I made art according to myself. I made it with my eyes open to the wonders of the visible world, with the constant worry of obeying the laws of nature and life, and whatever else can be said about it. I also made it with the adoration of some masters who lead me to the cult of beauty. Art is of supreme importance, elevated, salutary, and sacred, it blossoms; for the amateur it only produces a delicious pleasure, but for the artist, it creates with tormentnew seeds from the grain.

I seem to have meekly surrendered to the secret laws which have led me to shape, somehow as best I could, and according to my dreams, the things which I fully threw myself into. If this art has come against the art of others (which I do not believe it has), it has given me an audience that withstands time, and friendships of quality and kindness which are sweet and rewarding. The remarks I make here will help more with the understanding of the art than of all I could say about my concepts and technique. Art also partakes in the events of life.

This will be the only excuse to talk exclusively about myself.

Childhood

My father would often say to me “Look at these clouds, do you make out the changing shapes like I do?” And then he would show me in the changing skies apparitions of strange beings, wild and wonderful. He loved nature and would often talk to me of the pleasure he felt in the savannas, in America, in the vast forests he would clear. Born on the outskirts of the small town of Libourne, he left for New Orleans when he was young, at the time of the wars of the First Empire. His ambition was to make his fortune to return to his homeland so as to live a life in comfort, which no longer existed at that time.

After having explored and cleared forests, he quickly amassed a large enough fortune and married a French woman. Five or six years into their marriage, with me, the second fruit of their union, already conceived and about to be born they returned to France. It was a few weeks after their return that I entered the world in Bordeaux on the April 20, 1840. I was brought to a nanny in the country, to a place which had a great deal of influence upon my childhood and youth.

In this place I speak of, situated between the vines of Médoc and the sea, you are alone. The ocean which once covered these deserted areas has left a whisper of abandonment in the dryness of the sand. It is across these arid plains that I passed for the first time as a child, before being fully conscious and aged just two days old. I have crossed them many times since: the oxen were replaced by horses, and then the horses by the iron on the tracks along with the engines of the modern world – which I do not denounce.

In these regions of Médoc my father owned an old estate surrounded by vines and uncultivated land, with large trees, eternal brooms, and heather close to the château. I was confined there in that old manor, after the nanny was no longer needed, under the charge of an old uncle, the keeper of the estate, whose good-natured blue-eyed features hold a special place in the memories of my childhood. If I try to relive those memories to the point of reviving faraway states through a consciousness that is now defunct, I become weak and sad.

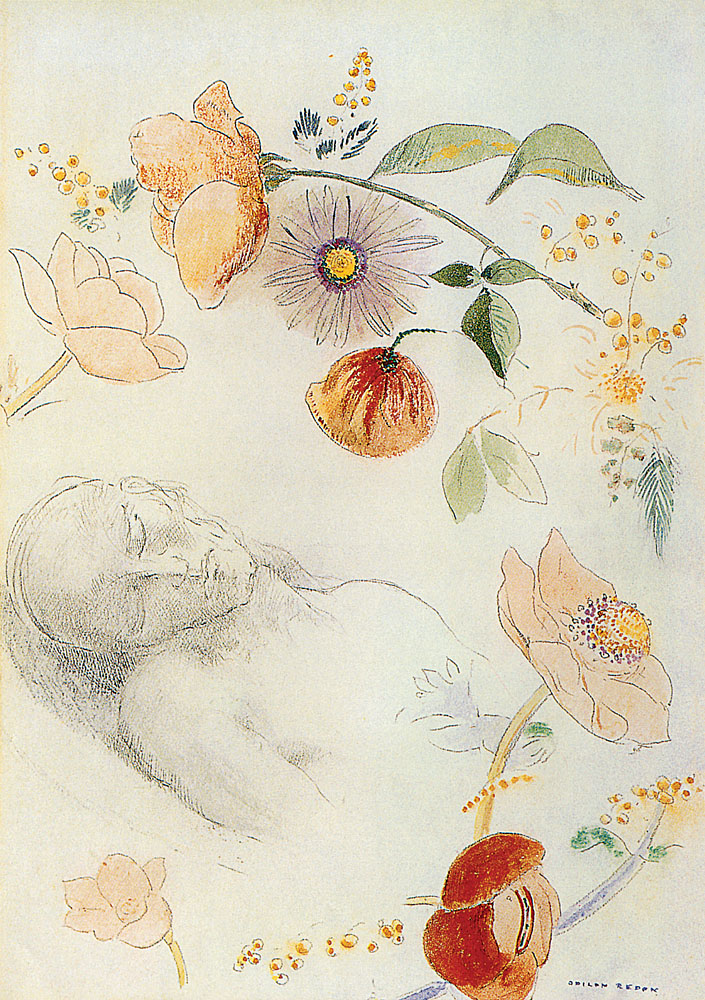

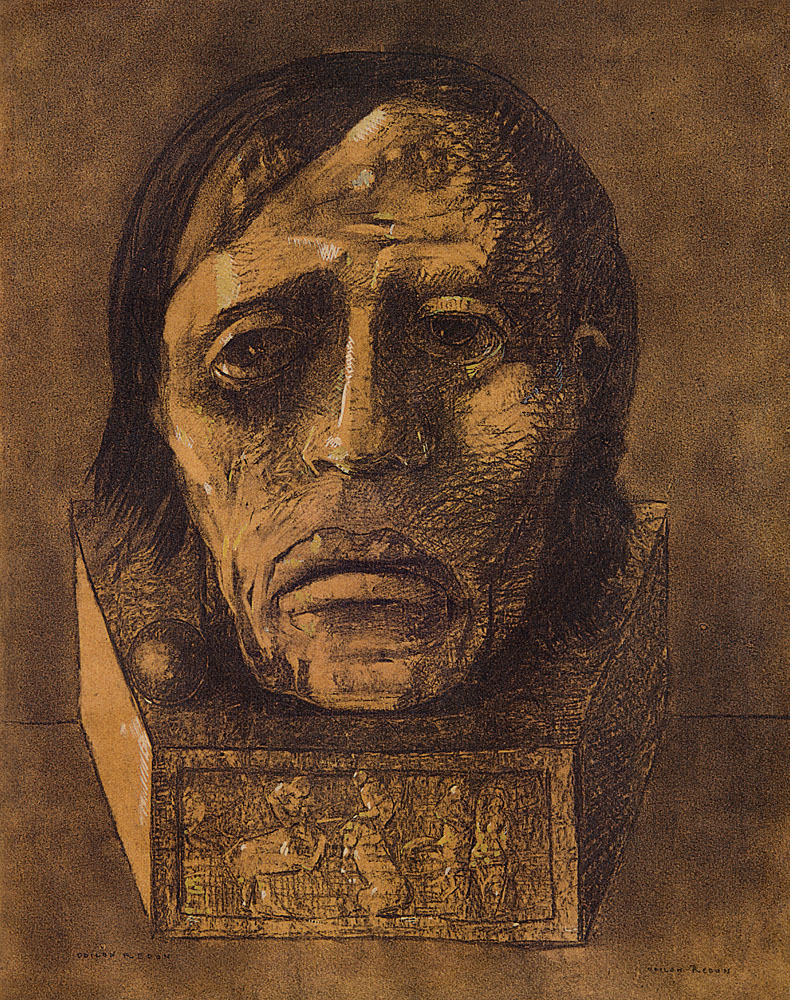

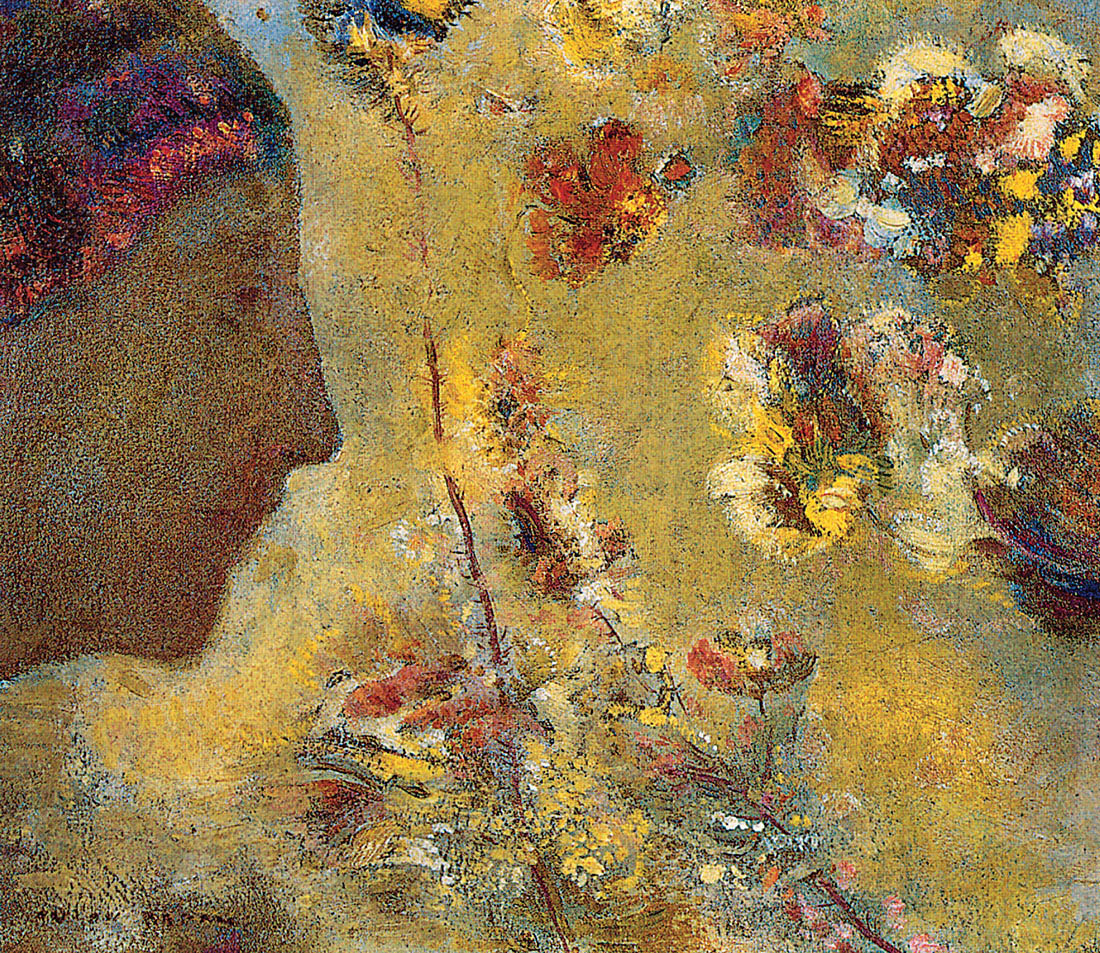

Bust of a Man with Eyes Closed, Surrounded by Flowers, date unknown

Watercolour and black lead pencil on paper, 25.5 x 17.7 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris

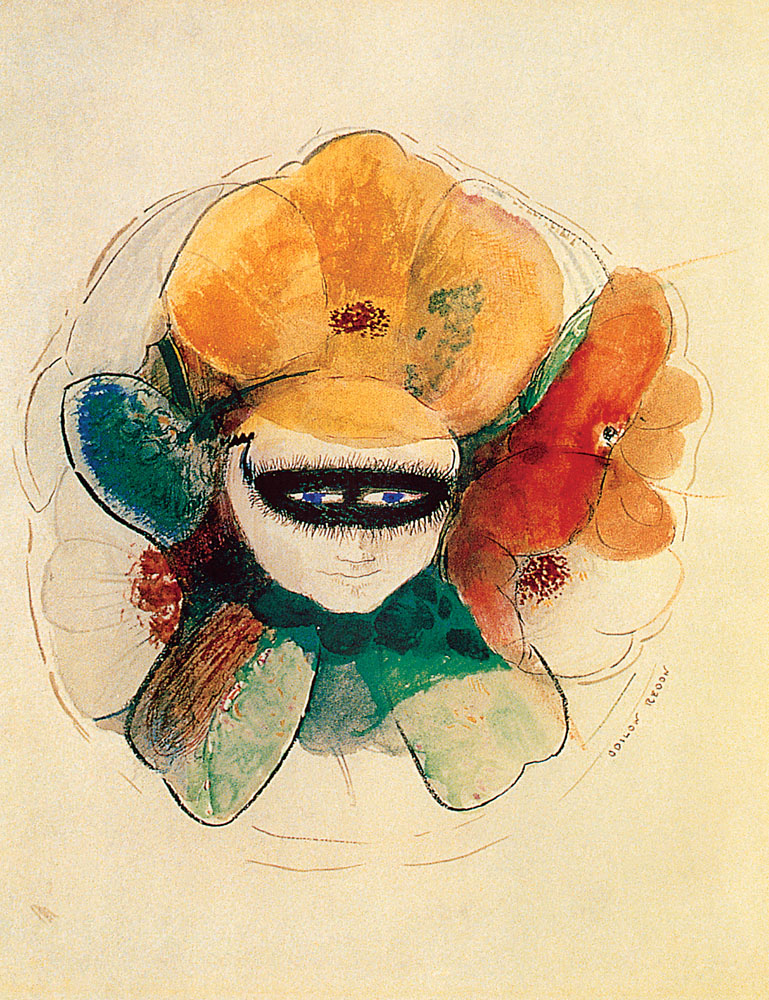

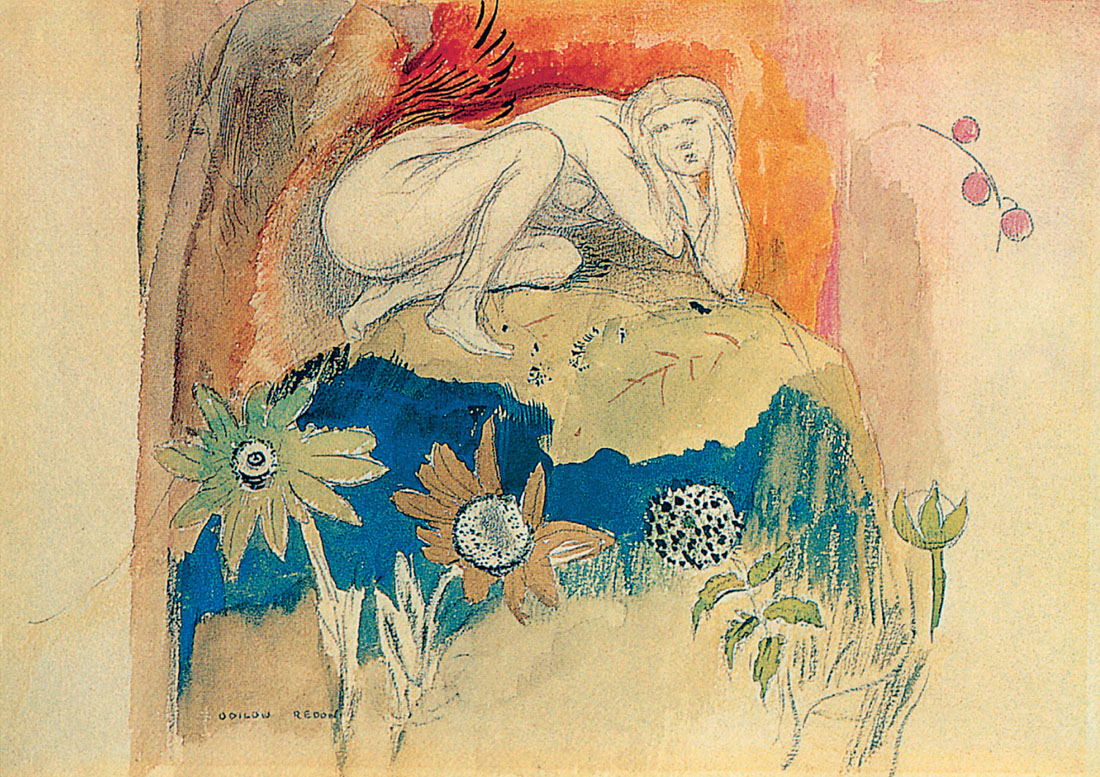

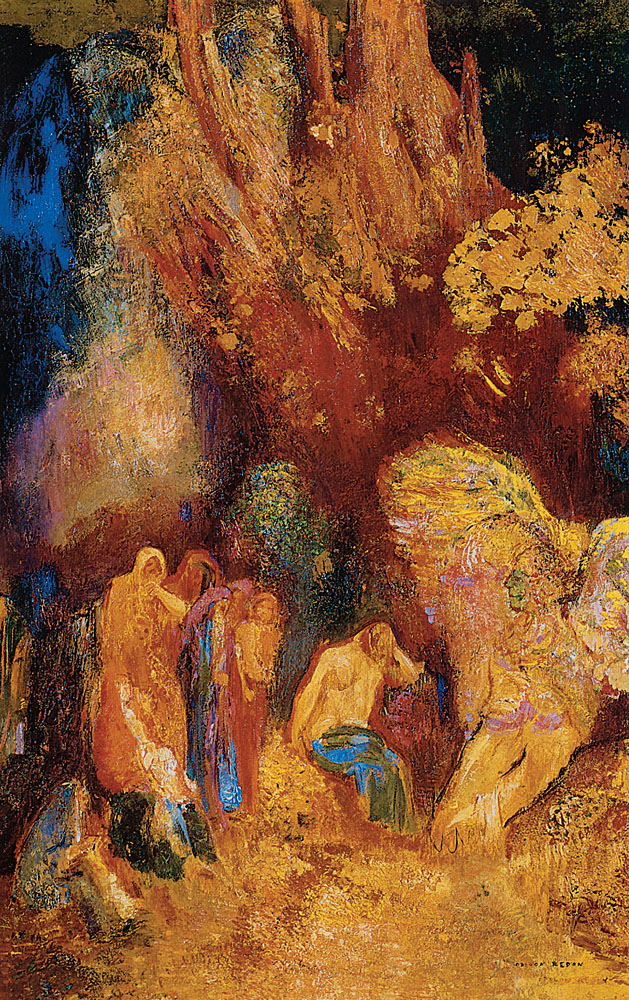

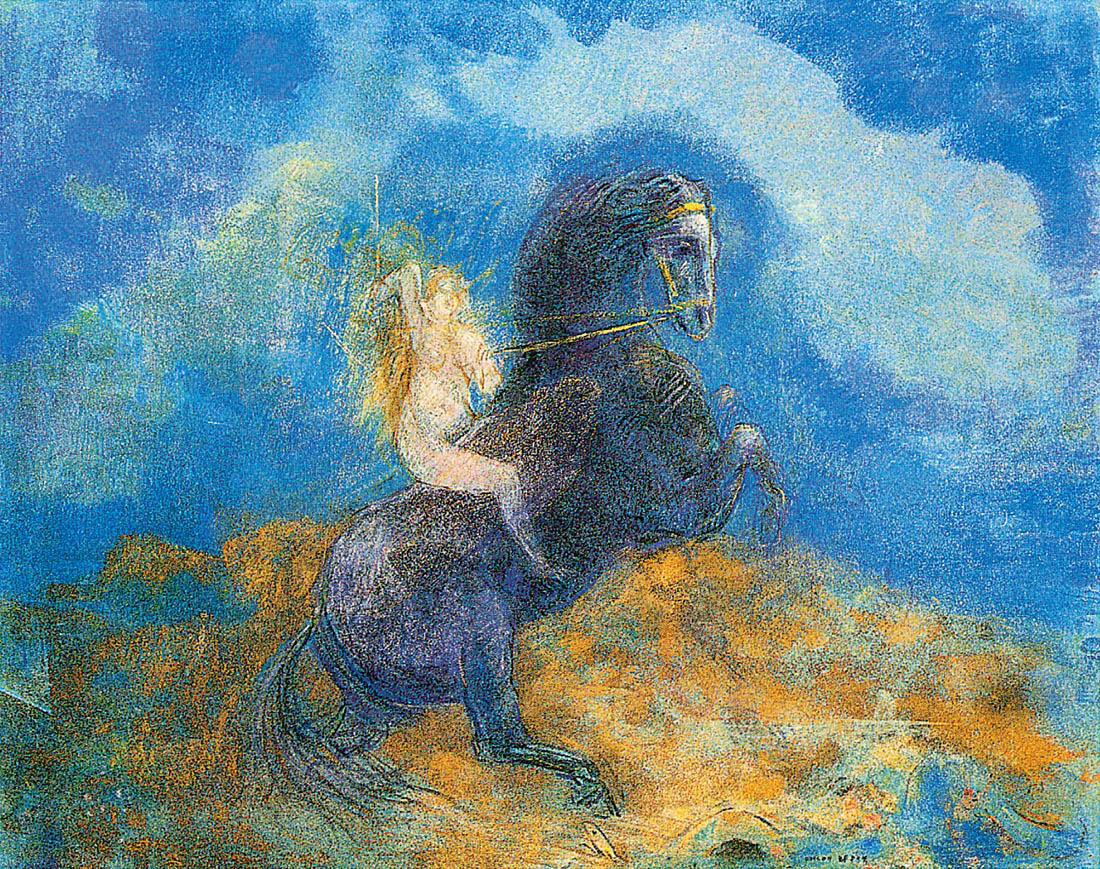

Temptation, date unknown

Watercolour and pencil, 17.7 x 25.1 cm. The Ian Woodner Family Collection, New York

I can observe myself taking pleasure in the silence. As a child, I sought out the shadows; I remember taking great joy in hiding under the big curtains, in the dark corners of the house, in my playroom. And out of doors, on the land, what fascination the sky held for me! Much later still – I don’t dare tell you at what age as you would think me not a true man – I would spend hours, or rather the whole day, sprawled out on the ground in a deserted part of the countryside, watching the clouds go by, following with an infinite pleasure, the magical radiance of their fleeting changes.

I was peaceful, not a fighter, inept at the business of roaming the fields where the others brought me. I was more likely confined to the courtyards or the garden and busied with quiet games. Besides, I was sick and feeble, always surrounded by caregivers; they were prescribed to avoid cerebral fatigue. Aged seven I spent a year in Paris and I can recall long walks with the old lady who accompanied me. It is at that age that I experienced the museums. The paintings of tragedies were imprinted in my memory; I can only recall representations of a violent life, in excess; that is what struck me.

I had a sickly childhood and that is the reason I was sent to school much later, aged eleven, I think. This is the saddest and most pathetic part of my childhood. I think I can say that from eleven to eighteen years of age, I only felt resentment for my studies. They were imbalanced, lacking development, lacking method, taking place in two boarding schools in Bordeaux, and with little Latin. I would only get a new lease of life the days we were allowed out, during which I would keep myself busy.

I had copied the lithographs of that time according to the first styles of hatching.

Great emotions were felt at the time of my first communion, under the arches of the Saint-Seurin church; the chants thrilled me, they were truly my first revelation of art, apart from the music I had heard many times with my family. It was this way until adolescence, the divine adolescence. The mindset of which is lost forever! I would attend church beaming on Sundays or get close to the outside of the apse, enticed by the irresistibility of the divine chants.

By preference I went to the poor neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the city where the churches were packed and the devotion was more natural and real. Was this from a sense of harmony with the people I loved, or the crowds that I still love? I have since discovered a supreme joy in Beethoven, but it seems to have taken all the despair that humanity has accumulated and changed it: to the Ninth Symphony we add our miserable joy.

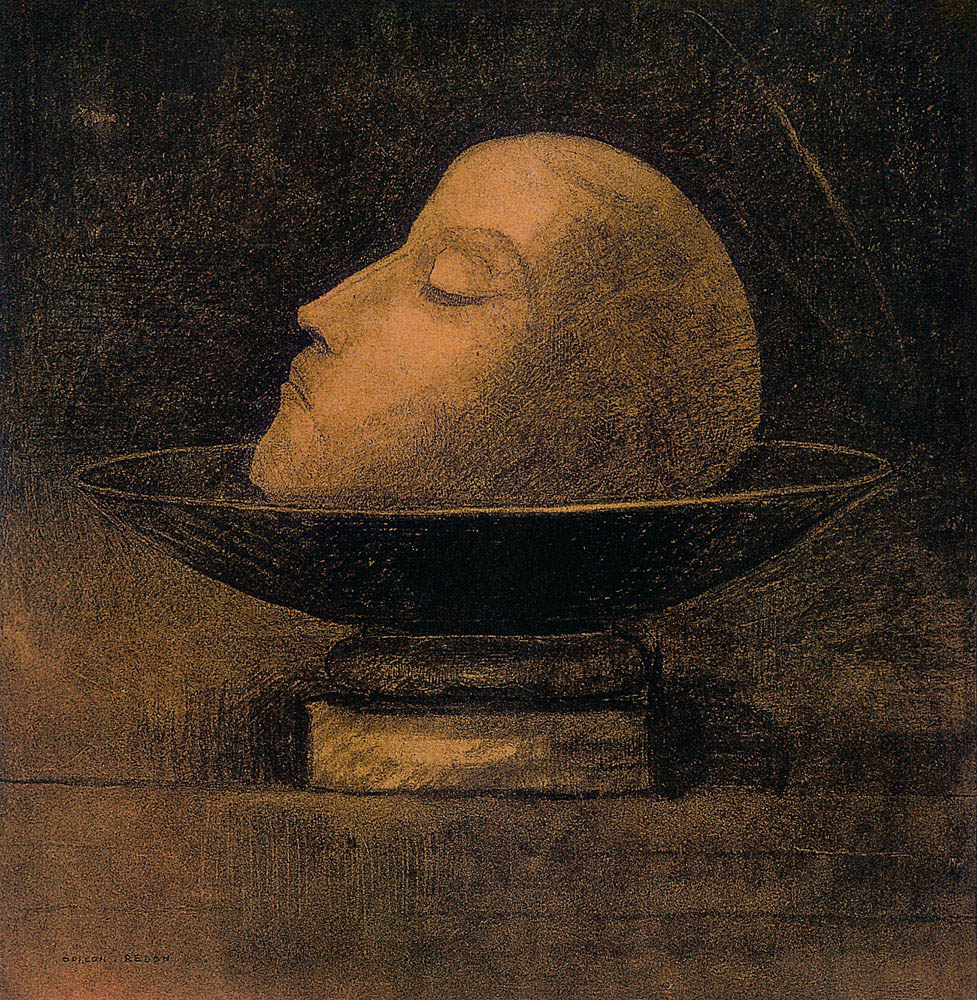

Blossoming (plate Nº 1), from In the Dream, 1879

Lithograph, 32.8 x 27.5 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

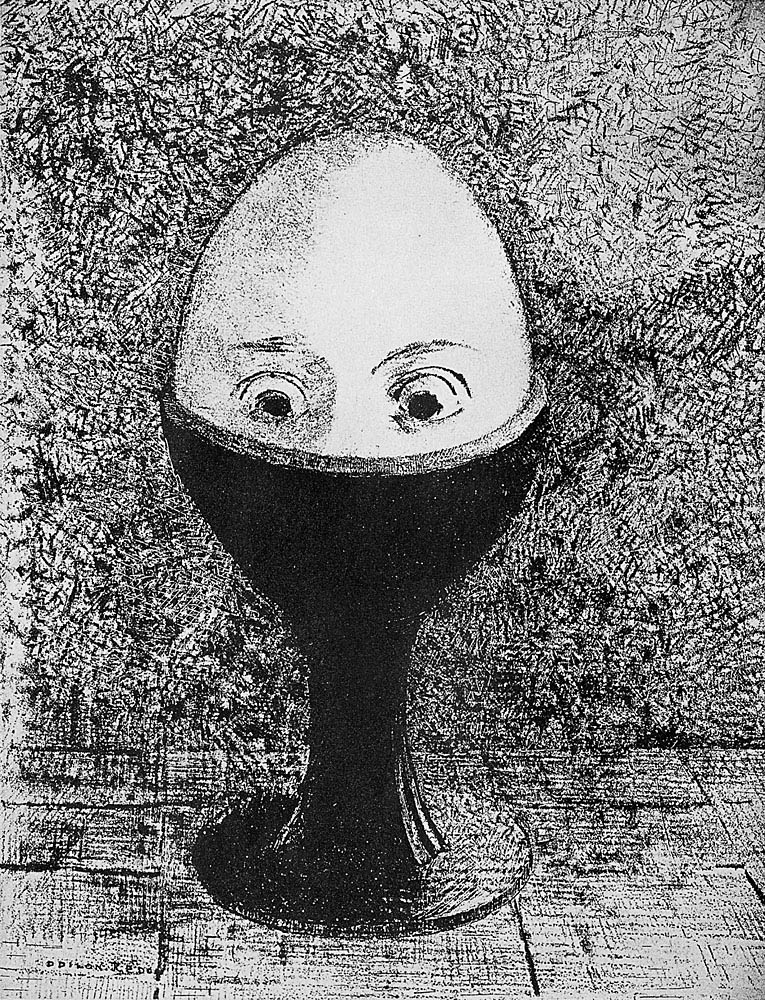

Germination (plate Nº 2), from In the Dream, 1879

Lithograph, 32.8 x 25.7 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Gnome (plate Nº 6), from In the Dream, 1879

Lithograph, 27.2 x 22 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Artistic Education

When I was about fifteen years old I was granted drawing lessons with a teacher at whose home I would go work at on my days off from school. He was a distinguished watercolourist and very much an artist. His first words to me – which I will never forget – were to advise me that I too was an artist and to never allow myself to make even a single mark with a pencil if my sensitivity and reasoning were not present. He had me studying, what he called studies of nature, where I would have to transcribe the laws of static and light which had struck me. He loathed the execution of any practical experience.

