butt of their jokes. But Renoir and his new friends paid them no heed. “He was there to learn how to draw figures,” his son recalls. “As he covered his paper with strokes of charcoal, he was soon completely engrossed in the shape of a calf or the curve of a hand.” Renoir and his friends took art school seriously, to such an extent that Gleyre was disconcerted by the extraordinary facility with which Renoir worked. Renoir mimicked his teacher’s criticisms in a funny Swiss accent that the students used to make fun of him: “Cheune homme, fous êdes drès atroit, drès toué, mais on tirait que fous beignez bour fous amuser.” (Young man, you are very talented and very gifted, but people say that you paint just for fun). As Jean Renoir tells it: “Obviously,” my father replied, “if it wasn’t any fun, I wouldn’t paint!”

The Hermitage at Pontoise, c. 1867

Oil on canvas, 151.4 x 201 cm. Thannhauser Collection, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

The Conversation (The Road from Versailles to Louveciennes), 1870

Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm. Foundation E. G. Bührle Collection, Zurich

The Road to Versailles at Louveciennes, 1870

Oil on canvas, 50.5 x 58.4 cm. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown (Massachusetts)

Louveciennes with Mont Valérien in the Background, 1870

Oil on canvas, 45 x 53 cm. Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

All four artists burned with desire to grasp the principles of painting and neo-classical technique. After all, this was the reason that they had come to Gleyre’s studio.

They applied themselves to the study of the nude figure and successfully passed all their required exam competitions, receiving prizes for drawing, perspective, anatomy, and likeness. Each of the future Impressionists received Gleyre’s praise on some occasion.

One day Renoir decided to impress his teacher by painting a nude according to all the rules, as he put it: “tan flesh emerging from bitumen black as night, backlighting caressing the shoulder, and the tortured look that accompanies stomach cramps.” Gleyre was struck by Renoir’s impertinence, and his shock and indignation were not unwarranted: his student had proved that he was perfectly capable of painting as the teacher required, whereas all the other youths were bent on depicting their models “as they are in everyday life”. Monet remembers the way Gleyre reacted to one of his own nudes: “Not bad,” he exclaimed,

not bad at all, this business here. But it is too much about this particular model. You have a heavyset man. He has huge feet, which you depict as such. It’s all very ugly. So remember young man, when we draw a figure, we must always keep in mind the antique. Nature, my friend, is a very admirable aspect of research, but it provides no interest.

To the future Impressionists, nature was exactly what interested them the most. Renoir remembered what Frédéric Bazille had told him when they first met: “Large-scale classical compositions are over. The spectacle of everyday life is more fascinating.” All of them preferred living nature and bristled at Gleyre’s disdain for landscape. “Landscape to him was a decadent art,” recalls one of Gleyre’s students,

and the eminent status it had gained in contemporary art was an usurpation; he saw nothing in nature beyond frames and grounds, and in truth, he never made use of nature except as an accessory, although his landscapes were always treated with as much care and consideration as the figures he was called upon to include.”

Nevertheless, students in Gleyre’s studio would be hard pressed to find any constraints to complain about. It is true that the programme included the study of antique sculpture and the paintings of Raphael and Ingres at the Louvre. But in reality the students enjoyed complete freedom. They were acquiring indispensable knowledge of the technique and craft of painting, mastery of classical composition, precision in drawing, and beautiful paint handling. Although later critics often rightly noted their lack of such achievements. Monet, Bazille, Renoir and Sisley abruptly left their teacher in 1863. Rumour had it that the studio was closing due to lack of funds and to Gleyre’s illness. In the spring of 1863, Bazille wrote to his father: “Mr Gleyre is rather ill. Apparently the poor man’s life is at stake. All his students are devastated, as he is so loved by those around him.”

Chestnut Trees in Louveciennes, Spring, 1870

Oil on canvas, 59.5 x 73 cm. Museum Langmatt, Baden (Switzerland)

Outskirts of Louveciennes, the Road, 1871

Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 55.5 cm. Museum Sammlung Rosengart, Lucerne

The Fence, 1872

Oil on canvas, 37.8 x 45.7 cm. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

La Ruelle des Poulies, Pontoise, c. 1872

Oil on canvas, 52.4 x 81.6 cm. Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis

Many years later, the elder Renoir spoke enthusiastically about this period to his son. “The intransigents wanted to put their immediate impressions on canvas, without any translation,” writes Jean Renoir.

“Official painting, imitating imitations of the masters, was dead. Renoir and his companions were bon vivants… Meetings of the intransigents were impassioned. They longed to share their discovery of the truth with the public. Ideas came from all sides and intermingled; opinions came thick and fast. One of them seriously suggested burning down the Louvre.”

Sisley apparently was the first to take his friends landscape painting in Fontainebleau forest. Now, instead of a model skilfully placed upon a pedestal, they had nature before them and the infinite variations of the shimmering foliage of trees, constantly changing colour in the sunlight. “Our discovery of nature opened our eyes,” said Renoir. No doubt an equally important influence on their passion for nature was the public exhibition that same year (1863) of Édouard Manet’s (1832-1883) painting Luncheon on the Grass. The painting astonished the future Impressionists, as well as critics and observers. Manet had begun to accomplish what they dreamed of: he had taken the first steps away from neo-classical painting and moved closer to modern life. Truth be told, “burning down the Louvre”, was little more than a spontaneous expression bandied about in the heat of discussion, not a conviction. When asked if he had got anything out of Gleyre’s neo-classical studio, the elder Renoir replied to his son:

A lot, in spite of the teachers. Having to copy the same écorché (anatomical study) ten times is excellent. It’s boring, and if you weren’t paying for it, you wouldn’t be doing it. But to really learn, nothing beats the Louvre.

Gleyre’s illness was not the only reason the formal training of the Impressionists came to an end. In all likelihood they felt that they had learned everything their teacher was capable of teaching them during the time they had already spent in the studio. They were young and full of enthusiasm. Ideas about a new modern art made them want to get out of the studio as soon as possible to immerse themselves in real life and its vitality.

On their way home from Gleyre’s studio, Bazille, Monet, Sisley and Renoir stopped at the Closerie des Lilas, a café on the corner of boulevard Montparnasse and avenue de l’Observatoire, where they had long discussions about the future direction of painting. Bazille brought along his new friend, Camille Pissarro, who was a few years older than the others. The members of this small group called themselves the “intransigents”, and together they dreamed of a new Renaissance.

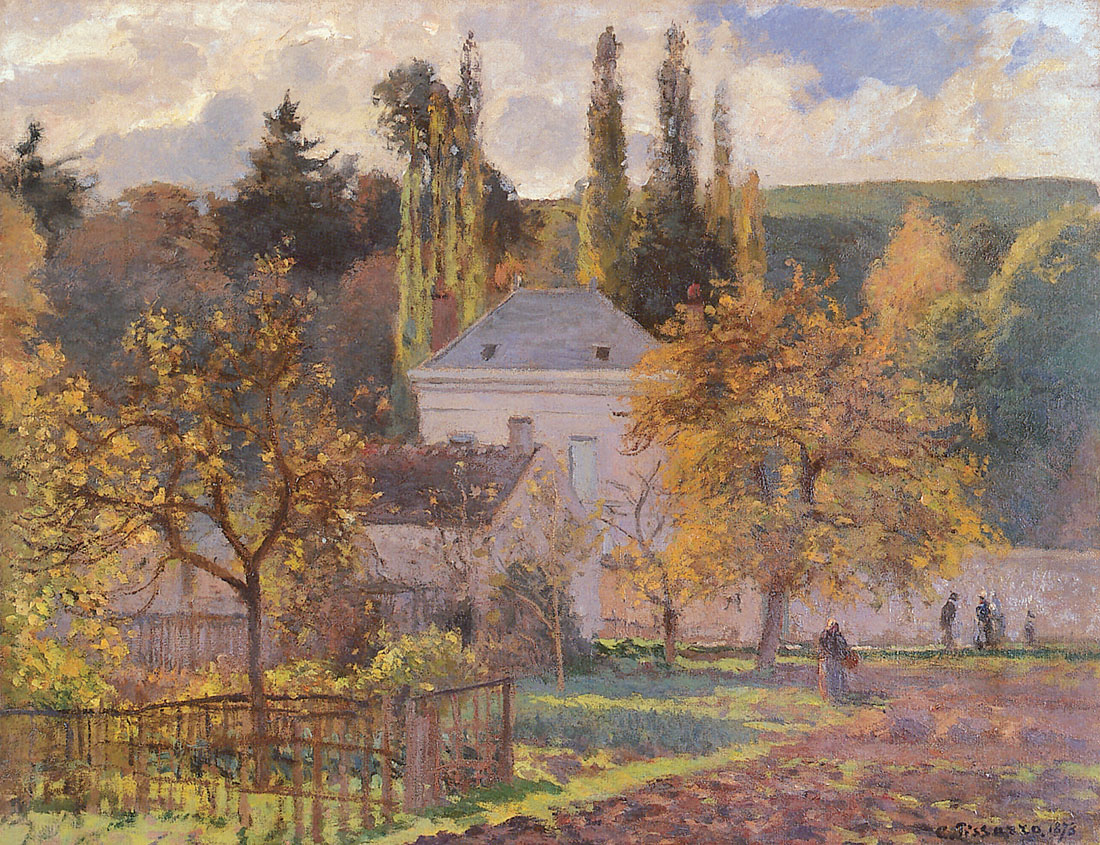

Bourgeois House in L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1873

Oil on canvas, 50.5 x 65.5 cm. Kuntstmuseum St. Gallen, St. Gallen

The River Oise near Pontoise, 1873

Oil on canvas, 46 x 55.7 cm. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown (Massachusetts)

