Introduction: In Search of Mondrian

Aldous Huxley once proposed an anthology of masters who created “Later Works”. He did not mean artists who lived long without ever departing from their youthful styles, but those who “lived without ever ceasing to learn from life.” To qualify for Huxley’s pantheon, the works an artist produced when middle-aged or elderly had to be significantly different from earlier ones.

Huxley mentioned the “astonishing” and often “disquieting treasures” among the later works of Beethoven, Verdi, Bach, Yeats, Shakespeare, Goethe, Francesca, El Greco, and Goya. To the artists on Huxley’s list we could add Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Picasso, Moore, and Mondrian.

In their later works, these artists were often thought to have fallen below the creations of their mature periods when, actually, they had moved on to attenuated, or expanded versions of their previous styles. Often, the late works could not be understood even by those whose tastes were formed by their mentors’ mature works, but only by followers in a later time. Piet Mondrian was surely such a master.

During his final three years and four months of life spent in the United States during World War II, he launched into a far less fathomable version of his consummate modernist oeuvre. With his final, unfinished painting Victory Boogie-Woogie the artist may have adumbrated Postmodernism, a style (or anti-style) that was to follow his death by some thirty years.

Yet, his late works are still relatively misunderstood, particularly in Europe. Frank Elgar, the French author of a popular monograph on Mondrian, found it unfortunate that he “did not resist the temptation to transmit to his ill-named neo-plasticism the joys so amply provided by American life”.

Elgar was referring to the usual interpretation of works done by the artist toward the end of his life in New York, as being literally descriptive of the city and the popular “boogie-woogie” jazz form. Mondrian’s chief biographers, the Belgian Michel Seuphor (a pseudonym for Ferdinand Berckelaers) and the Dutch Hans Jaffe, saw no diminution of quality nor discontinuity of theory in his late works; nonetheless, both men stressed their illustrative implications.

Farm on a Canal, 1900-1902. Oil on canvas laid down on panel, 22.5 x 27.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

Forest, 1899. Watercolour and bodycolour on paper, 45.5 x 57 cm. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

The artist was obviously stimulated by his new environment in America, which he had reached, so full of hope, on 3 October 1940. His immigration resulted from World War II, but the ideal that brought him to the United States reached back to World War I, when Mondrian first formulated a theory of his place in the modern world and a message for its future inhabitants.

By the advent of World War II, this idealism had become inseparable from his dream of America, which was where he thought the new world of future humanity would flourish. The artist saw more freely in this country, as he said Americans did, and the paintings began to change in keeping with his new vision. When he altered the colour and tempo of his new canvases, the feeling of continuous movement, or change, overcame the stasis of his former ones.

The final Boogie-Woogies were dynamic, indeed. They were a remarkable achievement for a man of Mondrian’s age – he died just prior to his seventy-second birthday. Yet, because the paintings do not seem to fit his standard set in Paris, they are thought by many to fall short of the Parisian mode. In these late works, however, can be seen both the inspiration of the artist’s new environment and the culmination of theory that he had developed long before coming to this country. I have therefore considered the paintings according to place and philosophy, hoping the reader will not think of these as being mutually exclusive.