In his analyses of the copies I would make, a subtle and penetrating process, he would demonstrate an acumen in his dissection and explanations, which then quite surprised me but that I now understand. He had in his possession some watercolours from the English masters that he admired greatly. He would make me make copies of them. Extremely independent, he would let me go in my own direction. He considered a good omen the shakes and fevers that Delacroix’s passionate and exalted canvases gave me.

Many great artists sent their work to the open exhibitions he held in the province during this time. This is how I was able to see the works of Millet, Corot, and Delacroix, as well as the early work of Gustave Moreau, all in Bordeaux. My teacher would speak to me before them as the poet he was, and my enthusiasm escalated. I owe many of the primary advances in my senses to these teachings, the best and most decisive ones without a doubt; and I believe that for me they are worth much more than the education from a state school.

Later when I went to Paris to try my hand at a more comprehensive educational system, it was too late, luckily; the job had already been done. I have hardly strayed since from the influences of this first romantic and enthusiastic teacher. It is with him that I learnt the essential laws of design; I can hear the laws of creation, its measures, its rhythm; this organism of art that can be learnt from neither rules nor formulae, but that is spread and communicated through the harmony between a master and a student engaging together.

I also created paintings from prints, and this with genuine pleasure. If I was permitted to recommence my artistic education today, I think that I would make many copies of the human body; a necessity we only recognise much later. At sixty years of age Delacroix said that if he were to start his career again, he would only study the skeleton (this is indeed the confession of an imaginative painter); he had for the first time come into the possession of one. It is said that Michelangelo purposely began to study anatomy at the age of thirty or forty.

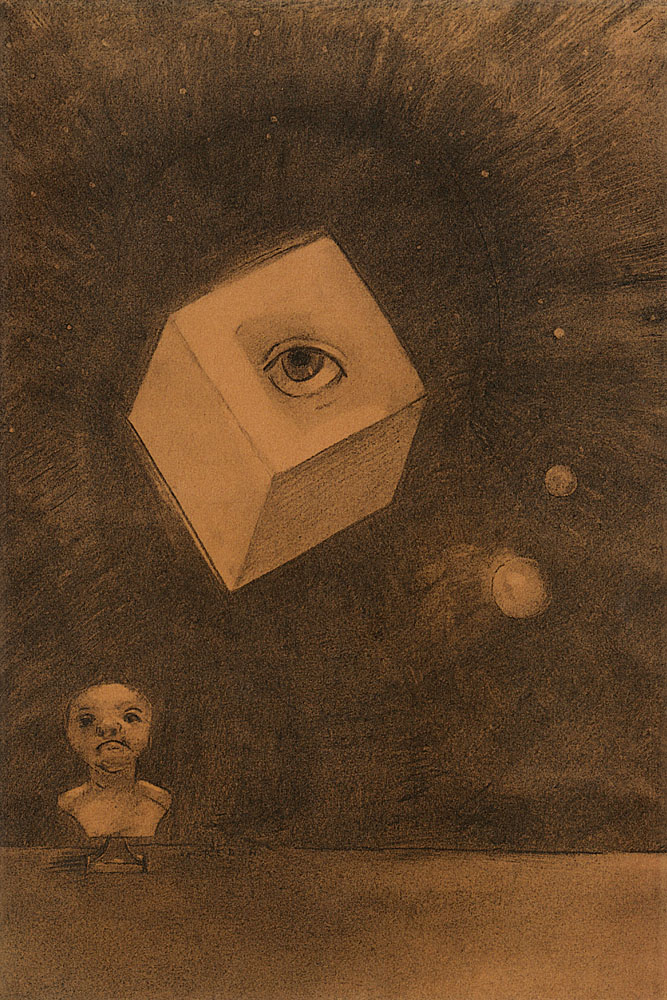

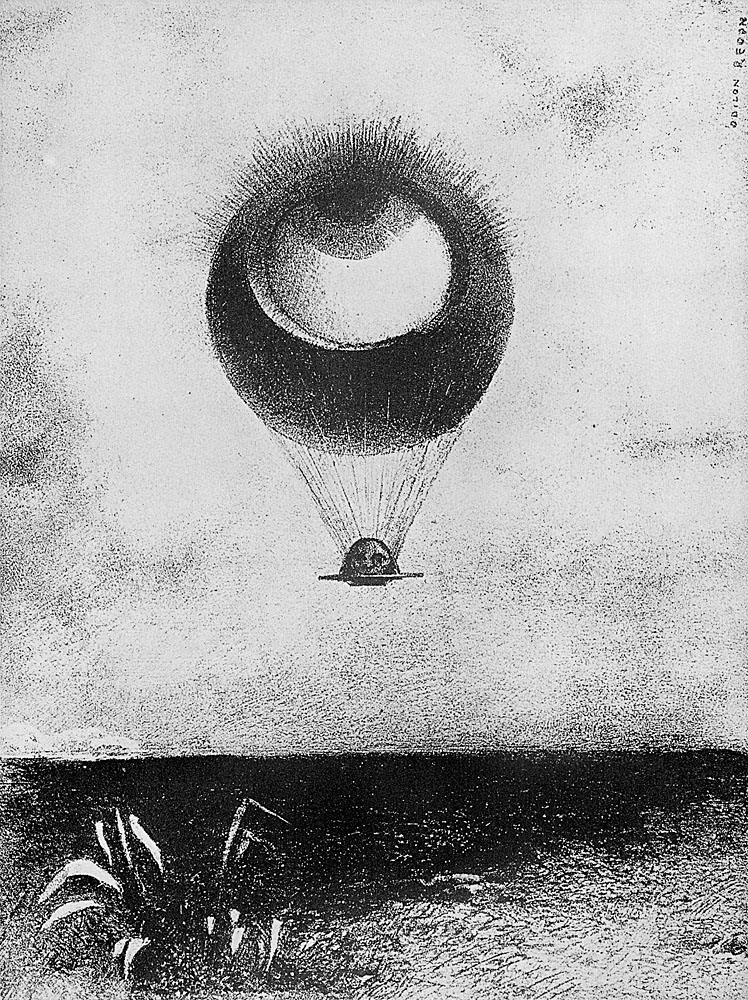

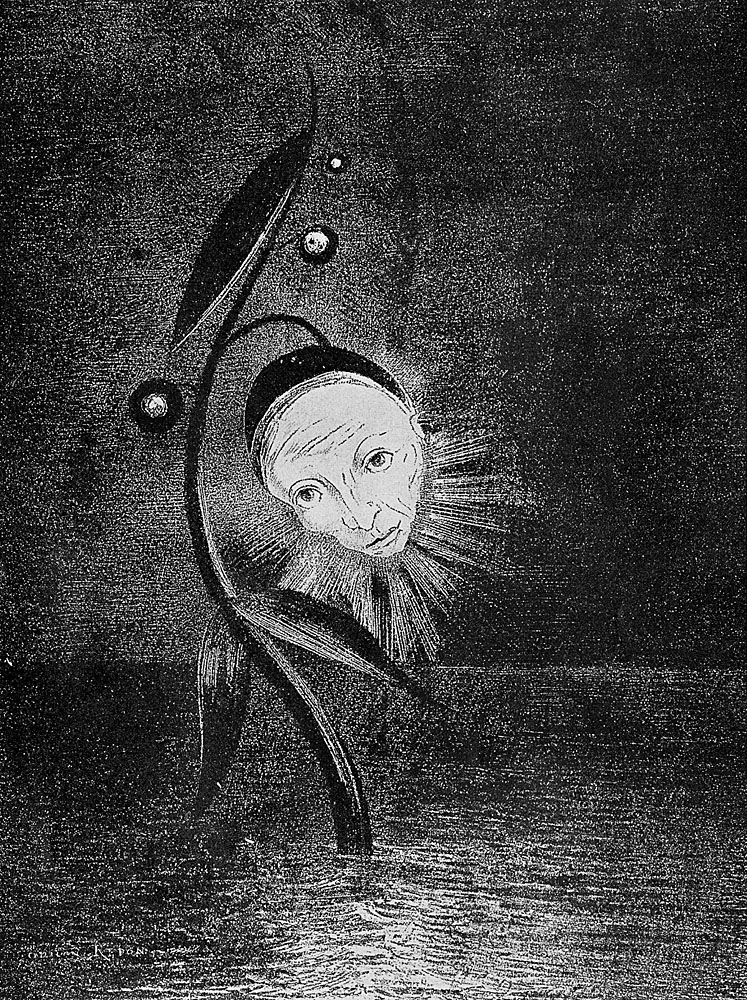

The Eye, Like a Strange Balloon, Mounts Towards Infinity (plate Nº 1), from To Edgar Allan Poe, 1882

Lithograph, 43.8 x 31.1 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

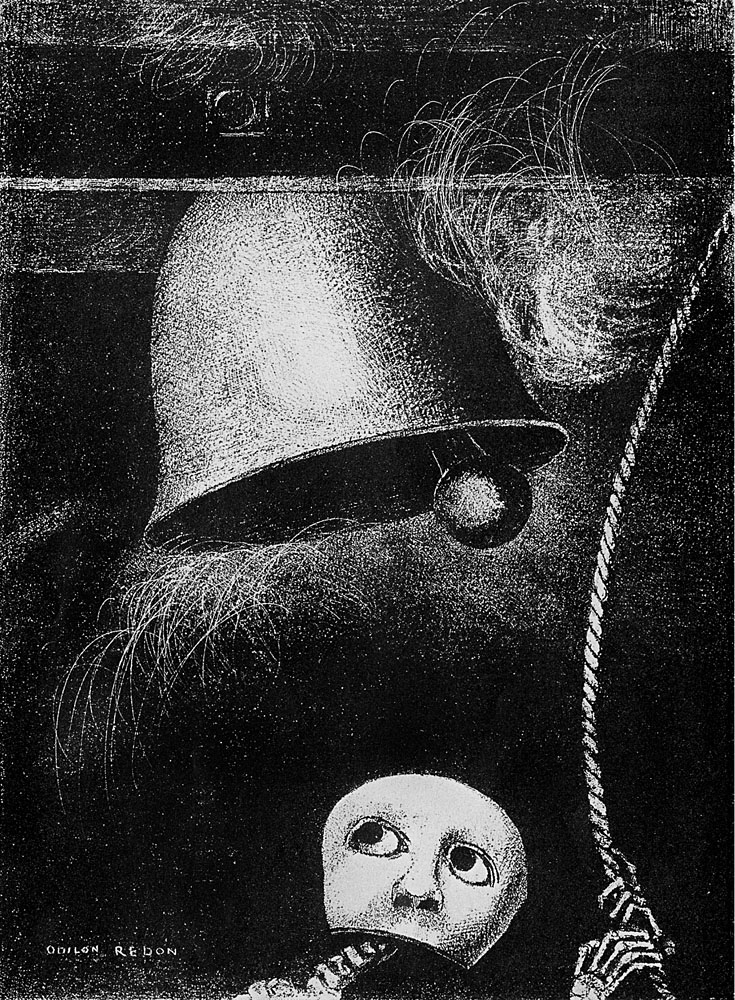

A Mask Sounds the Death Knell (plate Nº 3), from To Edgar Allan Poe, 1882

Lithograph, 43.8 x 31.1 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

On the Horizon the Angel of Certitude, and in the Somber Heaven a Questioning Eye (plate Nº 4), from To Edgar Allan Poe, 1882

Lithograph, 43.8 x 31.1 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

I have kept a tender and heartfelt memory of my master and the ardent hours of study and gentleness passed in his studio (I was fifteen to eighteen years of age); a studio surrounded by an abundance of flowers from a garden outside of the city, and in the silence of solitude, with a large bay window casting light upon the edge of a little forest. Later, after my coming to Paris, when returning to Bordeaux I would always see my beloved master because he loved art, music and beautiful books. He was of the mind that at thirty years of age it was already too late to present your first masterpiece. He was perhaps right about some; he was mistaken about me. I was still finding myself at that age.

I was also friends with Armand Clavaud, a botanist who later worked on the physiology of vegetation. He focused on the infinitely small. Clavaud was extremely gifted. His nature was that of a scientist as well as that of an artist (which is rare), always feeling pity for the revelations of the microscope, always at his herbarium collections that he visited, tended to, and classified endlessly. He still indulged in his passion for reading and literary research, with an enlightened erudition. An extremely wise man, he was always informed of everything. When Flaubert’s first books came to be, he was already referring them to me in discernment.

He made me read Edgar Poe and Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil when they were first published. He professed an almost religious admiration for Spinoza. He had a way of pronouncing his name with sensitivity and with such gentleness that it was possible to hear the emotion in his voice. In the visual arts, Clavaud tasted the serene vision of Greece as much the expressive dream of the Middle Ages. Delacroix, whose paintings still portrayed much unconventionality, was defended by him with vehemence.

To the care of this friend, of a lucid intelligence, I owe the first exercises of my senses and of my taste, the best perhaps, as he envisaged with fear the fruitless efforts I attempted in my art. He preferred me to be occupied by books, and maybe writing, I’m not sure. When he died a few years ago, I suddenly felt like a support was missing. He, who was older than I, and whose education was solidified in the sciences, despite his idealism, was a rock; I listened to him.

I was telling you of my youth. At seventeen years of age, I began architectural studies with little faith and the advice of my parents. I worked daily with a talented architect, as well as some time with Lebas. I did lots of descriptive geometry, the masses stripped down, all the preparation in view of the École des Beaux-Arts where I failed the oral exams. It came to serve me much later; I approached the impossible from the possible with much more ease and I could give visual logic to the imaginary elements that I pictured.

I became who I am alone, as best I could, and because I couldn not find my true calling in the education that I was trying to receive. I did sculpture for a year in Bordeaux. I touched the exquisite material, how soft and supple the clay mud is, trying my hand at making copies of ancient pieces. Here at the École des Beaux-Arts, in the Gérôme studio, I made a great effort to create the shapes; these efforts were in vain, useless, without ulterior motives for me. I was tortured by the teacher. He overworked me, was strict, and his corrections were vehement to the point that when he approached my easel, my peers would wait anxiously.

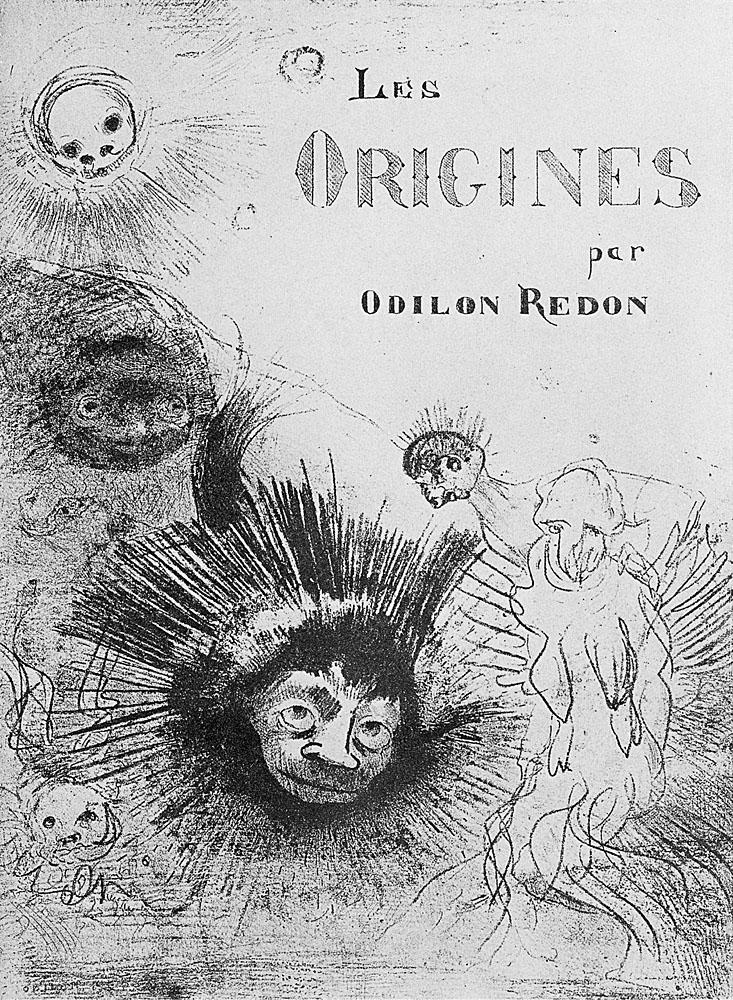

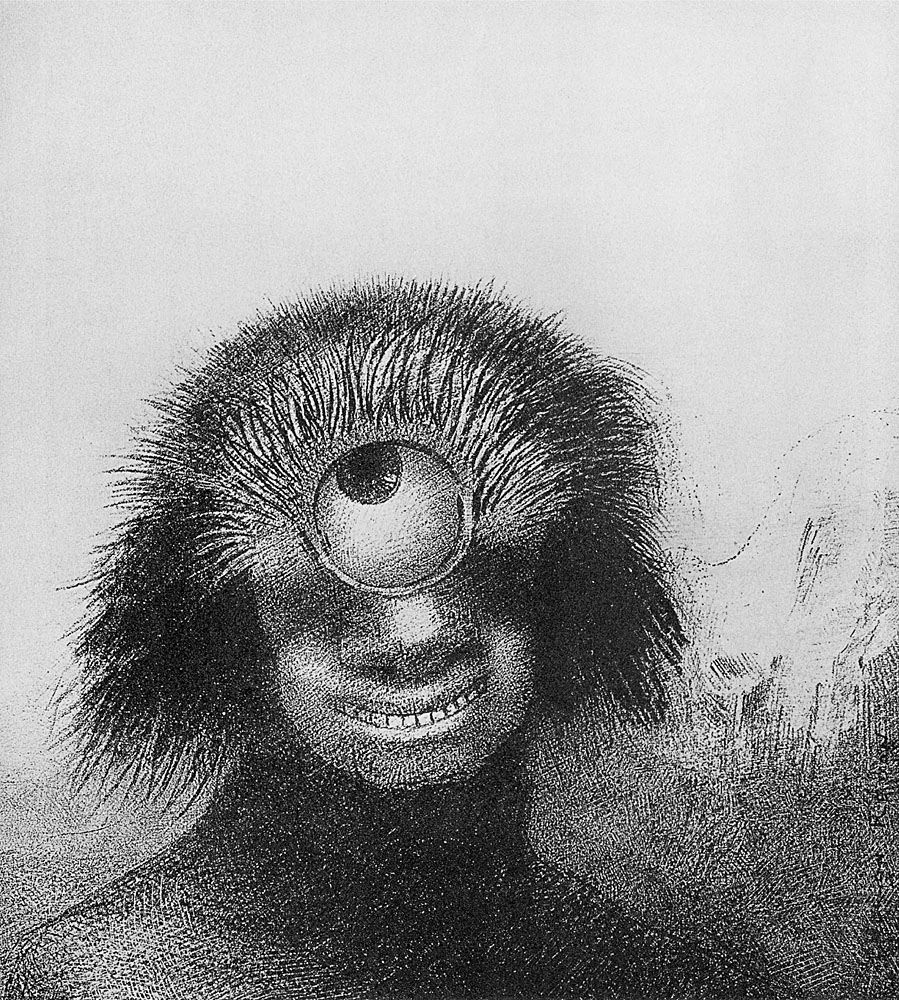

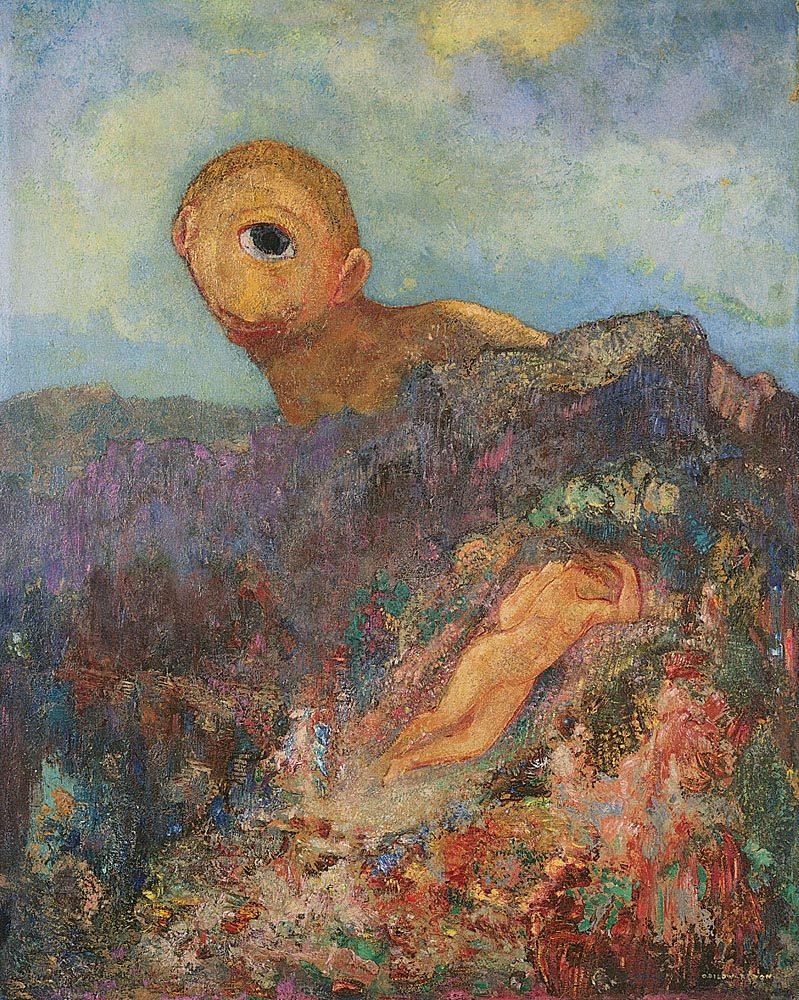

The Misshapen Polyp Floated on the Shores,

a Sort of Smiling and Hideous Cyclops (plate Nº 3), from The Origins, 1883

Lithograph, 21.3 x 19.9 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

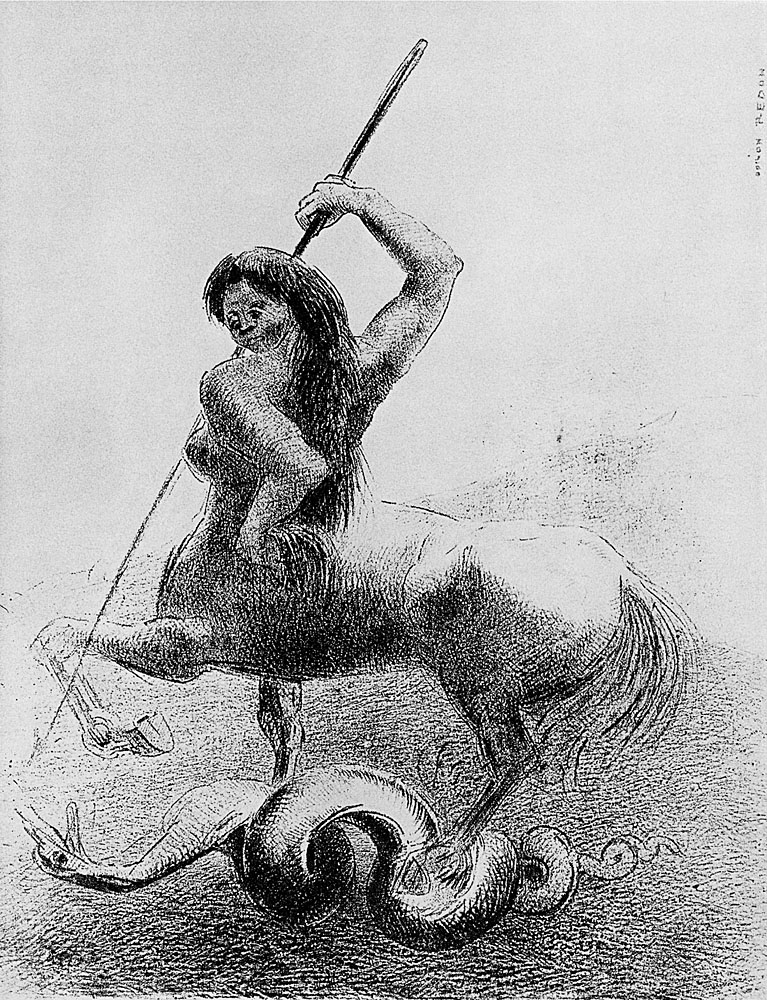

There Were Struggles and Vain Victories (plate Nº 6), from The Origins, 1883

Lithograph, 28.7 x 22.3 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

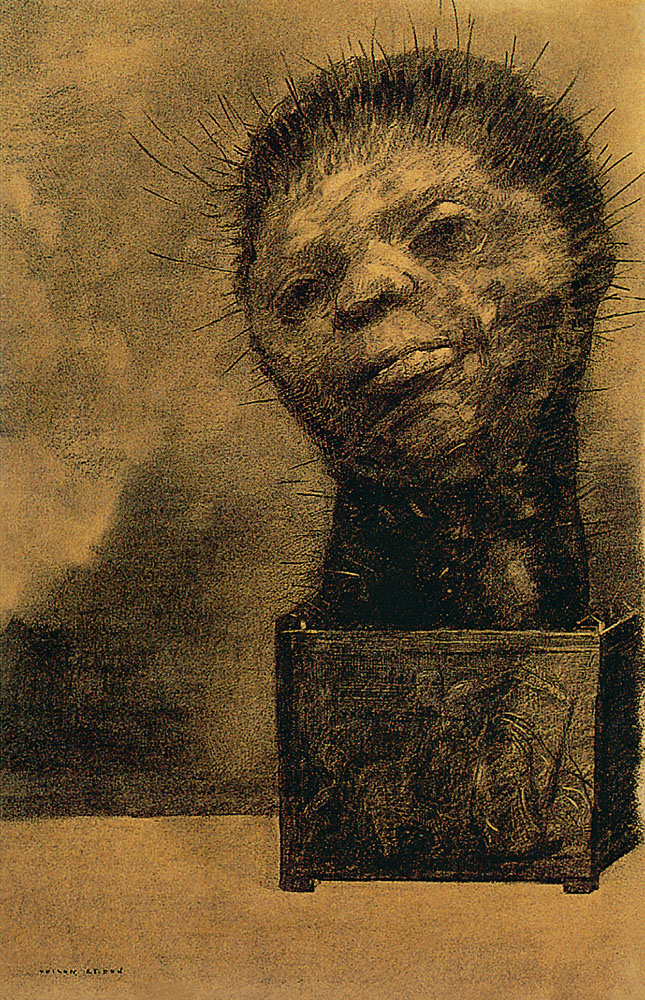

The Marsh Flower, a Sad Human Head (plate Nº 2), from Hommage to Goya, 1885

Lithograph, 27.3 x 20.4 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

He would advise me to capture the contour of a shape I could see, my heart pounding. Under the pretext of simplification (why?) he would make me close my eyes, blocking out all the light and neglecting my vision of material. I was never able to force myself. I can only sense the shadows, the visible depth; each contour was without a doubt an abstraction. This teaching method did not match my character and the teacher received the most obscure of my natural talents, misreading everything. He understood nothing about me. I could see that his willing eyes were closed to what I could see in mine.

Two thousand years of evolution, or the changes in understanding the optical, was little compared to the distance between our contradictory souls. There I was, young, sensitive and fatally from my time, listening to I do not know which rhetoric derived I do not know how from a piece of work from a certain past. This teacher could draw with vigour a stone, a keg, a table, a chair, an inanimate accessory, a rock and all the inorganically natural.

The student could only see the expression, only the triumphant expansion of sentiment from the shapes. There was an impossible link between the two, an impossible union; a submission which would have made the student a saint, although it would have been impossible. Only a few artists have had to suffer what I suffered next, slowly, patiently, and without revolt, to class myself, as well as others, in this common tradition. Those who follow these teachings or in fact these distractions, and send their work to the Salon, had as you would have guessed, the same fate as my work as a student.

I stayed on this dead-end road for too long; the consciousness of a direction had not hit me yet. This distancing made me distinct and independent from others. Now I am extremely happy for it. There is a whole system, a bloodline which now circulates outside of the branches of the official organism. I was brought to isolation where I attempted to make the art I have always made but differently. I understand nothing of what we call “concessions”; we do not do the art that we want to. The artist is from day to day a receptor of their surroundings; he receives from the outside sensations which transform him fatally, inexorably and persistently according to him alone. There is only really the creation of art once we have something to say. I would even say that the seasons affect the artist, they trigger or dull his dreams; the effort, and those attempts outside of these influences that experience brings along are beneficial to him if he places himself above them.

