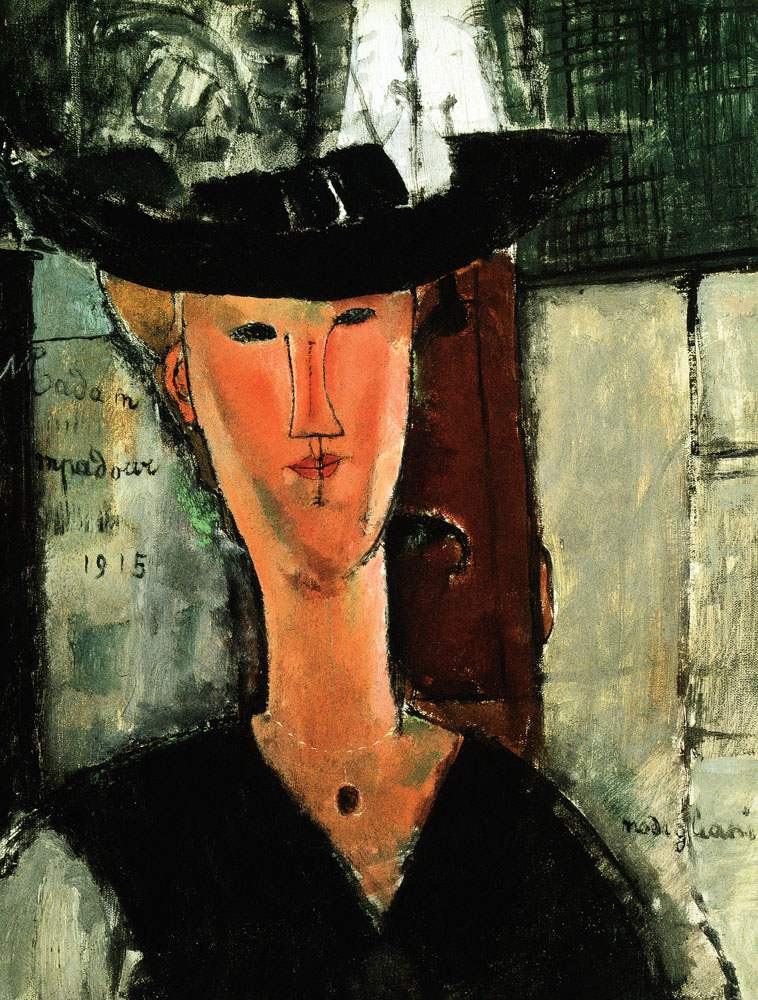

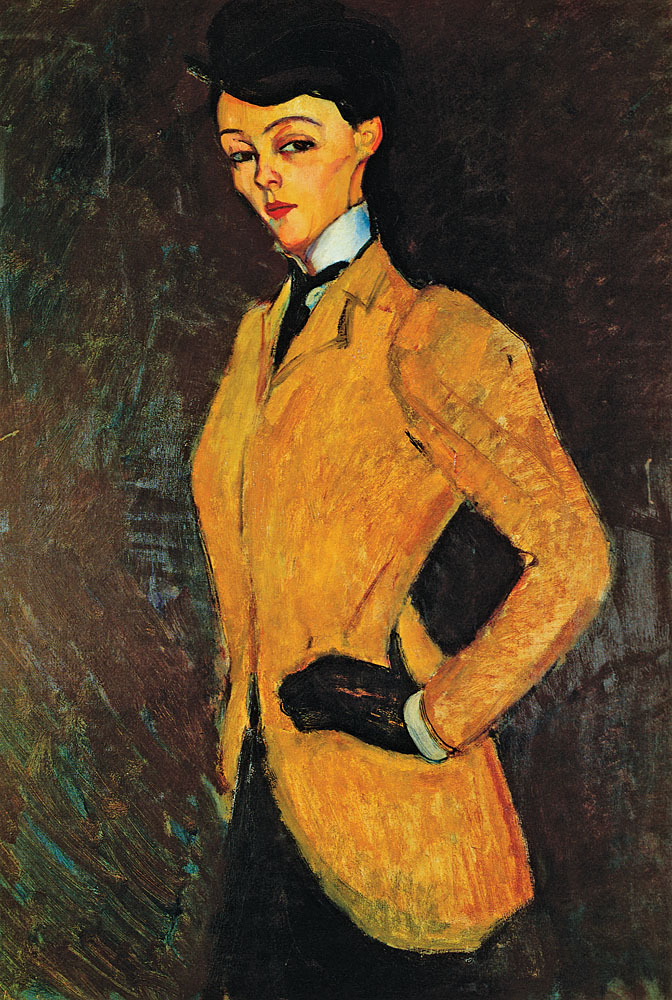

Madam Pompadour, 1915. Oil on canvas, 61.1 x 50.2 cm. Joseph Winterbotham Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

His Life

Amedeo Modigliani was born in Italy in 1884 and died in Paris at the age of thirty-five. He was Jewish with a French mother and Italian father and so grew up with three cultures.

A passionate and charming man who had numerous lovers, his unique vision was nurtured by his appreciation of his Italian and classical artistic heritage, his understanding of French style and sensibility, in particular the rich artistic atmosphere of Paris at the turn of the 20th century, and his intellectual awareness inspired by Jewish tradition.

Unlike other avant-garde artists, Modigliani painted mainly portraits – typically unrealistically elongated with a melancholic air – and nudes, which exhibit a graceful beauty and strange eroticism.

In 1906, Modigliani moved to Paris, the centre of artistic innovation and the international art market. He frequented the cafés and galleries of Montmartre and Montparnasse, where many different groups of artists congregated.

He soon became friends with the Post-Impressionist painter (and alcoholic) Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955) and the German painter Ludwig Meidner (1844-1966), who described Modigliani as the “last, true bohemian” (Doris Krystof, Modigliani).

Modigliani’s mother sent him what money she could afford, but he was desperately poor and had to change lodgings frequently, sometimes abandoning his work when he had to run away without paying the rent.

Fernande Olivier, the first girlfriend that Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) had in Paris, describes one of Modigliani’s rooms in her book Picasso and His Friends (1933):

A stand on four feet in one corner of the room. A small and rusty stove on top of which was a yellow terracotta bowl that was used for washing in; close by lay a towel and a piece of soap on a white wooden table. In another corner, a small and dingy box-chest painted black was used as an uncomfortable sofa.

A straw-seated chair, easels, canvasses of all sizes, tubes of colour spilt on the floor, brushes, containers for turpentine, a bowl for nitric acid (used for etchings), and no curtains.

Modigliani was a well-known figure at the Bateau-Lavoir, the celebrated building where many artists, including Picasso, had their studios. It was probably given its name by the bohemian writer and friend of both Modigliani and Picasso, Max Jacob (1876-1944).

While at the Bateau-Lavoir, Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the radical depiction of a group of prostitutes that heralded the start of Cubism.

Other Bateau-Lavoir painters, such as Georges Braque (1882-1963), Jean Metzinger (1883-1956), Marie Laurencin (1885-1956), Louis Marcoussis (1878-1941), and the sculptors Juan Gris (1887-1927), Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973) and Henri Laurens (1885-1954) were also at the forefront of Cubism.