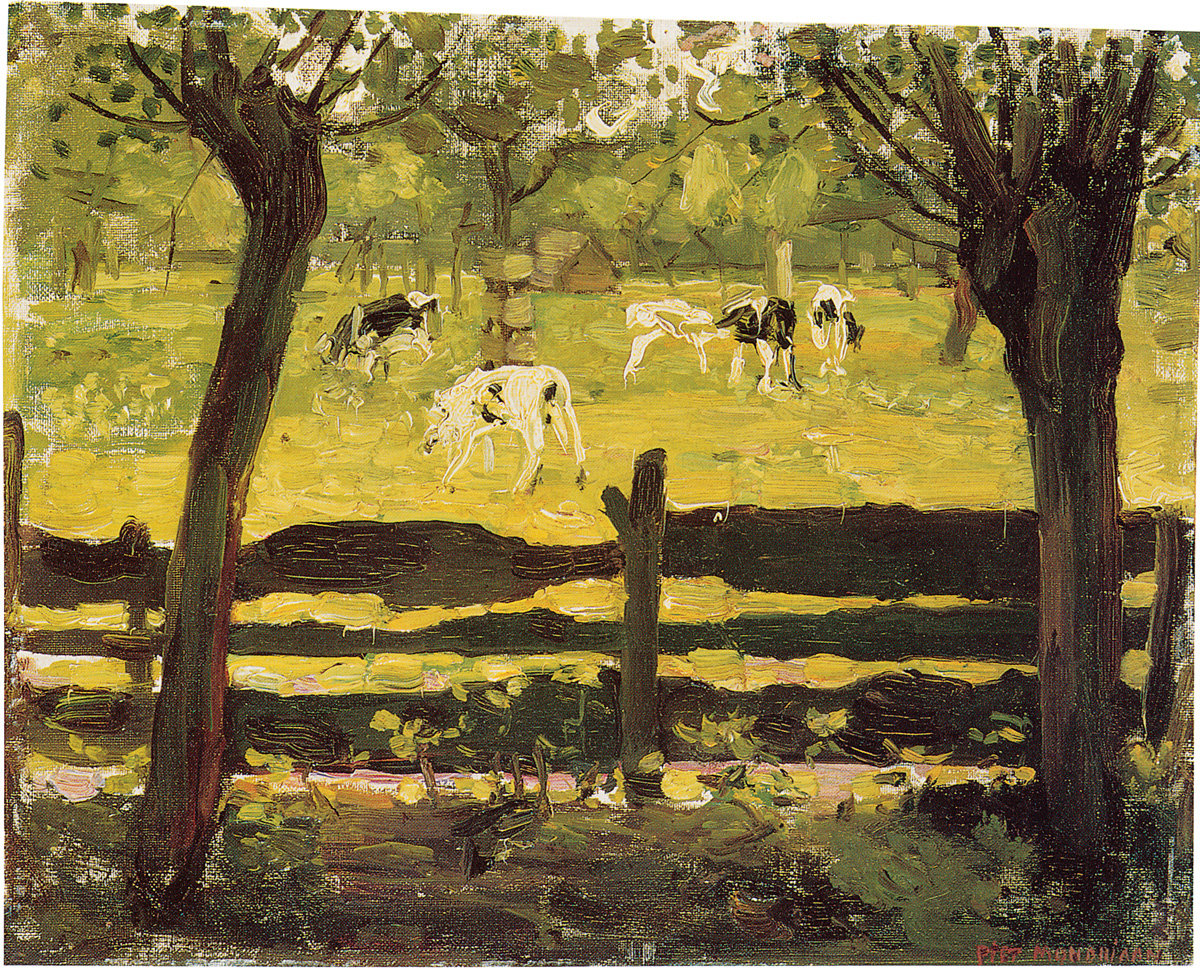

When examining Mondrian’s roots in late 19th-century Holland as they contributed to his artistic formation, I did not attempt to be comprehensive. This was because the artist’s realistic period in Holland and his Cubist and De Stijl periods in France and Holland had been treated authoritatively by Jaffe, Seuphor, Welsh, and Joosten. My study overlapped theirs only because it was necessary to relate Mondrian’s De Stijl theory to his earlier works in order to demonstrate the continuity that led to his final achievements in America.

Whenever possible, I found it advantageous to allow the artist to speak in his own words. His writings had seldom been used because, as translated from Dutch into other languages, they were repetitious, convoluted, and imprecise, and thus difficult for readers to follow. Nevertheless, Mondrian had found it imperative to write and had made a laborious effort to explain himself. Harry Holtzman gave me a copy of the manuscript that he and Martin James were preparing of the writings for publication, so I have used this version in excerpting some of the artist’s statements. Especially when Mondrian’s words clarified his intentions better than anyone else’s, I thought he deserved to be heard.

Next, I looked into the circumstances that brought the artist to America and their impact on him, as well as on those who understood his significance. In a middle section that is pivotal to the entire study, I turned back to Mondrian’s theory, this time in terms of its pragmatic relationship to his work. Also, I showed how his paintings differed from the amalgam of European styles followed by the American abstract artists until some of them began to understand his logic and to be affected by it in individual ways.

When treating Mondrian’s followers, I first turned to the few artists who were closest to him and, then, to the larger number who were indirectly but irrevocably changed by contact with him. I had the opportunity to meet numerous associates of Mondrian or his followers, chiefly in the late 1960s (although some of the friendships continued beyond that time).

The timing was fortunate, because most of them have since died, including: Alfred Barr, Ilya Bolotowsky, Fritz and Lucy Glarner, Carl Holty, Harry Holtzman, Hans Jaffe, Sidney Janis, Lee Krasner, Richard Paul Lohse, Kenneth Martin, Alice Trumbull Mason, Henry Moore, George L. K. Morris, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Winifred Nicholson, Silvia Pizitz, Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, Emily Tremaine, Charmion von Wiegand, Vaclav Vytlacil, and Paule Vezelay.

Woman with a Child in Front of a Farm, c.1894-1896. Oil on canvas, two parts, both: 33.5 x 44.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

Carl Holty was the most informative. Although he never followed Mondrian’s orthodoxy, he understood it fully and helped me to understand, too, not just the theory but how to see the older artist’s paintings. Under Holty’s tutelage, I began to view artistic space not just as a concept, but as a concrete reality, which is exactly the way Mondrian intended it to be. The elder artist’s influence on Holty was of the marginal type that he passed on to the Abstract Expressionists; nevertheless, I gained much information and understanding from Holty on Mondrian himself, as well as his influence on other American artists.

I visited Holty in two of his New York studios. His paintings – the ones leaning outside their racks for him to view and the one always in progress on a horizontal platform - had a lovely glow induced by the artist’s command of colour. The sense of surface and underlying form that controlled the tendency to lyricism in his late work had come from Mondrian, he said, but the colour was his own and to Holty’s gratification, the older artist admired openly the colour in one of his paintings at a New York exhibition.

At first, Holtzman would not comment on his own work, of which there was only one example publicly available, at the Yale University Art Museum. Finally, he consented to discuss the four works that he showed in the exhibition of “Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927-1944,” hung at the Whitney Museum in the summer of 1984. In the summer of 1985, I visited the artist’s home in a reconverted barn in Connecticut. He was proud of the current work that could be seen in his spacious top floor studio – work that was “standing on the brink of history,” he said. This was because in the new, “open reliefs,” he had integrated painting, sculpture, and architecture, which was an unrealised ideal of Mondrian’s. At age 73, Harry Holtzman was ready to emerge from his mentor’s shadow. He died at age 75, however; his work was shown posthumously in New York City, in 1990.

I had met Ilya Bolotowsky years before, when he came from Black Mountain College to lecture at the University of North Carolina. Twenty years later, he remembered the time we met in Chapel Hill and invited me to meet him in his mother’s New York City apartment. He and his wife Meta lived at Sag Harbor, near where the artist taught at Long Island University at Southampton. The apartment, on Thiemann Place, was a convenient point from which to tour the galleries on weekends. The artist’s mother was elderly by that time (the late 1960s) and had to pull herself around the rooms by way of a railing attached to the walls. Nevertheless, she stood by Bolotowsky’s side when he sat at the table and inquired deferentially from time to time: “What will the man have?”

His long grey moustache that moved rhythmically with an unflagging current of words provided a distinction that belied Bolotowsky’s short stature. I could imagine him in the scarlet greatcoat and high fur hat of a Cossack, wielding a saber from horseback. What infinite patience he called upon to explain the subtleties of Neo-plasticism, however. He allowed me to photograph his work of that time and, later, at one of his exhibitions at the Borgenicht Gallery. I last visited the artist in his loft on Spring Street and photographed him among his columnar constructions that were in all stages of completion. We ascended to the loft in an ancient elevator, the one that was the scene of his fatal accident less than a year later.

My meeting with Fritz Glarner was shortly after a near-fatal accident had sent him to the Rusk Rehabilitation Centre in New York City. He was there for more than a year while recuperating from a brain injury suffered during a storm when he was thrown against a bulkhead as the artist and his wife were returning on the liner Michelangelo from one of their annual trips to Switzerland. Lucy Glarner agreed to my visits, which she thought would be a diversion for her husband while he was in the hospital. She did most of the talking, because he had difficulty in articulating his thoughts.

Glarner was withdrawn most of the time, but he became animated when his theories and works were mentioned. He seemed to think more clearly when he tried, with the help of his wife, to discuss them. After he was well enough to return from Rusk to their studio home on Long Island, the artist was able to continue a limited amount of work, even though he was in a wheelchair and completely dependent on his wife. The Glarners later moved permanently to Locarno, where both of them died, Fritz preceding his wife by only a few years.

Another follower, Charmion von Wiegand, was a delightful resource person. She could talk endlessly on Mondrian and loved to recall his little jokes that she would deliver with her lips pursed in imitation of a Dutch accent.

Farm with Line of Washing, c. 1897. Oil on cardboard, 31.5 x 37.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

Grove of Willows on the Gein, c. 1902-1903. Oil on canvas, 54 x 63 cm. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

It was obvious that she had been affected personally as well as professionally by the artist. He had a strong physical appeal for her, although he was a “touch-me-not” type of person, she said. Von Wiegand spoke of Mondrian’s (not at all effeminate) “fineness and delicacy” of gesture and of his piercing eyes that he kept averted, “because they had the power of a whiplash,” she said.

By the time I knew her, von Wiegand had digressed far from the older artist’s direct influence, albeit in a direction that actually stemmed from his interest in Theosophy. She had studied Madame Blavatsky’s writings and had become interested in all of the Eastern theological and philosophical sources that led that amazing woman to found Theosophy.

The brilliant colour and variety of imagery in von Wiegand’s late work was influenced by the abstract art of Tantric Buddhism. This was palpable in a 1970 exhibition of her work at the Birmingham Museum of Art.

Before she died, von Wiegand was honoured by the National Women’s Caucus of Art; she was puckishly senile by that time and refused to attend the ceremony. Her award was accepted by one of the Nepalese Buddhists whom she had befriended and who took care of her in her final illness.

Burgoyne Diller died in 1965, so I did not have the opportunity to meet him. My interest in the artist dated from a 1963 exhibition of his work that was organised for Birmingham-Southern College by Silvia Pizitz, one of his chief patrons. I had several conversations with Pizitz about his work, as well as one with Kenneth Preston, who had organised a posthumous Diller exhibition for the Newark Museum.

On two occasions, I was able to visit Diller’s home in New Jersey. With the help of his widow and her son, I photographed the artist’s work before more than a few of his paintings and sculptures (no drawings at all) were brought out of his home and exhibited in New York City. The leads that I followed on Mondrian beyond the immediate followers took me in many fascinating directions. Eventually, I interviewed some of the most important American Abstract Expressionists, such as Ad Reinhardt, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and Lee Krasner.

I corresponded with Charles Biederman and met many other artists, historians, critics, collectors, and dealers in this country who were associated with Mondrian in one way or another. Among them were: Leon Polk Smith, Alice Trumbull Mason, George L. K. Morris, Kenneth Noland, Alfred Barr Jr, Robert Welsh, Milton Brown, Sidney Janis, and Rose Fried. At her gallery, Rose Fried introduced me to Marcel Duchamp, but I was too awed to ask him a single question - I wondered if the same thing would have happened had I met Mondrian.

One of the most helpful of the dealers was Arnold Glimcher, who had been my student at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in the late 1950s. Founder of the Pace Gallery in New York City, Glimcher became my mentor as he interpreted the abstract art that followed Abstract Expressionism in the 1960s. He also introduced me to people who were important to my quest, such as Emily Tremaine, owner (with her husband Burton) of Mondrian’s Victory Boogie-Woogie. I met Michel Seuphor and César Domela in France; Alan Bowness, Nicolette Gray, and Kathleen Stephenson in England; and Hans Jaffe, Enno Develing, Joop Joosten, Robert Oxenaar, and Piet Zwart in Holland. One day, I spent an afternoon and evening in Amersfoort, despite Professor Jaffe’s objection that it was “only a little Dutch Protestant town,” because I wanted to see the place where Mondrian had spent his first years of life.

In England during the summer of 1978, I attended a recreation of the original “Unit One” exhibition at the Portsmouth Museum of Art. Alan Bowness (then Reader in the History of Art at the Courtauld Institute - later Director of the Tate Gallery) had told me about the exhibition, which was important for the development of abstract art in England. Bowness also suggested that I visit Winifred Nicholson, with whom I spent a most charming afternoon.

The granddaughter of an earl, Nicholson still lived on her ancestors’ land. The old Norman wall ran along the road in front of her stone cottage in Cumberland. She invited me to have tea with her and her grandson in the kitchen where, over sun-ripened tomatoes and brown bread spread with wild honey, we talked about how she helped Mondrian flee Paris for London when war threatened in 1938. Nicholson gave me a copy of an eloquent piece she had written on her experiences as a young art student living in Paris during the years between the two world wars.

Truncated View of the Broekzijder Mill on the Gein, Wings Facing West, c. 1902-1903 or earlier. Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard, 30.2 x 38.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Still Life with Plaster Bust of G. Benivieni, 1902-1904. Oil on canvas, 73.5 x 61.5 cm. Groninger Museum, Groningen.

Nicholson also recounted the frustrating reactions she received to abstractions she painted after she had returned home to a largely unreceptive England. She never stopped painting, though. The results were all around us on the walls of her house in Cumberland, along with her husband Ben Nicholson and their children and grandchildren.

Paule Vezelay was just as interesting a person and energetic an artist as Winifred Nicholson (although neither acknowledged the other). Ronald Alley, curator of the Modern Foreign Collection at the Tate Gallery, showed me one of Vezelay’s works and suggested that I visit her which I did in the artist’s tiny townhouse in the London suburb of Barnes. Vezelay’s studio included almost all of her works: the paintings done in England until the late 1920s when she settled in Paris where she became one of the original members of Abstraction Création, and the ones done after her return to England at the start of World War II.

The artist’s stories, of Paris between the two wars as well as of England during both wars, were gripping. She had shown great courage during World War II by organising a women’s group that launched air balloons (“the size of a house,” she said), to intercept low-flying bombers. From Vezelay, I learned what it must have been like to live through the terrible bombings, which Mondrian also endured when he lived in Hampstead.

Another glimpse into Mondrian’s life during wartime came from the Henry Moores who told about their memories of Mondrian in Hampstead. They had moved into the mall studio that Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth abandoned as they fled from London during the bombings. When that studio was bombed, in the same raid that destroyed the house next door to Mondrian’s and brought on his decision to depart for America, the Moores left the city, too. They rented part of a farmhouse at Much Hadham, a village north of London. Later, they bought the farmhouse and all of the surrounding land, which Moore turned into a national sculpture park of his work for the British people.

At an earlier time, I went to Hampstead to photograph Mondrian’s house and, behind it, the studio mall where the Nicholsons had lived. The only one of the Hampstead pre-war colony still there when I visited was Kathleen Stephenson. She told me how all of the members of the colony had revered Mondrian. The Nicholsons had tried to get him to leave London when they did, but he was only persuaded to leave, later, by the severity of subsequent bombings. By that time, most of the other Hampstead artists had dispersed. I followed the route taken by the Nicholsons to St Ives, but by the time I got there, Ben Nicholson had long since left and Barbara Hepworth had died.

Among other abstractionists of the post-war generation in England whom I met were Victor Pasmore and Anthony Hill. Each told me about the period after the War when experimental art collapsed and they worked alone and unsupported until stimulated by Charles Biederman’s Art as the Evolution of Visual Knowledge. Guided by Biederman’s rationale for the development of abstract art to Mondrian and beyond, they began the abstract movement in English art. I talked by telephone with Kenneth Martin, another artist of this movement, and in the summer of 1985, photographed his posthumous exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery, London. Also, I talked by telephone with Sir Leslie Martin, the architect who became a spokesman for the modern English movement.

In Switzerland, I met Max Bill and Richard Paul Lohse, who followed a branch of Constructivism called Concrete Art that finds its roots in Mondrian and Malevich. Bill brought to my hotel many catalogues of his work and articles about his activities, but Lohse was wary of me until he realised that I understood the background of his distinctive style. Then, he discussed freely the glowing paintings in his studio. It seemed that wherever I met artists who were influenced by Mondrian, they received me graciously, as if anxious to share their knowledge with someone of equal devotion to their master and their cause. We seemed to agree tacitly that all of our lives had been touched, perhaps even directed, by that remarkable man.

At the Lappenbrink, Winterswijk, c. 1904. Canvas laid down on board, 33.5 x 45 cm. Private collection.

Calves in a Field Bordered by Willow Trees, c. 1904. Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard, 31.5 x 39 cm. Private collection.

The French Mill on the River Gein, c. 1905-1907. Oil on canvas laid down on board, 35 x 51 cm. Private collection.

Exhibitions of more recent years, such as “Pier + Ocean,” held in 1980 at the Hayward Gallery in London and the Kroller Muller Museum in Otterlo, and “Constructivism and the Geometric Tradition and Concepts in Construction: 1910-1980,” which travelled to several American institutions in 1979-1980 and 1983-1985, have presented Constructivism (usually interpreted by then to include Neo-plasticism) as a world-wide phenomenon.

I had turned to Europe whenever it seemed appropriate, because the international phenomenon that Mondrian represented could not be confined to American shores. Nevertheless, since the culmination of his life and art took place in the United States, I focused these pages on his American years and his subsequent influence in America. My interest in the critical study concentrated on the symbol as well as the changing attitudes toward the artist as his name became something of a household word. On the popular level, either his name or a logo fashioned from the most obvious characteristics of his style turned up on everything from a birthday card to an advertisement for a California hotel so “contemporary” in its appointments that it was named “le Mondrian”.

Even in art publications, the artist’s influence on design was emphasised long after he died. Over the years, however, as his standard in painting was invoked to measure or judge all subsequent American movements that either stemmed from his style or ran counter to it, Mondrian changed in the literature from a mere designer to a classical artist. Eventually, he became the lodestone of Modernism.

Only now can it be seen that in his “later works,” Mondrian was more. In these works, he created the paradigm for extending the rules of art when they can no longer carry the artist’s message. Every generation needs its examples of intellectual and creative courage. I believe that Piet Mondrian is such a model for artists of his adopted country.

A final note. I consider there to be a great deal of mythology surrounding Mondrian, with reference to his “spirituality,” his personality, his working methods, his relation to followers and theirs to one another. I have attempted to cut through this mythology by presenting a holographic image of the artist, as represented not only by his own statements and writings but by the views of many people who were close to him, or who have interpreted him rationally. The spiritual motivation to his art I have discussed in the first chapter, but then I have let it alone.

There are two reasons for this: one, his connection with Theosophy has been thoroughly treated by Jaffe and Welsh, particularly the latter; and two, I do not believe that Mondrian translated his spiritualism directly, that is, illustratively, into his work. There is no doubt that his original impetus for adapting abstractionism was motivated by spiritualism, but it was also motivated by logic. After achieving “the style,” I believe that the artist allowed it to follow, with variation, its logical course. Never would I agree that he intended to illustrate religious symbols, such as cosmic eggs or crosses. None of his writings nor any evidence of his working procedures would support such an idea.

