The Beginning of his Career

His Education

Rembrandt was born on 15 July 1606 in Leyden. No record of Rembrandt’s early youth has been discovered, but we may be sure that his religious instruction was the object of his mother’s special care, and that she strove to instil into her son the faith and moral principles that formed her own rule of life. The passages she read, the stories she recounted to him from her favourite book, made a deep and vivid impression on the child, and in later life he sought subjects for his works mainly in the sacred writings.

Leyden offered few facilities for an art student during that period. Painting, after a brief spell of splendour and activity, gave way to science and letters. Rembrandt’s parents considered him too young to leave them, and decided that his apprenticeship should be passed in his native home. An intimacy of long standing, and perhaps some tie of kinship, determined their choice of master.

They fixed upon an artist, Jacob van Swanenburch, now almost all but forgotten, though greatly esteemed by his contemporaries.

Though Rembrandt could learn little beyond the first principles of his art from such a teacher, he was treated by Swanenburch with a kindness not always met with by such youthful probationers. During Rembrandt’s three years in his trust, his progress was such that all fellow-citizens interested in his future “were amazed, and foresaw the glorious career that awaited him”.

His noviciate over, Rembrandt had nothing further to learn from Swanenburch. Now being old enough to leave his father’s house, his parents agreed that he should go forth and strengthen his skill in a more advanced art-centre. They chose Amsterdam and master Pieter Lastman, a very well-known painter at that time. In his studio, methods of instruction much akin to those adopted by Swanenburch were in vogue, though the personal talent modifying them was of a far higher order.

The Baptism of the Eunuch, 1626

Oil on wood, 63.5 x 78 cm. Rijksmuseum Het Catharijneconvent, Utrecht

Christ Driving the Moneychangers from the Temple, 1626

Oil on wood, 43 x 32 cm. The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

First Works Done in Leyden

The return of one so beloved by his family as Rembrandt was naturally hailed with joy in the home circle. But happy as he was to find himself thus welcomed, he had no intention of living idly under his father’s roof, and at once set resolutely to work. He had thrown off a yoke that had become irksome to him. Henceforth he had to seek guidance from himself alone, choosing his own path at his own risk. Amidst the evidence of youthful inexperience in these somewhat hasty works, we note details of great significance.

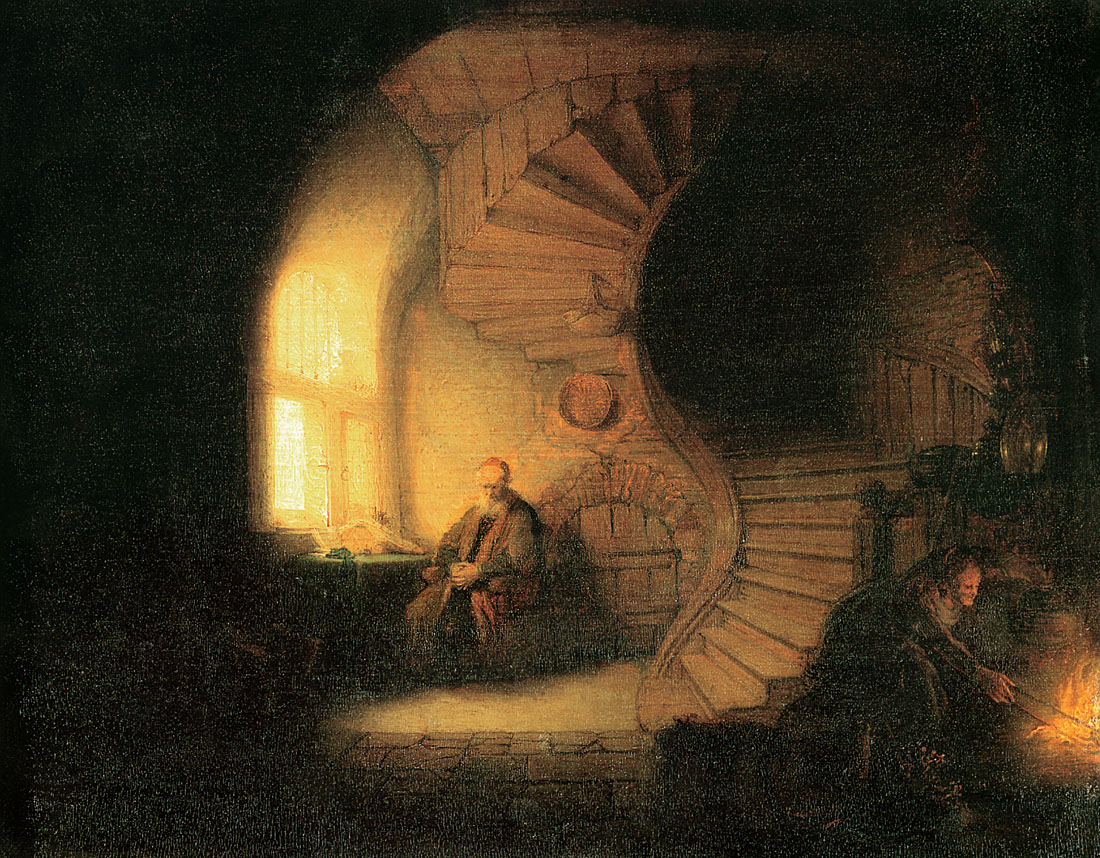

Saint Paul in Prison is dated 1627 and signed with his particular signature and monogram of that period. On examining the pale sunbeam, the serious countenance of the meditation, and Saint Paul pausing, pen in hand, to find the right expression for his thought, his earnest gaze and contemplative attitude, we recognise something beyond the conception of a commonplace beginner. We discern evidence of careful observation which Rembrandt in the full possession of his powers would have turned to higher account; but even with the imperfect means at his command, comes a striking effect. The patient and accurate execution of accessories such as the straw, the great iron sword, and the books by the apostle’s side, betokens a conscientious artist, who had applied to Nature for such help as she could give him.

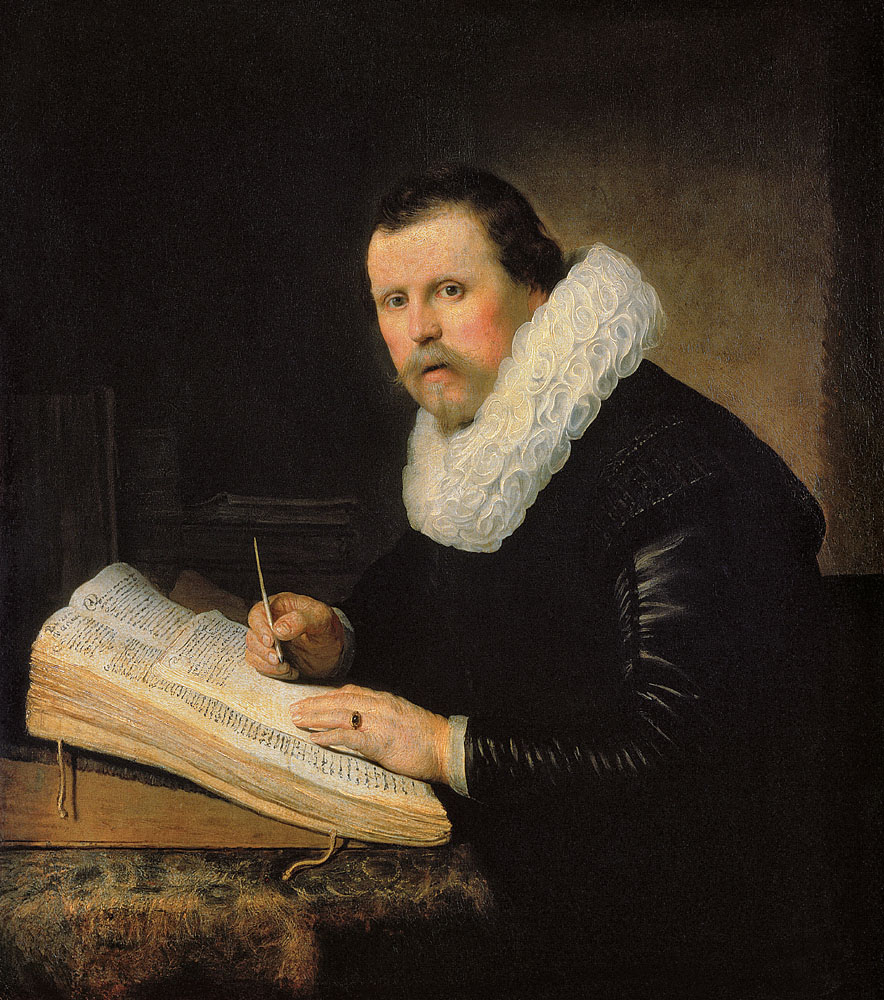

The Moneychanger (or The Parable of the Rich Man) bears the same date, 1627, with a monogram formed from the initials of the name “Rembrandt Harmensz”. An old man, seated at a table littered with parchments, ledgers, and money-bags, holds in his left hand a candle, the flame of which he shades with his right, and carefully examines a doubtful coin. Here the brushwork is somewhat heavy, and the piles of scrawled and dusty papers give an incoherent look to the composition. On the other hand, the light and the values are happily distributed and truthfully rendered. Rembrandt conceals the flame, and contents himself with rendering the light it sheds on surrounding objects. Restricting himself to such variety of light and shadow as may be won without the unpleasantness of violent contrasts, he concentrated all his powers on the delicate modelling of the old man’s head.