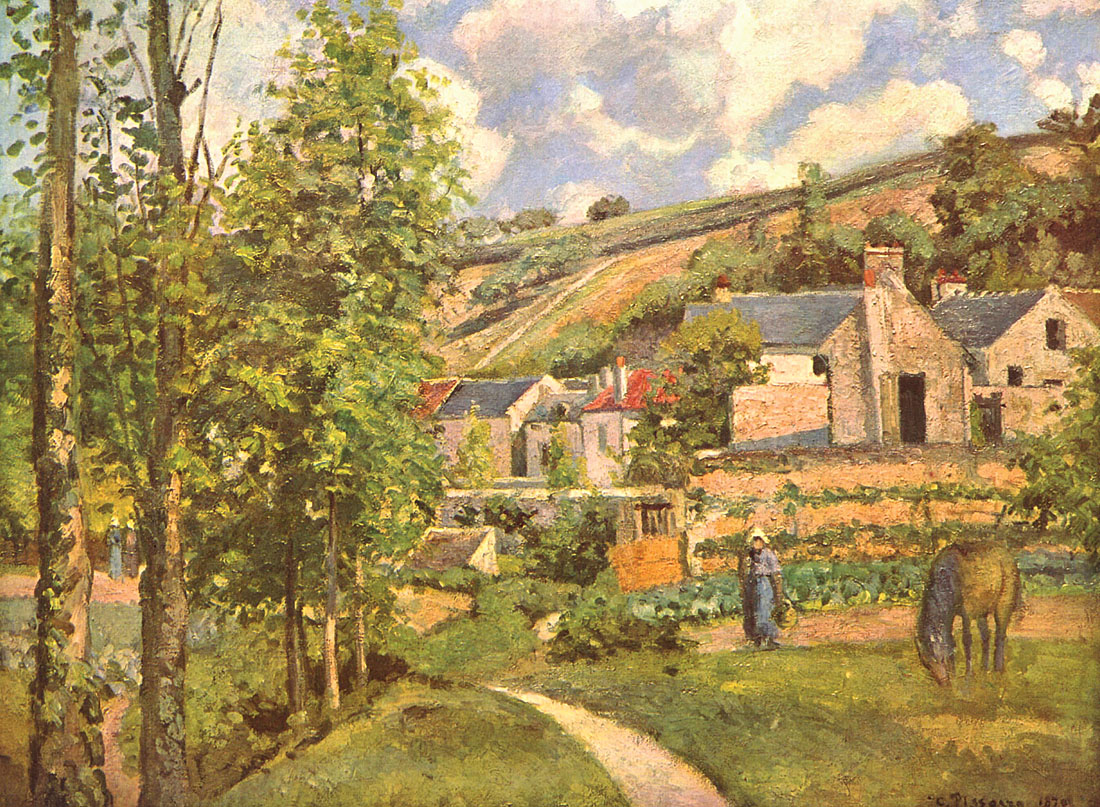

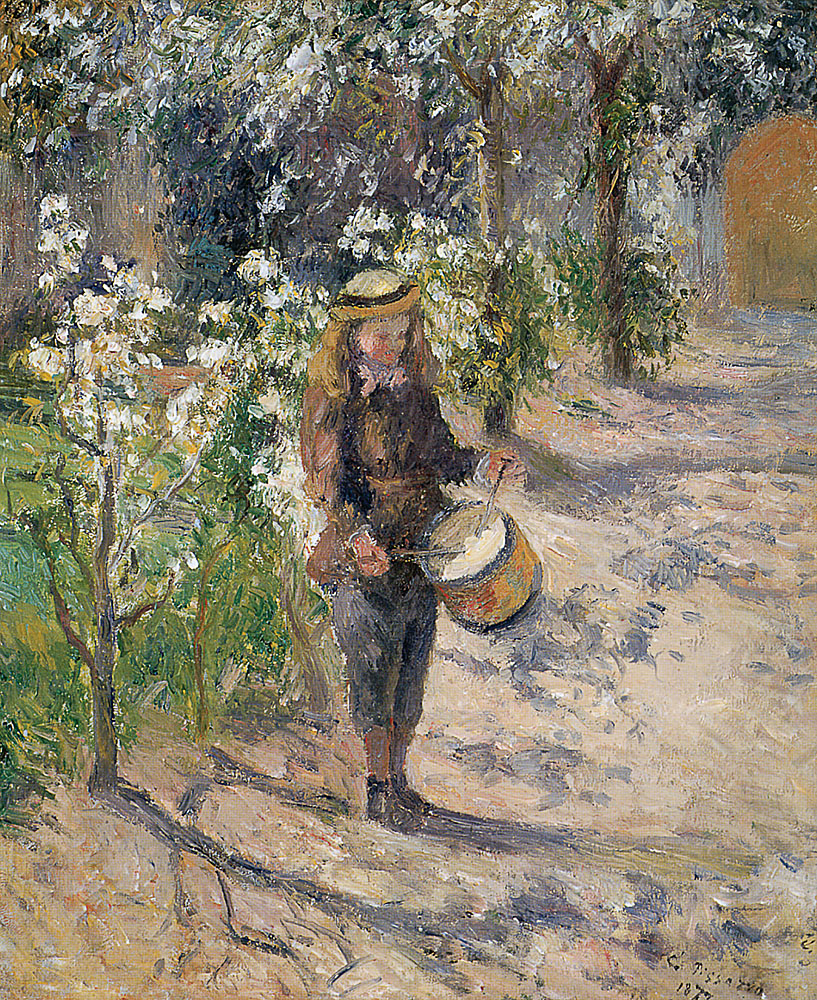

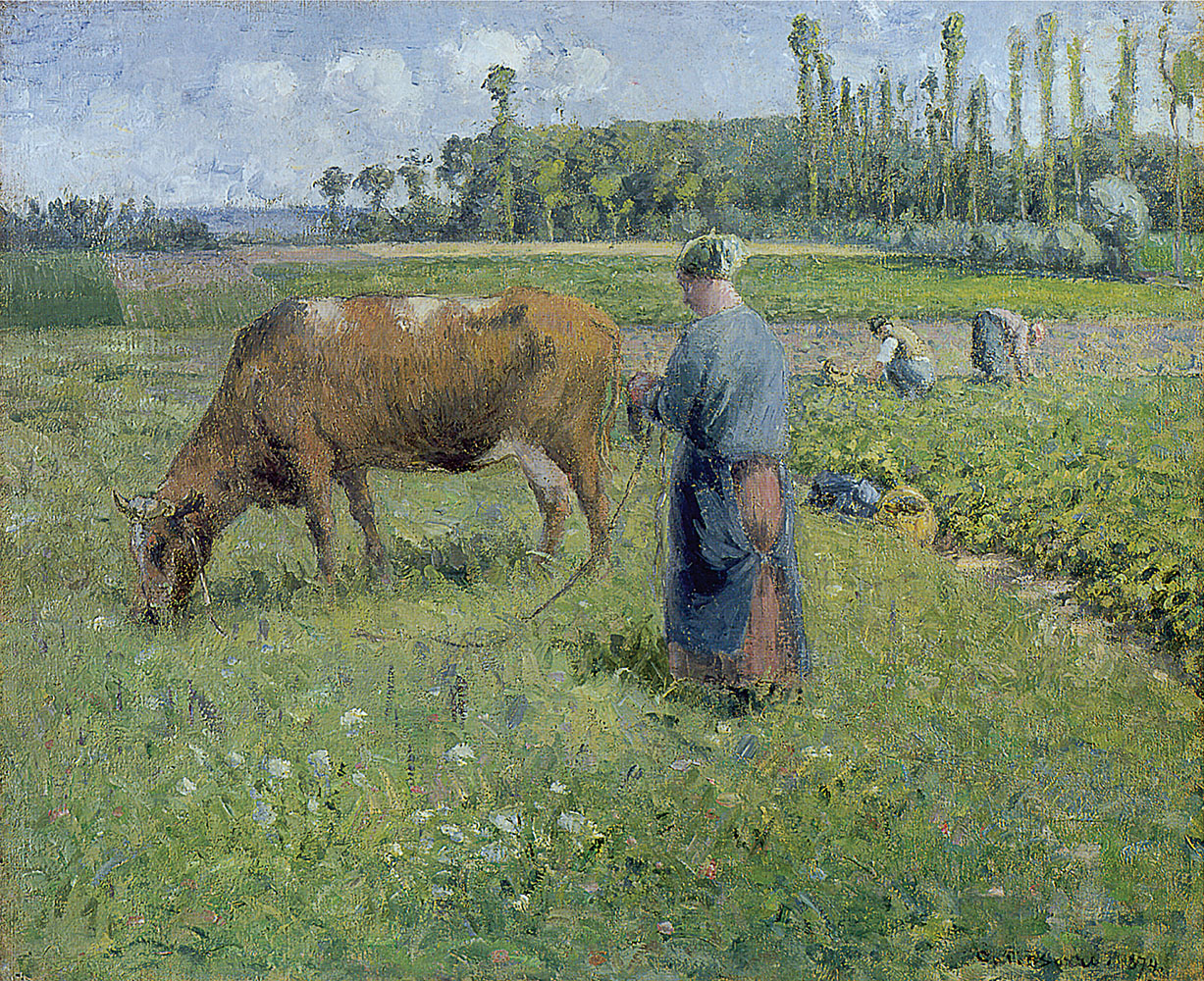

Peasant Pushing a Wheel-Barrow, Maison Rondest, Pontoise (Landscape from Pontoise), 1874

Oil on canvas, 65 x 51 cm. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

The Artist

At the request of Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922), Pissarro summarised his own biography in the following way:

Born at St Thomas (Danish Antilles) on 10 July 1830. Came to Paris in 1841 to enrol in the Savary boarding school in Passy. In 1847 I returned to St Thomas, where I began to draw while employed in a business firm. In 1852 I gave up business and left with Mr Fritz Melbye, a Danish painter, for Caracas (Venezuela), where I lived until 1855. I returned to St Thomas to work in business. I finally returned to France at the end of 1855 in time to see the Paris Universal Exhibition. Since then I have settled in France, and as for the rest of my life as a painter, it is linked with the Impressionist group.

This “rest” of the painter’s biography consists of his entire life, which was inseparable from Impressionism. Without this, the story of Pissarro’s life would have simply been a commonplace one, typical of all painters, or nearly so.

Camille Pissarro’s life began in an exotic world, on the rocky island of St Thomas not far from Puerto Rico. His father, “Pissarro the Jew,” owned a general store and wished to see his children carry on the business. He sent his son to France to study at a respectable secondary school in Passy, where Camille stayed for six years. This is where he began to draw and the principal of the school encouraged its students’ artistic inclinations. When he returned to the island Camille quietly busied himself at the hardware store for five years, but continued to draw. One day, while he was supervising merchandise being loaded at the port and sketching the sailors as they worked, he drew the attention of the painter Fritz Melbye (1826-1869), who was travelling through St Thomas. He persuaded Camille that he, too, could become a painter. Afterwards, Pissarro recalled he would not have been able to tolerate the quiet life at home for long, though he was well paid as an employee. He said he had wanted to break with his bourgeois life as soon as he could. This is why he abandoned everything, with little reflection, and ran away to Caracas with Melbye. He had to overcome a number of difficulties, and managed to do so thanks to youthful energy and enthusiasm. Still, the painter concluded that if he had had the chance to start all over again he would have followed the same path. On his return from Caracas Pissarro resumed his former job, but now his father was no longer opposed to his vocation. Camille drew continually, depicting everything he saw around him. He was fully aware that he would become a professional, and for this reason did an incalculable number of sketches and studies. At the time landscapes were already the centre of his attention, and he strove to learn how to render spatial depth and lay out the composition of a painting. Seeing how serious his intentions were, his father sent Pissarro to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts.

It is not accidental that Pissarro mentions the 1855 Universal Exhibition in his biographical sketch. It set out the different directions possible for him. There were works by Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and landscapes by Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), Johan Berthold Jongkind (1819-1891), and Jean-François Millet (1814-1875). It was impossible to overlook Gustave Courbet’s (1819-1877) “Realist Pavillion.” But the attention of the young painter from Saint Thomas was particularly drawn to Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s (1796-1875) painting. He even decided to go and see Corot, and ask his permission to become his student. Corot didn’t accept students, but he agreed to give Pissarro advice. Monet later remembered that in his youth Pissarro worked in Corot’s style. Since the model was excellent Monet didn’t disapprove of his friend and, on the contrary, followed his example. Nevertheless, when the Salon accepted Pissarro’s painting in 1859, its author appeared in the catalogue as a student of Antoine Melbye’s.

The Pond at Montfoucault, 1875

Oil on canvas, 73.6 x 92.7 cm. The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham

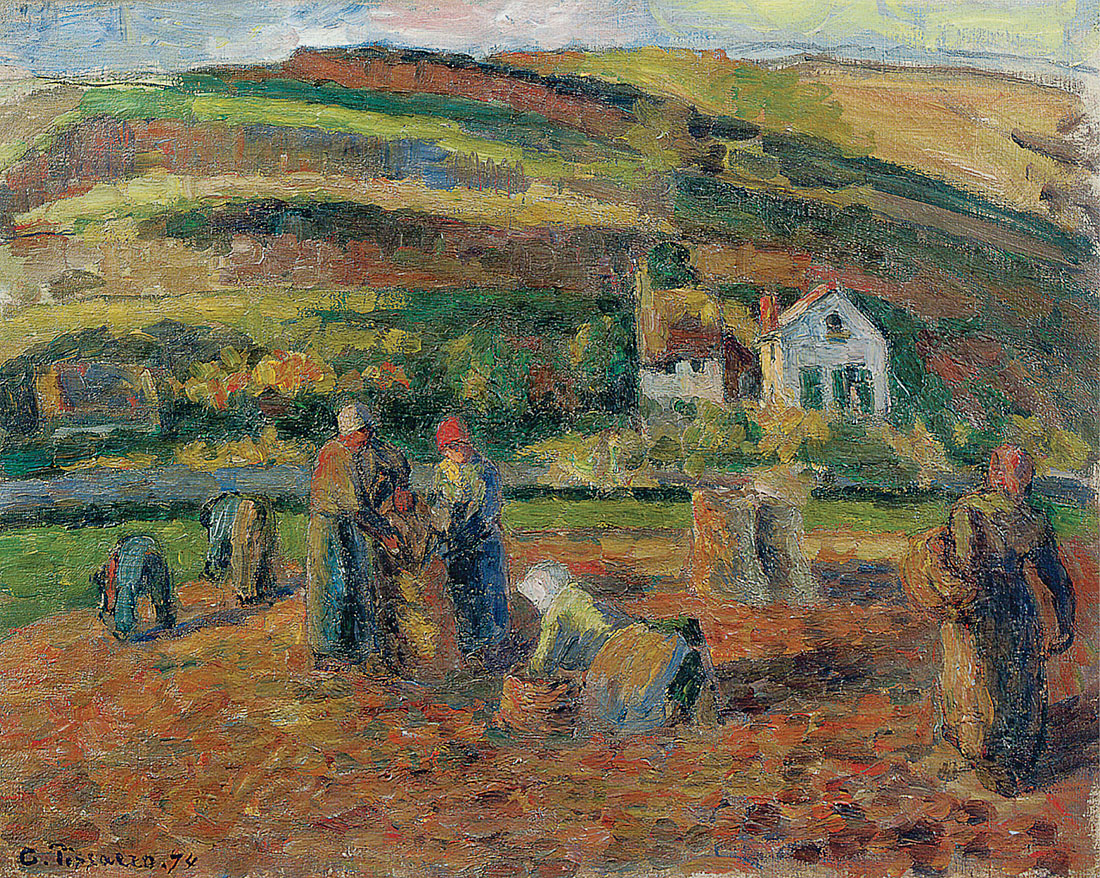

The Sower and the Ploughman, Montfoucault, 1875

Oil on canvas, 46 x 56 cm. Jorge Eljuri Antón Collection

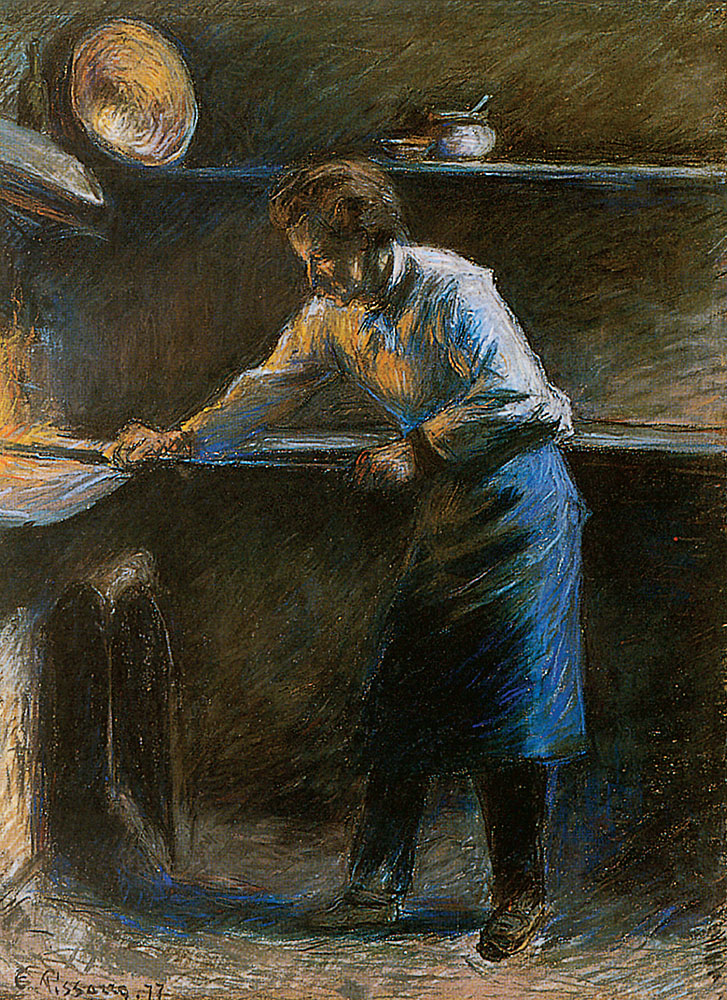

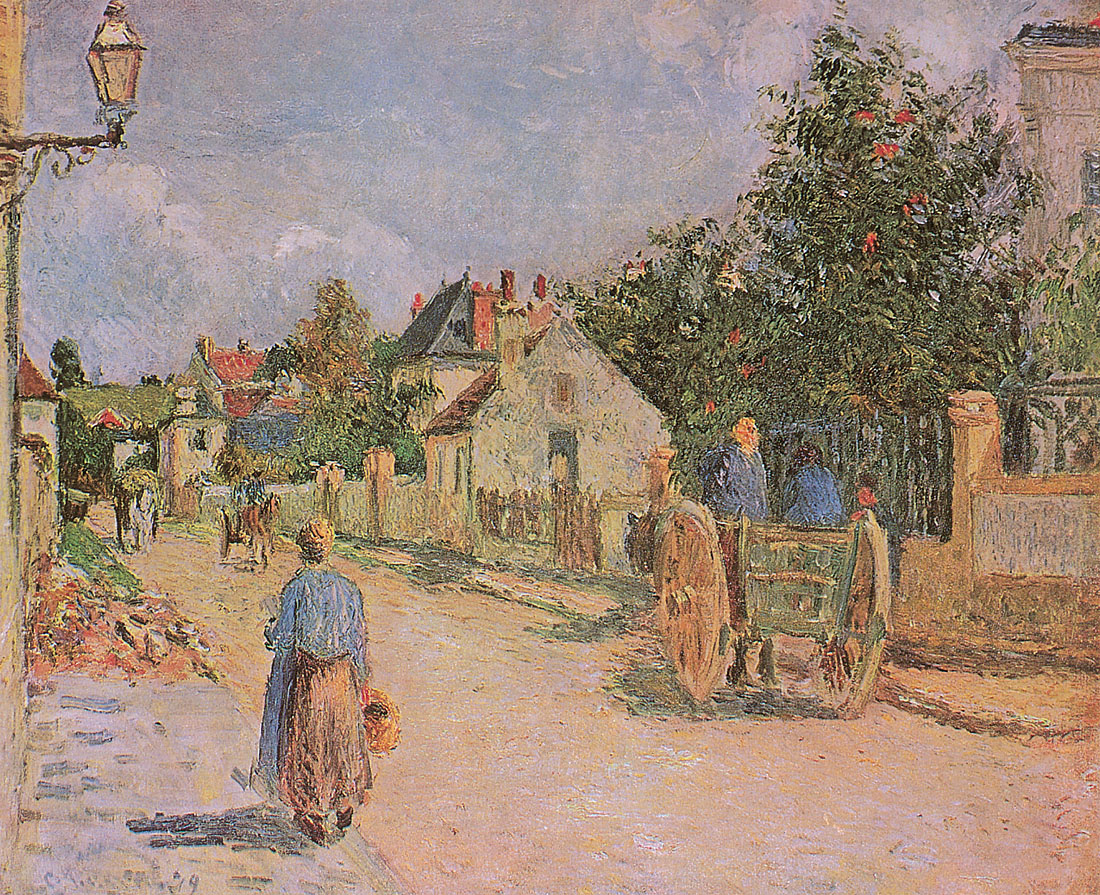

The Diligence on the Road from Ennery to l’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1877

Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 55 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Elder brother of Fritz Melbye, Antoine, was, at the time, known principally as a painter of seascapes. He had gone to a good school in Düsseldorf, mastered history and genre painting, and sold his works in various countries with success. His connection with Melbye played no insignificant part in Pissarro’s professional pictorial training. Later, in 1864, Pissarro signed his paintings “Student of Melbye and Corot.” The advice of both these masters greatly helped him in his future as a painter.

In 1859 Pissarro’s parents moved to Paris as well. His mother’s personal maid was a young peasant from Burgundy, Julie Vellay. Camille fell in love with her, but his father refused to recognise their union and withdrew his son’s monthly allowance. This was the start of the financial difficulties that were to continue to the end of Pissarro’s life. Camille and Julie were married in 1871, in England, and she remained a loyal companion throughout the painter’s difficult life. After he moved to Paris, Pissarro apparently tried to study at different studios connected to the École des Beaux-Arts, but soon became disappointed, and preferred to attend the Académie Suisse. What attracted the young people there was the freedom.