I think I worried about the direction of my talents; I consciously went looking for myself in the wakening and development of my own creations, with a desire to present them perfect; that is to say, complete, autonomous, as they should have been by themselves. But did I have the temperament of a painter or a draughtsman? What would it do to look for it now? There is but a slight distinction in these two types of instruction. However, we can distinguish them through analysis.

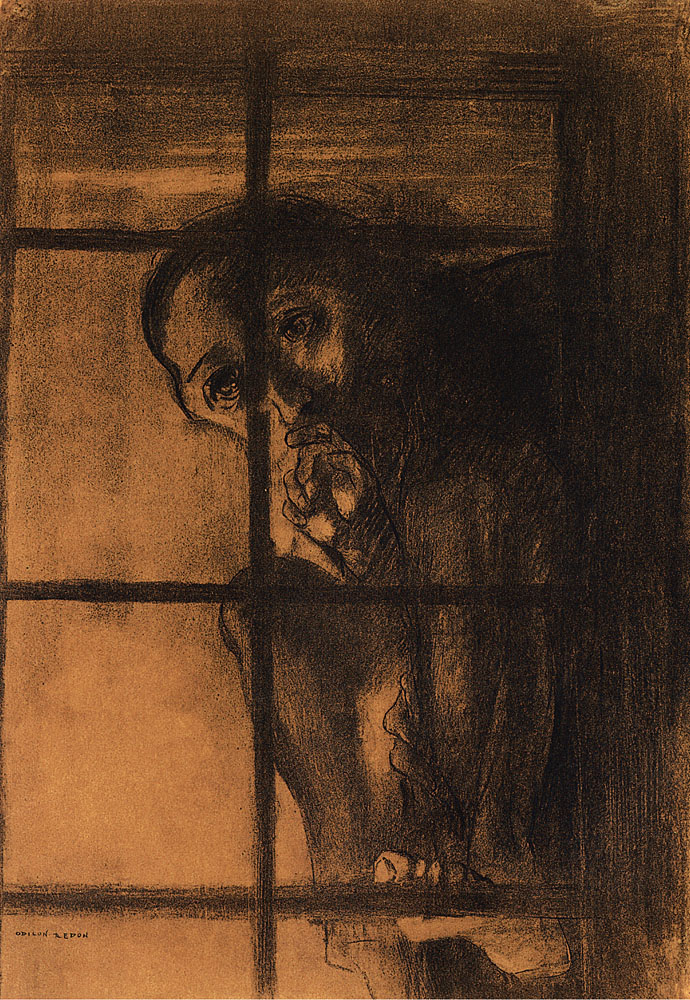

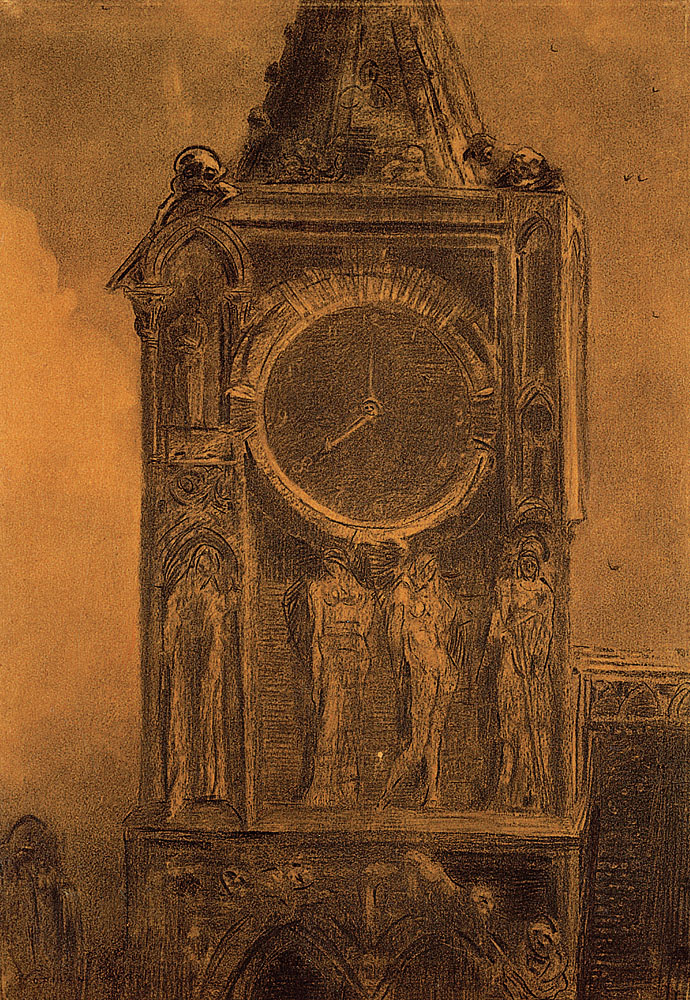

Christ, 1887

Lithograph on ivory China paper laid down on white wove paper,

33 x 27 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

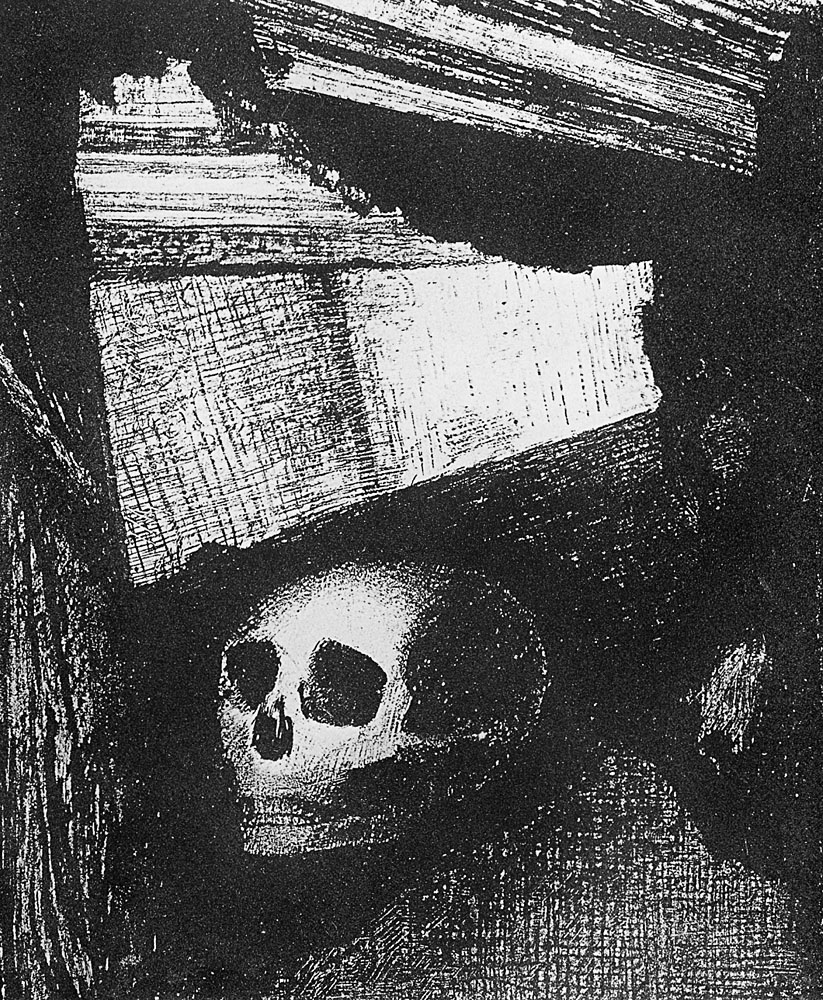

The Wall of His Room Was Opening Up and from the Crack a Death’s-Head Was Projected, Illustrations for The Juror by Edmond Picard, 1887

Lithograph on ivory China paper, laid down on white wove paper, 18 x 15 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

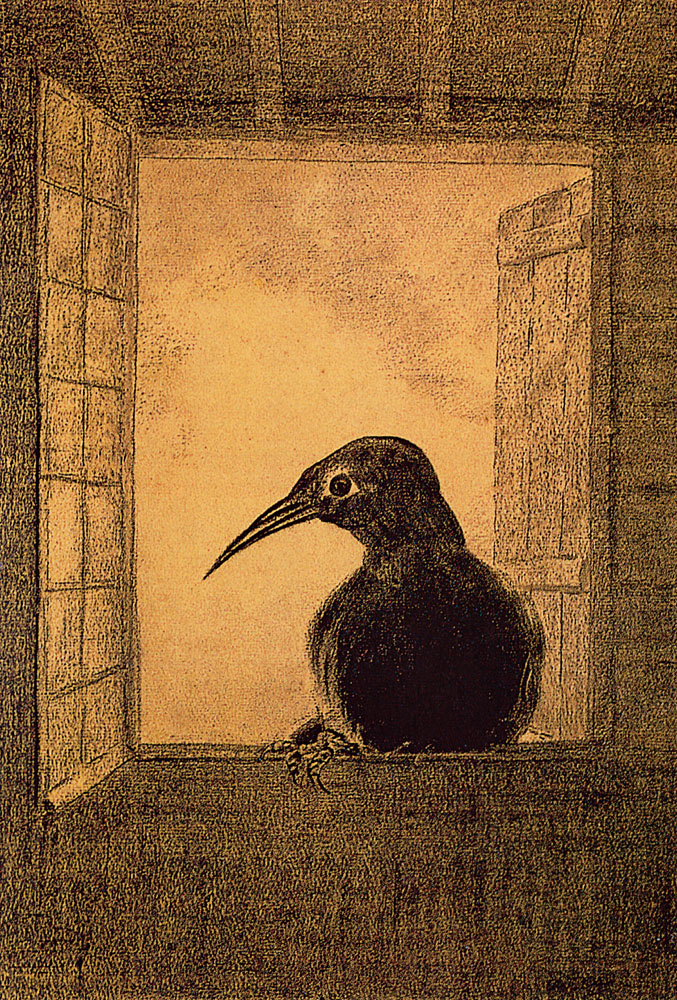

And a Large Bird, Descending from the Sky, Hurls Itself Against the Topmost Point of Her Hair (plate Nº 3), from The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Gustave Flaubert, 1888

Lithograph on China paper, 19.1 x 16.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

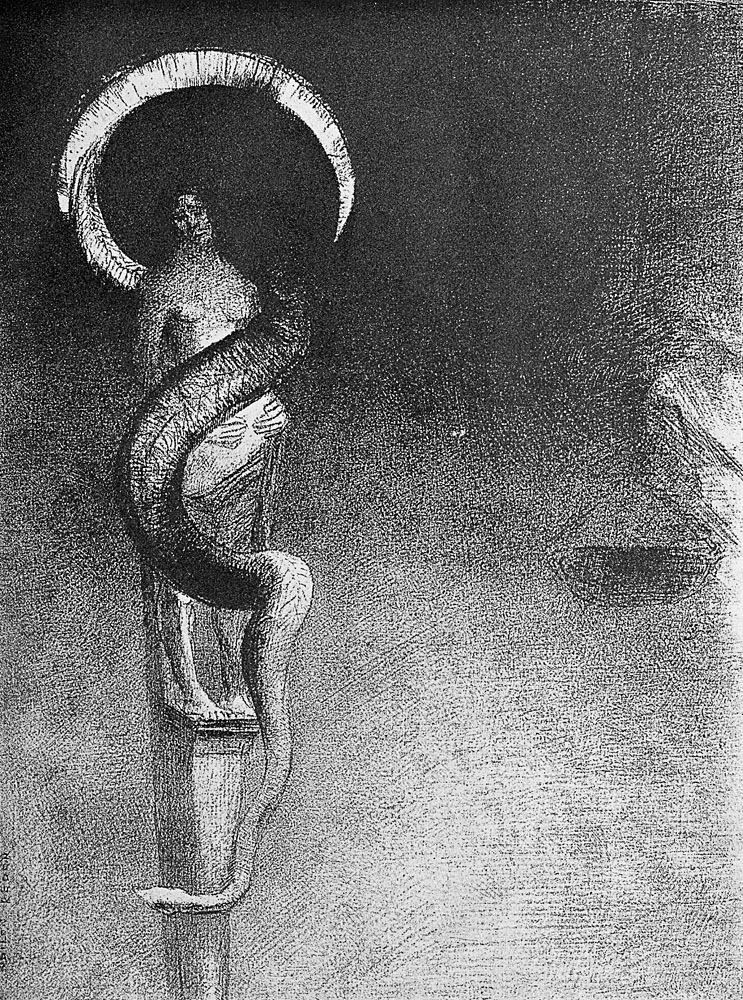

Serpent-Halo (Serpent-Auréole), 1890

Lithograph on ivory China paper laid down on ivory wove paper, 30.2 x 22.2 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

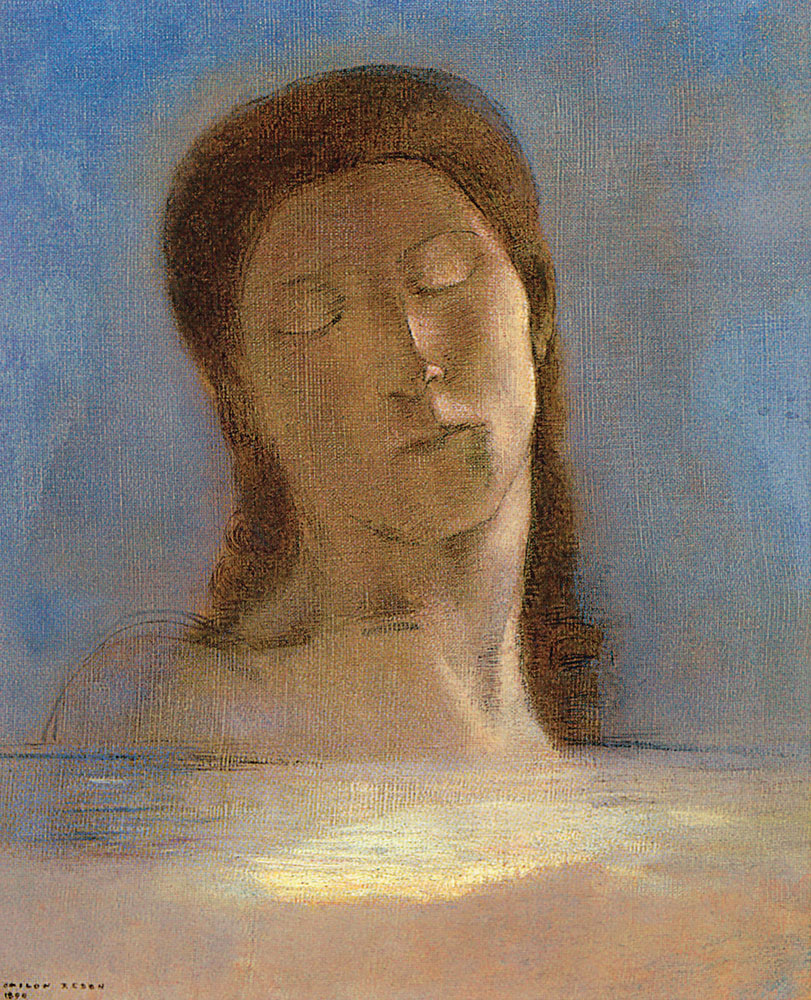

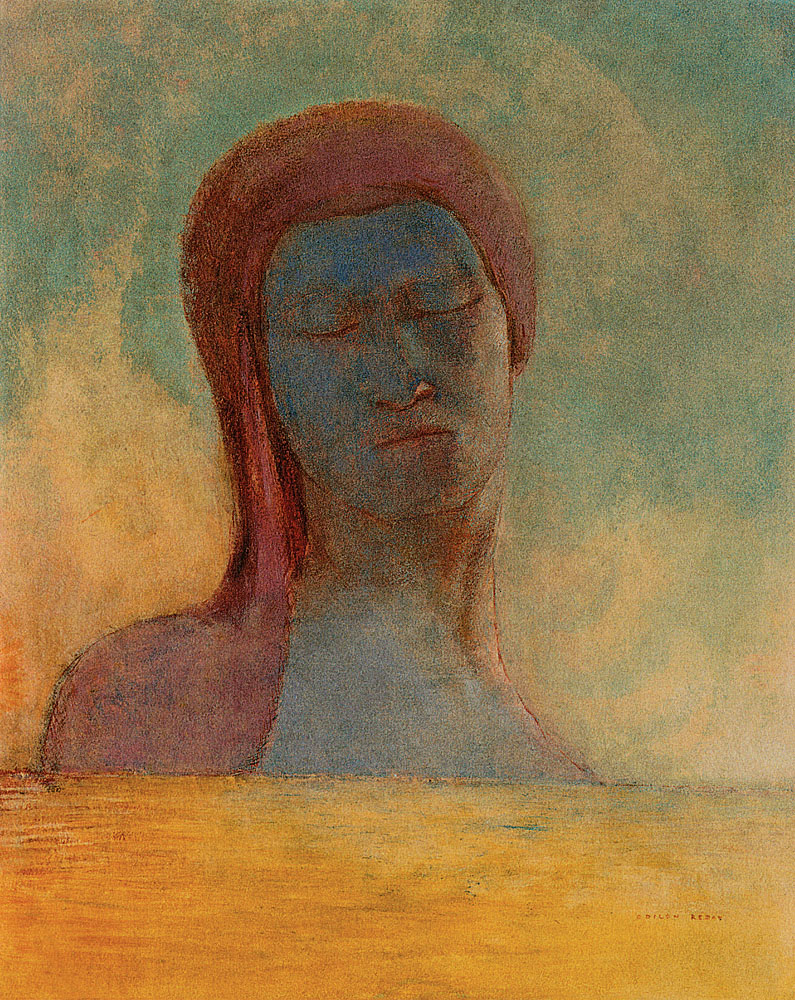

Closed Eyes, c. 1890-1899

Oil on cardboard (with a gold background), 30.5 x 28.5 cm. Private collection

The practice of drawing came to me much later, through determination, slowly and almost painfully. What I mean by drawing here is the ability to objectively express the representation of things or people according to their character. I also maintained it as an exercise and because it is necessary to grow in the most essential element of the art we produce; but I also observed the direction of the line – even though I would give in to the charm of the chiaroscuro. I would also make the effort to paint all the details, and a small piece in relief, a fragmented detail. Studying interested me the most but its usefulness concerned me very little.

These fragments have since served me well to reconstitute works and even to imagine some. That is the mysterious journey from the effort and the finished product towards achieving your destiny. It is sometimes decisive and determined in others, it was often troubled and worrisome in me, but I never let the end point out of sight and resisted the pull of tendencies which seemed to come from other art. I was a faithful listener at concerts; I always had a good book in my hand.

My aptitude for contemplation rendered my efforts towards the optical painful. At what moment did I become the object, that is to say, the looker of things, aware of the nature in oneself, to achieve my goals and adapt to the visible shapes? This was around 1865. We were in the throes of avant-garde naturalism; Courbet was at the heart of spreading the art of true painting. This unknown classic was fermenting the youth in the art of painting. Millet was also shaking things up in high society, drawing peasants in clogs and the rustic quality of their simple life. I had a friend who introduced me to all the sensualities of the palette, in theory and in practice. He was the polar opposite to me and from there our discussions never ended. We would do landscapes together and I would endeavour to capture the mood of reality. At this moment in time I had passed my exams which were inevitably on painting.

What rendered it so difficult for me to create in the beginning and why did I do it so late? Was it an optical which did not agree with my talents? A sort of conflict between the heart and the mind? I do not know.

In the beginning I was always leaning towards perfection, and if you can believe it, perfection in shapes. But let me tell you now that no visual shape, objectively speaking, under the laws of shadow and light, and deemed the conventional “model”, would be found in my work. More so because I was often tempted in the beginning and because you need to know as much as possible to reproduce the visible objects according to this old optical artistic style. I merely did these as exercises. But I tell you today, in all my conscious maturity, and I emphasise, all my art is limited only to the resources of chiaroscuro and it owes a lot to the effects of the abstract line, this agent of a profound source, directly affecting the spirit. Suggestive art can provide nothing without running back to the mysterious games of shadows and the rhythm of the lines created in your mind. Oh! Was there ever such a great result as in the work of Vinci? He owes his mystery and the fertility of the fascinations that he provokes in our spirits. They are the roots of words of his tongue. It is also by perfection, excellence, reason, and docile submission to the natural laws that this admirable and sovereign genius dominates all the art forms; it dominates them to their very essence. “Nature is full of infinite reasons that are never experienced”, he wrote. It was for him, like for all masters, the evident necessity and the axiom. Which painter would think otherwise?

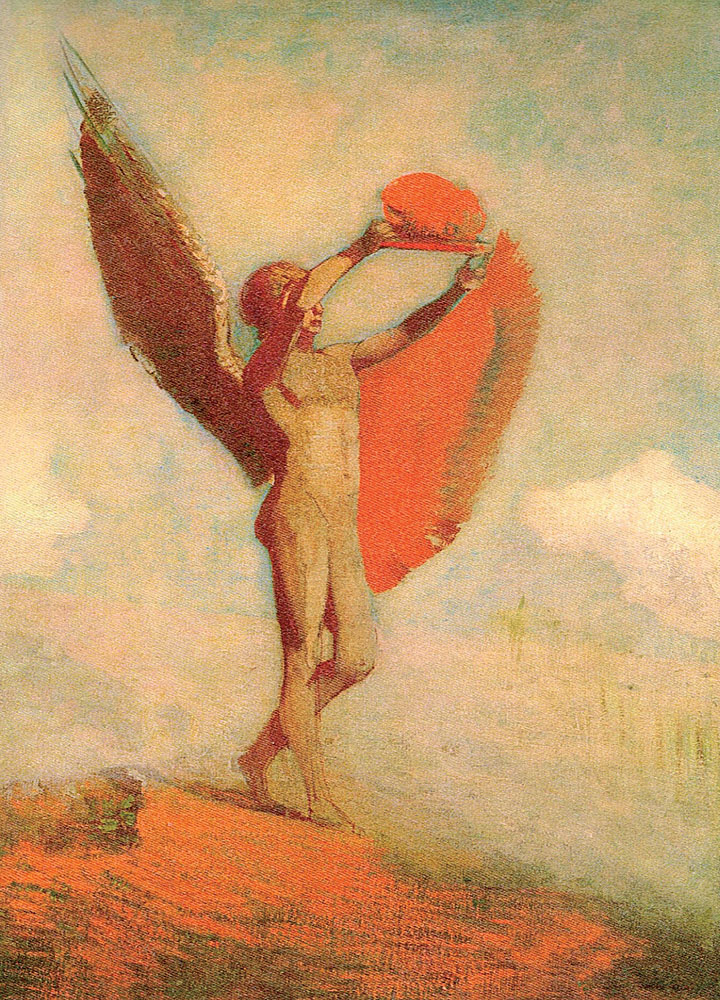

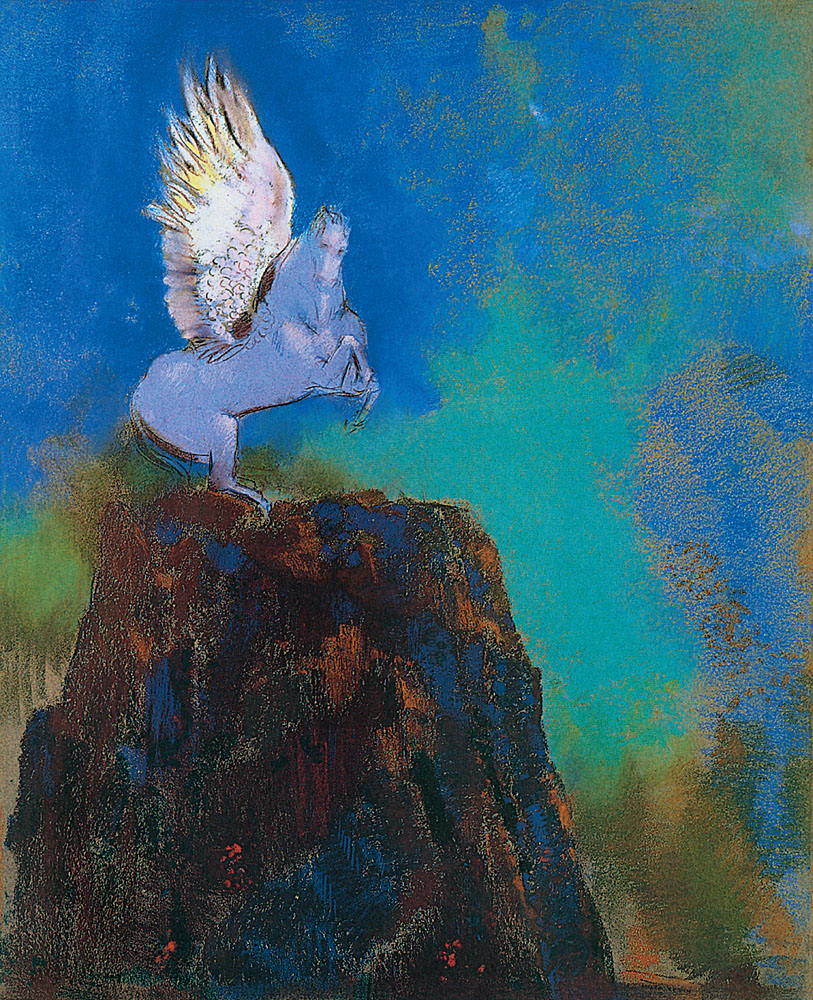

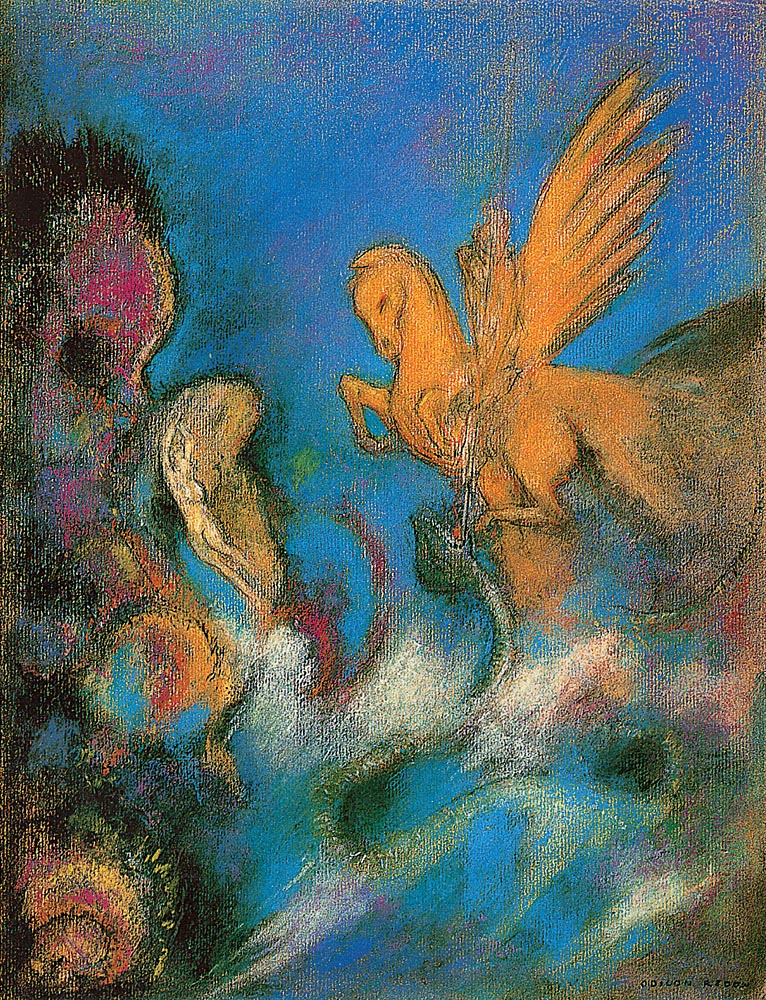

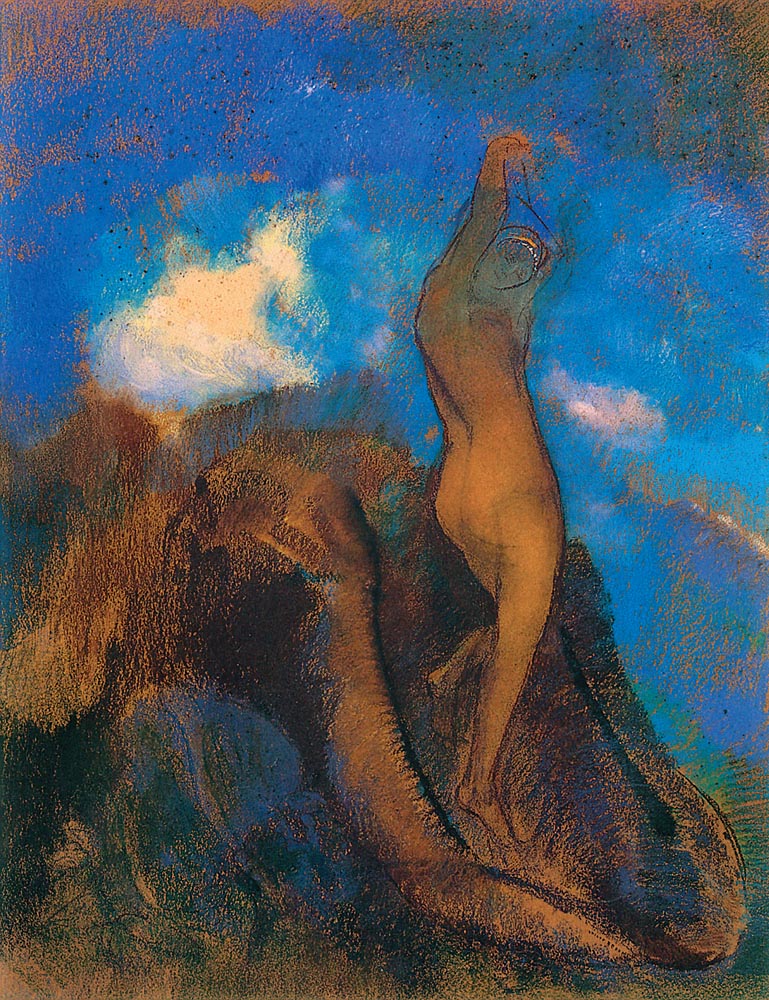

Icarus or The Offering, c. 1890

Oil on paper hung on canvas, 52.1 x 38.1 cm. Pola Museum of Art, Hakone

The Winged Man or The Fallen Angel, 1890-1895

Oil on cardboard, 24 x 33.5 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, Bordeaux