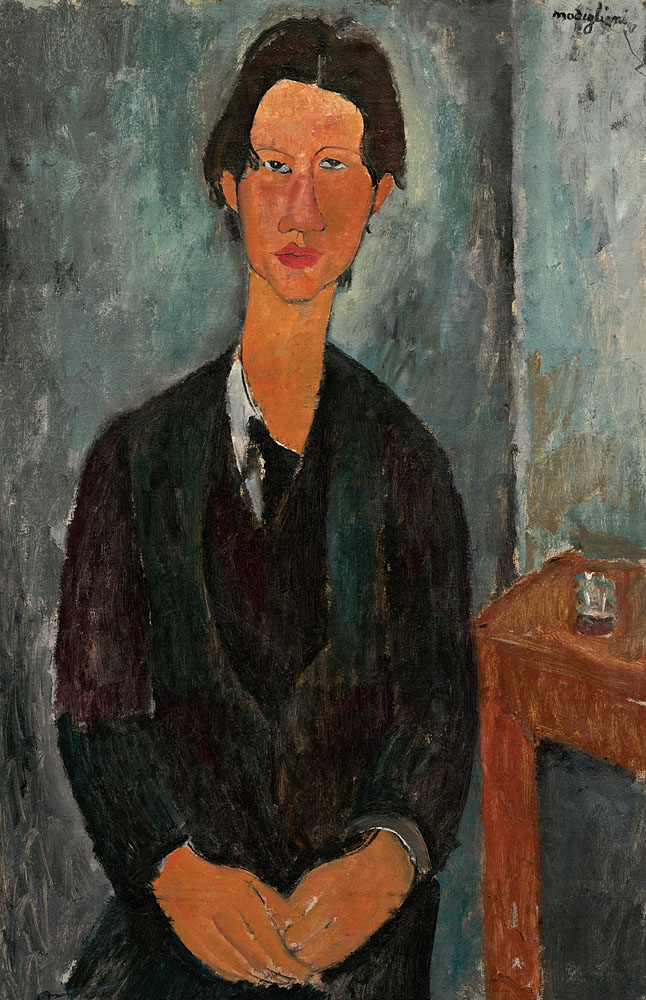

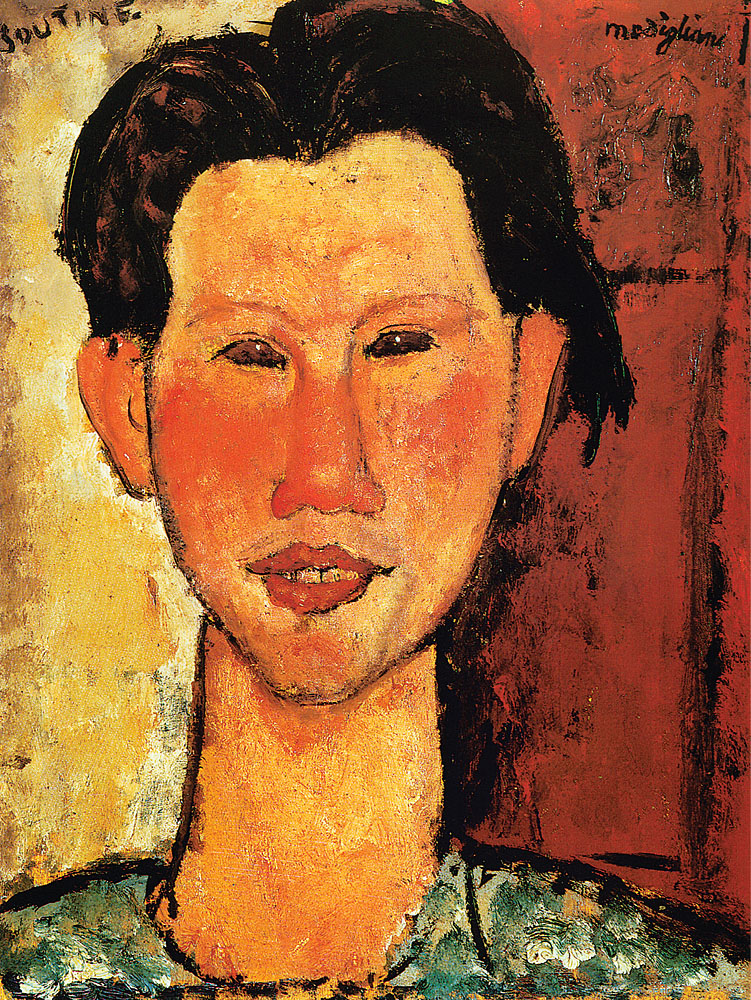

The vivid colours and free style of Fauvism had just become popular and Modigliani knew the Bateau-Lavoir Fauves, including André Derain (1880-1954) and Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958), as well as the Expressionist sculptor Manolo (Manuel Martinez Hugué, 1872-1945), and Chaim Soutine (1893-1943), Moïse Kisling (1891-1953), and Marc Chagall (1887-1985). Modigliani painted portraits of many of these artists.

Max Jacob and other writers were drawn to this community which already included the poet and art critic (and lover of Marie Laurencin) Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), the Surrealist Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), the writer, philosopher, and photographer Jean Cocteau (1889-1963), with whom Modigliani had a mixed relationship, and André Salmon (1881-1969), who went on to write a dramatised novel based on Modigliani’s unconventional life.

The American writer and art collector Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) and her brother Leo were also regular visitors.

Modigliani was known as ‘Modi’ to his friends, no doubt a pun on peintre maudit (accursed painter).

He himself believed that the artist had different needs and desires, and should be judged differently from other, ordinary people – a theory he came upon by reading such authors as Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), and Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938).

Modigliani had countless lovers, drank copiously, and took drugs. From time to time, however, he also returned to Italy to visit his family and to rest and recuperate.

In childhood, Modigliani had suffered from pleurisy and typhoid, leaving him with damaged lungs. His precarious state of health was exacerbated by his lack of money and unsettled, self-indulgent lifestyle.

He died of tuberculosis; his young fiancée, Jeanne Hébuterne, pregnant with their second child, was unable to bear life without him and killed herself the following morning.

