The Russian Painters of Water

Water and its Symbolism

Water is key to the formation of the world and human society. It is one of the four primeval elements from which, people once believed, the whole world was made. Water certainly was – and still is – the principal force whose eroding power forms the features of the land over eons of geological time. Today it separates the earth’s continents from each other. The first human settlements were made near water, beside lakes, rivers and sea shores. According to various ancient beliefs, water once drowned the whole world, and then receded to allow humankind to make a fresh beginning.

Water is still used to baptise people into various religions. It is the giver of life and the bringer of death. Without it the human body survives for just two days. It irrigates food crops and yet it may impartially obliterate thousands of people in a single tsunami. Frozen as snow and ice, it vanquishes armies. As fog it can make even brave sea captains fearful.

Water embraces all extremes from limpid tranquillity to cataclysmic violence. It is therefore not surprising then that water has been a pervasive element in art, architecture, and landscape design. It has been used to symbolise the source and sustenance of life.

It has served as a representation of nature’s mysteries, as a physical barrier and boundary, and as sparkling decoration. Painters have been fascinated with its misty, reflective qualities, and its ability to underline and sometimes represent a whole range of emotions.

As marsh and lake, mist and snow, puddle and ocean, waterfall and driving rain, deadly flood and slow moss-banked stream, it has an extraordinary diversity of forms. But because it is contained and defined by the very land it has shaped, it can never exist entirely in isolation. Water always needs a physical or metaphorical container: it can exist meaningfully only within a context. For these reasons, the representation of water in painting is most frequently as an element of nature, implying that it is best understood in terms of landscape painting.

But this is not exactly always the case because water is also frequently employed in a symbolic way. In Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, for example, the iconography of the myth demands that the sea be present because that is where Venus has sprung from – although in terms of composition the sea serves as an almost heraldic background device.

In Curradi’s Narcissus at the Source, it is only a small part of the painting and yet we know that it is the water that initiated the whole process which leads the young man in the most extreme of transformations from human to vegetable form. In the Curradi painting it is not only the water but also the landscape that is an adjunct to the painting of the main figure.

But it is in paintings of nature – landscapes or seascapes – that water is deployed most expressively, whether it is in the glowing landscapes of Claude Lorrain, or in a painting such as Arkhip Kuindzhi’s The Birch Grove.

In this, scarcely differentiated from the meadow to each side, the stream is used as a compositional device to lead the viewer’s eye into the centre of the painting to create the extraordinary sense of depth which astonished the artist’s critics.

In the great range of sea paintings by the prolific Ivan Aivazovsky, it is significant that he chose the sea as the setting for his almost abstract The Creation of the World. Here a mysterious red magma boils in the middle of an uncertain black cloud on the face of the waters seething vapour, with a febrile sun breaking through the cloud to cast a dim light on the heaving waters. This is God moving on the face of the Deep.

In Isaak Levitan’s Beginning of the Spring, three forms of water – cloud, river, and snow – are (apart from the brown branches recently released from their icy covering) the sole visual components of a painting to do with awakening and, perhaps, regret. And there are, as we shall see, many other variations in the use of water that painters have developed.

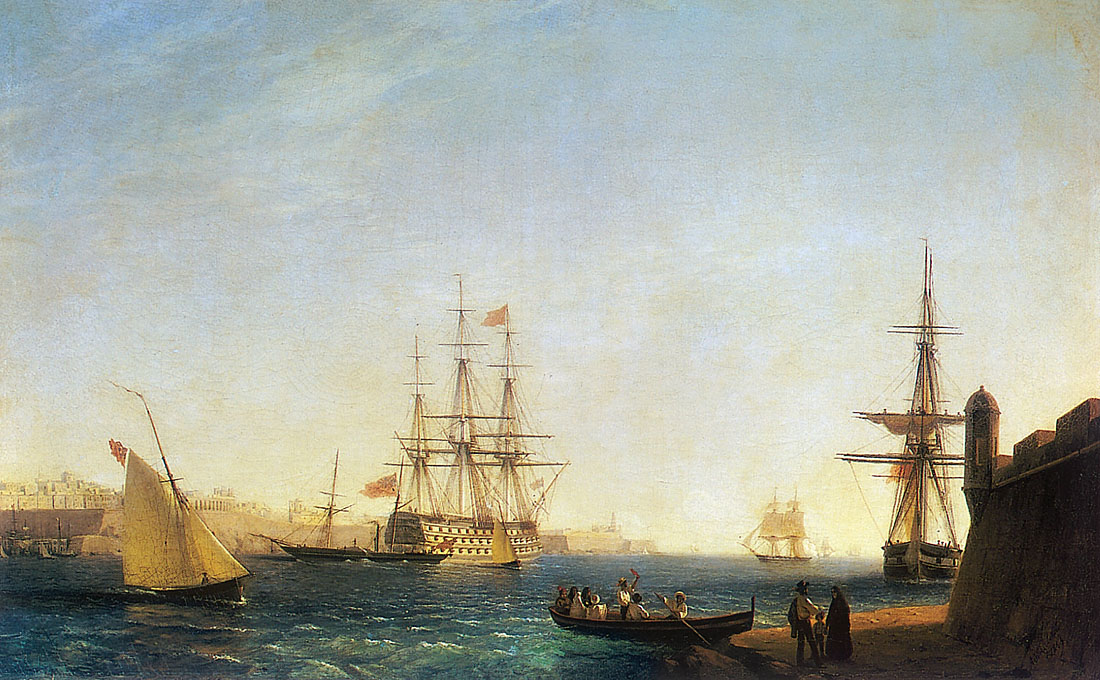

Port of Valletta in Malta, 1844. Oil on canvas, 61 x 102 cm. The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