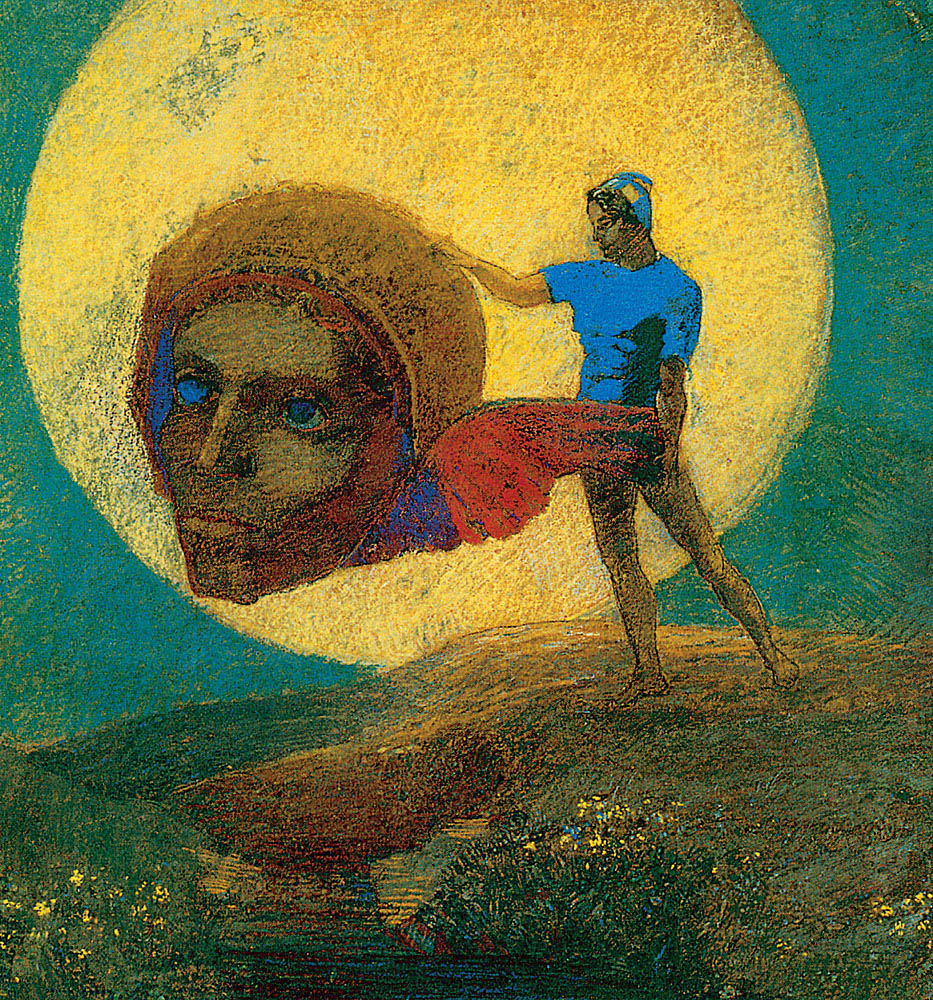

The Fall of Icarus, date unknown

Pastel, 48.3 x 45.7 cm. The Rothschild Art Foundation, United States

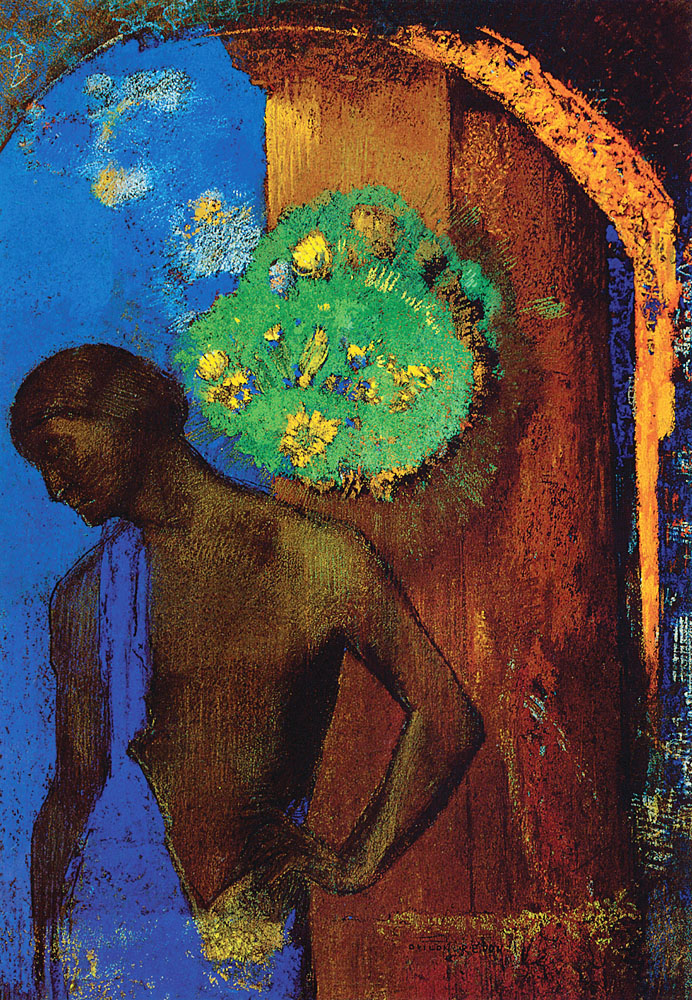

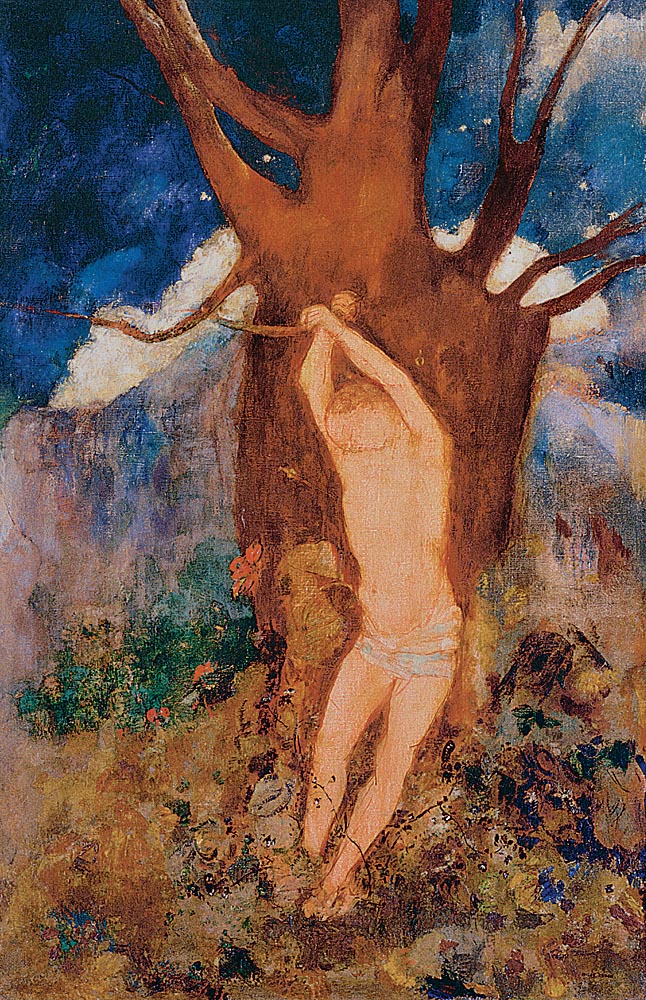

The Druidess, c. 1893

Charcoal embellished with pastel, 64.4 x 39.4 cm

The Ian Woodner Family Collection, New York

It is also nature that pushes us to obey the talents she has given us. Mine have lead me to dream; imagination has made me suffer but, pen in hand, it has also surprised me; and I ploughed on through and managed them, these surprises, according to the laws of the organism of art that I know, that I feel, with the only goal of obtaining from the spectator, by a subtle attraction, all evocation, all attraction of the uncertain on the confines of thought.

I said nothing either of what was largely felt by Albrecht Dürer in his Melancholy engraving. We would think it incoherent. No, it is written according to the singular line and its strong powers.

Suggestive art is a manner in which to relieve one’s self of their dreams and where thoughts also end up. Decadent or not, that is how it is. Let’s say instead that it is growth, an evolution of art for the supreme development of our own lives, its expansion, its highest pressure point and the moral maintenance by necessary exhalation.

This suggestive art is submerged in the exciting art of music, freely, radiantly; but it is also mine by a combination of different elements brought together, of shapes transposed or transformed, with no correlation to the contingencies but still maintaining logic. All the errors in the criticism made against me in the beginning were because they did not see that there was nothing to define, nothing to understand, nothing to limit, nothing to clarify because all that is honestly and submissively new, like otherworldly beauty, holds its meaning in itself.

The designation of a title put to my drawings is sometimes too much. The title is only justifiable when it is vague, undetermined or even confusingly, pointing towards the ambiguous. My drawings inspire and do not define themselves. They do not determine anything. They place us, as does music, in the world of the ambiguous and the undetermined.

They are therefore, without other explanation which could be any more precise, the repercussion of a human expression, placed, fantasy permitting, in an arabesque game, where I believe that the action derived from the spirit of the spectator will incite the fictions whose meanings will be big or small, depending on the sensitivity and the imaginative aptitude to make everything either bigger or smaller.

There is a method of drawing that the imagination has liberated from the embarrassing attention paid to real details, which only makes use of the representation of imagined objects. I created some fantasies with the stem of a flower, or the human face, or even with the elements derived from the skeletal structure, designed, constructed and built as they were meant to be.

This is because they are an organism. Each time that the human body does not give the illusion that it will, for example, walk out of its frame, act, or think, the truly modern drawing has not been achieved. You cannot take away the merit of giving the illusion of life to my most unrealistic of creatures. All my originality therefore lies in giving living human traits to the most incredible beings according to the laws of the credible, putting as much of the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible as possible.

But on the other hand, my most fertile system, the most necessary to my growth, was, as I often said, by directly copy reality whilst attentively reproducing objects from the external nature that have a bit more to them, something more individual or accidental.

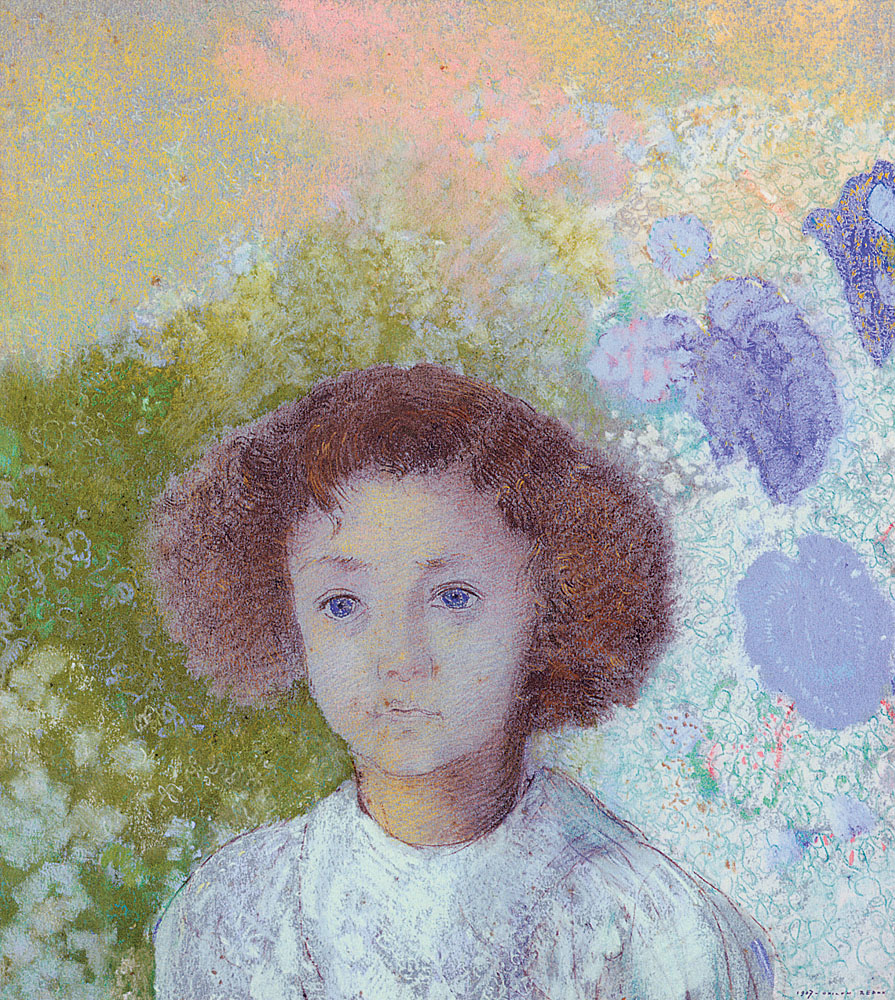

My Child; Portrait of Redon’s Son, Arï, 1893

Lithograph on ivory China paper laid down on heavy ivory wove paper, 22.8 x 21.3 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

Brunhild, Twilight of the Gods, 1894

Lithograph, 38 x 29.2 cm. Musée départemental Stéphane Mallarmé, Vulaines-sur-Seine

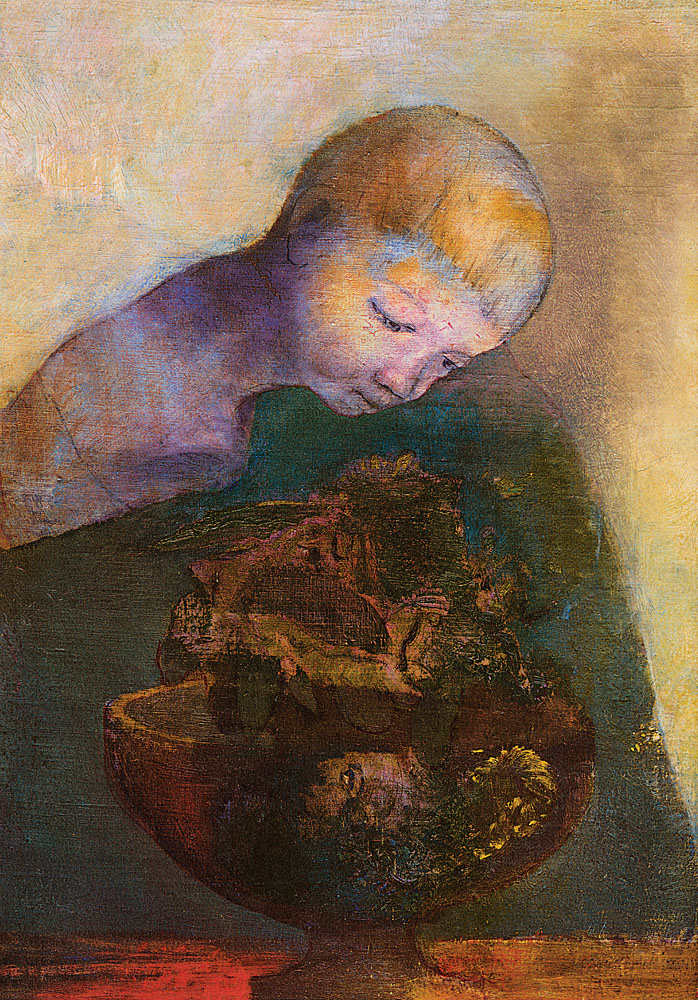

The Cup of Cognition (The Children’s Cup), 1894

Oil on canvas on cardboard, 49 x 34.3 cm. Michael Altman Fine Art and Advisory Services, LLC, New York

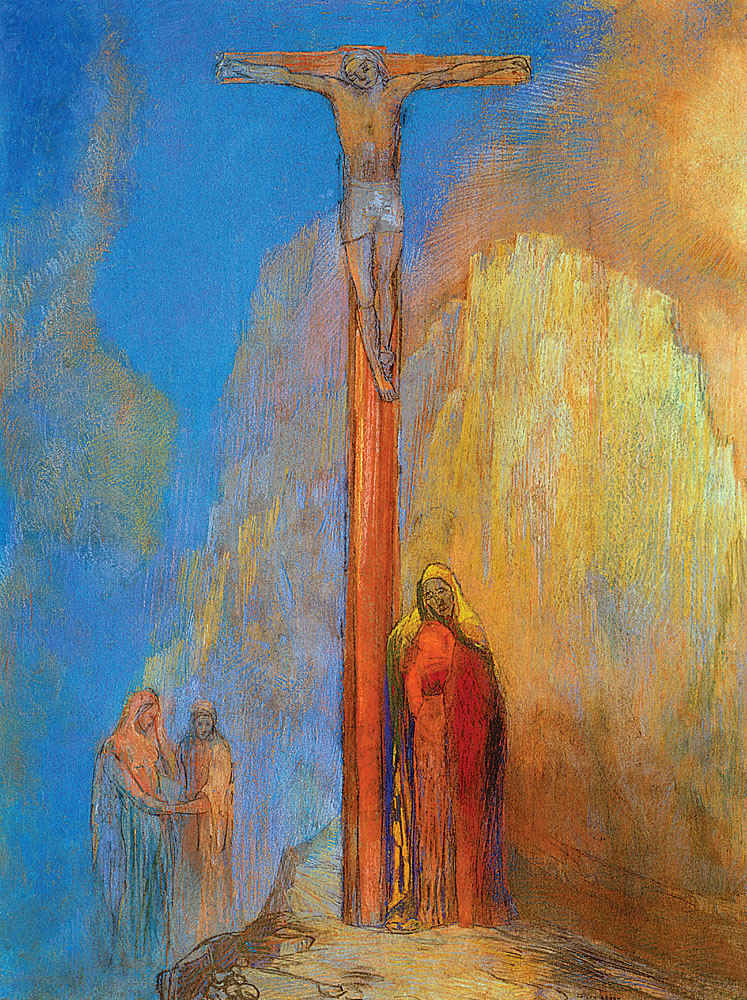

Christ on the Cross, c. 1895

Pastel and graphite on cardboard

Foundation E. G. Bührle Collection, Zurich

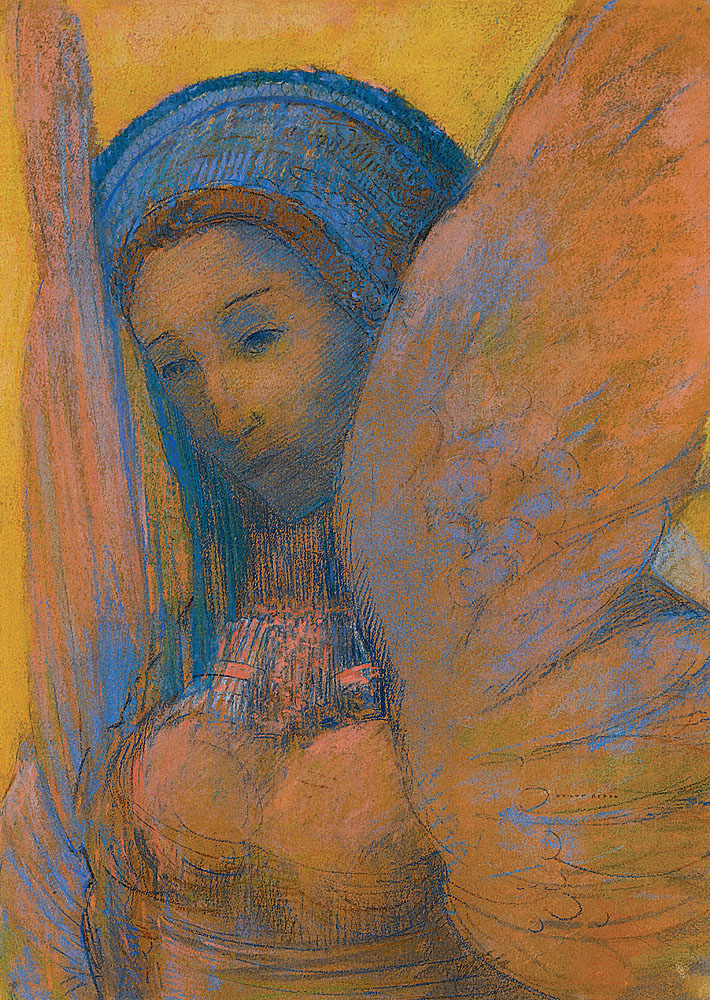

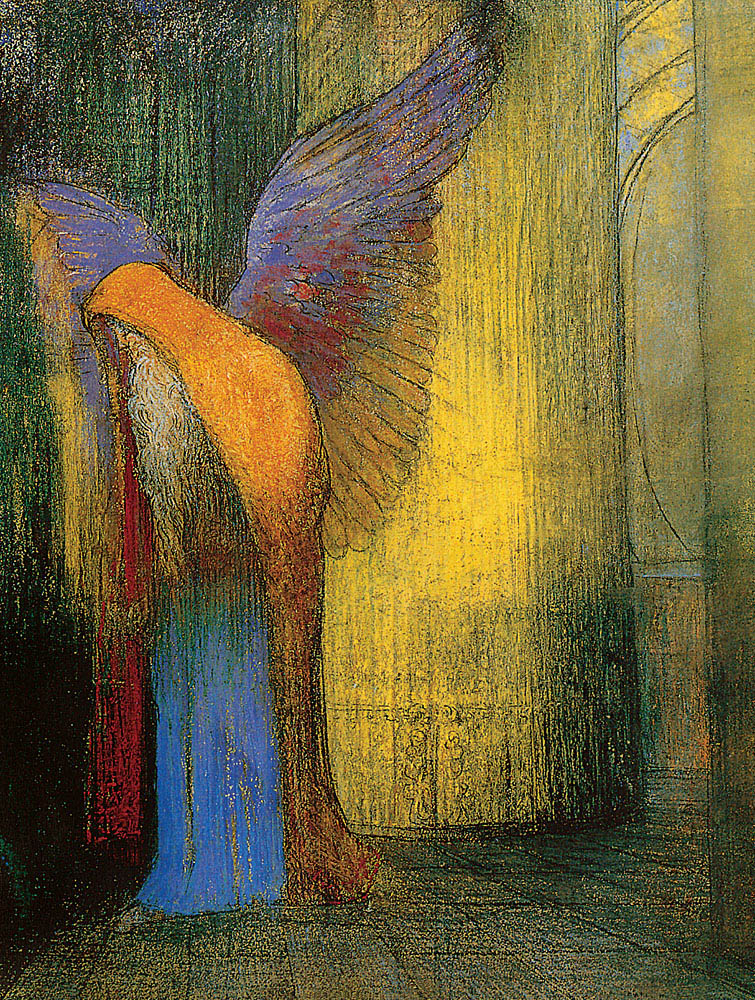

Winged Old Man with a Long White Beard, c. 1895

Pastel on grey-beige paper, 56.9 x 39.7 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

1867 – 1978: Ideas about Art

The official juries of painting unofficially recommend that you present your most important pieces of work at the Salon. What do they mean by that word “important”? A work of art is important due to its dimensions, its execution, the choice of subject, the sentiment, or the thought. The principle of the amount counts for nothing with regards to judgements based on beauty. Each work which is considered worthy by a single judge should be admitted. This is the only manner in which the Salon will incorporate some diversity.

From the walls of our cathedrals, just as from those made of marble in Greece or Egypt, everywhere where mankind, civilised or wild has lived, through art we relive the most moral aspects of our lives; we relive spontaneously and radiantly and it is a prodigal resurrection. In short you must suffer and art must console; it is a consolation. And this oblivion that we find in our happy research is what gives us our riches, our nobility and our pride.

My life did not break away from certain customary habits; the rare outings I did make were not enough to fully question the laws of my development. Our days alternated between the city and the countryside; the second of which always made me relax. As well as giving me physical strength it also gave way to new artistic ideas; the first, specifically Paris, provided the intellectual springboard all artists must continuously maintain. It also gave me awareness of the direction that all the effort of the hours of study and my youth, as much as it is good to abandon when we believe, it is also good to know what is good to love and where the spirit thrives.

After all my efforts in various directions, I did not really like my paintings or art until I felt, not what I would call virtue, but that my own inventions gave me in the form of surprises or unexpected outcomes, as though the results had surpassed my expectations. I read somewhere that the power to include more meaning in a work than that initially desired, and to in some way surpass your own desire by an unexpected result, is accorded only to those sincere beings of complete honesty, those who carry in their soul more than just their art. I thought it too: they need to worry about the truth, maybe the gift of taking pity or suffering.

The study of a painting does not offer resources as sturdy as do fragmented pieces established without order or without thinking of the canvas. It is not the study we will consult in the studio when we look for the support of secure information! On the contrary, the naive study, that which we do when we forget what we know and want to approach something we see calmly, stays as a reliable document, fertile, inexhaustible in resources, from which we will not tire. “Next to an uncertainty, put a certainty” said Corot to me. He made me look at studies prepared with feathers or leaves, with an abundance of visible tufts, drawn as well as engraved. “Each year go and paint in the same place; paint the same tree” he told me.

Writing and being published is the most noble and most delicate work a man can do because others are involved: acting on the mind of another; what a task, what responsibility before the truth and before one’s self. Writing is the biggest art. It traverses time and space, its superiority manifests itself over music and its language transforms and leaves behind a work of the past.