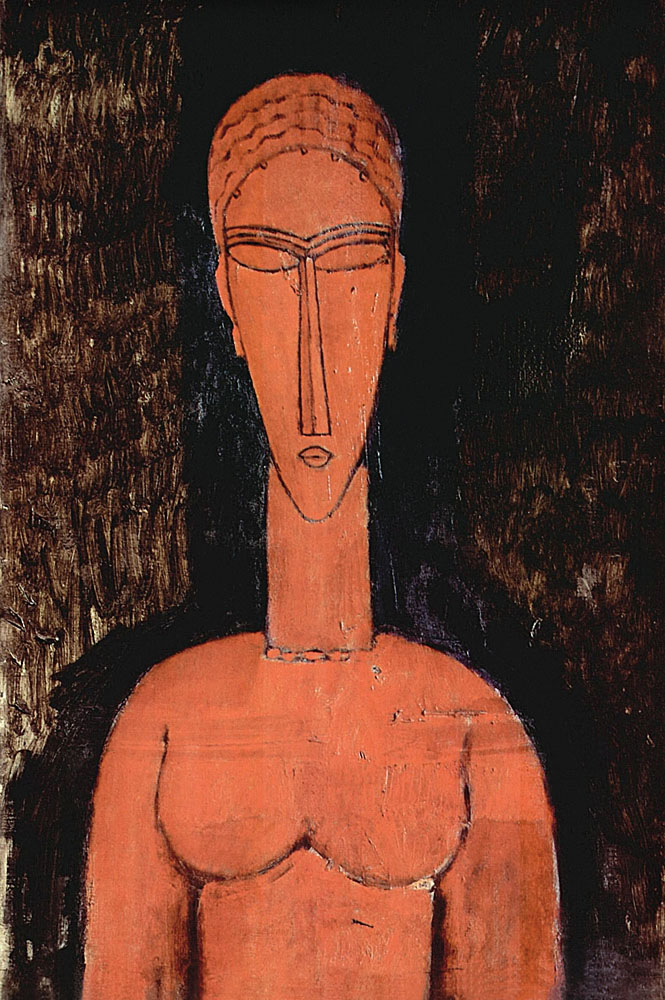

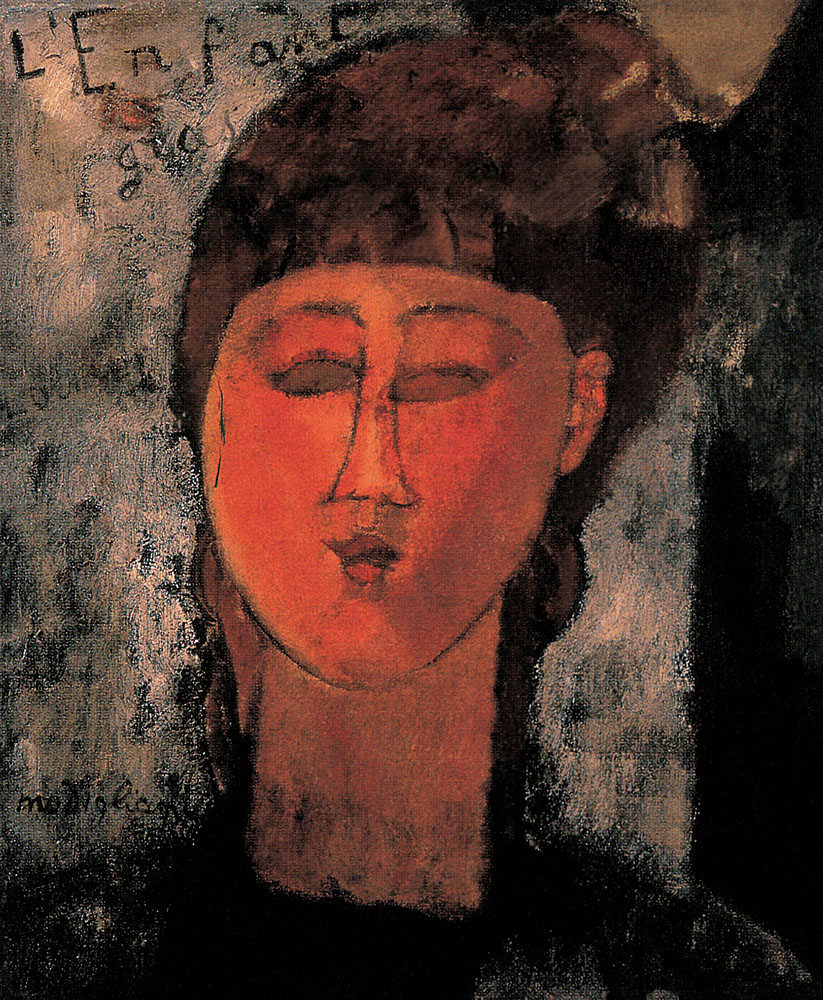

Woman with Red Hair, 1917. Oil on canvas, 92.1 x 60.7 cm. Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

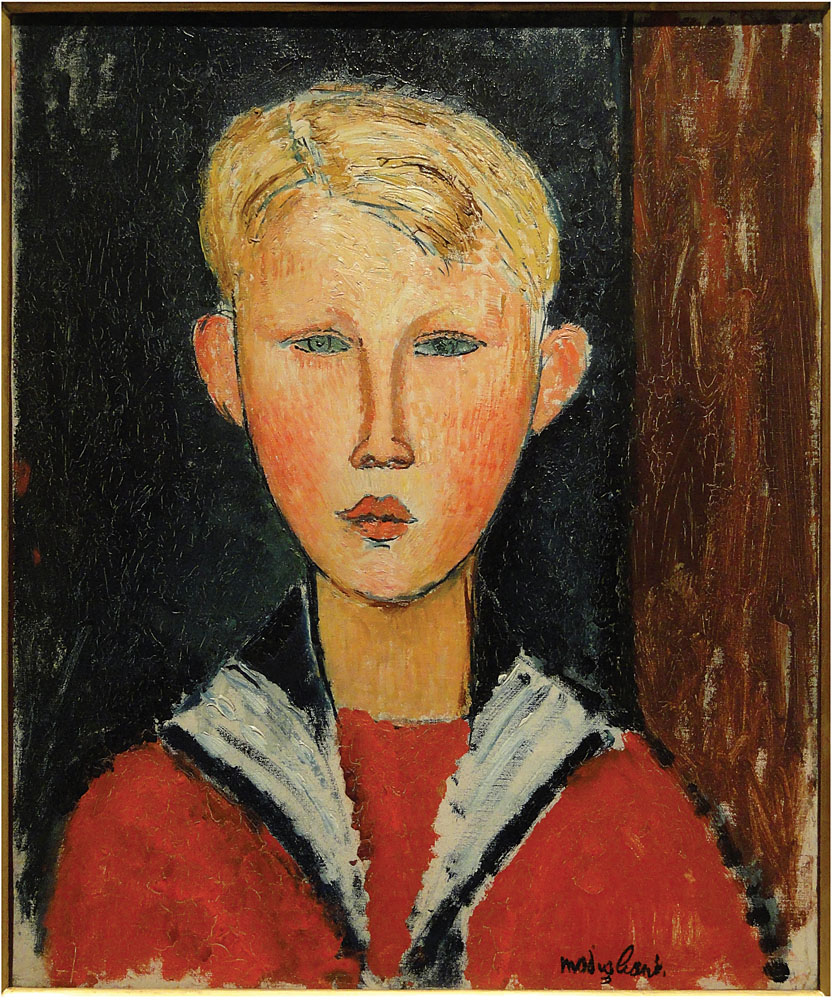

Chaim Soutine, 1917. Oil on canvas, 91.7 x 59.7 cm. Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

From Tradition to Modernism

A Reinterpretation of Classical Works

Modigliani’s first teacher, Guglielmo Micheli (d. 1926), was a follower of the Macchiaioli school of Italian Impressionists. Modigliani learned both to observe nature and to understand observation as pure sensation.

He took traditional life-drawing classes and immersed himself in Italian art history. From an early age he was interested in nude studies and in the classical notion of ideal beauty.

In 1900-1901 he visited Naples, Capri, Amalfi, and Rome, returning by way of Florence and Venice, and studied first-hand many Renaissance masterpieces.

He was impressed by trecento (13th-century) artists, including Simone Martini (c. 1284-1344) whose elongated and serpentine figures, rendered with a delicacy of composition and colour and suffused with tender sadness, were a precursor to the sinuous line and luminosity evident in the work of Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445-1510).