Rembrandt no longer confined himself to drawing and painting; his first etchings appeared in 1628, not much later than his first pictures. He took himself for a model in his etchings, and never tired of experimentation on his own person for purposes of study. It was a habit he retained throughout his career. With himself as his model, he felt even less restraint than when his relatives were his models, and this ensured an endless variety in his studies, and absolute freedom of fancy. Exact resemblance was not his aim in these works. They were studies rather than portraits. The diversity of emotion is studied from his own features: gaiety, terror, pain, sadness, concentration, satisfaction, and anger. Such experiments had, of course, their false and artificial aspects. Grimace rather than expression is suggested by many of these pensive airs, haggard eyes, affrighted looks, mouths wide with laughter, or contracted by pain. But in all such violent and factitious contrasts, Rembrandt sought the essential features of passions with great obvious effects, passions that stamp themselves plainly on the human face, and which the painter should, therefore, be able to render unmistakably. To this end, he forced expression to the verge of burlesque and, gradually correcting his deliberate exaggerations, he learnt to command the whole gamut of sentiment that lies between extremes, and to impress its various manifestations, from the deepest to the most transient, on the human face. The Baptism of the Eunuch was an incident greatly in favour with the painters of the day. It was a subject especially congenial to the Italianates; one in which they were able, under pretext of local colour, to heap on all the gorgeous accessories of the Oriental convention they loved. Rembrandt was no whit behind them in this respect; he even borrowed several details from his predecessors. The laborious care bestowed on the mise en scène is manifest in the splendid trappings of the chariot, the rich dresses of the servants, the attire of the convert and his guards, the rank luxuriance of gourds and thistles in the foreground. The sole elements of congruity are found in the saintly gravity of Philip and the reverent piety of the eunuch. We may add that he returns to the subject in 1641 for one of his etchings, in which he introduces several details of the earlier work. Without eliminating the fantastic element altogether, he successfully modifies the composition with a freer and more picturesque arrangement, and is careful to preserve the expressions of the apostle and the eunuch.

Landscape, as we have seen, plays but a secondary part in the works of Rembrandt so far. The picture in which it has figured most prominently hitherto is the Baptism of the Eunuch, where its feebleness certainly betrays the inadequacy of the master’s knowledge. The plants in the foreground are taken from separate studies of their various species, and grouped together in a manner far from convincing. They are excrescences in the composition, and add but little to its beauty. He never particularly distinguished himself in the painting of horses, but neither did he ever render them with such grotesque absurdity as in the Baptism of the Eunuch.

Simeon and Hannah in the Temple, c. 1627-1628

Oil on panel, 55.4 x 43.7 cm. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg

The Moneychanger (The Parable of the Rich Man), 1627

Oil on oak, 32 x 42.5 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

Bust of a Laughing Young Man, or Self-Portrait Laughing, c. 1628

Oil on wood, 41.2 x 33.8 cm. Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam

Saint Paul at his Desk, 1628-1629

Oil on wood, 47.2 x 38.6 cm. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg

Portrait of an Old Man Asleep, or Laziness, 1629

Oil on wood, 51.9 x 40.8 cm. Galleria Sabauda, Turin

Amsterdam

Leyden had become pre-eminently a city of scholars and theologians, in which Rembrandt could no longer hope for such encouragement as awaited him at Amsterdam. Though Rembrandt could paint pictures in his own studio for his patrons at Amsterdam, constant journeys back and forth were necessitated by his increasing practice as a portrait-painter. His friends in Amsterdam had long urged him to settle among them, and to this step he finally made up his mind either in the middle or towards the end of 1631.

By the year 1631, when Rembrandt took up his abode in the city, Amsterdam had risen to considerable importance. Rembrandt found facilities in his new residence that had been denied him in Leyden. Male models were procurable, and a few women sat for him.

In Rembrandt’s work as a whole we shall find him gaining steadily in breadth and freedom as his talent developed; yet we shall occasionally meet with examples bearing dates that seem almost incredible, taken in conjunction with other signed and dated works of the same year. Such anomalies may be variously explained. Many of his canvases remained for a long time in his studio, either because he delayed the finishing touches, or because purchasers were slow in making up their minds. In either case, he probably left them unsigned until finally disposing of them. Others were certainly re-painted, wholly or in part, and bear distinct traces of successive re-touching. Others again, though carried out more or less continuously, are very unequal in execution, the touch being in some parts minute and careful, in others bold and summary.

There is no obscurity of subject of the Rape of Proserpina. The theme here is apparent at a glance, though Rembrandt has disregarded all classical traditions in his treatment. It was probably painted around the same date as another picture, a Rape of Europa, to which it may have been a pendant dated 1632. The Proserpina, however, has great originality, both in conception and composition.

Rembrandt has turned the picturesque elements with which his imagination clothed the scene to the happiest account. A fine and appropriate effect is won by opposing the glowing sky and rich vegetation of the country to the darkness and desolation of the infernal regions. The contrast between the pale beauty of the victim and the strange features and brown skin of her future lord is no less marked. Two worlds seem to rise before the spectator, and each is characterised by the painter’s happy choice of its minutest details.

Mythology, with which Rembrandt so rarely succeeded, inspired him happily for once. Brushing aside established commonplace and decorative convention, he gave reality to the hackneyed legend. His inventive genius transfigured it, informing it with an indescribable vitality and fervour that lift us at once into the higher realms of poetry. In execution, the Rape of Proserpina is highly finished. The cool, almost cold, tonality is especially characteristic of this period.

Old Woman Praying (also known as Rembrandt’s Mother Praying), c. 1629-1630

Oil on copper, 15.5 x 12.2 cm. Residenzgalerie, Salzburg

Samson and Delilah, c. 1628

Oil on wood, 61.6 x 50.4 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

The numerous commissions that brought him to Amsterdam now occupied the greater part of his time. Portraiture had long enjoyed special favour in Holland. It had become in some measure a national speciality, to which the qualities of the Dutch school were peculiarly adapted. Their painters had excelled in this branch from the first dawn of art in the country. In his new home, Rembrandt had the opportunity to study, not only the best works of these masters, but a considerable number of portraits by Holbein, Van Dyck, Rubens, and the Italians, collected by rich amateurs. We may be sure that one so inquiring, so eager in the pursuit of knowledge, did not fail to profit by the advantages thus offered him.

Rembrandt’s sitters chiefly consisted of his own friends and relations. In working for strangers, he was forced to renounce those freaks of costume, attitude, and illumination in which he had formerly delighted, and to content himself with the habitual severity of Dutch dress and a close adherence to the living model. It was also necessary that he should learn something of the daily lives of those who relied on his genius for faithful transcripts of their diverse personalities.

One of the earliest portraits of this period is dated 1632, and in common with many works of this year bears the affix “Van Ryn”, after the well-known monogram. It is of small size, and the person represented seems commonplace enough on first inspection. This apparently austere personage was Maurice Huygens, Secretary to the Council of the States at the Hague, and brother of Constantine Huygens who professed such a great admiration for Rembrandt. Such a commission from a person of Maurice’s rank proves that Rembrandt’s reputation was already considerable.

We may further note a pair of large portraits of a man and his wife. In a pair of portraits painted around 1633, the arrangement of the two with a view to their mutual effect is even more obvious. The separate pictures seem to form one harmonious composition. The husband, a man of refined and distinguished appearance, is turned three quarters to the front. He seems to be speaking, and claims his wife’s attention by a gesture. She, stood near a table, looks lovingly towards him, and mutely acquiesces in his speech. Neither wife nor husband is remarkable for personal beauty, but the intelligent vivacity of the man’s face, the sweetness and affectionate confidence that beam from the dark eyes of his companion, and the devotion with which she listens to him, far from weakening the individual likeness, add the crowning touches of vitality. The young master, not content with a mere application of the technical skill he had acquired, was evidently anxious to produce a life-like and expressive work. He sought not to discard, but to rejuvenate tradition. He was already a painter of note when his great opportunity came with the Lesson in Anatomy, the work that was to proclaim the full measure of his genius and superiority over his rivals.

Rape of Proserpina, 1630

Oil on panel, 84.4 x 79.9 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem, 1630

Oil on panel, 58 x 46 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Resurrection of Lazarus, c. 1630

Oil on panel, 96.4 x 81.3 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

Old Man with a Gold Chain, c. 1631

Oil on panel, 83.1 x 75.7 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

A Dutch Painter

The Theatres of Anatomy

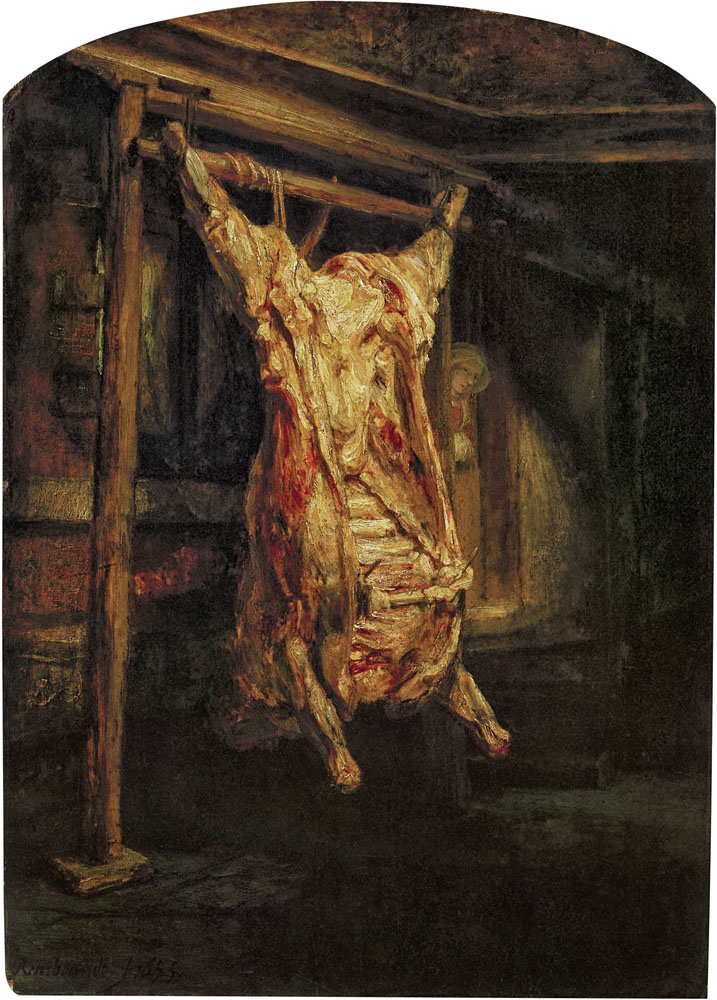

The study of medicine had long been held in peculiar honour among the Dutch, and its importance had greatly increased during the long warfare of the nation. The great diversity of wounds inflicted by fire-arms was the occasion of incessant research and progress in the domain of surgery; but such investigations could have no solid basis without a more extensive knowledge of the human frame than was then obtainable. Despite the impetus given to science by the Reformation, such study was jealously restricted for a long time to come. It was not until 1555 that Philip II agreed to authorise the dissection of corpses, and even then, such dissection was limited to the bodies of condemned criminals. It was violently opposed by the nation at large, the popular disapproval being mainly dictated by religious scruples based on the doctrine of the resurrection.