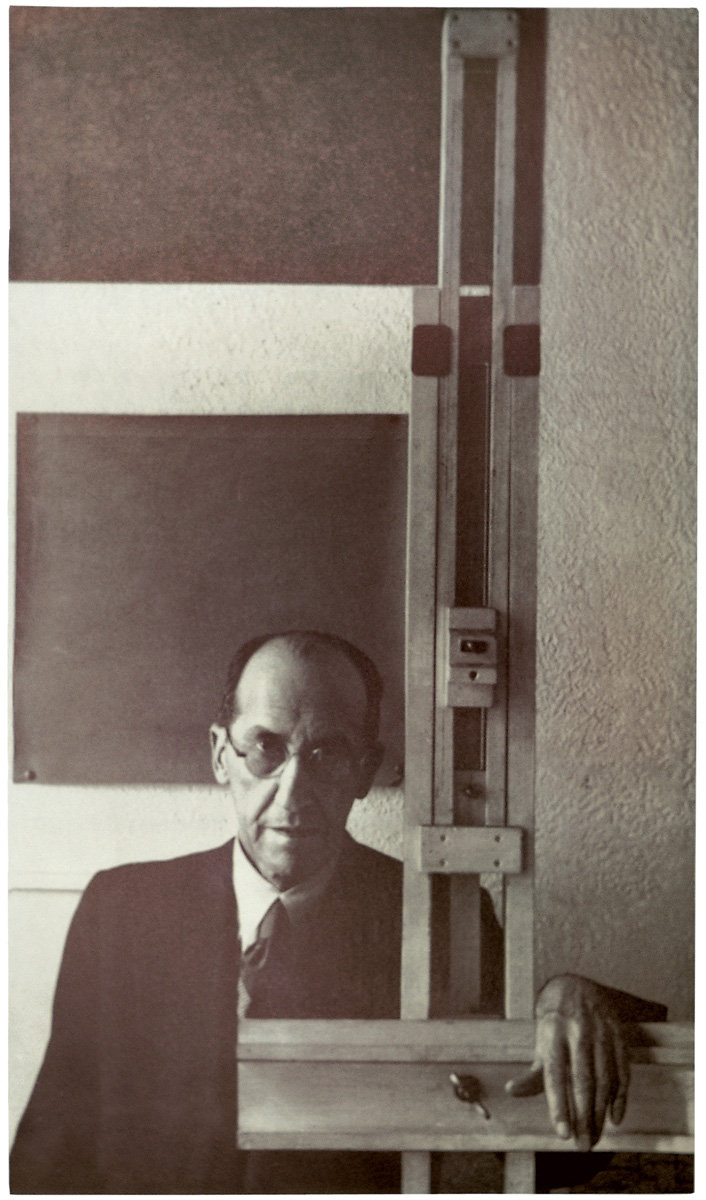

I do believe that Mondrian absorbed specific spiritual tenets into an aesthetic system which he practiced in the same way that any artist approaches a canvas, with a combination of pragmatism and intuition. He might have meditated before making a painting (one photograph does show him in a meditative stance), but his studio methods were those of an aware artist, not one in the throes of an out-of-the-body experience. I hope to have demonstrated this by lengthy discussion of his working methods.

Additionally, I have chosen to stay clear of the petty jealousies and in-fighting that went on among Mondrian’s followers. Perhaps because he gave the appearance of being vulnerable, those who were closest to the artist felt protective of him, which caused some strong-arming and jockeying of position among them.

Mondrian seemed to have been above all that kind of pettiness, however. In a human sense, he was grateful to those who were most helpful to him and rewarded them accordingly. The fact that some associates benefited more from the association than others need not imply calculation on his part nor on theirs. At any rate, since such stories came to me in hearsay, I preferred to ignore the insinuations that might be drawn from them. Of far greater importance, I think, is the artistic inheritance.

In the words of Carl Holty, only one of the artist’s friends and artistic legatees, we are all his “heirs, without equity”.