For a modest sum Pissarro could draw from the live model, without being worried about a teacher’s demands. It was at the Académie Suisse that he met Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). Pissarro never took lessons at Gleyre’s. Bazille, who had met him one day at Édouard Manet’s, brought him to the Closerie des Lilas, where they all liked to meet. He was six years older than the future Impressionists and two years older than Édouard Manet. His young friends soon nicknamed him “Père [Old Man] Pissarro”. He was impassioned, intelligent, and kind, and indeed became a sort of “father” to the Impressionists. As he appears in his Self-Portrait – in his painting smock, against a background of studies hanging on the wall – Pissarro is forty-three years old and, with his spreading beard and serious, direct gaze, he looked very much the patriarch. “Born in the Antilles, he expressed himself slowly, with a slightly lilting accent,” recounted Renoir to his son Jean. “He dressed sloppily, but chose his words with great care. He would become the theoretician of the new school”. Pissarro became a regular of the meetings at Café Guerbois, and was respected and liked by everyone there. The first of the critics to speak of Pissarro was Émile Zola (1840-1902), in 1866: “M. Pissarro is unknown, and doubtless no one will mention him,” he wrote:

Be informed that no one likes you here, that they feel your painting is too bare, too dark [...] An austere, solemn way of painting, an extreme concern for truth and justice, a fierce, intense will. You are enormously awkward, sir – you are an artist I like.

The landscape Banks of the Marne in Winter was accepted by the Salon in 1866. Pissarro had chosen a strange motif: a dark hill against the background of a cloudy, gloomy sky, an empty field, and an isolated farm. Zola, friend and defender of Édouard Manet, held a very favourable opinion of the artist and had brilliantly described his painting’s individuality.

That same year Pissarro moved to the small town of Pontoise. Daubigny had described to him the beauties of the countryside on the banks of the l’Oise River, and in addition his wife Julie Velay’s parents lived in Pontoise. In the end, he found places in the natural landscape there which corresponded with his own character. Later he would paint many remarkable canvases in the vicinity of Pontoise. But landscape painters are always prey to a degree of instability. Pissarro was no different, and felt the need to vary his locations, always searching for a landscape where he could fully express himself. In 1868 he settled down very close to Paris, in Louveciennes, where Sisley and Renoir’s relatives lived. His house was on the road from Versailles to Saint-Germain. He liked this region, as did the other future Impressionists, with the meandering course of the Seine, its islands, and the villages of Bougival, Marly, and Argenteuil. And like the others he worked enthusiastically in the open air, and his colour range gradually lost the dark, severe character Zola had noted, gradually becoming purer and lighter.

Madame Pissarro Sewing beside a Window, c. 1877

Oil on canvas, 54 x 45 cm. Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, Oxford

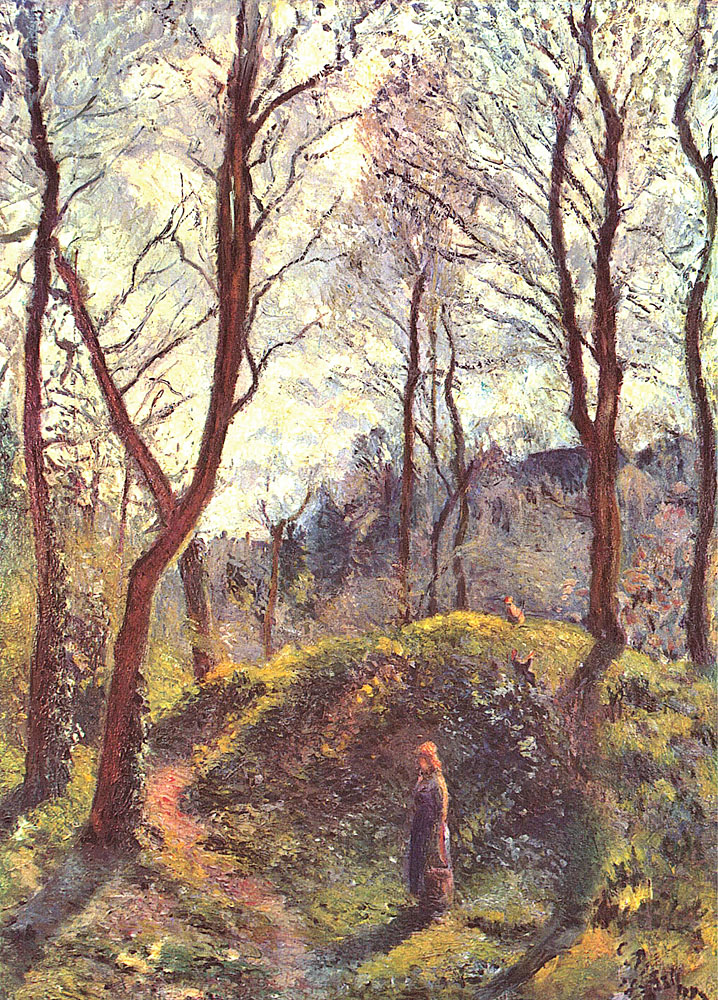

Edge of the Woods near L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879

Oil on canvas, 125 x 163 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

As a Danish national he was not drafted during the Franco-Prussian war, and when the Prussian army drew close to Louveciennes, Pissarro fled to Brittany with his family to his friend Piette’s farm. They left hurriedly, and he wasn’t able to take his paintings with him. The works at Louveciennes included not just his own, but canvases Monet had stored with him, as well. The Prussian soldiers who occupied Pissarro’s house destroyed almost 1500 of these paintings: they threw them over the muddy paths of the garden, soggy with rain, to make it easier for them to come and go. During this time Pissarro was in London, where his cousin lived and where his mother had gone, though it was not at all easy to leave them with Claude Monet and the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. But he had only one wish, to return to France. The critic Théodore Duret (1838-1927) told him in his letters of the looting of Paris during the Commune, and of the terror and despair that reigned in the city, saying he had only one dream, to escape to London as well. To this Pissarro replied:

I won’t stay here. It is only abroad that one can feel how fine, how great and hospitable France is. What a difference here! One is greeted only with contempt, indifference, and even coarseness: among colleagues there is the most selfish jealousy and mistrust [...] Except Durand-Ruel, who bought two small paintings from me. My painting isn’t getting anywhere, not at all, and this bothers me somewhat wherever I go [...] I may be back at Louveciennes before long. I lost everything there, there are only about forty paintings left out of 1500. What on earth did they do with all of them? [...] warriors!

On his return to France, Pissarro moved back to Pontoise, farther from Paris. The region was already populated with artists, and he had remarkable neighbours: Daumier’s house was just near Pontoise, in Valmondois, and Daubigny lived in the village of Auvers, frequently visited by his close friend Corot. Pissarro had boundless respect for all of them. Another remarkable person lived in Auvers, Dr Paul-Ferdinand Gachet (1828-1909), who treated painters, went to their favourite cafés, and bought their paintings.