Gradually, however, those higher interests of humanity which were involved won the day, and dissections became more frequent. Among those who contributed most powerfully to this result was the famous Doctor Pieter Paauw, born in Amsterdam in 1564, who had returned from his travels eager to introduce into his own country the system he had seen at work in Italy.

From the moment that such experiments were legalised, physicians and surgeons fully recognised the value of the resources placed at their disposal, and the various anatomical preparations of which they made use in teaching, became the natural ornaments of their lecture halls.

These halls were fitted with concentric tiers of benches, with an open space in the middle for the professor, and a revolving table, on which the various objects necessary to his demonstration were placed before him. This arrangement, which was based on that of the theatres of Antiquity, gave rise to the term “theatre of anatomy”. Rembrandt had already seen one of these theatres at Leyden, the most famous then in existence.

Rembrandt, after his first successes as a portraitist, was called upon to try his strength in the beginning of 1632, when Dr Tulp commissioned him to paint the picture he wished to present to the Surgeons’ Guild, in memory of his professorship.

The main features of this work, now one of the gems of the Hague Museum, are familiar to all. It is also generally known that in signing it, the master discarded the monogram he had used before and wrote his name in full. Tulp, who wears a broad-brimmed felt hat, is seated in a vaulted hall at a dissecting-table, on which the corpse is laid obliquely. The professor holds up one of the tendons of the left arm with a pair of forceps, and seems to be enforcing his demonstration by a gesture of his left hand. Seven students, all men of mature age, are grouped to the right round the corpse, at whose feet lies a great open volume. Numbers are placed over their heads, and their names are inscribed in the following order on a paper held by one of them: 1. Tulp, 2. Jacob Blok, 3. Hartman Hartmansz, 4. Adriaen Slabran, 5. Jacob de Witt, 6. Mathys Kalkoen, 7. Jacob Koolvelt, 8. Frans van Loenen. The figures, painted life-size and three quarters length are illuminated by a soft light from the left, which is concentrated on the corpse, on the heads of the two seated auditors in the foreground, and on the face of Tulp, whose calm attitude, air of authority, and expression of confident intelligence at once rivet attention.

We shall find many beauties to admire; foremost among them the figure of Tulp, with its happy simplicity of pose, its decision and vigour of expression, and the intelligent faces of the two disciples nearest the master, who hang upon every word, gazing intently at him and endeavouring to penetrate his innermost thought. But the composition in its entirety is more striking than any of these fragmentary excellences. It is remarkable for the sobriety of the details, their perfect subordination, and the elimination of all such as by their puerility or vulgarity might impair the gravity of the subject. The arrangement of the masses appeals alike to the eye and the mind of the spectator, bringing out the essential features in strong relief: on the one side the listeners in a compact group; the corpse, the object of their common studies, between them and the professor; and Tulp himself, placed, like the corpse, in a strong light, but apart from the rest. The attention of the spectator is directed to him by the convergence of the principal lines, by the concentration of all eyes upon him, and finally by his own commanding gesture and authoritative mien. In these respects it must be conceded that Rembrandt fully carried out the proposed conditions of his undertaking. Popular instinct has not been at fault in this case, and the public, while neglecting previous works of this class, or studying them merely as documents, continues to rank Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson among those typical achievements which sum up and annihilate previous efforts. It will be no overstatement of its historical importance to say that it forms an epoch, not only in Rembrandt’s career, but in the art of his country. For this work consecrated the Dutch ideal, as it were, and awoke in the Dutch school a consciousness of its own strength, exhorting it to persevere in its chosen course; such art was in harmony with its tastes, its love of truth, its conscientious precision, its hankering after perfect technique. But Rembrandt, at every fresh essay in the treatment of contemporary themes, enlarged their horizons and touched them with new life.

The poetry with which he thus informed the national art had nothing in common with the traditions of his first masters, who were very much influenced by the Italians.

Rembrandt’s Mother as Biblical Prophetess Hannah, 1631

Oil on panel, 60 x 48 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Man in Oriental Costume (“The Noble Slav”), 1632

Oil on canvas, 152.7 x 111.1 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Adoration of the Magi, 1632

Oil on paper pasted on canvas, 45 x 39 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, 1632

Oil on canvas, 169.5 x 216.5 cm. Mauritshuis, The Hague

Susanna van Collen, Wife of Jean Pellicorne with her Daughter Anna, c. 1632

Oil on canvas, 155.3 x 122.5 cm. The Wallace Collection, London

A Lady and Gentleman in Black, 1633

Oil on canvas, 131.6 x 109 cm. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (Painting stolen in 1990)

Achievements

The success of the Anatomy Lesson was brilliant. Rembrandt’s name, already well-known in Amsterdam, now became famous. His rank among the first living painters was assured, and commissions flowed in rapidly. In 1632 he had ten in hand, and from 1632 to 1634 at least forty. His manner became broader, though he abated nothing of the sincerity and conscientious care that spawned his reputation. He enlarged, without substantially altering his style. The execution of his first large canvas had made him sensible of certain deficiencies in freedom and breadth of conception and vigour of drawing.

The year 1633 was such a prolific one that we must be content with a brief mention of the various family and individual portraits. A more important work on this small scale is the full-length portrait of a young couple in a room, about one third of life-size, signed, and dated 1633. The husband, a man of rather thickset figure, stands beside his young wife, who is seated to the left. Both are evidently in high good humour, and neither their faces nor attitudes betray the discomfort of their posture. But it seems that the master, who had inclined to works of this size at the beginning of his career, now began to feel oppressed by their restricted dimensions. He required a larger field for the exercise of his newly acquired qualities. He holds his own by virtue of his superior knowledge of chiaroscuro and deeper insight into character, but he has more than one rival.

Rembrandt’s great masterpiece of 1633, a year so rich in important works, is the large canvas known as Portrait of Jan Rijcksen and his Wife, Griet Jans (“The Shipbuilder and his Wife”). Both husband and wife are very simply dressed, and all the details of their modest dwelling indicate an orderly life of mutual affection, honourably maintained by the labours of the old man and the good management of the woman who looks at him with so cordial a smile. Rembrandt seems to have been touched by their tender affection, so sympathetic is his rendering of its moral beauty and serene pathos. The frank and generous execution, the soft warm light, the sober colour, the transparent shadows, are all in exquisite harmony with the homely scene, and attune the spectator’s mind to fuller sympathy with the old couple. The idea of painting husband and wife, and even the several members of a family, on the same canvas was not, of course, a novel one. But here the young artist outstripped both predecessors and rivals. Increasing the scale, he used each figure to complete the truth and individuality of the other. By bringing them thus together, he has given us not merely a picture, but an epitome of two lives, which, thanks to his art, are as closely associated in our memories as in reality.

Portrait of a Bearded Man in a Wide-Brimmed Hat, 1633

Oil on panel, 69.9 x 54.6 cm. Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena

Saskia, 1633

Oil on oak, 52.4 x 44 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister,

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Dresden

Portrait of Jan Rijcksen and his Wife, Griet Jans (“The Shipbuilder and his Wife”), 1633

Oil on canvas, 113.3 x 169.4 cm. The Royal Collection, London

A Healthy Business

At this juncture, when Rembrandt’s growing fame was bringing him increasingly to public notice, his successes were crowned by a series of important purchases and commissions made on behalf of the Prince, Frederick Henry, who, under the title of Stathouder, then governed Holland, and whose name will be lastingly associated with its supreme period of prosperity. Constantine Huygens, his secretary, acted as intermediary in his transactions with artists. Several letters exchanged between Rembrandt and Huygens give some interesting information in connection with a series of compositions bought at various intervals by the Stathouder.

In 1633, Rembrandt had two of the finished works in his studio: the Elevation of the Cross and the Descent from the Cross. The opening letter of the correspondence doubtless refers to these. One of them had taken the Stathouder’s fancy, and he had announced his intention of buying it.

In the Descent from the Cross, the body of Christ has just been detached; His head, convulsed with agony, falls upon His shoulder. A man, leaning over one of the arms of the cross, holds up the winding-sheet on which four people standing below support the body. The precious burden, drooping, mangled and inert, is received with tender respect. On the ground below, the disciples and the holy women arrange the draperies for His burial, or press forward to aid the Virgin, who falls fainting into the arms of Mary Magdalene. A man with a grey beard, in a turban, looks on callously at the pathetic scene, his indifference emphasising the emotion of those around him. Though the picture is carefully executed and elaborately finished, we detect various hesitations and corrections. A very evident pentamento shows that the two upper figures on either side of Christ were originally rather higher up.

The Prince’s purchases were not confined to these two pictures. He was doubtless pleased with his acquisition, for a letter written by Rembrandt in February 1636, informs us that “Frederick Henry had commissioned the painter to produce three other works, an Entombment, a Resurrection, and an Ascension, uniform with the Elevation of the Cross, and the Descent from the Cross” already received by the Stathouder. It seems probable that the Ascension was straightway delivered, and that the two remaining canvases were not handed over to the Prince until three years later.