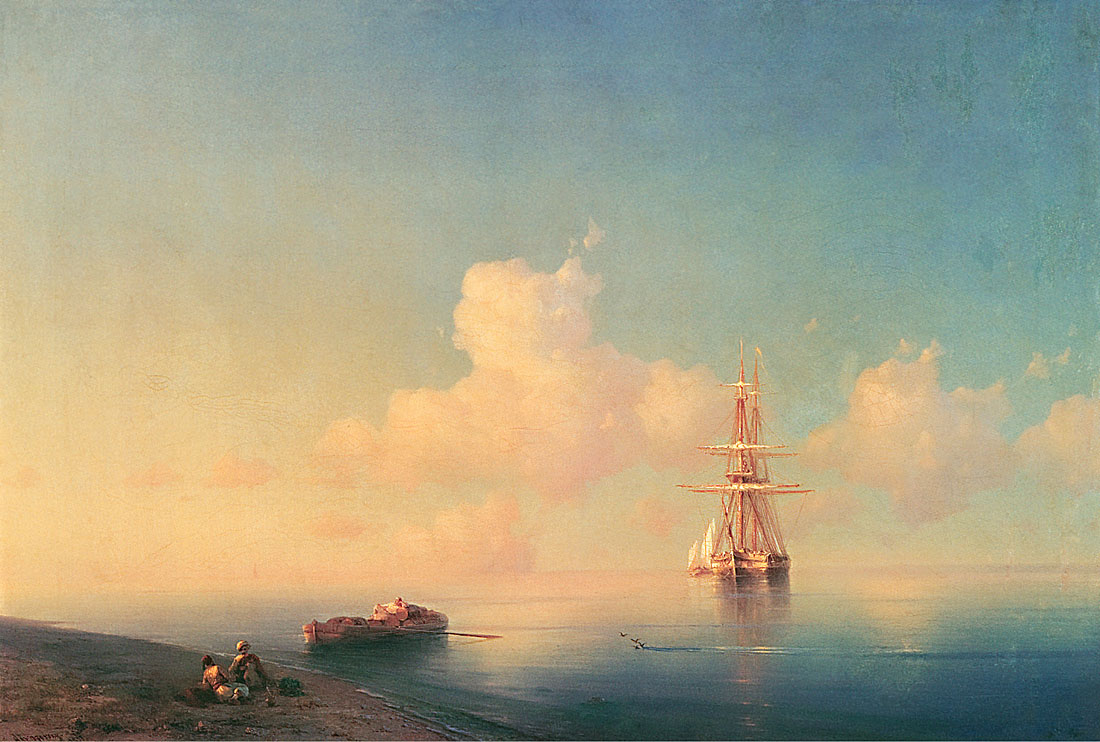

View of the Venetian Lagoon, 1841. Oil on canvas, 76 x 118 cm. Peterhof State Museum-Reserve, St Petersburg.

Levitan, Kuindzhi and, in a different way, Aivazovsky painted water with a peculiarly Russian eye. They are, as it happens, painters of the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century. One of the reasons Russian paintings of waterscapes and landscapes are of a relatively late date is that from the beginning of the 18th century Peter the Great and almost all of his successors in that century forced the Old Russia into a western mindset.

Russian art was entirely derivative of European models, and at first largely filtered by a Prussian vision, because Peter had brought in masters from Germany to teach aspiring Russian artists the ways of the West.

As a result, the nation’s artists were encouraged to think of themselves as part of the European mainstream, and were given grants to live, observe, and paint abroad for long periods of time. But at the beginning of the 19th century, with a new western interest in landscape and landscape painting, Russian artists began to both value and encourage the painting of nature, mountains, and water.

At first this was landscape viewed through the filters of a western-trained eye and consisted mostly of idyllic European scenery. But by the end of the century, Russian painting of water and land had become to do with the Russian landscape and identifiably took on a uniquely Russian character.

The country has the Pacific Ocean to the far east, and to the west is the Baltic Sea, with its gateway St Petersburg and the naval port of Kronstadt. South is the warm Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, with their resorts and trading ports fed by the great, broad waterway of the River Volga, which bisects the country into the East and West Empire. To the north, beyond the great wastes of the Siberian tundra, are the cold seas that form the mostly frozen Arctic Ocean. During the long winter, as Napoleon and Hitler discovered to their cost, much of Russia is frozen over.

Russia is geographically defined by its water in all of its three physical states: vapour, liquid, and translucent solid. The brutality, manic depression, melancholy, and gloom, which in many ways seem to typify the Russian national character, surely stem from a collective agoraphobia engendered by the country’s grim winter climate of rain, mists, fogs, snow, and ice. This is of course an oversimplification, for the south of Russia has a relatively equable climate – as the paintings of Aivazovsky, who spent most of his life in the Crimea, nicely demonstrate. And the spring, summer, and autumn could be delightful, as many of the painters of the late 19th century discovered.

But people need stereotypes, and the image of Russia held by foreigners and Russians alike has largely been of melancholy, tragedy, and callous rawness among those frozen rivers; damp, fog-bound cities; and ice-locked seas.

Even before Peter the Great built his new capital on the Neva, Russia’s rivers, lakes, and seas had formed a crucial transport network for the pastoral and often nomadic Russian people. In the late 19th century, Russia was not only a huge country, but still an essentially rural empire in which the boundless forests and plains were crisscrossed by streams, rivers, and lakes which were ever mobile. They changed shape and colour as the seasons changed. Indeed there is a Russian Orthodox ceremony known as The Consecration of the Waters at Epiphany. The Volga, one of a group of great continental Russian rivers, is not merely an extremely long and broad waterway. It holds a special place for Russians as a massive artery that feeds the country’s very heart, ranging from the wintry extremes of the north to the soft pleasures and seas of the south.

So Levitan, Kuindzhi, Aivazovsky, Arkhipov, and Repin, to name but a few of the great Russian painters of water, were not only celebrating a major feature of the visible landscape they knew, loved, and so obsessively painted but were also celebrating an incredible gamut of emotions and moods. These range from stark terror to peaceful tranquillity, from deep sorrow to exalted musing, and from delightful contentment to uneasy foreboding.

Water in Russian Cities

As a serious artistic activity, Russian painting really dates only from the 19th and 20th centuries. As the Russian Symbolist poet Alexander Block put it, “Russian culture is a combination of cultures, we are a new country”. Block’s new country was actually synthetic and coldly calculated – created at the beginning of the 18th century with Peter the Great’s westernisation of Old Russia. This had often been carried out with great brutality. And in some ways so too had Peter’s introduction of western culture, art, and architecture.

Russian society was originally tribal and backward, its art either primitive and decorative, or religious. Then it was suddenly faced with the highly sophisticated art and architecture of the West. Peter’s new capital, St Petersburg, was shaped as a model of the ideal European city, a kind of Venice or Amsterdam of the North, built on what had been the swampy delta of a river flowing into the Baltic Sea. And it was built by a man whose first love was the sea. Apart from its symbolic and political function, the new city was to be effectively a living textbook of the new western architecture, art, and culture, set like jewels on the lid of a box floating on the waters of the Neva.