Both artists clearly influenced Modigliani, who used the pose of Botticelli’s Venus in Birth of Venus (1482-1485) in his Venus (Standing Nude) (1917) and Young Woman in a Camisole (1918), and a reversal of this pose in Seated Nude with Necklace (1917).

The sculptures of Tino di Camaino (c. 1285-1337) with their mixture of weightiness and spirituality, characteristic oblique positioning of the head and blank almond eyes also fired Modigliani’s imagination.

His distorted composition and overly lengthened figures have been compared to those of the Renaissance Mannerists, especially Parmigianino (1503-1540) and El Greco (1541-1614). Modigliani’s non-naturalistic use of colour and space are similar to the work of Jacopo da Pontormo (1494-1557).

For his series of nudes Modigliani took compositions from many well-known nudes of High Art, including those by Giorgione (c. 1477-1510), Titian (c. 1488-1576), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), and Velázquez (1599-1660), but avoided their romanticisation and elaborate decorativeness.

Modigliani was also familiar with the work of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) and Édouard Manet (1832-1883), who had caused controversy by painting real, individual women as nudes, breaking the artistic conventions of setting nudes in mythological, allegorical, or historical scenes.

Discovery of New Art Forms

Modigliani’s exposure to ancient art, art from other cultures, and Cubism influenced his own work to such an extent that he began to break more and more from the classical tradition. African sculptures and early ancient Greek Cycladic figures had become very fashionable in the Parisian art world at the turn of the century.

Picasso imported numerous African masks and sculptures, and the combination of their simplified abstract approach and use of multiple viewpoints were the direct inspiration for Cubism.

Modigliani was impressed by the way the African sculptors unified solid masses to produce abstract but pleasing forms that were decorative but had no extraneous detailing. His interest in such work is illustrated by his Sheet of Studies with African Sculpture and Caryatid (c. 1912-1913).

He sculpted a series of African-inspired stone heads (c. 1911-1914), which he called “columns of tenderness”, and envisaged them as part of a “temple of beauty”.

His friend, the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957), introduced Modigliani to early ancient Greek Cycladic figures. These, along with Brancusi’s own work, inspired Modigliani’s caryatids.

Modigliani was interested in the depiction of solidity, and caryatids as weight-bearing structures unified the concepts of power as well as grace to form the ideal motif.

The details in Modigliani’s caryatids, however, show a modern awareness of sexuality and a desire to render a sense of the fleshy femininity of the figures. Caryatid (c. 1914) has her arms behind her head in a pose more often associated with sleep and foreshadows the pose of Reclining Nude with Open Arms (Red Nude) (1917).

The caryatid narrows at the waist, but her belly and full thighs are massive and reflect her full, round arms and head. Her pose echoes Renaissance use of contrapposto and shows Modigliani’s awareness of the pliability of her flesh and the sensuousness of her fully curved figure.

The Pink Caryatids (1913-1914) have even fuller curves and display a lush use of luminous colour. They are essentially patterns of circles and are highly geometric.

It was the Cubist approach, developing the ideas of Cézanne, that led Modigliani to stylise the caryatids into such geometric shapes. Their balanced circles and curves, despite having a voluptuousness, are carefully patterned rather than naturalistic.

Their curves are precursors of the swinging lines and geometric approach that Modigliani later used in nudes such as Reclining Nude. Modigliani’s drawings of caryatids allowed him to explore the decorative potential of poses that may not have been possible to create in sculptures.

The raised arms of Caryatid (c. 1911-1912) give her a stylised, ballet posture. Apart from her fully rounded breasts and the curving outline to her hip and thigh, she is more angular and lean than most of Modigliani’s caryatids.

Caryatid (1910-1911; charcoal sketch) has a similar angled head and uplifted leg. In Caryatid (c. 1912-1913) Modigliani has emphasised the raised thigh and pointed breast, showing his intention to present the figure as a sexual female.

The Caryatid dated to around 1912 faces the viewer and can be seen as a predecessor of Modigliani’s standing nudes. The geometrising of the figure is apparent, as is the reduction to simple forms.

Caryatid (1913) is a more highly worked version with fine detailing on the nipples and navel. The slight curve of the right leg where it bends at the knee is an enlivening and humanising detail.

The curious patterned lines across her belly suggest necklaces and emphasise the cone shape of her abdomen and the sexual triangle at the top of her thighs.

Standing Nude (c. 1911-1912) no longer functions as a caryatid and is a true nude study, showing an architectural approach to the body. Her folded arms frame her heavily outlined breasts, while her face remains abstract and Africanised.

The sketch of the Seated Nude (c. 1910-1911) is a fully realised nude drawing and shows the completion of Modigliani’s transition from the caryatids to the true nudes. He allows the lines of the figure’s body to swing in a more expressive approach to her eroticism.

Only one caryatid sculpture in limestone, Caryatid (c. 1914), has survived. It is rough-hewn unlike the stone heads, so Modigliani may have abandoned it without finishing it, or possibly left it unrefined to give it a powerful appearance.

Although her pose is similar to the caryatid drawings, the forms are massive and bulky, and less geometrical and more naturalistic in detailing.

The treatment of the breasts and stomach show Modigliani’s understanding of the underlying musculature and his interest in resolving solid forms at awkward points, such as the area between the breast, neck and arm.

The influences of Cézanne and Expressionism are clear in the harshness of Sorrowful Nude (Nudo Dolente, 1908), one of Modigliani’s early nudes, which lacks the luxuriant sexuality of his later nudes. It is a disturbing rather than attractive image; the figure’s upturned face with full, slightly parted lips and half-closed eyes hint at a state of frenzy, perhaps agony, perhaps pleasure. The painting illustrates Modigliani’s willingness to experiment stylistically and express his intensity and passion.

In 1909 Modigliani, like many other artists at that time, moved to Montparnasse, where his friend Brancusi lived. The Café du Dôme on the south side of Montparnasse Boulevard was especially popular with German artists, while the Café de La Rotonde on the north side of the boulevard was a favourite haunt of the Japanese painter Tsuguharu Fujita (1886-1968) and his friends.

The influence of the innovative painters of the late 19th century, such as Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) and “Le Douanier” Henri Rousseau (1844-1910), could still be felt, while younger artists, such as André Derain and the Fauves, Pablo Picasso, Ossip Zadkine (1890-1967) and the Cubists, were creating their own styles.

The exchange of ideas must have been phenomenal, and art dealers and collectors, such as Paul Guillaume (1891-1934), whom Modigliani met in 1914, and Leopold Zborowski (1889-1932), who became friends with Modigliani in 1916, also frequented the area. Amidst this hotbed of ideas Modigliani came to understand many styles before finding his own path. So fast was the pace of innovation that by the time Modigliani was developing his African-influenced Cubist style, the original Cubists were pursuing new ideas. For example, in his sketch Caryatid Study a clear similarity to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon can be seen in the angular pose, weighty raised arms, and use of differing viewpoints.

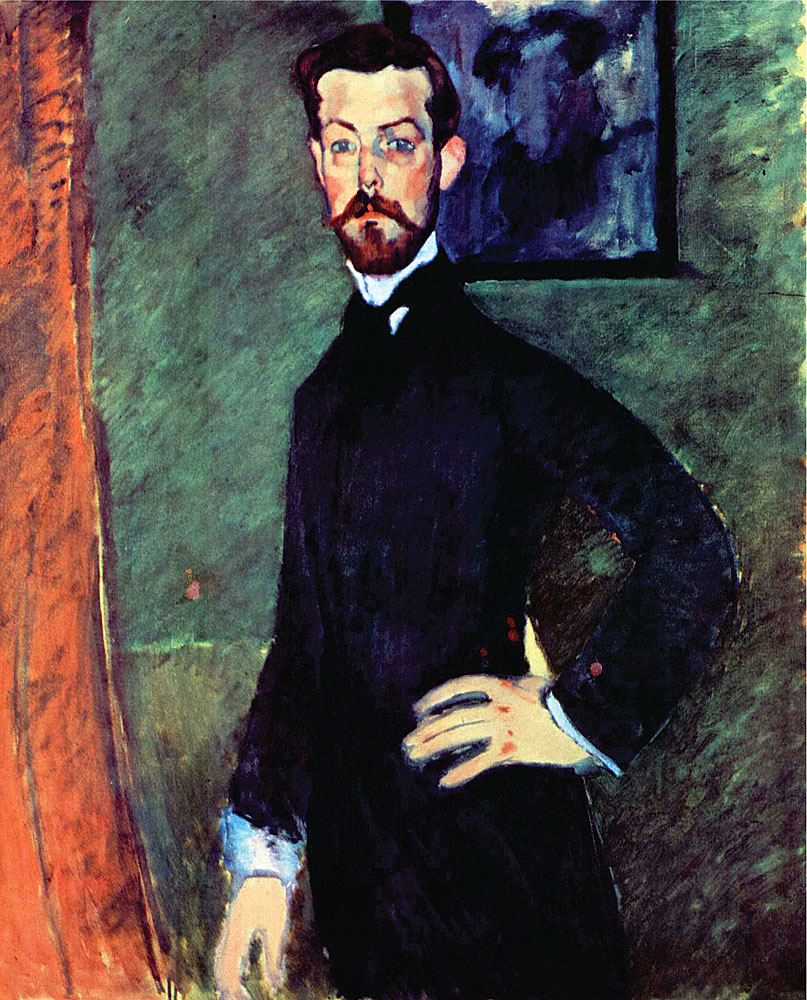

Portrait of Paul Alexandre with Green Background, 1909. Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm. Private collection.

The Nudes and Moral Values

Modigliani was fascinated by the way that outline can be used to represent volume. He wanted to translate the solidity of sculpture onto flat canvas while capturing the essence of classical elegance. This unwillingness to abandon the past led to criticism of his work by his avant-garde contemporaries, the Futurists, whose manifesto he had refused to sign.

The Futurists believed that art should concern itself only with modern styles and themes, such as machinery and motor cars. They thought Modigliani’s paintings were too old-fashioned and they rejected the female nude because it was one of the standard subjects of traditional art. However, Modigliani’s approach to the nude was so individual and innovative that traditionalists were shocked by his work.

An Unconscious Liberation

Goya’s The Naked Maja (1798-1805) had caused consternation because it depicted a real and well-known lady of the court. Modigliani adapted the composition for many of his nudes, such as Nude with Coral Necklace (1917), Nude (1919), and Reclining Nude with Open Arms (Red Nude) (1917). However, Goya’s painting has an aloof air and is deliberately posed, and so has a formality that is familiar from High Art. On the other hand, Modigliani avoids formal compositions, settings, and techniques, so his nudes have a wildness and freedom that make them modern and striking.

Manet’s Olympia (1863) was criticised when first shown, mainly because the model was an ordinary Parisian prostitute and therefore not considered a worthy subject for art, but also because she is gazing directly and openly at the viewer. This forces viewers to admit that they are admiring a prostitute, rather than allowing them to pretend that seeing a nude was an almost unintentional consequence of following a literary narrative or deciphering an allegorical scene. Similarly there is no ornate landscape or richly-drawn fabric to put Modigliani’s Nude (1919) in a mythological or pastoral setting, even though she lies obliquely across the canvas with her right arm behind her head in a pose like that of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (c. 1508-1510).

Nude on a Blue Cushion (1917) also borrows the pose of Sleeping Venus, but she is not demurely sleeping, unaware that she is being watched. Her full, red, sensual lips highlight both her attractiveness and her desire. This makes her more vivid and tangible than Sleeping Venus despite being less realistic in style. Manet’s Olympia challenged the observer to enter into a visual transaction with the prostitute gazing back out of the picture. But the blue eyes of Modigliani’s figure add to this challenge a disconcerting surrealism. Her blank eyes stare, but stare blindly, so she is both confronting the viewer and remaining oblivious.

Eyes were a potent image in Symbolism as the ‘mirrors of the soul’, representing introspection as well as observation. Modigliani was a keen reader of Symbolist poetry, often reciting verses from memory, and would have seen Symbolist works by such artists as Odilon Redon (1840-1916), Edvard Munch (1863-1944), and Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) at the Venice Biennial Exhibition in 1903.

The gaze of Modigliani’s empty-eyed nudes is perhaps their most unnerving feature, especially in contrast with both the passive and comforting averted or closed eyes of most classical nudes and Olympia’s bold but recognisable stare.

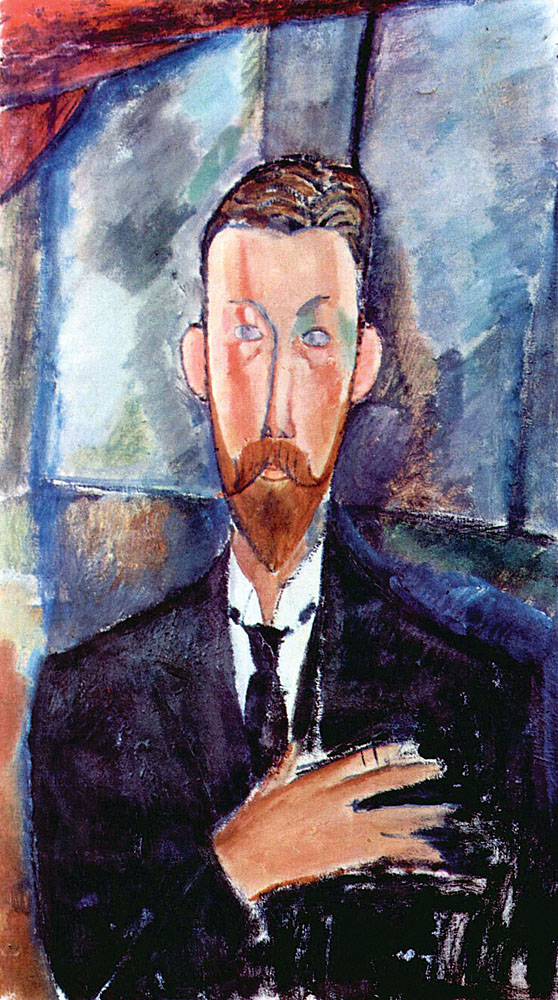

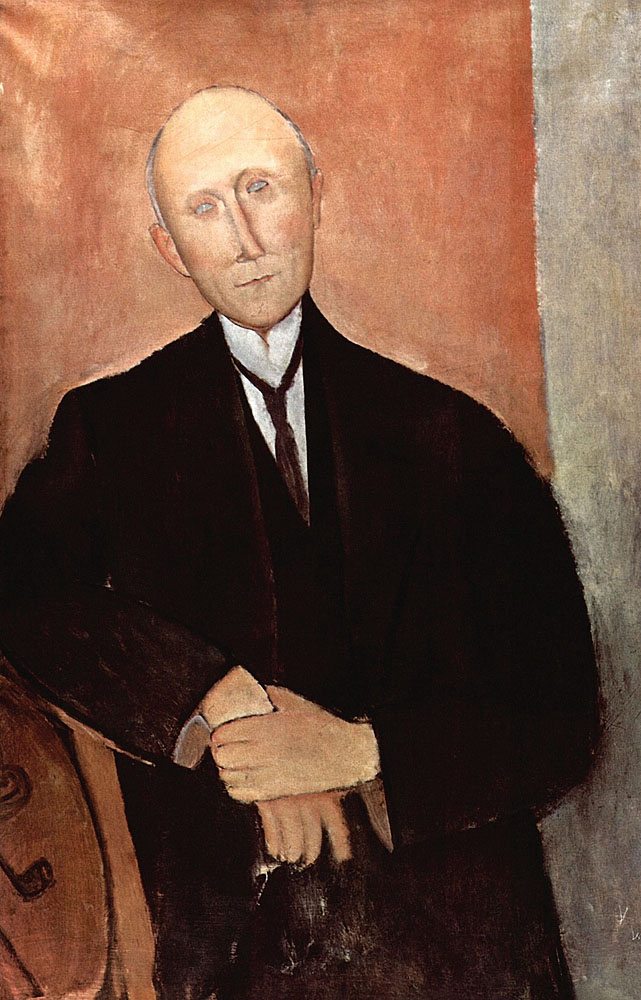

Portrait of Paul Guillaume, Novo Pilota, 1915. Oil on cardboard, 105 x 75 cm. Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris.

The cold, disinterested expression of Nude Looking over Her Right Shoulder (1917) makes her seem annoyed that she is being watched. It is like the look of someone who has turned around to discover her photograph is being taken. She does share, however, the pose of Venus in The Toilet of Venus (c. 1647-1651) by Velázquez, but unlike Venus, who stares only at her own reflection, she is looking out of the picture, at the viewer.

Meanwhile Modigliani draws the gaze of the viewer to her full hips and buttocks at the focus of the composition. The story goes that Modigliani met the ageing Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), who described painting one of his pictures as repeatedly caressing the buttocks of the nude; Modigliani retorted rudely that he did not like buttocks. Indeed, most of his nudes are viewed from the front, and perhaps this explains some of the untypical tension of his painting.

Modigliani does not identify his models, so they may represent goddesses or prostitutes. The images therefore have to be considered purely in their own terms for they make no obvious social or political comment. This decontextualising, however, was highly political in a society that was still largely governed by 19th-century prudery and strict social hierarchies.

Representations of nudity were considered morally acceptable only if they were presented according to the traditional artistic formulae which distanced the images from everyday life. This enabled people to enjoy looking at nudes while maintaining repressive attitudes towards sexuality in general. Modigliani was not a social elitist and considered the beauty and sexuality of ordinary women to be neither shameful nor an unworthy subject for great art. He does not add details or backgrounds to his nudes that would show them to belong to a particular social class or role.

This discourages the observer from making moral judgements about the status or lifestyle of the figures and so promotes a purely aesthetic approach. Such disregard for the old systems was threatening to those who feared female sexuality and bohemian liberality.

Manet’s Olympia caused outrage because it celebrated a confident and unashamed prostitute. Most of Modigliani’s nudes are not coy and demure like Giorgione’s Venus or Titian’s nudes. Their attitude, along with the reduction of narrative and subject matter to nothing but the erotic body presented for its own sake, was considered scandalous.

It is ironic that these works by Modigliani, who deeply respected classical tradition and wanted to belong to it, were seen not as High Art but as outrageous depictions of naked women. The police, who closed down his first and only solo show, held at the Berthe Weill Gallery in 1917, expressed horror that Modigliani had painted the models’ pubic hair, a tiny detail that nonetheless flouted artistic conventions. Earlier artists, such as Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), had taken delight in painting with such realism, but had not been allowed to show such work in public.

Modigliani did not see his nudes as the indulgence of private fantasies, and so did not see why they should not be put on public display. Clearly a great many people agreed. It was the crowd that came to see his show that drew the attention of the police. Modigliani’s exhibition was closed down not simply because his paintings were deemed immoral but because they were popular.

One of the first in his series of nudes, Female Nude (c. 1916), may be a portrait of Beatrice Hastings, an eccentric English writer with whom Modigliani had an affair from 1914 to 1916. She was very supportive of him, especially when he returned to painting after he had finally given up sculpture because of the expense of the materials and the irritation that the stone dust caused his lungs.

Female Nude was certainly created with her encouragement. The outline is less sure than in later works: it is uneven and broken, and the head with its sharp chin sits rather awkwardly. The down-turned face functions to direct the viewer’s gaze to the centre of the canvas and the centre of her body.

The fall of her hair emphasises the shape of her breast, and the delicate gradations of colour mark out the full roundness of the curves of her belly. She forms an elegant oblique across the canvas, the light to the left and the dark to the right, with just enough attention to the background to frame the figure without defining the space. Modigliani’s attention to detail is only apparent in a few places, notably the pubic hair. The glowing use of colour gives the body vibrancy while the model herself sleeps.

The sketch Seated Nude (1918) also has a somewhat uncomfortable pose, with a dramatic twist to the stomach, an exaggerated contrapposto, and an unresolved lower thigh. However, the feeling of motion and a youthful softness created by the delicacy of the curves give the figure a warmth and charm. The detailing in the upturned face is just enough to give her a sensuous, blissful air.

Another Seated Nude (c. 1918) is distorted and mannered, showing a Cubist influence. The shoulders, legs, and buttocks are not fully drawn, and the asymmetrical eyes make the image strange and less instantly appealing than the former, Seated Nude (1918). However, there is a languid charm to the tilted head and the slackness of the body exudes relaxation. This conveys a dream-like eroticism that is all the more potent for its subtle portrayal.

A similarly odd atmosphere pervades Nude on a Blue Cushion (1917). Modigliani again does not complete the modelling of her legs but takes careful observation of the form of her breasts. Her quizzical and enchanting expression makes her seem awake and lively but her eyes are nonetheless unreal, so her seductive gaze is timeless and undirected. The heavy plasticity of her body owes much to Modigliani’s experience of depicting the caryatids: her form is majestic and sculptural, while the composition is photographic – her legs and the top of her head are cut off and ‘out of shot’.

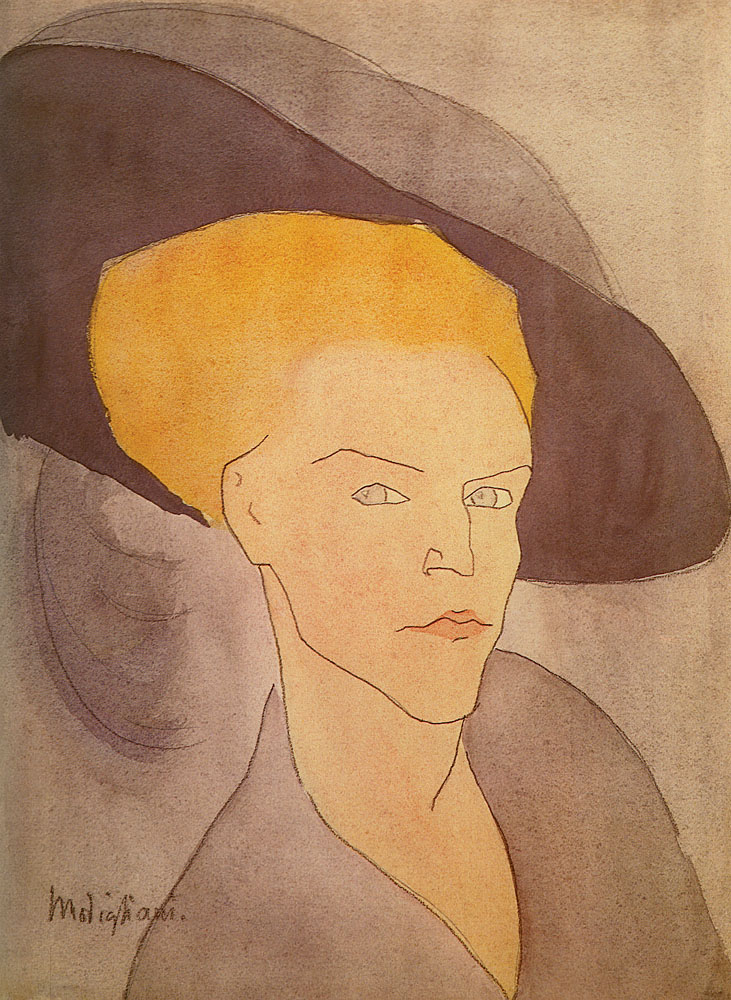

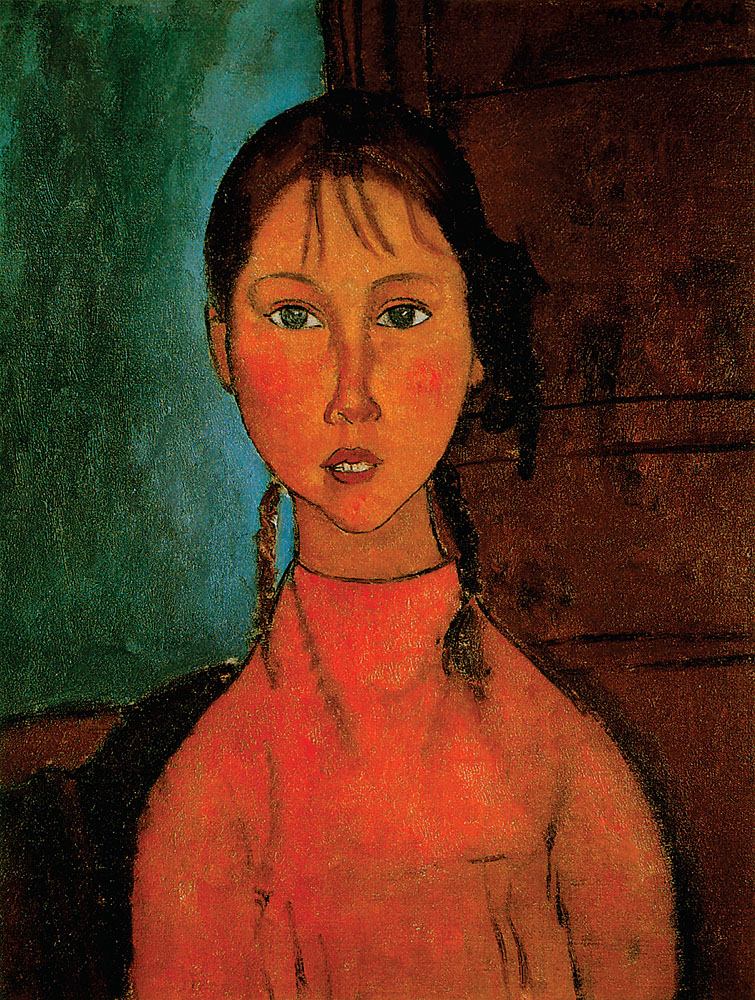

Red Head, 1915. Oil on cardboard, 54 x 42.5 cm. Musée national d'Art moderne, Centre Georges-Pompidou, Paris.

The Art of the ‘Close-Up’

Modigliani often takes a very close viewpoint for his pictures – far closer than most earlier painters of nudes. This was no doubt due to the influence of the new medium of photography, especially the erotic photography that was coming into vogue. His use of this technique heightens the sense of physical presence of the figure and the artist’s proximity to the model.

Modigliani cuts short the legs of almost all his nudes and many also have part of the head or arms cropped to create a snapshot effect. This device is particularly striking in Reclining Nude with Open Arms (Red Nude) (1917).

By placing the model’s body in the centre of the picture as if it were bursting out of the frame, Modigliani accentuates only the sexual aspects of the figure. Absolutely nothing else is of interest. The snapshot style makes the figure accessible as well as utterly dispenses with traditional rules of completeness in composition. Despite the careful brushwork and skilled use of delicate tonal variation, the overall effect is of effortless spontaneity – the complete opposite of the traditional notion that quality is the same as scholarly studiousness.

The spontaneous flamboyance of Modigliani’s nudes made them appear all the more brazen and shameless to conservative eyes. The open enjoyment of the erotic that appears in his paintings was reflected in the sexual liberty of Modigliani’s own life.

Even as a teenager he had a reputation as a seducer: when he was an art student in Venice he apparently spent more time in cafés and brothels than attending courses and in Paris he had numerous lovers, although there is little evidence and much speculation about his liaisons. He was said to have slept with all of his models, some of whom were well-known in the artistic community: Kiki, the Queen of Montparnasse, Lily, Massaouda la négresse, Elvira, the wild young runaway daughter of a Spanish prostitute, and Simone Thirioux, who bore him a son.

However, there are no nude paintings definitely identifiable as Elvira or Simone, and only one sketch that is definitely Beatrice Hastings. It is likely that he paid some professional models without having sexual relationships with them, and that he painted some of his lovers who were not professional models.

By the end of his series of nudes, Modigliani had reached the zenith of his style. He suggested volume with elegant arching arabesques and had achieved the utmost in simplification and abstraction.

For example, Reclining Nude (c. 1919) shows Modigliani’s full command of line. The outline is even and precise. The distortion of the hips is non-naturalistic but not jarring and hints at, rather than proclaims, the figure’s sexuality. He uses a restrained palette, which gives the picture an air of tranquillity, and the artist’s hand is masked by an ease of execution and delicacy of brushwork that adds to the transcendent atmosphere. She is bathed in a gentle light, and subtle tonal changes mark out her form so lightly that she appears to float against the dark background.

Standing Nude (Elvira) (1918) is called Elvira even though Modigliani’s affair with her had ended several years earlier. The model holds a folded cloth just low enough to suggest that she is completely naked, but this echoes, and perhaps even parodies, the suggested modesty of the great classical nudes.

She has a rigidly geometric pose and her full breasts are almost perfect hemispheres. Her blank gaze has a sense of boldness and is totally still. This gives her a monumental sculptural quality. Her eroticism appears suspended and her personality is frozen. She is like a stone statue: not a real woman but merely a physical form, reified and depersonalised. Again, the absence of background detail adds to the timelessness of the image.

Emotional Involvement

A Depersonalising Process

Despite depicting his models as particular individuals, Modigliani makes surprisingly little effort to engage with them emotionally or to portray them psychologically. He maintains his objectivity and distance as an artist, especially in his later nudes, and does not overtly attempt to solicit any specific emotional reaction from the viewer. This allows the viewer a freedom of response, but also distances the artist from any direct involvement in that response.

Censors even as late as the 1940s and 1950s saw the paintings as obscene and pornographic, but Modigliani was not deliberately setting out to provoke such a response. Modigliani’s unrepressed sexuality enabled him to express his desires with a carefree joy that bordered on innocence.

He was neither afraid of the sexuality of the models nor of his own libido, and so his nudes are not contaminated by the petty emotions that social oppression and mean-spirited moral condemnation encourage.

For centuries, sleep had been a way of alluding to sexual fulfilment and many of Modigliani’s models, especially the later nudes, are asleep. Those that are awake appear calm and unconcerned or have blank eyes and are lost in an introspective world, undisturbed by the observer.

Modigliani is primarily interested in the shapes of the bodies of the models, not their characters, and the blank or closed eyes only serve to emphasise this disengagement. Blank eyes not only also represent the inwardly-directed gaze and introspection that fascinated Modigliani, but also comment on the nature of voyeurism and observation.

For instance, unlike Edgar Degas (1843-1917), who almost always tried to show his models as unaware that they were being watched, Modigliani sometimes makes it clear that the model is looking back at the viewer, as does the model depicted in Nude Looking over Her Right Shoulder (1917).

Modigliani was also seeking to go beyond images of individuals to convey a timeless and eternal quality outside of everyday social morality and behaviour. This idea was inspired by the classical concept of beauty but also chimes with Cézanne’s abstraction and reduction of complex forms to their simplest essences. Chaim Soutine said of Cézanne, “Cézanne’s faces, like the statues of antiquity, had no gaze.”

Picasso, too, had looked away from the depiction of particular individuals in his studies of abstract African sculpture, hoping to find something more enduring in an image than the ephemera of one moment of one person’s life.

Modigliani’s depersonalisation of his images can also be seen as part of this artistic aim, especially evident in the portraits that he painted while in the south of France, which include twenty-five of Jeanne Hébuterne. He said, “What I am seeking is not the real and not the unreal, but rather the unconscious, the mystery of instinct in the human race” (Doris Krystof, Modigliani).

An Aesthetic Quest

Modigliani’s yearning for perfection in shape and form became an almost Platonic quest to find the essence of beauty beyond the attractiveness and sensuousness of the individual. He began to concentrate on balance, harmony, and continuity of form and to lessen the emphasis on heavy plasticity.

He wanted to combine the solidity of sculpture with a weightless luminosity of colour and an elegance of line. This aesthetic aim went far beyond the expression of the eroticism of any single figure.

The culmination of this endeavour can probably best be seen in his Seated Nude with Necklace (1917), Reclining Nude (c. 1919), and in Nude (1919). Modigliani’s skill as a colourist and his precision of line are both evident, especially in Reclining Nude.

The detailing of the breasts and pubic region is more restrained than in earlier nudes, inspiring a gentler but less fleeting erotic response. Standing Female Nude (c. 1918-1919) has a floating grace and the detailing focuses on her face. The swinging line and full curves of her breasts are anatomically accurate, while Modigliani’s mastery of line enabled him to use the fewest lines necessary to depict solidity.

By the end of his series of nudes he had mastered the depiction of the sensuality and attraction of the individual and had removed unnecessary idiosyncrasies to reveal only the abstract aspects of beauty.

Having explored sexuality on a personal level he looked for the transcendent desire beyond the individual response and was able to step back from the frenzied carnal intensity of his earlier works to create a less personal and thus a less evanescent eroticism.

His success in transforming the erotic energy and allure of one model at one point in time into an image that conveys the universality and endurance of human sexuality is perhaps Modigliani’s greatest artistic achievement.

Conclusion

Modigliani’s love of traditional Italian art and his view of himself as working within and developing this tradition meant that his nudes were not intended to be radical or confrontational.

However, he could not avoid his perceptions being affected by the avant-garde art that was being produced around him and he was inspired by similar influences as said art. This led him to draw together the ancient and the modern and the traditional and the revolutionary.

It was this blending of old and new, along with the intensity of his passion and his desire to express himself freely, that enabled him to create a new and unique vision. Despite the tragedy that often accompanied his own short life, his nudes are joyous and appealing and have remained some of the most popular in modern art.

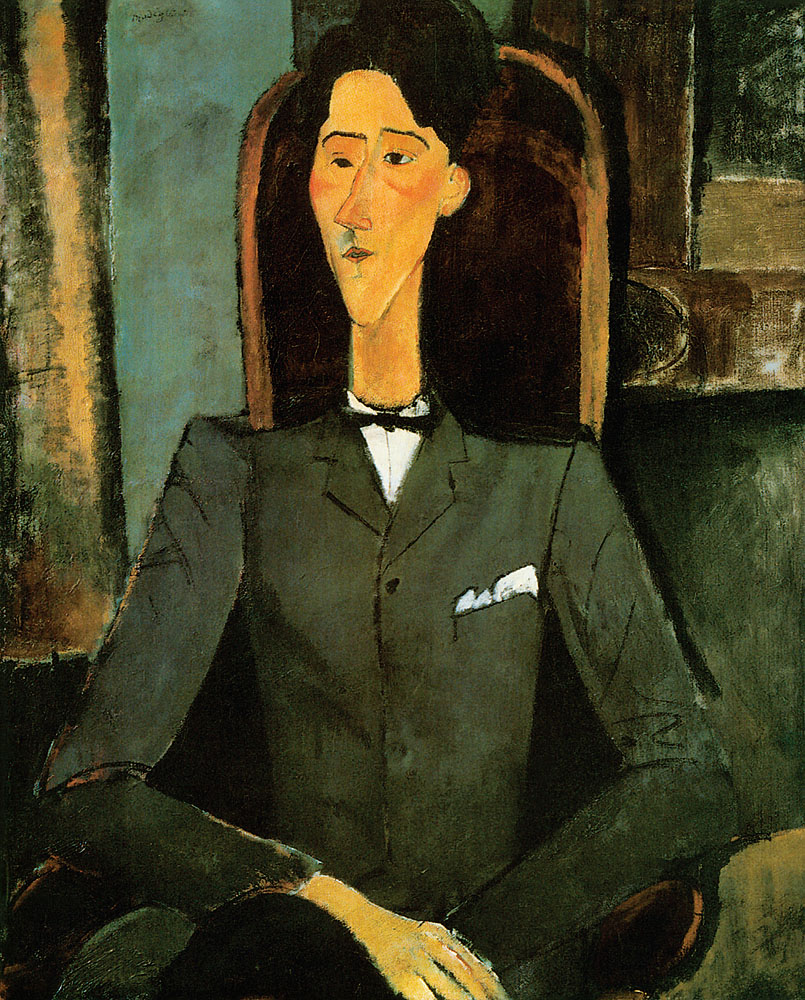

Jean Cocteau, 1916. Oil on canvas, 100.3 x 81.3 cm. Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, Inc., New York.