The last two pictures of the series, the Entombment and the Resurrection, were not completed until 1639. Rembrandt had carried them out with great care and diligence and had endeavoured to make these the most vigorous and natural of the series, which is the main reason why he had had them so long in hand.

Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633

Oil on canvas, 160 x 128 cm. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Portrait of Johannes Wtenbogaert (1557-1644), Remonstrant Minister, 1633

Oil on canvas, 130 x 103 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Meeting Saskia

Among the portraits of 1632 is an oval on canvas that represents a young girl, her face in profile, and turned to the left. The forehead is somewhat prominent, the nose straight and small, but thickening slightly towards the end, the mouth very dainty, the face rather full, with a hint of an approaching double chin, the small eyes rather heavily lidded. These irregular and by no means remarkable features are glorified by a brilliant complexion, and fair hair waving over the forehead in charming disorder. The costume is remarkable for its elegant simplicity, and the execution, agreeing with the attitude and expression, is irreproachably correct and demure. This young girl, whose features we shall recognise in many works painted during the nine years of life that remained to her, was Saskia van Uylenborch, who was shortly to become Rembrandt’s bride.

We believe Saskia to be the original of another work, signed and dated around 1665/1666, which was famous at the end of the last century as The Jewish Bride. Seated, and almost facing the spectator, the young woman wears a white satin dress embroidered with gold and over it the heavy crimson mantle we have already pointed out in several pictures of this period. An old woman stands behind her, combing her long fair hair. The figures are relieved by an architectural background of warm grey, which brings out the reds of the drapery, and the cool carnations. A low bench and a candelabrum are just distinguishable against the wall. The face and hands of the young woman are exquisitely modelled in very high tones, and the learned precision of touch, and transparent delicacy of the chiaroscuro make this labour of love one of the most important, as it is certainly one of the best preserved works inspired by Saskia at this period.

Rembrandt’s numerous portraits of Saskia, and his attentions to members of her family, proclaim the feelings with which the young girl had inspired him. Up to this date the young painter had lived a very retired life in Amsterdam; he had no taste for the amusements that pleased his brother artists, and was never to be met with in any of the taverns or other haunts frequented by them. A man with such habits and with Rembrandt’s loving disposition must have longed for a home of his own; his thoughts naturally turned to marriage. His meeting with the gentle, well-born girl was not without results. She, he felt, was the mate for him. He accordingly embosomed himself to the Sylviuses, her guardians. In a family which, though mainly composed of ministers and lawyers, already reckoned several artists among its members, no prejudice was likely to be felt against his calling.

In the marriage register of Amsterdam, under the date 10 June 1634, we find the declaration made before the commissaries by the preacher Jan Cornells Sylvius, who, as Saskia’s cousin, pledges himself on her behalf to give his formal consent to the marriage before the third publication of the banns. On his side, Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, of Leyden, aged twenty-six years and residing in the Breestraat, engaged to produce his mother’s consent in due course, and triumphantly added the signature.

Among the works of this period, many more important than these were also inspired by Saskia. Rembrandt, we know, did not wait until after his marriage to deck her out according to his fancy. But now that she had become his housemate, he brought out all the treasures of his wardrobes to vary her attire. For the next few years, she was his most frequent model, and the greater number of his pictures were directly or indirectly suggested by her. Just as in earlier days he had made use of himself and of the various members of his family for his studies, he now took full advantage of the complaisant model by his side.

In their happy solitude, forgetful of the outside world, and free from all restraints, the newly married pair found their pleasure, like children, in the merest trifles. Each day some fresh farce and amusement was devised, some feast or comedy, where each entertained the other, and where they themselves were the sole guests and actors. But even on days like these, the painter could not be idle. He has immortalised one of these innocent orgies in the famous picture of the Dresden Gallery, where he has painted himself, with Saskia sitting on his knees. The artist is seated in a chair, dressed in a military costume and brandishes a long glass of sparkling wine in his right hand. With his left, he clasps his wife’s waist. Saskia wears a rich, but somewhat fantastic dress. Her sweet, fresh face is turned towards the spectator. Rembrandt, whose eyes are slightly misty, laughs aloud, displaying both rows of teeth, and shakes his flowing hair. Saskia’s face looks smaller than ever beside his great head; she might be a fairy in the grasp of a giant, confident of her own power, trustful and happy in the love she has inspired. Her expression is calm, and she seems rather astonished than amused; the faintest suspicion of a smile hovers about her lips. As to the master himself, his noisy gaiety is rather forced; the part he plays seems to involve a certain degree of effort. It is evident that such junketings are not usual with him; that he is a man of sober habits, attracted by the picturesque aspect of the scene, rather than by its appeal to gluttony and sensuality.

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1634

Oil on wood, 53.1 x 50.5 cm. The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Judith at the Banquet of Holofernes, 1634

Oil on canvas, 143 x 154.7 cm. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume, 1635

Oil on canvas, 123.5 x 97.5 cm. The National Gallery, London

Samson Accusing his Father-in-Law, 1635

Oil on canvas, 159.7 x 131 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

Self-Portrait with Saskia, or The Prodigal Son in the Tavern, or The Allegory of Love and Wine, c. 1635

Oil on canvas, 161 x 131 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Dresden

The Blinding of Samson, 1636

Oil on canvas, 206 x 276 cm. Städel Museum, Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am Main

Success

The Beginning of Fame

When free to choose his own themes, Rembrandt drew his inspiration mainly from the Scriptures, to him the source alike of the loftiest, and of the most purely human sentiments. Fired by his study of the sacred page, his imagination evoked the episodes he proposed to treat and marshalled them before his eyes. He then set himself primarily to bring out their most characteristic features.

Abraham’s Sacrifice was one of the Biblical episodes most affected by the Italianates. This was the point in the drama which also appealed to Rembrandt, not only as the most impressive, but as lending itself most readily to those effects of chiaroscuro which had such fascination for him. The life-size picture in the Hermitage, inspired by this episode and painted in 1635, is among his most important works. The composition is extremely striking. In the foreground, Isaac is stretched almost naked at his father’s feet. The transparent softness of the half-tones on the angel’s face, and on the lad’s bare legs, the skilful modelling of the naked body, the building up of the high lights, and the delicate flexibility with which they follow the play of the surfaces, the high-toned harmony of the draperies, and the fresh, cool tints of which pale greens, pearly greys, subdued blues and yellows which recall those of The Jewish Bride of 1634 hanging close by, are all characteristic notes of this period. We may further mark the scrupulous study of nature evinced in details such as the angel’s wings, which the master has painted from the tawny plumage of some bird of prey. Carefully as these details are rendered, however, they are no mere servile reproductions. In his interpretations of nature, Rembrandt keeps the exigencies of his own conception steadily in view. His progress is very marked in this respect. During the summer of 1635, Saskia visited her relations in Friesland, and on 12 July, she was present at the baptism of a child of Hiskia’s. The visit, however, must have been a brief one, for Saskia was herself about to become a mother. Her first child was a boy, who was baptised Rombertus, after his maternal grandfather, in the Oude-Kerk of Amsterdam, 15 December 1635. The advent of his first-born must have filled Rembrandt’s heart with feelings hitherto unknown. He was able to watch the awakening of life in the little creature, and to study its movements in all their expressive helplessness. He did not fail to take advantage of the tiny model, and made innumerable drawings of its attitudes and gestures. Many sketches from nature which probably belong to this period show the child in various aspects of its baby life. We see it pressing against its nurse’s bosom, and feeding with gluttonous delight, or stiff and replete in its tight swaddling-clothes, kicking merrily before a blazing fire, or sound asleep.

Rembrandt had now more time at his disposal. His marriage and the proceeds of his portraits ensured him a certain income, and he felt himself free to pursue these methods of study. Many of the figures he collected were used at this period in compositions inspired, as usual, by the sacred writings. Among such compositions is a small picture in the Pushkin Museum, dated 1634, representing The Incredulity of St Thomas. The scene is well arranged, and the colour is not without brilliance. But the handling is timid, awkward, and wanting in breadth, while the cold colour, blue or greenish in tone, to which the master sometimes had recourse at this period, has none of the richness and distinction that mark many of his contemporary works.

Belshazzar’s Feast probably dates from about the same period. Rembrandt was doubtless fascinated, not only by the decorative splendour proper to such a theme, but by the opportunities it afforded for contrasts of chiaroscuro. The master, as may be supposed, was fully alive to the effect to be won from the display of glittering plate on the table, and the luminous writing on the wall confronting the terror-stricken king. But the coarse handling gives an exaggerated appearance to the contrasts, and the awe of some among the company is expressed by mere grimace. All the defects of this work are intensified in a large canvas dated 1636, The Blinding of Samson. The scene is at once horrible and grotesque; the painter seems to have revelled in the repulsive aspects of his subject, and its offensiveness is enhanced by the large scale of the work, the figures being nearly life-size. In spite of the shock produced by the accumulation of horrors, we are impressed by the elements of wild grandeur and ferocity that characterise the scene.

Saskia’s features are more clearly recognisable in two studies of Susanna and the Elders, one dated 1637, the other dated 1647. In the second one, a young woman of Saskia’s figure and features is represented almost naked. She has thrown off her garments, a purple robe trimmed with gold and a white chemisette with embroidered sleeves, and is about to step into a bath, above which rise the branches of tall trees, and a palace, the walls of which stand out in relief against a dark sky. A rustling in the foliage startles her as she is about to cast aside the last of her draperies, and turning her rosy face in alarm towards the spectator, she modestly endeavours to hide her nakedness. Behind her, in a tangle of plants and foliage, two heads are slightly indicated, one with gleaming eyes, the other in a turban with a plume. The strong tones of the vegetation, the sky, and the building, emphasise the whiteness of the somewhat thickset figure. The composition, and the gesture of Susanna, seem to have taken Rembrandt’s fancy; we shall find him reproducing the episode, with very slight modifications, in a later work.