Begun in 1703, with the young Swiss-Italian Dominico Trezzini as Peter’s architect in residence, St Petersburg had advanced just enough in 1712 for the Tsar to move his court there, although most of the buildings were still timber and arranged like a “heap of villages linked together”, as a Hanoverian diplomat described it in 1714. Peter had been impressed by the canal facades of Amsterdam, and Trezzini did his best to incorporate this visual obsession in his early designs.

In 1716, J. B. A. le Blond, a student of the great French architect and landscape designer André Lenôtre, took over Trezzini’s mantle and began designing and constructing the early public buildings and palaces in the new European classical manner for both the city centre and its hinterland, where the great families of the court began to establish estates.

At Peterhof, 18 miles (29 km) west of St Petersburg, le Blond designed a series of huge gardens and parks incorporating massive waterworks for which a 15 mile (24 km) canal had to be dug. They were constructed in homage to the great Italian and French baroque landscape models. The new city was, as one modern commentator has put it, “an exotic plant in an alien land, with its symmetry and order, it was the symbol of Russia’s longing to catch up with the West”. Peter died in 1725 and one of his successors, Peter II, took the court back to Moscow immediately on his accession in 1727. In 1732 Empress Anna moved back to St Petersburg with her architect Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli, and recommenced populating it with classical buildings, including the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoye Selo. The European veneer was still thin even when Peter’s daughter Elizabeth seized the throne in 1741. She introduced a variety of accomplished architects who worked in the refined rococo classical tradition.

The Bay of Naples in the Morning, 1843. Oil on canvas, 67 x 100 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

The Battle of Navarino on 2 October 1827, 1846. Oil on canvas, 222 x 334 cm. F. E. Dzerzhinskii Higher Naval Engineering School, St Petersburg.

But it was 1762, with Catherine the Great’s ousting of her husband Tsar Peter III, that Russia really found itself having to become a European nation. Catherine was a passionate patron of the arts and a great builder of neoclassical architecture, especially at the Hermitage, whose walls she adorned with paintings of the great western masters: Raphael, Van Dyck, Teniers, Rembrandt, and Poussin, as further exemplars of the heights of European culture. By the end of her reign Russia had taken its place among the nations of Europe. Although St Petersburg became a symbol of the new Europeanised society and a case study of how to be European, it nevertheless took time for the capital to grow and it achieved its final monumental classical form only in the third decade of the following century.

St Petersburg apart, Peter’s westernisation of Russia had actually less to do with the arts than with technology and society. Just as St Petersburg was the work of more than a century, changing a society’s thinking took time and dedication, especially when the court was deeply suspicious and reluctant at heart to embrace the ways of the West – as was much of the rest of the country. In 1757 it was the Empress Elizabeth who founded the Academy of Arts in St Petersburg. Until then Peter the Great’s successors had welcomed European painters to the Russian court. But most of those who came were only minor figures, and Russian artists trained by them had little impact.

In the early years of Catherine’s reign and patronage of the arts she ordered that the best of the new Academy students should be given travelling scholarships to paint in the great art centres of Europe. Moscow’s College of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture was to be instituted almost a century later in 1843, and it too continued the pattern of providing travelling scholarships for its artistic talent.

The tradition of supporting young artists for three or four years abroad was to continue right into the 20th century. An early case in point is Karl Briullov, who in 1821 graduated from the Academy. He and his architect brother saw first-hand the work of the masters he had admired from afar in St Petersburg: Dürer, Correggio, Holbein, and the Italian primitives. In 1823 in Venice he found himself in front of Tintoretto and Titian, then in Florence he discovered Raphael and Leonardo, and later Rubens and Rembrandt. Here was an abundance of artistic riches, a kind of first-hand artistic smorgasbord. Unfortunately for the system, it was thirteen years before Briullov could be persuaded to return home and share his excitement and experience with his fellow artists.

If this policy actually produced very few original or significant painters during Catherine’s 37-year reign, it had at least laid the groundwork for the important Russian painters of the 19th century and gave the Russian artistic community easy familiarity with the works, techniques, trends, and fashions of the West.

This high level of determined westernisation meant that the European masters were as influential in Russia as they were in the rest of Europe. But there remained a major contradiction. Although the Academy sent bright young painters abroad to absorb the best of European attitudes and ideas, it had as an institution retreated at an early date into a resolutely reactionary and sterile official position. The depiction of classical, historical, and biblical themes – all in classical dress and with strictly allegorical intentions – remained mandatory if an artist was to be recognised by the establishment.

The Great European Landscape Precursors

Those European masters who influenced Russian art during this first phase included the great Canaletto, who in Europe had transformed topographical illustration into high art. Feodor Aleksiev’s View from the Petropavlovska Fortress of 1794 and his later View of the Admiralty of 1810, with their preoccupation with water and panoramic views, are so organised that they could scarcely have been conceived without a knowledge of the great Italians work such as, for example, The Bacino di San Marco on Ascension Day of 1732 and his The Thames and City of London from Richmond House of 1747.

Canaletto was a specific influence, but much more important for the whole of European landscape (and landscape design theory) were the great 17th-century masters Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), the pioneering masters of western landscape and water.

Claude was celebrated for his radiant depiction of landscape, often painted from studies sketched in the Roman Campagne, and Poussin was recognised for his brooding idealised Roman landscapes. Both were actually Frenchmen who had settled in Rome not far from each other on the Pincian Hill, and both are thought of as the fathers of true landscape painting. Cézanne, abandoning Impressionism, said that the landscape artist should aim at “Poussin painted from nature”.

Claude’s much-copied composition generally relied on a coulisse (usually a frame of trees through which the picture is seen), an extraordinarily delicate gradation of light to mark the divisions of the painting from a dark foreground through middle-ground to the misty distance of the background, and the golden glow of the sky. Invariably the boundary between the first two grounds is marked by limpid water, reflecting light into the centre of the composition.

For Claude, water was an almost essential, almost inevitable, element in landscape painting, whether it be the middle-ground lighting device of his Italian Landscape of 1648, or the turbid water of Morning in the Harbour of 1634. As we shall see, these were enduring images in the work of the expatriate Russian landscape painters and the great Russian sea painter of the latter half of the 19th century, Ivan Aivazovsky.

At more or less the same time in the Low Countries painters such as Rembrandt, Jacob van Ruisdael, Willem van de Velde the Elder, Jan Asselijn, Paul Bril, and Salvator Rosa were among those who depicted the rough natural landscapes of their native country, either as backgrounds to genre subjects or, revolutionary at the time, as landscapes in their own right.