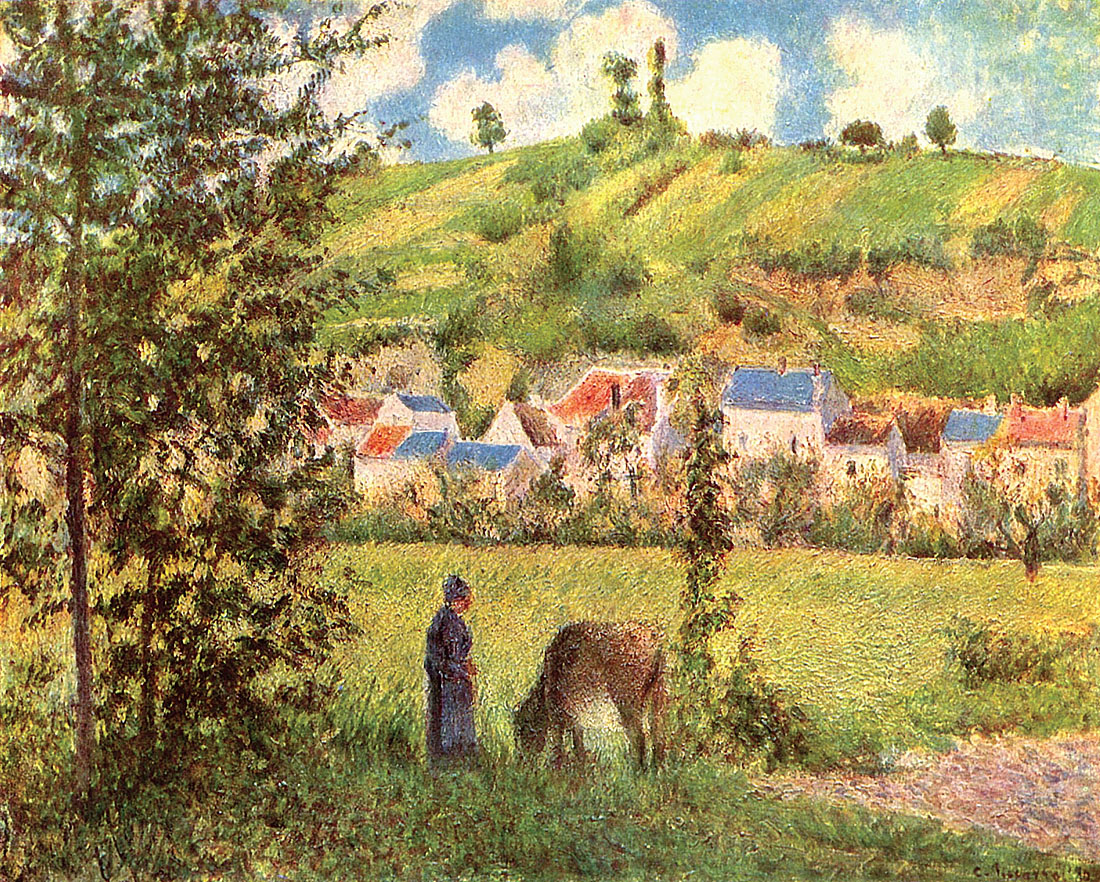

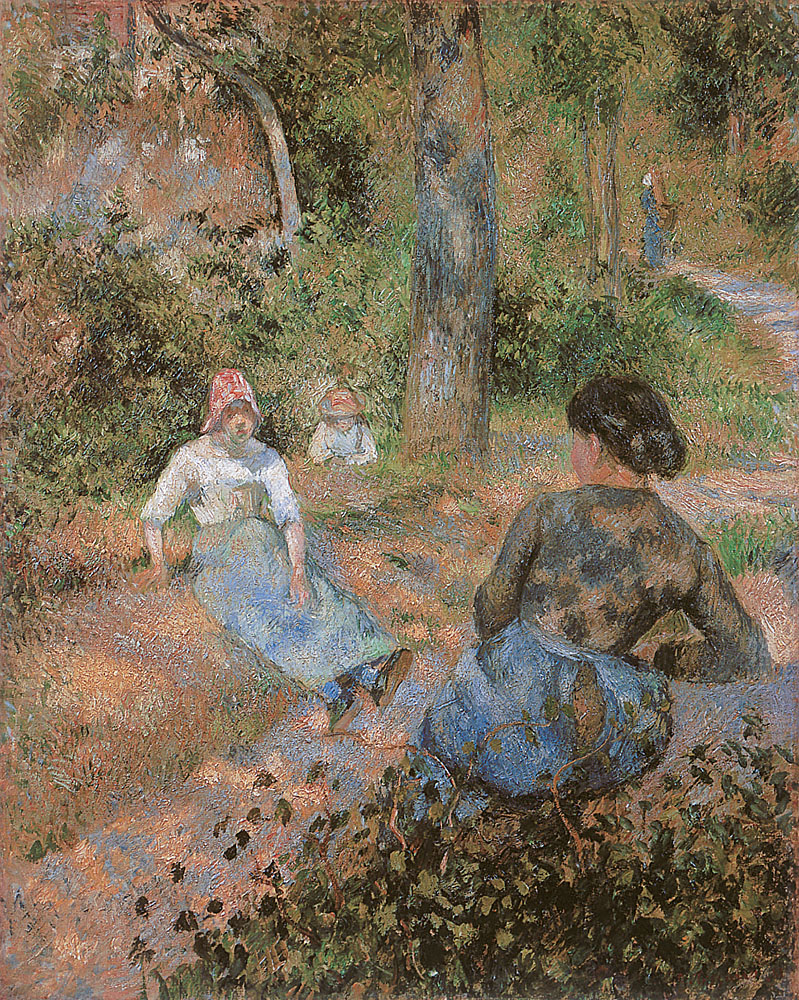

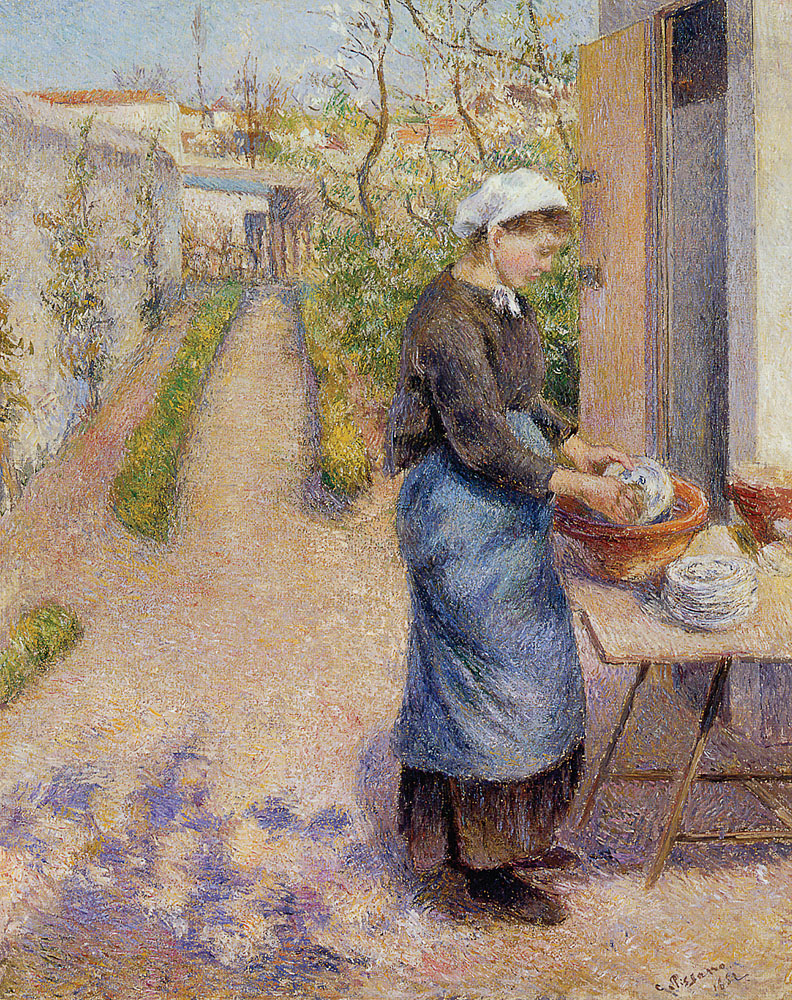

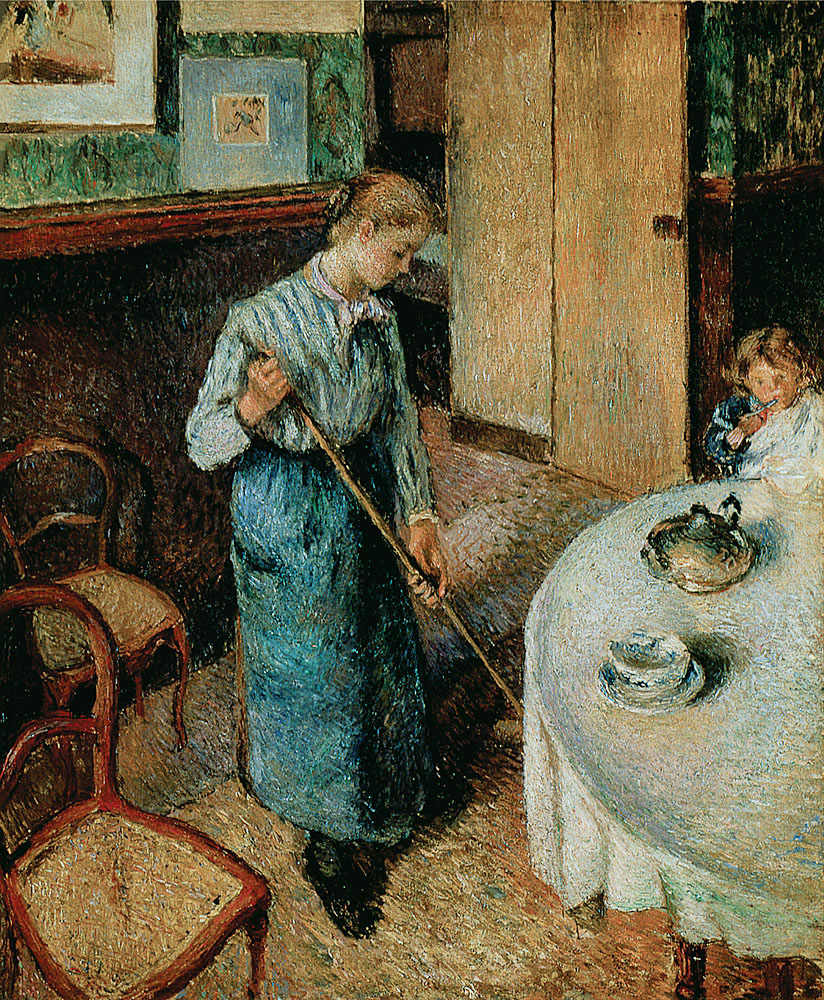

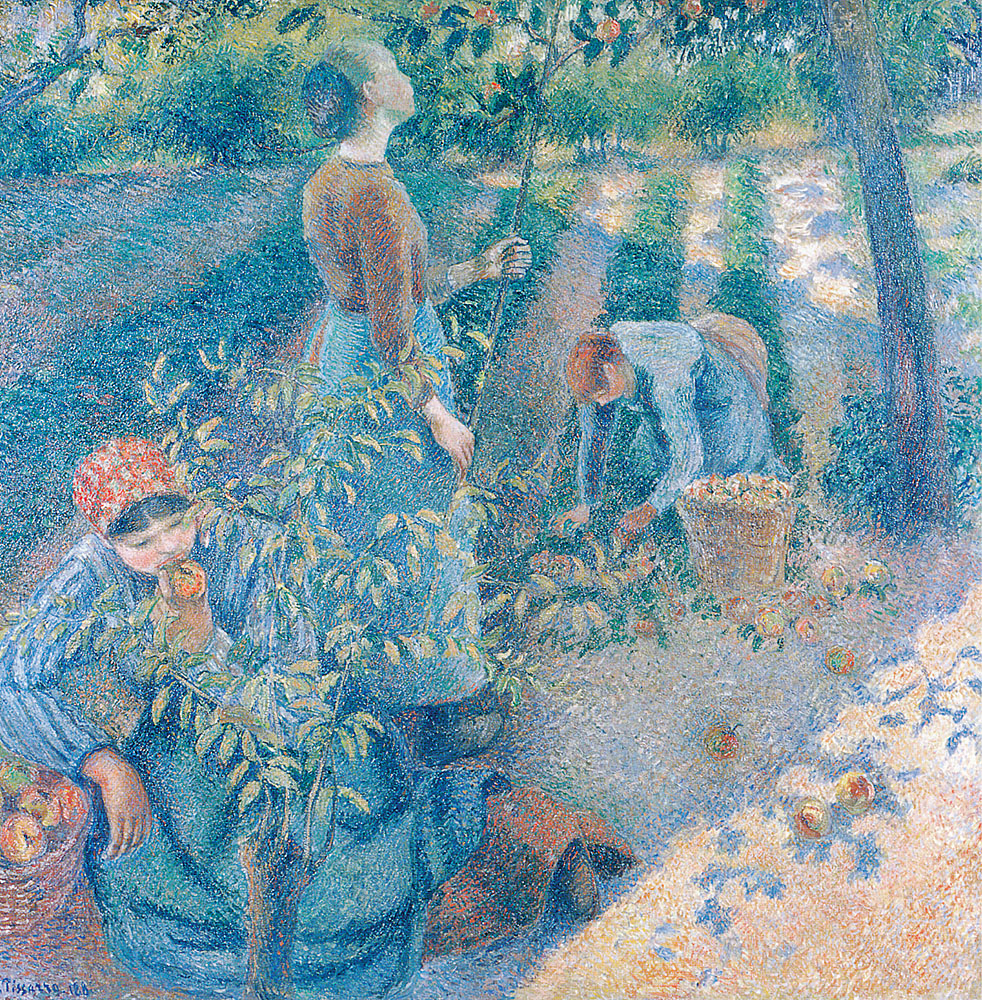

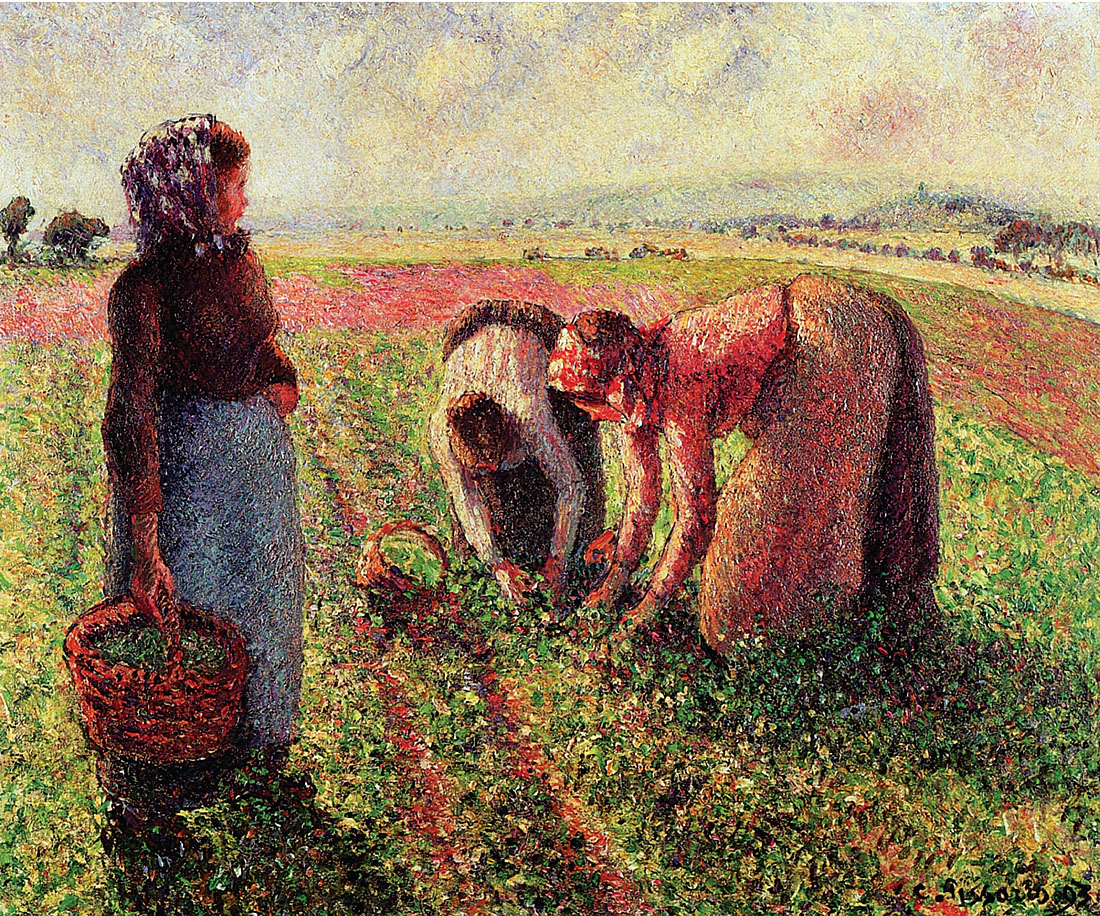

In addition, during the 1870s a man of thirty from the south of France arrived there, Paul Cézanne. He settled in Auvers and began to paint in open air together with Pissarro. One of Pissarro’s admirable qualities was his human warmth. He was ready to lend support to anyone in need of help. He was generous in his warmth towards Cézanne, who felt at home with Pissarro’s family and was in no hurry to leave Pontoise. When Pissarro was in Paris Cézanne and his oldest son Lucien wrote to him with news of the family in Pontoise. Pissarro taught Cézanne to lighten his palette, and only to paint with the three primary colours and their nearest derivative colours. Pissarro also had a teacher’s eye, and knew how to evaluate talent in others. He wrote to Duret from Pontoise, telling of Paul Cézanne’s “very strange studies, uniquely visualised”, and told him that this young painter from Provençe had surpassed all his expectations: his paintings were amazingly powerful and energetic. He said that if Cézanne stayed on at Auvers for some time longer, where he intended to settle, his work would astonish those painters who had so hastily criticised him. Later, Cézanne said Pissarro was like a father to him, and more – like a benevolent God. Beginning in 1879 another habitual guest of the Pissarro family’s was Paul Gaugin (1848-1903), then still only an amateur painter and collector. Gaugin also never forgot what knowing Pissarro had done for him and, a few months before his death, wrote in one of his letters: “He was one of my masters, and I would never repudiate him”. In the environs of Pontoise and Auvers Pissarro painted meadows and ploughed fields without end – simple, unpretentious motifs, most often in connection with peasants labouring. He himself said that he liked to represent nature “fully naked.” The year of the first Impressionist exhibition he was essentially painting in only a single tonality, his work was not yet completely free of Corot’s influence. Pissarro painted Ploughed Field, in pink-brown tones, to which he added only occasional green tones. His composition is inspired by Daubigny, who also painted his landscapes from a boat, in planes parallel to the horizontal edge of the canvas. This is how Pissarro also constructed the landscape, probably painted at the start of the 1870s, at Louveciennes – it was previously believed to have been done in the environs of Pontoise. Here the parallel planes reinforce the rhythm of the trees, which stand equidistant from each other and parallel to the lower edge of the canvas. The colour range is still rather dark. One thinks back to Zola saying that the public would not like this artist’s painting. And indeed this is not the poetry of rural landscape, or an idyllic nature far from urban civilisation. Pissarro paints people’s monotonous, day-to-day lives amidst a prosaic, familiar nature. In another landscape, The Wash House at Bougival, in addition to the women doing their washing, there is a still more prosaic detail: a little factory with a smoking chimney, rising out of the ground on this picturesque bank of the Seine.

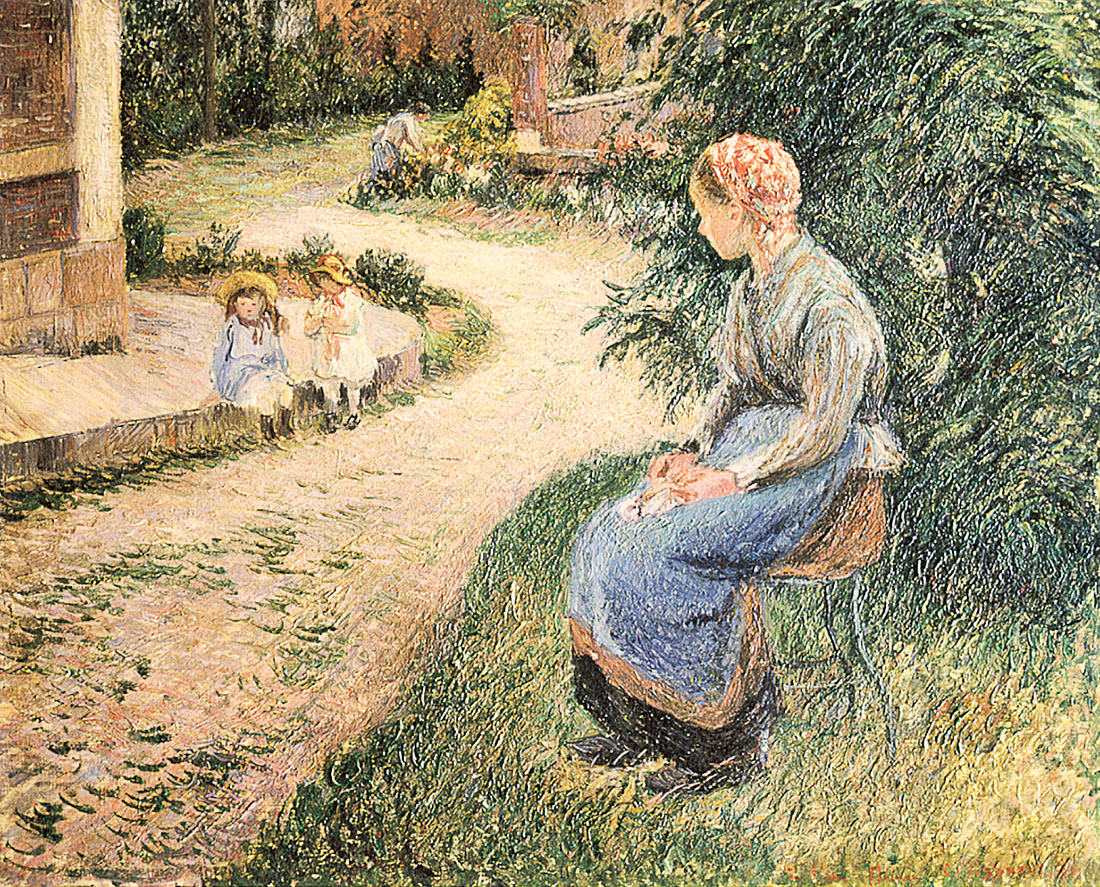

Young Peasant Woman Drinking her Coffee, 1881

Oil on canvas, 65.3 x 54.8 cm. Potter Palmer Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

In the Garden at Pontoise: A Young Woman Washing Dishes, 1882

Oil on canvas, 81.9 x 65.3 cm. The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, Cambridge

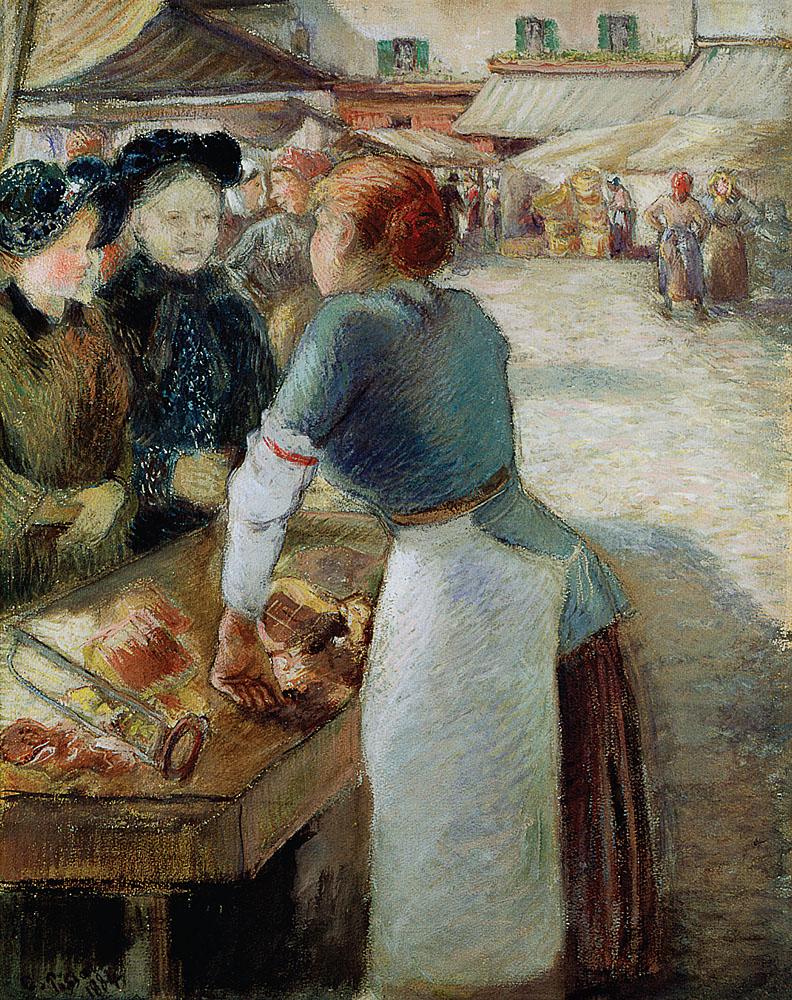

The Poultry Market at Pontoise, 1882

Oil on canvas, 81 x 65.1 cm, Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena

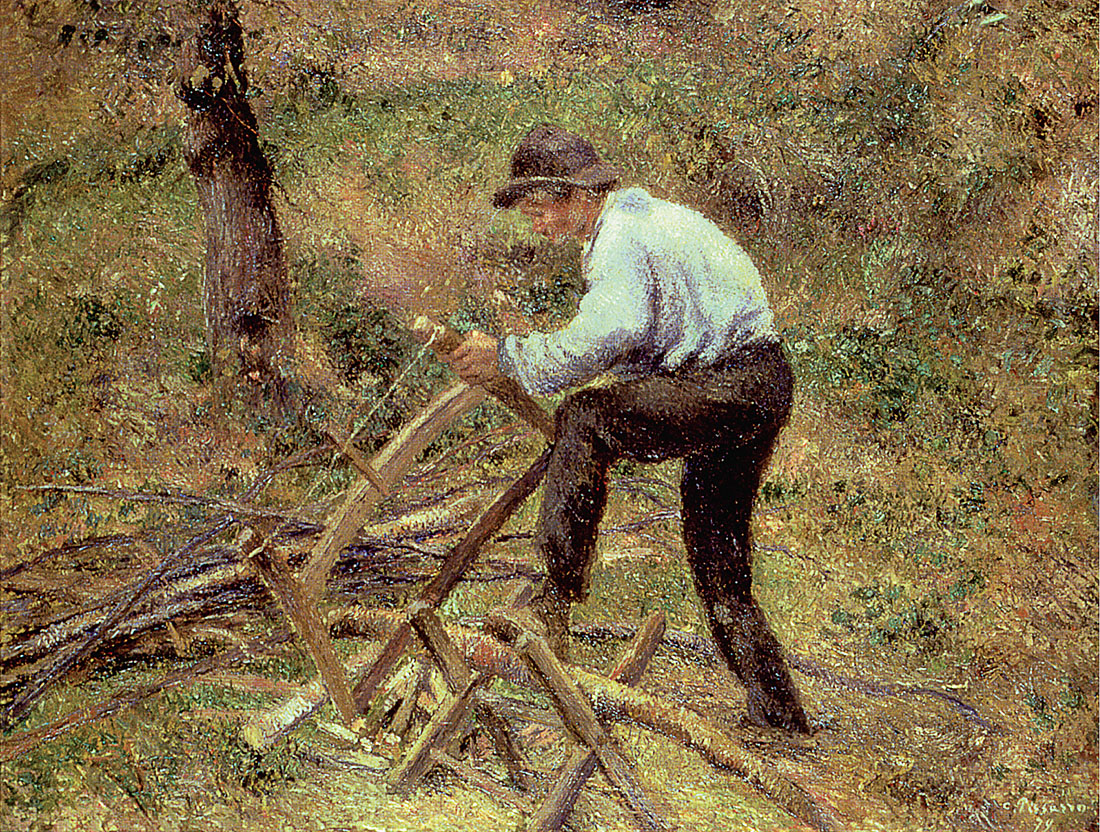

Even earlier, in 1869 or 1870, in Landscape in the Vicinity of Louveciennes, Autumn, Pissarro had painted backyards and kitchen gardens, instead of poetic paths and the reflection of the water. One of Pissarro’s best landscapes appeared at the first exhibition in Nadar’s (1820-1910) studio in 1874: Hoarfrost, in which the motif is completely devoid of any charm whatsoever. He painted a gentle, even slope, with little twisted trees and the figure of a peasant bending under the weight of a bundle of firewood. Still, it is here that Pissarro’s special poetry reveals itself. The golden colour range, which joins the earth and the sky, gives the impression of gentle sunlight and the whitish veil of the morning frost. For his landscape motif in this painting, before Monet and Sisley, Pissarro chose a scene in nature that was about to change the very next moment. The shadows of the poplars cross the horizontal planes of the landscape at a diagonal. The trees themselves are not included in the painting, they are external to the picture. This type of composition recalls Édouard Manet’s constructions in his paintings, where the viewer seems to be included within the space of the pictorial work. Afterwards, Pissarro would more and more frequently do canvases where the emphasis was on rendering atmospheric conditions; this was particularly so in his landscapes of snow.

Nevertheless, around the time of the first exhibition Pissarro had already found his own vision of nature, which made him distinct from his landscape-painter friends. In 1873, with remarkable insight, the critic Paul-Armand Silvestre (1837-1901) wrote: “At first glance one has trouble distinguishing M. Monet’s painting from M. Sisley’s, and the latter’s style from that of M. Pissarro.” This was, in fact, the impression of the critics. Even in 1877, when viewers had accustomed themselves to distinguishing the Impressionist painters, Philippe Burty wrote that they all had the same flaw:

Their landscapes, which upon scrutiny cannot be confused with one another, have one unpardonable flaw for us: they reduce trees to the state of incorporeal phantoms, and these trunks and branches, which have their beauty the same as the human body and its limbs, are left with the unreasonable stiffness of telegraph poles and shapeless twigs.

But Silvestre had already been aware of each one’s individuality before the first exhibition. For him Pissarro was “the most authentic and the most naïve” among them. In Pissarro’s painting, objects do not, as a rule, dissolve into the surrounding air and become shimmers of colour. On the contrary, in L’Hermitage Hillside, Pontoise, 1873, the houses built of rough stone have a palpable realism. In the landscape Climbing Path at L’Hermitage, 1875, the tiered cottages on the slope of the hill appear, with their sharp definition and geometric shapes, to prefigure the cubism of the future. In the famous The Red Roofs, 1877 the shadows on the tree trunks and the volumetric clarity of the red-roofed houses almost create a relief effect on the canvas.

Pissarro was convinced of the need for his group of friends to carve out an independent niche. Among the future Impressionists he was one of the most courageous. “You are right, my friend, we are beginning to have an impact,” he wrote to Théodore Duret in February 1873:

we are being strongly challenged by some of the established masters, but should these differences of opinion come as any surprise, when one arrives, uninvited, and plants one’s modest flag in the middle of the fracas? [...] We hope to forge ahead without concern for the opinions of others.

Poultry Market at Gisors, 1885

Gouache and black chalk on brown paper mounted on canvas 82.2 x 82.2 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Market at Gisors, 1887

Black ink, gouache, and watercolour with lead white on paper, 31 x 24 cm. Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus (Ohio)

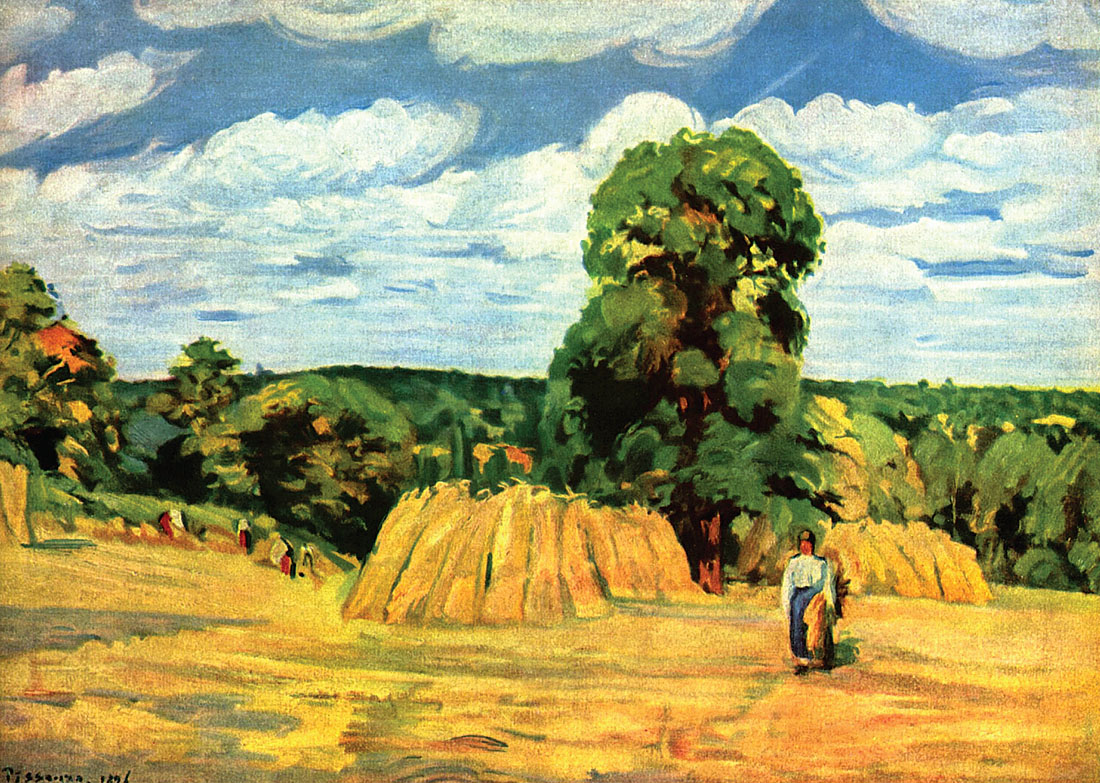

The Gleaners, 1889

Oil on canvas, 65.4 x 81.1 cm. Permanent loan of the Emile Dreyfus Foundation. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel

In 1874 Pissarro took an active part in organising their first exhibition. During discussions over its organisation he insisted on the need for creating a cooperative. As an example he proposed the bylaws of the bakers’ union, which he had learned of in Pontoise. He also proposed a system in which each of the painters would be well positioned when the time came to hang the paintings. To avoid conflicts Pissarro thought it necessary to determine by lot where each painting would be hung. But all these proposals were rejected: they seemed too radical to the other painters.

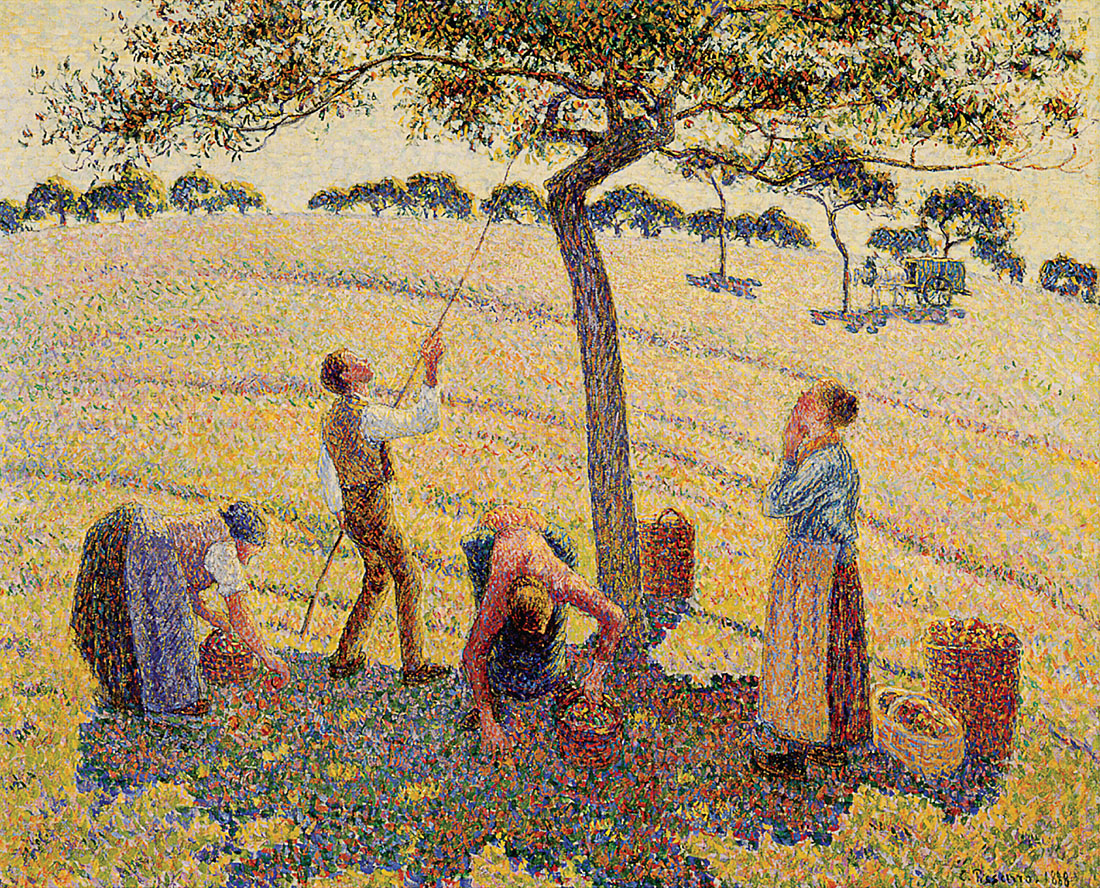

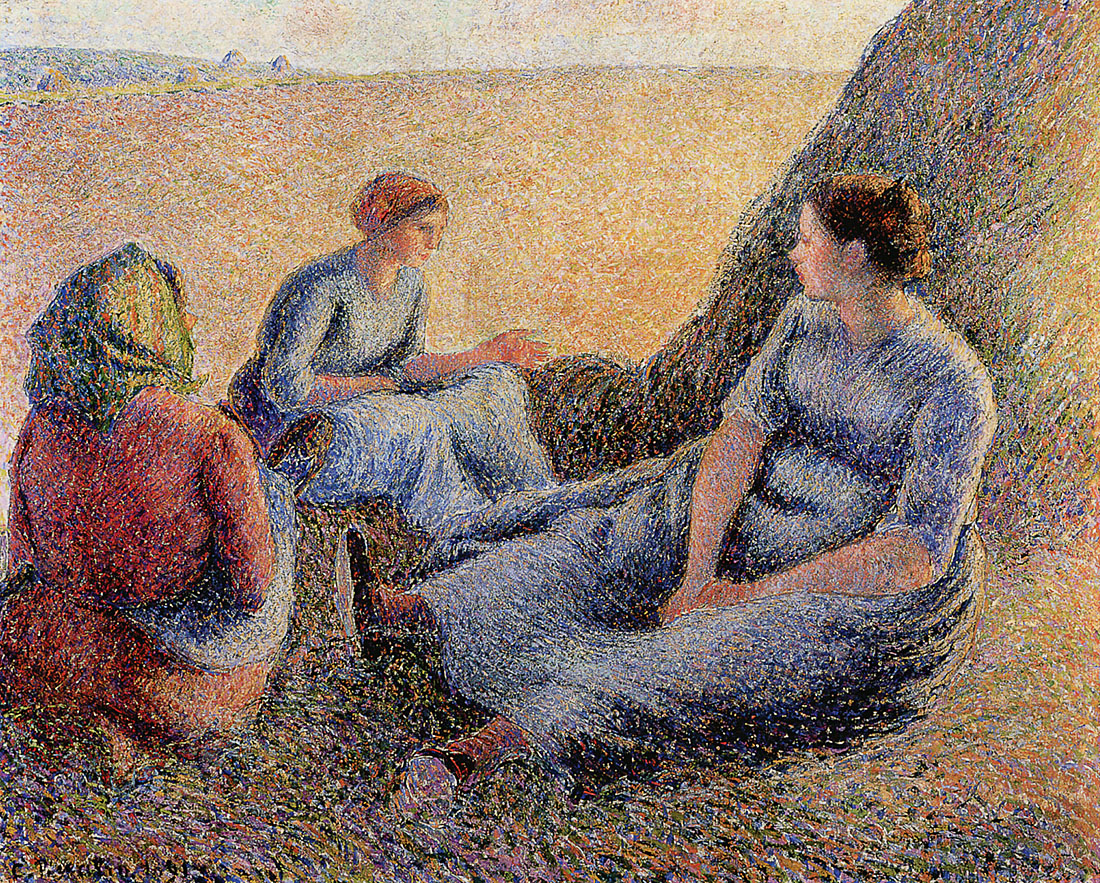

Pissarro’s ideas during the discussions about the exhibition emerged from his continuing interest in the social aspects of life. Pissarro remained poor in spite of relentless, determined work, and in his situation he felt himself the equal of the peasants he saw working hard in Pointoise and other villages nearby. This also goes far to explain why Pissarro was the only one among the group of Impressionists to inherit Millet’s rural motifs. Peasants appear in his landscapes at work and at rest. In 1873 the critic Théodore Duret, a great friend of Pissarro’s, wrote to the painter that he had bought his landscape with three donkeys and a little shepherdess. The critic said it made no difference to him how the work was painted, with a light or dark palette, because all that made no real difference: in terms of the intensity of feeling, this landscape was as wonderful as a painting by Millet. The comparison with Millet was no accident: Pissarro had at one point seriously intended to take up genre painting. In 1874 he wrote to Théodore Duret that he was going to leave the forest, where he had been staying an entire month, and return to Pontoise. He said he had already started to depict people and animals, and had done a few genre paintings. But he felt timid and uncomfortable in this style. Since his youth he had worked at nurturing the landscape painter within him, and had some success in this: it was also the genre to which all his friends were devoting themselves. For a certain time Pissarro was very interested in the social theories of the anarchists, but for him the truth to be found in art outweighed all others. Much later, in 1892, he wrote that he had read Bread and Freedom by the Russian anarchist Pjotr Alexejewitsch Kropotkin (1841-1921). While he understood that the idea was utopian, this did not make the dream any less wonderful. Since there had in fact been examples of utopias becoming realities, there was nothing to prevent one believing that someday this utopia would be achieved as well, provided humanity did not first collapse into utter barbarity. But Pissarro found Kropotkin’s thoughts on art unacceptable. Kropotkin believed one had to live the way peasants lived in order to understand them.