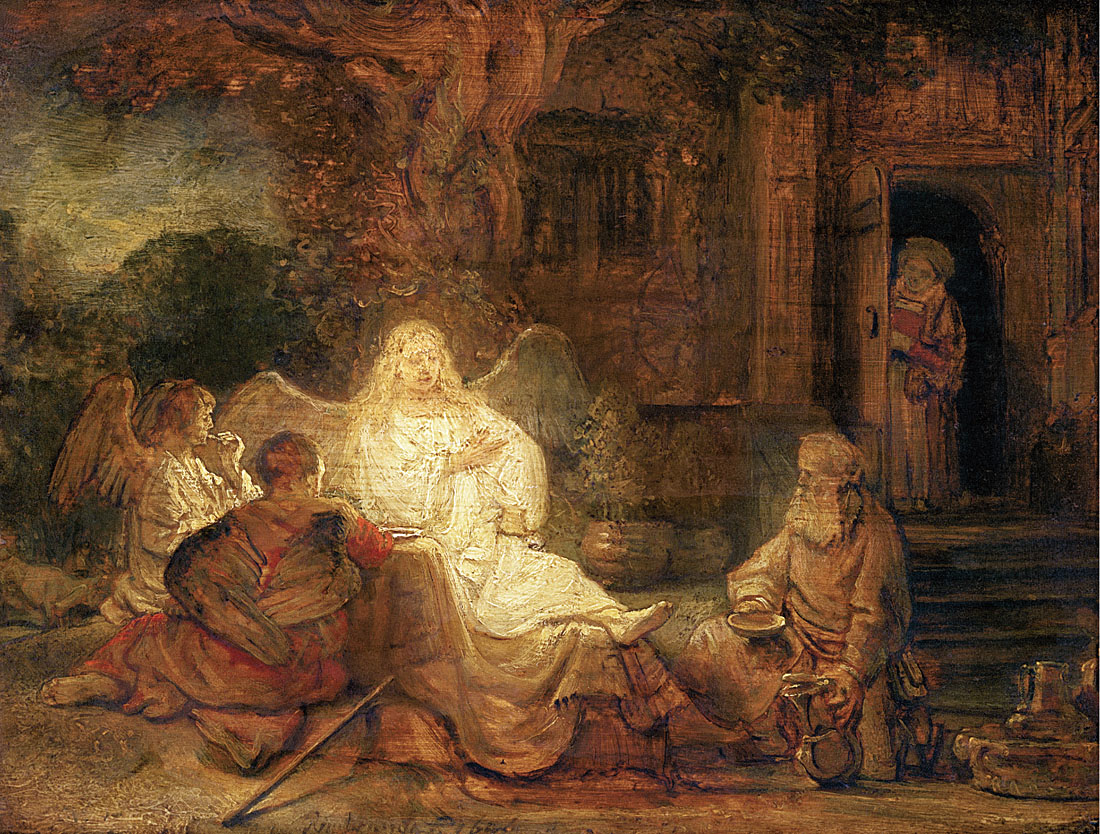

The Angel Raphael Leaving Tobias, in the Louvre, signed and dated 1637, is unquestionably one of Rembrandt’s masterpieces. The moment chosen by the master is that in which the Angel, his mission accomplished, reveals himself to the family at the threshold of their dwelling, and takes flight. The simplicity and originality of the composition, the ingenious device by which the master concentrates his group towards the left, yet contrives to draw attention to the Angel by the flow of the lines, and the looks and gestures of the persons below. The flashing radiance of the ascending figure, with its floating hair and draperies, the beautiful adjustment of the pale blue dress over the white tunic, the nervous grace of the iridescent wings, the contrast of their brilliant tints with the sober, yet vigorous tonality of the whole; greys, yellows, greens, and russets on an amber ground, forming a golden brown harmony; from a distance, the expression of the faces, each exactly attuned to the age and character of the actor the austerity of the landscape, and the execution, sober, animated, facile, and insistent only in the most important passages – all these qualities combine to make the work one of the most original and complete of the master’s creations.

The Angel Raphael Leaving the Family of Tobias, 1637

Oil on wood, 66 x 52 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Concord of the State, c. 1637-1645

Oil on wood, 74.6 x 101 cm. Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Christ and St Mary Magdalene at the Tomb, 1638

Oil on panel, 61 x 49.5 cm. The Royal Collection, London

Rembrandt’s Reputation and Saskia’s Illness

Rembrandt was often accused of avarice; however, few artists have actually shown an equal lack of worldly wisdom regarding their financial affairs, a lack of wisdom from which he cruelly suffered at the end of his career. He squandered his money in the most reckless manner, including that which Saskia brought him, no less than his own earnings, and the inheritances that fell to him from time to time. As his money came in, it was immediately spent on acquisitions of all sorts. He also drew largely on his credit: regarding ornaments for his beloved Saskia, nothing was too magnificent.

Unhappily, Saskia’s health had given Rembrandt great cause for anxiety for some time. Her strength had been severely taxed by the birth of several children. She had lost her eldest son, who was born at the end of 1635. A daughter, born on 1 July 1638, was baptised Cornelia, after Rembrandt’s mother, at the Oude Kerk on 22 July of the following year. However, this child also died, on 29 July 1640.

After the death of his mother, Rembrandt naturally sought solace and distraction in his work and the affections that remained with him. Thus, as may be readily imagined, seeing how intimate the union between his life and art had always been, his works of this period faithfully reflect the thoughts that filled his mind. The subjects that attracted him are all closely allied to his most intimate musings. They are chiefly scenes of family life, in which he seeks to express, even more deeply than before, the joys dearer to him than ever now that his mother’s death and Saskia’s failing health made him understand their impermanence. The Carpenter’s Household, signed and dated 1640, is one of the best among the small pictures painted by Rembrandt at this date. The composition is extremely simple. The meticulous finish, delicate style, and radiant aspects both of life and nature shedding luster in this work, seem to suggest that the painter had put forth all his powers to express this poetic conception of work and family life, the two things dearest to him.

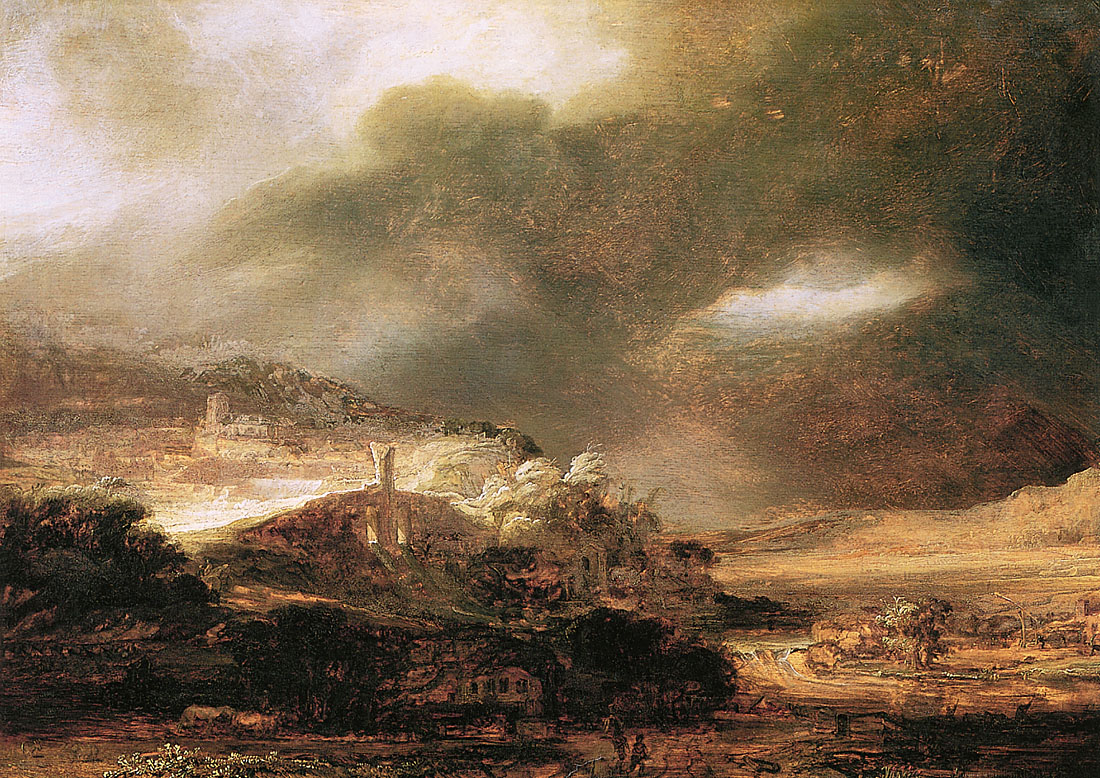

Landscape with an Obelisk, 1638

Oil on wood panel, 54.5 x 71 cm. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

The Entombment, c. 1639

Oil on oak panel, 32.2 x 40.5 cm. Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow

Self-Portrait at the Age of Thirty-Four, 1640

Oil on canvas, 102 x 80 cm. The National Gallery, London

Portrait of Baertje Martens, c. 1640

Oil on wood panel (oak), 76 x 56 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The Night Watch

The first portrait groups of civic guards were composed on much the same lines as those of religious associations. In all, the arrangement is practically identical, but the artists make an attempt to put some sort of animation into the faces of their sitters, and to diversify the accessories in their hands. Very few among them attempted to modify the traditional treatment, and the timidity of their efforts, or the feebleness of their powers, rendered all such essays abortive. It had never occurred to any of them to represent the companies engaged in any of those military exercises which were the sole objects of their formation.

Such a conception was reserved for Rembrandt, when he, in his turn, received a commission to paint a large picture for the newly erected Hall of the Amsterdam Musketeers. Rembrandt, we know, was not the man to bow his neck to the yoke of accepted tradition, or to yield to the exactions that had hampered former painters of such compositions. He claimed absolute liberty.

The proposed originality of treatment, coupled with the name of Rembrandt, ensured the notoriety of a work in which the captain of the company was to occupy the most prominent place. In consideration of the painter’s reputation, he was offered 1600 florins in payment, a sum greatly in excess of any previously received for such works.