These were all painters of the Baroque who had abandoned the clear religious and classical iconography of the early Renaissance and the linear and closed composition of their predecessors in favour of intensified light and shade; broad, almost impressionistic brush strokes; dynamic asymmetry in composition (rather than the formalised symmetry of even mid-Renaissance composition); and a choice of lay rather than religious classical subjects – especially landscape and waterscape subjects.

Under Catherine, Russia had become a European power which proved itself in contributing to the defeat of Napoleon in a great continental conflict. But in the 1820s Russian society took a look at itself and decided that there was something unique about Russia after all, that its customs and traditions had intrinsic value. Apart from the fact that most courtiers’ incomes were, unlike any other group in Europe, bound up in the ownership of human beings, there developed a belief in the need to acquire a national identity within European culture. At its worst this took the form of a heavy-handed nationalism in which Nicholas I demanded that the Russians become more Russian and that conservatism, autocracy, and patriotism were the proper and slow way forward, even if this effectively meant cutting off Russia from the ferment of ideas that were sweeping Europe.

At its best it encouraged Russian artists to be unashamed about being Russian and about painting uniquely Russian themes. Although this took some decades to get going, much of the painting of the rest of the century was, one way or another, imbued with this notion that Russia had of necessity joined the culture of the West but had a totally different origin whose qualities were worth celebrating.

In the early part of the 19th century the prevailing painterly styles of Europe had been a mixture of Romanticism and Classicism, and later Romanticism in its more ethnic genre and landscape modes. From the late 1850s onwards, Russian artists led by Perov began to reject Romanticism and the official cult of history painting in favour of a new Realism, which had for Russian artists a political agenda.

The Realism of Perov and his followers, and their preoccupation with the genre of peasant social reality, was to merge with the prevailing nationalism to support a new interest in Russian landscape painting. At first it was as the necessary accompaniment of everyday peasant life and later as a legitimate subject in its own right, as the young radicals eventually abandoned emotional arm twisting and as examples from Europe (such as the Barbizon School) gained popularity in painting circles.

Of course, landscape was a subject at the Academy. But it was not landscape as taught there, but the landscapes of Claude, Poussin, the Dutch painters, and the real-life Italian scenery that the Russian pioneers depicted. And it was not until such artists as Ivan Shishkin emerged from the new Moscow School of Art, Sculpture, and Architecture – directed in the 1850s by Alexey Venetsianov, who laid emphasis on sketching, painting, and learning from nature – that a truly Russian style of landscape began to emerge.

And it is not as if Russians had not painted pure landscape before this. Sylvester Shchedrin went to Italy on an Academy stipend in 1819 and acquired a reputation for his somewhat Claudian landscapes. Comfortable in Rome among his fellow expatriates, he declined to return to Russia and spent the rest of his life abroad.

His interest in pure landscape was engendered by the popularity in Europe of, among others, the English plein-air pioneer John Constable. And there was the local Italian Posillipo School of landscape. The young Corot is believed to have met Shchedrin in Rome and admired his work. The Russian painter very successfully exploited the subject of the Tivoli waterfalls outside Rome in a way that is reminiscent of Ruisdael and Salvator Rosa, and yet it is entirely fresh in its depiction of wonderful and lively nature. For the last fifteen years of his career he painted in Naples, still preoccupied with water, but now in the form of the Bay of Naples and the Mediterranean Sea.

Battle in the Chios Channel on 24 June 1770, 1848. Oil on canvas, 194 x 186 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

Russian Squadron on the Raid of Sevastopol, 1846. Oil on canvas, 121 x 191 cm. The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

Moonlit Night Beside the Sea. Constantinople, 1847. Oil on canvas (oval), 64.5 x 52.2 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

Shchedrin was important because he was a great influence on the leading Russian Romantic Karl Briullov, who made the European tour to study and paint in Rome or sometimes Paris, and like many young Russian artists visited Shchedrin. But Shchedrin was also important because of the success abroad of his landscapes which, quite contrary to the Russian Academy classicist line, are of real-life scenes whose function is to create a sense of atmosphere rather than provide allegories for life. At around the same time, a small group of Russian artists also worked on landscape themes, such as the brothers Chernetsov and Mikhail Lebedev (1811-1837).

Lebedev went to Italy on a stipend in the 1830s and followed in Shchedrin’s footsteps, painting the warm Italian landscape in the open air and with a more spontaneous range of colours than traditional Russian art rules permitted. His In the Park of the early 1830s is a sylvan scene, with still water reflecting the surrounding trees and the low evening sun filtering through, lighting the tree trunks and the lower canopies of leaves.

Another Russian contemporary was Alexander Ivanov, some of whose landscapes – for example The Bay of Naples of 1846 – are particularly well observed. A recluse, he too spent almost his entire career outside Russia and he was never very successful. But these paintings, whatever else they are, are not in any way Russian. They are simply painted by Russians. Except for Ivanov, most Russian painters of landscape were successful precisely because they worked in the European mode.

Like Shchedrin, Karl Briullov (1799-1852) developed a European reputation, crowned with his monumental work The Last Days of Pompeii of 1833, a significant example of Romantic classicism. Eventually returned to Russia, Briullov’s Romanticism manifested itself much more through portraiture than landscape. In fact his landscapes are still essentially Italian, although in his Portrait of the Artist and Baroness Yekaterina Meller-Zakomelskaya with her Daughter in a Boat of 1835, the water landscape serves as a visual device to isolate and define the closeness of the three protagonists. Only four years before in 1831 he had painted An Italian Family, in which a husband prepares a crib for his pregnant wife who inspects the coming child’s clothes. Beyond, through the open door, is a wide waterway in the valley below shadowed by the cliffs on the far bank. None of this is yet peculiarly Russian, although Nikolai Gogol maintained that Russian paintings emergence was due to Briullov. Censured on his return for choosing an inelegant model for his Italian Morning, Italian Noon, he replied firmly: “An artist becomes closer to nature by deploying selectively the techniques of colour, light and perspective. He has thus the right to reject conventional notions of beauty if that seems appropriate.” Here was the heart of the Romantic position and a clear rejection of his new critic’s dull adherence to conventional classical notions of beauty.

And here too was the end of the old slavish respect for classical values and understandings about what the proper subjects of painting could be and what the real purpose of painting might be. In many ways the real lead was about to be offered by a brilliant young graduate of the Academy, Ivan Aivazovsky, whose long life in painting from the 1830s to the end of the century was obsessively devoted to painting that greatest body of water on earth, the sea.

Bay of Naples on a Moonlit Night, 1842. Oil on canvas, 92 × 142 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

Battle of Chesma at Night, 1848. Oil on canvas, 195 x 185 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

Ponds, Lakes and Rivers

If Aivazovsky was the Russian master of the sea and its moods, Ivan Shishkin (1832-1898) was the master of the forests. One of his contemporaries wrote admiringly, “Shishkin is so faithful, has such deep affection for his native land that he has no rivals in portraying Russian nature and especially the Russian forest“. As a student at the Moscow College of Painting and Sculpture from 1852, and later at St Petersburg, he encountered paintings by such Russian artists as Ivan Aivazovsky, of expatriates such as Sylvester Shchedrin, and such European masters as Ruisdael.

Almost from the start of his course he began painting and sketching the local rural Moscow landscape. As his niece later recalled: “Shishkin was drawing views and landscapes the like of which no one had drawn before: a field, a forest, a river, just that – and they are as beautiful as views of, say, Switzerland.” Shishkin spent his scholarship years not in Rome or Paris but in Germany, Switzerland, and Bohemia.

On his return he was made an Academician on the strength of his painting abroad, and began drawing and painting Russian landscape. His mastery of both impeccable Realist technique and in evoking mood is exemplified by his An Old House on the Edge of a Pond. A sketch in sepia of an old semi-derelict stone farmhouse in an overgrown orchard with a pool that has somehow developed in a depression over the years, it is extraordinarily evocative of abandonment, decay, and age.

Shishkin’s magnificent obsession was with the coniferous forests of Russia. For the last thirty years of his life he painted practically no other subject, after exhibiting his Pine Forest in Viatka Province in the second Itinerants exhibition of 1872. If Aivazovsky, who started active work thirty years before him and died two years later, sometimes repeated himself, Shishkin contrived to bring a fresh eye to each painting. This was partly because he liked painting plein-air and, probably, because he saw the forest as a continually changing laboratory of information about the workings of nature.

In A Pine Forest in Viatka Province, Shishkin uses a forest stream as the main foreground element leading the viewer’s eye into the dark recesses of the forest past the clearing, which has been damaged by loggers searching for timber for masts. Bears play mournfully around a tree with a hive tied safely far up its trunk. In his Stream in a Forest, of two years before, it is as if the viewer has suddenly come upon the little scene, the still water disappearing into reeds to the right foreground, and in the background there is a hint of its source in a marshy sward, the middle ground following the old Claudian rule and reflecting the sky and surrounding foliage. Here the chromatic scale is deliberately kept narrow: browns and sepias, blacks and dark greens, and a series of rough surfaces contrasting with the hard reflecting surface of the water in the middle-ground.

From the outset Shishkin has realised the importance of including movement, however placidly it may be, represented by a shallow stream moving slowly over pebbles and little rocks on its gradual way to feed some larger waterway. Water is always important for Shishkin’s composition because it provides the necessary horizontal contrast to the vertical thrust of his trees. Shishkin returned to the same subject ten years later in 1880. The banks of this forest stream represent a cool haven from the hot summer sun streaming down the slopes in the background, beyond the grove which has grown up around the water.

Brig “Mercury” after a Victory over Two Turkish Ships, 1848. Oil on canvas, 123 x 190 cm. The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

The water moves slowly and has temporarily disappeared under rocks and moss by the time it reaches the foreground – the same device appears in the totally different painting of a decade before. In those ten years Shishkin’s palette has changed, the browns are redder, the greens more sun-drenched, and the viewer is made somehow aware that the tall straight trees of the grove are there because of the streams life-giving grace. The stream in the forest is a subject to which Shishkin returned again and again. In most cases these are not cascades, but gentle scarcely moving waters which, the viewer might well think, are there to provide a foil to the inevitable tall trees.

The Moscow School of the 1880s produced a number of painters, such as Arkhipov, Alexei Stepanov, Valentin Serov, and others such as Isaak Levitan, who wanted their art to be spontaneously expressive, to divorce their art from preconceptions and rules.

Serov, who as a student talked a great deal about the joys of life, went abroad immediately after his years at the Academy. He fell in love with Venice, absorbed the old masters, and on his return spent a great deal of time at Abramtsevo, the country estate of radical art patron and merchant Savva Mamontov. With fellow artists he painted the local scene and one theme in particular, the overgrown pond. As a subject it is interesting enough as a picturesque set-piece landscape theme, combining as it does foliage, sky, water, reflections, and possibly mist. But one suspects there is also a second agenda: ponds are overgrown because they have been neglected and in the latter part of the century many formerly noble estates could not cope financially with the freeing of the serfs and either went bankrupt or allowed their estates to decline.

Numerous Russian artists had been influenced by a painting of 1871, the second year of the Itinerants, by founder member Lev Kamemev. It is Fog: The Red Pond in Moscow in Autumn. It pays tribute to Claudian composition in its lucent light in the middle of the picture and the way the farther boundary of the pond merges through the golden fog into the sky.

The water, unbroken except by the silent reeds and scattered jetties, is suffused, saturated with an air of reposeful and unmistakably Russian sadness.

Vasily Polenov was a professor of landscape at Moscow. In his Lake Gennesaret of 1899, a special mood is evoked – a sense of wonder at the sheer extent of nature. The viewpoint is on a high crag overlooking the marshy preliminaries to the edge of the lake, which stretches across to the majestic line of low cliffs which themselves range left and right into the far distance, uniformly and unchanging.

Evening in the Crimea. Yalta, 1848. Oil on canvas, 126 x 196 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

View of Constantinople by Moonlight, 1846. Oil on canvas, 124 x 192 cm. The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

St George’s Monastery. Cape Fiolent, 1845. Oil on canvas, 128 x 202 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

One of Polenov’s students was Isaak Levitan, who at the end of the century had become one of the great painters of Russian water. Writing at the time critic Alexandre Benois said: “Levitan was not a Barbizon painter, nor a Dutch artist and not an Impressionist. Levitan was a Russian artist, but his Russianness does not lie in him having painted Russian motifs out of some sort of patriotic principles but in the fact that he understood the obscure charm of Russian nature, its secret meaning.”

Shishkin was the master of the forest and Levitan the master of placid open landscape, and especially water. His Lake of 1899, one of several such paintings, sums up his preoccupation with the painterly possibilities of water. The strip of land serves as a narrow middle-ground, a device to mark the transition between sky and its reflection in the deep foreground of water and vestigial reed bed.

Levitan’s special interest in painting water and rivers has a resonance in the rest of Russian painting of his time. For socially aware artists such as Ilya Repin, the great river Volga represented not only a picturesque setting for atmospheric paintings but also a location for depictions of powerful emotions of sympathy in the face of grim everyday life. His Barge Haulers on the Volga of 1873 is the seminal social painting for the Itinerants.

The sails of a decorated barge are draped negligently across the hold, and a steersman strains against the great tiller. The slight ripple along the bow is the consequence of the efforts of nearly a dozen ragged haulers, the burlaki, pressing heroically against the broad bands across their chests which spread the load transmitted from the top of the barges short mast. To the right, the rearmost hauler seems fit to collapse, his sole means of vertical support being the rope band, which half pinions his arms and shoulders, and yet supports him. The leading man’s face is full of both character and resignation as he leans familiarly into the load. These are people who have devoted their lives to the great river – and have had no choice and have no hope of doing anything else.

Yet half-way back in the middle of the canvas, painted in lighter colours, is a lad who grasps uncertainly at his bond and peers beyond the picture frame to some unseen source of hope.

For the leading historical painter of the Itinerants, Vasily Surikov (1848-1916), the river is the neutral setting for great thoughts, a kind of tabula rasa. His Stepan Razin of 1906 has the legendary hero being rowed up the Volga following a pirate raid in a boat laden with booty and, apart from the rowers and Razin, a celebrating crew. Razin reclines against the mast, scowling with the effort of planning the release from servitude of the Russian people. Perhaps the leader of a war flotilla, this is the only boat visible in the great whitish lumpy sweep of the mighty river whose far bank is a grey streak, the only thing differentiating river from sky. It is as if the boat itself represents Razin’s thoughts, looking backwards but surging forwards in a grey uncertain world. This exactly matched the state of Russian painting at that moment, a few years into the century.

Radical 19th-century Russian painting often carried an underlying anti-clerical message. But in the search for reality, religious symbolism had to be portrayed. Illarion Prianishnikov’s A Religious Procession of 1893, with its crowd of devotees straggling up from the banks of a great river having crossed from a church on the far bank, reminds us that the Christians originally baptised people in the river. Here it is as if the penitents have been through a purifying baptism before straining up the hill with their icons in a lengthy profession of faith.

It was not only the Volga, the ‘Mother of Rivers’ as Russians like to call it, which represented a potent symbol for Russian painting. It was all great rivers with their ambiguous connotations of continuity inextricably linked with simultaneous and inexorable change. On the other hand, rivers could simply be the setting for a genre subject such as Abram Arkhipov’s earlier Down the Oka, painted in 1889.

Surikov may well have re-used the arrangement of Arkhipov’s picture for his Stepan Razin. This, however, is a straightforward genre painting in which a group of peasants in a boat are about to reach the shore. Here the river has no particular quality apart from reflecting the pale golden haze and the subject is a nicely observed and painted slice of life.

Storms break regularly on the broad Volga. Ilya Repin had captured one twenty years before Dubovskoy in 1870 – and three years before his great Barge Haulers. Here the perilous view is from the stern of a low freeboard barge. The deck is swept by dirty seas as five men struggle with the great tiller and other crewmen shout advice from a forward hatch cover; all are about to be engulfed by a boiling white-topped sea.

Rivers turn out to be ideal for the artist to set mood. In the late 1880s the influential landscape Itinerant, Isaak Levitan, then in his twenties, made a visit to the Volga and painted it in all the states he could possibly observe. Evening on the Volga (1888) is an almost monochromatic study, the only colour a pink sunlit tinge to the top of a long grey cloudbank. Below, the waters of the river reflect the colour of the sky framed horizontally by the black of the foreground shore. Beyond a long silver wake is the distant black shore. Here is the moment before the remnants of the light quickly fade into black. It is a moment for grave reflectiveness, touching in its quiet dignity.

It is curiously more evocative than a painting of a similar scene by Arkhip Kuindzhi, Moonlight on the Dnieper of 1880. Here the structure of the composition is almost a mirror image of Levitan’s. The moon, set in a fortuitous break in the streaky cloud, casts an unearthly light on the glassy surface of the river visible between a dark foreground beach and the far shore, which merges into the black of the lower sky. Here is Kuindzhi’s striking colouring, depth, and mystery but the moment of transition is missing. Repin’s much more intimate Moonlight Night, Zdravnevo of 1896 has a woman in a white coat contemplating a moonlit river. The quiescent attitude of a dog lying at her feet suggests that she has been standing there for some time. What are her thoughts? Does she dream of release in the black river depths? Why is she standing there and what will she do next?

This is the river of dreams, still and yet driving on to its far distant destination in the sea. Daylight river studies by Levitan include Barges on the Volga of 1889 and On the Volga of 1888, in which the far distant bank is mirrored in the morning light, boats lie in the mud in the foreground, and an extraordinary light suffuses the sky, reflecting in the river in the middle ground. Fresh Wind: The Volga of 1895 has two barges being towed by a small steamer, the great river now a faintly choppy red reflecting the raw red banks and a mysterious red haze high in the sky.

Storm on the Sea at Night, 1849. Oil on canvas, 89 x 106 cm. The State Museum “Pavlovsk”, St Petersburg.

The Bay of Naples at Moonlight, 1850. Oil on canvas, 122 x 191 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

In 1887 Levitan wrote from the Volga to his friend Chekhov: “What can be more tragic than to feel the infinite beauty of one’s everyday surroundings, be fully aware of their innermost secrets, see God in everything and to realise that you simply cannot fully express these powerful emotions.”

Levitan’s definitive water painting is his Above Eternal Peace of 1894. He wrote of it, “It has the whole of me in it, all my psyche, all my content”. Under a sky of mixed clouds, the far distant plain stretches, with a hint of a lake here, a dense wood there. The main part of the picture is a great wide river in flood, “white as death”, as the artist described it. In the foreground on a promontory and surrounded by a small copse and a derelict graveyard is a traditional rural church with a tiny onion dome on the roof ridge.

Beyond in the flood a triangular piece of high ground has turned into an island. There is nothing else. This work of inner psychology represents one rare occasion when Levitan offers a less than golden account of the nature which he so loved.

A number of Levitan’s Volga studies incorporate boats propelled by the newly introduced steam power and even Aivazovsky, most of his life necessarily devoted to sail and the sea, produced a study of steam paddle boats on the Volga, The Volga near the Zhiguli Hills. Here is old and new side by side: a paddle steamer bravely occupies the middle-ground of the left half of the picture. On the far right shore a burlaki group hauls a train of barges in the time-honoured fashion, half obscured by a smart passenger steamer bustling up river. In the immediate foreground is a great raft of logs with a temporary hut on top and a group of itinerant woodsmen entertaining themselves until it is time to turn the raft into fodder for the downstream mills.

This is a painting of great optimism, suffused with a golden glow which is reflected in the water of the great river as a small flock of birds skim low in search of a last catch before roosting on one of the distant shores. This is also a painting about Russia in a state of change.

Landscape painting can be expressive of many things but it is not entirely surprising that Russian landscape should have running through it a strong theme of transition. In Arkhip Kuindzhi’s After the Rain of 1879, the low sun illuminates an emerald meadow and a low rise, on top of which are the reflecting walls of a group of farm buildings. The turbulent black sky retreats – but the stream in the foreground is in shadow, presaging another mighty downpour. In Isaak Levitan’s painting of the same name of ten years later, the water is still dappled with the remnants of a shower, a small paddle steamer, unaffected, bustles across the river, the old-fashioned barges of the middle ground swing at their moorings, while the puddled rainwater starts to form a little stream over the low foreground river bank.

And in Mikhail Larionov’s Rosebushes after a Rain Shower of 1904 the impressionistic brush strokes, long and vertical in form, serve as a reminder of the shower that has just passed across the pond in the far middle ground. Here is a moment of stillness captured, and overlaid by a visual memory of the showers insistent sharpness.

More dramatic than the moment when the noise of rain has receded and before the birds once more begin to sing is that moment of transition between calm and storm. Nikolai Dubovskoy’s The Calm before the Storm of 1890 has a great grey-bottomed bank of white cloud hanging above a lake, the far shore serving as a device to indicate the darkness beneath the cloud and, through the scale of the details, its relatively great distance from the viewer. The water reflects the lighter, almost sunlit zone of cloud. The tension is palpable. We know in real life that a thunderstorm is to do with wind currents, water vapour, and wild electricity, but in front of the picture we are almost waiting for the sky, or more accurately the heavy cloud bank, to fall with a thud on the face of the water. Dubovskoy wrote about the painting in terms of “that captivating feeling which has many times possessed me at the moment of calm before a major storm or in the interval between two thunderstorms, when it can be hard to breathe, when you sense how insignificant you are in the face of the approaching elements”.

For Isaak Levitan and many landscape painters the great mode of expressing the changing seasons of Russian Nature was the transition from snow to flood. His snowscape of 1885 is titled simply March. The thaw is about to begin. A bright late winter sun shines from over the viewers left shoulder. A temporarily untended horse with a sled waits patiently by the porch of a house, the incipient thaw indicated by the melting snow on its small roof and the mud of the road, re-emerging from the covering snow in the foreground. The bare branches of the trees have lost their snow and new growth has just started. So, too, in one of the earliest of the new Russian landscapes, Alexei Savrasov’s The Rooks Have Returned of 1871, the presence of the birds in the tiny, very early growth on the tall branches, and the meltwaters beginning to form a concerted mass of water among the fields of snow all herald the return of spring.

This theme of transition, the change of state from snow and ice to running water that takes place in early spring, fascinated many of the Itinerants. Quite apart from their own painterly agendas, they were themselves in a state of transition, moving from one way of painting to another, from one set of subjects to a new set – and of underlying, structural changes in society. Feodor Vasilyev’s 1871 The Thaw has a mother and child still warmly wrapped up and standing in the slush of an emerging old roadway defined by wheel tracks. In the centre of the picture a pond – still surrounded by snowy ground – has overflowed its bank and the cold meltwater leaks out into the foreground. In this painting of the same date it is difficult not to read the same allegorical message.

For later painters, such as Igor Grabar in February Sky of 1904, the transition is more subtle. It is difficult to distinguish the bark on the trunks and branches from the snow in this wonderful study in browns and blues of birch trees and their intricate array of branches in a snowfield backed by glimpses of a blue winter sky. Here, on the cusp of spring, the topmost leaves have started to appear and it is their colour, scarcely distinguishable from the light browns and whites of the branches, that gives the viewer the hint of things to come.

Ilya Ostroukhov’s wonderfully simple Early Spring of 1891 is a snapshot of those few days when the snow has begun to retreat from the bases of the trees, the water of the stream is beginning to eat away the edges of the snow, and in the back of the viewers mind is the thought that the level of the water indicates the beginning of a little flood. In Vitold Byalynitsky-Birulya’s The Emerald of Spring of 1915, the new pale green growth coexists with the slush of melting snow. In Stanislav Zhukovsky’s Spring Water of 1898 the process had gone a little further. Painted from an opposite bank, the shore in the middle-ground – now thinly covered with melting snow – is being overtaken by dark meltwater; three trees already have their bases under water. A tiny new stream also makes its contribution.

At the end of the transformation, the thaw becomes a flood – the theme of Levitan’s wonderful Spring Flood of 1897. Here the birch saplings stand forlornly in the water, their reflections adding to the sense of coldness despite the azure cloud-flecked sky above. A primitive boat nudges a temporary beach. In a week the waters will have subsided, the flooded farm buildings in the distance will return to use, and spring will be in full swing. The earth has awakened, and nature has emerged from her long hibernation.

The Snow

As the French discovered to their cost in 1812, for months on end each year much of Russia’s water turns to snow and ice and, when it is not blinding travellers and peasants, it lies thickly over the plains and mountains, rivers, and seas. It is so much a part of a Russian’s existence that when artists started painting it in the second half of the 19th century, people were surprised that they should do so.

The first of the Russian cold winter landscapes were actually painted as late as the mid-1860s and then by the social propagandist Vasily Perov, notably with The Last Farewell, The Troika, and The Last Tavern at the City Gates. All three paintings have snowscape settings, one of a young mourning family on a sled taking a coffin to the cemetery, and one of three children pulling an icicle-draped water barrel while the harsh wind blows streamers of snow from the eaves. The third painting is of two empty horse-drawn sleds waiting outside the candle-lit windows of a tavern, the city gates like stalagmites against the evening sky, the absent drivers destination somewhere in the icy wastes beyond.

A contemporary wrote of Perov’s work: “The landscape motifs – roads as endless as peoples patience, gloomy people, monotonous fogs, a severe winter with snow storms and blizzards, a bleak autumn with depressing rains and winds cold as the crying of death – become in his pictures as in folklore and the works of Dostoyevsky, Levitov, and Dickens, the bearers of tragic feeling personified as human misfortunes and burdens.” The Parisian critics of these and other paintings which Perov exhibited there in 1867 argued that at last here were identifiably Russian paintings.