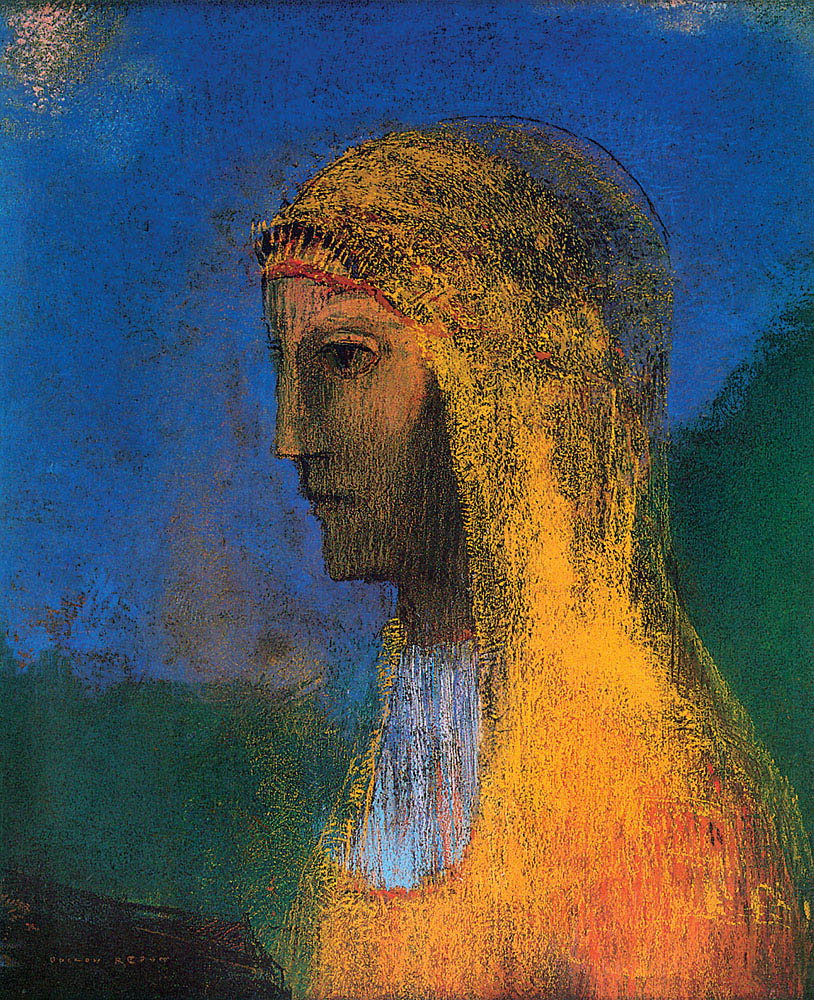

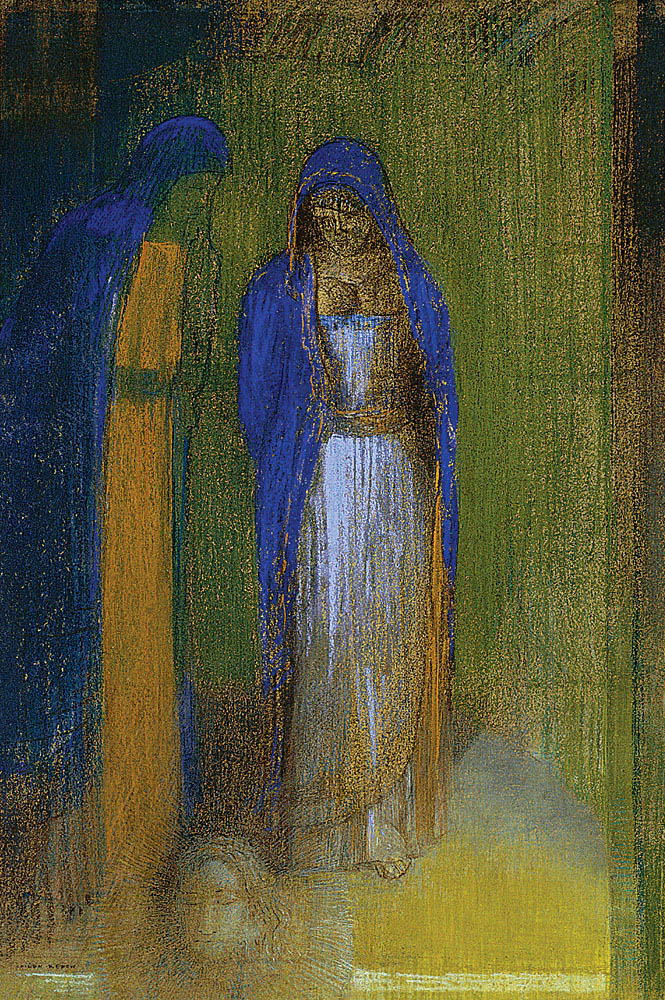

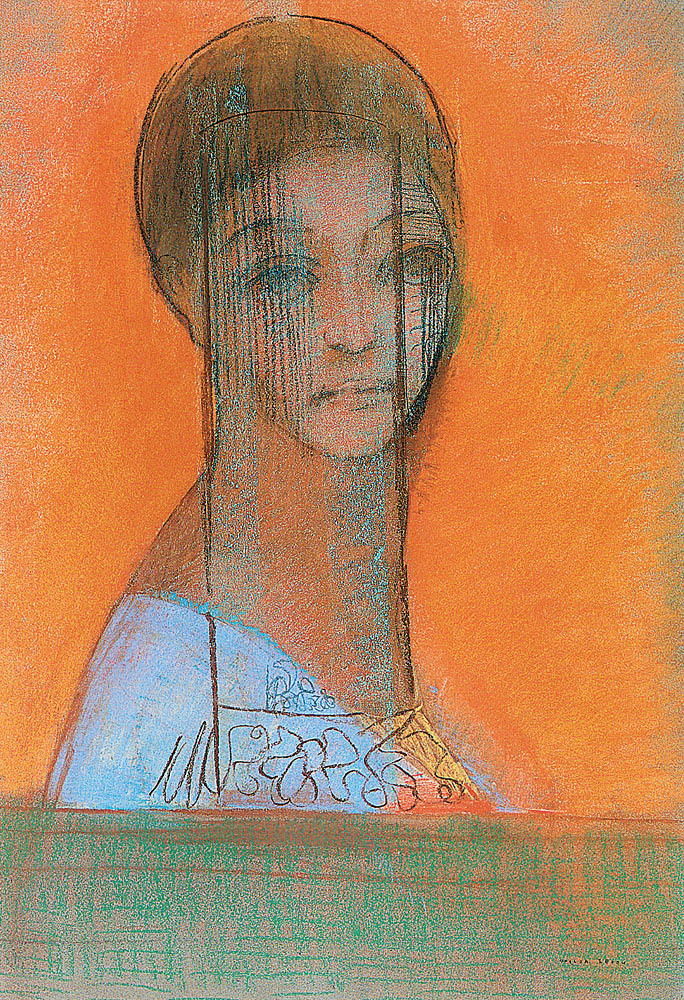

Veiled Woman, c. 1895-1900

Pastel and chalk on blue paper, 47.5 x 32 cm

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Anthony: “What is the object of all this?” The Devil: “There is no object!” (plate Nº 18), from The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Gustave Flaubert, 1896

Lithograph, 31.1 x 25.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

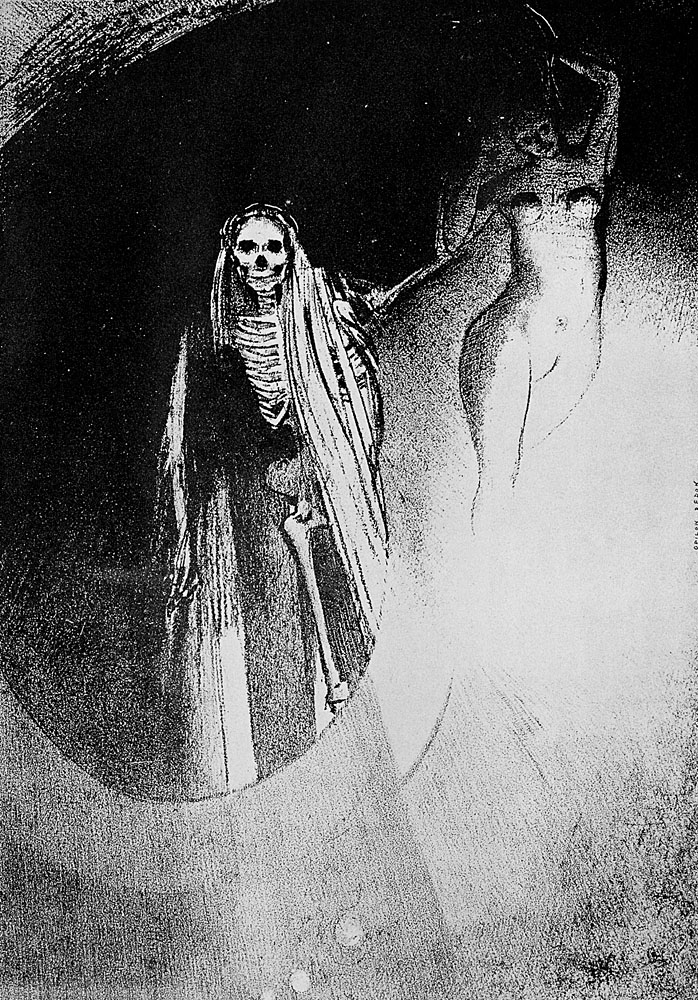

Death “It Is I Who Make You Serious; Let Us Embrace Each Other” (plate Nº 20), from The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Gustave Flaubert, 1896

Lithograph, 30.3 x 21.5 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

What distinguishes the artist from the amateur is only the pain experienced. The amateur only looks for pleasure in their art. The taste of art is nothing compared to the pains of the heart. In each artist there is a man, a man that needs to be cared for and cultivated. Perhaps man is the simple process for the work of an artist. Art is powerless to return the qualities of these situations and all the delicacy of their influences.

The artist should not, under sacred authority, think himself better than others. The sense of creation is something but it is not everything. A mediocre man or even a man completely hopeless at sensing beauty could put forward some noble or superior points. Of course you have to bless the heavens because we are living in a world where Beethoven and the God of art have infiltrated our lives and we must pride ourselves on understanding it; however I find it profoundly selfish and second-rate the suffering of persons who think their worries are more important.

What remains, and what should be known about each century, are the masterpieces. They are of a complete expression, unique and true. In the previous centuries, what is most essential and characteristic in the work of the human mind is best described in secondary documents and, closer to the people, in the real craftsmanship of all things.

In all moral situations conductive to the production of art or thought, there is nothing more fruitful than great patriotic suffering. In fact, these supreme disputes are born of populations so diverse in their aspirations and tendencies, that it creates in the individual a high level of apprehension. When this is solved by the use of weapons, that is to say with the risk of deaths, each one of us has in a way made a useful sacrifice to our moral evolution. This anxiety bypasses the high confusion of our personal preoccupations and guides us towards a better ending. It raises our heart, clears our conscience, inspires passion and develops our intellect; the words humanity, country, honour and duty take on their true meanings once again. Eventually, it distances the mind from the facts to rise to more general and abstract notions. In support of these reflections, we can see that the most important artistic movements and developments have closely followed our victories and disasters, and in the intimacy of our social evolution, in the heart of our happy or unhappy country, the era of progress and faith has been inextricably linked to our supreme revolutions.

Reading is a cultural resource for the mind: it enables a calm and silent aggregation with the Holy Spirit, the great man who bequeathed us his thoughts; but reading alone is not enough to shape a complete mind, able to function healthily and with strength. The eye is indispensable to the absorption of the elements which feed it, as well as to our soul, and whoever, in a certain measure has the faculty of sight, but is incapable of seeing justice, of seeing the truth, will have an incomplete intelligence. To see is to spontaneously be able to identify the relationships between things.

And He Had in His Right Hand Seven Stars; and Out of His Mouth Went a Sharp Two-Edge Sword (plate Nº 1), extract from The Apocalypse of Saint John, published by Ambroise Vollard, 1899

Lithograph, 29.2 x 20.9 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

A Woman Clothed with the Sun (plate Nº 6), extract from The Apocalypse of Saint John, published by Ambroise Vollard, 1899

Lithograph, 23 x 28.6 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

I Saw an Angel Come Down From Heaven, Having the Key of the Bottomless Pit and a Great Chain in His Hand (plate Nº 8), extract from The Apocalypse of Saint John, published by Ambroise Vollard, 1899

Lithograph, 30.4 x 23.2 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

I am asked about the certainty in my art. You have to have the good sense to confess, without argument and without deceiving anyone, that you are certain only of the art that you have created. All other art lives in the unknown, in a mystery where its potentiality could blossom. My beliefs appear inscribed in those works resulting from my personal effort across all the pedagogical disciplines; they are simply, official or not, of the time I have lived in.

Painters, go see the sea. You will see marvels of colour and light, the sky sparkling. You will feel the poetry in the sand, the charm in the air, the imperceptible subtlety. You will return stronger and saturated with inspiration.

Without being, or wanting to be from any sect or school, specifically with regards to art, there is a loyalty to the spirit which has to applaud beauty everywhere and anywhere it can be found. This imposes on those who understand it the desire to communicate it, to explain it.

I am not intransigent; I will never acclaim a school which, although advocated in good faith, restricts itself in pure reality, without accounting for the past. To see and to see well will always be the first precursor to the art of painting, this is true for every century. But it is also important to know the nature of the eye that is watching, to look for the cause of feelings experienced by the artist and communicated to the amateur – even if the artist himself is one – to see, in one word, if his gift is good-natured, and well structured; and that is not the end of the analysts and the critics jobs. That it is important to put the work where it belongs, in the temple that we raise in spirit to beauty.

Good sense is the aptitude to judge well, even without any culture and in the order of truth, a little down to earth. This aptitude primarily serves men who are only aware of the most immediate realities of life. It is essential to those who create art; its absence can sterilise even the best gifted minds. However, we may also lack completely and ridiculously any practical senses and still be a genius. The artist always has an eye, an eye that sees.

Photography used only in the reproduction of paintings or of bas-reliefs seems to me to be in its true role, for it is an art that it is seconding and helping, without being misleading. Imagine the museums replicating this! The mind refuses to calculate the sudden importance painting thus placed on the same level as literary power (the power of multiplication) and of its new ensured safety of the time.

I can tell now that I am older and more talented, those who only have their style, their weak methods, their sterile fixations, depravity and the vain desire to appear skilful. They misunderstand the studies of Corot which are masterpieces of clumsiness: the mind and the eye control everything, the hand is a slave under observation. Corot is the ingenious and sincere initiator of this method of painting in the same style of former painters when they were studying. Landscapes done like this interest and delight me. It is hideous to see a plaster moulded on nature. For landscapes it is the same cynicism: trees, forests, streams, prairies, skies, and clouds. We could do nothing worse to disrupt the view, corrupt the students, rip out the seeds of art in the face of the youth; it is not superior; its goal is different; it is something else. Despite Rembrandt’s male energy, he has kept the sensitivity which leads him on the path of his heart. He has searched for it everywhere.

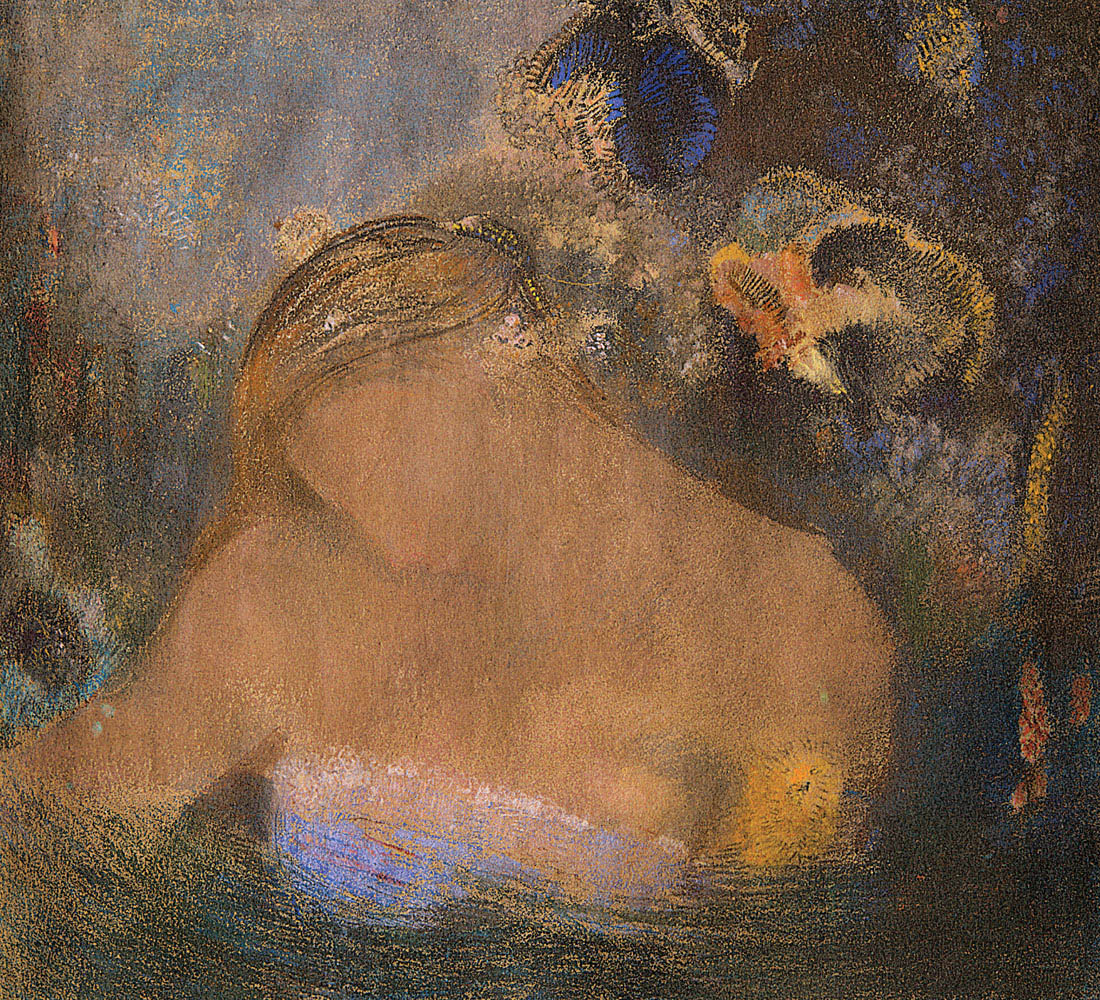

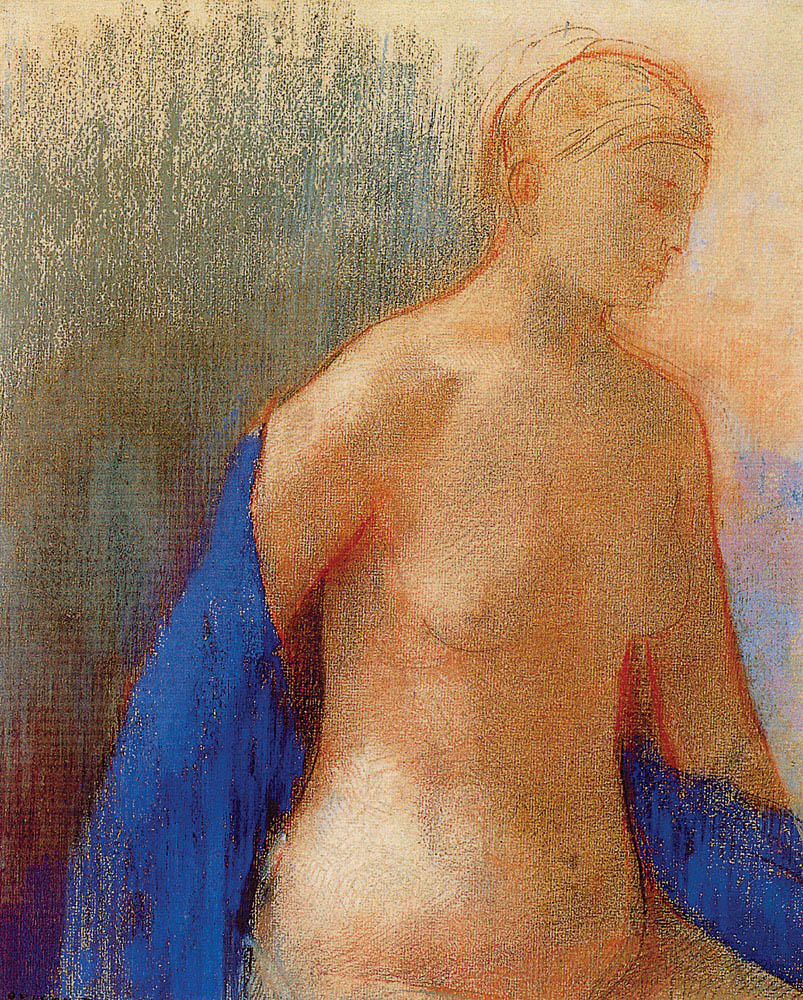

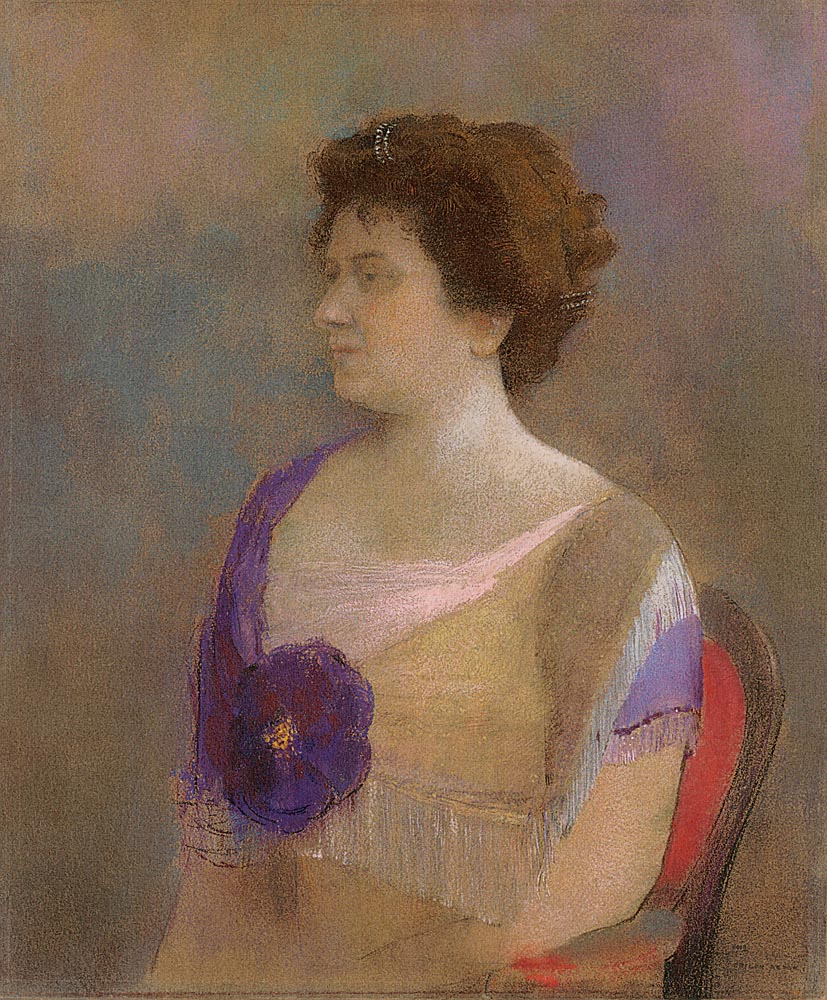

Eve or Nude with Blue Scarf, c. 1900-1905

Pastel and charcoal on paper, 44.1 x 36.5 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