Pissarro said one had to have a passion for one’s subject. And for this, it did not help to become a peasant: first and foremost one had to be an artist. In all, Pissarro showed several dozen of his landscapes at every Impressionist exhibition until the eighth and last, in 1886. He was the only one to take part in all of their group exhibitions, and never again to submit his works to the Salon. He painted flowering fields and ploughed fields, the bare branches of trees in winter, apple trees blossoming impulsively, and light blue shadows and pink light on the snow. The Road to Ennery Near Pontoise, 1874, inevitably brings to mind Sylvestre’s reference to Pissarro’s “naïvete.” Amidst the gently sloping, seldom varying hills that he never tired of painting, little figures appear on the country paths: two travelers on horse carts, a peasant with a sack on his shoulders, and two women wearing hats. It is a world that is real and childlike at the same time, as in the works of naïve painters.

Peasant Women Planting Poles into the Ground, 1891

Oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm. Graves Gallery, Sheffield Museums, Sheffield

The Marketplace, Gisors, 1891

Gouache over traces of charcoal on fabric mounted to thin cardboard, 35.6 x 26 cm. Louis E. Stern Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

Pissarro dearly loved Paris, and visited when he could, but his poverty and his work with rural landscapes kept the family in the provinces. They had seven children, and later lost one of their daughters. Country life was far less expensive and the painter’s wife made things somewhat easier by growing vegetables and raising hens and rabbits. Despite his indigence, Pissarro remained the same with his friends. Life had done its best to break him, yet he continued to be the heart and soul of the clan, “Old Man Pissarro”, and he was always ready to offer help. When he received a “sad and kind” letter from Monet in Pontoise, lamenting the trouble he was having selling his paintings, Pissarro replied that, although “my patch of land is small and my cupboard is bare,” he would be happy to let Monet know if he learned of any good opportunities. In 1882 the Pissarro family moved to the small village of Osny, about five kilometres from Pontoise, where they could live even more simply.

The painter believed his financial situation was somewhat stable now. “I’m not being ‘showered with gold,’ as the romantics say,” he wrote to Duret. “I’m enjoying the fruits of modest, but consistent sales.” In September he even decided to make a journey through the Aube region and the Côte d’Or, hoping to find new motifs: “Old towers, churches, and old houses with a romantic air about them – these would be extremely interesting to our fine modern eye,” he wrote. In 1884 Pissarro again moved a bit farther north to Éragny on the Epte River, this same little river on whose banks sat Claude Monet’s Giverny. He settled into a very large but simple farmhouse right on the river bank, facing the village of Bazincourt. The meadows and gently sloping hills of Éragny served as Pissarro’s “studio”, as did the meadows of Giverny for Claude Monet. Like all the Impressionists Pissarro worked devotedly, in the rain as well as on days with frost, waiting long hours for the atmospheric phenomenon he needed. Catastrophic weather was often a source of delight for the painter. “I won’t have the chance to finish my two P [paintings],” he wrote to Durand-Ruel, “I’m not seeing the hoarfrost effects: on the other hand I’ve had some superb flooding, but it’s gone so fast!”

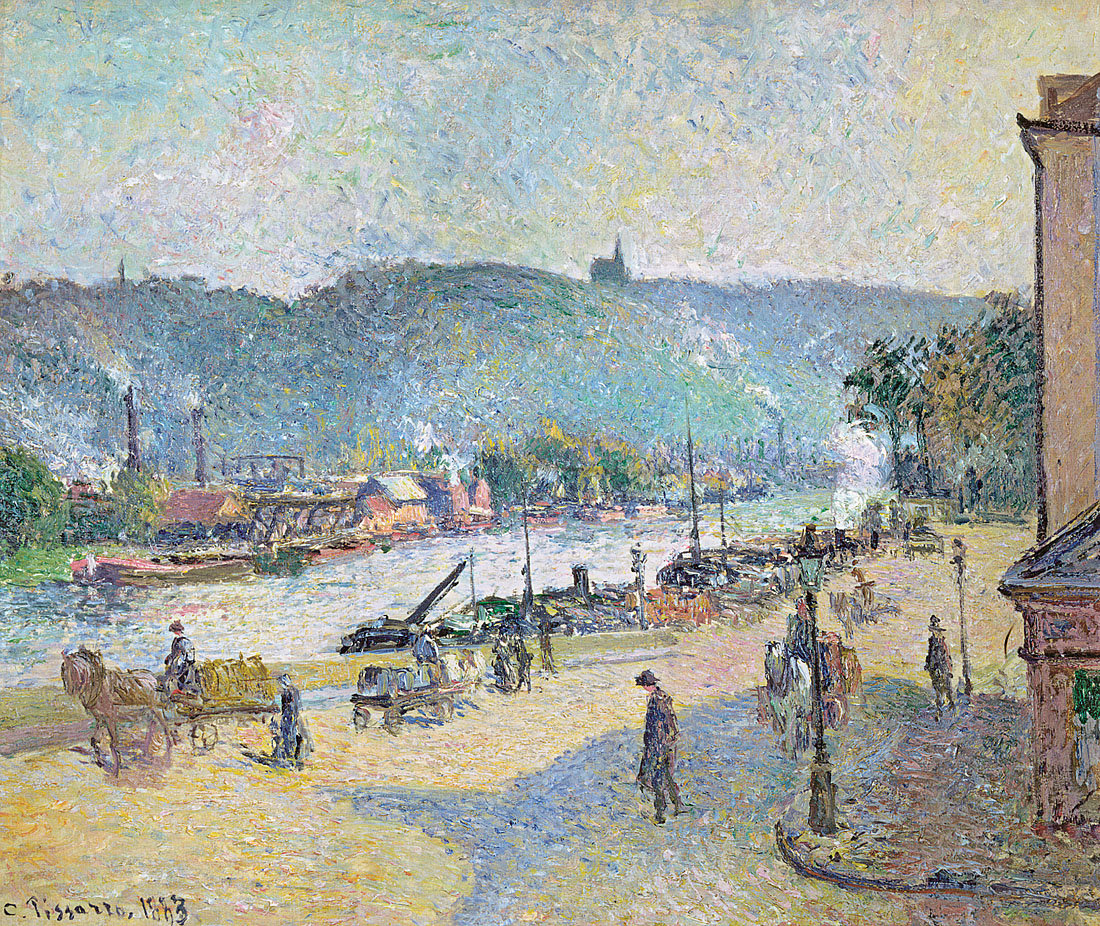

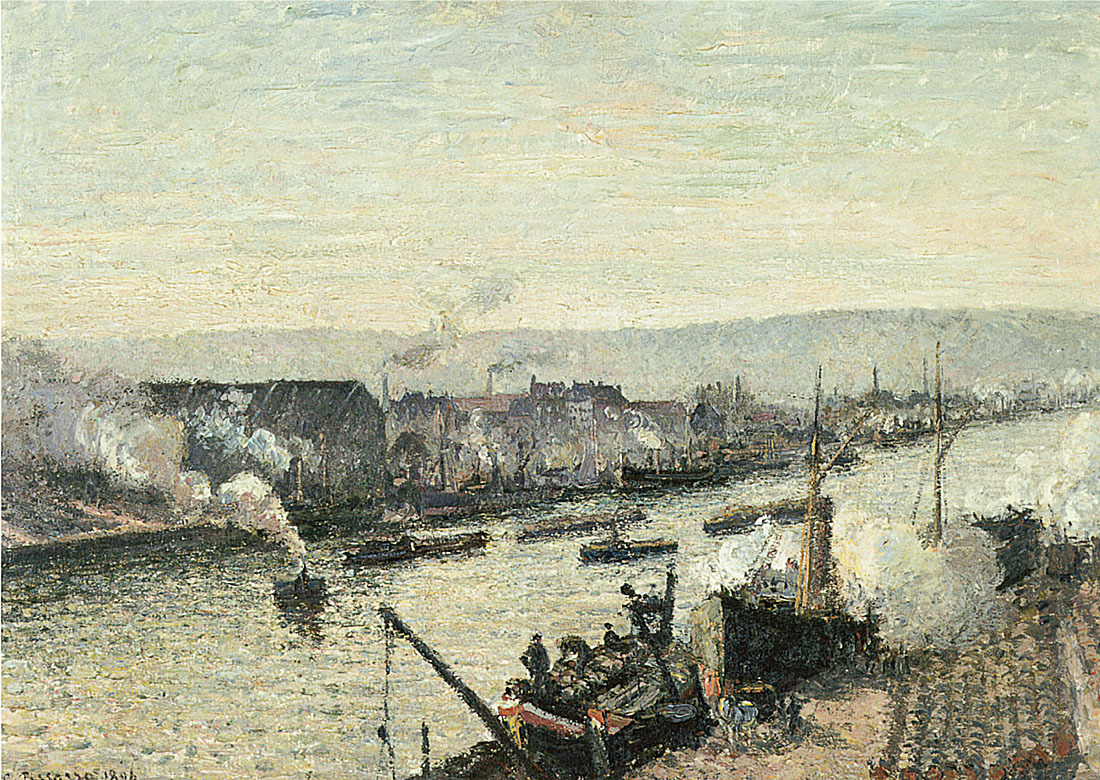

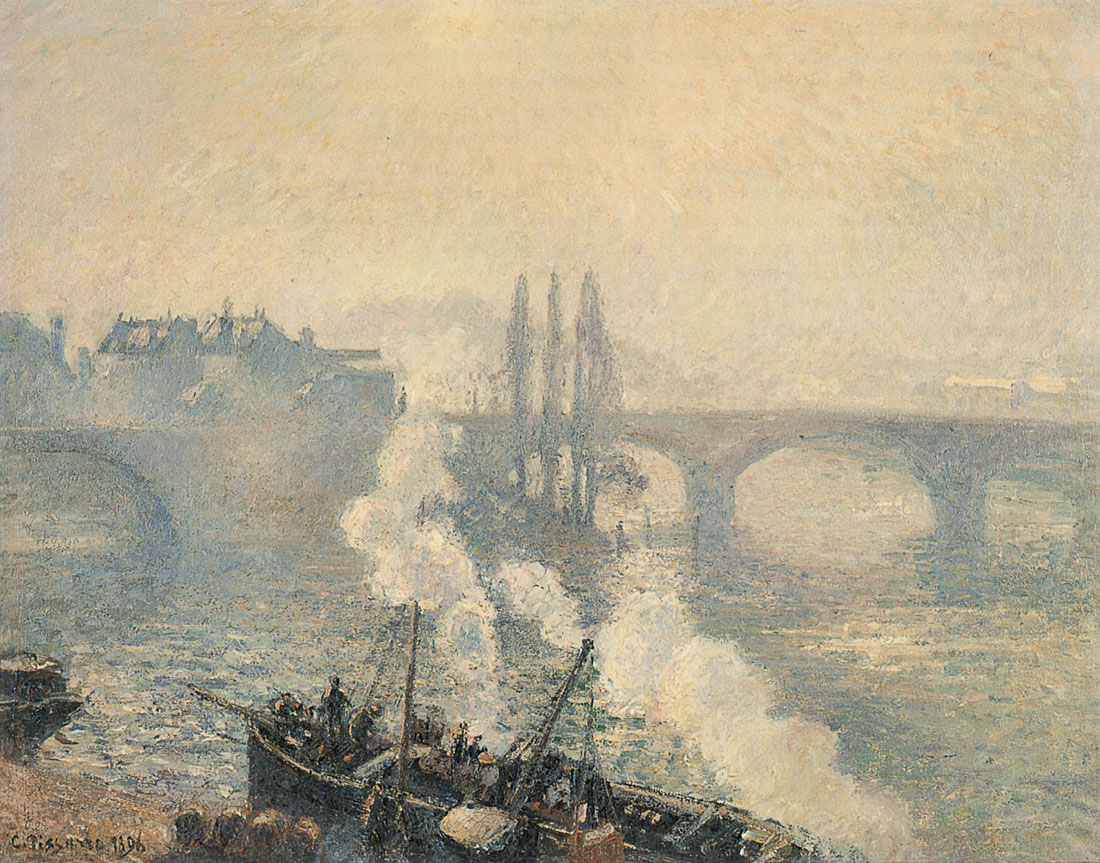

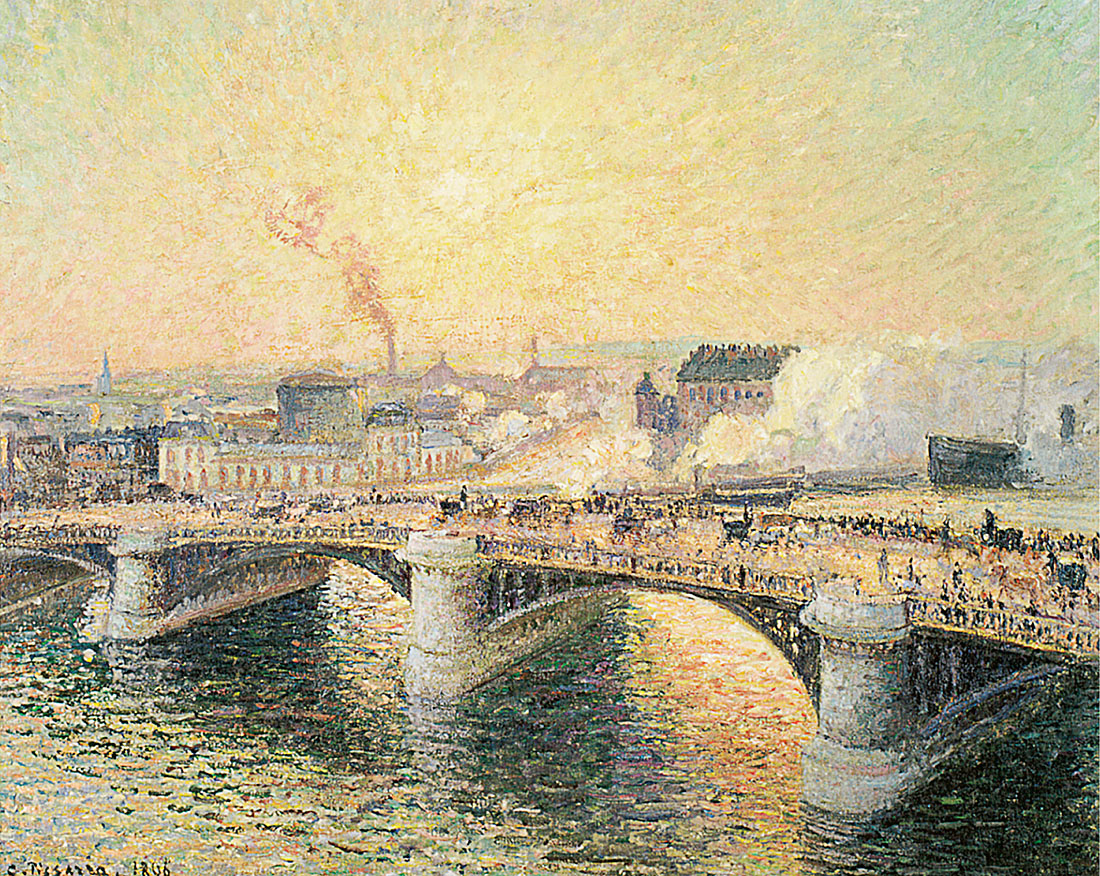

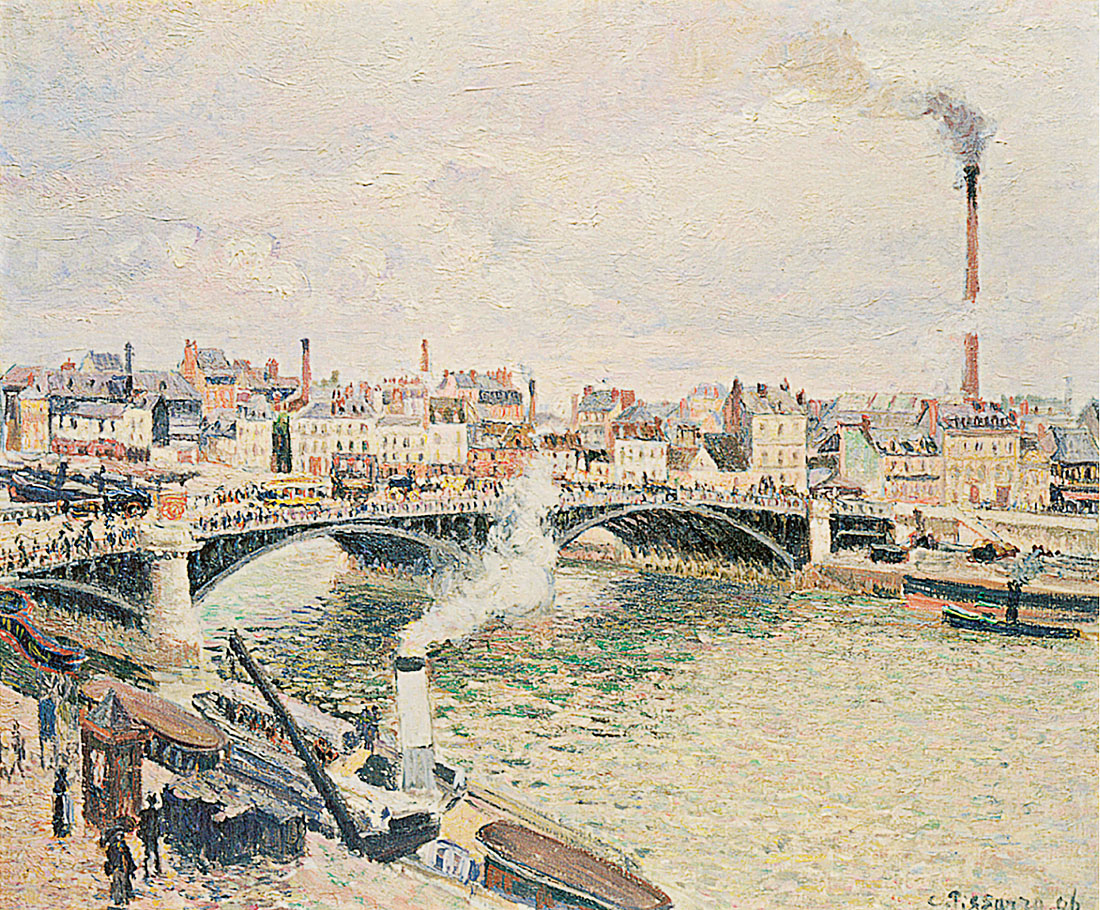

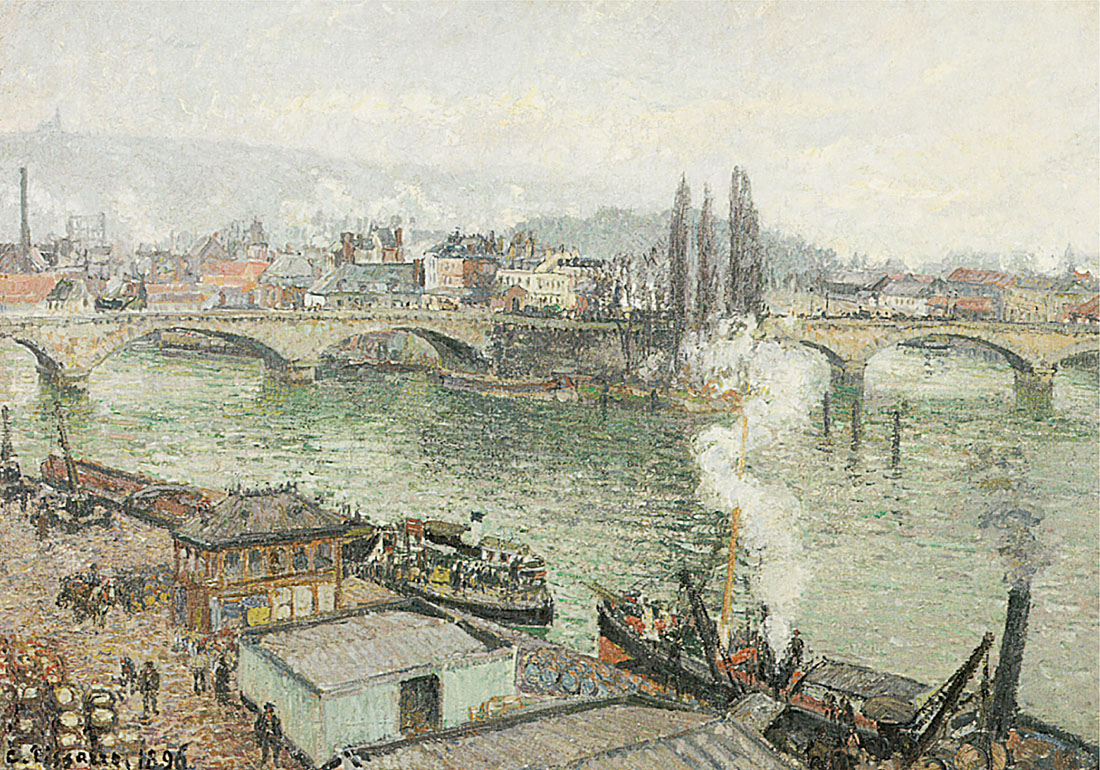

Occasionally Pissarro travelled to London, Brussels, or Rouen. This very lively city, with its port, appealed to him. He painted Rouen for the first time in 1883, then returned there several times in 1896. Settled in the Hotel D’Angleterre, he told his son that the view from his window, on the mezzanine, was magnificent. In February 1896 he became particularly interested in Boieldieu Bridge, or the Great Bridge:

What particularly interests me is a motif with the railroad bridge in wet weather, and a great deal of traffic: vehicles, pedestrians, dock workers, ships, smoke, and mist in the distance – very animated and full of action.

He wrote, “I wanted to render the liveliness of this beehive of activity that is Rouen on the docks.” In this letter he is, in fact, outlining a program for urban landscapes that he meant to implement in his painting point-for-point during the last years of his life. The best view of the Great Bridge was from the windows of the Hotel d’Angleterre, where Pissarro painted enthusiastically The Great Bridge, Rouen, 1896.

I have a motif [...] from my window, the new neighbourhood of Saint-Sever directly across from here, with the hideous Orléans station, sparkling brand-new, and a heap of chimneys, huge ones and tiny ones, with their plumes of smoke.

He described this landscape to Lucien as it appeared on his canvas. “In the foreground, ships and water: to the left of the station is the working-class district, which runs the length of the docks up to the railroad bridge, Boieldieu Bridge. It’s morning, with a delicate, hazy sun.” One has the impression that a winter’s day could be recreated in paint from these notes, down to its very atmosphere.

It’s as lovely as Venice [...], it has an extraordinary character [...]. It’s art – and I’m seeing it through my own sensations. There isn’t only this motif, there are wonders right and left.

Market at Pontoise, 1895

Oil on canvas, 46.4 x 38.4 cm. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

The Boieldieu Bridge in Rouen, Rainy Weather, 1896

Oil on canvas, 73.6 x 91.4 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

The Boieldieu Bridge in Rouen, Sunset, 1896

Oil on canvas, 74.2 x 92.5 cm. Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham

No matter what Pissarro’s attitude might be towards his motif, it remained that of an Impressionist, and the role of weather was in no way least important for him. “The Sun! It’s a rare delicacy at the moment. The canvases I’ve begun with this effect are back in my crate waiting for it to clear up, but the effects of rain never stop”, he wrote from Rouen, “there are even times when I have to keep my windows closed!” For an Impressionist painter, painting a landscape from a window was the same as working in the open air.

In 1885 Pissarro met Georges Seurat (1859-1891) and Paul Signac (1863-1935). For a short interval he and his son Lucien adhered to their “Pointillist”, “neo-Impressionist style,” and both began to paint using small, juxtaposed touches of colour. In the beginning Pissarro was captivated by the way Seurat tackled the lessons of classical art and the science of colour. Pissarro was a man of many enthusiasms, and remained young all his life because of his temperament. He painted a whole series of Pointillist works in the manner of Seurat and Signac, but in 1888 he began to caution Signac about the dangers of following “Pointillism” blindly. He advised him to make use of science, which belonged to everyone, but to preserve his artist’s sensibility. He knew it would be impossible to change Seurat’s view of the correctness of his new system of painting, and that the issues Seurat was raising would assuredly be dealt with. Still, “Old Man Pissarro” had too much respect for Signac not to try to warn him. Pissarro was convinced that creativity was superior to theory. On that basis he came to the conclusion that “Pointillism” wasn’t right for him, since the impression it produced had a lifeless monotony to it.

During the 1890s Pissarro was forced to interrupt his work in the countryside: due to an eye disease he could no longer work in the open air. In Paris he made a great many prints and painted fans – this brought in a bit of money. At the end of the century there was a craze for Japanese style – “le japonisme”, which was one of the decorative elements of “Art Nouveau” ornamentation. In 1893 all of Paris was swooning over the exhibition by the Japanese Painter Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). Still, Pissarro remained an Impressionist in his fan paintings. He described to his son Lucien one of these fans which, he said, had produced something quite unexpected: a red setting sun, like an aurora borealis, a trail of pearl-grey mist, and, in this mist, the blurry contours of cows. He drew these fans on Japanese paper, and the influence of the Japanese masters is evident.

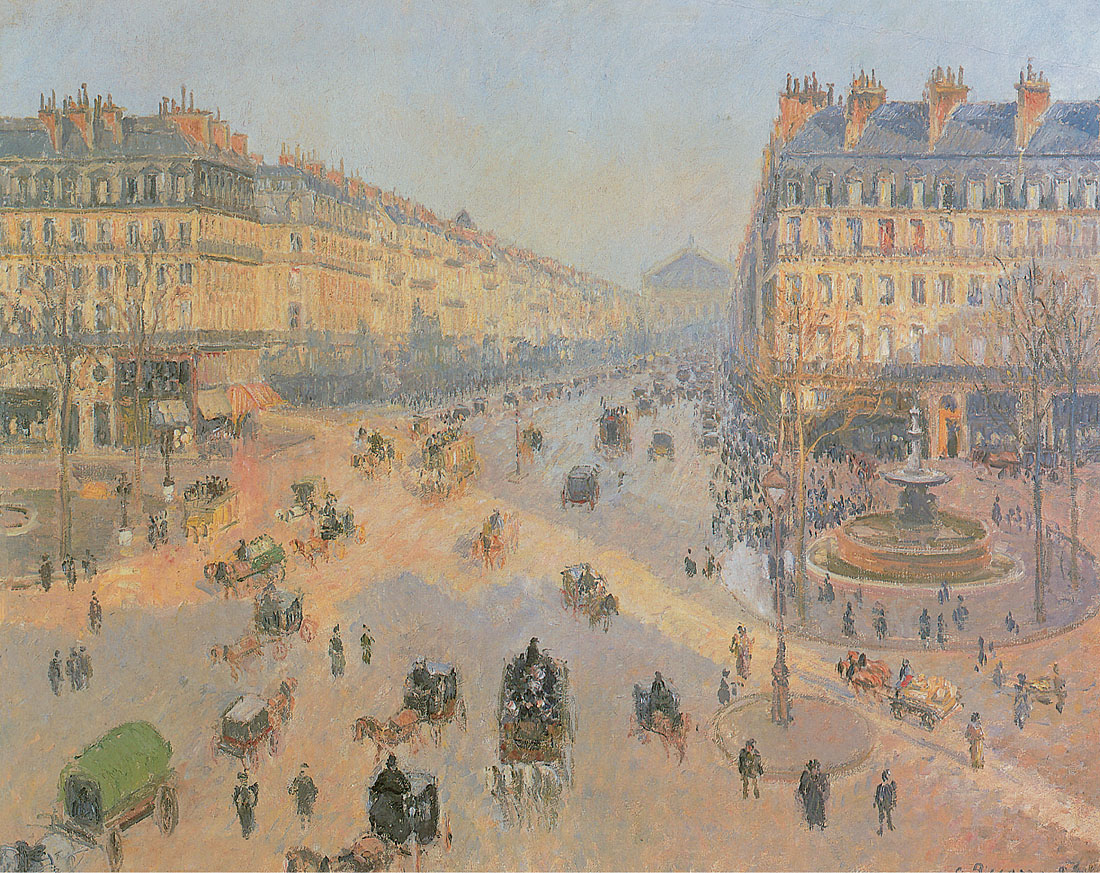

In the 1890s Pissarro began to paint the Parisian landscapes that were to assure his reputation as an urban landscape painter. He found a way to reconcile his preference for open-air painting with his doctors’ prohibitions: he would rent a room somewhere, on as high a floor as possible, preferably an attic, from which a magnificent panorama of Paris could be seen – “I want to sleep near the stars, like the old astrologers /“ wrote Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), “while I’m chastely writing my pastoral verse / From high up in my attic, my chin cupped in my hands… / I’ll see them talking and singing in the workshop.” Clearly it was impossible to discern details, but the painter could detect the pulse of Paris in its continuously animated streets. He painted close to the window, in the same manner as in Rouen or the open air of the countryside. He began and completed his landscape in just one session, like in the outdoors, and all the while his eyes were protected from exposure to the wind. He had previously painted isolated urban views on occasion: Boulevard Rochechouart in 1878, and a snowy effect in The Outer Boulevards, also from 1878. Now he painted Rue Saint-Lazare. Trains starting out from Éragny arrived at Saint-Lazare station, and Pissarro usually entered the city by this route. In 1893 he settled in to the Hotel Garnier on Rue Saint-Lazare. He painted four views of this street from the hotel window that were the start of his large series of Parisian landscapes. Next came an opportunity of a sort he could only have dreamt of: “I’m leaving again on the tenth of the month, for Paris again, this time to do a series there of the Boulevard des Italiens,” he wrote to his son from Éragny in February 1897.

I’ve decided on a spacious room at the Grand Hotel de Russie, One Rue Drouot, from where I can see the whole succession of boulevards almost all the way to Porte Saint-Denis, or as far as Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle, anyway.

From this window he began to paint the long ribbon of broad boulevards that follow one after another, in different weather, in different situations, and at different times of the day. He wanted to see the crowds on holiday from above, which would introduce a new rhythm and new colour into the landscape. “Here I am, all settled in and covering some large canvases,” he wrote a few days later. “I’m going to try to prepare one or two in order to do the crowds on the day of Mardi Gras. I don’t know yet what will happen: I truly hope the streamers don’t bother me.” Pissarro would prepare a canvas with the perspective of the boulevard, then paint it at the moment he wished to set down on this canvas. He painted a total of fifteen variations using Boulevard Montmartre. Certain canvases were of the everyday boulevard, on workdays, with the vehicles coming and going, while on the sidewalks the dark stream of unhurried pedestrians flow by Boulevard Montmartre in Paris, 1897. In others, this same boulevard is flooded with a stream of bright colours: it is the Carnival celebration going by (Boulevard Montmartre, Mardi Gras, 1897).

I have a large number of things in progress. On Mardi-Gras I did the boulevards with the crowds and the Boeuf-Gras parade, with the sun’s effects on the streamers and the trees, and the crowds in the shadow.

In this series Pissarro continued and elaborated on the image of the new Paris of their time, which Monet had begun in his Boulevard des Capucines (1873). He switched hotels and switched apartments, but his motif always remained Haussmann’s Paris. “I forgot to inform you that I have found a room in the Grand Hotel du Louvre with a superb view of the Avenue de L’Opéra and the corner of the Place du Palais Royal! Very nice to do!” he wrote in 1897.