The erroneous title of The Night Watch, by which the picture is traditionally known, may be disregarded; the true designation is appended to a watercolour sketch of the composition, made between 1650 and 1660 for an album belonging to Banning Cocq himself. This sketch still remains in the family of its original owner, and is inscribed: “The young Lord of Purmerland gives the order to march to his lieutenant, Heer van Vlaerdingen.”

The composition agrees on every point with the idea it suggests, and there is no room for doubt as to the theme. But fault has been found with the work on another score. It has been pointed out that the canvas is crowded to excess; that it affords no rest for the eye, and has the appearance of being imprisoned by the frame. The feet of the two officers touch the edge in the centre; the drum on the right, the child who is running, and the man seated on the parapet to the left are cut in two by the frame. The effect of this is extremely startling and unpleasant. The composition has no definite limits, and instead of gradually melting away, as it were, is suddenly cut short at either end. But for these undeniable blemishes the master is in no wise accountable. They are due, not to Rembrandt, but to those who mutilated his creation. The fact of these mutilations has been completely established.

We learnt from archival documents that The Night Watch was placed in the Hall of the Musketeers’ Doelen in 1642, and was eventually moved to the Town Hall of Amsterdam. It was then that the mutilation, which a contemporary picture-restorer has recorded, took place. J. van Dyck, in his description of the pictures in the Amsterdam Town Hall, remarked that, in order to suit the picture to the dimensions of its appointed place between the two doors of the small council-chamber, “it was found necessary to cut off two figures to the right of the canvas, and part of the drum to the left, as may be seen by comparison of the original with the copy in Heer Boendermaker’s possession”. Barbarous as such a proceeding appears to us, it was very lightly regarded in the last century. Collectors and dealers occasionally cut up pictures, making two or more out of one, and it is not unusual to find works in public galleries or private collections, the original dimensions of which have been modified, either to accommodate them to some particular space, or merely to make them fit some frame in the owner’s possession.

Other blemishes are entirely the result of injuries sustained by the picture in the course of years. Very little care was bestowed on works of art in the Doelens, which were practically tap-rooms. Tobacco-smoke and the fumes from peat-fires soon blackened the pictures on the walls. They were re-varnished from time to time, but the accumulated dirt was never properly removed, and was therefore firmly embedded in the successive strata. Its appearance at this time fully accounted for the title The Night Watch, bestowed upon it during the 18th century. The darkness that was gradually invading the canvas seemed to justify the misnomer.

The restoration of the picture was long delayed, owing to the difficulties of the undertaking. The superficial stratum of oil and varnish, which had become rough and opaque, was rubbed down; it was then made transparent by exposing the canvas to the fumes of cold alcohol. The picture regained its pristine brilliance, to the astonishment of those most familiar with it. It is now evident enough that Rembrandt painted the scene in sunlight. There is not the slightest indication of artificial light, and it is even possible to deduce the exact position of the sun at the moment, from the shadow cast by Banning Cocq’s hand on his lieutenant’s tunic.

The Night Watch holds a place apart in the history of corporation pictures by virtue of its originality and the treatment and beauty of its execution. It was reserved for Rembrandt, in his first attempt in this genre, to recognise the true conditions of such a class of pictures. As ten years before in the Anatomy Lesson, and twenty years later in the Sampling Officials, he now distanced himself from his rivals. Like them, he had been content to express his meaning plainly, without the help of allegory; but he had brushed aside all the conventions in which they were gradually entangled.

The Night Watch was finished in the earlier part of 1642. The year before, the happiness of Rembrandt and his wife had been crowned by the birth of a son. He was baptised in the Zuider Kerk, 22 September 1641, by the name of Titus, in memory of Saskia’s sister Titia, who died on 16 June of the same year.

The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch known as The Night Watch, 1642

Oil on canvas, 379.5 x 453.5 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Young Woman Leaning on a Stone Support, 1645

Oil on canvas, 81.6 x 66 cm. Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

Saskia’s Death

Less than a year after the birth of Titus, Saskia’s illness reached a stage at which illusions about her recovery were no longer possible. Feeling herself to be growing gradually weaker, she begged that a notary be brought to her bedside, and on 5 June 1642, at nine o’clock in the morning, “in full possession of all her faculties”, she gave him her last instructions in the presence of two witnesses.

A few days later Saskia had passed away, and on 19 June, Rembrandt, after following her coffin to the Oude Kerk, returned to the house in the Breestraat, where he now found himself alone with a child of nine months.

The loss of a wife he had dearly loved was not Rembrandt’s only trouble at this period. He saw that his popularity was waning. He, who had been the most fashionable and the most famous of Dutch painters, was beginning to experience neglect. His eccentric attitude towards the distinguished society who had received him so warmly at first had estranged many from him. The Night Watch was destined to deal a fatal blow to his reputation, and diminish his clientele. Those more immediately concerned in the matter naturally resented so audacious a divergence from traditional ideas.

Rembrandt’s work was not only a heresy in their eyes, it was little short of disrespect. Relying on orthodox precedents, each subject had paid for a good likeness of himself and a good place on the canvas. But the painter boldly ignored the terms of the tacit contract. The two officers prominent in the centre of the composition had, of course, nothing to complain about, and Banning Cocq himself seems to have been satisfied, or he would hardly have ordered the watercolour copy of The Night Watch already mentioned. But the rank and file, with the exception of some four or five members, had come off very badly, and from their point of view these worthy folks had a distinct grievance against the master. Knowing Rembrandt’s character, we can imagine that he met their representations with scanty respect, and so increased their resentment. As he could not be induced to alter the picture, his outraged models took refuge in the only consolation they had left. Failing their likenesses, they determined at least to preserve their names, and these were accordingly inscribed on a shield painted on the upper part of the canvas. The careless treatment of the painting and the mutilation to which it was subjected seem to show that Rembrandt’s contemporaries long cherished their resentment against him. After such a blow to their vanity the civic guards bestowed their patronage elsewhere. His commissions fell off gradually from this time forward. Adversity, far from softening his character, gave a misanthropic tinge to a disposition naturally somewhat morose. He had still a few faithful friends whose affection sustained him through his sufferings, but now, as ever, he found art his best consolation. For a time he was been utterly crushed by the overwhelming sorrow of his loss, but as he became calmer he turned eagerly to work and sought refuge from solitude in occupation.

Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, 1653

Oil on canvas, 143.5 x 136.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

His thoughts turned naturally to the Scriptures. At this season of deep emotion, he sought comfort in his favourite book, and chose, among its countless episodes, those best attuned to his frame of mind. In the Holy Family, which was painted in this period, he gave utterance to his regrets. The handling is broad and free, but the colour has been very much darkened by the brown varnish overlying it. The composition has nothing of the sublime; such a picture, with its somewhat vulgar types, would be out of place over an altar. But we must remember that it was painted for a Dutch home, and its glorification of toil and maternity responded to the ideals of the age and nation. Here Rembrandt cast off the trammels of the text, enlarging and modernising the theme. Even in painting a humble scene of everyday life such as this, he keeps the eternal truths of the spiritual life in view. In this masterpiece of tender expression, every detail charms and touches the sleeping child, the attitude and gesture of the mother, the sweet emotion of her gaze, and the peaceful atmosphere of the scene.

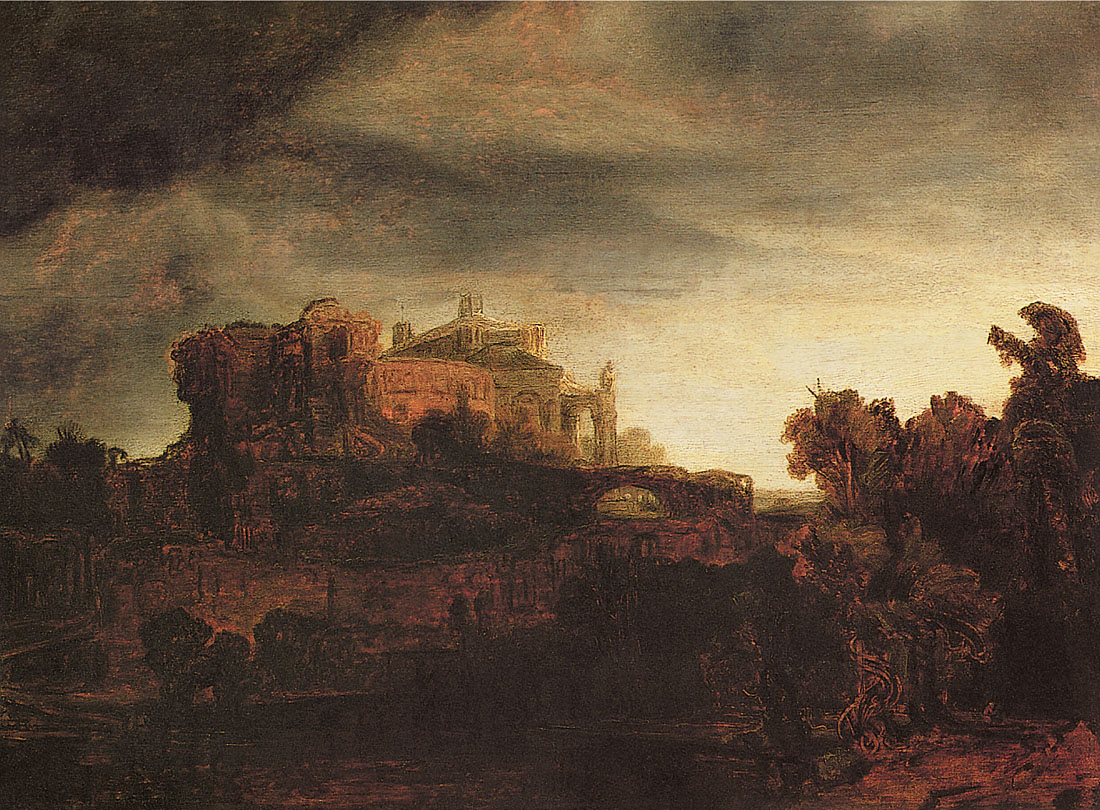

From this time forth he recognised how infinite the resources offered him by nature were for the expression of his thought, and gradually landscape played an increasingly important part in his works, as we notice in the Rape of Proserpina in the Gemäldegalerie of Berlin. Even in his pure landscapes of this period, convention takes the place of direct observation, and the painter’s reliance on an accepted ideal is very apparent. Simplicity is openly disregarded in these early attempts, the complexity of which was well adapted to the prevailing taste.