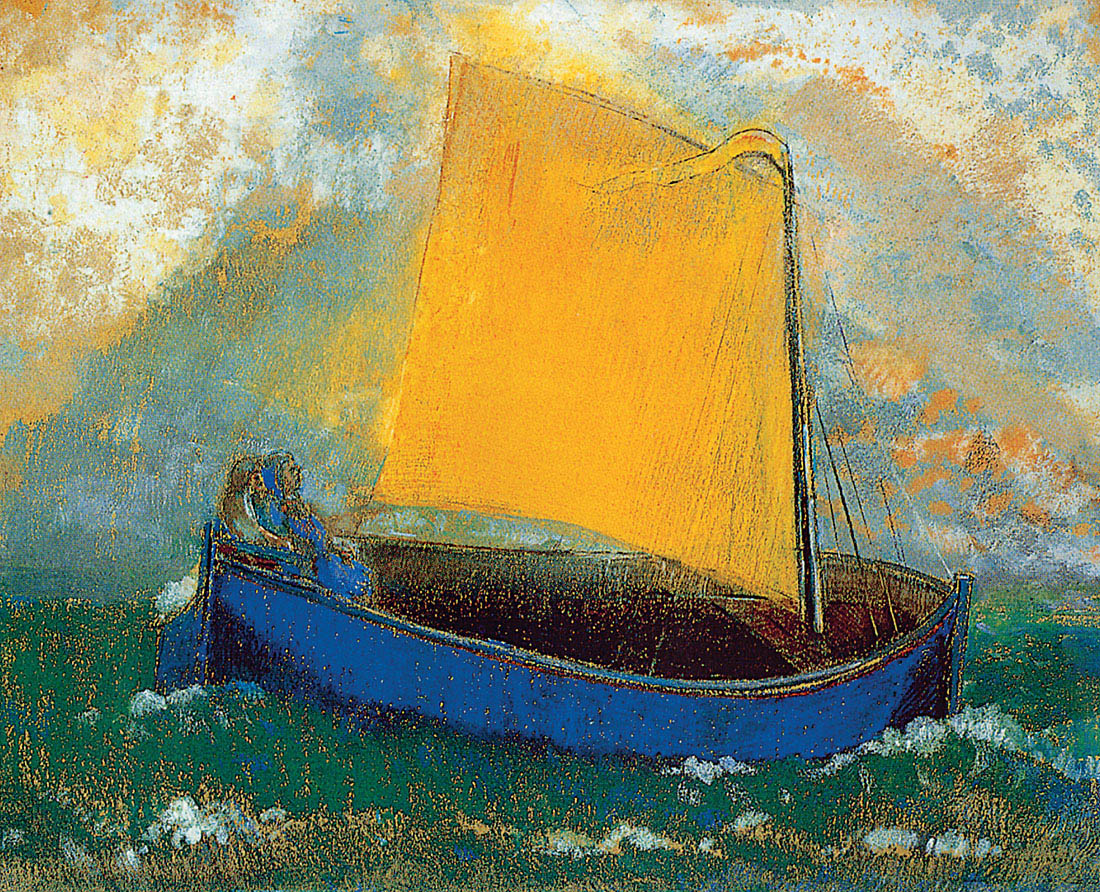

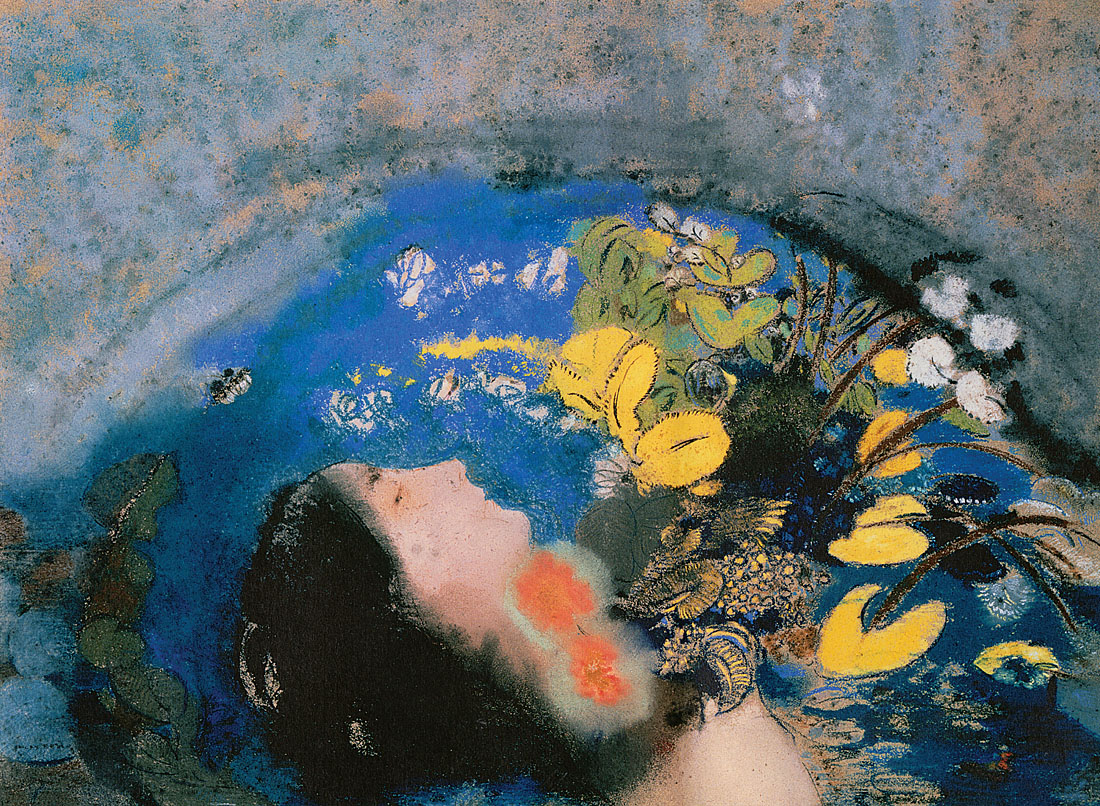

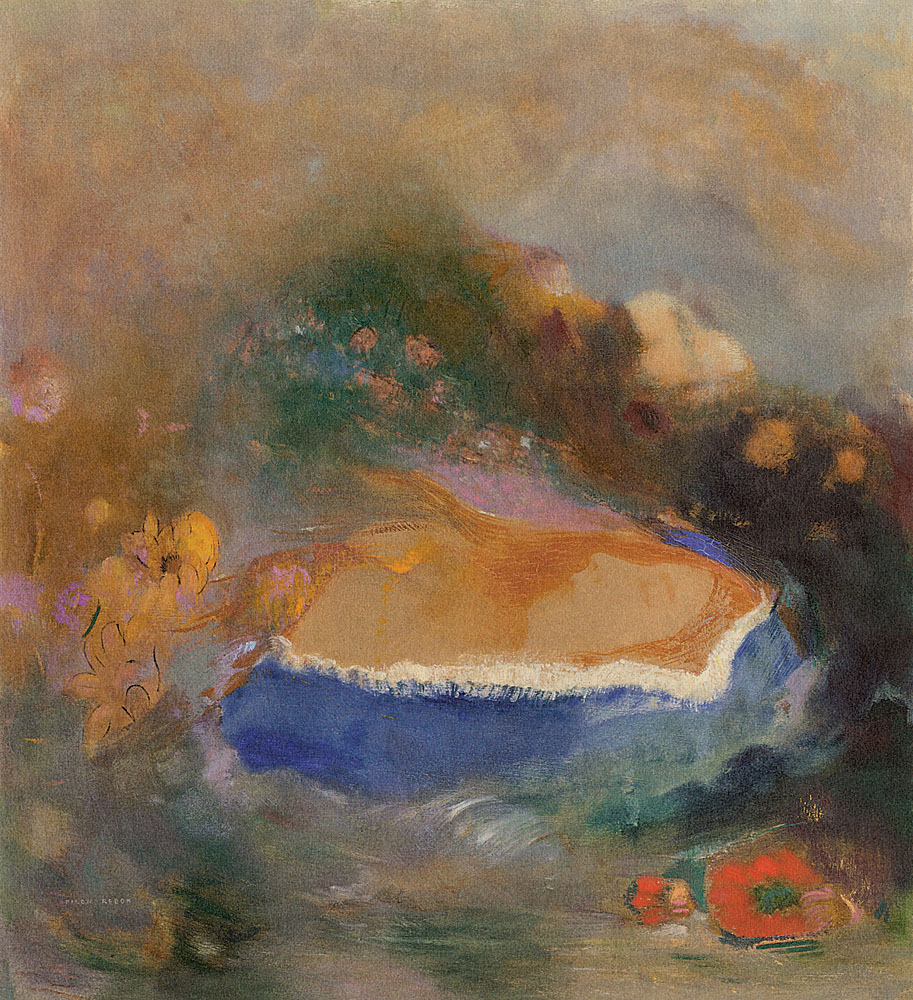

Ophelia, c. 1900-1905

Pastel on paper on cardboard, 50.5 x 67.3 cm

The Ian Woodner Family Collection, New York

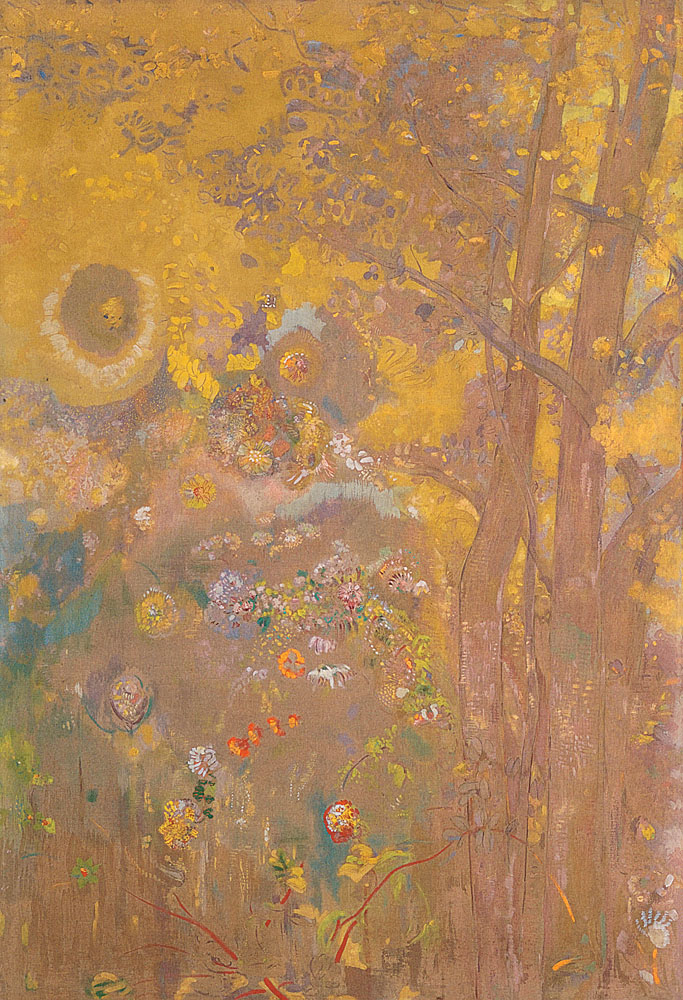

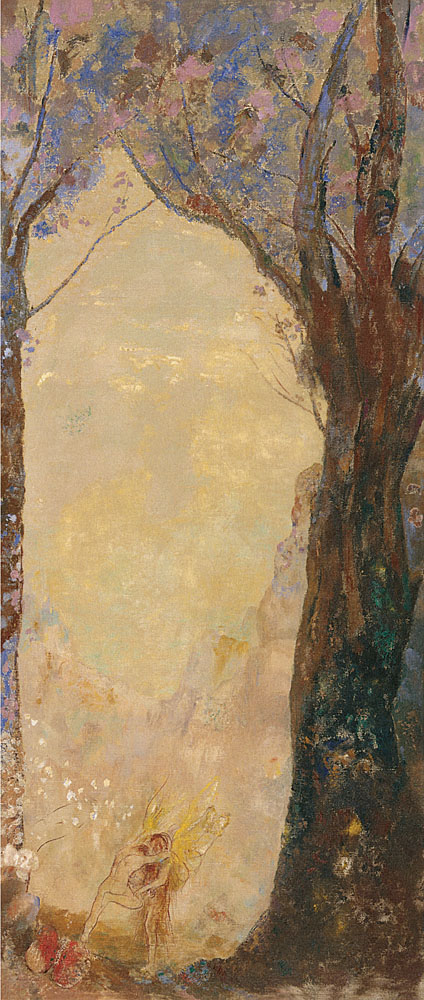

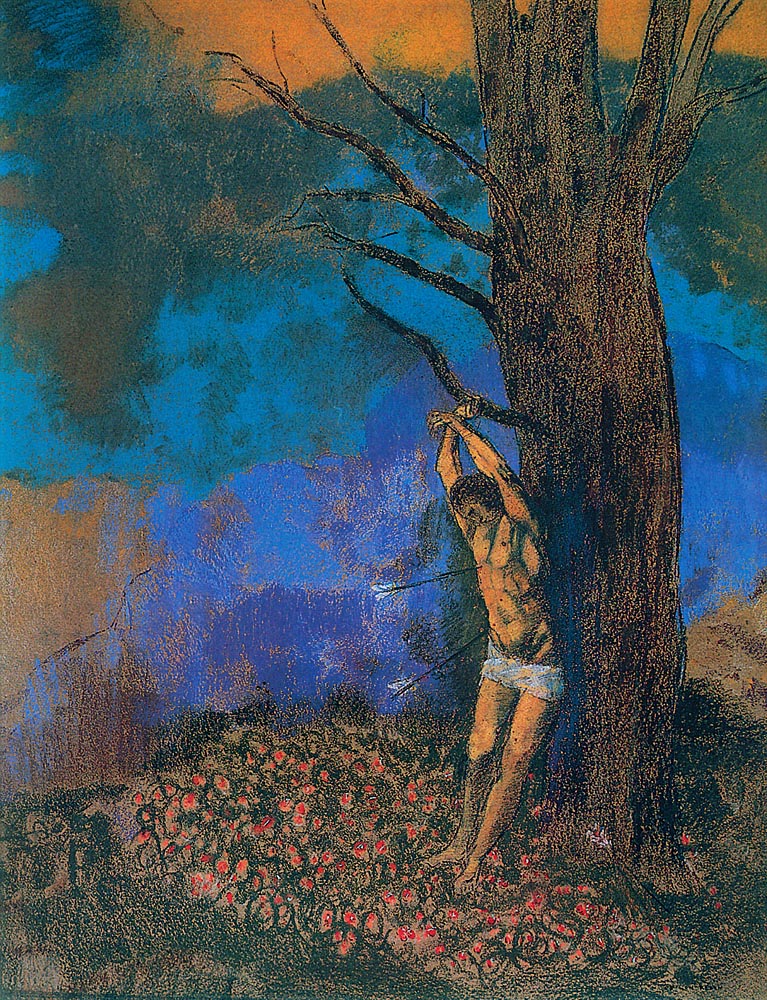

Tree on a Yellow Background, 1901

Oil, tempera, charcoal, and pastel on canvas, 249.5 x 185.5 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Engraving is completely different to the faithful photography. It does not attach any inferiority to the part that is being retraced or recreated, it is not superior, its goal is different; engraving is something else. All documentation of emotion, passion, sensitivity or even of thoughts laid out on the table or the canvas just like in a book, are sacred. That is the most precious, our true heritage.

And which nobility adorns us, poor and precarious creators that we are: the least chronic, the most precise date of a simple human act, will they ever tell us something other than what the marvels of a cathedral, the smallest scrap of stone from its walls already proclaim? Touched by man, it is saturated with the spirit of time; each era leaving behind the impact of its spiritual era. It is through art that the moral and thought-provoking aspects of life can be regained and felt. If we were given a collective power and could suddenly make an immense material chain appear on which man had left the pain and joys of his passion, it would make for a sublime read.

If I had the chance to talk to Michelangelo at the centenary, I would have spoken of his soul. I would have said that what is important to see in a great man is above all, nature, the strength of the soul that enlivens him. When the soul is powerful, the work is as well. Michelangelo went for long periods of time without producing anything. That is when he would write sonnets. His life was beautiful.

In Amsterdam there is a painting which is still in the house where Rembrandt saw it, where he placed it. The screw that supports it is still the same one that the master planted, in the place and in the lighting that he chose. In France we are incapable of keeping a piece of art in one place for a prolonged period of time.

We would not know how to write without the worry of upholding our school of thought, at every hour, in all aspects of our lives. The universe is the book we read constantly, the only source, the medium. The one culture of our mind is not enough ; we need to punish our constant reflection and follow vigilantly the austere discipline imposed upon each brain which has the desire to develop and produce, apart from that there is no style that is yours alone and reveals your true self like those of the great prose writers.

How did we cultivate our minds when there were no books? We watched the universe and the earth. And, in the writings that were based on those, man created the most moving chapter, we watched ourselves live, we saw man like now at the centre of an infinity where the mystery was neither more nor less impenetrable, and in the relationship between man and nature, we nonetheless discovered certainties, and in a certain manner, faith was also possible, also alive, the exact element that made us also think existed.

I was part of a group of young cultivated people in which I had a childhood friend: Jules Boissé. It was intellectual, elitist, one of those radiant but disinterested groups, disinterested in all powers which did not seek out art, beauty or goodness, and that would later disperse with the death of a member, or the delivery of the others to the leisure of thinking or other amateur pursuits.

Big Decorative Plant Pannels, light background, 1901

Oil, tempera, charcoal, and pastel on canvas, 250.7 x 89.4 cm and 244 x 103.7 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Trees on a Yellow Background, 1901

Oil, tempera, charcoal, and pastel on canvas, 247.5 x 173 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Branch of Yellow Flowers, 1901

Oil, tempera, charcoal, and pastel on canvas, 247.5 x 163.5 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

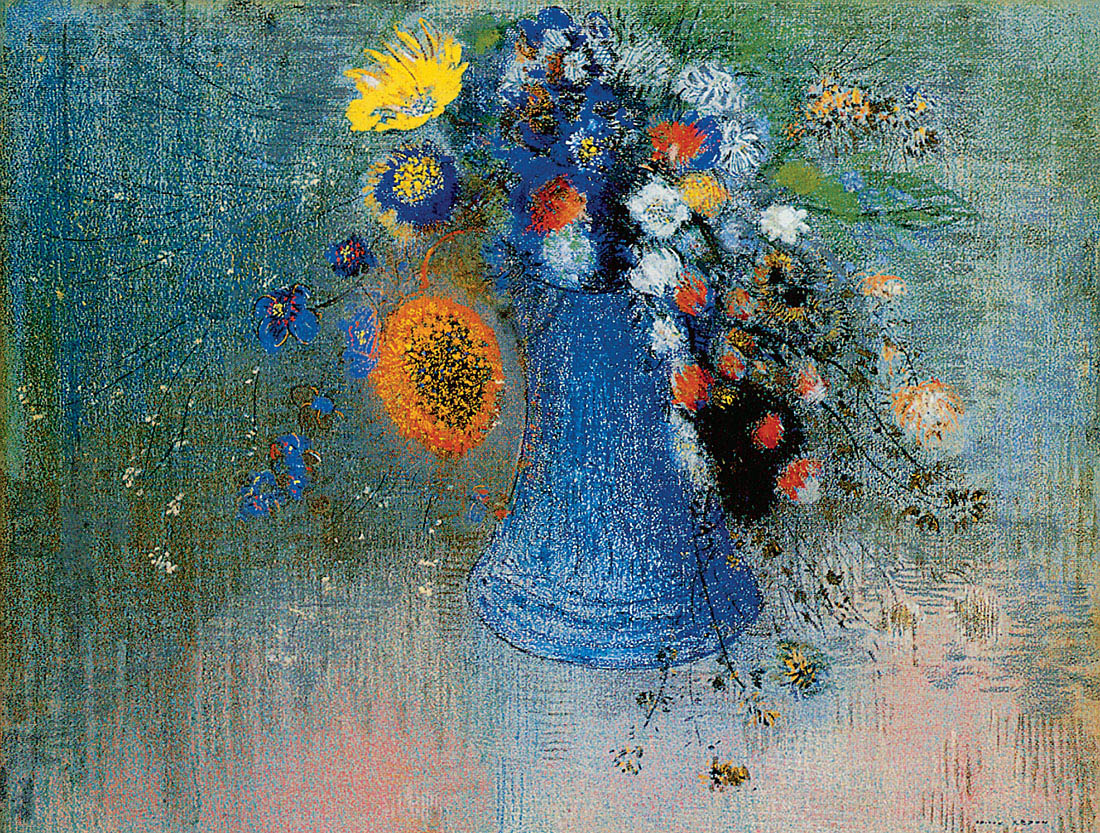

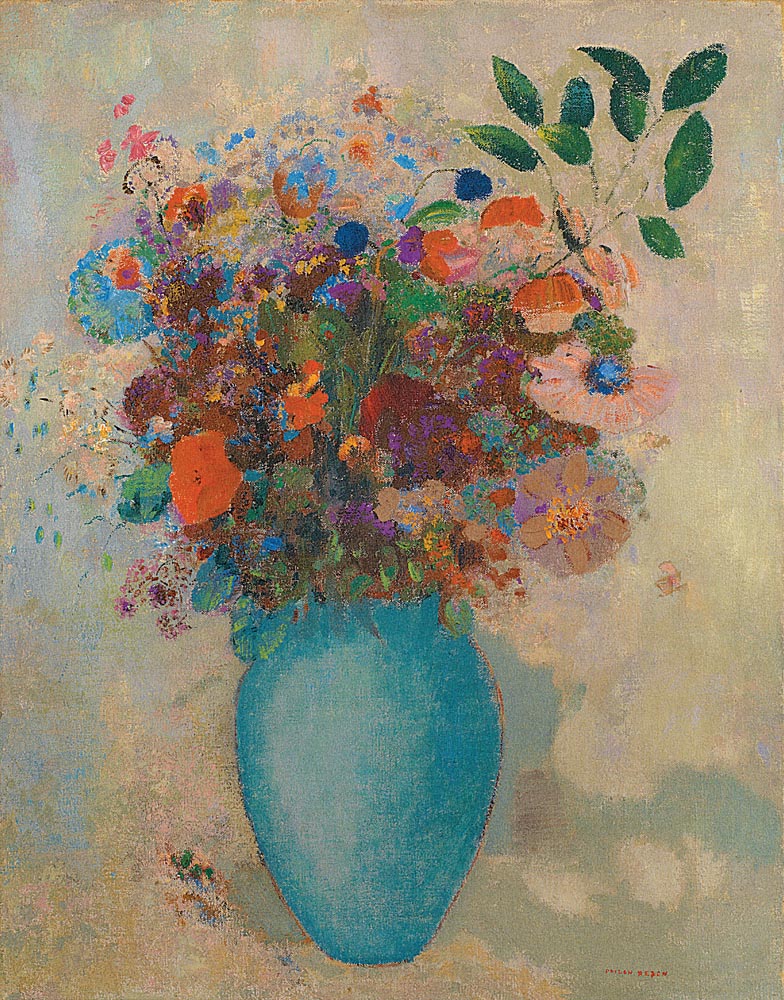

Anemones in a Vase, date unknown

Pastel, 39.5 x 29.5 cm. The Ian Woodner Family Collection, New York

The great intellectual catalyst came from the words of Chenavard who we listened to at the house of one of his students. But alas this great doubter, this deceiving analyist, enlightened us. The group had a miner’s lamp. Ready to contradict but never to confirm, skilled at speculation, out of his specious words came a feeling of unresolved weakness. He spread scruples which obliterated his sterile efforts. But his words were substantial. He also knew charming and subtle anecdotes. His stories were an open book about the men he had known, all compared and weighed up against each other. I preferred to ask him of his memories of Delacroix. What he told me gave me faith to create art.

All that was told to me of this great and vehement artist, of his life and his tastes, awoke my instincts and freed me to go on my search for fervour without torment.

Chenavard told me that he would often walk with him along the platforms, near the high walls of Notre-Dame, that lonely neighbourhood so suitable to contemplation. His friend and researcher, dazed with theories, discussed art with him, about the masters, but never managed to convince him of the end of humanity. Despite the great conversation of his partner, he sometimes said to him: “Chenavard, do not speak to me anymore, I can no longer listen to you.” Meanwhile, his fine friend continued, and when his eyes stumbled across a window which held a print of a master he liked, from Rubens or Correggio, he started to speak animatedly, it was his turn to talk endlessly…

He nearly always worked standing up, moving away from, and then getting closer and closer to the easel, either whistling or singing Rossini, whose music he enjoyed greatly.

One of his painter friends, now unknown, had the power to cast a lot of influence. This independent spirit was sometimes intimidated and would volunteer his palette to this friend leaving him in the care of making the corrections on the canvas that he indicated. But just a few strokes in, Delacroix could no longer hold it in, grabbed the paintbrushes from where he had placed them in his hand and shouted at his most intimate collaborator the most biting and spiritual insults. And then he would come back to his first idea. In public, in the world, he always had the same modesty. We know that he revered classical writers.

The avidity – nonsense perhaps – the ardour or the unbridled passion of success have degraded the artist to corrupt his sense of beauty. He makes direct and honest use of the photograph to tell him the truth. He thinks, whether it is in good faith or not, that the result is enough when it can only give him a fruitful indication of the raw phenomenon. The cliché transmits only death. The emotion felt in the presence of nature itself will always provide an amount of otherwise genuine truth, controlled by him, alone. The other is a dangerous conversation. I was told that Delacroix had insisted; I doubted it. His words were to be checked.

Gustave Moreau is an artist who does not possess and will never possess all the fame he merits. The excellent quality of his spirit and the delicacy he applies to painting, places him apart in the world of contemporary fine art. He creates little or at least he appears less, judging from the rarity of his exhibitions; but he still creates with certainty, in the safety of his talent which demonstrates somebody who knows exactly what they are looking for, what they want. The bright and glistening watercolours which I would call historic watercolours, demonstrate this perfectly, leaving room for new charms in his style, a little stiff and a little rigid.

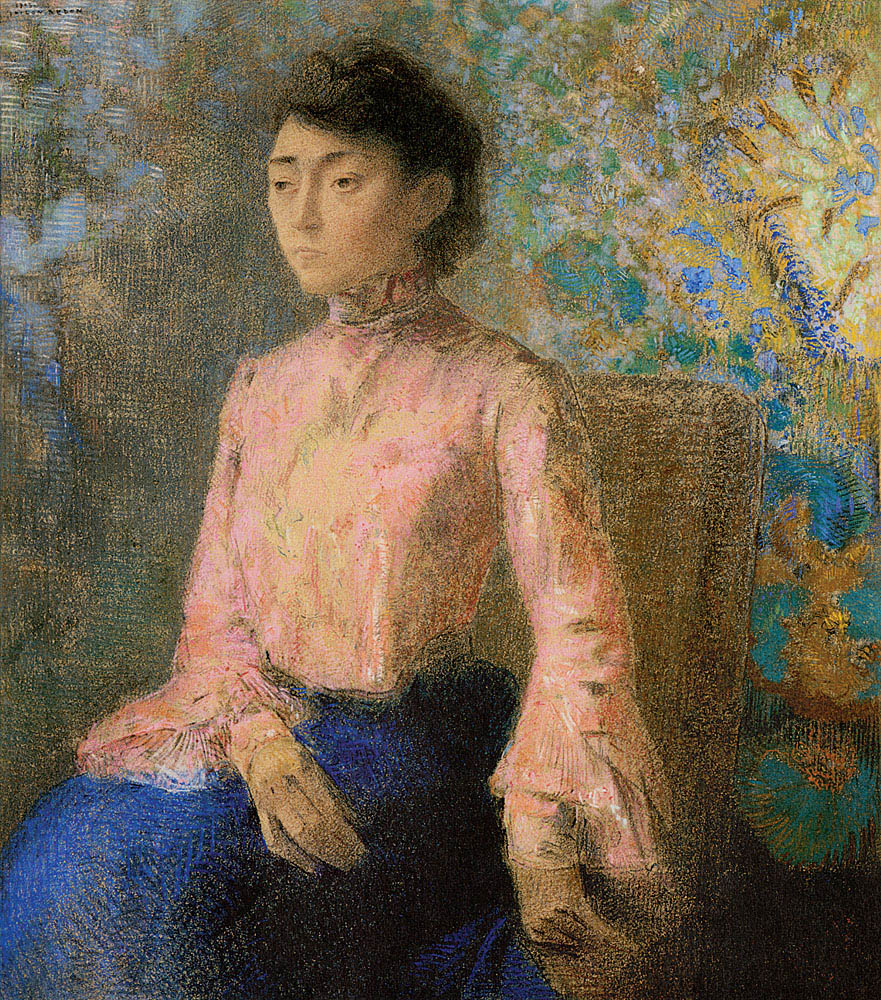

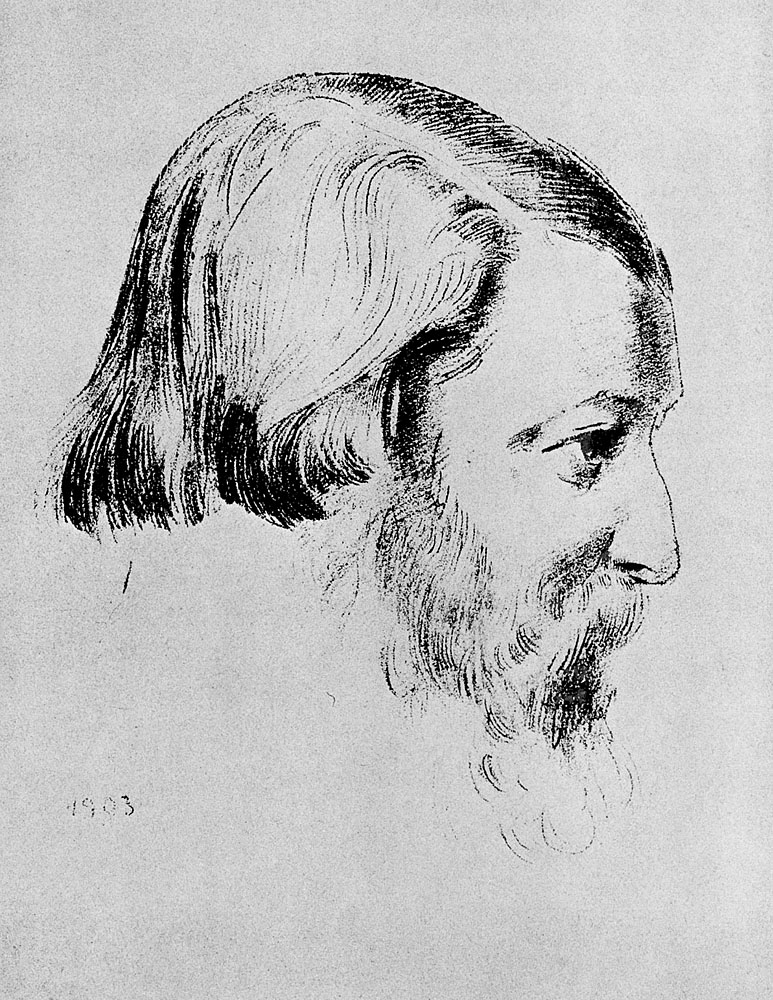

Portrait of the “Nabi” Painter Paul Sérusier (1864-1927), 1903

Lithograph, 16.5 x 13.8 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

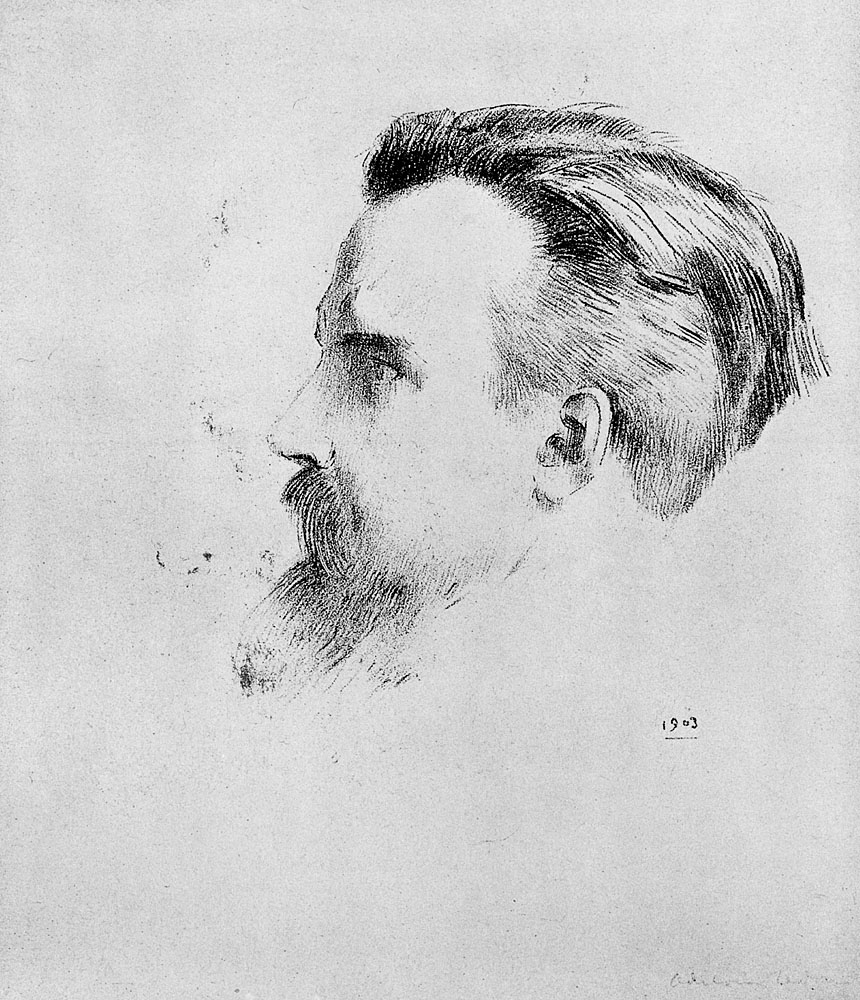

Portrait of the Painter Maurice Denis (1870-1943), 1903

Lithograph, 14.4 x 15.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

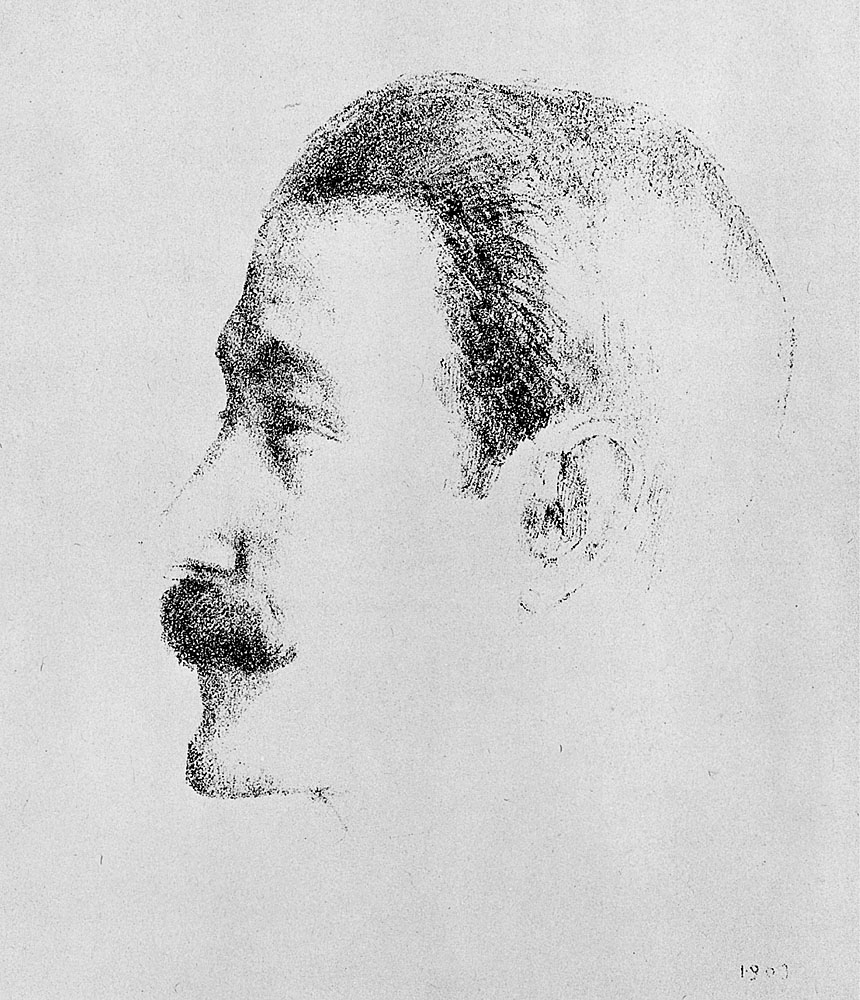

Portrait of the Pianist Ricardo Viñes (1875-1943), 1903

Lithograph, 13.7 x 11.4 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Portrait of Juliette Dodu (1850-1909), Heroine of the Franco-Prussian War and Half-Sister of Redon’s Wife, 1904