Ships at Anchor in the Harbour at Sevastopol, 1852. Oil on canvas, 120.5 x 188 cm. Private collection.

In Perov’s socially aware work of this period the bitterly cold snow settings underline the sadness of the paintings narratives, as they do in lllarion Prianishnikov’s Returning Empty from the Market of 1872. A trail of horse-drawn sleds leads off along an ill-marked track through the broad plain of snow towards some wretched settlement beyond the horizon. A hunched figure on the rearmost sled seems to glower out at the viewer. And in Victor Vasnetsov’s Moving House of 1876, a middle-aged couple wrapped up and carrying a meagre bundle of their household goods trudge through the snow past the skeleton of a half-buried boat. Beyond the snowbound river, the dark ill-defined walls of a city conceal all but the tower of a church and a few tall chimneys.

Other Russian painters soon took up the theme of snow. In the Realist painter Viacheslav Schwartz’s The Tsarinas Spring Pilgrimage in the Reign of Alexei Mikhailovitch of 1868, a gilded sled makes its way out of a dark village at the head of a procession. The curving road leading into the picture plane is slushy, because the snow is about to thaw from the surrounding white fields. Schwartz was a painter of historical subjects who attempted to break the mould. He painted historical events as if they were genre paintings – that is, without the visual hierarchies of historical painting. The flat, all-enveloping, undifferentiating snow provides an important visual support to this. It is of course not difficult to read Spring Pilgrimage fundamentally as a landscape painting with an enigmatic though doubtless historically factual subject.

Schwartz’s position was not uninfluential and there followed from the brush of the Itinerant Vasily Surikov some of the great historical snow paintings, for snow is a wonderful setting for historical painting, representing as it does the rawest essence of barbaric Old Russia. His 1887 The Boyarina Morozova has the chained zealot, heroine of the losing side in the great religious schism of the mid-17th century, being dragged through the cold, snowbound streets of Moscow on a sled. Despite the thick snow which lies on the ground and on the roofs of the surrounding houses, she remains defiant, holding her hand in the newly banned two fingered sign of the cross. For students of composition the grey-white of the snow provides a semi-neutral background for the bright colours of the clothes of the people in the crowd, some jeering, some adoring, some angry. And white is the same colour as the boyarina’s cold hands and terrible face.

Surikov’s great snow painting Suvorov Crossing the Alps of 1899 depicts a real event in the war against Napoleon. Following a treacherous withdrawal by the Austrians, Russian general Alexander Suvorov stormed the St Gothard Pass and came down unexpectedly behind a French army and defeated it.

Travellers along the Caucasus Military High Road, 1855. Oil on canvas, 58.5 x 83.2 cm. Private collection.

The painting depicts a passage from that heroic march through the mountains. Urged on by Suvorov mounted on a horse, soldiers start sliding down a near sheer snowface, grinning devotedly at their general just before they take what, for all they know, could be their last fateful plunge. Perched perilously on the left of the painting are craggy white rocks and the hint of a mountain torrent. Lateral wisps of fog shroud the almost bare rocks of the crags above and lead the viewer’s eye beyond to the distant looming snow-clad slopes of the mountain beyond.

His The Taking of a Snow Fortress was painted at the urgings of his brother following Surikov’s profound depression at the death of his wife in 1888. It is perhaps historical only in the sense that it was a real, though disappearing, Cossack village custom, which Surikov had seen as a child in his village.

The locals would build a snow castle – more a fort surrounding a snow table heaped with snow food and snow utensils. It was the task of one team on horseback to attempt to take the fortress while another on foot banged tins and whistled and attempted to scare the horses. It was a great opportunity to get drunk, fight, and have fun. This is an immensely cheerful picture in which the last wall of the fort is breached and the rider topples a duck-like snow image from the top of a pile of snow and ice blocks.

In an experimental phase of history painting, mostly for the book Royal Hunting, the younger Valentin Serov revelled in the use of snow as a setting for genre paintings of Peter the Great and his successors hunting in the fields with their horses and dogs. Serov had already used snow as a setting for earlier paintings, such as the 1898 gouache In Winter and the 1910 study Rinsing Clothes, in which two peasant women kneeling in the snow by a tiny stream attempt to wash clothes while a bedraggled pony munches straw thrown on the ground to keep it and its sled close to the women.

Lago Maggiore at Night, 1855. Oil on canvas, 97 x 147.5 cm. Latvijas Nacionālais mākslas muzejs, Riga.

Ivan Shishkin, the most prolific of Russian forest landscape painters, was, curiously, not especially drawn to snowscapes, although his Winter of 1890 is an uncannily realistic, almost monochromatic study in which the silence of the snow-insulated forest is almost audible. As in an old sepia photograph, time stands still. In the same year Shishkin made studies in snow and another significant snow painting is based on a line in Mikhail Lermontov’s poem The Pine Tree.

In A Pine there stands in the northern wilds... the tree depicted in the northern wilds is a neat, heavily snow-laden conifer standing improbably on the edge of an icy winter cliff bathed in what seems to be moonlight. Shishkin is clearly experimenting with light, for the main body of the pine is in shadow and the snowy peak on which it stands bathed in the unearthly light.

It remained for Igor Grabar at the beginning of the 20th century to deploy snow as a subject for his almost Pointillist studies, September Snow of 1903 and February Sky of 1904. The former supports the proposition that winter starts early in Russia by showing a peasant woman carrying water up a path to houses at the top of the picture. This painting and February Sky represent the end of the serious Realist landscape movement – and in the latter painting, with its flat, clearly decorative intricacy, points in one of the many directions Russian painting was to take in the early decades of the new century.

In one zone of Russia, the Arctic, the winter never really ends. Aizavovsky’s wonderful Icebergs of 1870 sums up the most extreme form of frozen water. A three-masted ship, its sails all furled and with most of the crew on the foredeck, makes its way gingerly through the ice floes. In the foreground icicles hang from a small headland, flat floes creaking together in the neighbouring sea. And in the middle ground, towering over the ship, is the gigantic tip of a great iceberg, its battered and fractured surface illuminated by an almost unearthly light which somehow eludes the ship below. Here is a great piece of scenery painting but also surely an allegory of the profound uncertainty which always surrounds the behaviour of the great waters.

A Large Sailing Ship off the Beach near Capri, 1858. Oil on canvas (oval), 33.3 x 38.6 cm. Private collection.