In what strange country, we may not unreasonably wonder, did the painter study the scenery of his Stormy Landscape, a landscape in the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, painted around 1640. The motives evidently belong to a land of dreams. The master has allowed imagination to run riot, treating his subject mainly as a pretext for those oppositions of light and shadow that he loved to render. In such visions the recluse would seem to have sought indemnity for his sedentary habits. As he painted, he felt himself transported to the fantastic regions of his dreams; the vast plains of Holland gave place to giant mountains, the vivid greens of her trees, and pastures to warm yellows and russets. In several smaller works such as the Landscape with the Good Samaritan, we note the same contrasts of light and shadow, the same magical chiaroscuro, the same conglomerate of slightly incongruous elements. The combination of incoherence in the composition with precision in the treatment of light, of careful imitation with flights of pure fantasy, proclaim the conflict in Rembrandt’s mind between opposing influences and the eagerness with which he strove to reconcile the visions that haunted him with the realities he loved.

Rembrandt had now completed his apprenticeship in landscape art. From this time forth, the contrast we have noted between the incoherence of his pictures and compositions in this genre, and the perfection of his drawings and sketches from nature, gradually disappeared. Rembrandt found distraction from his sorrows and disappointments, a renewal of his powers, and a further development of his genius. He still looked at nature with a poet’s eyes, but the hand with which he interpreted her had acquired the facility, the assurance, and the technical accomplishment that proclaim him a master.

Bathsheba with King David’s Letter, or Bathsheba Bathing, 1654

Oil on canvas, 142 x 142 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris

A Woman Bathing in a Stream (Hendrickje Stoffels?), 1654

Oil on oak, 61.8 x 47 cm. The National Gallery, London

Portrait of an Old Woman, 1654

Oil on canvas, 109 x 84 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Old Woman Reading, 1655

Oil on canvas, 80 x 66 cm. The Duke of Buccleuch Collection,

Drumlanrig Castle, Dumfries & Galloway

Rembrandt’s Technique and his Genius

Rembrandt, as we see, had, to a certain extent, shaken off the deep depression that had overwhelmed him after the death of Saskia. The loneliness of his position had the advantage, at least, that it enabled him to devote himself more ardently than ever to his work and the period we are about to deal with was one of the most productive of his busy life.

After an interval of some two years we find the artist returning to the Scriptural subjects he loved. Abraham Receives the Three Angels apparently belongs to this period. Christ and St Mary Magdalene at the Tomb, dated 1638, is imbued with a still deeper and more penetrating charm. The two solitary figures, the one illuminated by the light that shines from the other, the vague outlines, the melancholy of the place and hour, the majesty of death, the ineffable fusion of love and awe, together with countless other effects conceived with infinite delicacy and rendered with matchless eloquence, appeal to the soul and move it to its uttermost depths.

His Landscapes

One of Rembrandt’s finest etched portraits was inspired by another of the Italianates, the landscape-painter Jan Asselyn. A small night-piece dated 1647, is remarkable for its transparent shadows, and mysterious serenity of sentiment. The subject is Rest on the Flight into Egypt. The fugitives, surrounded by animals, are seated near a fire, the light of which is reflected in a quiet pool in the foreground. The picture is little more than a sketch, based on a composition of Elsheimer’s, to which the master has added a breadth and poetry all his own.

The latest of these painted landscapes, The Mill, is the masterpiece of the whole series. It could possibly be a composition, but it would be difficult to determine from the arrangement, and the general effect has all the appearance of a direct inspiration from nature. A silence, as of advancing night, broods upon the scene.

The spectator seems to hear the beat of water against some boat at anchor, and the furtive flight of an unseen bird in the thicket. Here the details are better chosen and less complicated; instead of distracting the attention, they enhance the melancholic poetry of the landscape.

Rembrandt’s studies were bearing fruit. He dared to be simple, to reject those complexities and artifices which had no part in nature, and to rely on reality for his effects.

Jacob Giving his Blessing to the Sons of Joseph, 1656

Oil on canvas, 173 x 209 cm. Staatliche Museen Kassel, Kassel

Hendrickje Stoffels (?) at the Door, c. 1656-1657

Oil on canvas, 88.6 x 67.9 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

Rembrandt’s Home-Life

A young servant named Hendrickje Stoffels, twenty-three years old, was destined to play an important part in the career of her master, with whom she remained until her death.

In several works of this period we recognise a feminine model whose apparent age agrees with Hendrickje’s. Hendrickje is easily recognisable in the picture, Bathsheba with King David’s Letter, or Bathsheba Bathing, painted in 1654. The seated figure is life-size, and the young woman appears to have just come out of the bath. We are prepared to admit that Bathsheba’s legs and the lower part of her body in general, are vulgar and ill-proportioned. The bust and throat, on the other hand, are exquisitely modelled. The light falls full upon them, bringing out the purity of their contours, and the luminous delicacy of the flesh-tints, which would bear comparison with the best work of Giorgione, Titian, and Correggio, the supreme painters of feminine nudity.

The finest of the whole series, however, is the study of Hendrickje known as Woman Bathing. It bears the same date as the Bathsheba (1654) and is undoubtedly a masterpiece among Rembrandt’s less important works. The truth of the impression, the breadth of the careful, masterly execution, and the variety of handling, all proclaim the matured power of the artist, and combine to glorify the hardy grace and youthful radiance of his creation.

When Rembrandt painted these various studies, he had secured the complaisant model for his life-long companion. Hendrickje had been his mistress for some time past. Careless of public opinion, he took little pains to conceal the situation, which soon created considerable scandal.

Young Woman with Earrings, 1657

Oil on panel, 39.5 x 32.5 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

A Strenuous Twilight

Rembrandt’s Financial Difficulties

With some small share of the method and foresight which Rubens displayed throughout his career, Rembrandt might have kept a roof over his head and honourably maintained his position in the first rank of Dutch artists. However, in addition to the general embarrassments in which his affairs became involved between 1652 and 1655, there were many purely personal causes for Rembrandt’s financial disaster. He had never learnt to save. He was generous, impulsive, and incapable of protecting his own interests. No sooner did he lay his hands on a sum of money, he lavished it on friends or relations, or on some caprice of the moment.

As Rembrandt’s embarrassments eventually became notoriously hopeless, and his ruin imminent, Saskia’s relatives, who had refrained from interference at first in deference to her wishes, felt it necessary to take action on behalf of Titus, of whose interests they were the legal guardians. A sum of 20,375 florins was therefore claimed for Titus, and Rembrandt, in satisfaction of this claim, appeared before the Chamber of Orphans on 17 May 1656, and signed over his interest in the house in the Breestraat to his son.

Having taken such precautions as he could to safeguard Titus’ interests, Rembrandt made some efforts, if not to satisfy his creditors, at least to temporarily appease them by payment of occasional sums out of the profits from the sale of his pictures. The numerous and important works produced by him in the year 1656, one of the most prolific of his career, attest to his industry.

An important picture, Jacob Giving his Blessing to the Sons of Joseph, claims mention as one of Rembrandt’s most accomplished works. The conception is one of the utmost nobility and pathos. Here, Rembrandt relies solely on the expression of human sentiment to give grandeur to the sacred theme, renouncing all the factitious dignity of picturesque accessories, fantastic architecture, and gorgeous costume, with which he rarely marred the solemnity of his Scriptural scenes.

Despite his courageous and determined industry, Rembrandt’s ruin was inevitable. His desperate attempts to raise money and to collect the sums due to him were all unavailing. Rembrandt was accordingly declared bankrupt. On 17 May 1656, the guardianship of Titus was transferred to a certain Jan Verbout.

Rembrandt’s ruin was complete. At the age of fifty-five he found himself homeless and penniless, stripped of all that had made life pleasant to him, compelled to leave his refuge in the inn without even paying the expenses of that dismal sojourn, during which all the treasures he had collected “with great discrimination” were divided among strangers before his eyes.

Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-Feather Fan, c. 1658-1660

Oil on canvas, 99.5 x 83 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Artaxerxes, Haman and Esther, 1660

Oil on canvas, 73 x 94 cm. The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Jacob’s Struggle with the Angel, c. 1659-1660

Oil on canvas, 140.1 x 120 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

Athena once known as Alexander the Great, c. 1660-1661

Oil on canvas, 118 x 91 cm. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon

Exile

His art was necessary to him more than ever, both as a diversion and a means of livelihood. But he felt strangely out of his element in the various temporary dwelling places in which he was forced to content himself, in comparison to the home which he had arranged to suit his own tastes and convenience. He had not only lost his engravings, his precious objects, his jewels, and all the accessories he had until this time considered essential to his art; but now, when advancing age was beginning to tell upon his sight, he was forced to accept such conditions of illumination as his improvised studios afforded.

The personality of the Saviour had always strongly attracted him; but now his own sorrows seem to have given him a peculiar insight into the His Life. He returns again and again to the Divine Figure, striving in each fresh attempt after a more complete suggestion of the ideal type he had conceived.

His art was, in fact, the sole direction in which he showed himself practical and clear-sighted.

The year 1661 is one of the most prolific in Rembrandt’s career. It was marked by the production of one superior and several important works. This fertility bears witness to the energy with which he had returned to his labours. He established himself this year in a house on the Rozengracht, where he remained until 1664.