Lithograph on light gray China paper laid down on ivory wove paper, 14.6 x 9 cm. Art Institue of Chicago, Chicago

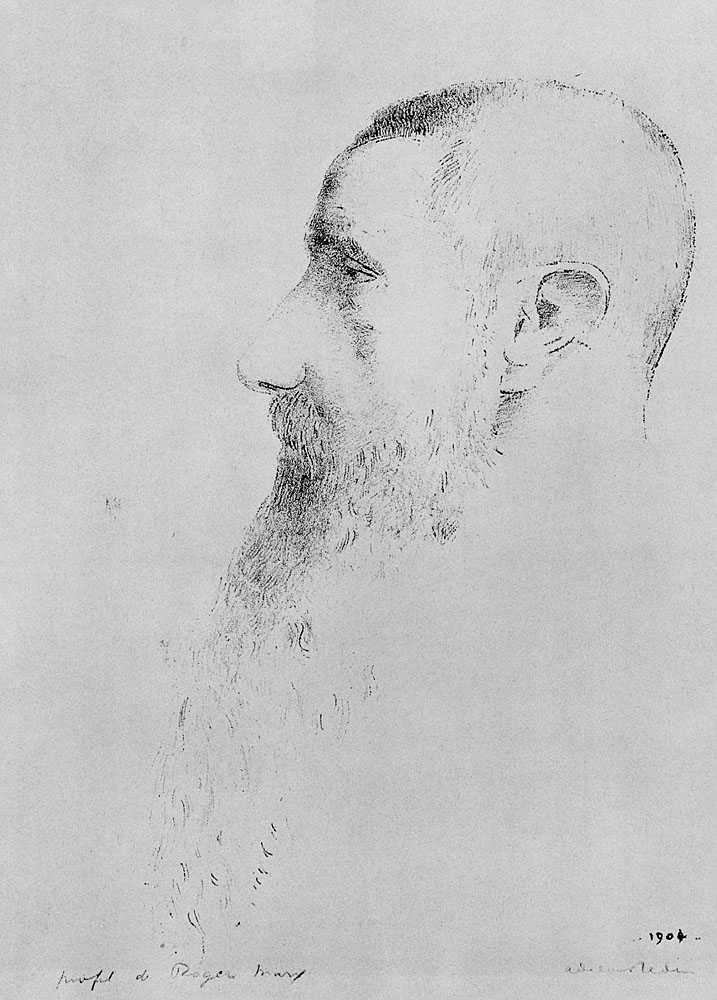

Portrait of the Art Critic Roger Marx (1859-1913), Father of the Critic Claude Roger-Marx (1888-1977), 1904

Lithograph on light-gray China paper laid down on ivory wove paper, 25 x 14.5 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

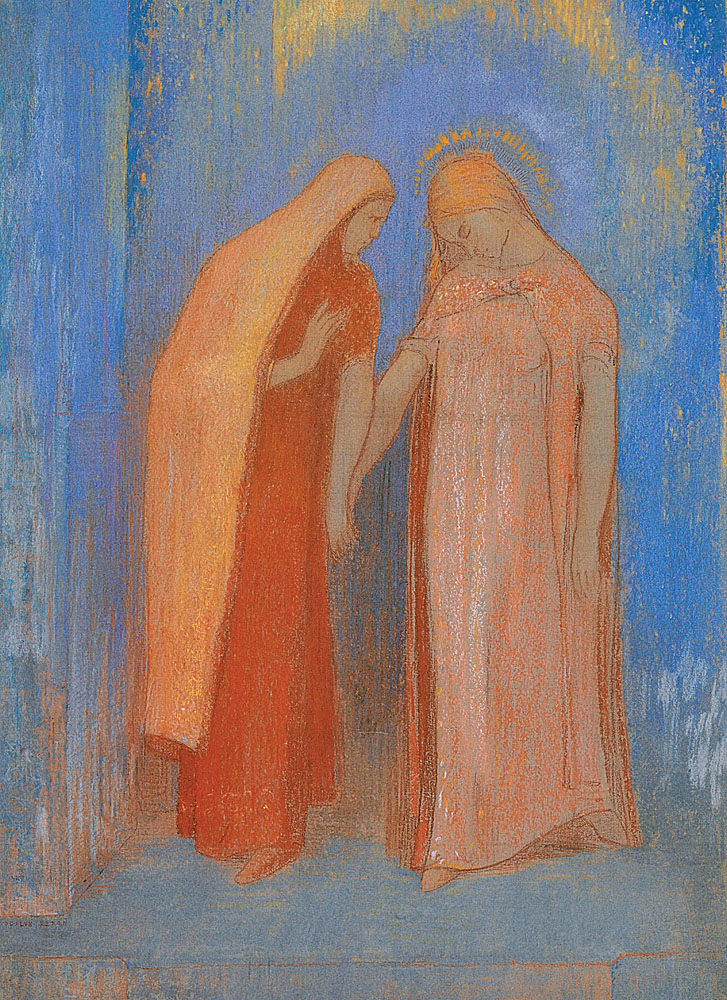

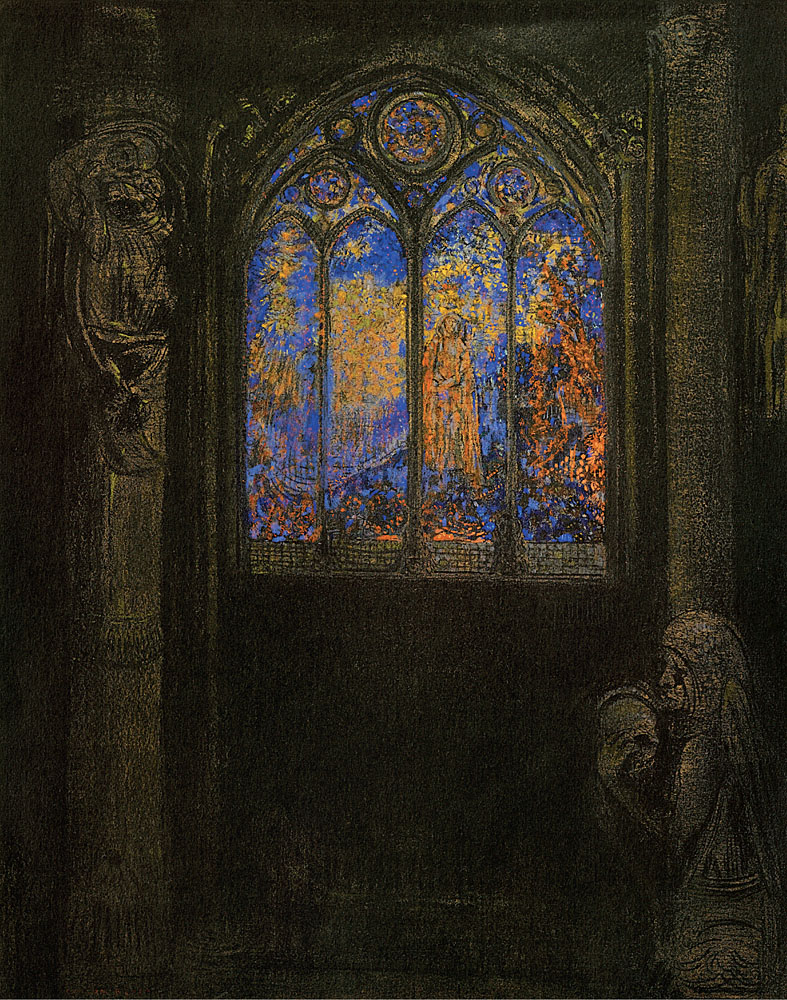

Temple vitrail (Church Window), 1904

Charcoal, pastel and stump on cardboard, 87 x 68 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

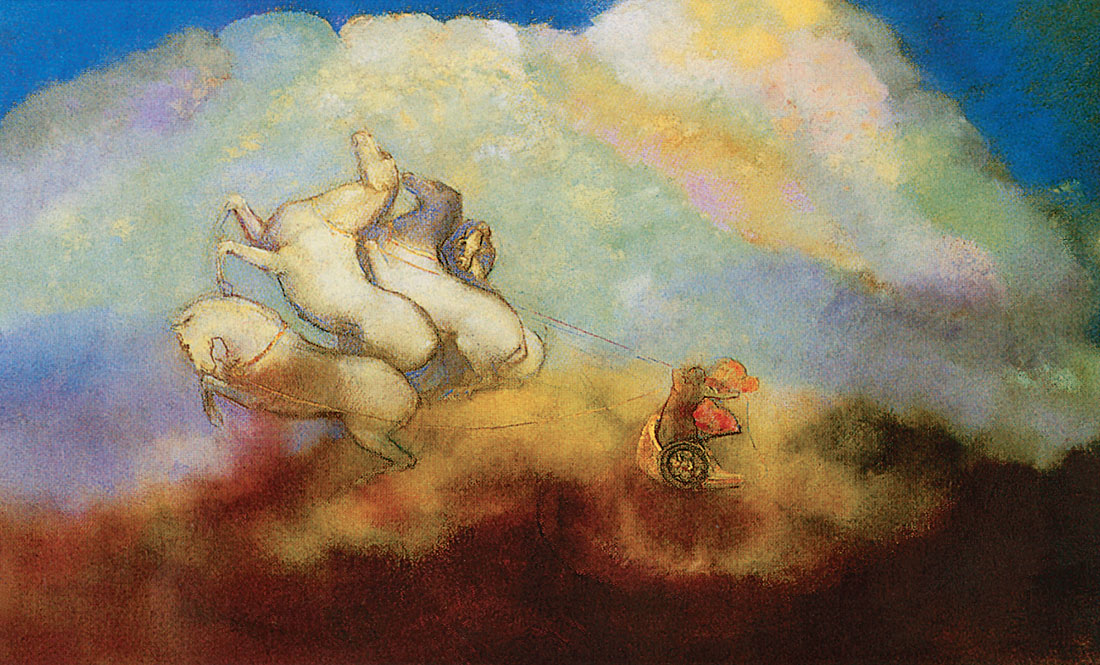

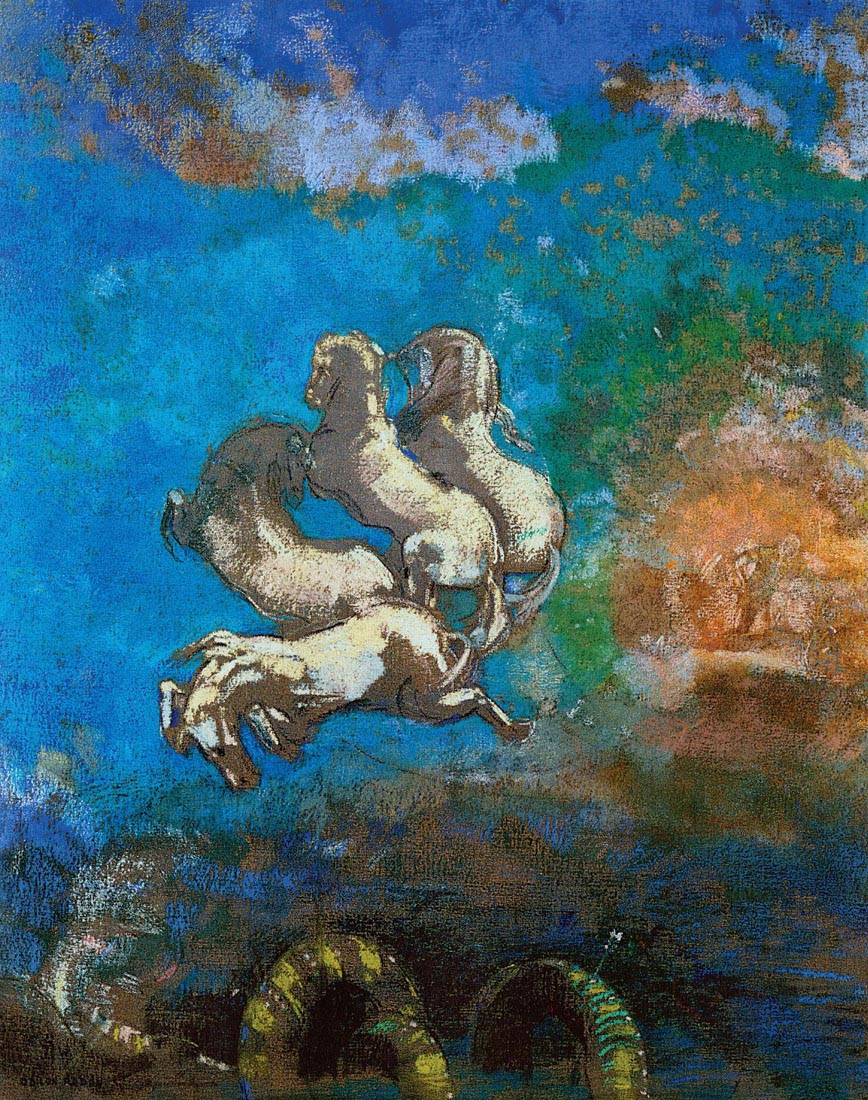

Most notably, The Fall of Phaethon is an art work held in high regard. I do not know which memory of Delacroix’s lovely sketches strikes me most in the presence of this dazzling page from which the daring and novelty of the vision could go hand in hand with the creations of this master. Delacroix has more freedom, more abundance; the strength of his imagination has brought him towards more varied subjects in history; he certainly has more passion, and the supernatural light which falls on the entire piece of art holds it apart and in high regards at the Olympe. But I see in Moreau more excellence in the meticulousness, an exquisite and delicate penetration of his consciousness as a painter. He knows what he wants and wants what he knows, consumed as an artist and irreproachable. He is like a writer who hones his skills without losing the good development of his ideas. An admirable reasoning guides the direction of his imagination.

This Fall of Phaethon is a concept full of audacity whose object is to represent chaos. Have we never imagined anything of the sort? I do not know; nowhere has the representation of the fable been created with such an emphasis on the truth. In the brightness of these clouds, in the bold divergence of these lines, in the bitterness and in the bite of these bright colours, there is a grandeur, a commotion and in some ways, a new astonishment. Take a look at the countless illustrations of the fable that others have interpreted one way or another, I defy you, if you have for a moment stooped under the cold vaults of the academic temple so as to find a spirit which makes the antique look younger with such a freedom and in a form at the same time so contained and so vehement.

This master (because he is one, you must give this title to those who demand enough from others and themselves to achieve their growing orgininality) has not stopped painting the legends of pagan antiquity since he started, and he continuously presents them under a different light. It is because his vision is modern, essentially and profoundly modern, because he gives in gently to the indications of his true nature.

We published a little on the art of drawing; there are an abundant amount of books and brochures of every other subject but on drawing it was lacking. Popular curiosity, from which a deeper fondness leads to reading, only has a few opportunities to take effect. Apart from some pure aesthetic traits or other works giving an overview of the schools and beauty – works which only address those already cultivated and special minds – the public which likes fast reading, will not find much to gather here, in favour of the annual exhibitions the organisation has recently moved to the province. They can therefore cast an eye on the daily papers, the analyses, that they had themselves observed. But these sorts of accounts, based on true events, do not allow those who publish to step away from a particular piece of information, where the end is not the instruction. However, the critique standing between the appreciator and the artist is often so due to the first’s personal ideas and preferences, those which have a non-decisive influence on the artist.

Articles capable of giving some growth to though are produced in reviews, this new type of book where some distinguished minds deal with more generalised questions. But these sorts of publications do not fall into the hands of everybody, only the specialist has to worry; as long as the unrefined amateur for who art is a luxury, keeps to his pastimes, he can only make the most of it once the article of the review has been mediated and gathered, having taken the most sturdy and determined shape of the book. Well these books are lacking! Not many thinkers have turned their thoughts to the arts and let us add quickly too that the militant publicist, the one who addresses themselves daily to the public, does not worry more about it.

It is in winter that music is at its most prestigious, it is especially pleasing in the evening, in agreement with the silence to please the imagination that it arouses: it is a nocturnal art, the art of dreams, but the painting comes from the sun. It is born with light and day and that is why at the start of each new season, when the landscape artists head towards the fields, the Parisian amateur turns in preference towards colour and life like a gentle rest after the winter and late nights.

The great natural sagas of the current epoch have played a bigger part in beauty than other poems from the great centuries. All the souls and divine aspirations of a generation live in them. The sagas are the great monuments of humanity: the pure literary works say much less, the translations themselves already lose some of their beauty, they are restrained and limited in time, and only for that deserve a secondary importance.

With regards to individual sagas, they are superficial and more strictly literary; they reveal little and do not have long-term chance. They could be removed from the literary shelf and history would not have lost its most important documents.

1878 – Voyage to Belgium and Holland

Haarlem, 20 July – It feels as if I am the end of the world; I write weakly, with the inevitable sadness of a newly arrived. I am experiencing a child’s fear in this morose, half-obscure country, full of silences and where the moving skies make me feel ill at ease. And then I have the instinctive defiance which is born on foreign soil. Why do I have to say it? It has only been twenty-four hours that I left but I already have a devouring desire to hear French being spoken. I would have retraced my route in the middle of the journey if the train had not brought me through marshlands, water, seas, boats and especially the windmills which reverberated to the horizon, low and monotonous. The countryside which rolled by in front of my eyes was well known by me; I had seen it many times before in the Louvre, in the gallery of the masters: in the foreground upon lush grass, thick and of a powerful colour, cattle are grazing on the wet ground; in the background, a few ponds, some trees semi-submerged; then the mast of a ship which incites a bit of a surprise to see it travelling through a meadow, being towed gently; then the windmills, there are always windmills turning at full speed, all orientated invariably and in parallel under the omnipresent strong wind. Man is hardly present; he loses himself in the heavy and troubled atmosphere and has no bigger picturesque role than the house, the path, the animal, or the cloud, which is always full of rain, but strikingly beautiful. Everything is broken, without visible contours. The only drawing of this landscape is in the rigidity of this unique horizontal line which cuts the painting in half, and extends infinitely before you, around you, with a strength not lacking in grandeur.

This is poor and sad, devoid of all interest in the view, nothing of splendour, nothing from outside provokes a marked surprise, fertile, durable, like in the decorative regions where paintings are made at each step, with their frames, their lines and their plans. My biggest surprise was in Rotterdam, the most grandiose and picturesque of these unfortunate vicinities; but still her beauty belonging to this order of things out of the ordinary, where nature imposes itself on man or where it is not expected to compete above its level.

21 July – I run with haste to the painting and I find life; entering this room of the Academy of Haarlem where three-hundred faces are looking at you so arduously, I thought myself in the middle of a crowd in a bygone era, at the time of Frans Hals himself.

He was an extraordinary painter, who from the start until his end, revealed eight complete canvases. His maturity as an artist came late, around forty years of age or older, and the art work of his old age is the surplus received from an unheard-of organisation which, to put it this way, never wants to weaken. If ever the genius proves that nature makes exceptions for geniuses, it is of course here, in the presence of his most supreme and final works created before death and without decreasing in the hand of an eighty year old worker. There was there a vision of painting that would only be born two hundred years after him, by his French realist contemporaries, from the decadent, from the new no doubt.

This excessive singularity of an extreme art created so far from Paris, this refinement of a vision discovered two centuries before bears such a surprise, as if time and place did not exist for the genius. Art is a flower wilting freely, exempt of all rules; it appears to me that he single-handedly disturbs the microscope analyses of the knowledgeable aestheticians who explain it. Maybe the ethnicities, the delicate study of temperaments and their fusion into a population could provide a pre-emptive explanation without reminder, once we speak of Rembrandt, Shakespeare or Michelangelo, these prophets. Frans Hals, who was not, was however the most powerful man who translated the pinnacle of animal life.

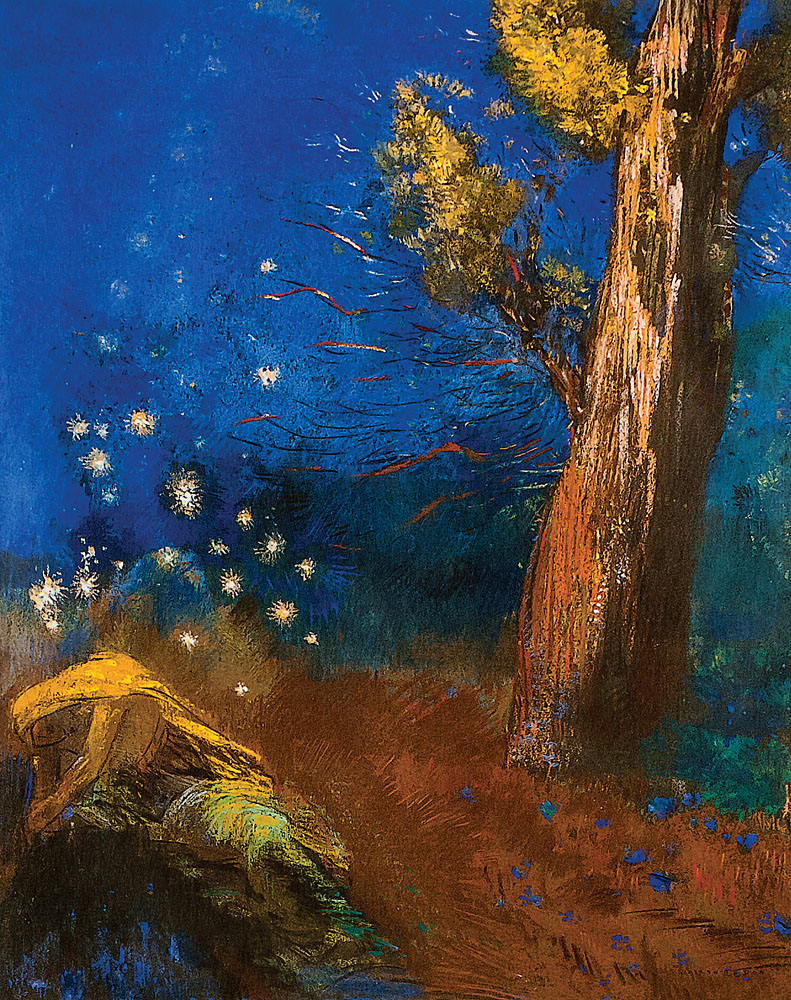

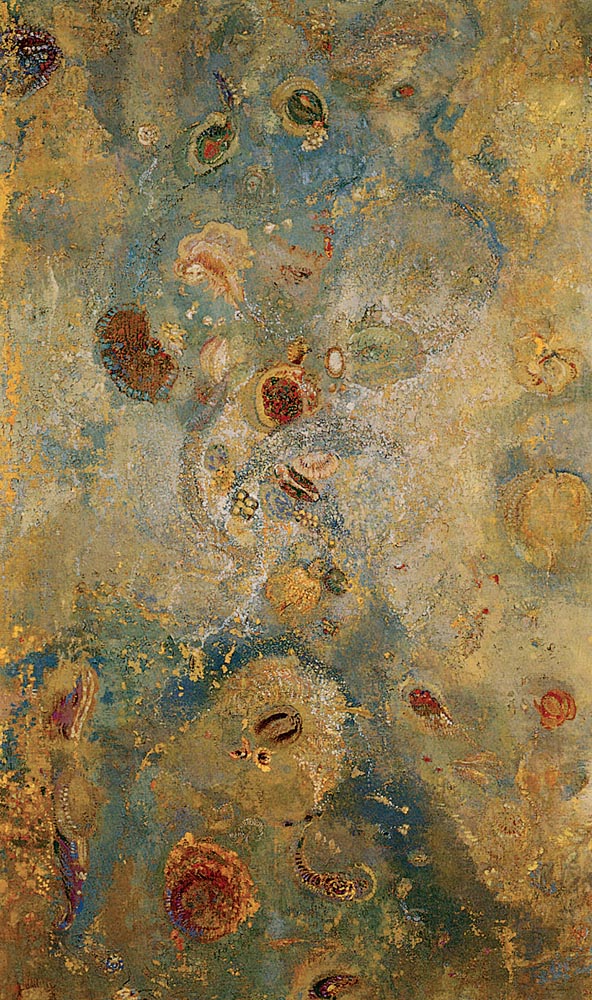

Animals at the Bottom of the Sea, date unknown

Pastel, 60 x 49.4 cm. The New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans

27 July – I see the Hals once again, they appear to be a hundred times better than those of Rembrandt, already up there with the best. From life and from life again, but only from animal life. I question these faces, they tell me nothing. I see them living foolish lives. The memory of the syndics executed in the memory of Hals painting that Rembrandt must have known or at least he knew the works of, still haunts me today.

In his last method only, Hals appears to have reached superiority. Is this a weakness of the hand, is it a decrease of too many sensitive physical forces of this excellent worker? First of all, in the works dating from the last years of his life, there is a marked softening in his execution; but what singular ease, what disdain for detail, what strength to see finally, quickly, and grandly, the true reality. There is an eye where we sense the height of his power. Near the end, Hals is a master. More so, at the moment he has connections with a few charming contemporary French painters. Did they imitate him? No. We would have to establish a connection between the intransigents and these works; we will find what is legitimate, sincere and new in the research on French realists.

Surrounding me are figures blossoming with the freshness of a carnation which gives desire to paint it. All these heads that live and pulsate around me stand out against a dark background in a clear and rich manner unknown to any French land.

Amsterdam – The Night Watch – a bit of disillusion. However, after inspection, the charm becomes apparent. Hal’s life, so intense, negatively affected him, however, the superiority of his genius wins over, for in places, at the right of the painting, it is superb – the obscure parts have darkened without a doubt; maybe the dimensions of the painting bypass those of perfection in visual arts – abstraction makes the sum of blood life I saw in Hals, the painting has a profound and strange charm – everything in the half-shadows is better than what is in the foreground. What is more understandable in the work of this master? Yet again, in places, there are faces that looked at from afar, take on a magnificent magic. From that magic, that is the right word – the quality of the light is fairy-like and supernatural. Suppress those two or three characters in the foreground, the rest is magnificent.

Syndics of the Draper’s Guild is more perfect than The Night Watch, its intent less superior.

No master painted drama like Rembrandt. Everywhere, even in the most insignificant sketch, the human heart is concerned. Rubens had the genius of setting a scene.

1879, Antwerp, 5 August – Dare I admit that Rubens speaks a language that I do not understand! Assuredly, he reveals a strength of this spirit in its biggest measure; I don’t think I have ever seen such an excess of action and truth in gestures, attitudes, expressions and the variety of expressions, as it comprises of a vast and varied subject, never has so rich an invention in canvassing appeared so intimately supported by the depth and the touching beauty of thought: the people, the executioners, the thieves, the children, who are always gracious and charming like we can see in the good people of Flanders. The women, all natural and honest in their beauty that they ignore, like the infinite Madeleine that you can see at the base of the cross with the feet of the holy dead on her young shoulders, and whose pain is so profound it would make me say that Rubens knew how to paint goodness. All of that captivates and animates me. I feel good in the presence of a true superior creation and yet I refuse to give in to his genius: something contradictory prevents me from understanding him, from loving him.

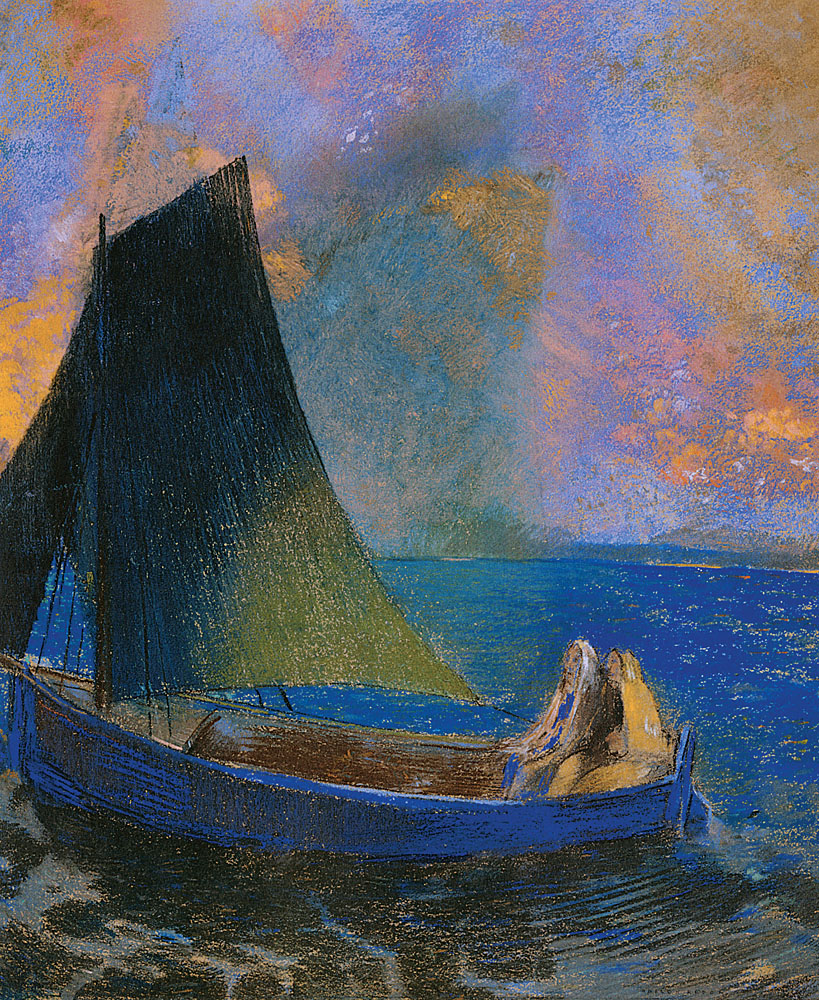

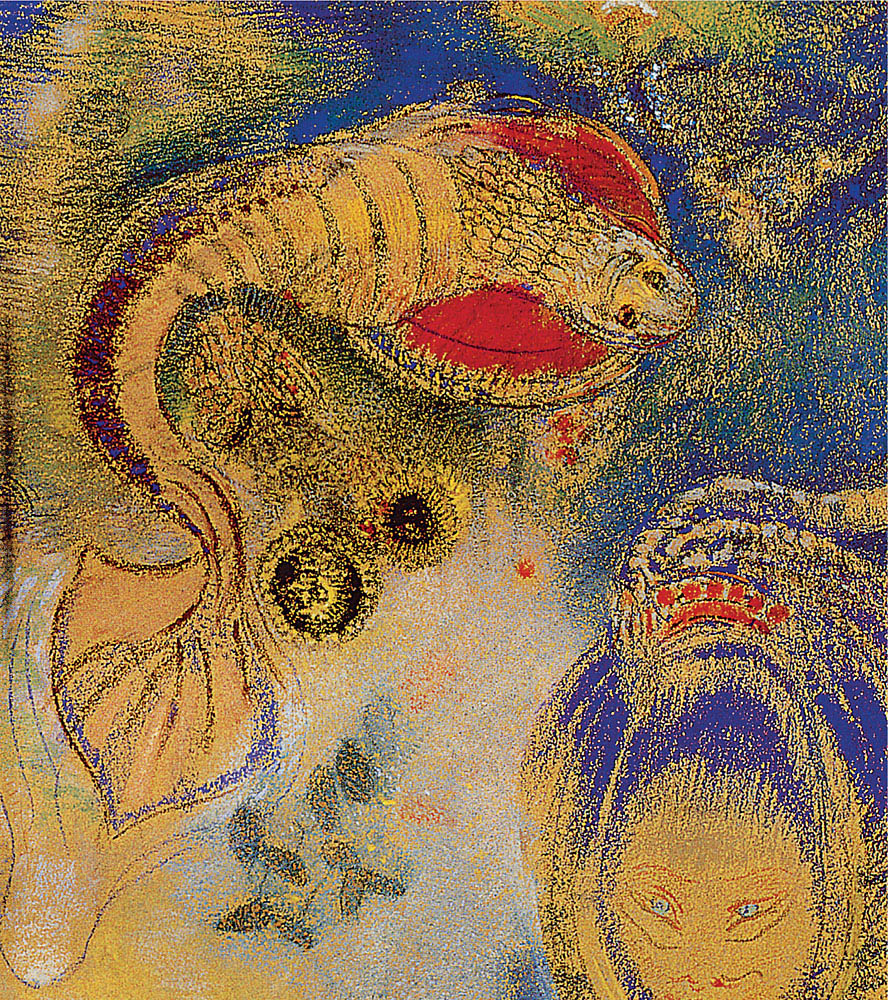

Oannes or Christ and the Snake, 1907

Oil on wood, 65 x 50 cm. The Ian Woodner Family Collection, New York

Let us say that Rubens was a master of decadence – we would not say that of Rembrandt – he belongs to the diminishing era of ancient art because he did not really do anything new. He is a boiling genius, full of ardour and ideas, who lived the high life, painting on church walls, in palaces, in the middle of courts, and portraits of princes he was a friend and a favourite of; he did not suffer; – although it cannot be confirmed – this long and painful martyrdom of applying a new ideal. He is not a colourist – that could appear paradoxical – but I would not say that these same reds, these same blues, this customary illumination of each object, each piece of cloth, is the primary title for his glory. A simple greying of his contains as much as a painting executed with complete precision. That is what he reveals from the first moment, the grand idea he has made himself of the scene he will paint, he shows it with one stroke, in all its grandeur, its masses, its truth: he has understood the crowd, he has seen it; he has painted pain, goodness, grace, abandoned beauty of children and women; I think he touched the most sensitive fibres of the human heart. He has without a doubt all the supreme cords of the eternal lyre great men used to speak of the worries of our destiny. He has all that and not one shadow of a doubt, not a hint of visual representation – he has no line, no plan, no simplicity, not anything used for the clear and good presentation of things. In this he has a kinship with the English school; he does not generalise anything by the line that he appears to doubt – I mean the right line, this active and decisive abstraction, without which the shape, as well as the painting, have no life. He draws whilst constructing each object, each person, with such strength that he admirably knows all the muscle characteristics of the human body. In that respect he is modern, he prepares these personalities from the North who, like Delacroix most of all, express the life of things much more by a reflexion of the nature in their memory rather than by observation or the immediate analysis of the model.

He has all these grandeurs, all these talents and their riches, but he did not suffer; it is perhaps the only reason for my refusal to place him amongst the greats.

In the temple of love that we raise in the spirit of great men, there are two cycles, two distinct places that it is important to separate: in one we find the biggest masters, alone and suffering, weighed down by the weight of their own great misfortune.

Where is the limit of the literary idea in painting? Let’s understand each other. There is a literary idea each time there is no physical creation. This does not exclude the creation, but an idea that could explain the words, that is subordinate to the impression created by the purely picturesque stains which are of secondary importance and in some manner, superfluous.

A painting made this way leaves a lasting impression in the mind that the spoken word would not be able to replicate, the sole exemption being the spoken word in the form of art, a poem for example. In a literary composition, no impression is made. The effect resides only in the ideas that it bore itself and that are produced by memory. There is therefore no real piece of art; a story would be better; it is a pure anecdote. For example: in Rembrandt’s The Archangel Leaving the Family of Tobias there is another expression other than the purely visual, the different stages of life and the manner of feeling wonderful are they not rendered with an infinite delicacy in this old man who falls ruined into divinity; in the adolescent who admires but also analyses, looking, questioning; in this woman who joins her hands together and prays, in another, older, who disappears into the background and lower down, in this barking dog who seems to represent the brutish in his terror and fear?

These nuances are certainly in the domain of literature and even of philosophy, but we feel that all that is only of secondary importance and that the artist thus intentionally or unintentionally did not create a unique setting for their painting. And the proof is that all this touching research, so naïve but profoundly true, is only apparent after a long analysis, and that the majority of spectators who have been hit by this wonderful piece of art, were under an impression that did not come from there; the unique emphasis of this sublime composition is in the supernatural light that illuminates and basks the divine messenger in gold. There, in the pure and simple nature of tone, in the subtle delicateness of the chiaroscuro, is the secret of the entire work, a picturesque invention that incarnates ideas and gives it, to put it bluntly, flesh and blood. This has nothing to do with the anecdote.

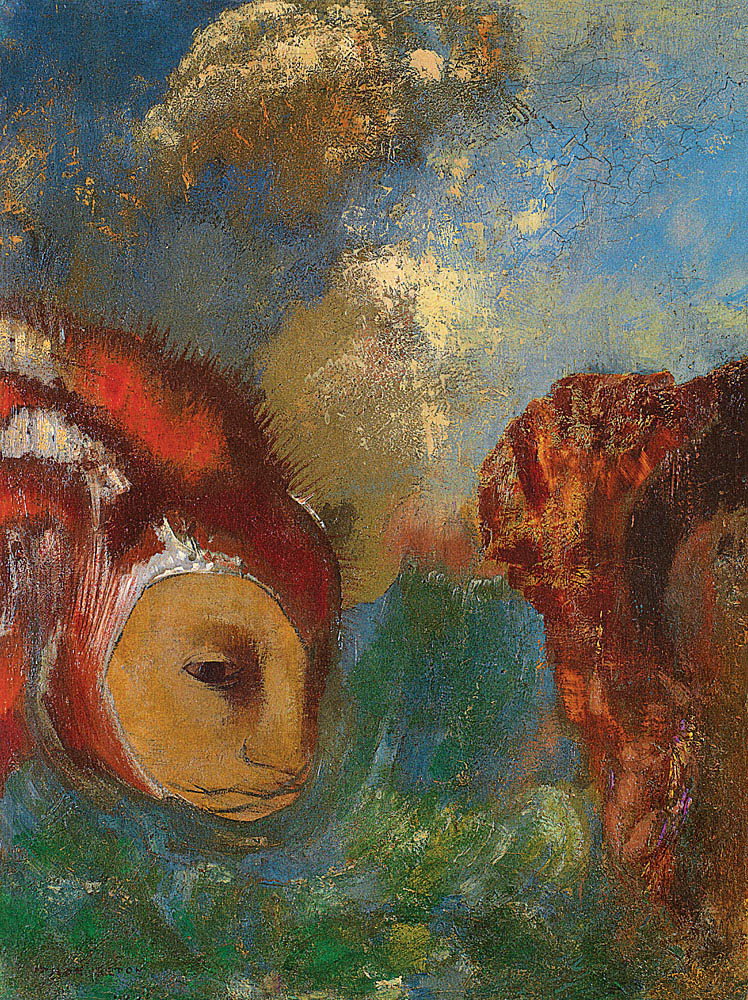

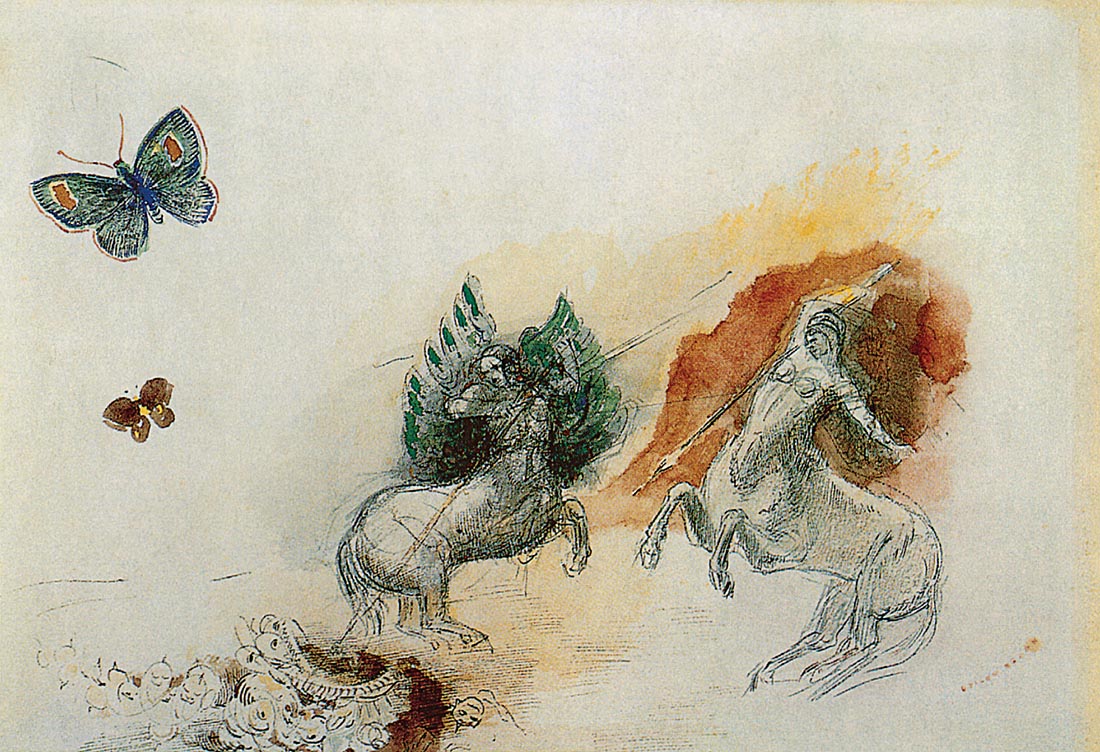

Fight of the Centaurs, after 1910

Watercolour, ink, and conté crayon on paper, 17.8 x 25.3 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

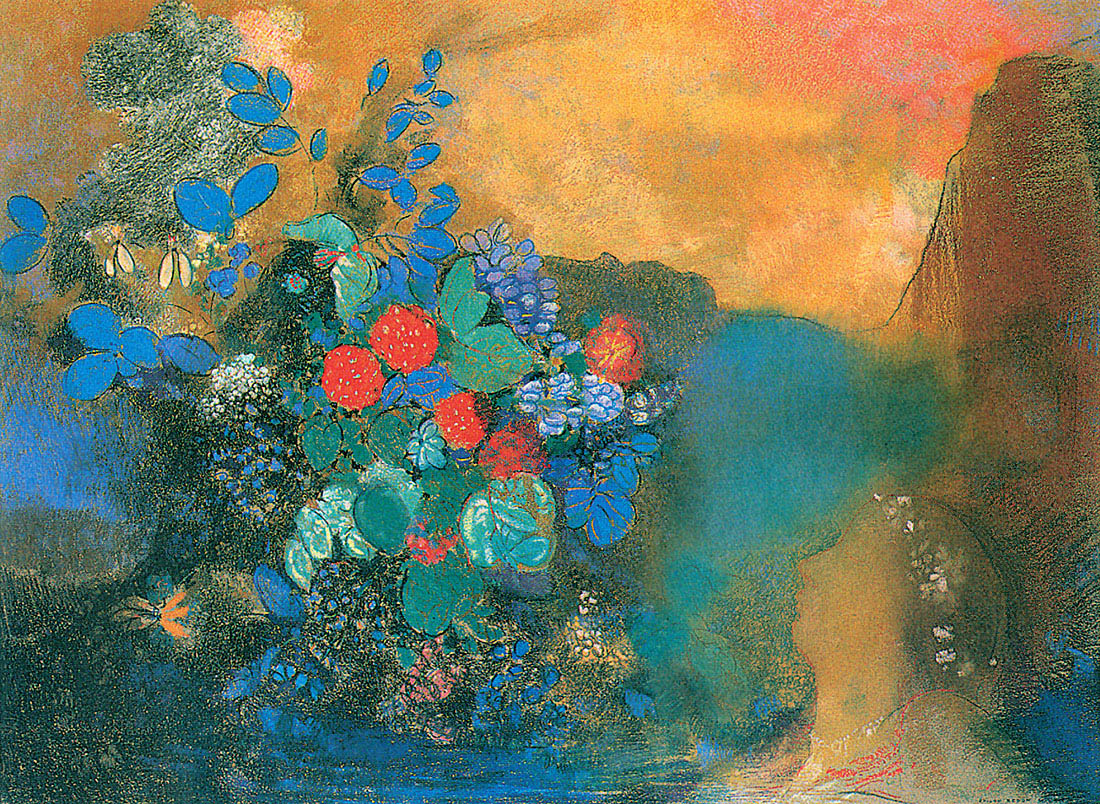

The Anemones, c. 1912

Pastel on paper laid down on canvas on cardboard. Hahnloser/Jaeggli Stiftung, Villa Flora, Winterthur

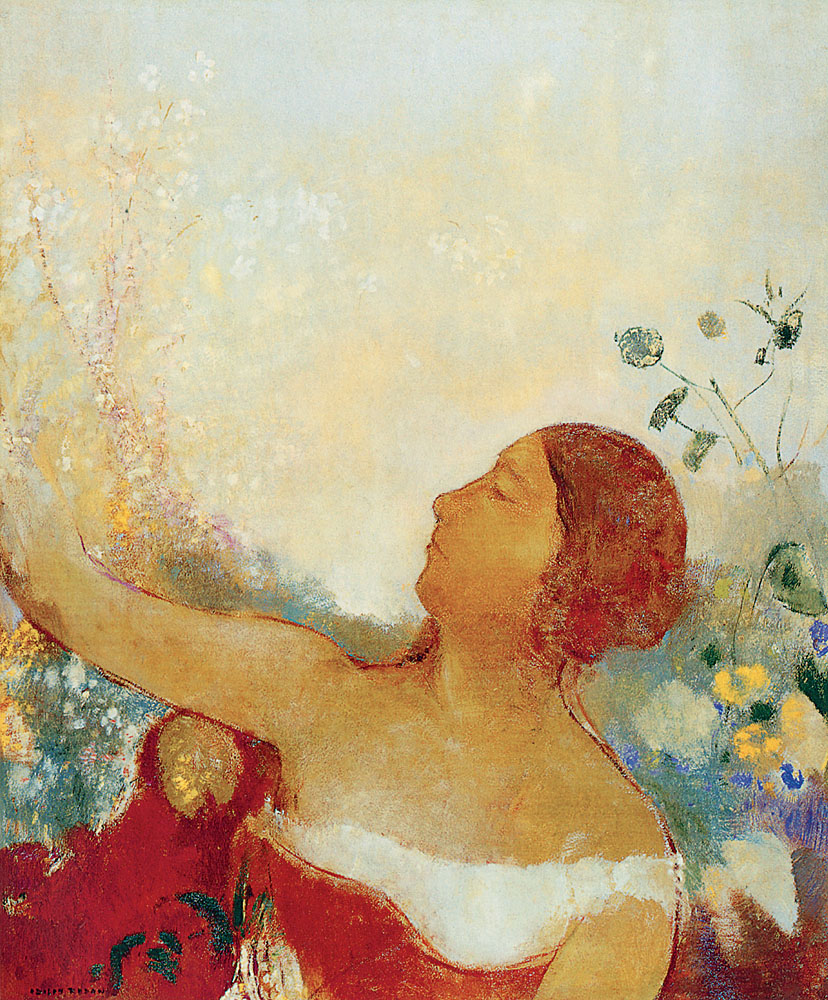

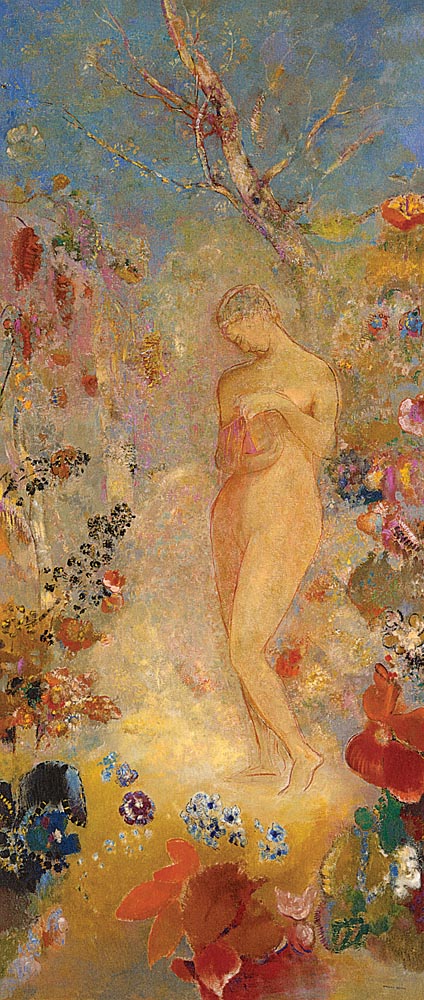

Woman with Flower Bodice, 1912

Pastel on coloured paper, 77.2 x 65.4 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Nearly all the Renaissance masterpieces have their origin in a literary idea, often also a philosophical idea, even the French painters. Art that is purely picturesque is inferior, and it is not without justice that Holland and Spain do not have the impact or prestige of Italian art.

Dimension. His relationship with the subject – We can see with the greatest masters an exuberance in manners they appear to be unaware of. Their strengths carry them too far; often they exceed the material limits in which they should frame their thoughts, the exaggeration they fall more easily into is an excessive dimension of the surface of painting and drawing. Before or after having found the exact measure for the representation of their subjects, or even whilst, it can happen that they go over, no point in restricting one’s self. It’s the genius proliferating and bearing abundant but less excellent fruits.

This is how it was for Dürer as he engraved those big paintings in wood that seemed to be destined for the decoration of apartments rather than books. Rembrandt, despite his etching genius, could not help but attempt much larger plates; and it is easy to judge how many of these are far from the perfection shining from his plates of ordinary dimension.

It is this way for painters, and all the more so, because in this art less limited than engravings, it is easy to let themselves be charmed by the taste of a large creation.

The most perfect works of art have been created in a dimension dictated by taste and reasoning; but these dimensions which a mediocre artist would adapt too easily seem to be for the most inspired artists more the result of chance than the result of conscience.

It would be interesting to find which artworks have been created in the desired dimensions and to see at which point they flourished for other painters.

For Bresdin, the same extravagance: he creates his drawings with a feather, but next to some beautiful works of art, we see some that may have benefited more being smaller. On stone, he does not control himself as much: in the great works, there is no relation between the fineness, the delicacy of detail and the surface of everything that the eye must take in.

It is infinitely more beautiful in the small lithography where his genius, essentially small and profound, rationally exerts itself and finds the emphases that is in accordance with the esthetic and visual order of his art.

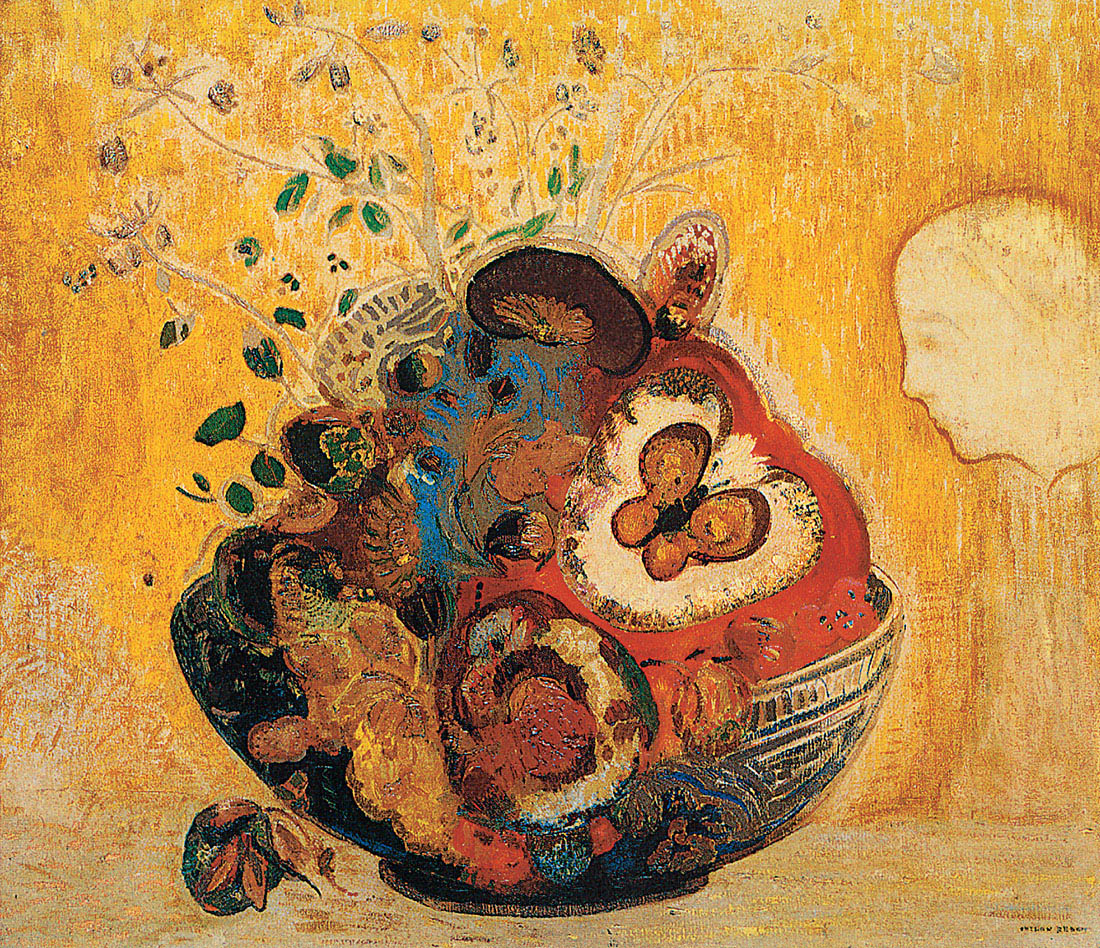

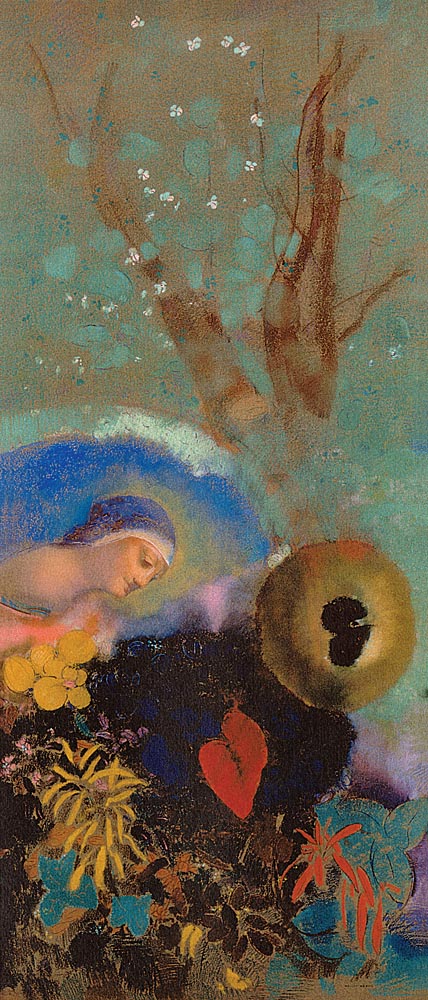

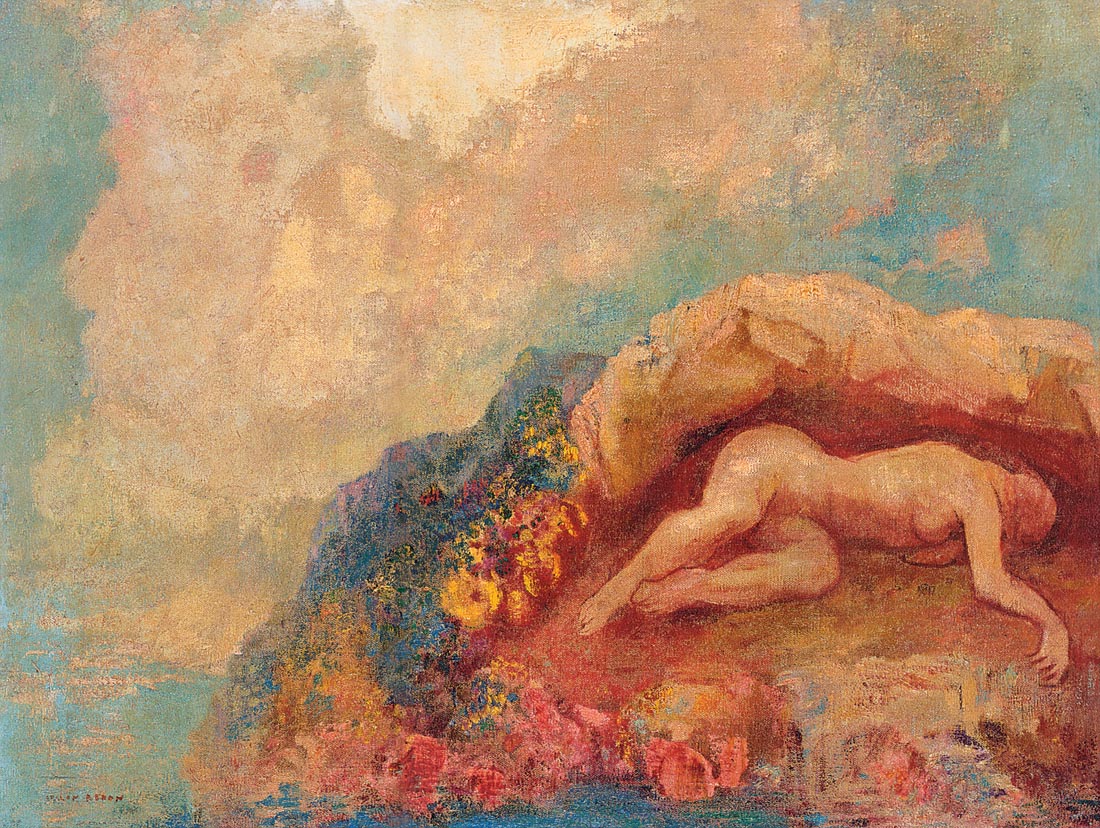

The Birth of Venus, c. 1912

Pastel, 84 x 65 cm. Petit Palais - Musée des Beaux-Arts de la ville de Paris, Paris