It may not be very aesthetically pleasing, but I am delighted to be able to try and do the smaller streets of Paris which are commonly thought of as ugly, but which are so silvery, so luminous and so lively. It’s entirely different from the boulevards. They’re completely modern.

Morning, An Overcast Day, Rouen, 1896

Oil on canvas, 54.3 x 65.1 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Corneille Bridge in Rouen, Dull Weather, 1896

Oil on canvas, 66.1 x 91.5 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Boulevard Montmartre in Paris, 1897

Oil on canvas, 74 x 92.8 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Boulevard des Italiens, Morning, Sunlight, 1897

Oil on canvas, 73.2 x 92.1 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Mardi Gras, Sunset, Boulevard Montmartre, 1897

Oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm. Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Winterthur

Rue de l’Épicerie, Rouen (Effect of Sunlight), 1898

Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 65.1 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Avenue de l’Opéra, Sunny Morning in Winter, 1898

Oil on canvas, 73 x 91.8 cm. Musée des Beaux-arts, Reims

The Great Bridge, Rouen, Rain Effect, 1898

Oil on canvas, 73 x 92 cm. Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe

The Rue de l’Épicerie, Rouen, Morning, Grey Weather, 1898

Oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm. Private collection

The Place du Théâtre Français, 1898

Oil on canvas, 72.4 x 92.7 cm. Mr. and Mrs. George Gard De Sylva Collection, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

The Boieldieu Bridge and the Gare d’ Orléans station Rouen, 5 o’clock in the morning, 1898

Oil on canvas, 64.4 x 80.5 cm. Private collection

The Quai de la Bourse, Rouen, rain, 1898

Oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm. Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de Genève, Geneva

He continued to work according to the same method, preparing the landscape’s composition in advance. “Here I am, I moved in yesterday,” he continued in the letter to his son. “I have two large rooms and nice large windows from which I can see the Avenue de L’Opéra. The motif is very fine, very painterly. I have already begun two canvases.” The point of view looking down on the city permitted Pissarro to use new composition methods, which the Impressionists had learned from the model of Japanese prints. If he painted a street that went on for a distance, the perspective remained a classical, linear one (Avenue de l’Opéra, Sunny Morning in Winter). If he was looking out from his attic at the Théâtre Français, it would spread out over the canvas on one plane only, right to its upper edge, leaving no space for the sky. The square is sprinkled with little figures of men and women, as is sometimes the case in Pieter Breughel’s (1525/1530-1569) compositions. Though, in a Pissarro, these figures are most often done with two or three touches of paint, as if carelessly applied to the canvases. Each of them precisely renders the characteristic movement of a pedestrian. His pedestrians swarm through the square and its vicinity, running to cross the streets, mounting the public transports (The Place du Théâtre Français). From high above it, Pissarro reproduced the city’s circulation and rhythm with the same sensitivity Monet demonstrated for capturing atmospheric changes. After Monet’s series of “Stations” and “Rouen Cathedrals”, Pissarro’s urban series finally appeared in the exhibitions: twelve “Passages [Alleys]” and seven or eight “Boulevards.” At the dawn of the twentieth century Pissarro painted the Tuileries Gardens, from an attic as always. In one of these canvases, behind the garden and the Seine, the Gare d’Orsay station can be seen, still under construction. He was not satisfied with the works of this period. He wrote to Claude Monet that those who were praising his landscapes of the Tuileries Gardens were being too indulgent towards him: “I’m not satisfied with it. I haven’t worked much. I’m battling old age.” He was pleased to have found a good workplace, near the Pont-Neuf, with a magnificent view. In 1901 Pissarro worked in Dieppe. In this old maritime city he saw the natural context he needed: the lively activity of the colourful crowd at a fair around the huge Gothic cathedral (The Fair at Dieppe, Sunny Afternoon).

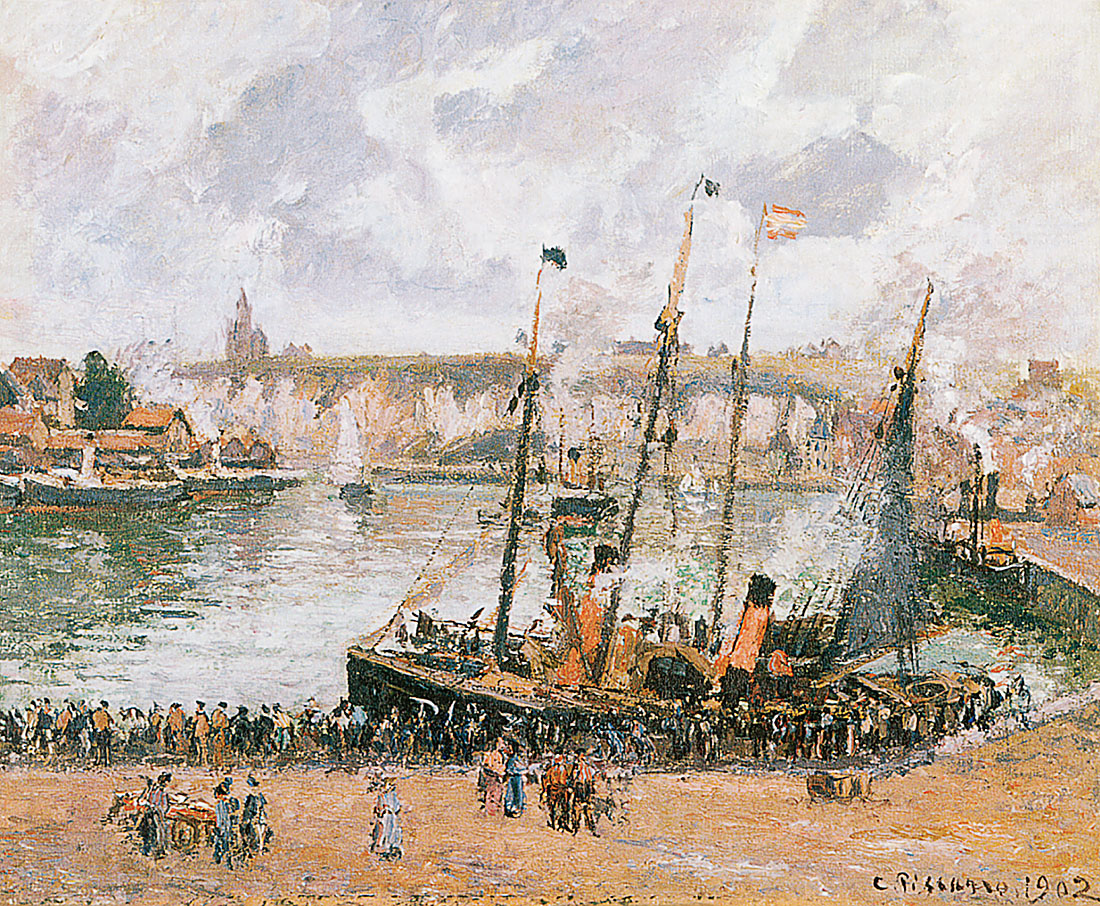

In July 1903 he stayed at the Hotel Saint-Siméon in Normandy, the previous site of a farm which had been a meeting place for Courbet, Daubigny, Jongkind, Boudin, and Monet. The entrancing little city of Honfleur disappointed Pissarro: the elegant villas that had been constructed there, along with the too-manicured, well-kept streets, had spoiled the landscape. Le Havre, on the other hand, inspired him. The old Impressionist, to whom life had taught wisdom, was no longer interested in the details of the landscape. He sought to penetrate to what was essential, which is what he had aspired to throughout his life as a painter. “I only see patches of colour now,” he said.

When I begin a painting, the first thing I try to get down is the accord. Between the sky, and the land and this water, there is necessarily a relationship of accord, and that is the great problem in painting [...] The great problem to resolve is to bring everything, even the smallest details of the painting, back into harmony with the ensemble, by which I mean the accord.

Pissarro’s last apartment in Paris was on the Quai Voltaire. His last landscapes represent the perspective of the dock, slightly curved in a circular arc, with the dome of the Institut de France, the booksellers’ stalls, and the hurried passersby. This is where the painter died on 13 November 1903. Pissarro was a relentless worker. Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917) wrote of him that he was happy simply because, in the course of his seventy-three years of life, he had one great and noble passion: work. With a serene smile spreading beneath his white beard, he had told the writer that work was wonderful for regulating mental and physical health: when he was working he forgot all his sorrows, all his troubles. His paintings sold as poorly as those of the other Impressionists, and his life was difficult, but he had always shown the same warmth towards his friends. He rejoiced at Renoir’s luck when he managed to exhibit at the Salon. He mourned the death of Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), whose talents he appreciated and who, he said, had swept the Impressionist group off of their feet with her talent and feminine charm, but who was practically unknown to the public. As in the past, he stayed active in public life. During Zola’s trial he wrote that France was seriously ailing, and, in a short note to Zola, he expressed his admiration. He signed a protest with Claude Monet, Octave Mirbeau, and others. Pissarro himself, like Sisley, was usually mentioned as part of a general survey, among other landscape painters, but he accepted this with serenity. He said this affected him little, that the works were there and that they, at least, would remain. In a letter written 22 September 1903, shortly before his death, Pissarro bemoaned the fact that art lovers were not pressing to buy the paintings of the Impressionists. “It will take some more time for even our friends to understand us.” It took as long as it had for the other Impressionists before he began to be recognised. It was not until after the painter’s death that Théodore Duret, in 1906, wrote that the fields Pissarro represented had a soul, that they conveyed a deep sense of enchantment, and that little by little his contemporaries had learned to appreciate him. It was only later that evaluations of the history of Impressionism granted Pissarro the position that was his due: Georges Lecomte (1867-1958) characterised him as the founder of Impressionism, and Thadée Natanson (1868-1951), editor of The White Revue, called him the “apostle of Impressionism.”

The Quai de la Bourse in Rouen, Sunset, 1898

Oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm. Linda Gale Sampson Collection

The Tuileries Gardens, Rainy Weather, 1899

Oil on canvas, 65 x 92 cm. Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, Oxford

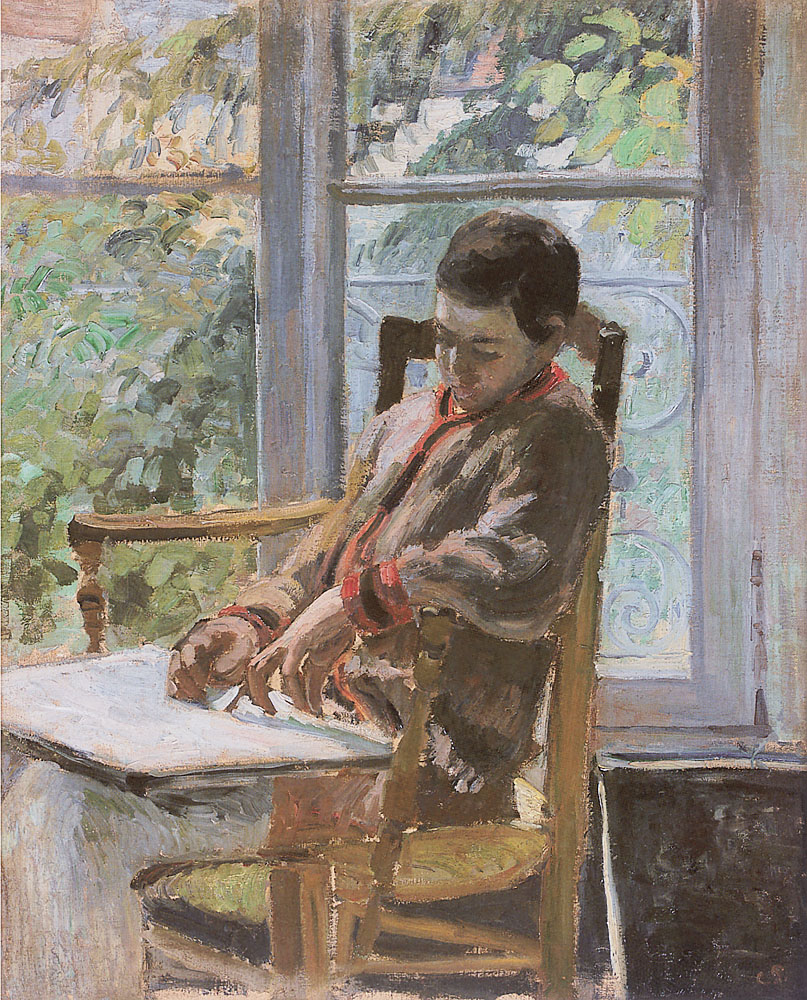

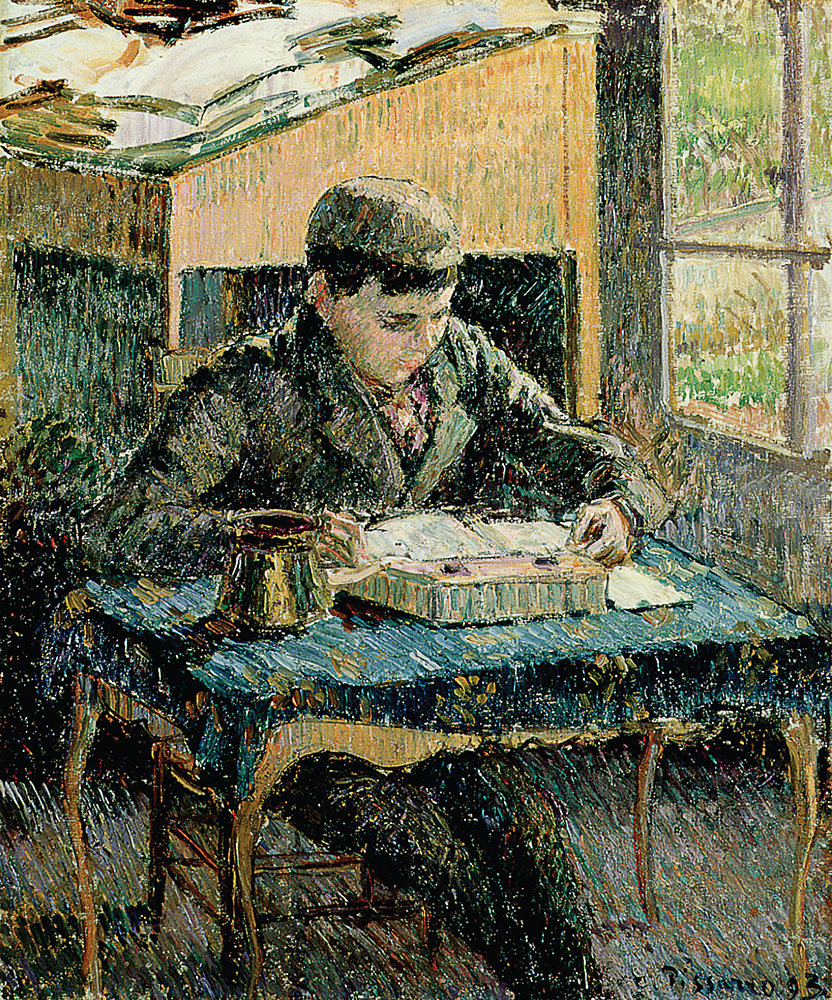

Jeanne Pissarro, Called Cocotte, Reading, 1899

Oil on canvas, 56 x 67 cm. Collection of Ann and Gordon Getty

The Fair at Dieppe, Sunny Afternoon, 1901

Oil on canvas, 73.5 x 92.1 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

Outer Harbour of Dieppe, Afternoon, Sunshine, 1902

Oil on canvas, 53.3 x 65 cm. Château-musée de Dieppe, Dieppe

Outer Harbour of Dieppe, Afternoon, Bright Weather, 1902

Oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm. Private collection

Outer Harbour of Dieppe, Cloudy Weather and Sunshine, 1902

Oil on canvas, 60 x 73 cm. Private collection, Switzerland

Horses and Carts before the Dock at Low Tide, Dieppe, 1902

Oil on canvas, 54.9 x 65.1 cm. Private collection

Outer Harbour of Dieppe, Morning, Cloudy Weather, 1902

Oil on canvas, 46.7 x 55.2 cm. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco

Harbour at Dieppe, Cloudy Weather and Rain, 1902

Oil on canvas, 52.1 x 64.8 cm. Worcester Art Museum, Worcester (Massachusetts)