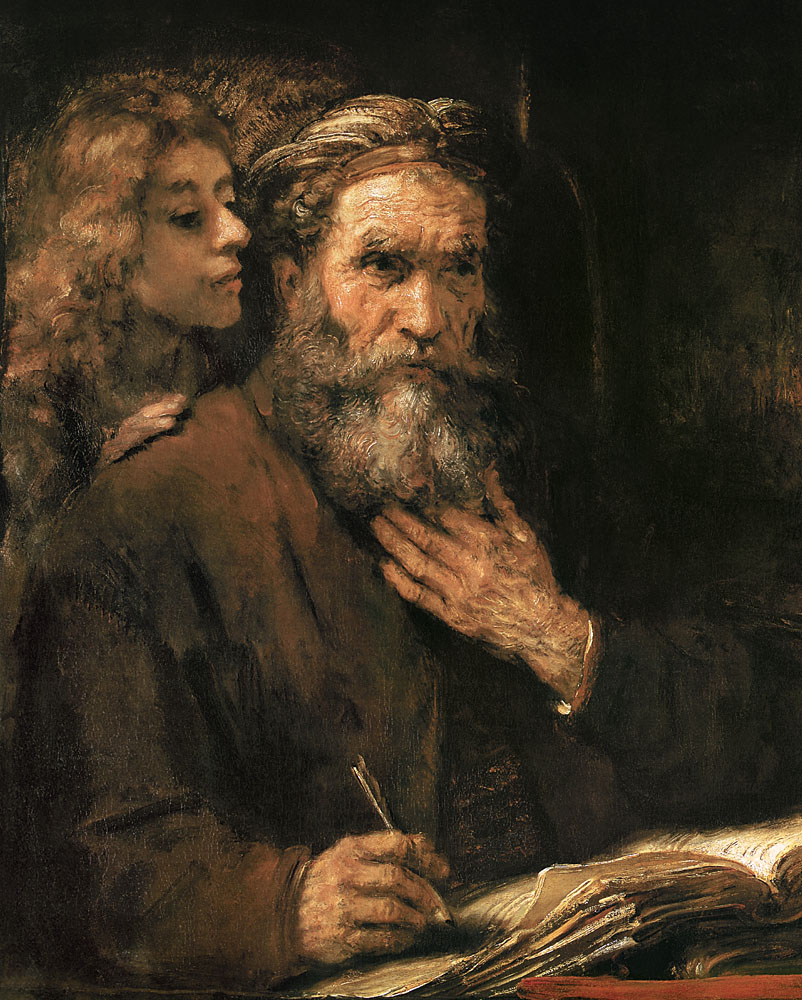

Saint Matthew and the Angel, dated 1661, is a subject of an elevated order. The apostle’s face, it is true, lacks nobility.

His features are coarse, his dress poor, and the harmony of the brown garment, the grey cap, and the rather strong flesh tints, is neither rich nor distinguished. The handling is harsh and abrupt, even coarse at times, but here and there we note those subtleties of expression peculiar to Rembrandt. The idea of concretely expressing the divine inspiration breathed into a human soul seems almost impossible, and wholly beyond the resources of painting. Yet Rembrandt has succeeded in rendering it with unrivalled clarity and eloquence.

The Syndics

Commissioned by the Guild of Drapers to paint a group portrait of their Syndics for the Corporation in 1662, Rembrandt delivered to them the great picture which has now been removed to the Rijksmuseum. As in earlier days in Florence, the wool industry held an important place in the national commerce of Holland and greatly contributed to the development of public prosperity. In Leyden, where the Guild was a large and important company, we know that the Drapers decorated their Hall with pictures representing the various processes of cloth-making painted by Isaac van Swanenburch.

On this occasion Rembrandt made no attempt to trade the traditional treatment of picturesque episode with novel pictorial means, as in the case of The Night Watch. He recognised, no doubt, that his patrons were far from grateful for such experiments, or it may be that they themselves made certain stipulations which left him no choice in the matter. In any case, Rembrandt accepted the convention of his predecessors in all its simplicity.

At first glance, we are fascinated by the extraordinary reality of the scene, by the commanding presence and intense vitality of the models. They are simply honest citizens discussing the details of their calling, but there is an air of dignity on the manly faces that compels respect. We note the solid structure of the heads and figures, the absolute truth of their values, the individual and expressive quality of each head, and their unity one with another. The vivid quality of the light is so illusory that it is difficult to conceive of it as artificial. So perfect is the balance of parts, that the general impression would be that of sobriety and reticence, were it not for the undercurrent of nerves, of flame, of impatience that we perceive beneath the outwardly calm maturity of the master.

Never before had he achieved such perfection; never again was he to repeat the triumph of that supreme moment when all his natural gifts joined forces with the vast experiences of a life devoted to his art in such a crowning manifestation of his genius. Brilliant and poetic, his masterpiece was at the same time absolutely correct and unexceptionable. In it the colourist and the draughtsman, the simple and the subtle, the realist and the idealist alike recognise one of the masterpieces of painting.

The Syndics: the College of Syndics (waardijns) of the Amsterdam Cloth Makers Guild, 1662

Oil on canvas, 279 x 191.5 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Portrait of Frederick Rihel on Horseback, probably 1663

Oil on canvas, 294.5 x 241 cm. The National Gallery, London

Haman Recognises his Fate, c. 1665

Oil on canvas, 127 x 116 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

His Last Years

Hendrickje’s health began to fail around this period. Although the exact date of her death is unknown, it probably took place before 1664. Sorrow after sorrow, each more cruel than the last, darkened the last years of Rembrandt’s life. It seems probable that he lost Hendrickje before 1664. The death of his faithful friend undoubtedly preceded his own, for after the year 1661 she disappeared from the master’s œuvre and no mention of her occurs in any of the documents relating to Rembrandt or his children.

His etchings, which had gradually declined in number, cease entirely from 1661 onwards. For some time prior, they were marked by an increasing hastiness and loss of delicacy. The life-studies and landscapes also come to an abrupt end, together with the etchings and landscapes in which he had taken so great a delight. When at last Rembrandt was able to resume his painting, his style had undergone a marked change. He was no longer able to attack complex subjects, which necessitated study and preparation. He now confined himself in general to one or two large figures, which he was content to sketch broadly on his canvas. All unnecessary details were dispensed with; he limited himself to the essentials of expression on which he concentrated all his powers. In time his harmonies became less intricate, his effects less subtle. The number of colours in his palette increasingly diminished. From this time on, he preferred the richest and most fervent: instead of purple he used bright red to which he mixed vivid yellows and savage tones. The execution itself became increasingly broad, simple, and decisive.

The Return of the Prodigal Son is unquestionably a work of Rembrandt’s latest period. Never did Rembrandt show greater power; never was his speech more persuasive. The free use of red tones, the vigorous execution, the ‘fine frenzy’ of the brushing, forbid the ascription of this masterpiece to a period of comparatively timid and tentative work. Here Rembrandt shows all the formidable strength of an unchained lion. In addition to the etching of 1636, Rembrandt produced many sketches of this subject which was one entirely suited to his genius. But never before had he risen to such a height of pathetic eloquence in its treatment. What force and originality of invention marks his conception of the father, who clasps his dearly loved child to his heart! Before this noble work we forget the roughness and harshness of the touch in admiration of the sentimental and expressive power. The absolute simplicity of the harmony, which is composed of browns, reds, and yellowish-whites, contributes to the intimate pathos of the scene, probably the last composition ever painted by the old master.

In happier days, he found it difficult to carry out his numerous commissions, yet towards the end of his life he could not sell his pictures, even at nominal prices. The embarrassments, inevitable under such conditions, were aggravated by crushing bereavements. Titus died in the year of his marriage. Broken down by poverty, and crushed by bereavements, the old master was not long parted from his son. His death, of which no mention is to be found in any extant contemporary document, is briefly noted in the death-register of the Wester Kerk as follows: “Tuesday, 8 October 1669; Rembrandt van Ryn, painter, on the Roozegraft, opposite the Doolhof. Leaves two children.” He, once the most famous painter of his age, and destined to be his country’s greatest glory, passed away without notice from men of letters or brother artists.

Portrait of Two Figures from the Old Testament known as The Jewish Bride, 1665

Oil on canvas, 121.5 x 166.5 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis, c. 1666

Oil on canvas, 196 x 309 cm. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Portrait of the Poet Jeremias de Decker, 1666

Oil on panel, 71 x 56 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Conclusion

With Rembrandt, vitality and truth were the rewards of sincere and unflagging labour. He never hesitated to correct, with the most ruthless strokes, a drawing that anyone else would have thought perfect as it stood. Until he could express his idea, until a figure had the exact turn or appearance he desired, his hand was pitiless. In all such matters he was as exacting as Leonardo, Poussin, or any others among those acknowledged masters of form who knew no weariness in their search for the line, attitude, or gesture which said what they wished to say with the greatest precision. He never ceased to learn, to renew his own powers, and to give to each work all the perfection of which it was capable.

Rembrandt, in fact, belongs to the class of artists which can have no posterity. His place is with the Michelangelos, the Shakespeares, and the Beethovens. An artistic Prometheus, he stole the celestial fire and with it put life into what was inert, and expressed the immaterial and evasive sides of nature in his breathing forms. Bold spirits are attracted by the infinite. The ideal they pursue flies continually before them. They give themselves over body and soul to the sublime pursuit, and as the sentiment by which they are spurred exists in embryo in every human soul, they call up in every one of us some echo of the thoughts which agitate themselves. Only in their world of art do they discover beauties before undreamt, and in the very act of appropriating the inventions of their forerunners, they invent in their turn. They become more and more foreign to their own time; but enlightened by that flame of genius which, before it expires, blazes up to throw a last dazzling ray upon their talent, they go steadily on, leaving to those who come after them the task of recognising beauties which may break accepted rules, but which nevertheless will be a law to the future.

Return of the Prodigal Son, c. 1668

Oil on canvas, 262 x 205 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg